Abstract: Historical justice and its relationship with historical education are convoluted. This article presents three forms of historical justice posed by social and political theory – that is, retributive, reparative/restorative and transitional justice. It then highlights how the latter, similarly to historical consciousness, aims to foster moral awareness. It concludes that a moral dimension of history is the historicization of public memory.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2022-20122

Languages: English

The relationship between historical justice and historical education is veiled and covered. This article carefully reveals fundamental ideas about justice, and problematizes the relationship between historical discourse and justice.

A Varied History

Historical justice has a varied history that starts with the Nuremberg Trials. A guiding thread that connects the past with the future of historical justice is the gradual transition from punitive practices and sentencing of perpetrators, to the care for the moral and material rehabilitation of victims. Historical justice can also extend to the formation of committees of truth and reconciliation and to efforts that prevent and avert crimes against humanity, in the present and future. These ideas presuppose the use of historical knowledge as a preventive mechanism to overcome the perpetual cycle of suffering, which, in addition, presupposes the mobilization of historical science and education from the perspective of a moral and democratic citizen.

Historical Justice in Social and Political Theory

Historical justice means the urgent demand to investigate the truth about the “dark pages” of history or its significant silences in order to redress the injustices committed against specific social groups. The successful completion of this investigation implies the partial adjustment or overthrow of the historical rule/canon and the replacement or rearrangement of the national narrative, which will be the basis for either national reconciliation or the overcoming of hostile relations between states.

Modern social and political theory distinguishes three forms of historical justice:

1. Retributive justice. Typical examples are the Nuremberg Trials, the enactment of Laws on Historical Memory (France, Poland), national or international trials to clear the traumatic and controversial past (ultimate betrayal, or collaboration with the enemy), as well as sentencing war criminals or crimes against humanity.

2. Reparative / restorative justice. Notably, this form of historical justice, enshrined internationally in the 1949 Geneva Conventions, is not a retroactive form of criminal liability for dark acts and obscure aspects of the past. Restorative justice can take two forms, a financial and a moral one. The latter involves the symbolic redress of defamation, persecution, humiliation, injustice or violence suffered by the victim.

At an intra-state level, the establishment of Truth and Reconciliation Committees in South Africa, following the abolition of racial segregation and exclusion of the black population (1995), is considered the best example of restorative justice (South Africa’s Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Bill). Another typical form of symbolic redress in the context of restoration is the retroactive vindication of 75,000 British gay men in early 2017.

Lastly, manifestations of intra-state redress include the introduction of affirmative action in favor of disadvantaged groups (predominantly in the US), and the renaming of streets and the erection of monuments dedicated to the memory of victims. In a reverse practice, acts of retribution include the destruction of monuments and symbols that have been embodying tyrannical regimes and times of violence, freedom and cold oppression.

3. Finally, transitional justice. This term includes the demand for reconciliation and bridging the social gap. The latter can be achieved, among other ways, through processes of “retrieval” of truth, consultation on cultural symbols and new standards of places of memory.[1] This category[2] includes symbolic political actions, such as the kneeling of German Chancellor Willy Brandt in 1970 in front of the Warsaw Ghetto Monument or the recognition of the French state’s responsibilities for the Vichy Regime by the French President Jacques Chirac in 1995.[3]

Τhe distinguishing feature of transitional justice, that is, the element in which it differs from symbolic restorative justice, is the fact that symbolic actions, such as the kneeling of Willy Brandt in Warsaw, the recognition of political, moral and historical responsibility by Jacques Chirac in 1995 for the semi-fascist and collaborationist regime of Vichy (1940-1944) and the establishment of truth and reconciliation committees, are constituted with the purpose of becoming part of a – possibly long – complete framework of socio-political processes aiming at historical self-knowledge, moral cleansing and, perhaps finally, reconciliation.

Historical Justice, Historical Thinking and Consciousness

In the historical consciousness, there is always an ethical background. For this reason we are obliged to include the moral dimensions of History in the core of the curricula of historical studies, especially the historicization of public memory. It must be noted that in many European countries, such as Belgium, the so-called “memory education” has become an official part of history curricula or interdisciplinary aims and objectives of secondary education.

The term “remembrance education” signifies the recognition of a certain responsibility “for crimes or persecutions that have occurred in the past”, and the knowledge of the “dark chapters” of humanity so as to “prevent the repetition or denial” of these “catastrophic events”.[4] Remembrance education also allows us to express our duty as citizens to fight against intolerance, discrimination, racism, xenophobia and human rights violations.[5]

Finally, for this analysis, we refer to Roger Simon’s approach, which is based on the thinking of Benjamin, Levinas, Derrida and Homi Bhabba. His approach is an original and radical form of critical pedagogical memory.[6] Simon defines historical consciousness as a form of moral awareness, which brings into the present traces points of the past (texts, material remains, artifacts, photographs, oral testimonies, etc.).[7] Simon believes that historical sources are not mere constellations of historical information. Crossing them, we cross the space-time borders and dive into the painful experience of the people of the past: we listen to their plural voices and give them space in our own mental and psychological universe.[8]

Such an approach transforms history into a field of constructing a new sociopolitical responsibility and public morality, which, while treating the past in both historical and moral terms, is not content with the task of memory (i.e. the “I Do not Forget” [Δεν Ξεχνώ] demand in Cyprus).[9] On the contrary, it transforms the bitter aftertaste of the past into a power of understanding the inequalities, conflicts and antinomies of the present on the one hand, and into a creative impulse for a future of emancipation and justice on the other hand.

In this light, the past as an “absent presence”[10] no longer haunts the present, but “reconciles us to its ghosts”,[11] as well as to its diffuse and multiplying otherness, while helping us to perceive its gaps and blind spots of our own identity and historical reading.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Ruti, Teitel. Transitional Justice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Yves, Ternon. Génocide. Anatomie d’un crime. Paris: Armand Colin, 2016.

- Allan, Thompson, ed. Media and Mass Atrocity. The Rwanda Genocide and Beyond. Waterloo: Centre for International Governance Innovation, 2019.

Web Resources

- Όμιλος για την Ιστορική Εκπαίδευση στην Ελλάδα – Association for History Education in Greece. https://aheg.gr/(last accessed 30 May 2022).

- Μνήμες από την Κατοχή στην Ελλάδα [Memories from Occupation in Greece]. https://www.occupation-memories.org/(last accessed 30 May 2022).

- Ελληνική Εταιρεία Ιστορικών της Εκπαίδευσης [Greek Society of Education Historians]. https://www.eleie.gr/el/ (last accessed 30 May 2022)

_____________________

[1] John D. Brewer, David Mitchell, and Gerard Leavey, eds., Ex-Combatants, Religion and Peace in Northern Ireland. The Role of Religion in Transitional Justice (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 155.

[2] The following actions could also be considered as forms of transitional justice, but focused on public apology:

a) The establishment of a “National Sorry Day” in Australia in 1998, in remembrance of the discrimination against Aboriginal people;

b) the 1997 apology of US President Bill Clinton to the survivors of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. This massive experiment was conducted in the state of Alabama during the forty years of 1932-1972 against poor African-American farmers without their consent, and as early as the mid-1940s the treatment of syphilis with penicillin was successfully applied; and,

c) the Belgian confession (2002) of their role in the assassination of Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba. The action followed suit with the initiative taken in 2005 by the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Brussels: in particular, it reviewed the entrenched colonial political memory, as well as the relevant historical and museological strategies that legitimized the organization and organization of collections.

For all the above examples, see details in the exhaustive and multidimensional book of Elazar Barkan, and Alexander Karn, eds., Taking Wrongs Seriously. Apologies and Reconciliation (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006).

[3] On the different categories of historical justice see Elazar Barkan, and Alexander Karn, “Group Apology as an Ethical Imperative,” in Taking Wrongs Seriously. Apologies and Reconciliation, eds. Elazar Barkan, and Alexander Karn (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006), 3-30. On transitional justice specifically, see: Neil J. Kritz, ed., Transitional Justice. How Emerging Democracies Reckon with Former Regimes, volume I: General Considerations, volume ΙΙ: Country Studies, volume ΙΙΙ: Laws, Rulings, and Reports (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 1995).

[4] Karel Van Nieuwenhuyse, “‘Remembrance Education’ and the Historization of Holocaust Memories in History Education,” International Society for History Didactics, Jahrbuch 2012, 207-210.

[5] Karel Van Nieuwenhuyse, ibid.

[6] Kent Den Heyer, “A Dialogue on Narrative and Historical Consciousness,” in Theorizing Historical Consciousness, ed. Peter Seixas (Toronto / Buffalo / London: University of Toronto Press, 2004), 202.

[7] Kent Den Heyer, ibid., 203.

[8] Roger I. Simon, ibid., 189.

[9] “Δεν Ξεχνώ”, meaning “I Do not Forget”, has become the key slogan of Greek Cypriots in the years following 1974. As Christodoulou (2021) points out, the “I do not Forget policy” focused on keeping alive the collective historical memory of the invasion, the refugees, the human rights abuses and the sot lands in order to be able to claim them back (Christou, 2006); thereby, historical memory became synonymous with the pursuit of historical justice. See: Eleni Christodoulou, “Textbook Revisions as Educational Atonement? Possibilities and Challenges of History Education as a Means to Historical Justice,” in Historical Justice and History Education, ed. Matilda Keynes, Henrik Åström Elmersjö, Daniel Lindmark and Björn Norlin (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021), 215-248.

[10] Roger I. Simon, ibid., 187.

[11] Roger I. Simon, ibid., 187.

_____________________

Image Credits

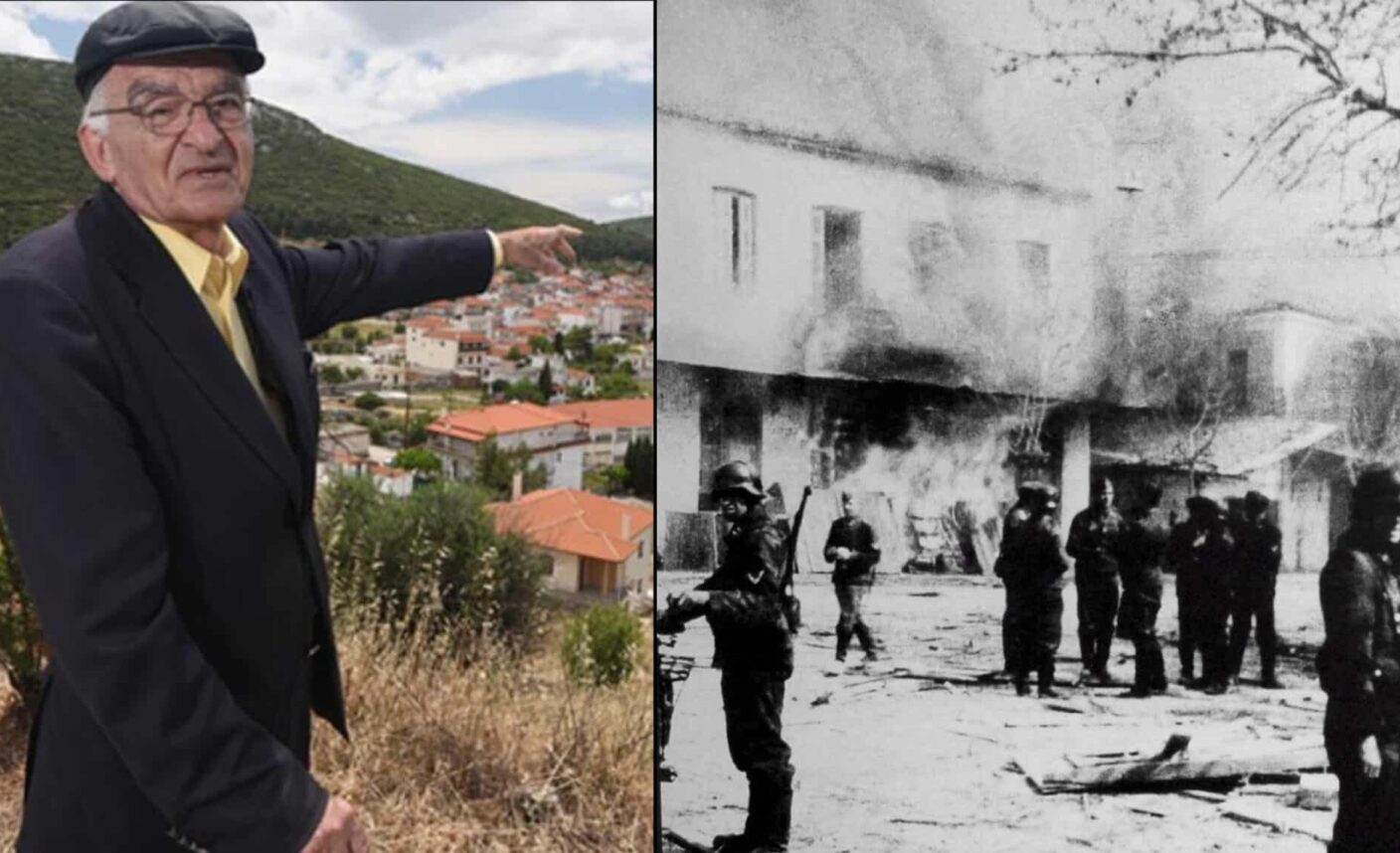

Argyris Sfountouris is a survivor and a reparations activist of the massacre of the village of Distomo on 10th June 1944 by the Nazis.

© Collage of two photos by PHW staff.

Recommended Citation

Kokkinos, Georgios: On Historical Justice and History Education. In: Public History Weekly 10 (2022) 5, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2022-20122.

Editorial Responsibility

Copyright © 2022 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 10 (2022) 5

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2022-20122

Tags: Greece (Griechenland), Historical Justice, History Education (historische Bildung), World War II (Zweiter Weltkrieg)

To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

I think this is a really interesting piece and shows that in England, we have not really come to grips with these issues. Instead, we often talk about teaching ‘controversial’ and ’emotional’ history and miss the ethical dimension when talking about second-order concepts.

In my view, it means that we have to shoulder the blame for the poor state of public discourse around Empire and the human wrongs that we have committed. I’d be really interested in your view on the work of Michael Rothberg in relation to these issues.

To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

OPEN PEER REVIEW

A More Direct Access

This is a quite interesting essay that attempts a discussion of the relation between the concept of historical justice and the teaching of history. Following a brief description of three different forms of historical justice, which deal with the traumatic past in different ways (retribution, reparation and reconciliation), the article argues that historical consciousness has a moral/ethical aspect which can contribute to historical justice. This aspect has to do with an ethical responsibility of contributing to the prevention a) of the repetition or b) the denial of past traumatic events such as the Holocaust or the injustices against indigenous people in places colonised by the Europeans.

According to the essay this kind of ethical historical consciousness can be pursuit through a history education that focuses on bringing students in touch with the memories of the past as these are conveyed, as suggested by the reference to the work of Roger Simon, by a specific kind of sources of the past, namely testimonial accounts (e.g. diaries, memoires, video testimonies, literature, visual sources). Such accounts are not merely sources of information, but also portals that provide us with a more direct access (compared to the accounts of historians) to the experience of people in the past. Furthermore, these accounts are not to be passively read by students. Instead, they are to be actively interpreted as every other account. In this way, according to the essay, our experience of people in the past becomes not only more complete, but also informs the way we perceive our own identity and narratives of the past.

There are a number of ways to respond to such a thought-provoking piece. However, due to wordage limitations, I will focus only on its connections with what Denis Shemilt (2011) calls a ‘social education approach’, an approach which, as he argues, a) ‘inoculate[s] students against false representations of the past transmitted by tradition and popular culture (p. 105), b) ‘seek[s] to provide students with knowledge and understanding of the past that will remain useful throughout adult life’ (p.105) and helps them make informed decisions that cannot be predicted from our present point of view, and c) ‘aim[s] to equip students to make disciplined and valid use of historical knowledge when analysing and evaluating present realities and future possibilities’ (p. 105). In such an approach, the teaching of history aims to transform the way students view the world (Lee, 1992; Lee, 2011; Shemilt, 2011), by helping them to understand how historical knowledge is constructed and by providing them with opportunities to build their own interpretations of the past through methods of historical inquiry (Seixas, 2000; Wineburg, 2001).

At a first glance, these two approaches seem different in the sense that while the approach advocated in the essay primarily aims to promote social aims related to the common good and historical justice, a social education approach aims primarily to the development of disciplinary understanding. However, a closer look at both approaches reveals a common goal which is to help students understand their social world and actively participate in it through a critical reading of the past and its sources. This is also evident by the fact that the social education/disciplinary approach has also been used as a means of deconstructing divisive narratives in conflict or post-conflict contexts, and to promote understanding between groups in conflict (McCully, 2012; Waldron and McCully, 2016; Perikleous, Onurkan-Samani and Onurkan-Aliusta, 2021).

Perhaps this convergence between these two approaches is more obvious in Barton and Levstik’s (2004) argument that preparing students to contribute to the effort for the common good cannot happen by teaching a fixed version of the past. On the contrary, this can only happen if ‘students take part in meaningful and relevant historical inquiries, examine a variety of evidence, consider multiple viewpoints, and develop conclusions that are defended and negotiated with others’ (Barton and Levstik, 2004, p. 260). In fact, the closing argument by Barton and Levstik in their seminal publication Teaching History for the Common Good (2004) is that preparing students for actively participating in democratic processes demands a history teaching that engages students with historical enquiries, evidential thinking, and different perspectives about the past.

A similar argument is voiced by advocates of social education approaches, who, from an opposite starting point of prioritizing disciplinary understanding over any social aims, argue that disciplinary approaches share similar values with participatory liberal democracy (Shemilt, 2011; Chapman and Perikleous, 2011). This argument is based on the idea that ‘thinking historically involves a commitment to open argument, to the public examination of evidence, and also a commitment to debate’ (Chapman and Perikleous, 2011, p. 9).

_____

Barton, K. C. and Levstik, L. S. (2004). Teaching History for the Common Good. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Chapman, A. and Perikleous (2011). Developing Historical Thinking: Theory and Research. In Chapman, A., Perikleous, L., Yakinthou, C. and Celal, R. Z., Thinking Historically about Missing Persons: A Guide for Teachers. Association for Historical Dialogue and Research.

Lee, P. J. (1992). History in Schools: Aims, Purposes and Approaches. A Reply to John White. In P. J. Lee, J. Slater, P.Walsh and J. White (Eds), The Aims of School History: The National Curriculum and Beyond. Tufnell Press.

Lee, P. J. (2011). Historical literacy and transformative history. In L. Perikleous and D. Shemilt (Eds), The Future of the Past: Why history Education Matters. Association for Historical Dialogue and Research.

McCully, A. (2012). History teaching, conflict and the legacy of the past. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 7(2), pp. 145–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197912440854

Perikleous, L., Onurkan-Samani, M., and Onurkan-Aliusta, G. (2021). Those who control the narrative control the future: The teaching of History in Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot schools. Historical Encounters, 8(2), pp. 124-139. https://doi.org/10.52289/hej8.207

Seixas, P. (2000). Schweigen! die Kinder! or, Does Postmodern History Have a Place in the Schools?. In P. Seixas, P. Streams and S. Wineburg (Eds), Teaching, Learning and Knowing History. New York University Press.

Shemilt, D. (2011). The Gods of the Copybook Headings: Why Don’t We Learn from the Past?. In L. Perikleous and D. Shemilt (Eds), The Future of the Past: Why history education matters. Association for Historical Dialogue and Research.

Simon, R.I. (2004). The Pedagogical Insistence of Public Memory. In P. Seixas (Ed.), Theorizing Historical Consciousness. Toronto Press.

Waldron, F. and McCully, A. (2016). Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland: Eroded certainties and new possibilities. In R. Guyver (Ed.), Teaching history and the changing nation state: Transnational and intranational perspectives. Bloomsbury Publishing. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474225892.ch-003

Wineburg, S. (2001). Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts. Temple University Press.