Monthly Editorial: June 2023

Abstract: Is it possible to separate geography from history and what role do place names play in positioning the things they name politically? These are two of the many questions raised by the exploration of naming, histories and geographies that we address in Public History Weekly this month, through a series of articles that explore how the histories and identities of the nations located in an archipelago on the Atlantic coast of Europe present themselves and each other through their school history curricula.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21686

Languages: English

Naming has often been thought of as a kind of magic, as if in knowing something’s true name, one controls it.[1] Naming appropriates, it locates the thing named in a language and universe of meaning and doing so often excludes others and the differing meanings their namings might make. Namings can also have histories – much ink and much blood has been spilt over names. In this article we discuss the term “the British Isles”: is it simply a geographical term or does history complicate things?

The Power of a Name

Naming is central to history-making. ‘Whose story should a history tell?’ is a pivotal question in any act of historical narration and this is what makes any history a ‘history of X’ or ‘of Y’ or ‘of Z.’ Identifying the ‘whom’ to be narrated involves naming ‘it’. Narrative logic also shapes decisions about protagonist/s and antagonists and decisions about the properties attributed to subjects of narration.[2] ‘What kind of story is a history to be?’ is a vital consideration also, as White has argued,[3] and so is determining what entities we bring together and which entities we keep apart in our story-telling. Choices of which aspects of the past to foreground and which to background are also acts of narrative voicing and silencing.[4]

The ‘British’ Isles

“In this Ocean there happen to be two very large islands which are called Britannic, Albion and Ierna, bigger than any we have mentioned.”[5]

The politics of naming and tying together through story play a vital role in the case of a group of islands on the Atlantic coast of Europe, often referred to as ‘British’, in a practice that has some ancient precedents, as our quotation from Psuedo-Artistotle shows, but that is, as namings so often are, contested. For some, the British Isles is a purely geographical term, but for others, it is a loaded question of politics. While the term ‘British’ is not, in itself an explicit political term, it reflects a political situation in which four separate nations were combined under one sovereign ruler that began in Tudor times. The terminology most often used to express the geographical unity of these isles is actually subject to what Macdara Dwyer describes as the “political fragmentation, regional differences, and national sensitivities” that are contained within both the geographic and political space inhabited by the ‘four nations’ of the island group.[6]

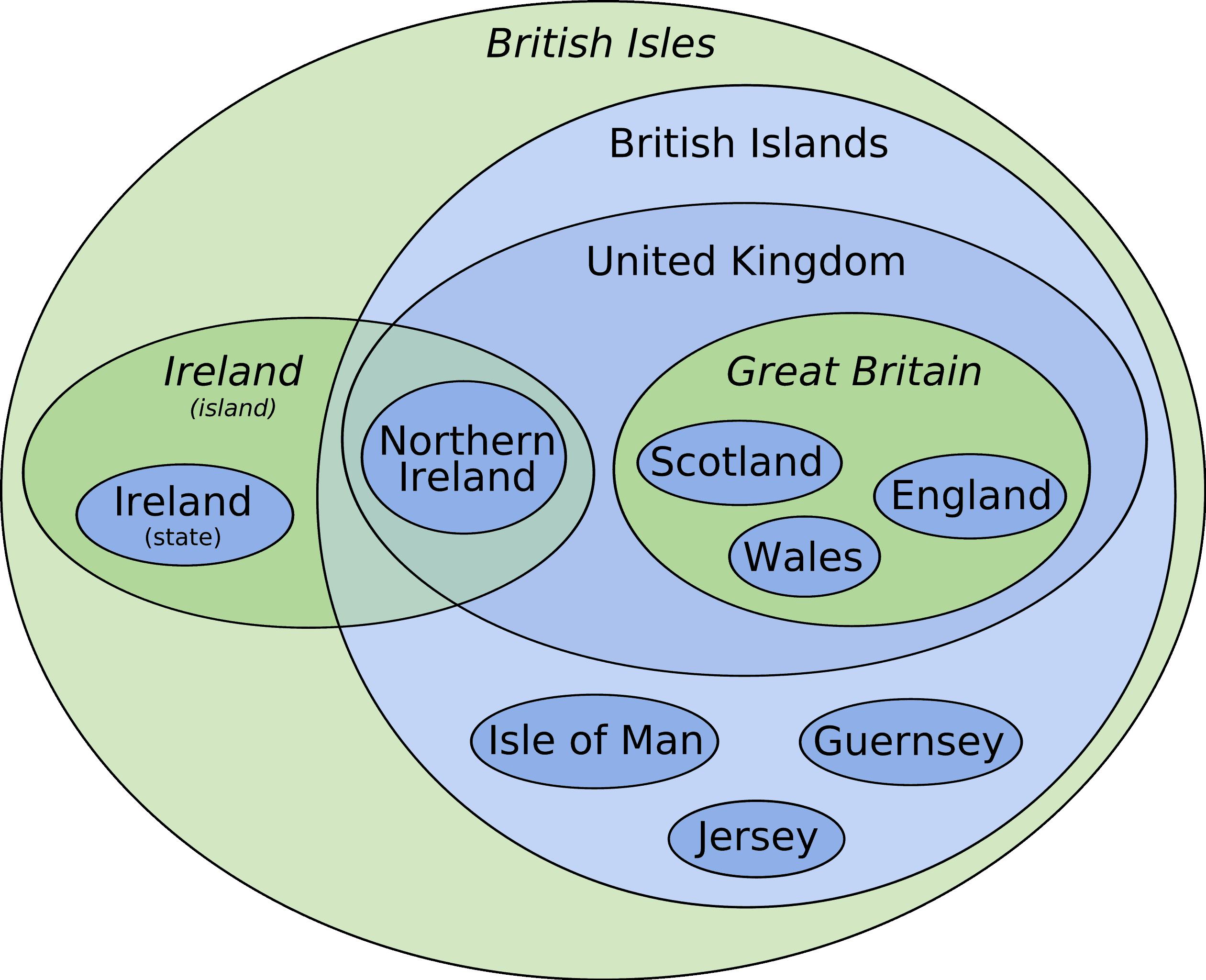

Fig. 1: Euler diagram of the British Isles, via Commons

Fig. 1: Euler diagram of the British Isles, via Commons

This fact has led some historians to strive to find more neutral terminology than ‘British’ – a term associated with the British Crown and the British State, political entities dating, in constitutional and legal terms at least, from the Act of Union of 1707 that united England, Wales and Scotland together into a ‘United Kingdom’, into which the island of Ireland was formally incorporated in 1801, and from which all but six counties broke free in 1922 with the founding of The Irish Free State.

Whilst speaking of names, for a number of reasons – politically, culturally and socially – there is also confusion about what exactly is meant by the names United Kingdom (UK) and Great Britain (GB) and indeed the correct term for Ireland. The United Kingdom refers to the political union of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, Great Britain being England, Scotland and Wales. The correct term for the whole island of Ireland is Ireland and the correct term for what is sometimes, erroneously, referred to as the Republic of Ireland is also Ireland (or Éire in the Irish language).

To illustrate the importance of naming, historian Mary E. Daly describes the guidelines on politically correct geographic terminology given to Irish delegates at an international geography textbook meeting in 1963 “‘British Isles’ and ‘United Kingdom’ were deemed objectionable; delegates should insist on ‘Ireland’ and ‘Great Britain’; ‘Republic of Ireland’ should be avoided.”[7] The use of the term “British Isles” was further clarified by the Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs, Dermot Ahern in September, 2005 “The British Isles is not an officially recognised term in any legal or inter-governmental sense. It is without any official status. The Government, including the Department of Foreign Affairs, does not use this term.”[8]

The eminent historians John Pocock and Norman Davies sought to address these problems of naming through alternative nomenclature, proposing as alternatives to ‘British’: ‘The Atlantic archipelago’ (Pocock) or, more simply, ‘The Isles’ (Davies).[9] A solution that turns to geography – as others such as Hugh Kearney have – to navigate the challenges that terms connoting polities can create.[10]

Geographies and Histories

The Euler diagram (Fig. 1) points to some of the affordances that a geographical focus (items shaded in green) gives in navigating the complexity of political-legal frameworks (items shaded in blue). As the model indicates, the British Isles consists, largely, of two islands – Great Britain (the largest) and Ireland. All of one island (Great Britain) and part of the other (Northern Ireland) currently form one political structure (the United Kingdom). The island of Ireland contains two legal entities – Ireland and Northern Ireland. Great Britain contains three – England, Scotland and Wales.

To tell the stories of the political entities in ‘The Isles’ is to face some quite formidable narrative challenges – political-legal entities have defined and delimited existence (Northern Ireland, for example, dates from 1922) and telling a story over any length of time presents the challenge of discontinuity: whose story can one tell, if the subject of narration keeps changing as new structures come into being and old structure cease to be?

A geographical framing, on the other hand, allows continuous stories to be told, since geographical elements are constants in history (if not in pre-history): continuous histories can be told of locales in which political entities arise and pass and in which histories are told and retold, and remembered and forgotten. We can see this approach at work in Davies’ book The Isles in which ‘The Isles’ become the site in which various formations come into being and pass away: the ‘Germano-Celtic Isles’ (410-800), ‘The Englished Isles’ (1326-1603) and the ‘Post-Imperial Isles’ (1900 onwards), to give three examples.[11]

Our Island Stories

The problem with this geographical approach, however, is that, since the age of nationalism at least, the chief sponsors of history infrastructure in universities and schools have been nation-states – entities who want their histories to be foregrounded and made ‘permanent’ in the minds of their citizens, even if the historical record shows that they are historically contingent.[12] This urge to identity and continuity presents some fascinating problems in comparative school history, revealed when we look at the various ways in which the political entities in the ‘Atlantic archipelago’ deal with – or evade – the histories of each other.

Just as there are five political entities in ‘The Isles’ currently – Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and England – there are five corresponding history curriculum creators. It must surely have raised many eyebrows, and even more questions, in four out of five of these authorities to find, in 2013, that the first aim of the new ‘National Curriculum’ promulgated that year by a Conservative-led coalition in Westminster was “to ensure that all pupils: know and understand the history of these islands as a coherent, chronological narrative, from the earliest times to the present day”[13] – a proposition that treats the history of islands (plural) as a single continuous story (“the history… a… narrative”), thus eliding the history of Ireland with the history of Great Britain and reducing geographical pluralism to narrative monism; and eliding the histories of the Scots, the Northern Irish, the Welsh and the English into one, and reducing national pluralism to narrative monism.

The latter was also, perhaps, implied in the title of the document – not ‘The English national curriculum’ but the ‘National curriculum in England;’ a phrase that implies, perhaps, that British history exists as a ‘national’ history and that the curriculum simply interprets it in England. A suggestion supported by the fact that the history section uses the words ‘England’ and ‘English’ six times and the words ‘Britain’ and ‘British’ thirty-five times.

This Month’s Contributions

Our contributions this month explore aspects of the ways in which histories in these islands are constructed and how the nations in these islands see each other, and – in four out of five cases – this is explored through past and present history curricula and textbooks.

Between 1845 and 1852, Ireland experienced one of the most devastating natural disasters of the 19th century. Known in the Irish language as An Gorta Mór, the Great Famine was a time marked by starvation, disease and emigration that signalled a turning point in both Irish history and Anglo-Irish relations that still resonates today. Caitríona Ní Cassaithe and Lindsay Janssen use the Irish Famine as a case study to explore the teaching of Irish history in Britain. They argue that while the inclusion of an Irish dimension in British history curricula is important in regard to mutual understanding across ‘these islands’, it also has a role to play in how the present is contemplated.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21666

In our second paper, Rhonwen Bruce-Roberts provides an overview of the limited presence of Welsh history in Welsh and English curricula, and the challenges in its teaching. In 1888, the Encyclopaedia Britannica infamously read, ‘For Wales, see England’ highlighting a lack of understanding of the cultural differences between England and Wales. As our author argues, this portrayal still exists in the context of teaching history.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21665

In our third paper, Joseph Smith and Arthur Chapman look at relationships between Scotland and England as these are addressed in the Scottish ‘Higher’ History curriculum and in the English pre-university ‘Advanced Level’ History curriculum – examinations that are roughly comparable in their function in serving pre-university national examinations. The authors compare how the two countries deal with the question of change in status relative to each other and to ‘Britain’ arising from the Act of Union (1707), and contrast what they call the English ‘continuity-state’ and what they call the Scottish ‘split-screen’ narrative strategies as tools for managing the challenges that arise for national narrative in a multi-national state.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21664

In our fourth paper, Jocelyn Létourneau and Raphaël Gani ask what words do English, Scottish and Welsh nationals most often use to inform or articulate their statements when asked to capture the essence of their nation’s historical experience in one or two sentences. The authors ask could it be that, in talking about their nation over time, they are (un)consciously drawing on a national vocabulary that carries with it the challenges, issues, attributes, salient features, and other idiosyncrasies of what Benedict Anderson called ‘imagined communities’ and Michael Billig associated with banal nationalism?

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21663

Our final theme paper by Colm Mac Gearailt explores the representation of the English in Irish history textbooks published between the 1920s and the end of the 1960s, and tests the widely held assumption that the English were represented uniformly in two-dimensional ways as villains and enemies of Ireland. The results of a systematic survey of textbooks allow conclusions to be drawn about both the extent to which textbook narratives tended to what might be called a typical nationalist framing (privileging struggle and framing opponents of the nation in simplistic binary terms), and the extent to which the English are or are not represented as enemy ‘others’.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21667

Our Speaker’s Corner paper by Alan McCully is a personal reflection on his experiences as a student, teacher and lecturer over thirty years of violent conflict in Northern Ireland, where a fragile peace process and the unaddressed issue of legacy combine with a society quickly evolving in diversity and social values to provide a dynamic if unstable environment in which to examine the difficult past. As the author argues, for educators that context is made more complex by communal division in the education system which is still over 90% segregated between those from unionist/Protestant and those from nationalist/Catholic backgrounds.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21809

_____________________

Further Reading

- Davies, Norman. The Isles. First Edition. London: Macmillan, 1999.

- Kearney, Hugh. The British Isles. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Reynolds, David. Island Stories: An Unconventional History of Britain. London: William Collins, 2020.

Web Resources

- The English Department for Education’s The National Curriculum in England: history programmes of Study: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-history-programmes-of-study/national-curriculum-in-england-history-programmes-of-study

- The Irish Primary History Curriculum and Teacher Guidelines: https://curriculumonline.ie/Primary/Curriculum-Areas/Social-Environmental-and-Scientific-Education/History/

- The Irish Junior Cycle Specifications for History: https://www.curriculumonline.ie/Junior-Cycle/Junior-Cycle-Subjects/History/

- The Northern Irish Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment’s History: Key Elements and Resources: https://ccea.org.uk/key-stage-3/curriculum/environment-society/history

- Education Scotland’s Curriculum For Excellence Social Studies curriculum: https://education.gov.scot/education-scotland/scottish-education-system/policy-for-scottish-education/policy-drivers/cfe-building-from-the-statement-appendix-incl-btc1-5/curriculum-areas/social-studies/.

- The Welsh Government’s Curriculum for Wales Humanities curriculum (children aged 3 to 16 years): https://hwb.gov.wales/curriculum-for-wales/humanities/

_____________________

[1] “The Shakespeare Code”, Doctor Who, April 7, 2007.

[2] Robert F. Berkhofer, Beyond the Great Story: History as Text and Discourse (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1995).

[3] Hayden White, Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975).

[4] Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2015).

[5] Hugh Kearney, The British Isles, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), epigraph (Aristotle,De Mundo c.iv).

[6] Dwyer, M. “The ‘British Isles’; A Brief History of a Term from A Four Nations Perspective” 14 March, 2016. https://fournationshistory.wordpress.com/2016/03/14/the-british-isles-a-brief-history-of-a-term-from-a-four-nations-perspective/#_edn3(last accessed 30 May 2023).

[7] Daly, M. (2007). The Irish Free State/Éire/Republic of Ireland/Ireland: “A Country by Any Other Name”? Journal of British Studies, 46(1), 72-90. doi:10.1086/508399 (p. 83).

[8] https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/question/2005-09-28/495/(last accessed 30 May 2023).

[9] John Pocock, The Discovery of Islands: Essays in British History (Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005); Norman Davies, The Isles, First Edition (London: Macmillan, 1999).

[10] Kearney, The British Isles.

[11] Davies, The Isles

[12] Stefan Berger and Christoph Conrad, The Past as History: National Identity and Historical Consciousness in Modern Europe (Houndmills: Palgrave MacMillan, 2015).

[13] Department for Education, “National Curriculum in England: History Programmes of Study,” GOV.UK, 2013, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-history-programmes-of-study/national-curriculum-in-england-history-programmes-of-study (last accessed 30 May 2023).

_____________________

Image Credits

Title image: Great Britain + Ireland – John Speed proof maps 1605-1610 via Flickr.

Fig. 1: Euler diagram of the British Isles, via Commons

Recommended Citation

Chapman, Arthur, Caitríona Ní Cassaithe: The ‘British’ Isles: Complex Histories or Simple Geographies?. In: Public History Weekly 11 (2023) 5, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21686.

Editorial Responsibility

Copyright © 2023 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 11 (2023) 5

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21686

Tags: Conflict of Memory, Curriculum (Lehrplan), Editorial, Great Britain (Grossbritannien), Ireland, National Identity (Nationalidentität)

To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

OPEN PEER REVIEW

Intriguing and important issues

Although this issue focuses on developments and issues in the component countries of what has been termed the Atlantic Archipelago, the questions posed are relevant to many other parts of the world, whether the differences in contingent groupings are federational, regional, cultural or economic.

The diagram pointing out the various nomenclature for England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales is extremely helpful, not least because many people within these countries are uncertain about the differences between them, not to mention ‘outsiders’. What is important is that history education helps people not just to be precise in using the terms involved, but to understand ‘what games are being played’ with the past by bringing to bear different geographical terms to issues of identity and belonging. These things matter (as noted, ‘much ink and blood has been shed’). It is also important because things change over time; in 1991, when the National Curriculum for history was first introduced to apply to schools in England, Scotland and Wales, it made some sense to talk of ‘developments in history teaching in the UK’, but since measures of educational devolution were introduced in the 1990s, this is no longer the case.

As the authors have pointed out, the National Curriculum requirement that ‘all pupils should know and understand the history of these islands as a coherent, chronological narrative, from the earliest times to the present day’ – as if there is just one simple, single story to be told, is unhelpful, unrealistic, and demonstrates a lack of understanding of the nature of the discipline of history.

The metaphor of a ‘split screen’ narrative is a useful one. Young people need to know and understand both how things are developing across the component countries of the UK (for instance, in relation to the impact of Brexit, or social and cultural developments), and about the changing relationships and tensions between the four countries. They need to be able to see the wood and the trees.

This issue of PHW raises intriguing and important issues for public history. The synopses provided in the introductory paper made me keen to read the contributions to the issue.