Monthly Editorial: June 2022

Abstract:

The dominant political philosophy of education has designed single narratives of history in order to construct a collective memory that could foster social cohesion. In this issue, however, we uncover testimonials from teachers, students and other education stakeholders who engage in historical discourse that suggest how in education settings certain critical discourses about the past can create pathways for various forms of justice. The discussions prompt further inquiry into the extent to which educationists have a moral responsibility to facilitate self-transformations and engage with controversial or conflicting narratives.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2022-20120

Languages: English

In the last few years, historians have furthered arguments favouring the moral responsibility of directing historical discourse toward addressing social justice.[1] Memory studies have also described a sense of moral responsibility in ensuring that the writing, reading and studying of history fosters [social] justice.[2] There are those, of course, who have warned against enforcing justice through history.[3] We, therefore, focus on the philosophical and practical dilemmas of whether or not to facilitate critical historical discourse for learners in educational settings to directly address social injustices.

A Moral Responsibility?

Coming from conflict-affected areas, we – the co-editors of this issue – live within a social context that is still plagued by a history of injustices and, as a result, struggles with how to approach talking and learning about history. We grew up in countries divided by ‘Green Lines’ – namely, Cyprus and Lebanon. In both countries, discourses regarding history and justice have fierce and conflicting narratives. On the one hand, certain public actors have been adamant that violent pasts should be critically examined, crimes and blame should be acknowledged and that, thereafter, culprits should be brought to the fore and punished. On the other hand, others argue that we should move away from past divisions and blame because they will only reopen wounds and, instead, focus more on social reconstruction by examining historical accomplishments. We were involved professionally in these debates in the places we grew up. We taught students and teachers history and citizenship and the purposes around them. These experiences and the debates around their functions prompted us to reflect and open discussions on the relationships between history and justice.

We, therefore, question whether historians, thinkers and educators have a moral responsibility to either address, curate or avoid critically examining narratives that help learners answer questions about violent histories. Does, then, justice have a place in history? This Public History Weekly issue will address this question by drawing on testimonials of practice and critical reflection from history educators and professionals in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Justice in/and History

Discussing the relationship between history and justice is challenging because, to start with, there are different ideas about what the two concepts, history and justice, are. The idea of history raises a number of meanings and a wide range of connotations. As Jordanova pointed out, “since one of the main meanings of history is simply ‘the past’, almost any association with past times to be transferred to ‘history’ as a discipline”.[4] There is also the question of history’s capacity. Should we accept, for example, that “the past is a foreign country”[5] or that history deals with what is no longer visible and understandable?

The idea of justice also brings forth different understandings and functions of fairness and equity. As Kokkinos very thoroughly explains in the first article of this issue, there are different definitions of justice. For instance, justice through retribution (punishment) focuses on the perpetrator; restorative/reparative action addresses financial and moral responsibilities and involves the symbolic redress of defamation; and, transitional justice focuses on victims by acknowledging the human rights violations committed against them, engaging perpetrators in reform and accountability to transform mechanisms of violence and prevent future forms and incidents of violence or neglect. There are, of course, other categorisations and other ways of theorising justice. Nancy Fraser, for example, talks of social justice and the fairness and equity of participation, compelling us to push the boundaries of equality both in theory and in practice and to reimagine the promotion of rights beyond national borders.[6]

The question on the relationship between history and justice is not, however, convoluted simply because of the ambiguity surrounding the two concepts. Their relationship can be viewed differently depending on which scale the discussion takes place; such as international agencies and organizations versus local organizations and government agencies. Different cultural dimensions such as religion will also affect how we see their relationship.[7] Then, there are questions which, albeit philosophical, are, in fact, fundamental. Can we have differentiated ethics, or is there a universal law of ethics? Furthermore, if there is a universal law of ethics, are we obliged to be ethical? Margalit’s stance, for instance, is that we are not obliged to be ethical, only moral:

There is no obligation, in my view, to be engaged in ethical relations. It remains an option to lead a polite solitary life with no engagements and no commitments of the sort involved in ethical life. The ought of morality, on the other hand, is different from the ought in ethics. Being moral is a required good; being ethical is, in principle, an optional good. The stress is on “in principle.” There is no easy exit from ethical engagements, many of which are forced on us in much the same way that family relations are.[8]

Acknowledging the existence of different interpretations, stances and positionalities on justice in/and history, we wanted to explore how the intersection of history and justice creates either a conflicting or complementary relation or dynamic in the education sphere. We wanted to examine the relationship between history and justice within educational settings by giving the floor to history professionals that are involved in the dissemination of historical discourses through teaching and/or public history dissemination.

Dialogues from the Eastern Mediterranean

This issue will examine different perspectives on how public actors, namely historians, thinkers and educators understand the role of history when it comes to attributing responsibility and blame. Explicitly, it will discuss different and even conflicting stances in relation to assigning, avoiding or acknowledging justice in relation to victims and perpetrators. The relationship between history and justice concerns the studies of social scientists from different disciplines, such as anthropology, psychology, philosophy, history and political science. Each of these disciplines also uses different methodologies and approaches in their knowledge production. It is for this reason that we have invited scholars from different disciplines and contexts to contribute to this issue.

The authors in this issue outline theories of justice (e.g. the recognition of past damage – physical, emotional and material – and the ascription of blame or responsibility for violent events) and examine the different and even conflicting positions of either assigning, avoiding or acknowledging victims and perpetrators in historical discourse. They also present contextualized theorisations of justice and address the need for justice drawing on specific country case-studies. The implications, dangers and moral dilemmas of justice are also discussed. The authors problematise the obligation to be engaged in justice, with some arguing that history and justice are fully connected and others challenging this stance.

Undoubtedly, as comes out from the five articles on this issue, history and justice inherently share a complex relationship. On the one hand, it could be argued that the relationship between history and justice should not be taken for granted. The argument here is that neither is justice obliged to engage with history, nor there is an obligation for history – including history education – to engage with justice. As Meyer argues, justice has a responsibility to future, not past generations.[9] Furthermore, it can be argued that history has the power to empower individuals and, thereafter, communities when it steers away from serving political goals and social engineering – which is bound to happen, by default, as “history” as a social practice “is closely connected to almost all cultural functions and forms”[10]; it is only then, that history can be moral and fair.

On the other hand, it can also be argued that history cannot turn a blind eye to injustices. Hence, teaching critical and deliberative pedagogies in historical discourse in education is a valuable opportunity to foster transitional and social justice. The intentional seeking out of narratives from minority and under-represented groups is a moral responsibility of teachers, which may only happen once they engage in critical, introspective reflections of their political positions and ability to emotionally distance themselves from collective memories.

Our stance is that history does have an ethical obligation to be moral. What this means for history’s relation to justice is a question that needs to be addressed through critical and multiperspective dialogues, as we set out to do in this issue.

The Articles in This Issue

The first article by Georgios Kokkinos in this month’s “History and Justice” issue, in essence, serves as an introduction. This is because, by discussing “Historical justice and historical thinking and consciousness”, Kokkinos gives both an overview of historical justice and historical thinking and consciousness, and of their relationship. In his article, he illustrates the three forms posed by social and political theory – that is, retributive, reparative/restorative and transitional justice – which he illustrates with examples. He highlights that the distinguishing feature of transitional justice is that it is constituted with the purpose of becoming part of a complete framework of socio-political processes aiming at historical self-knowledge, moral cleansing and potential reconciliation; he then proceeds to point out that in the historical consciousness, too, there is always an ethical background. Kokkinos concludes that part of the moral dimensions of history is the historicization of public memory, by referring to Roger Simon and his concept of critical pedagogical memory, and pointing to Belgium’s example of “memory education”.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2022-20122

In the second article of the issue, “History in Court: The punishment of the Asia Minor Catastrophe (1922) culprits”, Christina Koulouri problematises the urge for “historical justice”, by drawing on the not widely known 2008 request for the vindication of “The Six” (that is, the six Greek military offices convicted in relation to the 1922 Asia Minor “Catastrophe”) substantiated by the argument that new evidence showed a miscarriage of justice. Explicitly, in January 2008, Michalis Protopapadakis, grandson of Petros Protopapadakis, a former prime minister who had been convicted and executed in 1922 on charges of high treason, submitted to the Supreme Court a request for a retrial of the Six. Two years later, the Criminal Division of the Supreme Court met to review the evidence that led to the execution of the Six in November 1922, 87 years ago. Drawing on this unprecedented decision, Koulouri raises a number of issues that are worth discussing: Is it a legal, political or historical issue? Is it possible for court clerks to (rewrite) history? How do they check the validity of information/evidence? Are they aware of the vast literature on the Asia Minor Catastrophe, the various interpretations, but also the commonalities that exist in Greek historiography regarding the Trial of the Six? In a pointed manner, Koulouri argues that actions such as the retrial of “The Six” will certainly not add anything to our historical knowledge while the decision has no legal but clearly political content.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2022-20123

Wadiaa Khoury reflects on the context, struggles and breakthroughs of one teacher trying to engage learners in open and critical historical discourse in the classroom. In a context where history is highly contentious and history education reform has consistently failed since 1970, historical narratives in the classrooms are limited to what dominant groups dictate, which align with the respective community’s collective memory. As a reflection of Lebanon’s fragmented society, school teachers, to a great extent, are strongly committed to their political backgrounds and collective memories that have shaped the hidden curriculum in the classroom and how children engage in historical discourse. Khoury illustrates how teachers’ self-transformation of approaches to politics and history is an indispensable pathway for justice allowing learners to also adopt an open mind when reading conflicting narratives of how the civil war of 1975-1990 began.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2022-20124

In the fourth article of this issue Michalinos Zembylas deals with “Morality, ‘Difficult’ History, and Teacher Education”. He puts forward that teachers’ stance on the Cyprus conflict is a matter of morality, by drawing on a series of workshops he organised for a small group of Greek-Cypriot teachers addressing, among other, issues on the prospects of peace education in Cyprus. Zembylas refers to the teacher workshops to discuss what impact an adamant moral stance on “victims” and “perpetrators” might have on the prospects of peace education, when individuals – in this case, teachers – are too emotionally involved and have strong moral convictions that justice and truth are on their side. Zembylas suggests that teachers who resist negotiating their deeply felt moral stance and the possibility of moving beyond their emotional experiences of trauma need to have opportunities to engage with “difficult knowledge”.[11] Concluding, Zembylas indicates that teachers need opportunities that create openings for “moral repair”[12], namely, ways that move from the situation of loss and damage to a situation where some degree of restoration of moral relations may begin.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2022-20129

Kefah Barham from Palestine and Bassel Akar from Lebanon capture a debate between two groups of youth in Palestine on how historical discourse should serve dimensions of transitional and social justice. One group of youth argued for the studies of comparative history to learn lessons from the fall of the apartheid in South Africa and how Vietnamese people found safety from the US army. Another group of youth felt that learning about the Islamic Golden Age would help them find inspiration and approaches to autonomy and sovereignty.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2022-20125

_____________________

Further Reading

- Scott, Joan. “History-writing as critique.” In Manifestos for history, edited by Sue Morgan, Keith Jenkins and Alun Munslow, 19-38. London: Routledge, 2007.

- Hannoum, Abdelmajid. “Paul Ricoeur On Memory.” Theory, Culture & Society 22 (6) 2005: 123-137. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276405059418.

- Rüsen, Jörn. “How to Overcome Ethnocentrism: Approaches to a Culture of Recognition by History in the Twenty-First Century.” History and Theory 43 (4) 2004: 118-129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2303.2004.00301.x.

Web Resources

- The Historical Dialogues, Justice and Memory Network. https://historicaldialogues.org/scholarship/journals/ (last accessed 1 June 2022).

- Institute for the Study of Human Rights. https://humanrightscolumbia.org/ (last accessed 1 June 2022).

_____________________

[1] Joyce Hope Scott, “Reparations, Restitution, Transitional Justice: The International Network of Scholars and Activists for Afrikan Reparations (INOSAAR),” Journal of World-Systems Research 26, no. 2 (2010): 168-174. https://doi.org/10.5195/JWSR.2020.1010.

[2] Avishai Margalit, The Ethics of Memory (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004).

[3] David, Lea. The Past Can’t Heal Us: The Dangers of Mandating Memory in the Name of Human Rights. Cambridge University Press, 2020.

[4] Ludmilla Jordanova, History in Practice (London: Hodder Arnold Publications, 2006), 13.

[5] David Lowenthal, The Past is a Foreign Country (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

[6] Nancy Fraser, “Social justice in the age of identity politics: Redistribution, recognition and participation,” in Culture and economy after the cultural turn, ed. Larry Ray and Andrew Sayer, (London: Sage, 1999).

[7] Max Pensky, “Solidarity with the Past and the Work of Translation: Reflections on Memory Politics and the Postsecular,” in Habermas and Religion, ed. C. Calhoun, E. Mendieta, & J. VanAntwerpen (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2013), 301-321.

[8] Avishai Margalit, The Ethics of Memory (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004), 105.

[9] Lukas Meyer, “Intergenerational Justice,” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N. Zalta (ed.). (Summer 2021 Edition). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2021/entries/justice-intergenerational/ (last accessed 1 June 2022).

[10] Maria Grever, Robbert-Jan Adriannsen, “Historical culture: A concept revisited,” in Palgrave Handbook of Research in Historical Culture and Education, ed. Mario Carretero, Stefan Berger and Maria Grever (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 73-90.

[11] Deborah P. Britzman, Lost Subjects, Contested Objects: Toward a Psychoanalytic Inquiry of Learning (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press 1998); Deborah P. Britzman, “If the Story Cannot End: Deferred Action, Ambivalence, and Difficult Knowledge,” in Between Hope and Despair: The Pedagogical Encounter of Historical Remembrance, ed. R.I. Simon, S. Rosenberg, and C. Eppert (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2000), 27-57.

[12] Margret Urban Walker, Moral Repair: Reconstructing Moral Relations after Wrongdoing (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

_____________________

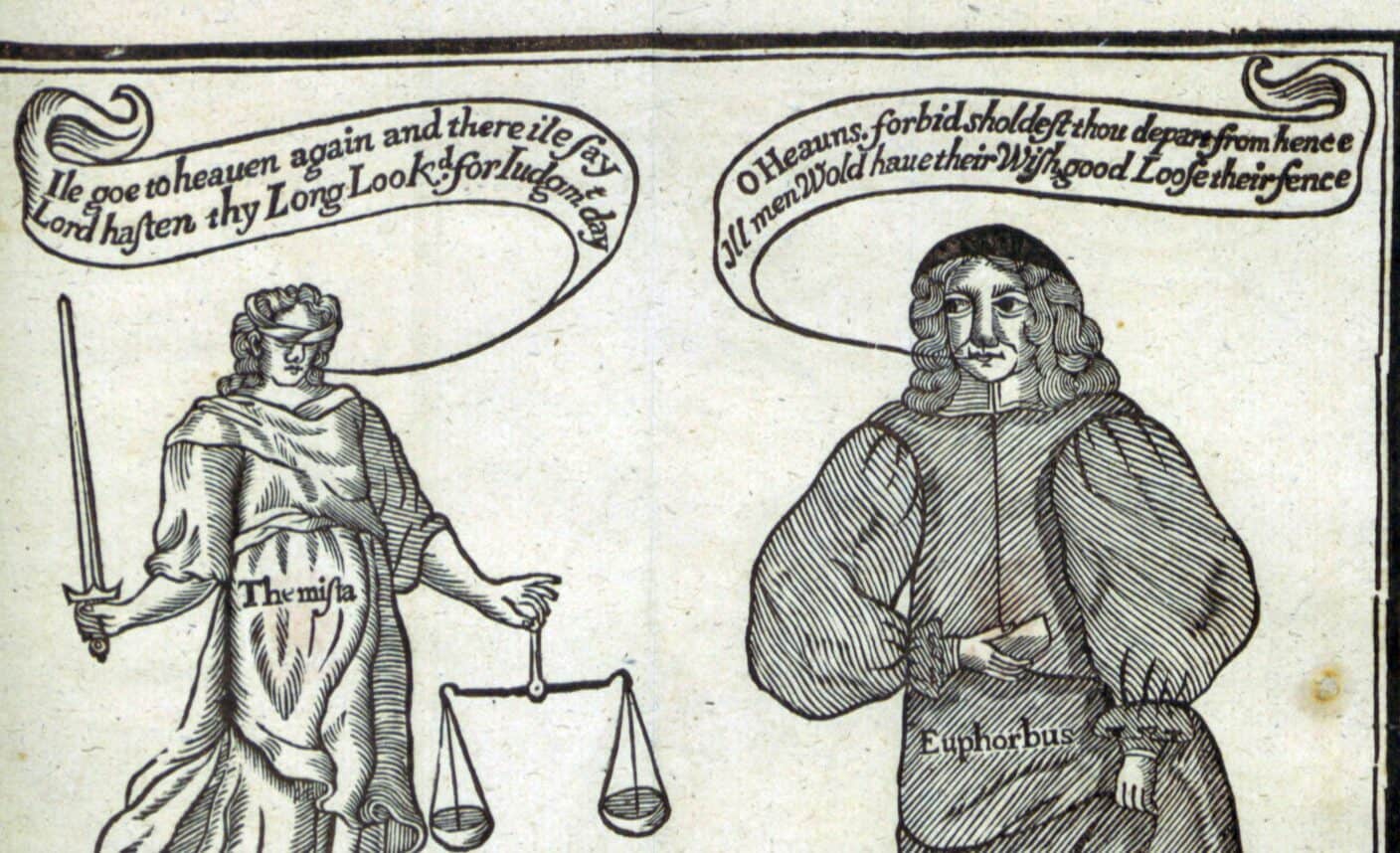

Image Credits

Themista and Eupherbus, in a familiar dialogue [in verse] … discovering, and passionately bemoning, … the Exorbitances of the World in the Administration of Justice … By Philopolites, 1683, London © Public Domain via flickr/British Library.

Recommended Citation

Georgiou, Maria K., Bassel Akar: History and Justice: Dialogues from the Eastern Mediterranean . In: Public History Weekly 10 (2022) 5, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2022-20120.

Editorial Responsibility

Copyright © 2022 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 10 (2022) 5

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2022-20120

Tags: Cyprus (Zypern), Greece (Griechenland), Historical Justice, History Education (historische Bildung), Lebanon, Mediterranean (Mittelmeerraum), Social Justice (Bürgerrechte)