Monthly Editorial April 2021 | Einführung in den Monat April 2021

Abstract:

Landscape and identity are two interdependent factors/concepts for human self-relations insofar as they are necessarily contextualised in terms of cultural geography. This introduction to the upcoming thematic month starts from a metaphorical notion of landscape, which is related to public history as a whole; two historical examples are used to develop the issue in an exemplary way, whereupon a systematic presentation is proposed and reference is made to detailed discussions on this. In the second part, the 10 contributions of the month are presented in this context.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17839.

Languages: German, English

Das wird ein langer und vielsprachiger, vieltönender PHW-Monat; nicht nur deshalb, weil wir 5 Erscheinungswochen haben werden oder weil wir in diesem Monat weite geographische und kulturelle Strecken zu durchmessen haben, sondern vor allem auch, weil es viel aktuellen Diskussionsbedarf in der praktizierten Public History gibt.

Fragehorizonte, Praxiskonstituierung

Der Weg wird uns weit führen von einem Australier auf den Philippinen, zu einem Deutschen in Südbrasilien, dessen Spuren ein Nachfahre polnischer Einwanderer:innen untersucht, einem Ghanaer in Australien, nach Italien in die frühe Renaissance, in deutsche Lande im frühen 19. Jahrhundert, auch nach Kanada, in die Gegenwart. Dazu kommen Diskussionsbeiträge zu zwei Problemfeldern, die weltweit relevant sind, wenn wir auf den Umgang mit Geschichte in der Öffentlichkeit schauen: Gibt es akute Bedrohungen der Freiheit von historischer Forschung und Lehre und wenn: welche? Wie ist das Verhältnis von Journalismus und Geschichtswissenschaft in Zeiten der digitalen Transformation, des Aufweichens der Begrenzungen alter Rollenvorstellungen und Vertriebswege?

Dieser Monat auf PHW wird zu einem freundlich-beredsamen, vielleicht manchmal etwas zerstreut wirkenden Cicerone in der globalen Landschaft der Public History, der dies zeigt und jenes, alles natürlich für superwichtig hält, daher etwas tüttelig anmuten mag, aber doch am Ende vielleicht bei dem einen oder der anderen Leser:in eine gewisse Vorstellung vom Ganzen und der Einheit dieser globalen Landschaft der Public History entstehen lässt. Und global ist sie gewiss – nicht nur weil die Informationen, Geschichten, Deutungen, Ängste und Hoffnungen heute in nahezu Echtzeit über den Globus laufen, von Bildschirm zu Bildschirm, sondern vor allem deshalb, weil sich Selbstverständigungsprozesse unter Menschen grundsätzlich in gleichartigen interaktionellen Strukturen vollziehen, als vieldimensionale vergangenheitsbezogene Identitätsdiskurse. Wohin man auch blickt mit entsprechenden Fragen, an welchen Ort, in welche Zeit in dieser fragekonstituierten dreidimensionalen epistemischen Landschaft: man findet Public History. Dieser Fragehorizont konstituiert eine wissenschaftliche Praxis, er bestimmt auch das Koordinatensystem einer normativen Pragmatik in ihr. Insofern ist das Monatsthema zugleich auch ein Thema der ganzen Zeitschrift. 10 Beiträge von 12 Autor:innen aus 7 Ländern in 5 Sprachen — mit 11 OPR-Reflexionen und hoffentlich vielen weiteren Kommentaren ergeben ein kaleidoskopartiges Muster der Regelmäßigkeit aus Spiegelungen.

Aber dieses Thema “Landschaft und Identität” kann natürlich und soll auch näher bestimmt werden.

Von Bacoli nach Comiso

Was ist das eine, die “Landschaft”, was das andere, die “Identität”, in welchem Verhältnis stehen sie? Vielleicht ist es gut, diesen genaueren Bestimmungen zunächst anhand einiger womöglich weniger bekannter Fälle nachzugehen.

Abb. 1: Golfo di Napoli con Castellammare di Stabia e Vesuvio by Edmund Berninger

Im Konsulatsjahr des Gaius Vipstanus und C. Fonteius, die sich, beide sonst nicht weiter auffällig geworden, wahrscheinlich damals auch nicht hätten träumen lassen, fast 2000 Jahre später bei Public History Weekly zitiert zu werden, in diesem Konsulatsjahr also (“59 nach Christus” – also fünf Jahre vor den grausamen Christenverfolgungen in Rom, wodurch die Datierungsart also auch etwas späte Gerechtigkeit herstellt) … nun, in diesem Jahr beschloss der Princeps Germanicus seine Mutter ums Leben zu bringen, oder genauer: umbringen zu lassen, die sagenhafte Agrippina. Der Princeps besaß bis dahin kein ganz schlechtes Ansehen, diese Mordtat war allerdings unerhört und musste möglichst im Verborgenen geschehen.[1]

Nero, wie man ihn besser nennt, lud seine Mutter in eine kaiserliche Villa ein, zum Fest der Quinquatern. Diese Villa befand sich im heutigen Bacoli, am Golf von Neapel. Übergehen wir die grausamen Ereignisse, die sich dann an einer kleiner Nebenbucht, dem Lucriner See, nicht weit von Puteoli, ereigneten. Jedenfalls: der Princeps und sein Hof hielten sich dort gern auf, weil sie es schön und angenehm fanden. Der Zusammenklang von kühlender Meeresbrise, der durch den Vesuv und den Monte Nuovo und die optische Schichtung von Meer und Land konturierte Horizont, das vegetationsfreundliche Klima, dieses besondere Aroma in der Luft, die gute Verkehrsverbindung nach Rom zu den Geschäften, nach Napoli zu den Vergnügungen — all das komponierte sich für die Betrachter:innen zu einem einheitlichen Gesamtbild, das im anstrengenden Rom zur tröstenden Vision werden konnte, ja sogar musste.

Jeder Aufenthalt dort und jede Rückkehr nach Rom verstärkte die Kraft dieser Vorstellung mehr. Für den Princeps aber wurde im Jahre 59 dieses Gesamtbild geographischer Eindrücke, gerahmt durch die familiäre Tradierung von Erholungserfahrungen über Generationen, auf einen Schlag, wenn man auch in diesem Zusammenhang so sagen will, völlig umcodiert. Alles war wie immer, die sanfte Brandung plätscherte, der Mond streichelte mit seinem kalten Licht die Konturen, für Nero hatte diese Landschaft aber ihre Semantik verkehrt, und er suchte die nahe Stadt, bedurfte dringend des Landschaftswechsels, floh, was er so lange gesucht hatte:

“… quia tamen non, ut hominum vultus, ita locorum facies mutantur, obversabaturque maris illius et litorum gravis adspectus (et erant qui crederent sonitum tubae collibus circum editis planctusque tumulo matris audiri), Neapolim concessit…” [2]

Die Hand an die eigene Mutter legen zu lassen, so ruchlos diese selbst gewesen sein mag, dieser Anschlag auf die eigene biologische und biographische Herkunft, war ebenso in geographische Bedingungen eingebettet wie das Bukolische zuvor. Die Berge selbst wurden zu Zeugen dieser Abtrennung, in ihrer psychologischen Repräsentation. Für Nero war das geliebte Refugium zu einer Landschaft der Furien geworden.

Abb. 2: Strade Ferrate della Sicilia – Tronco Modica – Comiso by Biblioteca comunale Palermo

Nicht sehr weit von diesen Geschehnissen und auch schon im 20. Jahrhundert, aber noch zu einer Zeit, da das Leben mit seiner Arbeit, seiner Liebe und seinem Leid sein Antlitz noch nicht sehr stark verändert hatte im Vergleich zur Zeit Burros, des mörderischen Handlangers des Princeps, da gab es einen Lehrer mit hagerem Gesicht unter dicken Brillengläsern, einen Provinzphilologen, in einer kleinen Stadt, der in seiner eigenen Lebensspanne, bei lebendigem Leibe faktisch, erfuhr, wie sich dann plötzlich doch alles änderte, in einer mediterranen Landschaft, in Meeresluft, unter Olivenbäumen; eine kleine vergessene Stadt auf zwei Felsenstufen, südlicher als Tunis, aber 10 Kilometer noch von der Küste.

Und für ihn, Gesualdo Bufalino, wurde es zu einer Lebensaufgabe, diesen einschneidenden Wandel von Lebenswelt als Raum, von Landschaft, als Inbegriff des geographisch-kulturell verankerten Selbstverständnisses von Menschen in Gruppen, herausgefordert noch durch einen strategisch wichtigen NATO-Nuklearwaffen-Stützpunkt im Kalten Krieg, minutiös zu dokumentieren. Dabei machte er eine wichtige Entdeckung:

“Poiché storia non è solo quella conservata negli annali del sangue e della forza; bensì quella legata al luogo, all’ambiente fisico e umano in cui ciascuno di noi è stato educato. Storia è il gesto con cui s’intride il pane nella madia o si falcia il grano; storia è un nomignolo fulmineo, un proverbio cattivante, l’inflessione di una voce, la sagoma di una tegola, il ritornello di una canzone; tutto ciò, infine, che reca lo stemma del lavoro e della fantasia dell’uomo. Materia che deperisce prima d’ogni altra e di cui nessuno, quasi, si cura di custodire i reperti.”[3]

“Geschichte” steht, diese kleine Anmerkung muss sich Freund Bufalino gefallen lassen, hier etwas im schiefen Gegensatz zu den Annalen, wie an Tacitus gerade zuvor gezeigt gezeigt worden ist. “Geschichte” wie sie aber Bufalino kollektividentifikatorisch für relevant hält, sei es nun in Abgrenzung oder in Affirmation, ist eingebettet, kontextualisiert, in kulturgeographische Verhältnisse. Dialekte, die sich in Tälern ausprägen, Teig, der sich nur kneten lässt, wo Getreide zur Verfügung steht, Lieder der Arbeit und des Erholens, die gegen die Nachbargemeinde in Spottversen geformt sind.

Bufalino jedenfalls hat sich des Schrittes ins viel gepriesene Offene der industriellen Moderne, der Auflösung der Besonderheiten so weit als möglich entzogen (die er durch den Krieg kennenlernen musste), der Absolutismus der Wirklichkeit, wie ihn Blumenberg begriff,[4] war für ihn kein Schrecken per se, das macht ihn zum Philosophen, zugleich begriff er auch in seiner Landschaft, wir wollen es eine “Heimat” nennen, die Auflösung der althergebrachten Orientierungsordnung und das Rückverwiesensein auf individuelle Daseinserarbeitung als Zeitzeugenschaft seines Lebens.

“Heimat”, dieser Begriff, der einer der sprachhistorisch industriellen Moderne und der menschlichen Selbstermächtigung ist, fasst diese Zeitzeugenschaft landschaftlicher Umcodierung und (touristisch und infrastruktur-ökonomisch getriebener) Standardisierung kulturgeographischer Erfahrungswelten an der Wurzel. Denn es wird dem statistisch ermittelbaren Normalmenschen zum Genusse (auch dem Autor), wenn er in bequem zugerichtete bildhafte Kataloglandschaften hintransportiert werden kann. Die auf Verwertbarkeit ausgerichtete Zurichtung des Eigenen, des persönlichen Nahraums muss dagegen als Verletzung von immateriellem Eigentum erscheinen, zuweilen auch durchaus des materiellen. Massentourismus und Boom der Bürger:inneninitiativen zur Abwehr von irgendwas gehen Hand in Hand.

Der Umstand, das solche “Heimat” anders als von zu Meisterdenkern verklärten Autoren wie Ernst Jünger nicht ohne Weiteres essentialistisch zu denken ist,[5] sondern sich als Schöpfung, als Produkt kognitiver Arbeit verstehen lässt, dass man sich etwas zur “Heimat” machen kann, oft machen muss, und dass wir alle, die wir durch die Umstände unsere Wohnorte wechseln mussten, inzwischen lernen konnten, wie das auch geht, das ist eine Einsicht, die zuletzt immer mal wieder formuliert worden ist. Kulturgeographisch kontextualisierte Selbstverhältnisse sind gestaltbar, das konnten wir schon von Tacitus lernen.

Man muss Rudolf Borchardts, des Gärtners und Redners, verquer idealistische Deutschheitsliebe nicht teilen, wenn man diesen ins Kulturanthropologische gewendeten Gedanken auch bei ihm zu finden vermag.

“Der Deutsche ist überall zu Haus und nicht zu Haus, ist zu Haus, wo er eben steht. Die Welt geht in ihn ein, indes er in der Welt aufgeht. Er ist der alte Wanderer seiner Geschichte, der Gast auf Erden.”[6]

Der Deutsche, den hier Borchardt beschreibt, das ist der kulturgeographisch erwachte Mensch, der Tacitus und Bufalino, die Public Historians aller Zeiten.

Identitäts-Raum-Beziehungen

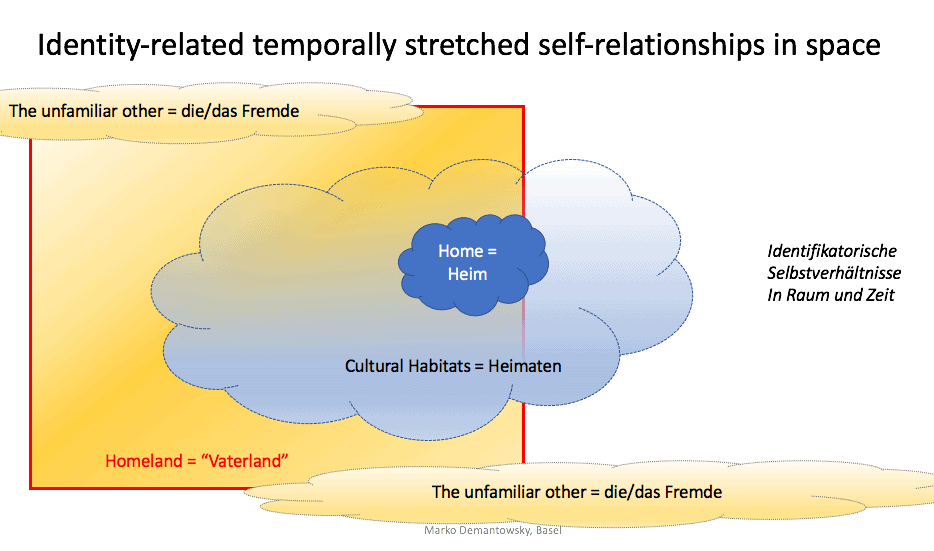

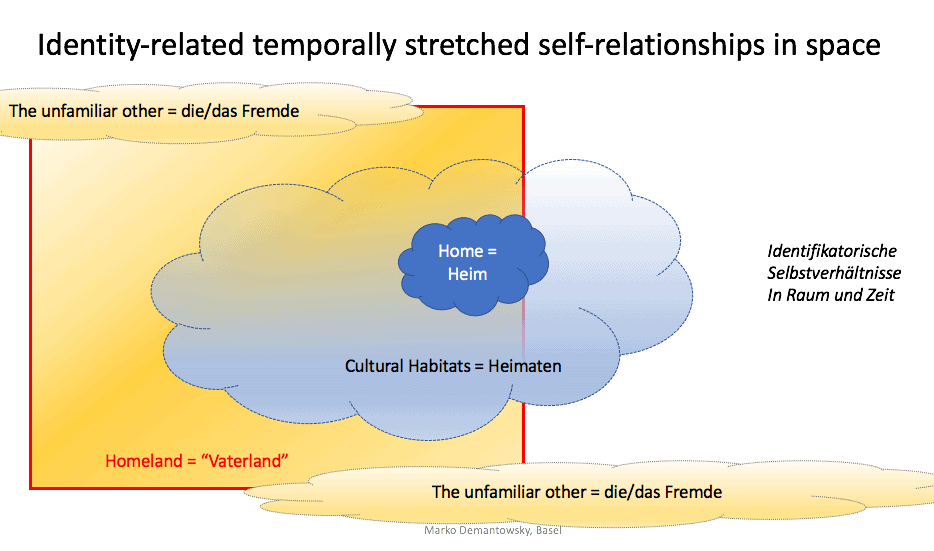

Diese menschlichen und anthropologisch verankerten Identitäts-Raum-Beziehungen lassen sich versinnbildlichen. Es handelt sich um zeitlich gestreckte Selbstverhältnisse im Räumen, transponierbar je nach Position des Individuums. Landschaft findet hier als Habitat/Heimat seinen Platz, insofern es für den Wahrnehmenden zu einem multipel erschlossenen Ort geworden ist. Heimatgefühle manifestieren sich in ihrer Realisierung als Wiedererkennen, als Eingefügtsein, Verlassensein der Fremde und in ihrer Nichtrealisierung als Sehnsucht danach, als Verlust und Defizit. Weder das eine noch das andere ist auf Kindheitsorte beschränkt.

Abb. 3

Heimat als Bewusstsein und Bewusstseinszustand, so die These, lässt sich als ein zeitlich gestrecktes Selbstverhältnis im Raum, als ein Habitat verstehen, als maximales Territorium intuitiver Orientierbarkeit und Orientierung. Eine ausführliche Erläuterung und Diskussion dazu wird sehr bald nachzulesen sein.[7] Heimat ist das psychische Pendant zur vertrauten Kulturgeographie, zur Landschaft.

Die raumbezogene Identität hat also sehr viel mehr Dimensionen als nur die nationale. Landschaftlich bezogene Selbstvergewisserung ist sogar geradezu antinational, weil in der Regel kleinräumig und immer per definitionem sinnlich erfahrbar. Stärkung solchen landschaftlichen Bewusstseins ist auch ein gutes Antidot gegen die Irrwege nationaler Imaginationen, wie sie von Arno Borst so tiefenscharf auseinandergelegt worden sind.[8] Das Landschaftliche ist älter, und ich hätte hier noch viele andere Beispiele nennen können. Seine industrielle Zurichtung bis hin zum Trachtenwesen und dem Mordsgaudiallodri der technisierten Bergskiindustriesse ist ein historischer Zwilling der weltvernichtenden Allesverkonsumierung.

Dabei wird hier keiner Gesamtmusealisierung und Staubfängerei das Wort geredet, sondern der Bereitschaft, die identifikatorische Aufladung der eigenen landschaftlichen Kontexte zu reflektieren, sie selbst neu zu entdecken, sie von anderen entdecken zu lassen, sich der Komplexität des Eigenen und Fremden und seiner mannigfachen Transformationen bewusst zu machen. Landschaft ist Geographie im Wandel[9] – und wir mit ihr – jede:r für sich, wir mit anderen.

Die Beiträge der Aprilausgabe

Den Auftakt in den Themenmonat macht Robert Parkes (Newcastle, NSW), der uns mit seinem Text über Capoeira and Eskrima sofort mitten hinein führt in die komplexen Zusammenhänge von Landschaft und Identität. In seinem Text wird das auf mehrfache Weise deutlich: in den topographischen Verankerungen des Itinerars dieser vielfachen kulturellen Aneignungen, in den verstreuten Übergabe- und Übernahmeprozessen, im vielfachen Wandel der Begrifflichkeiten und ihrer Sinnstiftungen, in der Selbstreflexivität des Historiographen und Praktikers, der mit uns, seinen Leser:innen, eingebunden ist in die umstürzende Transformation des westlichen Denkens im Horizont postkolonialer Einsichten und schliesslich in der Körperlichkeit der beschriebenen Kulturanveranwandlungen, deutlich machend, dass auch in unseren körperlichen Routinen und Leistungsgrenzen Landschaften identitätsstiftender Bewegungen eingeschrieben sind.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17815

Der zweite Autor im Themenschwerpunkt, Stéphane Lévesque (Ottawa, Canada), unternimmt ein Projekt der Begriffsarbeit, wir bringen diesen Text in der zweiten Woche, um zur terminologischen Selbstvergewisserung einzuladen, bevor wir unsere anschaulichen Wanderungen durch Weltlandschaften der Public History wieder aufnehmen. Im Zentrum des Interesses dieses Autors steht der Begriff der Identität, ihnen besorgen die jüngeren politischen Tendenzen überall. Den Ausgangspunkt sucht er bei der Unterscheidung der Typen des “Geschichtsbewusstseins” und der “Fachwissenschaft [disciplinary history]. Aus dieser Typologisierung entwickelt XY eine Anregung für die gegenwärtige historische Bildung, die notwendigerweise mit ihren politischen Rahmenumständen korrespondieren muss.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17821

In der dritten April-Erscheinungswoche von PHW begegnet den Leser:innen ein Text von Michel Kobelinski (Curitiba, Brasilien), er stellt uns einen am Anfang des 2. Jahrhunderts nach Paraná ausgewanderten deutschen Maler vor und beginnt mit der überraschenden Frage, ob der Düsseldorfer Hans Schiefelbein tatsächlich brasilianische Kunst und kulturelle Identität zu erzeugen vermochte? Für diese Frage braucht es eine Vorstellung der spezifischen südbrasilianischen Landschaft, ihrem Ausmass, ihrer Gestaltung, ihrer Bevölkerung und der künstlerischen Repräsentation dieser Merkmale in Schiefelbeins Bildern. An dem Tatbestand, dass Schiefelbein und v.a. dessen Bilder heute in Paraná zu den relevanten Identitätsmarkern gehören, lassen jedenfalls XYs Informationen keinen Zweifel. Wie gelingt es also, solche Identitätsmarker zur Anerkennung zu bringen? Der Bezug auf typische geographische und kulturelle Landschaftselemente der Referenzregion scheint dabei eine Erfolgsstrategie zu sein.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17822

Wir kommen – Woche 4 – zu einem Beitrag von Claudia Gatzka (Freiburg/Br., Deutschland) mit einer starken, forschungsbasierten These zum Rahmenthema. Die These lautet in aller nötigen Verkürzung: Die identifikatorische Aufladung von “Landschaft”, der Begriff in heutiger Bedeutung überhaupt sei eine Erfindung der frühen Tourismuswirtschaft, ja: Tourismuswirtschaft und emphatischer Landschaftsbegriff seien eine Art Zwillingsgeburt. Landschaft wurde zur Landschaft, als sie als solche verkauft worden ist. Tourismus wurde identitätsbildend mit Landschaftsbezug als sich ein romantisches Bewusstsein monetarisierte. Die Autorin verweist (in deutschen Bezügen) auf das Rheinland.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17823

Abb. 4: Gruben. Le Weisshorn (4506 m) vu depuis le chemin du col de Forcletta

Einer südlicheren Landschaft, wenn man aus dem Rheinland den alten Handelswegen über den Alpenkamm und die Apenninen folgt, auf einer Route, die so viele Heere, Händler und Heloten genommen haben, auf den Geleisen römischer Wegebauer, wendet sich unsere Autorin Roberta Biasillo in der fünften Publikation unseres Themenschwerpunkts zu: der Toskana oder genauer dem Val d’Orcia. Sie verfolgt vom Spätmittelalter bis in die Gegenwart ebenfalls die Erfindungsverfahren oder besser gesagt die Stiftungsanlässe einer Landschaft. Dieser Prozess wird allerdings von Tourist:innen schon als abgeschlossen erlebt und natürlich in dieser Rahmung tradiert und gleichsam verewigt, als ob Landschaften keine Zeiten hätten. XY zeigt uns, wie ein Zusammenwirken von Politik, Repräsentation, Kunst und nicht zuletzt wirtschaftlicher Ratio zu einem identitätsstiftenden geographischen Gesamteindruck führt, der gar nicht anders denn als Landschaft begriffen werden kann.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17824

Diese fünf Beiträge mit ihren OPR nahmhafter Wissenschaftler:innen unterschiedlicher Disziplinen bilden das thematische Hauptprogramm. Aber auch ein weiterer Beitrag hätte ohne Mühe in dieses Hauptprogramm eingefügt werden können, bildet aber eine Brücke in das freie Parallelprogramm, die Speakers’-Corner-Sparte des April, das sich mit einem metaphorischen Landschaftsbegriff als Vermessung einer Topos-Graphie der gegenwärtigen Public History begreifen lässt.

Im Speakers’-Corner-Ressort der Woche 4 führt uns Gideon Boadu nach Ghana, also weiter nach Süden, Richtung Äquator, Kurs Südsüdwest vom Val d’Orcia aus, mehr als 6000 Kilometer. Wie leicht vergisst man, wie groß Afrika ist und wie nahe Italien an Afrika liegt, gleichwohl. Der Autor lässt uns teilhaben an den wichtigen Aspekten der ghanaischen Geschichtskultur, er bezieht diese Aspekte erklärend aufeinander, systematisch wie historisch und beides in seiner geographischen Bedingtheit und postkolonialen Situativität. Die Redaktion ist dankbar für diesen wichtigen Einblick und hofft, einen Beitrag dafür zu leisten, diese Landschaft der Public History ihrer oder besser: unserer falschen Fremdheit zu entkleiden. Der Beitrag wird begleitet von einem OPR aus Ghana, auch darauf freuen wir uns.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-18122

Zurück in den globalen Westen und seine Public History, die Privilegiertheit seiner Probleme, die seine Bewohner:innen oftmals in Aufregungsspiralen treiben, als gäbe es kein Morgen, als sei das Ihre gerade jetzt weltbewegend. Public History Weekly ist als intellektuelle Ausnüchterungszelle angelegt, Konflikte im öffentlichen Umgang mit Geschichte sollen hier nicht vorangetrieben, sondern begriffen werden. Dass solche Kühle unter Konfliktparteien nicht immer willkommen ist, kann nicht anders sein. Public History Weekly ist auch eine Plattform, solche Konflikte zivilisiert und mit redaktionellem Filter auszutragen. Jede:r ist zur Beteiligung mit einem Kommentar eingeladen (Guidelines).

Schon in der zweiten Aprilwoche erscheint ein Diskussionsbeitrag dreier Historiker:innen, Christoph Dartmann, Antje Flüchter und Silke Schwandt, zu einer Debatte, die von einem öffentlichen Aufruf und Unterschriftensammlung ausgelöst worden ist und zur Gründung eines “Netzwerks” führte. Zentraler inhaltlicher Kernpunkt ist offenbar, sich “allen Bestrebungen” widersetzen zu wollen, “die Freiheit von Forschung und Lehre aus ideologischen Motiven” einschränken.[10] Die Argumentation, die diesen Aufruf begründet, nehmen sich die drei Historiker:innen aus der Perspektive ihrer Wissenschaft vor, etwas eingehender zu prüfen. Der Aufruf richtet sich nicht speziell an die Geschichtswissenschaft, aber es haben sich vergleichsweise viel Historiker:innen daran beteiligt. Der Aufruf nimmt auf analoge Konflikte in den USA, UK oder andernorts Bezug, er ist insofern Ausdruck einer internationalen Diskurssituation und insofern gewiss interessant für Public Historians weltweit.

Weil das Thema nun tatsächlich innerhalb der Geschichtswissenschaft strittig ist, haben wir für diesen Fall zwei OPR eingeladen und sind froh zwei namhafte Kolleg:innen dafür gewonnen zu haben.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17995

Damit kommen wir zu einem weiteren heißen Thema gegenwärtiger Public History, diesmal noch spezieller für Deutschland, aber gewiss ebenso von weltweiter Relevanz. Es geht um das Verhältnis von Geschichtswissenschaft und Geschichtsjournalismus und seine Entwicklung, gekennzeichnet durch die digitale Transformation, die einerseits die Skalierung von Information und Meinung auch außerhalb der altetablierten Feuilletonseiten der grossen überregionalen Qualitätszeitungen möglich macht (über digitale Rezensionsplattformen z.B., aber auch über ein Open-Access-Journal wie Public History Weekly), die andererseits aber auch dazu führt, dass die alten Feuilletonformate über ihre Social-Media-Extensionen sich den Dynamiken digitaler Informations- und Meinungsskalierungschancen zu ergeben nicht immer abgeneigt sind.

Wir bringen zu diesem Themenkomplex gleich zwei Beiträge aus aktuellerem Anlass, mit dem für PHW angesichts von Redaktionsplanung, Redaktion und Übersetzung notwendigen gewissen Zeitverzug, einem spezifischen “time lag”, das sowohl bei bei Autor:innen als auch beim Publikum für heilsame Distanz sorgt und Public History Weekly zu einem Reflexionsorgan mittlerer Geschwindigkeit macht. Die beiden Beiträge, einmal von Gabriele Metzler (HU Berlin) (1) und einmal von den Sonja Dolinsek und Claudia Gatzka (2), diskutieren das bedeutsame Thema des Verhältnisses von Geschichtswissenschaft und Geschichtsjournalismus von unterschiedlicher institutioneller Warte, die beiden damit korrespondierenden OPR verstärken diese Diversität.

(1) DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-18061

(2) DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-18178

_____________________

Literaturempfehlungen

- Küster, Hansjörg. 2012. Die Entdeckung der Landschaft: Einführung in eine neue Wissenschaft. Originalausgabe. Beck’sche Reihe 6061. München: Verlag C.H. Beck.

- Ritter, Joachim. 1974. Subjektivität. Sechs Aufsätze. 1st ed. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

- Schama, Simon. 1995. Landscape and Memory. 1st ed. New York: A.A. Knopf : Distributed by Random House.

_____________________

[1] Siehe zu den ganzen Geschehnissen: Tacitus, Cornelius. 2018. Annalen: deutsche Gesamtausgabe, XIV. Herausgegeben von Werner Suerbaum. Übersetzt von August Horneffer. Stuttgart: Kröner.

[2] Ibid., XIV, 10.

“Weil aber eine Landschaft nicht ihr Antlitz wechselt wie ein Mensch, und weil er immer den beängstigenden Anblick jenes Meeres und Strandes vor Augen hatte – manche Leute glaubten sogar, man höre von den Bergen her Trompetenklänge und vom Grab der Mutter her Wehrufe -, ging er nach Neapel.” (übersetzt von August Horneffer)

[3] Bufalino, Gesualdo. 2001. Museum der Schatten: Geschichten aus dem alten Sizilien, 15. Übersetzt von Maja Pflug. 5.-6. Tsd. Salto 33. Berlin: Wagenbach.

“Denn Geschichte ist nicht nur die der Annalen, die mit Feuer und Schwert geschrieben werden, sondern auch die an den Ort, die physische und menschliche Umwelt, in der jeder von uns erzogen wurde, gebundene. Geschichte ist die Geste, mit der Brotteig im Backtrog geknetet wird oder das Korn gemäht wird; Geschichte ist ein jäh auftauchender Spitzname, ein passendes Sprichwort, der Tonfall einer Stimme, die Form eines Ziegels, der Refrain eines Liedes; all das schließlich, was von der Arbeit und der Phantasie des Menschen geprägt ist. Dinge, die vor allen anderen vergehen und deren Überreste zu bewahren – fast – niemand sich sorgt.”

[4] Blumenberg, Hans. 1979. Arbeit am Mythos, 9–39. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

[5] Jünger, Ernst. 2017. Der Waldgang. Herausgegeben von Detlev Schöttker. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta.

[6] Rudolf Borchardt. 2018. Der Deutsche in der Landschaft (1927), 496. Berlin: Matthes & Seitz.

[7] Das Schema und diese Überlegungen stammen aus Marko Demantowsky.”The public history of heimat and the schools”. In: Conflicts in history education in Europe. Political context, history teaching and national identity. Information Age Publishing (IAP), Charlotte NC 2021 (eds. by Ander Delgado, Andy Mycock) [in print].

Eine teilidentische deutsche Fassung als “Was soll das bloss mit dieser „Heimat“?” In: Geschichtsbewusstsein in der Gesellschaft. Festschrift für Bernd Schönemann. Wochenschau, Schwalbach/Ts. 2021 (hrsg. von Jan M. Hoffrogge et al.), S. 170-188.

[8] Borst, Arno. 1979. „Barbarossa Erwachen – Zur Geschichte der deutschen Identität.“ In Identität, herausgegeben von Odo Marquard und Karlheinz Stierle, 8:17–60. Poetik und Hermeneutik. München: W. Fink.

[9] Küster, Hansjörg. 2013. Geschichte der Landschaft in Mitteleuropa: von der Eiszeit bis zur Gegenwart, 388-393. Jub.-Ed. München: Beck.

[10] „Manifest“. 2021. Netzwerk Wissenschaftsfreiheit (blog). Februar 2021. https://www.netzwerk-wissenschaftsfreiheit.de/.

_____________________

Abbildungsnachweise

Beitragsbild: Winters bosgezicht by Eugène-Joseph Verboeckhoven (1863), Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, arranged by (c) Moritz Hoffmann 2021.

Abb. 1: Golfo di Napoli con Castellammare di Stabia e Vesuvio. Luogo di esposizione sconosciuto by Edmund Berninger (1843-1909) – Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23191054

Abb. 2: Strade Ferrate della Sicilia – Tronco Modica – Comiso by Biblioteca comunale Palermo via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Abb. 3: Scheme of identity-related temporally stretched self-relationships in space (c) Marko Demantowsky 2020.

Abb. 4: Gruben. Le Weisshorn (4506 m) vu depuis le chemin du col de Forcletta by Guillaume Baviere via Flickr (CC BY 2.0).

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Demantowsky, Marko: Landscape and Identity. In: Public History Weekly 9 (2021) 3, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17839.

Redaktionelle Verantwortung

This is going to be a long and multi-lingual, multi-sounding PHW month; not only because we have 5 publication weeks or because we be traversing vast geographical and cultural distances, but foremost because currently practised public history provides much food for thought and discussion.

Horizons of Questioning, Foundations of Practice

Our journey will take us far – from an Australian in the Philippines, to a German in southern Brazil whose traces are being investigated by a descendant of Polish immigrants, to a Ghanaian in Australia, to the early Renaissance in Italy, to German lands in the early 19th century, and also to Canada and to the present. We also have contributions on two globally relevant issues regarding how history is dealt with in the public sphere: Is the freedom of historical research and teaching under acute threat, and if so, which threats are these? What is the relationship between journalism and historical scholarship in times of digital transformation, when the boundaries of previous role concepts and distribution channels are dissolving?

Our April edition will be a friendly and eloquent, perhaps even a somewhat absent-minded cicerone in the global landscape of public history, a guide who shows us this and that, who of course considers everything to be ultra- important, and who therefore may seem a little shaky. Still, our attendant might conjure up some sense of the whole and of the unity of this global landscape of public history in one or the other reader. And it is certainly global — not only because information, stories, interpretations, fears and hopes are shuttling and scuttling across the globe almost in real time, from screen to screen, but most of all because essentially we understand ourselves in similar interactional structures, in multi-dimensional identity discourses related to the past. Wherever we look — regardless of inquiry, locale and time in this three-dimensional epistemic landscape constituted by questions — we find public history. This horizon constitutes an academic discipline, and this horizon also determines the coordinate system of normatively guided action in contexts of public history. This month’s theme is thus also one of the themes of our journal. Ten contributions by 12 authors from 7 countries in 5 languages — with 11 OPR reflections and hopefully many more comments — create a kaleidoscopic pattern of regular reflection.

And yet, the theme of our early spring edition — “Landscape and identity” — can of course and also needs to be fleshed out in more detail.

From Bacoli to Comiso

What is “landscape,” what “identity”? How are they related? It might help if we first explore these designations aided by some perhaps lesser-known cases.

fig. 1: Golfo di Napoli con Castellammare di Stabia e Vesuvio by Edmund Berninger

In the year when Gaius Vipstanus and C. Fonteius, two otherwise inconspicuous fellows, served as consul, they most likely would not have dreamed of being cited in Public History Weekly almost 2000 years later. In the year of their consulship (“59 AD,” i.e. five years before the cruel persecutions of the Christians began in Rome, so that this kind of dating method establishes some late justice) … Germanicus resolved to kill his mother, the legendary Agrippina, or rather to have her killed. The Princeps was not ill-reputed, at least not until then. Yet this murderous act was unheard of and had to be committed as secretly as possible.[1]

Nero, as he is better known, invited his mother to an imperial villa, to the feast of Quinquatrus. This villa was located in what is now Bacoli, a town in the Gulf of Naples. Let’s pass over the cruel events that occurred in a small bay, Lake Lucrine, not far from the town of Puteoli. In any case, the princeps and his court liked to sojourn there because they found the place beautiful and pleasant. The consonance of the cooling sea breeze, the horizon contoured by Vesuvius and Monte Nuovo and the optical layering of sea and land, the friendly climate, that special scent of the air, the good connections to Rome for business, to Naples for pleasure — all of this composed itself for the viewer into a unified picture that could, indeed had to, become a comforting vision in the exhausting hustle and bustle of Rome.

Every stay there and every return to Rome buttressed this idea. For the Princeps, however, in the year 59 this overall picture — of geographical impressions, framed by the family tradition of recreational experiences over generations — became completely recoded all at once, to put matters that way. Everything was as usual: gentle waves lapped the shore and the moon caressed the landscape with its cold light. But for Nero, this landscape had reversed its semantics, and he sought the company of the nearby city, urgently needing a change of scenery, fleeing what he had sought for so long:

“… quia tamen non, ut hominum vultus, ita locorum facies mutantur, obversabaturque maris illius et litorum gravis adspectus (et erant qui crederent sonitum tubae collibus circum editis planctusque tumulo matris audiri), Neapolim concessit…”[2]

To lay one’s hands on one’s mother, however nefarious she may have been, this assault on one’s own biological and biographical origins, was as embedded in geographical conditions as the bucolic scenery had been previously. The mountains, in their psychological representation, witnessed this separation. For Nero, it had become a landscape of the Furies, the female deities of vengeance.

fig. 2: Strade Ferrate della Sicilia – Tronco Modica – Comiso by Biblioteca comunale Palermo

Not far removed from these events and in space but in the 20th century, but still at a time when life with its work, love and suffering had not yet changed its face very much compared to the time of Burro, the princep’s murderous henchman, there lived a teacher with a gaunt face concealed behind thick glasses, a provincial philologist, in a small town. He experienced first-hand, during his lifetime, how all of sudden everything changed, in a Mediterranean landscape, in the sea air, beneath olive trees; a small forgotten town sitting atop two undercliffs, farther south than Tunis, but still 10 kilometres from the coast.

For this man, Gesualdo Bufalino, his life’s work became to meticulously document this drastic change of the lifeworld as space, of landscape as epitomising self-image, how people living in communities saw themselves as rooted in local geography and culture, only to be challenged by a strategically important NATO nuclear weapons base during the Cold War. In the process, he made an important discovery:

“Poiché storia non è solo quella conservata negli annali del sangue e della forza; bensì quella legata al luogo, all’ambiente fisico e umano in cui ciascuno di noi è stato educato. Storia è il gesto con cui s’intride il pane nella madia o si falcia il grano; storia è un nomignolo fulmineo, un proverbio cattivante, l’inflessione di una voce, la sagoma di una tegola, il ritornello di una canzone; tutto ciò, infine, che reca lo stemma del lavoro e della fantasia dell’uomo. Materia che deperisce prima d’ogni altra e di cui nessuno, quasi, si cura di custodire i reperti.”[3]

“History,” and our friend Bufalino must take this aside on the chin, is opposed somewhat mistakenly to the annals here, as Tacitus has just shown us. But “history,” which Bufalino considers relevant to collective identification, whether in distinction or affirmation, is embedded and contextualised in cultural-geographical relations. Dialects that form in valleys, dough that can be kneaded only where grain is available, songs of work and recreation cast in mocking verse against the neighbouring community.

Bufalino, at any rate, avoided as best he could the much-vaunted openness of industrial modernity, the dissolution of particularities (imposed upon him by war), the absolutism of reality, as Blumenberg called it,[4] did not scare him per se, which makes him a philosopher. At the same time, he also understood in his landscape, let’s call it “heimat,” the dissolution of the traditional order of orientation and being referred back to the individual coming to terms with existence as a contemporary witness of (his own) life.

“Heimat”: The word belongs to the language and history of industrial modernity and human self-empowerment. It strikes at the root of this contemporary testimony to the recoding of landscape and to the standardisation of cultural-geographical worlds of experience (driven by tourism, infrastructure and economic rationale). For the statistically ascertainable normal person (including the author) enjoys being transported into comfortably dressed up picturesque landscape found in brochures and catalogues. On the other hand, the tailoring of what we consider ours to the principles of usability and exploitability must strike us as a violation of immaterial property, sometimes even of material property. Mass tourism and the boom of citizens’ initiatives to defend something go hand in hand.

Now Heimat it seems to me – but not to authors like Ernst Jünger, who have been transfigured as master thinkers – cannot simply be thought of in essentialist terms.[5] It can, however, be understood as a creation, as a product of cognitive work. We can, and often we must, make something our “heimat.” All of us whom circumstances have had forced to move home, had to learn how to accomplish this. This insight has recently been formulated time and again. As Tacitus teaches us, cultural and geographical contexts shape our relation with ourselves.

We needn’t share Rudolf Borchardt’s, the gardener and orator’s, quirky, idealistic love of Germanness when he, too, articulates this idea, by leaning towards cultural anthropology:

“Der Deutsche ist überall zu Haus und nicht zu Haus, ist zu Haus, wo er eben steht. Die Welt geht in ihn ein, indes er in der Welt aufgeht. Er ist der alte Wanderer seiner Geschichte, der Gast auf Erden.”[6]

Borchardt’s German is the culturally and geographically awakened person, the Tacitus and Bufalino, the public historians of all times.

Identity-space Relations

We can visualise these human and anthropologically rooted relations between identity and space. These relations with ourselves in space stretch out in time, they are transposable depending on the individual’s position. Landscape finds its place as habitat/heimat, insofar as it has opened up in manifold ways to those perceiving it. If realised, feelings of heimat manifest as recognition, as feeling included, as abandoned foreign lands; if unrealised, they manifest as yearning, as loss and deficit. Neither the one nor the other is limited to childhood places.

fig. 3

We can understand heimat as consciousness and as a state of consciousness, as a relation with ourselves in space that stretches out in time, as a habitat, as a maximum territory of intuitive orientability and orientation. I have discussed this elsewhere in more detail.[7] Home is the psychic counterpart to a familiar cultural geography, to landscape.

Space-related or place-based identity thus has many more dimensions than merely the nation. Landscape-related self-assurance is even downright anti-national, as it is usually small-scale and by definition always lends itself to sensory experience. Strengthening such an awareness of landscape is also a good antidote to the aberrations of national imaginaries, as so profoundly dissected by Arno Borst.[8] Landscape is older, and I could cite many other examples. Its industrial adaptation up to the traditional costumes and the hullaboloo of the mechanised mountain ski industry is a historical twin of the world-destroying consumption of everything.

I’m not making the case for total museumisation and dust trapping, but for the willingness to reflect on the identificatory charging of our own landscapes, to rediscover these (for) ourselves, to let others discover them, to become aware of the complexity of the familiar and the unfamiliar and its manifold transformations. Landscape is geography in flux [9] — as we are too — all of us on our own, and each of us with everyone else.

The Contributions to the April Issue

Our thematic month opens with Robert Parkes (Newcastle, NSW), whose contribution on capoeira and eskrima immediately leads us into the complex connections between landscape and identity. He shows us this various ways: in the topographical anchoring of the itinerary of these multiple cultural appropriations; in the scattered processes of transfer and adoption; in the multiple changes in terminology and their production of meaning; in the self-reflexivity of the historiographer and practitioner, who is involved with us, his readers, in the large-scale, relentless transformation of Western thinking in the horizon of postcolonial insights; and finally in the corporeality of the described cultural adaptations. These reveal that landscapes of identity-forming movements are also inscribed in our bodily routines and limits of performance.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17815

Our second author, Stéphane Lévesque (Ottawa, Canada), will be presenting a conceptual paper, to be published in the second week. He invites terminological reflection before we resume our descriptive wanderings through the world landscapes of public history. This piece focuses on the notion of identity, a central concern in recent political debates and tendencies across the globe. He begins by distinguishing “historical consciousness” and “disciplinary history.” This typologisation leads our contributor to make a number of suggestions for contemporary historical education, which must necessarily correspond to its political framework.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17821

The third week of our April edition features a contribution by Michel Kobelinski (Curitiba, Brazil). The author introduces us to a German painter who emigrated to Paraná at the beginning of the 2nd century and opens with a surprising question: Was Hans Schiefelbein from Düsseldorf actually able to produce Brazilian art and cultural identity? This question requires some sense of the southern Brazilian landscape, its extent, its design, its population and their artistic representation in Schiefelbein’s paintings. In any case, our author leaves no doubt that Schiefelbein and especially his pictures are among the relevant identity markers in Paraná today. So how is it possible to get such identity markers recognised? Our authors suggests that making reference to typical geographical and cultural landscape elements of the reference region seems to be a successful strategy.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17822

Week 4 presents a contribution by Claudia Gatzka (Freiburg/Br., Germany) that proposes a strong, research-based claim on our overall topic. Briefly put, the identificatory charging of “landscape,” and today’s meaning of the term, were invented by the early tourism industry. Indeed, the tourism industry and empathy were born as twins. Landscape became landscape when it was sold as such. Tourism became identity-forming in reference to landscape when a romantic consciousness was monetised. The author refers to Germany’s Rhineland to illustrate their claim.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17823

fig. 4: Gruben. Le Weisshorn (4506 m) vu depuis le chemin du col de Forcletta

Our fifth contributor Roberta Biasillo takes us to a more southerly landscape: Tuscany or, more precisely, the Val d’Orcia. This we reach by following the old trade routes from the Rhineland across the Alpine ridge and the Apennines, on a route taken by so many armies, merchants and poor folk, on tracks laid by Roman road builders. They also trace the invention, or rather the creation, of a landscape from the late Middle Ages to the present. Tourists, however, experience this process as completed. It is handed down and perpetuated within this frame, as if landscapes were timeless. Our author shows how the interaction of politics, representation, art and, last but not least, economic rationality lead to an overall geographic impression that creates identity and cannot be understood in any other way than as a landscape.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17824

These five OPR contributions by renowned scholars from different disciplines constitute the thematic core of our April edition. However, another contribution could easily have been incorporated in their midst, one bridging across to this month’s free parallel programme, our Speaker’s Corner section, which a metaphorical concept of landscape helps us understand as the surveying of a topos-graphy of contemporary public history.

Our Speaker’s Corner feature in week 4 takes us to Ghana, that is, further south, towards the equator, heading south-southwest from Val d’Orcia, for over 6000 kilometres. How easily forgotten is the fact how large Africa is and how close Italy is to Africa. Gideon Baodu, our author, invites us to engage with important aspects of Ghanaian public history. They explain the relations between these aspects, systematically and historically, in their geographical conditionality and postcolonial situativity. The editors are grateful for the author’s important insights and hope to contribute to stripping this landscape of public history of its – or rather, of our mis-perception of its – otherness. The contribution is accompanied by an OPR from Ghana, which we also look forward to.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-18122

Back to the global West and its public history, and to the privileged nature of its problems, which often drive the locals giddy as if there were no tomorrow, as if what is theirs were earth-shattering. Public History Weekly is designed as a disillusionment cell, a place where intellectual agitation becomes calmed and clarified; we seek to understand rather than to intensify conflicts over the public treatment of history. Such coolness is, of course, not always welcome among conflicting parties. Public History Weekly is also a platform for dealing with such conflicts in a civilised manner and with an editorial filter. Everyone is invited to comment (see Guidelines).

Beyond that, we will be publishing a Speaker’s Corner contribution by three historians, Christoph Dartmann, Antje Flüchter und Silke Schwandt, on a debate sparked by a public appeal and a petition, that has since led to the founding of a “network.” It seeks to oppose “all efforts” to restrict “the freedom of research and teaching for ideological reasons.”[10] The three historians take a closer look at the argumentation supporting this appeal from their disciplinary perspectives. The call is not directed specifically at historical scholarship, but a comparatively large number of historians have taken part. The call refers to analogous conflicts in the USA, UK or elsewhere. As such, it reflects an international discourse and thus is certainly interesting for public historians worldwide. Given the controversial nature of the issue within the historical sciences, we have invited two OPRs and are pleased that two renowned colleagues have accepted our invitation.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17995

This brings us to another hot topic in contemporary public history, one even more specific to Germany, but certainly equally relevant worldwide. This concerns the relationship between historical scholarship and historical journalism and its development, which is shaped by digital transformation. On the one hand, this enables scaling information and opinion even outside the long-established feature columns of the major national quality newspapers (via digital review platforms, for example, but also via an open-access journal such as Public History Weekly). On the other, this is not always averse to surrendering the old feuilleton formats via its social media extensions to the dynamics of digital information and the opportunities for scaling opinion.

We will be presenting two contributions on this topic. They are published with a certain delay (regarding the start of the public debate in March 21), due to the planning, editing and translation ongoing behind the scenes. Yet this “time lag” makes for a healthy distance for both authors and audience and makes Public History Weekly a site of reflection that operates at medium speed. The two contributions (a first by (1) Gabriele Metzler, Berlin, and a second by Sonja Dolinsek and Claudia Gatzka (2) discuss an important issue, the relationship between historical scholarship and historical journalism from different institutional perspectives. The two corresponding OPRs promote and strengthen this diversity.

(1) DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-18061

(2) DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-18178

_____________________

Further Reading

- Küster, Hansjörg. 2012. Die Entdeckung der Landschaft: Einführung in eine neue Wissenschaft. Originalausgabe. Beck’sche Reihe 6061. München: Verlag C.H. Beck.

- Ritter, Joachim. 1974. Subjektivität. Sechs Aufsätze. 1. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

- Schama, Simon. 1995. Landscape and Memory. 1st ed. New York: A.A. Knopf : Distributed by Random House.

_____________________

[1] For an account of these events, Cornelius Tacitus, Annalen: deutsche Gesamtausgabe, XIV. Edited by Werner Suerbaum and translated by August Horneffer. (Stuttgart: Kröner, 2018).

[2] Ibid., XIV, p. 10. “But because a landscape does not change its face like a person, and because he always had the frightening sight of that sea and beach before his eyes — some people even thought they could hear the sound of trumpets from the mountains and the woeful clamouring from his mother’s grave — he headed for Naples.”(translated by Mark Kyburz)

[3] Gesualdo Bufalino, Museum der Schatten: Geschichten aus dem alten Sizilien, p. 15. (Ital.: Museo d’ombre, 1982). Translated into German by Maja Pflug. 5.-6. Tsd. (Berlin: Wagenbach, 2001). “For history is not only that of the annals written with fire and sword, but also that which is bound to place, the physical and human environment in which each of us was brought up. History is the gesture with which dough is kneaded in the baking trough or the grain is mown; history is an abrupt nickname, a fitting proverb, the tone of a voice, the shape of a brick, the refrain of a song; in the end, everything that is shaped by human labour and the imagination. Things that lapse before everything else and whose remains — almost — no one cares to preserve.” (translated by Mark Kyburz)

[4] Hans Blumenberg, Arbeit am Mythos (Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp, 1979), pp. 9–39.

[5] Ernst Jünger, Der Waldgang. Edited by Detlev Schöttker (Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 2017).

[6] Rudolf Borchardt, Der Deutsche in der Landschaft (1927) (Berlin: Matthes & Seitz, 2018), p. 496. “The German is at home everywhere and not at home, is at home wherever he is. The world enters him, while he is absorbed by the world. He is the old wanderer of his history, the guest on Earth.” (translated by Mark Kyburz)

[7] See further Marko Demantowsky, “The public history of heimat and the schools,” in: Conflicts in history education in Europe. Political context, history teaching and national identity. Information Age Publishing (IAP), Charlotte NC 2021 (eds. by Ander Delgado, Andy Mycock) [in print]. For a partly identical German version, see “Was soll das bloss mit dieser ‘Heimat’?” In: Geschichtsbewusstsein in der Gesellschaft. Festschrift für Bernd Schönemann. Wochenschau, Schwalbach/Ts. 2021 (eds. Jan M. Hoffrogge et al.) , pp. 170-188.

[8] Arno Borst, “Barbarossa Erwachen – Zur Geschichte der deutschen Identität.” In Identität, eds. Odo Marquard and Karlheinz Stierle, vol. 8: Poetik und Hermeneutik (Munich: W. Fink, 1979), pp. 17–60.

[9] Hansjörg Küster, Geschichte der Landschaft in Mitteleuropa: von der Eiszeit bis zur Gegenwart, Jubilee edition (München: Beck, 2013), pp. 388–393.

[10] “Manifest.” Netzwerk Wissenschaftsfreiheit (blog). February 2021. https://www.netzwerk-wissenschaftsfreiheit.de/.

_____________________

Image Credits

Featured image: Winters bosgezicht by Eugène-Joseph Verboeckhoven (1863), Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, arranged by (c) Moritz Hoffmann 2021.

fig. 1: Golfo di Napoli con Castellammare di Stabia e Vesuvio. Luogo di esposizione sconosciuto by Edmund Berninger (1843-1909) – Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23191054

fig. 2: Strade Ferrate della Sicilia – Tronco Modica – Comiso by Biblioteca comunale Palermo via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

fig. 3: Scheme of identity-related temporally stretched self-relationships in space (c) Marko Demantowsky 2020.

fig. 4: Gruben. Le Weisshorn (4506 m) vu depuis le chemin du col de Forcletta by Guillaume Baviere via Flickr (CC BY 2.0).

Recommended Citation

Demantowsky, Marko: Landscape and Identity. In: Public History Weekly 9 (2021) 3, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17839.

Editorial Responsibility

Moritz Hoffmann / Arthur Chapman

Translated from German by Dr Mark Kyburz (http://www.englishprojects.ch/home)

Copyright (c) 2021 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 9 (2021) 3

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17839

Tags: Africa, Editorial, Heimat, Identity (Identität), Italy (Italien), Landscape, Tuscany (Toskana)

To all our non-English speaking readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 11 languages. Just copy and paste.

I really liked the thought-provoking theme proposed by Marko Demantowsky and the collaborators. Without a doubt, landscape and memory challenge us to think them through the bias of culture, history, identity, besides, of course, the personal perception of each one of us. I understand that the multiple notions of landscape are complex and inseparable from the representations and practices that determine their apprehensions.

Therefore, the historian must study the desires, the forms of intervention, contemplation, and creation that constitute the landscape. Thus, it is necessary to pay attention to the study of groups and individuals who apprehend the landscape in order to understand how this process is associated with the imaginary and the condition of individuals and groups, which are plural and unique at the same time.