Abstract: Social Media are “a group of Internet-based applications that build on the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0, and that allow the creation and exchange of user-generated content.”[1] They facilitate various forms of web communication between individuals and communities. They can bring users together to discuss common issues and to share traces of the past. Local communities’ engagement with the past, mediated or not, are made possible through Web 2.0 practices. New virtual contacts could be built when communities are no longer present in physical spaces.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2015-4706.

Languages: English, Deutsch, Français

Social Media are “a group of Internet-based applications that build on the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0, and that allow the creation and exchange of user-generated content.”[1] They facilitate various forms of web communication between individuals and communities. They can bring users together to discuss common issues and to share traces of the past. Local communities’ engagement with the past, mediated or not, are made possible through Web 2.0 practices. New virtual contacts could be built when communities are no longer present in physical spaces.[2]

Everybody’s got talent: user-generated knowledge

If social media allow dispersed communities to reconnect online and share their memories, today, understanding how common people use social media and play with history tells us many things about which pasts are important in our present.[3]

Everybody promotes her/himself. TV “reality shows” such as Got Talent[4] are the most followed TV broadcasts worldwide because they select unknown people and connect them with an audience. These shows reveal unexpressed skills and creative capacities the same way online social media websites crowd-source knowledge and reconnect with the past. Like TV talent shows, social media allow different publics to promote themselves, their family history, and their communities.

Sociologist Pierre Bourdieu defined the systematic repetition of similar family photographs as emblematic of popular behaviour and culture.[5] Sharing different generations’ family pictures in social media shapes collective memories.[6] On the other hand, such popular demand for genealogy[7] only scratches the surface of major events in history and is often disconnected from “big history” and broader contexts. But photography, in social media, describes popular behaviours – “selfies” today – [8] and, thanks to linked data technologies, Google Maps, and Street View, adds spatial dimensions and time boundaries to individual memories.

Pinning your images with Historypin, a digital time machine

“Historypin is a digital time machine that creates a new way for the world to see and share history.”[9] Linked data and the Semantic Web connect digital contents, combining primary sources with geography.[10] Old pictures can be “pinned” in the present: family pasts may be re-enacted today. Heritage institutions, but also common people, organize forms of storytelling because the technology is easy. Public historians take Historypin seriously to engage with specific communities.[11] Using Historypin, the American National Archives is now everywhere outside the building in the virtual space[12] and solicits everybody’s contribution to historical archives, inviting the wider public to “pin your history to the world.”[13] In Florence, during a public exhibition (2014) commemorating the 70th anniversary of the end of the German occupation,[14] citizens brought their documents on site, using the MemorySharing project. Old 1944 documents were scanned and included in today’s maps of Florence. New Zealand soldiers are now re-enacted directly on Google Street View.[15] You can fade the vintage picture[16] to see the contemporary layer of the street.

Could academic historians use the potential of digital public history, with Historypin, a tool that makes it easy to re-enact even difficult pasts? Alon Confino tried to reconstruct the pre-1948 invisible Palestinian past of Tantura, Dor in today’s Israel. Confino studied cadastral maps, aerial photography, and images of Palestinians recorded prior to May 22–23, 1948. But user-generated content from social media would add original Palestinian diaspora documents: re-enacting 1948 Palestinian memories should be possible.[17]

Visual narrative public history

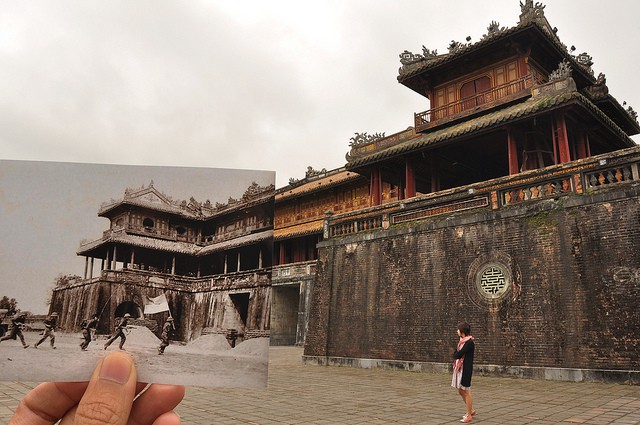

Inspired by a photograph, Michael Hughes’ Flickr project “Souvenirs”,[18] Looking into the Past merges past and present in a unique image.[19] “Ghosting family pasts”, thanks to digital technologies, is very popular for resuscitating memories. Merging old pictures and recent images shortens the digital timeline and activates different regimes of historicity in the present.[20]

Emblematic of many others projects around the world, the Past Present Project in Tumblr[21] publishes family pictures where past and present overlap.[22] Images showing the pastness of places shape a nostalgic present, such as the merged urban temporalities of the Hungarian artist Zoltán Kerényi,[23] or Hebe Robinson’s Northern Norway Echoes, a project placing old family photos from a Lofoten fishing village, abandoned after WW2, in today’s landscape.[24] Sometimes called rephotography,[25] these new images contain different time layers in one unique image. Even WW1 images are “ghosted” in a past-present continuum.[26] The same is done with WW2 images by the Russian photographer Sergey Larenkov in Link to the Past.[27] The author of a website about Krakow “looks for very old photos of the city and takes new ones from the very same spot, so my readers can compare and see what has changed”.[28] Keith Jones, in Liverpool then and now,[29] lets us discover “blended shots”: old black and white images merged with colour images.[30]

Past-present relationships in photographs

The Italian photographer, Isabella Balena, took pictures of the Gothic Line ruins that stopped the allied offensive in 1944 in central Italy sixty years after the event. Ci resta il nome, a photographic journey through the memory of WW2 in Italy is a good example of visual narrative public history.[31] What is important in Balena’s systematic reproduction of monuments and traces of the violent past is to show how the place where Mussolini was shot in April 1945 tells about both presentism and oblivion and is open to the present and new futures.

But photography may also show that the present has lost its connection with the past. Total disconnection with history is what Serge Gruzinski demonstrates with the cover picture of his book, L’Histoire pour quoi faire?:[32] young, post-colonial Algerians playing soccer. Their goalkeeper stands in front of an ancient Roman arch, a symbol of lost memories. The arch does not mean anything to them. Instead, in the context of today’s Isis campaigns, the Islamic State extremists destroy past heritages, so that history could be rewritten and memory cancelled forever.[33]

_____________________

Further Reading

- François Hartog: Régimes d’historicité: présentisme et expériences du temps., Paris: Seuil, 2003 (Regimes of historicity: presentism and experiences of time, translated by Saskia Brown, New York: Columbia University Press, 2015.

- Serge Gruzinski: L’Histoire pour quoi faire?, Paris: Fayard, 2012.

- Serge Noiret: “Nulla sarà più come prima: considerazioni sul Digital Turn e le fonti fotografiche dal punto di vista della storiografia.” in Gian Piero Brunetta and Carlo Alberto Zotti Minici (eds.): La fotografia come fonte di storia, atti del convegno (Venezia, 4-6 ottobre 2012), Venezia, Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, 2014, pp.248-268.

Web Resources

- 1940-1944 Firenze in guerra: http://www.firenzeinguerra.com (Last accessed 5.10.2015)

- Historypin – a global community collaborating around history: http://www.historypin.org (Last accessed 5.10.2015)

- Flickr Group “Looking Into the Past”: http://www.flickr.com/groups/lookingintothepast/ (Last accessed 5.10.2015)

____________________

[1] Andreas M. Kaplan, and Michael Haenlein, “Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media”, in Business Horizons, 53/1, 2010 pp. 59-68.

[2] Dario Miccoli studies how the Jewish diaspora from the Maghreb is today “reconnected” through the web and social media. See “Digital museums: narrating and preserving the history of Egyptian Jews on the Internet”, in E. Trevisan Semi, D. Miccoli and T. Parfitt (eds.), Memory and Ethnicity. Ethnic Museums in Israel and the Diaspora, Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2013, pp.195-222; “Les Juifs du Maroc, Internet et la construction d’une diaspora numérique”, in Expressions Maghrébines, 13/1, 2014, pp.75-94.

[3] André Gunthert: “Shared Images”, in Études photographiques, 24, novembre 2009, http://etudesphotographiques.revues.org/3436 (Last accessed 5.10.2015); “L’image conversationnelle”, in Études photographiques, 31, 2014, http://etudesphotographiques.revues.org/3387 (Last accessed 5.10.2015).

[4] A list of countries offering, after the USA in 2006 and GB in 2007, an emulation of Got Talent is available in Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Got_Talent; America’s Got Talent (2006), http://www.nbc.com/americas-got-talent; La France a un incroyable talent (2006), http://www.m6.fr/emission-la_france_a_un_incroyable_talent/; Britain’s got talent http://www.itv.com/britainsgottalent; general information in Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Britain%27s_Got_Talent (All last accessed 5.10.2015).

[5] Pierre Bourdieu, Luc Boltanski, Roger Castel and Philippe de Vendeuvre: Photography, a Middle-Brow Art, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990.

[6] Richard Chalfen, “La photo de famille et ses usages communicationnels”, Études photographiques, n. 32, 2015, http://etudesphotographiques.revues.org/3502 (Last accessed 5.10.2015).

[7] Jerome De Groote: “International Federation for Public History Plenary Address: On Genealogy”, in The Public Historian, Vol. 37, No. 3, August 2015, pp. 102-127, DOI: 10.1525/tph.2015.37.3.102 (Last accessed 5.10.2015).

[8] André Gunthert: “The consecration of the selfie”, in Études photographiques, 32, 2015, http://etudesphotographiques.revues.org/3537 (Last accessed 5.10.2015)

[9] Historypin in Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historypin (Last accessed 5.10.2015); see also Hunter Skipworth: Historypin turns Google Street View into a window on the past, June 21, 2010, The Telegraph, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/google/7854922/Historypin-turns-Google-Street-View-into-a-window-on-the-past.html (Last accessed 5.10.2015); Beat Brüsch: “L’histoire en noir et blanc”, in: Mots d’Image, http://www.motsdimages.ch/L-histoire-en-noir-et-blanc.html

[10] “A global community collaborating around history […]”, http://www.historypin.com/ (Last accessed 5.10.2015). Historypin was created by the non-profit company Shift with support from Google and launched at the Museum of the City of New York in July 2011. “Enabling networks of people to share and explore local history, make new connections and reduce social isolation” was the goal of the company. See Historypin, http://www.shiftdesign.org.uk/products/historypin/ (Last accessed 5.10.2015).

[11] Meg Foster: “Online and Plugged In? Public History and Historians in the Digital Age”, in Public History Review, Vol.21, 2014, pp. 1-19, http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/phrj/article/view/4295/4601 (Last accessed 5.10.2015)

[12] Kris Jarosik: “Primary Sources With Some Help from Historypin”, in The National Archives Education Updates, http://education.blogs.archives.gov/2014/12/16/primary-sources-on-history-pin/ (Last accessed 5.10.2015).

[13] NARA, http://www.archives.gov/social-media/historypin.html (Last accessed 5.10.2015).

[14] http://www.regione.toscana.it/-/1940-1944-firenze-in-guerra (Last accessed 5.10.2015); Filippo Macelloni and Lorenzo Garzella: MemorySharing a Firenze, http://www.firenzeinguerra.com/memorysharing/ (Last accessed 5.10.2015). Francesco Cavarocchi and Valeria Galimi: Firenze in Guerra, 1940-1944, Florence: Firenze University Press, 2014, pp. XXIV-XXV.

[15] The historic centre of Florence on a Google map is now available with new, embedded documents from 1944. This is the direct link with geographical coordinates:

https://www.historypin.org/map/#!/geo:43.789874,11.271481/zoom:13/date_from:1944-01-01/date_to:1944-12-31/ (Last accessed 5.20.2015).

[16] Kaye, George Frederick, 1914-2004. Looking towards the Porta Romana in southern Florence, Italy, in World War II, http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22827427 (Last accessed 5.10.2015)

[17] Alon Confino : “Miracles and Snow in Palestine and Israel: Tantura, a History of 1948.”, in Israel Studies, vol. 17, n. 2, 2012, pp. 25-61, (photos are published on pages 44-55).

[18] https://www.flickr.com/photos/michael_hughes/sets/346406/ (Last accessed 5.10.2015).

[19] Ghosting the Past is the title of a picture showing two generations of the same family pausing on Capitol Hill. Like their grandparents, the next generation visited the same “realm of American memory”. (Looking into the Past http://www.flickr.com/groups/lookingintothepast/ (Last accessed 5.10.2015)).

[20] François Hartog: Regimes of historicity: presentism and experiences of time (translated by Saskia Brown), New York: Columbia University Press, 2015.

[21] Christian Carollo’s Past Present Project in Tumblr, http://pastpresentproject.com; The Past Present Project in Instagram, https://instagram.com/sayhellotoamerica/; The Past Present Project in Facebook https://www.facebook.com/pastpresentproject (All last accessed 5.10.2015).

[22] “I wondered,” said the photographer Christian Carollo, “what if I could replicate my grandfather’s photograph 30 years later?” http://pastpresentproject.com/about (Last accessed 5.10.2015).

[23] 25 photos du passé se superposent avec le présent pour vous faire découvrir leurs histoires

http://soocurious.com/fr/25-photos-du-passe-se-superposent-avec-le-present-pour-vous-faire-decouvrir-leurs-histoires/ (Last accessed 5.10.2015)

[24] Hebe Robinson: Echoes, http://www.heberobinson.com/#mi=2&pt=1&pi=10000&s=0&p=1&a=0&at=0 (Last accessed 5.10.2015)

[25] Loïc Haÿ: Quand la rephotographie rencontre le numérique, https://tackk.com/rephotographie (Last accessed 5.10.2015)

[26] Pictured: Fascinating World War One photographs mixed with today’s modern landscapes, April 22, 2014, http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/world-war-one-photographs-mixed-3433146 (Last accessed 5.10.2015).

[27]Sergey Larenkov: Связь времен / Link to the Past, URL: http://sergey-larenkov.livejournal.com

[28] Photos are divided; the old black and white image abuts the new one in full colour. The viewer may cancel parts – or the entirety – of one of the two combined images. (Kuba: Dawno temu w Krakowie, http://www.dawnotemuwkrakowie.pl/english/) (Last accessed 5.10.2015).

[29] Keith Jones: Liverpool Then and Now, https://www.flickr.com/photos/keithjones84/sets/72157632063149974/ (Last accessed 5.10.2015).

[30] Liverpool Then and Now, https://www.facebook.com/LiverpoolThenAndNow (Last accessed 5.10.2015)

[31] Isabella Balena: Ci resta il nome., Milano: Mazzotta, 2004 and http://isabalena.photoshelter.com/#!/about (Last accessed 5.10.2015).

[32] Serge Gruzinski: L’Histoire pour quoi faire?, Paris: Fayard, 2012, pp.21-24.

[33] Isis Video Claims Attack On Unesco Iraq World Heritage Site, https://youtu.be/iAWQHWU1H94 (Last accessed 5.10.2015).

_____________________

Image Credits

© Khánh Hmoong: Citadel Gate, Huế 1968 12 March 2012 in: Looking into the Past, Vietnam, Flickr https://www.flickr.com/photos/hmoong/6976527765/in/gallery-jasonepowell-72157632522529341/ (Last accessed 5.10.2015).

Recommended Citation

Noiret, Serge: Digital Public History narratives with Photographs. In: Public History Weekly 3 (2015) 31, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2015-4706.

Soziale Medien sind “eine Gruppe internetbasierter Anwendungen, die auf den ideologischen und technologischen Fundamente des Web 2.0 aufbauen und sowohl Erzeugung wie Austausch von Inhalten ermöglichen, die von Nutzern erstellt werden.”[1] Sie begünstigen unterschiedliche Arten der Kommunikation zwischen Einzelnen und Gemeinschaften. Sie können NutzerInnen zusammenbringen, um gemeinsame Sachverhalte zu diskutieren und Spuren der Vergangenheit miteinander zu teilen. Die Nutzung von Web 2.0-Technologien ermöglicht lokalen Gemeinschaften eine intensivere Auseinandersetzung mit der Vergangenheit, mit und ohne Vermittlung durch Dritte. Durch das Knüpfen von neuen, virtuellen Kontakten entstehen Gemeinschaften, die gar nicht mehr in physischen Räumen vorhanden sind.[2]

Alle haben Talent: nutzergeneriertes Wissen

Wenn es soziale Medien verstreuten Gemeinschaften heutzutage ermöglichen, sich online wieder miteinander zu verbinden und ihre Erinnerungen zu teilen, dann kann uns ein Verständnis dafür, wie normale Menschen diese Medien benutzen und mit Geschichte spielen, viel darüber sagen, welche Vergangenheiten für unsere Gegenwart wichtig sind.[3]

Jede/r wirbt für sich. Reality-Shows im Fernsehen, wie Got Talent[4], sind weltweit die meistgesehenen Fernsehsendungen, weil sie unbekannte Menschen aussuchen und sie einem breiten Publikum vorstellen. Diese Shows enthüllen bislang unbekannte Fähigkeiten und kreative Kapazitäten auf dieselbe Weise wie die Webseiten der sozialen Medien Wissen durch “crowd-sourcing” erschließen und sich mit der Vergangenheit auseinandersetzen. Wie die Talent-Shows im Fernsehen ermöglichen die sozialen Medien unterschiedlichen Publikumsgruppen, für sich, ihre Familiengeschichten und ihre Gemeinschaften zu werben.

Pierre Bourdieu definierte die systematische Wiederholung von ähnlichen Familienfotos als sinnbildlich für populäres Verhalten und populäre Kultur.[5] Gemeinsames Teilen von Familienbildern der unterschiedlichen Generationen in den sozialen Medien formt kollektive Erinnerungen.[6] Auf der anderen Seite kratzt der weitverbreitete Wunsch nach Genealogie[7] nur an der Oberfläche bedeutender Ereignisse der Geschichte und ist oft von der “großen Geschichte” und dem tieferen Verständnis weitergehender Zusammenhänge abgekoppelt. Doch in den sozialen Medien bildet Fotografie einerseits populäre Verhaltensweisen ab – “Selfies”[8] – und vermag dank verknüpfenden Datentechnologien wie in Google Maps und Google Street View den individuellen Erinnerungen räumliche Dimensionen und zeitliche Grenzen zu geben.

Bilder anstecken mit Historypin, einer digitalen Zeitmaschine

“Historypin ist eine digitale Zeitmaschine, die neue Möglichkeiten schafft, wie die Welt Geschichte sieht und teilt.” [9] Verknüpfte Daten und das Semantic Web können digitale Inhalte verbinden, sie ermöglichen zum Beispiel die Kombination von Quellen mit geographischen Informationen.[10] Alte Bilder können in der Gegenwart “gepinnt” werden: Damit können Familienvergangenheiten heute nachgestellt werden. Sowohl Kulturerbe-Institutionen als auch normale Menschen organisieren Formen des Geschichte-Erzählens, weil die Technologie einfach zu handhaben ist. VertreterInnen der Public History betrachten Historypin als eine ernsthafte Möglichkeit, gezielt mit bestimmten Gemeinschaften in Kontakt zu treten.[11] Dank Historypin sind die American National Archives überall außerhalb des Gebäudes im virtuellen Raum[12] präsent und bitten jedermann um Beiträge für die Archive mit der Einladung an das breite Publikum “Markiere deine Geschichte für die Welt.”[13] In Florenz brachten BürgerInnen 2014 anlässlich einer öffentlichen Ausstellung zum 70. Jahrestag der Beendigung der deutschen Okkupation[14] Dokumente aus ihren persönlichen Beständen und veröffentlichten sie unter Verwendung des MemorySharing-Projekts. Alte Dokumente von 1944 wurden gescannt und in heutige Straßenkarten der Stadt integriert. Soldaten aus Neuseeland werden darin direkt in Google Street View dargestellt.[15] Man kann die historische Bildquelle[16] verblassen lassen, um die aktuelle Aufnahme der Straße zu betrachten.

Könnten GeschichtswissenschafterInnen das Potential der digitalen Public History mit Historypin nutzen, eines Werkzeugs, das es einfach macht, auch schwierige Vergangenheiten nachträglich darzustellen? Alon Confino hat versucht, die unsichtbare Vergangenheit vor 1948 des palästinensischen Dorfs Tantura (Dor) im heutigen Israel zu rekonstruieren. Confino studierte Katasterkarten, Luftaufnahmen und Darstellungen von Palästinensern, die vor dem 22.-23. Mai 1948 aufgenommen wurden. Aber von NutzerInnen der sozialen Medien können nun auch Originaldokumente der palästinensischen Diaspora hinzugefügt werden: die Rekonstruktion palästinensischer Erinnerungen von 1948 müsste möglich sein.[17]

Public History als visuelles Narrativ

Inspiriert durch ein Foto von Michael Hughes (“Souvenirs” [18]) verschmelzen im Flickr-Projekt Looking into the Past Vergangenheit und Gegenwart zu einer einzigartigen Darstellung.[19] Dank der digitalen Technologien ist die Erstellung von “Geisterbildern zu Familiengeschichten” (“ghosting family pasts”) eine sehr populäre Methode geworden, um Erinnerungen wieder zu beleben. Das Verschmelzen von alten Fotos mit Aufnahmen aus der Gegenwart verkürzt die digitale Zeitlinie und aktiviert unterschiedliche Ausprägungen von Historizität in der Gegenwart.[20]

Das Past Present Project in Tumblr[21], das Familienbilder veröffentlicht, in denen Vergangenheit und Gegenwart überlappen, ist repräsentativ für viele andere Projekte auf der ganzen Welt.[22] Darstellungen, die mit dieser Technik der “Überlappung” die Vergangenheit von Orten verbildlichen, formen eine nostalgische Gegenwart, wie zum Beispiel die verschmolzenen Zeitlichkeiten des ungarischen Künstlers Zoltán Kerényi,[23] oder Hebe Robinsons nordnorwegische Echoes. In diesem Projekt fügt Robinson alte Familienfotos von einem Fischerdorf in den Lofoten, das nach dem 2. Weltkrieg aufgegeben wurde, in die heutige Landschaft ein.[24] Diese neue Abbildungen, manchmal rephotography[25] genannt, vereinen unterschiedliche Zeitschichten in einem einzigartigen Bild. Sogar Geisterbilder aus dem 1. Weltkrieg können in ein Vergangenheit-Gegenwart-Kontinuum eingebettet (“ghosted”) werden.[26] Das gleiche Verfahren wendet der russische Fotograf Sergey Larenkov in seinem Projekt Link to the Past mit Bildern aus dem 2. Weltkrieg an.[27] Der Autor einer Website über Krakau “sucht sehr alte Fotos der Stadt und nimmt neue von genau derselben Stelle auf, so dass seine LeserInnen vergleichen und sehen können, was sich verändert hat.”[28] Keith Jones, in seinem Projekt Liverpool then and now,[29] läßt uns “verschmolzene Schnappschüsse” (im Original: “blended shots”) entdecken: alte Schwarzweißaufnahmen verschmelzen mit aktuellen Farbaufnahmen.[30]

Vergangenheit/Gegenwart-Beziehungen in Fotos

Die italienische Fotographin Isabella Balena machte Aufnahmen der Ruinen der Linea Gotica, welche die Offensive der Alliierten von 1944 in Zentralitalien zum Stillstand brachte, 60 Jahre nach diesem Ereignis. Ihr Projekt Ci resta il nome, eine fotographische Reise durch Erinnerungen an den 2. Weltkrieg in Italien, ist ein gutes Beispiel für ein visuelles Narrativ von Public History.[31] Das Wichtige in Balenas systematischer Wiedergabe von Denkmälern und Spuren der gewalttätigen Vergangenheit ist die Sensibilisierung dafür, wie der Ort, an dem Mussolini im April 1945 erschossen wurde, sowohl von Präsentismus wie auch von Vergessenheit erzählt und offen für die Gegenwart und neue Zukünfte ist.

Aber Fotographie kann auch zeigen, dass die Gegenwart ihre Verbindung zur Vergangenheit verloren hat. Ein kompletter Verlust jeglicher Verbindung mit Geschichte wird von Serge Gruzinski mit dem Umschlagbild seines Buchs L’Histoire pour quoi faire? vorgeführt:[32] junge, postkoloniale Algerier spielen Fußball. Ihr Torhüter steht vor einem antiken römischen Bogen, ein Symbol der verlorenen Erinnerungen. Der Bogen bedeutet ihnen nichts. Statt dessen, im Kontext der heutigen Kampagnen des IS, vernichten islamistische Extremisten Erbstücke der Vergangenheit, sodass die Geschichte neu geschrieben und das Gedächtnis für immer gelöscht werden kann.[33]

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- François Hartog: Régimes d’historicité: présentisme et expériences du temps., Paris: Seuil, 2003 (Regimes of historicity: presentism and experiences of time, translated by Saskia Brown, New York: Columbia University Press, 2015.

- Serge Gruzinski: L’Histoire pour quoi faire?, Paris: Fayard, 2012.

- Serge Noiret: “Nulla sarà più come prima: considerazioni sul Digital Turn e le fonti fotografiche dal punto di vista della storiografia.” in Gian Piero Brunetta and Carlo Alberto Zotti Minici (eds.): La fotografia come fonte di storia, atti del convegno (Venezia, 4-6 ottobre 2012), Venezia, Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, 2014, pp.248-268.

Webressourcen

- 1940-1944 Firenze in guerra: http://www.firenzeinguerra.com (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015)

- Historypin – a global community collaborating around history: http://www.historypin.org (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015)

- Flickr Group “Looking Into the Past”: http://www.flickr.com/groups/lookingintothepast/ (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015)

____________________

[1] Andreas M. Kaplan, and Michael Haenlein, “Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media”, in Business Horizons, 53/1, 2010 pp. 59-68.

[2] Dario Miccoli studies how the Jewish diaspora from the Maghreb is today “reconnected” through the web and social media. See “Digital museums: narrating and preserving the history of Egyptian Jews on the Internet”, in E. Trevisan Semi, D. Miccoli and T. Parfitt (eds.), Memory and Ethnicity. Ethnic Museums in Israel and the Diaspora, Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2013, pp.195-222; “Les Juifs du Maroc, Internet et la construction d’une diaspora numérique”, in Expressions Maghrébines, 13/1, 2014, pp.75-94.

[3] André Gunthert: “Shared Images”, in Études photographiques, 24, novembre 2009, http://etudesphotographiques.revues.org/3436 (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015); “L’image conversationnelle”, in Études photographiques, 31, 2014, http://etudesphotographiques.revues.org/3387 (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015).

[4] Eine Liste der Länder, die nach den USA (2006) und Großbritannien (2007) eine Version von Got Talent ausstrahlten, findet sich in Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Got_Talent; siehe auch: America’s Got Talent (2006), http://www.nbc.com/americas-got-talent; La France a un incroyable talent (2006), http://www.m6.fr/emission-la_france_a_un_incroyable_talent/; Britain’s got talent http://www.itv.com/britainsgottalent; general information in Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Britain%27s_Got_Talent (Für alle letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015).

[5] Pierre Bourdieu, Luc Boltanski, Roger Castel and Philippe de Vendeuvre: Photography, a Middle-Brow Art, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990.

[6] Richard Chalfen, “La photo de famille et ses usages communicationnels”, Études photographiques, n. 32, 2015, http://etudesphotographiques.revues.org/3502 (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015).

[7] Jerome De Groote: “International Federation for Public History Plenary Address: On Genealogy”, in The Public Historian, Vol. 37, No. 3, August 2015, pp. 102-127, DOI: 10.1525/tph.2015.37.3.102 (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015).

[8] André Gunthert: “The consecration of the selfie”, in Études photographiques, 32, 2015, http://etudesphotographiques.revues.org/3537 (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015)

[9] Historypin in Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historypin (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015); see also Hunter Skipworth: Historypin turns Google Street View into a window on the past, June 21, 2010, The Telegraph, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/google/7854922/Historypin-turns-Google-Street-View-into-a-window-on-the-past.html (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015); Béat Brüsch: “L’histoire en noir et blanc”, in: Mots d’Image, http://www.motsdimages.ch/L-histoire-en-noir-et-blanc.html.

[10] “A global community collaborating around history […]”, http://www.historypin.com/ (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015). Historypin wurde von der gemeinnützigen Gesellschaft Shift mit Unterstützung von Google ins Leben gerufen und im Juli 2011 am Museum of the City of New York offiziell gestartet. Die Gesellschaft verfolgt das Ziel, “zu ermöglichen, daß Netzwerke von Menschen lokale Geschichte teilen und erkunden, neue Verbindungen aufbauen und soziale Isolation verringern.” Siehe Historypin, http://www.shiftdesign.org.uk/products/historypin/ (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015).

[11] Meg Foster: “Online and Plugged In? Public History and Historians in the Digital Age”, in Public History Review, Vol.21, 2014, pp. 1-19, http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/phrj/article/view/4295/4601 (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015)

[12] Kris Jarosik: “Primary Sources With Some Help from Historypin”, in The National Archives Education Updates, http://education.blogs.archives.gov/2014/12/16/primary-sources-on-history-pin/ (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015).

[13] NARA, http://www.archives.gov/social-media/historypin.html (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015).

[14] http://www.regione.toscana.it/-/1940-1944-firenze-in-guerra (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015); Filippo Macelloni and Lorenzo Garzella: MemorySharing a Firenze, http://www.firenzeinguerra.com/memorysharing/ (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015). Francesco Cavarocchi and Valeria Galimi: Firenze in Guerra, 1940-1944, Florence: Firenze University Press, 2014, pp. XXIV-XXV.

[15] Das historische Zentrum von Florenz auf einer Google-Karte mit neuen Dokumenten von 1944 ist jetzt verfügbar. Hier ein direkter Link mit geographischen Koordinaten:

https://www.historypin.org/map/#!/geo:43.789874,11.271481/zoom:13/date_from:1944-01-01/date_to:1944-12-31/ (Letzter Zugriff am 5.20.2015).

[16] Kaye, George Frederick, 1914-2004. Looking towards the Porta Romana in southern Florence, Italy, in World War II, http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22827427 (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015)

[17] Alon Confino : “Miracles and Snow in Palestine and Israel: Tantura, a History of 1948.”, in Israel Studies, vol. 17, n. 2, 2012, pp. 25-61, (photos are published on pages 44-55).

[18] https://www.flickr.com/photos/michael_hughes/sets/346406/ (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015).

[19] Ghosting the Past ist der Titel eines Bildes, das zwei Generationen einer Familie zeigt, wie sie eine Pause auf Capitol Hill einlegen. Wie ihre Großeltern besuchte die nächste Generation dasselbe “Reich der amerikanischen Erinnerung”. (Looking into the Past http://www.flickr.com/groups/lookingintothepast/ (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015)).

[20] François Hartog: Regimes of historicity: presentism and experiences of time (translated by Saskia Brown), New York: Columbia University Press, 2015.

[21] Christian Carollo’s Past Present Project in Tumblr, http://pastpresentproject.com; The Past Present Project in Instagram, https://instagram.com/sayhellotoamerica/; The Past Present Project in Facebook https://www.facebook.com/pastpresentproject (Für alle letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015).

[22] “Ich fragte mich”, sagte der Fotograph Christian Carollo, “was wäre, wenn ich die Fotos meines Großvaters 30 Jahre später replizieren könnte?” http://pastpresentproject.com/about (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015).

[23] 25 photos du passé se superposent avec le présent pour vous faire découvrir leurs histoires

http://soocurious.com/fr/25-photos-du-passe-se-superposent-avec-le-present-pour-vous-faire-decouvrir-leurs-histoires/ (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015)

[24] Hebe Robinson: Echoes, http://www.heberobinson.com/#mi=2&pt=1&pi=10000&s=0&p=1&a=0&at=0 (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015)

[25] Loïc Haÿ: Quand la rephotographie rencontre le numérique, https://tackk.com/rephotographie (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015)

[26] Pictured: Fascinating World War One photographs mixed with today’s modern landscapes, April 22, 2014, http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/world-war-one-photographs-mixed-3433146 (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015).

[27]Sergey Larenkov: Связь времен / Link to the Past, URL: http://sergey-larenkov.livejournal.com

[28] Die Fotos sind geteilt; die alte Schwarzweißaufnahme grenzt direkt an die neue in Farbe. Der Betrachter kann Teile oder die Gesamtheit von einem der zwei kombinierten Darstellungen löschen. (Kuba: Dawno temu w Krakowie, http://www.dawnotemuwkrakowie.pl/english/) (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015).

[29] Keith Jones: Liverpool Then and Now, https://www.flickr.com/photos/keithjones84/sets/72157632063149974/ (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015).

[30] Liverpool Then and Now, https://www.facebook.com/LiverpoolThenAndNow (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015)

[31] Isabella Balena: Ci resta il nome., Milano: Mazzotta, 2004 and http://isabalena.photoshelter.com/#!/about (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015).

[32] Serge Gruzinski: L’Histoire pour quoi faire?, Paris: Fayard, 2012, pp.21-24.

[33] Isis Video Claims Attack On Unesco Iraq World Heritage Site, https://youtu.be/iAWQHWU1H94 (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015).

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

© Khánh Hmoong: Citadel Gate, Huế 1968 12 March 2012 in: Looking into the Past, Vietnam, Flickr https://www.flickr.com/photos/hmoong/6976527765/in/gallery-jasonepowell-72157632522529341/ (Letzter Zugriff am 5.10.2015)

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Noiret, Serge: Narrative der digitalen Public History mit Fotografien. In: Public History Weekly 3 (2015) 31, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2015-4706.

Les médias sociaux sont “un groupe d’applications basées sur Internet qui reposent sur les fondements idéologiques et technologiques du Web 2.0, et qui permettent la création et l’échange de contenus générés par l’utilisateur.”[1] Ils facilitent les différentes formes de communication dans la toile entre individus et communautés. Ils favorisent une discussion commune et permettent de partager les traces du passé. Les communautés locales qui s’engagent dans l’étude de leur passé, avec ou sans médiation professionnelle, utilisent les pratiques du Web 2.0. De nouveaux contacts virtuels peuvent d’ailleurs être construits lorsque des communautés ne sont plus présentes dans un espace physique.[2]

Tout le monde a du talent: les connaissances générées par les utilisateurs

Si les médias sociaux permettent aux communautés dispersées de se reconnecter en ligne et de partager leurs souvenirs, comprendre aujourd’hui comment le grand public les utilise et joue avec l’histoire, nous apprend beaucoup de choses sur l’importance du passé dans notre présent.[3]

Tout le monde tente de se promouvoir. Ce que l’on appelle “Got Talent” (La France a du talent)[4] sont les émissions de télévision les plus suivies dans le monde entier parce qu’elles choisissent de montrer des gens inconnus et de les connecter avec un public. Ces spectacles révèlent des compétences inexprimées et des capacités créatives comme le font aussi les médias sociaux en ligne qui offrent une production participative de connaissances autour du passé. Comme les émissions de télévision Got Talent, les médias sociaux permettent à différents publics de promouvoir les individus, l’histoire de leur famille et celle de leur communauté.

Le sociologue Pierre Bourdieu a défini la répétition systématique de photographies de famille semblables, comme un phénomène emblématiques du comportement et des cultures populaires.[5] Partager différentes photos de générations diverses d’une même famille dans les médias sociaux permet de préciser les contours des mémoires collectives.[6] D’autre part, la requête populaire envers la généalogie,[7] ne fait qu’effleurer la surface des grands événements de l’histoire et est souvent déconnectée de la “grande histoire” et des contextes plus larges. Mais la photographie, dans les médias sociaux, décrit les comportements populaires – les “selfies” aujourd’hui[8] – et, grâce aux technologies du web sémantique (Linked Data), à Google Maps et à Google Street View, elle permet d’ajouter une dimension spatiale et temporelle aux mémoires individuelles.

Épinglez vos images avec Historypin, une machine du temps numérique

“Historypin est une machine du temps numérique qui crée une nouvelle façon pour le monde de voir et de partager l’histoire”.[9] Le web de données et le web sémantique connectent des sources primaires numériques à la géographie.[10] De vieilles photos peuvent être “épinglées” dans le présent: le passé familial peut ainsi être revisité aujourd’hui. Les établissements du patrimoine, mais aussi des gens ordinaires, organisent ainsi de nouvelles formes de narration parce que la technologie est facile à utiliser. Les historiens publics prennent Historypin très au sérieux pour travailler avec des communautés spécifiques.[11] Grâce à Historypin, les archives nationales américaines (NARA) sont maintenant partout “à l’extérieur du bâtiment” et dans l’espace virtuel ![12] Les archivistes sollicitent la contribution de tout le monde pour compléter les archives historiques invitant le grand public à “épingler votre histoire dans celle du monde.”[13]

A Florence, lors d’une exposition publique (2014) commémorant le 70e anniversaire de la fin de l’occupation allemande,[14] le projet MemorySharing, a permis aux citoyens d’apporter leurs propres documents sur place. Des documents datant de 1944 ont ainsi été numérisés et inclus dans les cartes géographiques actuelles de Florence.[15] Des soldats Néo-Zélandais sont représentés grâce à Google Street View directement sur les cartes d’aujourd’hui. Vous pouvez estomper la vielle image pour découvrir la rue contemporaine.[16]

Les historiens académiques pourraient-ils également utiliser les potentialités de l’histoire publique numérique avec Historypin, un outil qui permettrait de reconstruire facilement même un passé difficile? Alon Confino a essayé de reconstituer une histoire invisible: la présence palestinienne avant 1948 à Tantura, Dor en Israël aujourd’hui. Confino a étudié les plans cadastraux, les photographies aériennes et des images d’avant les 22-23 mai 1948. Mais le contenu généré par l’utilisateur à travers les médias sociaux permettrait certainement d’ajouter des documents originaux de la diaspora palestinienne: une reconstitution des mémoires palestiniennes à propos de leurs vie à Tantoura avant les événements de 1948, devrait ainsi être possible.[17]

Récits visuels d’histoire publique

Inspiré par le projet “Souvenirs” du photographe Michael Hughes dans Flickr,[18] Looking into the Past (Regarder le passé), permet de confondre passé et présent dans une seule photographie.[19] Montrer les “fantômes du passé familial”, grâce aux technologies du numérique, est très populaire pour ressusciter les souvenirs ensevelis. La fusion de vieilles photos et d’images récentes raccourcit le calendrier et permet d’activer différents régimes d’historicité dans le présent.[20]

Ainsi, le projet Past Present dans Tumblr,[21] est emblématique de nombreux autres projets au niveau mondial. Il publie des photos de famille où le passé et le présent se chevauchent.[22] Des images qui montrent l’ancienneté des lieux, nous parlent avec nostalgie dans le présent : des vues urbaines passées et actuelles sont fusionnées en une seule image par l’artiste hongrois Zoltán Kerényi;[23] le projet Echoes de Hebe Robinson place de vieilles photos de famille d’un village de pêcheurs des Lofoten, au Nord de la Norvège, abandonné après la seconde guerre mondiale, dans le paysage d’aujourd’hui.[24] Parfois appelé rephotographies,[25] ces nouvelles images contiennent différentes strates temporelles en une image unique. Même les images de la Première Guerre Mondiale en noir et blanc, sont montrées aujourd’hui dans un continuum passé-présent;[26] celles du photographe russe Sergey Larenkov dans Link to the Past le font également pour la seconde guerre.[27] L’auteur d’un site Web sur Cracovie “cherche de très vieilles photos de la ville et prend de nouvelles photos au même endroit, afin que ses lecteurs puissent comparer et voir ce qui a changé”.[28] Keith Jones dans le projet Liverpool Then and Now,[29] nous fait découvrir des photos mixtes, faites de vieilles images en noir et blanc fusionnées avec celles d’aujourd’hui en couleur.[30]

La relation passé-présent dans les photographies

La photographe italienne Isabella Balena, a photographié soixante ans plus tard, les ruines de la “Ligne gothique” qui a arrêté l’offensive alliée en 1944 dans le centre de l’Italie. Ci Resta il nome, (Seul le nom a survécu) est un voyage photographique dans la mémoire de la Seconde Guerre mondiale en Italie. Ce projet est un bon exemple de récit visuel d’histoire publique.[31] Ce qui est important dans la reproduction systématique qu’a faite Balena des monuments et des vestiges d’un passé violent, c’est de montrer comment, l’endroit où Mussolini a été passé par les armes en avril 1945, parle à la fois de présentisme et d’oubli; ce lieu historique reste ouvert au présent et au futur.

Mais la photographie peut aussi montrer que le présent a perdu son rapport avec le passé. Une déconnexion totale avec l’histoire est ce que montre Serge Gruzinski publiant la photo de couverture de son livre “L’Histoire pour quoi faire?”[32]: De jeunes algériens jouent au football dans la société postcoloniale. Leur gardien de but s’est placé devant un ancien arc romain, symbole d’une mémoire perdue. L’Arc ne veut rien dire pour eux. Au lieu de cela, lors des campagnes de DAESH d’aujourd’hui, les extrémistes de l’état islamique détruisent le patrimoine archéologique afin que l’histoire puisse être réécrite et la mémoire du passé gommée pour toujours.[33]

____________________

Littérature

- François Hartog: Régimes d’historicité: présentisme et expériences du temps., Paris: Seuil, 2003 (Regimes of historicity: presentism and experiences of time, translated by Saskia Brown, New York: Columbia University Press, 2015.

- Serge Gruzinski: L’Histoire pour quoi faire?, Paris: Fayard, 2012.

- Serge Noiret: “Nulla sarà più come prima: considerazioni sul Digital Turn e le fonti fotografiche dal punto di vista della storiografia.” in Gian Piero Brunetta and Carlo Alberto Zotti Minici (eds.): La fotografia come fonte di storia, atti del convegno (Venezia, 4-6 ottobre 2012), Venezia, Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, 2014, pp.248-268.

Liens externe

- 1940-1944 Firenze in guerra: http://www.firenzeinguerra.com (dernier accès 5.10.2015)

- Historypin – a global community collaborating around history: http://www.historypin.org (dernier accès 5.10.2015)

- Flickr Group “Looking Into the Past”: http://www.flickr.com/groups/lookingintothepast/ (dernier accès 5.10.2015)

____________________

[1] Andreas M. Kaplan, and Michael Haenlein, “Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media”, dans Business Horizons, 53/1, 2010 pp. 59-68.

[2] Dario Miccoli a étudié la diaspora juive du Maghreb. Il montre que la mémoire d’un passé collectif peut être reconstruite dans la toile et avec les medias sociaux. Voir “Digital museums: narrating and preserving the history of Egyptian Jews on the Internet”, dans E. Trevisan Semi, D. Miccoli and T. Parfitt (eds.), Memory and Ethnicity. Ethnic Museums in Israel and the Diaspora, Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2013, pp.195-222; “Les Juifs du Maroc, Internet et la construction d’une diaspora numérique”, dans Expressions Maghrébines, 13/1, 2014, pp.75-94.

[3] André Gunthert: “Shared Images”, dans Études photographiques, 24, novembre 2009, http://etudesphotographiques.revues.org/3436 (dernier accès 5.10.2015); “L’image conversationnelle”, dans Études photographiques, 31, 2014, http://etudesphotographiques.revues.org/3387 (dernier accès 5.10.2015).

[4] La liste des pays qui ont offerts, après les USA en 2006 et la GB en 2007, une copie de l’émission Got Talent est disponible dans Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Got_Talent; America’s Got Talent (2006), http://www.nbc.com/americas-got-talent; La France a un incroyable talent (2006), http://www.m6.fr/emission-la_france_a_un_incroyable_talent/; Britain’s got talent http://www.itv.com/britainsgottalent; general information in Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Britain%27s_Got_Talent (pour tous dernier accès 5.10.2015).

[5] Pierre Bourdieu, Luc Boltanski, Roger Castel and Philippe de Vendeuvre: Photography, a Middle-Brow Art, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990.

[6] Richard Chalfen, “La photo de famille et ses usages communicationnels”, Études photographiques, n. 32, 2015, http://etudesphotographiques.revues.org/3502 (dernier accès 5.10.2015).

[7] Jerome De Groote: “International Federation for Public History Plenary Address: On Genealogy”, dans The Public Historian, Vol. 37, No. 3, August 2015, pp. 102-127, DOI: 10.1525/tph.2015.37.3.102 (dernier accès 5.10.2015).

[8] André Gunthert: “The consecration of the selfie”, dans Études photographiques, 32, 2015, http://etudesphotographiques.revues.org/3537 (dernier accès 5.10.2015)

[9] Historypin in Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historypin (dernier accès 5.10.2015); voir également de Hunter Skipworth: Historypin turns Google Street View into a window on the past, June 21, 2010, The Telegraph, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/google/7854922/Historypin-turns-Google-Street-View-into-a-window-on-the-past.html (dernier accès 5.10.2015); Beat Brüsch: “L’histoire en noir et blanc”, dans: Mots d’Image, http://www.motsdimages.ch/L-histoire-en-noir-et-blanc.html

[10] “A global community collaborating around history […]”, http://www.historypin.com/ (dernier accès 5.10.2015). Historypin a été créé par une société sans but lucratif appelée Shift avec le soutien de Google. Elle a été lance au Musée de la Vile de New York en juillet 2011. “Permettre l’activation de réseaux pour partager et explorer l’histoire locale, créer de nouveaux liens entre individues et réduire l’isolement social” était le but déclaré de cette companie. Voir Historypin, http://www.shiftdesign.org.uk/products/historypin/ (dernier accès 5.10.2015).

[11] Meg Foster: “Online and Plugged In? Public History and Historians in the Digital Age”, dans Public History Review, Vol.21, 2014, pp. 1-19, http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/phrj/article/view/4295/4601 (dernier accès 5.10.2015)

[12] Kris Jarosik: “Primary Sources With Some Help from Historypin”, dans The National Archives Education Updates, http://education.blogs.archives.gov/2014/12/16/primary-sources-on-history-pin/ (dernier accès 5.10.2015).

[13] NARA, http://www.archives.gov/social-media/historypin.html (dernier accès 5.10.2015).

[14] http://www.regione.toscana.it/-/1940-1944-firenze-in-guerra (dernier accès 5.10.2015); Filippo Macelloni and Lorenzo Garzella: MemorySharing a Firenze, http://www.firenzeinguerra.com/memorysharing/ (dernier accès 5.10.2015). Francesco Cavarocchi and Valeria Galimi: Firenze in Guerra, 1940-1944, Florence: Firenze University Press, 2014, pp. XXIV-XXV.

[15] Le centre historique de Florence est maintenant disponible sur une carte Google avec des documents datants de 1944 incorporés. Ceci est le lien direct aux coordonnées géographiques de l’image:

https://www.historypin.org/map/#!/geo:43.789874,11.271481/zoom:13/date_from:1944-01-01/date_to:1944-12-31/ (dernier accès 5.20.2015).

[16] Kaye, George Frederick, 1914-2004. Looking towards the Porta Romana in southern Florence, Italy, in World War II, http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22827427 (dernier accès 5.10.2015)

[17] Alon Confino : “Miracles and Snow in Palestine and Israel: Tantura, a History of 1948.”, dans Israel Studies, vol. 17, n. 2, 2012, pp. 25-61, (photos are published on pages 44-55).

[18] https://www.flickr.com/photos/michael_hughes/sets/346406/ (dernier accès 5.10.2015).

[19] Ghosting the Past est le titre d’une photo montrant deux générations de la même famille en pause sur Capitol Hill. Comme leurs grands-parents, la génération suivante a visité le même “lieu de mémoire américain”. (Looking into the Past http://www.flickr.com/groups/lookingintothepast/ (dernier accès 5.10.2015)).

[20] François Hartog: Regimes of historicity: presentism and experiences of time (translated by Saskia Brown), New York: Columbia University Press, 2015.

[21] Christian Carollo’s Past Present Project in Tumblr, http://pastpresentproject.com; The Past Present Project in Instagram, https://instagram.com/sayhellotoamerica/; The Past Present Project in Facebook https://www.facebook.com/pastpresentproject (pour tous dernier accès 5.10.2015).

[22] “Je me demandais”, écrit le photographe Christian Carole, “si je pouvais reproduire une photo de mon grand-père 30 ans plus tard.” http://pastpresentproject.com/about (dernier accès 5.10.2015).

[23] 25 photos du passé se superposent avec le présent pour vous faire découvrir leurs histoires

http://soocurious.com/fr/25-photos-du-passe-se-superposent-avec-le-present-pour-vous-faire-decouvrir-leurs-histoires/ (dernier accès 5.10.2015)

[24] Hebe Robinson: Echoes, http://www.heberobinson.com/#mi=2&pt=1&pi=10000&s=0&p=1&a=0&at=0 (dernier accès 5.10.2015)

[25] Loïc Haÿ: Quand la rephotographie rencontre le numérique, https://tackk.com/rephotographie (dernier accès 5.10.2015)

[26] Pictured: Fascinating World War One photographs mixed with today’s modern landscapes, April 22, 2014, http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/world-war-one-photographs-mixed-3433146 (dernier accès 5.10.2015).

[27]Sergey Larenkov: Связь времен / Link to the Past, URL: http://sergey-larenkov.livejournal.com

[28] Les photos sont divisées, l’ancienne image en noir et blanc à côté de la nouvelle en couleur. Le lecteur peut annuler une partie ou l’entièreté de l’une des deux images combines dans le même espace. (Kuba: Dawno temu w Krakowie, http://www.dawnotemuwkrakowie.pl/english/) (dernier accès 5.10.2015).

[29] Keith Jones: Liverpool Then and Now, https://www.flickr.com/photos/keithjones84/sets/72157632063149974/ (dernier accès 5.10.2015).

[30] Liverpool Then and Now, https://www.facebook.com/LiverpoolThenAndNow (dernier accès 5.10.2015)

[31] Isabella Balena: Ci resta il nome., Milano: Mazzotta, 2004 and http://isabalena.photoshelter.com/#!/about (dernier accès 5.10.2015).

[32] Serge Gruzinski: L’Histoire pour quoi faire?, Paris: Fayard, 2012, pp.21-24.

[33] Isis Video Claims Attack On Unesco Iraq World Heritage Site, https://youtu.be/iAWQHWU1H94 (dernier accès 5.10.2015).

____________________

Crédits illustration

© Khánh Hmoong: Citadel Gate, Huế 1968 12 March 2012 dans: Looking into the Past, Vietnam, Flickr https://www.flickr.com/photos/hmoong/6976527765/in/gallery-jasonepowell-72157632522529341/ (dernier accès 5.10.2015).

Citation recommandée

Noiret, Serge: Ecrire une histoire publique numérique avec des photographies. Dans: Public History Weekly 3 (2015) 31, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2015-4706.

Copyright (c) 2015 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact: elise.wintz (at) degruyter.com.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 3 (2015) 31

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2015-4706

Tags: Digital Change (Digitaler Wandel), Historical Sources (Quellen), Language: French, Photographs (Fotografien), Public History

Very interesting, Serge! I would like to see more uses of Historypin, indeed. It is not a very new tool, and I am surprised how it is underused by academic historians. I wrote about it on 2012 (here: http://www.infonet.com.br/educacao/ler.asp?id=138124) and didn’t get any feedback or comments from my Brazilian colleagues.

Also, this reading reminds me of the testimonies of @Rio450’s participants about how their experience with the pictures of the city Rio de Janeiro to the project were connected with their own everyday life. How they recognize it shapes collective memories and how they were proud of it, feeling, somehow, linked to the “big history”, while they expect those pictures could be, somewhat, a source for historians in the future. I would like to see further interpretations on that pictures afterwards. There are a lot of things on the table to discuss: commemoration, collective memory, narrativity, digital storytelling, historicity, public uses of the past.

Merci Serge pour cet article fort intéressant avec ses exemples et références vers des expériences multiples.

À propos des projets qui rapprochent des photos anciennes et des photos modernes, je crois qu’il faut distinguer au moins trois types de montages: la juxtaposition d’un cliché ancien et d’un cliché moderne (Rephotography, Then and Now) – pratique en général documentaire dont on peut retracer l’histoire depuis la fin du 19ème siècle, la fusion des deux clichés (Ghosts, Looking into the Past) et l’insertion d’un cliché ancien superposé à une partie d’un cliché moderne (Past in Present) qui visent à créer un effet esthétique ou émotionnel. La terminologie est encore fluctuante mais il s’agit là de pratiques utilisées à des fins différentes et qui sont apparues à des époques différentes. Par ailleurs, les deux derniers procédés reposent fondamentalement sur une convention culturelle qui associe le passé au noir et blanc et le présent à la couleur. Ils fonctionnent beaucoup moins bien avec un cliché ancien et un cliché récent qui sont tous deux en couleur. Et si l’on inverse la technique en fusionnant une photo ancienne en couleurs et une photo récente en noir et blanc, l’effet devient curieux car c’est le présent qui semble projeté dans le passé.

Je me permets de renvoyer pour plus de précisions à mon article de 2012 “Re-photographie et effet de présent”, cf. http://dejavu.hypotheses.org/1268 (les commentaires de l’article mentionnent aussi d’autres projets très intéressants).

[Die deutsche Übersetzung findet sich unter dem englischen Text.]

Merci beaucoup pour cet article qui aborde un thème bien intéressant. Contrairement à l’usage des photos ni les potentiels ni les problèmes particuliers des images numérisées ont été discutés dans la perspective de la didactique de l’histoire. Des vieilles photos numérisées et la façon de les publier et commenter dans les médias sociaux n’est pas uniquement une question pour l’histoire publique mais aussi pour l’enseignement de l’histoire au collège et au lycée. De travailler en classe avec des photos numérisées de leurs communautés ou familles permettent aux élèves une approche bien plus compétente et critique que celle que nous trouvons à l’heure actuelle dans de milliers de groupes locaux dans les médias sociaux où l’on partage et commente des vieilles photos des albums de famille en tant qu’assurance mutuelle que tout allait mieux dans le passé.

Par le développement d’une application web spécialement pour l’enseignement de l’histoire, nous avons essayé de combiner l’intérêt pour l’histoire que les photos historiques peuvent susciter, la facilité de leur usage par la technologie et l’enseignement exploratoire pour faire des recherches locales en utilisant le signal GPS. L’application « App in die Geschichte » (jusqu’à maintenant seulement disponible en allemand mais programmée de manière à en tirer facilement des copies dans d’autres langues) peut être utilisée dans tous les navigateurs et qui est gratuit, sans publicité et code source ouvert : http://app-in-die-geschichte.de/

On peut trouver des informations sur le développement de l’application, des réflexions didactiques et méthodiques pour l’utilisation en classe (également en allemand) ici : https://geschichtsunterricht.wordpress.com/2014/04/24/mobiles-geschichtslernen-app-in-die-geschichte-online/

Cette application représente une première tentative de développer des outils digitaux spécialement pour l’enseignement de l’histoire. Elle comporte à peu près 80.000 photos numérisées surtout des fonds des Archives Fédérales d’Allemagne. Elle offre trois outils pour travailler avec des photos numérisées en classe d’histoire :

1) Dans le « mapping game » (jeu à créer des cartes), les élèves doivent chercher la perspective des photos (aussi peintures et dessins) historiques dans le paysage urbain actuel. Il faut trouver la bonne place, en prendre une photo qui imite la perspective de l’image historique et la partager dans le groupe d’élèves. Par cette fonction, des explorations indépendantes de la communauté par les élèves sont documentées par leurs photos prises. La comparaison des vieilles représentations avec les nouvelles photos peut être le point de départ pour apprendre plus et faire des recherches approfondies sur l’histoire de la communauté ou du quotidien.

2) Dans le « tagging game » (jeu des mots-clés) les élèves doivent observer des images de très près et les décrire par mots-clés. Chaque image à laquelle 5 mots-clés corrects sont attribuée change de catégorie et les élèves jouent au « Taboo » : Les mots-clés existants sont donnés et il faut trouver d’autres pour décrire l’image de manière plus détaillée. Pour chaque mot-clé correct, on reçoit normalement un point, comme c’est plus difficile dans le « Taboo » on reçoit 5 point. Ce jeu permet aux élèves d’entraîner l’observation et l’analyse des images.

3) Enfin, les utilisateurs peuvent compléter les « archives » de l’appli par d’autres textes, images ou vidéos. Pour combiner tout ce matériel, les élèves créent des lignes du temps multimédia et, par là, des nouvelles narrations. En plus d’une ligne du temps chronologique, on peut lier le matériel avec une date et un lieu précis pour le localiser sur une carte qui combine la dimension spatiale et temporelle.

Les premières expériences avec l’usage de l’appli dans les cours d’histoire ont montré des effets motivants parmi la plupart des élèves, surtout parmi les jeunes dans les premières années du collège. Les lycéens ont utilisé les fonctions d’une autre manière mais ils en ont aussi profité, par exemple dans la préparation des examens du bac.

IL faut encore plus d’expériences pour savoir s’il s’agit d’un effet de nouveauté. Finalement, il me paraît important de souligner qu’aucun des trois outils représente un gagdet purement technologique ni une fin en soi mais qu’il faut une réflexion didactique et méthodique pour un usage judicieux dans l’enseignement de l’histoire, par exemple pour aborder un nouveau thème ou pour la fixation et la présentation des résultats du travail d’élèves.

———————————————————–

Vielen Dank für diesen Beitrag, der ein interessantes Thema eröffnet. Im Gegensatz zum Umgang mit Fotos sind die besonderen Chancen und Probleme digitalisierter Bilder bislang in der Geschichtsdidaktik noch nicht breit diskutiert worden. Alte Fotos, die digitalisiert wurden, und der Umgang mit ihnen sind nicht nur eine Frage für Public History, sondern bieten auch Chancen für historisches Lernen. Mit digitalisierten Fotos aus der eigenen Gemeinde oder Familie im Unterricht zu arbeiten, kann die SchülerInnen in ihrem Alltag außerhalb der Schule zu einem kompetenteren und kritischeren Umgang mit solchen Zeugnissen befähigen, als wir ihn aktuell in zahlreichen Heimatgeschichtsgruppen in sozialen Netzwerken erleben, wo zur gegenseitigen Selbstvergewisserung, dass früher alles besser und schöner gewesen zu sein scheint, Fotos aus der Geschichte der eigenen Gemeinde und Familie geteilt und kommentiert werden.

Das Interesse an Geschichte, das historische Fotos wecken können, die Möglichkeiten der einfachen Bereitstellung digitaler Bilder sowie die Verknüpfung mit entdeckendem Lernen, das lokal und mittels GPS-Signal ortsbasiert ist, haben wir versucht, für den schulischen Geschichtsunterricht fruchtbar zu machen. Dazu haben wir die “App in die Geschichte” als Open Source-WebApp entwickelt, die über jeden Browser kosten- und werbefrei unter folgender Adresse verfügbar ist: http://app-in-die-geschichte.de/

Ein Überblick mit Informationen zur GeschichtsApp sowie eine Einführung in ihre Nutzung mit didaktischen und methodischen Überlegungen, die unten im Beitrag verlinkt sind, findet sich hier: https://geschichtsunterricht.wordpress.com/2014/04/24/mobiles-geschichtslernen-app-in-die-geschichte-online/

Die GeschichtsApp ist ein erster Versuch, spezielle digitale Werkzeuge für den Geschichtsunterricht zu entwickeln. Sie enthält fast 80.000 digitalisierte Bilder und bietet drei Werkzeuge zum historischen Lernen mit digitalisierten Fotos, vor allem aus den Beständen des Bundesarchivs.

1) Im Mapping Game sind die Lernenden aufgefordert, historische Fotos oder Gemälde im heutigen Stadt- und Landschaftsbild wiederzufinden. Sie suchen den heutigen Ort auf, machen dort ein Foto aus derselben Perspektive, wie sie im historischen Bild vorgegeben ist, und laden dieses in ihre Lerngruppe hoch. Dadurch sind selbstständige Ortserkundungen möglich, die mit eigenen Fotos dokumentiert werden, und im Anschluss den Ausgangspunkt für das Lernen in den Bereichen Stadt- und Alltagsgeschichte bilden können.

2) Im Tagging Game betrachten die Lernenden die Bilder genau und beschreiben sie anhand von Schlagworten. Hat ein Bild bereits fünf, auf diese Weise kollaborativ vergebene Schlagworte, erscheint es nur noch im “Tabu-Spiel”. Nun werden die bereits existierenden Schlagworte angezeigt und dürfen nicht mehr eingegeben werden. Finden Lernende nun weitere korrekte Schlagworte, gibt es für jedes ergänzende Schlagwort jeweils 5 Punkten statt 1 Punkt bei den einfachen Schlagworten. Dieses Spiel schult die genaue Betrachtung und Analyse von Bildern.

3) Die im “digitalen Archiv” vorhandenen Digitalisate können um andere Texte, Bilder und Videos ergänzt werden. Im Zeitleisten-Modus können die verschiedenen Materialien zu multimedialen Zeitleisten in einer Narration zusammengefügt werden, dabei besteht neben der klassisch chronologischen Zeitleiste auch die Möglichkeit die verschiedenen Materialien chronologisch zu ordnen und mit einer digitalen Karte zu verknüpfen.

Die ersten Unterrichtsversuche haben gezeigt, dass diese Angebote gerade bei jüngeren SchülerInnen motivierend wirken. Inwieweit es sich hierbei eventuell nur um einen “Neuigkeitseffekt” handelt, ist noch zu prüfen. Wichtig ist, dass keines der drei Werkzeuge reine digitale Spielerei oder nur Selbstzweck ist, sondern didaktisch reflektiert sinnvoll eingesetzt werden muss, z.B. zum Einstieg in ein neues Thema oder zur Ergebnissicherung.