Abstract: In India, heritage sites and museums are key places of public consumption of history. Heritage tourism has flourished in the last decades. Here, we probe into how heritage as a field has evolved in India, who are the actors, how interpretation and presentation of heritage and historical narrative are devised and exploited in tourism. Packaged authenticity, commercialisation, public-private partnerships, sustainable and responsible change, what lies ahead for heritage tourism practice? We explore.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21498

Languages: English

In India, cultural tourism has a big potential for development given the diversity of sites and experiences the country has to offer. Conscious publicity campaigns like ‘Incredible India’ are aimed at highlighting the richness of Indian traditions. Indian tourism, primarily reliant on domestic numbers, is also making efforts through infrastructure projects and publicity to attract inflows from abroad. In this, the role of heritage becomes very important. However, how heritage and historical narrative are instrumentalised in this context needs to be reflected on.

Presenting History in Public: Who is in Charge?

The roots of heritage protection and its conservation in India can essentially be traced back to the colonial period. The establishment of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) in 1861 led to the creation of a framework and infrastructure for managing historical sites and also defined a mandate for their preservation and presentation, which continues to guide heritage management in India even today.[1] Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) established in 1984 was created with the aim of preserving and promoting the unprotected heritage which fell beyond the purview of the state bodies.[2] INTACH has mobilised the heritage movement in the country to a great extent. Through activist efforts, many heritage sites were saved from destruction and damages.

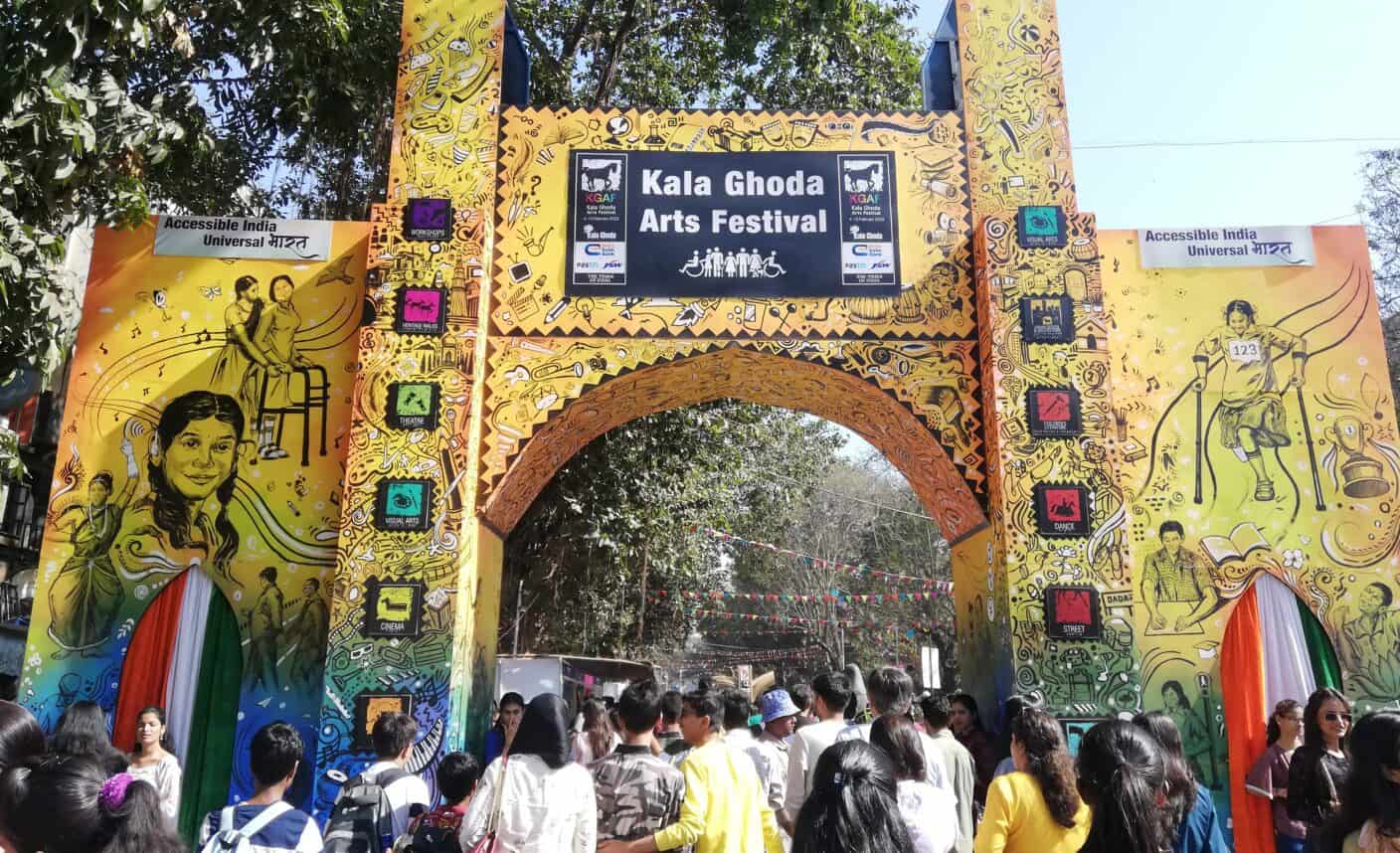

In the post-industrial period, heritage became a big contributor for tourism in the urban context. Heritage restoration projects carried out by professionals have made monuments accessible and presentable again. Many NGOs and professionals have also been engaged in creating heritage walks and other interesting outreach projects to reach out to masses. Heritage has become localised with cultural festivals being organised on several occasions—like e.g. the Kala Ghoda Arts Festival in Mumbai.[3] However, the heritage practice in the country remains primarily within the government purview—except urban heritage which has some element of privatisation. It is a top-down bureaucratic approach rather than a bottom-up, grass-roots level implementation and stakeholders participatory process, and thus lacks inclusivity and diversity. In recent years, public-private partnerships are on the rise, which have offered a boost to heritage conservation and presentation.

Nostalgia of the Past and Packaged Authenticity

Heritage is celebrated in India largely as an achievement of the past and reflects in its presentation as well. At many sites, interpretation infrastructure, such as guided tours, light and sound shows, and interpretation panels has been developed. However, narrow-focused and limited information and eulogistic narratives often interlaced with myths and misconceptions create a romantic experience for tourists, devoid of nuances of history and critical reflection of the past. Visitor experience at historic sites and museums is influenced by “packaged authenticity”, a created narrative. This notion, borrowed from the western discourse, creates a challenge in presenting narratives.[4] Multiple temporalities and spatialities, though visible on sites, are barely taken cognisance of in these narratives. Many heritage projects that deal with colonial heritage seem to harness colonial nostalgia in presentation and preservation. The media use of colonial nostalgia has an appeal for domestic tourists.[5]

Which history is promoted and how it is presented depends on a number of aspects, including official, political and expert preferences. There are also differences in how sites are promoted as heritage. World heritage sites have received attention as key tourist attractions,[6] but a large number of sites remain neglected. Sites are either restored to achieve visual integrity or large infrastructure-related developments around the site. A holistic integrated heritage development plan is yet missing from the imagination and implementation of the historic site managers. Lack of official and expert attention, paucity of funding and infrastructure, and community apathy seem to stall developments.

There is a lot of imbalance in how heritage is valued and developed for commercial purposes, such as tourism. As an example, on one hand, there is commercialisation of heritage sites like the forts and palaces in Rajasthan, while forts in the state of Maharashtra are still waiting to be rejuvenated. Though rampant commercialisation needs to be avoided, many activists are trying for due infrastructure and interpretation to communicate this rich past to the public.[7] Many such cases abound.

Museums are other key sites where history is presented for the public. The museums in India created during the British colonial rule became the cabinets of curiosities to store and display the antiquaries of India, such as sculptures, art and archaeological objects, weapons and botanical/ zoological/ geological specimens. History of India was presented as a linear narrative in these museums starting from prehistoric times to medieval ages. The museum as an institution has transformed in the post-independence period, however the narrative still remains largely uncontested and unreflected. Despite a call for change in museum interpretation, the process is quite slow and interpretation facilities remain inadequate. The museum audience has diversified from the predominantly urban elite as was previously seen, but whether museums have adapted to cater to these larger tourist demands remains to be questioned.

Tell Me Again: What is Heritage?

In India, heritage, in a common parlance, is still something distant for people from their everyday life, something from the past. The notion of living heritage—religious places, industrial heritage such as railways—is not yet well established as heritage for commoners. The Indian heritage practice is still largely concentrated on built forms and monumentality in which visual integrity and material authenticity hold the large focus. Though exceptions exist, change and continuity as essential aspects of heritage are not yet completely ingrained in heritage understanding.

While INTACH advocates sites as fluid and changing, there are only a few examples which show this approach being used in practice. INTACH has largely focused on non-official sites, which has created binaries in the Indian heritage practice. Heritage still remains an isolated and elite phenomenon, seen as contradicting development and progress. Heritage as not just a built or intangible product, but as a political process and practice of creating meanings and values remains less reflected on. A unilateral lens of looking at heritage creates difficulties as the narratives are determined by these authorised perspectives.[8] The everyday, mundane dimension of heritage, community connections, is not well integrated in heritage interpretation.

This is not to say that efforts are not underway in this direction. There have been significant projects, such as the restoration of Humayun’s Tomb in Delhi,[9] which present good examples of close cooperation with stakeholders. Heritage conservation in Mumbai has also taken into consideration the community connection. The UNESCO World Heritage inscription for the Victorian and Art Deco Ensembles in Mumbai was initiated by citizens residing in many of these historic buildings and they have been actively engaged in presenting the narrative of the site.[10]

In recent years, it is encouraging to see that museums harness new concepts of engaging with the public through novel educational and outreach activities. In the case of leading museums like the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya in Mumbai, Indian Museum in Kolkata, extensive programmes are organised regularly for diverse audiences, including school children. The encounters with India’s past, its culture and its future are interlaced in these programmes, engendering critical thinking and engagement among audiences. Moreover, many non-conventional museums, such as Conflictorium in Ahmedabad,[11] Partition Museum in Amritsar,[12] or Bhopal Gas Tragedy memorial in Bhopal[13] have been established in the last decade. These places offer visitors a chance to engage with and reflect on difficult histories.

Way Forward

Measuring success of public history and tourism in India first needs assessing the parameters of success. While the field has achieved a lot over the past few decades, there is much more potential that remains untapped. The Government of India recently constituted a Working Group to assess the challenges in heritage management, in which heritage tourism forms a major component.[14] Improving infrastructure, branding and digital opportunities are among the concerns addressed in this action plan. Along with these developments, what is required is rethinking the role of heritage in development.

As mentioned elsewhere, heritage tourism cannot be an end in itself, but a tool towards socio-economic-environmental sustenance.[15] Heritage practice also needs to be treated with sensitivity, bringing out the plurality, community connections and layered histories, and tangible and intangible connections to the sites. But at the same time, it has to look towards the future, paving the way for social and environmental resilience and well-being. Tourism, not exploitative but rather adaptive, can become a sustainable vessel for propagating public history using inclusive and participatory mechanisms.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Chowdhury, Indira, and Srijan Mandal. “East of the West: Repossessing the Past in India.” Public History Review 24 (2017): 22–37.

- Jørgensen, Helle. “Postcolonial Perspectives on Colonial Heritage Tourism: The Domestic Tourist Consumption of French Heritage in Puducherry, India.” Annals of Tourism Research 77 (2019): 117–27, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.05.001.

Web Resources

- A.G. Krishna Menon, “The Case for an Indian Charter,” n.d., https://www.india-seminar.com/2003/530/530 a.g. krishna menon.htm (last accessed 8 May 2023).

- Kavita Singh, “A New Museum for a New Nation, by Kavita Singh, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India” (Ellen Bayard Weedon Lecture on the Arts of Asia, Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia, 2022), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cW7kKch4TEI (last accessed 8 May 2023).

_____________________

[1] The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), under the Ministry of Culture, Government of India, is the premier organisation for archaeological research and protection of the cultural heritage of the nation. It was founded in 1861 under the British Raj with the intention of surveying Indian antiquities and monuments.

[2] INTACH is Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage, founded in 1984 as a registered society. At their convention in 2004 INTACH proposed a charter for India called “Charter for the Conservation of Unprotected Architectural Heritage and Sites in India”. “INTACH Charter,” n.d., http://www.intach.org/about-charter.php (last accessed 29 March 2023).

[3] “Kala Ghoda Arts Festival,” n.d., https://kalaghodaassociation.com/ (last accessed 31 March 2023). Kala Ghoda Arts Festival taking place in Mumbai every year since 1999 is one of the pioneering examples of cultural festivals organised with the aim of promoting awareness about heritage and culture of the city.

[4] Sanaeya Vandrewala, “Borrowed Notion of Authenticity: Viewing Authenticity of Historic Houses in India Using a Western Lens,” A Journal for Museum and Archives Professionals 16, no. 1 (2020): 60–69, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1550190620903313 (last accessed 8 May 2023).

[5] Ranjan Bandyopadhyay, “‘To Be an Englishman for a Day’: Marketing Colonial Nostalgia in India,” Annals of Tourism Research 39, no. 2 (2012): 1245–48, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.12.004.

[6] “India,” n.d., https://whc.unesco.org/en/statesparties/in (last accessed 8 May 2023).

[7] Vijay Singh, “Improve Public Services for Raigad Fort, City Activist Writes to Maharashtra CM Uddhav Thackeray,” Times of India, 2019, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/navi-mumbai/improve-public-services-for-raigad-fort-city-activist-writes-to-maharashtra-cm-uddhav-thackeray/articleshow/72928168.cms (last accessed 8 May 2023).

[8] Laurajane Smith, Uses of Heritage (London: Routledge, 2006).

[9] Ratish Nanda, “Humayun’s Tomb: Conservation and Restoration,” in Authenticity in Architectural Heritage Conservation. Discourses, Opinions, Experiences in Europe, South and South East Asia, ed. Katharina Weiler and Niels Gutschow (Heidelberg: Springer International Publishing, 2017).

[10] “Victorian Gothic and Art Deco Ensembles of Mumbai,” n.d., https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1480/ (last accessed 28 March 2023).

[11] “Conflictorium, Museum of Conflict, At The Museum,” n.d., https://www.conflictorium.org/at-the-museum/ (last accessed 22 March 2023).

[12] “Partition Museum,” n.d., https://www.partitionmuseum.org/ (last accessed 22 March 2023).

[13] “Remember Bhopal Museum,” n.d., https://rememberbhopal.net (last accessed 22 March 2023).

[14] “Working Group Report on Improving Heritage Management in India,” 2021-22. https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2020-06/Improving-HeritageManagement-in-India.pdf (last accessed 23 March 2023).

[15] Shraddha Bhatawadekar and Mrinal Pande, “Rethinking Urban Heritage Tourism Practices in India: Critical Perspectives From Europe,” in Indian Tourism: Diaspora Perspectives, ed. Nimit Chowdhary, Suman Billa, and Pinaz Tiwari (United Kingdom: Emerald Publishing Limited, 2022), 111–24.

_____________________

Image Credits

Kala Ghoda Arts Festival, Mumbai. © by Shraddha Bhatawadekar, 2023.

Recommended Citation

Bhatawadekar, Shraddha, Sanaeya Vandrewala: Public History & Tourism: Practices in India. In: Public History Weekly 11 (2023) 4, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21498.

Editorial Responsibility

Copyright © 2023 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 11 (2023) 4

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21498

Tags: Asia (Asien), Cultural Heritage (Kulturerbe), India (Indien), Tourism (Tourismus)

To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

OPEN PEER REVIEW

Participatory public history practices – what’s about Yoga?

Many thanks to Shraddha Bhatawadekar and Sanaeya Vandrewala for their insights into how cultural heritage and public memory are practised in India these days. Having visited the country and experienced its rich culture a few times myself, their insider’s view caught my interest.

Dating back to the colonial past, it is not surprising that top-down principles and westernized approaches continue to prevail in public dealings with India’s heritage and memory. This concerns not only material culture but also intangibles. The claim “decolonise Yoga” just popped into my mind while reading the article. I stumbled on this while looking for a Yoga class in Berlin some time ago. Consuming Yoga (or what I thought it was) for many years myself, I have never considered it as cultural appropriation. It was the podcast “Yoga is dead,” co-hosted by Indian-Americans Tejal Patel and Jesal Parikh, which drew my attention to this aspect.[1] Under British rule, ancient Indian customs and practices such as Yoga and Ayurveda were banned. During the 20th century, modern Yoga became popular in the West when entrepreneurial gurus brought it to a capitalistic global market as a fitness brand for high-performing city dwellers. Today, thousands of Yoga studios populate the western world, highlighting the persisting power imbalance between those who have access to wealth and privilege in contrast to those who have been historically marginalised.

Back to India: Yoga and its culture might be one of the country’s major tourist attractions as the many courses, teacher trainings and publicly accessible ashrams suggest. However, what I have found quite fruitful, and inspiring, is how Yoga is embedded in everyday life, even in the smallest communities. In India, I have experienced Yoga as a holistic way of life rather than as a fitness course. I am wondering whether Yoga — among other practices — might contribute to creating a more plural, multi-layered and community-based heritage. Ultimately, it might be able to connect a touristic interest with including local people, and enabling their participation, to initiate and perhaps achieve at least a “breeze of change.”

[1] https://www.yogaisdeadpodcast.com/ (11/4/2023).

To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

Heritage sites without history?

India received 6.19 million Foreign Tourist Arrivals (FTAs) during 2022. Tourism has recovered relatively well from the losses of the Covid pandemic (during pre-pandemic year 2019 there were 10.93 million FTAs in India), as stated from the Ministry of Tourism in April 2023. To boost the tourism sector in the country and to increase foreign tourist arrivals, the Ministry of Tourism has taken several initiatives: First in the statement is the launch of the so called “Dekho Apna Desh initiative” with the objective of creating awareness among the citizens about the rich heritage and culture of the country and encourage citizens to travel within the country. Another goal is to develop and implement the “Incredible India Tourist Facilitator Certification Programme”, a digital initiative that aims at creating an online learning platform with the objective of creating a pool of well trained professional tourist facilitators across the country to support tourists. Also, important tourism sites and facilities are being upgraded to international standards.

The tourism sector has always been of utmost importance for India. The government is putting a major focus on steadily growing it. As Shraddha Bhatawadekar and Sanaeya Vandrewala show in their paper, in recent decades heritage became a big contributor for tourism, especially in the urban context. Heritage sites and museums are important places where the public engages with history in India. The fact that many heritage restoration projects have made monuments accessible and presentable again and that projects like heritage walks contribute to reach out to the masses, is undoubtedly a positive development. Nevertheless, as the authors point out, heritage practice in the country remains primarily within the government purview: “It is a top-down bureaucratic approach rather than a bottom-up, grass-roots level implementation and stakeholders participatory process, and thus lacks inclusivity and diversity.”

In analyzing the relevance and potential of public history and tourism, several points are highlighted that (continue to) have an inhibiting or detrimental effect on the fruitful linkage of the two areas. For example, there is still a great imbalance in how India’s cultural heritage is valued and developed for commercial purposes, especially for tourism. While world cultural sites and forts and palaces such as those in Rajasthan have received great attention, many other important sites remain neglected.

One of the biggest issues is, that in India, heritage is still something very distant from people’s everyday life. My father, who was born and grew up in India, describes his perceptions that while certainly a large number of visitors from India and abroad travel to heritage sites (mostly in the form of a family vacation), engagement with the history of the sites often plays little or no role. He confirms that the narratives conveyed are sometimes uncritical, embellished with myths instead of multi-perspectivist information, and that the focus of the sites is often on impressive light and sound installations.

As Bhatawadekar and Sanaeya conclude, with public history and tourism there is much potential that remains untapped. Dealing with the past through heritage sites and museums should be used not only for entertainment but also for education. In any case, history must create and authenticate identity; it must provide insight into the identity of local people. “Heritage practice also needs to be treated with sensitivity, bringing out the plurality, community connections and layered histories, and tangible and intangible connections to the sites. Tourism, not exploitative but rather adaptive, can become a sustainable vessel for propagating public history using inclusive and participatory mechanisms.” (Bhatawadekar/Sanaeya). Whether it goes step by step in this direction, I will try to review during my next trips to India.