Abstract: In Teaching History in the Digital Age, Mills Kelly recounts a teaching anecdote with millennial students. At the beginning of a history class, an avid student informed Kelly that he had “fixed” the Nuremberg video they watched during the previous session.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2015-4576.

Languages: English, Deutsch

In Teaching History in the Digital Age, Mills Kelly recounts a teaching anecdote with millennial students. At the beginning of a history class, an avid student informed Kelly that he had “fixed” the Nuremberg video they watched during the previous session.

“Fixing” History

Stunned, Kelly decided to show this modified version to the class. It was the same Universal Newsreel but much of the music track had been replaced with new background music: bass notes from the movie Jaws and passages from Mozart’s Requiem. As the student then explained, the new music was much more appropriate to the seriousness of the situation. “From now on, Professor Kelly,” he insisted, “you should use my version.” Kelly, the scholarly historian, tried as much as he could to explain that the remix was very creative but not the original source of the time. Unimpressed, the student shrugged his shoulders and replied: “Yeah, but mine’s better.”[1] Welcome to the digital world![2]

The Future is not what it used to be

In his award-winning book, The World is Flat, Thomas Friedman contends that a converging set of factors has drastically changed the world in which we live, turning it into a place where people can “plug, play, compete, connect, and collaborate” in ways never experienced before.[3] Today’s students were born and raised in this world. The generation of “digital natives” has never known a place without personal computers and Internet access. In their language, library is spelled “G-O-O-G-L-E” and the once honoured quality of being “smart” now applies to cellular phones and interactive whiteboards. With this in mind, they naturally expect their education to support their own attitudes toward learning and technology.

Going digital in history

In the field of history, technology has not only affected classroom delivery, it has also impacted on the entire discipline itself, providing new approaches for examining, representing, and sharing knowledge with new communication technologies. In a previous age, researchers faced a scarcity of information. Today, the greatest challenge might well be the “culture of abundance.” As Dan Cohen, executive director of the Digital Public Library of America, illustrates, if a student wants to write a history of the Lyndon Johnson White House she has to analyze 40,000 memos issued during Johnson’s administration. Now if she wants to write about the Clinton White House, she has four million emails to deal with.[4]

Technology and its impact on “doing history”

The impact of technology on history is such that the American Historical Association (AHA) just released the first ever guidelines for the evaluation of digital scholarship in history.[5] Around the world there is growing evidence of this impact, from digital archives and oral history collections through to data management software, serious games, digital learning resources, and MOOCS (massive open online courses). For the last decade, I have been arguing – along with other colleagues – that digital history is transforming the way our students “do history.”[6] Growing evidence now suggests that technology has, indeed, positive impacts on students’ historical thinking and engagement, providing them with tools to investigate the multiple perspectives and relics of the past instead of memorizing a set of historical facts. The Stanford History Education Group (SHEG) is one U.S. initiative intended to implement technology in teaching and assessment with their “Reading like a historian” and “Beyond the Bubble” programs.[7] In Canada, we have also developed our own approach to historical thinking, called the Virtual Historian, in collaboration with the Historical Thinking Project.[8]

Changing the way we “byte” into history

Many educators adhere to this new interactive approach of history. Unfortunately, the education regime that too many students receive does not prepare them for the challenges of the “flat” world. Confronted in their daily lives with an overabundance of information delivered through a myriad of sources, students still receive a history “combo” in neatly packaged lectures, uncontroversial textbook stories, and accompanying worksheets that evade multiple perspectives and critical interpretation. How, then, do we close the gap between “old world teaching” and the “21st century world that students are linked to by their smartphones”?[9] There is no simple answer to this question.

Technological amplification as a challenge

Many educational institutions have eagerly embraced the digital revolution, adopting novel classroom technologies and raising awareness about the use of the Internet. But these do not, in and of themselves, make informed citizens in the 21st century. Technology, as Kentaro Toyama of the University of Michigan School of Information puts it, “doesn’t add a fixed benefit. Instead, it amplifies underlying human forces.”[10] Amplification helps to explain all sorts of human-technology interactions. It helps to explain why, for instance, widespread Internet has promoted free speech and access to information in democratic countries but dissent and propaganda in autocratic regimes. It also helps to explain why MOOCS are completed almost exclusively by serious-minded, well-educated citizens and not by unemployed high-school dropouts.

Amplification and the need for teacher agency

Applied to history education, amplification helps us to understand what it might be possible to do with our digital natives. Simply providing students with a million free digital images from the new British Library Flickr’s site is unlikely to further their critical reading and historical thinking skills.[11] Organizations and people who are making a positive difference in the field are those who have been able to leverage technology as a tool to engage their students in “doing history” and in ways that are consonant with a given societal culture and established educational values.[12] Toyama’s notion of amplification thus reaffirms the importance of teacher agency in a digital age. It reminds us that more technologies will not help educators if they are headed in the wrong direction. Successful digital history education must start with a deep understanding of how historical knowledge is constructed and shared.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Kee, Kevin (ed.). Past Play: Teaching and Learning History with Technology. (Ann Arbour, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2014).

- Kelly, Mills. Teaching History in the Digital Age (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013).

- Lévesque, Stéphane. Thinking Historically: Educating Students for the 21st Century (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008).

Web Resources

- Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (RRCHNM) at George Mason University: https://chnm.gmu.edu (last accessed 30.09.2015).

- Perspectives on History, American Historical Association: https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/may-2009/intersections-history-and-new-media/what-is-digital-history (last accessed 30.09.2015).

- Digital Public Library of America: http://dp.la (last accessed 30.09.2015).

____________________

[1] Mills Kelly, Teaching History in the Digital Age (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013).

[2] I owe special thanks to my colleague Paul Zanazanian (paul.zanazanian@mcgill.ca) for his supportive comments and critical insight.

[3] Thomas Friedman, The World is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005).

[4] As cited in Kevin Kee, How to energize scholarship for the digital age, University Affairs (April 2014). http://www.universityaffairs.ca/features/feature-article/how-to-energize-scholarship-for-the-digital-age (accessed 10.09.15)

[5] American Historical Association, Guidelines for the Evaluation of Digital Scholarship in History (2015). http://www.historians.org/Documents/Teaching%20and%20Learning/Current%20Projects/Digital%20Scholarship%20Evaluation/Guidelines%20for%20the%20Professional%20Evaluation%20of%20Digital%20Scholarship.pdf (last accessed 10.09.15).

[6] On the notion of “doing history” as a discipline-based inquiry, see for instance David Kobrin, Ed Abbott, John Ellinwood and David Horton, Learning History by Doing History, Educational Leadership, 50, 7 (1993), 39-41; Linda Levstik and Keith Barton, Doing History: Investigating With Children in Elementary and Middle Schools, 4th ed. (New York: Routledge, 2011); Mark Donnelly and Claire Norton, Doing History (Abingdon : Routledge, 2011); and Harry Havekes, Peter Coppen, Johan Luttenberg and Carla van Boxtel, Knowing and doing history: a conceptual framework and pedagogy for teaching historical contextualisation, International Journal of Historical Learning, Teaching and Research, 11 (2012), 72-93.

[7] Stanford History Education Group (SHEG). Charting the Future of Teaching the Past. https://sheg.stanford.edu (last accessed 10.09.15).

[8] The Virtual Historian / L’historien virtuel. http://www.virtualhistorian.ca ; and The Historical Thinking Project http://historicalthinking.ca (last accessed 10.09.15). Other initiatives include the National History Education Clearinghouse (www.TechingHistory.org), the Chinese Canadian Stories Portal (http://chinesecanadian.ubc.ca); the Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History (www.canadianmysteries.ca); and the Centre for Oral History and Digital Storytelling (http://storytelling.concordia.ca) – (all last accessed 10.09.15).

[9] Sam Wineburg, Changing the Teaching of History, One Byte at a Time. Edutopia (November 14, 2013). http://www.edutopia.org/blog/changing-the-teaching-of-history-sam-wineburg (last accessed 10.09.15).

[10] Kentaro Toyama, It may be the age of machines, but it’s up to humans to save the world, The Guardian (June 11, 2015). http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/jun/11/age-of-machines-humans-save-the-world (last accessed 10.09.15).

[11] See https://www.flickr.com/photos/britishlibrary (last accessed 10.09.15).

[12] Such considerations for implementing technology in history education help understand why different countries and jurisdictions have adopted distinctive approaches to digital history, some focusing more explicitly on historical literacy and others on inquiry-based learning, historical perspective-taking or historical thinking concepts.

_____________________

Image Credits

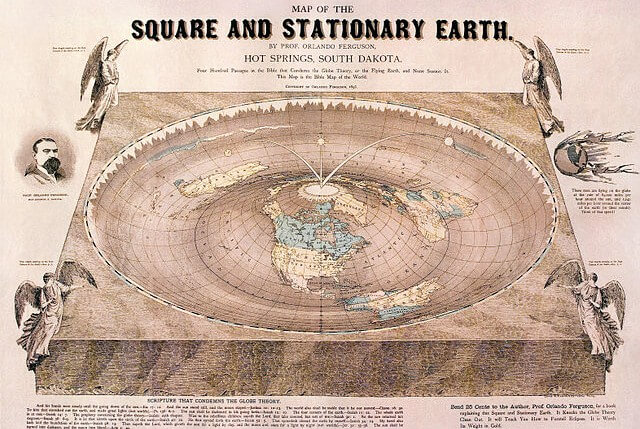

A “flat-Earth” map drawn by Orlando Ferguson in 1893. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Orlando-Ferguson-flat-earth-map_edit.jpg (last accessed 21.09.2015)

Recommended Citation

Levesque, Stéphane: Breaking away from passive history in the digital age. In: Public History Weekly 3 (2015) 30, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2015-4576.

In seinem Buch Teaching History in the Digital Age erzählt Mills Kelly eine Geschichte von seinem Unterricht mit Studierenden der Generation Y. Am Anfang einer Geschichtsstunde berichtete ein eifriger Student, dass er das Video des Nürnberger Kriegstribunals, das in der vorigen Stunde vorgeführt wurde, “repariert” habe.

Geschichte “reparieren”

Völlig verblüfft entschied Kelly, der Gruppe diese modifizierte Version zu zeigen. Es war dieselbe Wochenschau von Universal, aber einen grossen Teil der Musik auf der Tonspur hatte der Student durch neue Hintergrundmusik ersetzt: mit Bassklängen aus dem Film Jaws und Passagen aus Mozarts Requiem. Wie der Student dann erklärte, passte die neue Musik viel besser zur Ernsthaftigkeit der Situation. “Ab sofort, Professor Kelly” insistierte er, “sollten Sie meine Version verwenden.” Kelly, der Geschichtswissenschaftler, versuchte so ausführlich wie möglich zu erklären, daß der Remix zwar sehr kreativ, aber nicht die Originalquelle aus der Zeit sei. Unbeeindruckt zuckte der Student mit den Schultern und antwortete, “Yeah, aber meine ist besser.”[1] Willkommen in der digitalen Welt![2]

Die Zukunft ist nicht das, was sie einmal war

Thomas Friedman behauptet in seinem preisgekröntem Buch The World is Flat, dass eine konvergierende Menge von Faktoren die Welt, in der wir leben, drastisch verändert hat. Sie ist jetzt ein Ort, wo Menschen auf eine bisher nicht bekannte Weise “plug, play, compete, connect, and collaborate” (einstöpseln, spielen, wetteifern, sich verbinden und kollaborieren) können.[3]

Die heutigen Studierenden sind in dieser Welt geboren und groß geworden. Die Generation der “digital natives” hat nie einen Ort ohne PCs und Internetzugang gekannt. In deren Sprache wird Bibliothek mit “G-O-O-G-L-E” buchstabiert und die einstmals ehrenhafte Eigenschaft, “smart” zu sein, bezieht sich heute auf Handys und interaktive Whiteboards. Angesichts dessen erwarten die Jugendlichen natürlich, dass ihr Unterricht die eigenen Einstellungen in Bezug auf Lernen und Technologie unterstützt.

Digitaler Wandel und Geschichte

Im Bereich Geschichte hat Technologie nicht nur den Geschichtsunterricht beeinflußt; sie hat auf die ganze Disziplin eingewirkt und neue Möglichkeiten für das Prüfen, Darstellen und Teilen von Wissen mit neuen Kommunikationstechnologien bereitgestellt. Früher mussten sich WissenschaftlerInnen mit dem Umstand auseinandersetzen, dass der Zugang zu Wissen eingeschränkt war. Heute ist die “Kultur der Fülle” die größte Herausforderung. Dan Cohen, Leiter der Digital Public Library of America, bringt die Situation wie folgt auf den Punkt: Möchte eine Studierende die Geschichte des Weißen Hauses von Lyndon Johnson schreiben, muß sie 40,000 Kurzmitteilungen analysieren, die während der Regierungszeit von Johnson erstellt wurden. Will sie jedoch über das Weiße Haus unter Clinton schreiben, muß sie sich mit vier Millionen E-Mails auseinandersetzen.[4]

Technologie und “Geschichte machen”

Die Auswirkungen des digitalen Wandels auf Geschichte sind derart gross geworden, daß die American Historical Association (AHA) soeben die allerersten Richtlinien für die Evaluierung der digitalen Forschung in Geschichte veröffentlicht hat.[5] Die Auswirkungen des digitalen Wandels sind überdies weltweit in weiteren Phänomenen zu beobachten: in digitalen Archiven und Sammlungen von Oral History bis hin zu Software für Datenverwaltung, serious games, digitalen Lernressourcen und MOOCS (massive open online courses). Zusammen mit anderen KollegInnen plädiere ich seit zehn Jahren dafür, dass digitale Geschichte die Art und Weise verändert, wie unsere Studierende “Geschichte machen”.[6] Immer mehr Hinweise deuten darauf hin, dass Technologie in der Tat positive Auswirkungen auf das historische Denken und das Engagement der Studierenden hat. Sie gibt ihnen das Handwerkszeug, mit dem sie Multiperspektivität und Überreste der Vergangenheit untersuchen können, anstatt historische Fakten auswendig zu lernen. Die Stanford History Education Group (SHEG) ist eine US-amerikanische Initiative, die mit Programmen wie “Reading like a historian” und “Beyond the Bubble” das Ziel verfolgen, digitale Technologien in der Lehre und bei Prüfungen einzusetzen.[7] In Kanada haben wir in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Historical Thinking Project unseren eigenen Ansatz zum historischen Denken entwickelt: der “Virtual Historian“.[8]

Neue Wege zur Geschichte

Zwar halten sich viele Lehrpersonen an diesen neuen interaktiven Ansatz, Geschichte zu betreiben. Doch leider bereiten die Unterrichtsformate, die die meisten SchülerInnen erhalten, sie nicht auf die Herausforderungen vor, mit denen die “Welt als Scheibe” sie konfrontiert. Obwohl sie in ihrem täglichen Leben mit einer Überfülle von Information aus einer Vielzahl von Quellen konfrontiert werden, erhalten die SchülerInnen in ihrem Geschichtsunterricht immer noch eine Kombipackung aus säuberlich geschnürten Vorlesungen und unumstrittenen Lehrbuchgeschichten mit den dazugehörigen Arbeitsblättern, die Multiperspektivität und kritische Interpretationen vermeiden. Wie sollen wir also die Lücke schließen zwischen der “Lehre der alten Welt” und der Welt “des 21. Jahrhunderts, mit der SchülerInnen durch ihre Smartphones verbunden sind”?[9] Es gibt keine einfache Antwort auf diese Frage.

Technologische Erweiterung als Herausforderung

Viele Bildungsinstitutionen haben die digitale Revolution freudig mit der Verwendung neuartiger Technologien in den Unterrichtsräumen und mit einer verstärkten Bewußtseinsbildung in Bezug auf die Verwendung des Internets aufgegriffen. Allerdings reicht dies nicht aus, um die Heranwachsenden zu informierten BürgerInnen des 21. Jahrhunderts werden zu lassen. Technologie, wie Kentaro Toyama von der University of Michigan School of Information Technology es formuliert, “fügt keinen festen Mehrwert hinzu. Sie erweitert vielmehr die zugrundeliegenden menschlichen Kräfte.”[10] Das Konzept der “Erweiterung” ermöglicht, alle möglichen Arten von Interaktionen zwischen Menschen und Technologie zu erklären. Sie hilft zum Beispiel auch zu verstehen, warum das weitverbreitete Internet in demokratischen Ländern freie Meinungsäußerung und Zugang zu Information, in autokratischen Regimes jedoch Widerstand und Propaganda gefördert hat. Das Konzept macht auch verständlich, warum MOOCS fast ausschließlich von ernsthaften, gut ausgebildeten BürgerInnen und nicht von arbeitslosen SchulabbrecherInnen absolviert werden.

“Erweiterung” und der Bedarf nach Lehrerhandeln

In Bezug auf den Geschichtsunterricht kann das Konzept Einsichten dazu vermitteln, was wir möglicherweise mit unseren “digital natives” erreichen könnten. SchülerInnen lediglich eine Million kostenlose digitale Abbildungen aus der Flickr-Seite der British Library zur Verfügung zu stellen, wird ihre Fähigkeiten zum kritischen Lesen und historischen Denken vermutlich weder erweitern noch vertiefen.[11] Die Organisationen und Menschen, die positive Veränderungen auf diesem Gebiet bewirken, sind diejenigen, die Technologie wirksam – als ein Werkzeug – einsetzen. Dieses Werkzeug ermöglicht es den SchülerInnen, sich mit Geschichte zu beschäftigen, sie “zu machen”; und zwar auf einer Weise, die mit einer bestimmten gesellschaftlichen Kultur und etablierten Bildungsintentionen im Einklang sind.[12] Toyamas Konzept der Erweiterung bestätigt daher nochmals, wie wichtig das Lehrerhandeln im digitalen Zeitalter ist. Das Konzept erinnert uns daran, dass mehr Technologie den Lehrpersonen nicht helfen wird, wenn sie nicht passende Ansätze im Geschichtsunterricht verfolgen. Ein erfolgreicher, digital gestützter Geschichtsunterricht benötigt ein tiefes Verständnis dafür, wie geschichtliches Wissen konstruiert und gemeinsam benutzt wird.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Kee, Kevin (ed.): Past Play. Teaching and Learning History with Technology, Ann Arbour 2014.

- Kelly, Mills: Teaching History in the Digital Age, Ann Arbor 2013.

- Lévesque, Stéphane: Thinking Historically: Educating Students for the 21st Century, Toronto 2008.

Webressourcen

- Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (RRCHNM) an der George Mason University: https://chnm.gmu.edu (Letzter Zugriff am 30.09.2015).

- Perspectives on History, American Historical Association: https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/may-2009/intersections-history-and-new-media/what-is-digital-history (Letzter Zugriff am 30.09.2015).

- Digital Public Library of America: http://dp.la (Letzter Zugriff am 30.09.2015).

____________________

[1] Mills Kelly, Teaching History in the Digital Age (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013).

[2] Meinem Kollegen Paul Zanazanian (paul.zanazanian@mcgill.ca) schulde ich einen besonderen Dank für seine hilfreiche Kommentare und sein kritisches Verständnis.

[3] Thomas Friedman, The World is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005).

[4] Zitiert nach Kevin Kee, How to energize scholarship for the digital age, University Affairs (April 2014). http://www.universityaffairs.ca/features/feature-article/how-to-energize-scholarship-for-the-digital-age (Letzter Zugriff am 10.09.15)

[5] American Historical Association, Guidelines for the Evaluation of Digital Scholarship in History (2015). http://www.historians.org/Documents/Teaching%20and%20Learning/Current%20Projects/Digital%20Scholarship%20Evaluation/Guidelines%20for%20the%20Professional%20Evaluation%20of%20Digital%20Scholarship.pdf (Letzter Zugriff am 10.09.15).

[6] Für weitere Informationen zum Konzept des „Geschichte machens“ als eine disziplinbasierte Recherche, siehe zum Beispiel David Kobrin, Ed Abbott, John Ellinwood and David Horton, Learning History by Doing History, Educational Leadership, 50, 7 (1993), 39-41; Linda Levstik and Keith Barton, Doing History: Investigating With Children in Elementary and Middle Schools, 4th ed. (New York: Routledge, 2011); Mark Donnelly and Claire Norton, Doing History (Abingdon : Routledge, 2011); and Harry Havekes, Peter Coppen, Johan Luttenberg and Carla van Boxtel, Knowing and doing history: a conceptual framework and pedagogy for teaching historical contextualisation, International Journal of Historical Learning, Teaching and Research, 11 (2012), 72-93.

[7] Stanford History Education Group (SHEG). Charting the Future of Teaching the Past. https://sheg.stanford.edu (Letzter Zugriff am 10.09.15).

[8] The Virtual Historian / L’historien virtuel. http://www.virtualhistorian.ca; und The Historical Thinking Project http://historicalthinking.ca (Letzter Zugriff am 10.09.15). Weitere Initiative umfassen das National History Education Clearinghouse (www.TechingHistory.org), das Chinese Canadian Stories Portal (http://chinesecanadian.ubc.ca); das Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History (www.canadianmysteries.ca); und das Centre for Oral History and Digital Storytelling (http://storytelling.concordia.ca) – (Bei allen letzter Zugriff am 10.09.15).

[9] Sam Wineburg, Changing the Teaching of History, One Byte at a Time. Edutopia (November 14, 2013). http://www.edutopia.org/blog/changing-the-teaching-of-history-sam-wineburg (Letzter Zugriff am 10.09.15).

[10] Kentaro Toyama, It may be the age of machines, but it’s up to humans to save the world, The Guardian (June 11, 2015). http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/jun/11/age-of-machines-humans-save-the-world (Letzter Zugriff am 10.09.15).

[11] See https://www.flickr.com/photos/britishlibrary (Letzter Zugriff am 10.09.15).

[12] Solche Überlegungen zum Einsatz von Technologie im Geschichtsunterricht helfen zu verstehen, warum unterschiedliche Länder und Zuständigkeitsbereiche jeweils eigene Zugänge gewählt haben. Manche legen explizit mehr Wert auf historische Bildung, andere auf forschungsbasiertes Lernen, auf die Übernahme von historischen Perspektiven oder auf Konzepte historischen Denkens.

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

Karte einer “flachen Erde” von Orlando Ferguson in 1893. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Orlando-Ferguson-flat-earth-map_edit.jpg (letzter Zugriff am 21.09.2015)

Übersetzung aus dem Englischen

Jana Kaiser (kaiser at academic-texts.de)

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Levesque, Stéphane: Schluss mit der “passiven Geschichte” im digitalen Zeitalter. In: Public History Weekly 3 (2015) 30, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2015-4576.

Copyright (c) 2015 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact: elise.wintz (at) degruyter.com.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 3 (2015) 30

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2015-4576

Tags: Canada (Kanada), Digital Change (Digitaler Wandel), History Teaching (Geschichtsunterricht), Teaching Methods (Methodik)