Abstract: Thirty years of violent conflict in Northern Ireland, a stuttering, if enduring, peace and the unaddressed issue of legacy combine with a society quickly evolving in diversity and social values, to provide a dynamic if unstable environment in which to examine the difficult past. For educators, that context is made more complex by communal division in the education system which is over 90% segregated between those from unionist/Protestant and nationalist/Catholic backgrounds.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21809

Languages: English

Pre-1968, Northern Ireland history teaching displayed the content driven, rote learning characteristics of Mary Price’s “History in Danger”.[1] We can only speculate as to how far partisan or inadequate history teaching contributed to division which exploded into violence. Whatever past grievances – real, exaggerated, imagined, distorted – were ingrained in social and political structures on each side of the community, history teaching did not do enough to challenge each side’s myths and partial truths.[2]

Refractions and Reflections

My writing here is more personal reflection than professional thesis. Alongside glaziers and undertakers, I have shaped a career out of the NI conflict. I was an A level student between 1968 and 1970 during the civil rights campaign when the conflict kicked off. For most of the Troubles period, I was a classroom teacher in a strongly loyalist area. From 1995, encompassing the peace process and post Good Friday Agreement years, I was a teacher educator.

As practitioner and researcher, I have lauded the way many in the history teaching community in NI have responded to division by developing approaches which challenge the history of the streets. However, increasingly, I have become frustrated at our collective failure to build on progress by carrying the work forward into mainstream schooling.

The Emergence of Disciplinary History

For educators who wished to play a pro-active role in challenging sectarianism, the medium of history had distinct advantages. As well as its possibilities for influencing contemporary attitudes, it had high academic and examination status; and, crucially, it had the potential to access all young people. Two external influences aided risk-takers. The first came via the academic Irish history community. In the second half of the 20th Century that community, north and south, became a forum for dialogue, controversy and revisionism, thus contributing to critical awareness amongst young teachers emerging from universities. The second was the advent of “New History” through the Schools’ Council History Project (SCHP) in England. For a small but significant minority of teachers in NI, SCHP’s emphasis on enquiry, evidence, second order concepts and multiple perspectives offered both an escape from teaching simplistic single narratives and a chance to influence societal change.

The initial NI History Curriculum in 1990 built on over a decade of development work by embedding enquiry into the 11-14 curriculum with the clear intent that it should have a positive influence on community division. It was accompanied by a common core of key events in Irish History to be taught in all schools. Impressive for a society still at war! By the mid-nineties, an external examination module dealing with the recent Troubles period was included in the GCSE programme, albeit as an elective option.

Further research indicated that curriculum changes were having some impact. Kitson concluded that teachers were committed to teaching “as ‘balanced’ a view of the past as they can.”[3] Studies demonstrated that students understood the primacy of evidence when reaching historical judgments and they valued history as offering alternative perspectives to the partisan accounts often heard in the community.[4] Barton and McCully concluded that students, when they encountered multiple sources of information, did so critically even if they often struggled to break free of interpretations dominant in their own communities.[5]

Research also identified other constraints and weaknesses. Students frequently found the history they were taught was too divorced from their everyday experiences, especially when it concentrated on the mechanistic examination of sources. What students sought above all was for history to help them to make sense of the situation around them – yet, too often, they were left to make connections between past and present for themselves with little teacher mediation. Also, students were often presented with dual rather than multiple perspectives, stereotypical unionist and nationalist positions, which lacked nuance and complexity grounded in real lives, and this sometimes convinced them that the conflict was intractable.

Post 1998, younger pupils were receiving inadequate, incomplete accounts of the Troubles at home.[6] They were curious to know more but this was not covered in the junior school curriculum, nor were many teachers prepared to tackle the recent, contentious past. Kitson[7] argued that teachers, not curriculum, was the critical factor governing student experience and that teacher avoidance continued to be a major constraint in the post Good Friday era.

Overcoming Avoidance

Nevertheless, I was optimistic as we entered the second decade of the Millennium. Policymakers were aware of weaknesses and were willing to address them, and an increasingly active civil society was engaging with remembering the momentous Decade of Centenaries, 1912-22 at community level. Optimism was reinforced in 2007 by the introduction of a radical revised 11-14 curriculum. It explicitly promotes history’s role in understanding contemporary NI society and schools are offered flexibility to choose content relevant to the needs of their students within a prescribed framework. Young people are asked to investigate:

- how history has affected personal identity / culture / lifestyle;

- how selective interpretation / stereotyping / abuse have been used to justify views and actions;

- how historical figures have behaved ethically and unethically;

- how the cause and consequences of Irish Partition have influenced modern NI.

Thus, we now had the curriculum, pedagogy and resources, alongside a cohort of skilled practitioners and a growing societal impetus, for history teaching to fulfill its potential as a change agent.[8]

Instead, arguably, the situation has stalled since 2010 with little development toward mainstreaming best practice. The full potential of curriculum is unrealised, and avoidance and containment continue to shape many classrooms.[9] Recent reports have highlighted the failure of education to contribute effectively to the difficult task of dealing with the legacy of the recent past. The Commission on Flags, Identity, Culture and Tradition concluded that “many young people were not given the chance to explore culture, identity and tradition in schools”[10] while research on citizenship education suggested a failure to teach children about the Troubles “leaves the deep-rooted causes of conflict and division untouched.”[11]

There are complex reasons for failing to overcome avoidance and not effectively mainstreaming our considerable knowledge and skills in regard to teaching difficult histories. For a start, teachers are not simply conduits for official curriculum goals. In class, they teach in ways that are consistent with their own values and personal understanding of the purpose of history. They are products of the society in which they teach, and this is especially so in conflict affected societies where external interference from community influences, real or perceived, is feared.

However, not all resistance is externally generated. Controversial issues trigger strong views and teachers must be prepared to facilitate, manage and work through emotional reactions.[12] For teachers, adopting such pedagogy sometimes threatens a key platform of their professional identity, their sense of classroom control. History teaching in NI has relied too heavily on cognitive processes rather than embracing the potential for affective learning to unlock the constraints imposed by upbringings which lack proper perspective on the other community.

There is one further factor which limits horizons, the tyranny of external assessment. Teachers are frequently criticised for their reticence to tackle difficult histories but, in reality, it is not on such matters that they are professionally judged. Predominantly, accountability in the NI school system, both within and between schools, is measured by examination results. It is not surprising that teachers channel their energy into the demanding, but quantifiable, outcomes of exam preparation rather than risking the swamplands associated with teaching the difficult past.

Even the GCSE module on the Troubles, now covering the whole 1968 to 1998 period, has limitations. Arguably, senior students benefit from greater maturity when encountering the contested past and its contemporary ramifications. However, teaching the module is subject to considerable pressures imposed by content delivery and time. Its political focus provides little space for exploration of, and dialogue on, ordinary peoples’ experiences, which is where today’s sensitivities to the Troubles usually rest. Further, examination culture drips down to stifle the transformative aspirations of the junior history and citizenship curricula.

Personal Reassessment

So how can we balance the factors identified above –the past with the present, the cognitive with the affective, and exams with contemporary relevance? Those challenges have caused me to re-think two of my previous maxims; the first is that my faith in disciplinary boundaries, including that history and citizenship are connected but distinct, has been questioned. I now believe that greater inter-disciplinary flexibility between history and the social studies is required if students are to meaningfully explore history’s contemporary relevance. Only when students understand powerful emotions associated with cultural identity, symbolism, legacy and loss can they better explore why studying history can be emotive and contested.

My second re-think relates to external examinations. I have come to realise the futility of blaming exams for taking teachers’ and students’ attention away from history’s extrinsic, societal role. Examinations are an established part of the education system and have their own social utility. They are motivationally powerful. Therefore, why not seek to modify current exam practice by endorsing content and approaches that would provide students with greater opportunities to engage with the human aspects of past events and their contemporary significance?

For example, why not re-vamp the GCSE NI Troubles module by creating two strands? First, students might examine political events, 1968-98, as an outline framework and then study in-depth the social history of the period by concentrating on the impact conflict had on people’s lives – including the families of politicians, combatants, victims and ordinary citizens. In addition to using printed and visual sources this would allow for the use of oral evidence and visits to national and contemporary museums. All lend themselves to rigorous historical enquiry. The second strand would focus on contemporary relevance in relation to issues such as cultural identity, how history is used and abused, dealing with legacy of conflict and how we remember and commemorate. In the current century, an impressive academic literature has built up around remembrance, memorialisation and commemoration which can give rigour to such studies.

Realistically, examination teaching always imposes constraints, but I argue that the module as outlined above could be a catalyst for changing teacher practice. It has the potential to better meet the needs of young people by giving them insight into the troubled past but also into why that past continues to inhibit social progress in the present. Of course, my proposal will meet resistance but is there not a growing momentum in the UK generally that external examination provision requires reform? I also wonder how far the past / present structure (including investigating remembrance, commemoration and contemporary representations of the past) might be relevant to wider studies of empire, colonialism and warfare in other parts of the UK?

_____________________

Further Reading

- McCully, A. & Waldron, F.. “A question of identity? Purpose, policy and practice in the teaching of history in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.” History Education Research Journal 11(2), 145-158 2013. DOI: 10.18546/HERJ.11.2.12

- Kitson, A., & McCully, A. “‘You hear about it for real in school.’ Avoiding, containing and risk-taking in the history classroom.” Teaching History, 120 2005, 32-37.

- McCully, A. W.. “Teaching history and educating for citizenship: Allies or uneasy bedfellows in a post-conflict context?” In T. Epstein & C. Peck (Eds.), Teaching and learning difficult histories in international contexts: A critical sociocultural approach (216-234). New York: Routledge 2018.

Web Resources

- Flags report: Stormont publishes £800k report without action plan https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-59266116 (last accessed 27 June 2023).

- History Education in the Northern Ireland Curriculum: Alan McCully https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-EEPRBL0BJg (last accessed 27 June 2023).

- A Decade of Anniversaries Schools Resource https://www.creativecentenaries.org/toolkit/case-studies/a-decade-of-anniversaries-schools-resource (last accessed 27 June 2023).

_____________________

[1] Mary Price (1968) History in Danger, History, 53:179, 342-347<

[2] Dominic Murray, (1985) Worlds Apart: Segregated Schools in Northern Ireland. Belfast: Appletree Press. Milliken M., Bates J. and Smith A. (2020) Teaching Across the Divide: perceived barriers to the movement of teachers across the traditional sectors in Northern Ireland, British Journal of Educational Studies, 69: 2, 133-154

[3] Alison Kitson, 2007) History Education and Reconciliation in Northern Ireland, in Elizabeth A.Cole (ed.) Teaching the Violent Past: History Education and Reconciliation. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 123-153

[4] Keith C. Barton and Alan McCully, (2005) History, Identity and the School History Curriculum in Northern Ireland: An Empirical Study of Secondary Students’ Ideas and Perspectives, Journal of Curriculum Studies, 37(1), pp. 85-116. John Bell, Ulf Hansson, and Neil McCaffery, (2010) The Troubles Aren’t History Yet: Young People’s Understanding of the Past. Belfast: Community Relations Council.

[5] Keith C. Barton, and Alan McCully (2010) “You can form your own point of view”: Internally persuasive discourse in Northern Ireland Students’ encounters with History, Teachers’ College Record, 112:1, 142-181.

[6] Bell et al. “The Troubles aren’t History”

[7] Kitson, “History Education and Reconciliation”

[8] See Creative Centenaries https://www.creativecentenaries.org/

[9] Alison Kitson and Alan McCully (2005) ‘You hear about it for real in school.’ Avoiding, containing and risk-taking in the classroom, Teaching History 120, 32-37

[10] Executive Office (2021) Commission on Flags, Identity, Culture and Tradition: Final report, Belfast: https://www.executiveoffice-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/execoffice/commission-on-fict-final-report.pdf

[11] Una O’Connor, Elizabeth A. Worden, Jessica Bates and Vanessa Gstrein (2020) Lessons learned from 10 years of citizenship education in Northern Ireland: A critical analysis of curriculum change, Curriculum Journal, 31:3, 479-494.

[12] Michalinos Zembylas, 2017, Wilful Ignorance and the Emotional Regime of Schools, British Journal of Educational Studies, 1-17/small>

_____________________

Image Credits

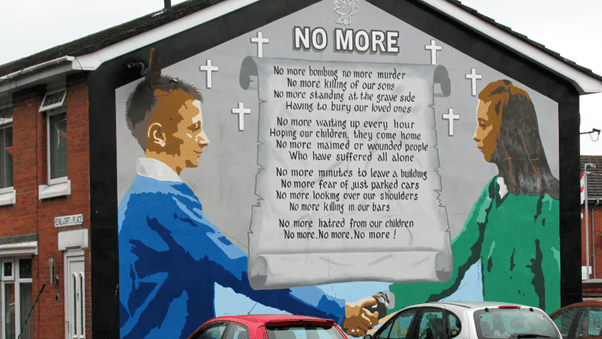

Mural depicting children from opposite communities in east Belfast shaking © 2018 Tom Bastin CC BY-2.0 via Hansard Society.

Recommended Citation

McCully, Alan: Teaching Difficult Histories and Countering Avoidance. In: Public History Weekly 11 (2023) 5, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21809.

Editorial Responsibility

Copyright © 2023 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 11 (2023) 5

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21809

Tags: Conflict of Memory, Curriculum (Lehrplan), Difficult Histories, Northern Ireland, Speakerscorner

To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

OPEN PEER REVIEW

A Model Approach and a Work in Progress

In this interesting article, the author initially discusses how the implementation of a disciplinary approach was welcomed as a promising way to equip students with the necessary tools to navigate through the contrasting narratives prevalent in Northern Ireland. As per the author’s account, their anticipations were only partially met. Empirical research suggests that this methodology did enable students to conceive history as an investigative process, whereby historical judgments necessitate substantiation through evidence. Also, despite students grappling with moving beyond the prevailing narratives within their communities, they were nonetheless able to critically analyse varying interpretations.

However, the author contends that the full potential of the disciplinary approach remains unfulfilled, primarily due to avoidance. This phenomenon is characterised by teachers shying away from disputed, sensitive topics that, ironically, are most pertinent to their students’ everyday experiences. The examination system exacerbates this problem by placing an emphasis on ‘content delivery and time’, thereby deterring teachers from focusing on the sensitive past. The author suggests that in order to overcome avoidance, more space should be given to the study of how emotions affect the way we see our past. In terms of the limitations imposed by examinations, they suggest that recalibrating examinations, in order to include content and approaches related to sensitive and societal issues, can be a more fruitful approach than simply seeking to abolish them.

The case of Northern Ireland has many similarities with the case of my country, Cyprus (i.e. internal conflict in the past, existing tensions, segregated education systems, conflicting dominant narratives within the main communities). There are also important differences. The current political division in Cyprus means that the two major communities of the island, Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots, live separately in areas controlled by different authorities. As expected, two different educational systems exist on the island. Finally, in the realm of history education, we encounter a dichotomy. On one side, in both systems, the official policy promotes the adoption of constructivist methodologies, as outlined in the curricula, which are designed to cultivate a deep understanding of the discipline and abilities of historical investigation. However, on the flip side, the mandated factual content that must be taught, as also specified in the curricula, continues to be characterised by a narrow, one-sided view, mainly focused on a single cultural or national perspective. Moreover, in both education systems, the standard textbooks used tend to rely on traditional methods of knowledge transmission, with limited emphasis on fostering ideation related to disciplinary historical thinking, or the abilities required for constructing a nuanced understanding of historical events and phenomena.[1] Taking into consideration the central place of history textbooks in both education systems in Cyprus, despite the curriculum advocating for a constructivist teaching approach, teachers are more likely to gravitate towards the conventional methods presented in the textbooks.[2]

In the light of the above, it can be argued that the example of Northern Ireland can serve as a model for Cyprus. Implementing a disciplinary approach could help Cypriot students view history as a means to investigate the past rather than a subject for rote memorization. It could further foster critical thinking around conflicting narratives. However, the phenomenon of teachers’ avoidance of controversial issues also exists in Cyprus.[3] In this sense, fully harnessing the potential of a disciplinary approach is still a work in progress in both countries.

The author’s call for placing greater emphasis on helping students comprehend the role of emotions in contested narratives may seem like a shift away from disciplinary approaches focusing on cognitive aspects of history. However, I do not think that this is what the author suggests. This is because a disciplinary approach does not disregard the role of emotions. As Peter Lee, one of the most prominent advocates of the disciplinary approach in history education, points out if we ‘treat people in the past as less than fully human and do not respond to those people’s hopes and fears, …[we]… have hardly began to understand what history is about’.[4] Consequently, the aim should not be to strike a balance between cognitive and affective aspects, but to include emotions in the factors that form past and present perspectives. This has the potential of helping our students to view the emotions of people in the past (and the present) as reasonable human reactions to specific events and conditions that led to specific views and behaviour, rather than explaining them simply in terms of right or wrong, good or evil.

_____

[1]Perikleous, L., Onurkan-Samani, M., and Onurkan-Aliusta, G. (2021). Those who control the narrative control the future: The teaching of History in Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot schools. Historical Encounters, 8(2), pp. 124-139. https://doi.org/10.52289/hej8.207

[2] Ibid.

[3] Zembylas, M. and Kambani, F. (2012). The Teaching of Controversial Issues During Elementary-Level History Instruction: Greek-Cypriot Teachers’ Perceptions and Emotions. Theory and Research in Social Education, 40(2), pp. 107-133. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2012.670591

[4] Lee, P. J. (2005). Putting principles into practice: understanding history. In M. S. Donovan and J. D. Bransford (Eds), How Students Learn: history, mathematics and science in the classroom. National Academy Press; p.47

To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

A starting point for change

This is a masterful synthesis of what Northern Ireland has to teach us about history education—and a concise one. (Word limits are the scholar’s best friend.) It’s hardly surprising that I can find nothing to disagree with in McCully’s analysis of the situation, since so much of my own understanding of Northern Ireland, and history education, has developed in collaboration with him—and often under his tutelage. I certainly do not disagree with his assessment that disciplinary history, while it may be a necessary requirement for socially-useful history education (and far better than nationalistic, sectarian, or mythical history) is not sufficient for such purposes. In a sense, disciplinarity “underdetermines” the outcome of the subject, because it can be used in ways that have little do with the real issues that we face in society. As Li-Ching Ho and I have argued, the “building blocks” approach to curriculum does not work very well: “Learn this now, and use it in meaningful ways later.” (1)

Crucially, McCully recognizes three factors as standing in the way of history’s potential: 1) teachers’ own goals and values, particularly related to the purpose of their subject; 2) teachers’ desire to maintain control, by avoiding controversy and the emotions it creates; 3) the content of exams. His rethinking of assumptions emphasizes the third element: Reform the exams so that they focus more clearly on history’s societal purpose. This would become the catalyst for changes in practice. Of this, I am less convinced. The role of examinations if very different in the United States than in most of the English-speaking world, yet there may be some parallels that are instructive. In the 1990s, many of us in the United States thought that if examinations were changed (for example, to better reflect inquiry-oriented approaches), then instruction would necessarily follow. We were wrong. Instead, teachers interpreted the content of exams in ways that reflected their own prior ideas, and continued teaching in the way they always had. Eventually (and fairly quickly), exams themselves largely reverted to their prior forms. In the words of S.G. Grant, exams were “an uncertain lever” of change. (2)

I’m increasingly convinced that the starting point for change must be one of the other factors that McCully points to: teachers’ ideas about the purpose of the subject. To some extent, I’ve long believed that only if teachers want to do things differently will they be willing to take the risk of doing so. But I now believe this sense of purpose must be a collective one, rather than an individual one. In the United States, when history teachers are asked for their ideas about the subject, they always respond, “I think that…” I’m not sure that these individualistic and isolated ideas will ever be a catalyst for change—especially since they can easily be suppressed in the face of public opposition.

But Hana Jun, a doctoral student at Indiana University, found a different response when talking with history teachers in Korea. She asked them what they would do if the topic of “comfort women” (victims of sexual exploitation by the Japanese military) were removed from the official curriculum. Teachers said they would continue to teach about the topic, but they began their responses with, “As history teachers…” Their justifications, that is, rested not on their individual ideas but were rooted in their collective sense of responsibility as history teachers. (3)

Perhaps, in Northern Ireland and elsewhere, this is what we need: A sense of purpose that is not individual but that is collective. Now, to some extent I think that already exists in Northern Ireland and throughout the United Kingdom: History teachers believe that their collective purpose is to teach disciplinary approaches, and this has provided a means of standing up against attempted nationalistic revisions to the curriculum (in England). But if the goal is for history to address societal division, then teachers’ purpose (and not just the content of exams) must extend beyond disciplinarity. Teachers must collectively develop a reason to take risks, address controversy, allow emotional reactions, and so on. But that’s not going to be easy.

(1) Barton, K. C., & Ho, L. C. (2022). Curriculum for justice and harmony: Deliberation, knowledge, and action in social and civic education. Routledge, 2022

(2) Grant, S. G. (2001). An uncertain lever: Exploring the influence of state-level testing in New York State on teaching social studies. Teachers College Record, 103(3), 398–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/0161-4681.00120

(3) Jun, H. (n.d.) “If they were history teachers”: Korean history teachers’ sense of curricular agency, identity, and purpose. Unpublished manuscript.

To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

Avoidance as the biggest issue

“Students frequently found the history they were taught was too divorced from their everyday experiences, especially when it concentrated on the mechanistic examination of sources” This is a key point here, I’d say. When kids are surrounded every day by what are basically discourse-shaping tools – murals, flags, parades, just to name the most prominent – it must be hard to engage with the conflict in a way that is maybe new to them, despite schoolteachers’ best efforts. Of course, the importance of the role of the teacher, not only as the one who teaches those topics but also the one who answers students’ questions about it, cannot be overstated here.

Just as Lukas Perikleous underlined in his peer review, the biggest issue seems to be avoidance; yet, the Decade of Centenaries seems to have been used as an occasion to rethink commemorative strategies and engagement, which is definitely a step into the right direction. With today’s schoolchildren not having been alive to witness the “active” years of the conflict (pre-1998), this is hopefully the right time to move towards a more sustainable and balanced teaching of the Troubles.

To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

A great piece

A great piece, strong insights as always from your work. I note the resonant paths we’ve taken with the promise of a (particular) disciplinary interpretation of historical thinking. Though Seixas’ first student in his then newly formed ‘centre for the study of historical consciousness’ my deviance from that premise and promise was via curriculum theory and encountering a disciplinary school’s limits to educate with contentious historical issues still present (e.g., Indigenous-non Indigenous relations). As McCully notes, the affective is not simply a recognition that those past and present have psychosocial emotional lives, but, as I interpret, rather what might be engaged educationally by taking up as a learning our own relations of such to those issues we encounter in schools and beyond. For an exploration of some intellectual tools and application to do so see “Terror management theory and the educational situation” (1).

Another challenge lies in a Euro-American inheritance that education is primarily an epistemological concern, rather than ontological. The former leads to educationalist tinkering with methods whose only real promise is that there will always be need for more books and proposals for ‘the fix’, while the latter invites something more. I will keep this post short but those interested can see den Heyer, “An analysis of aims and the educational ‘event’”(2). For renovations in key historical concepts useful to a more becoming educational hope, see this in press piece for a handbook on social studies research and teaching (3).

I am still thinking about the standardized exam point. Thank you Dr. McCully for your work! And to borrow from Alain Badiou, “keep going!”

(1) Cathryn Van Kessel, Kent Den Heyer & Jeff Schimel (2020) “Terror management theory and the educational situation”, Journal of Curriculum Studies, 52:3, 428-442, DOI: 10.1080/00220272.2019.1659416

(2) den Heyer K. (2015). An analysis of aims and the educational ‘event’. Canadian Journal of Education, 38(1), 1-27.

https://journals.sfu.ca/cje/index.php/cje-rce/article/view/1717

(3) den Heyer, Kent. “A Curricular Reading of Historical Perspective, Agency, and Viral Futures in Social Education”. In press. Available online: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1FCPR68Hoi1X-2ISceUgwhFuGSWt8LiO7.