Abstract:

Local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander published histories arguably remain underrepresented by first nations’ authors. In her article, Norman addresses the local history of the Aboriginal Land Council in a small town in rural Australia, Wee Waa (situated 565 kilometres northwest of Australia’s largest city, Sydney). This is the land of the Kamilaroi people and means place for fire or fire for roasting, and 16.8% (or, 350) of the town’s population identify as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander. Here, Norman examines the benefits of Aboriginal land restitution as managed through Local Aboriginal Land councils.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-18712

Languages: English

Writing about the centrality of land in NSW Aboriginal activism, historian Heather Goodall (1996) crafted a generous and sympathetic account of Aboriginal determination for land justice up until the ‘Tent Embassy’ protest in 1972.[1] Continuing this linear narrative, I wrote about the government response to this long-standing demand with the passing of the 1983 NSW Aboriginal land rights laws in 1983.[2] This work explored how the state responded to and crafted those ambitions; and how modern rule came to be exercised through and beyond Aboriginal citizens.

Emerging Central Themes

More recently, I have been researching the benefits of Aboriginal land restitution in NSW which explores how the organisations, known as Local Aboriginal Land Councils (LALCs) – of which there are 120 across NSW, in managing their newly acquired land assets, contest or affirm development discourse.

One central theme emerging from this research is how Aboriginal custodians have been focused on the work of their history. This incredible labour that I have observed at every field site I have visited is made possible by recognition of rights and interests in land and thus reveals a new chapter in the understanding of Aboriginal land and history. Turning to this labour, I detail here two examples, both come from Wee Waa – a small town on the flat grasslands country of north western NSW.

What emerges from the field work is the work of Aboriginal communities engaged in documenting their own history to hold the past, communicate across generations, create belonging, sustain community futures and know themselves. These processes of documenting and remembering Aboriginal stories of the past are less concerned with the state and settler hostility and unburdened by categorising time; the ‘old people’[3] or ‘1788’ appear irrelevant in the enthusiasm for living social and cultural history; not confined to the ‘fixed in time’ histories called upon in Native Title litigation or the debates among historians and their detractors over method and evidence or the moral weight in the national story of such accounts.

Academic Discourse

Once the purview of anthropological inquiry interested in the ‘other side of the frontier’ less contaminated by settlers that, with misplaced confidence, asserted knowledge of Indigenous worlds, over the last half-century, historians and others, challenged to address the ‘silence’ of their disciplines have contributed an enormous body of work of their own.[4]

In public and academic history spheres Aboriginal experiences from the ‘other side’ of the frontier have underpinned social and cultural change, underpinned social justice claims of the state, challenged accepted historiography, recast national narratives from peaceful settlement to one of violent conflict between colonial settlers and Aboriginal people, and celebrated narratives of resistance and survival. Yet deeply unsatisfactory notions of Aboriginal history in current academic discourse continue.

Aboriginal Voices

Aboriginal activism and creative practice, often differing in style and tone to academic discourse that ranges from poetry, street theatre, novels, music, biographies and stage plays, perform themes of political history as a process of renegotiating power and reimagining identities and futures.[5] Together, scientists, historians and traditional owners utilise new sources and methods to tell stories of the past stretched over much longer timeframes. And the return of Ancestral Remains and objects held in collecting institutions insist on connections unburdened by time or ‘tradition’.

Challenges and Provocations

The 2017 national gathering that culminated in the Uluru Statement from the Heart – took a less than expected turn: truth-telling about our history emerged as a key priority.[6] The call for truth telling, or some version of it, is a long-standing aspiration in the negotiation of a ‘rightful place in the nation’.[7] The National Reconciliation movement, beginning in 1990, listed greater awareness of Indigenous history and culture and a ‘shared sense of history’ as leading priorities; the recommendations of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (1991) references ‘history’ 26 times and the Bringing Them Home Report (1996) references ‘history’ 22 times.[8]

Aboriginal Land Estate and History

My field work reveals a different framework for narrating the past. Whereas earlier studies of land rights focused on Aboriginal politics and state responses, instead what emerges here is that having land enables stories and memories of place that are less settler worlds and logic focused.[9] These approaches suggest a different framework for narrating the past that are less naive renderings of survival, nor stripped of consciousness of the weight of the past and its power to define the present, nor are they preoccupied with ‘speaking back’ to the dominant historical and anthropological discourses. Rather, the labour Aboriginal communities are committing is to tell stories of people and places that are important to them. In this short entry, I canvas some of those approaches to local level Aboriginal specificity and consider how this work offers a different framework for thinking about the purpose, politics and poetics of Aboriginal history.

The first example I highlight is the recent successful heritage listing of the Waterloo Creek massacre site. The Waterloo Creek massacre of a group of Gamilaraay / Gomeroi people occurred on the grasslands and plains country of southwest Moree on January 26 1838. Commencing more than a decade ago, three LALCs (Narrabri, Wee Waa and Moree) banded together, in partnership with two bordering shire councils, to have the Waterloo Creek massacre place listed as a heritage site. At a recent discussion of the successful heritage listing, LALC representatives talked about the place; they shared photos from their recent site survey – grinding tools, blades and scar trees that continued to yield on this intensively farmed landscape and reflected on the significance of the heritage listing. Gomeroi man Steven Booby and Wee Waa LALC chairperson Clifford Toomey spoke about the significance of the site; as the quotes at the opening of this post illustrate, they are interested in being on this site, of adding new interpretations and honouring the past. They have thought about this for many years and their interest, through the heritage listing and the associated authority they will now hold over the site, to create space for dialogue and for healing. Of this heritage listing, both of these men emphasise the possibility of the site to engage narratives of the past, the present and for future generations.

The second example is the work of Wee Waa LALC and community to document and commemorate an Aboriginal cotton chipping camp that formed in the 1960s, known as Tulladunna. Tulladunna was an Aboriginal camp that sprung up in response to the seasonal demand for labour. It is also a site where political campaigns for Aboriginal wage justice, deaths in custody, racism and provision of basic services played out.

A documentary about community narratives of this place is available here:

What emerges in this example is community interest and commitment to recording shared stories of people and place. The work to commemorate the Aboriginal cotton chipping camp is undertaken by Aboriginal people who, now as adults, wanted their shared memories of this place to be known for themselves and for younger generations. They each explained the joy and preciousness of being together and the pride of survival is foregrounded alongside the hardships. As Colleen Combo recalls, ‘it was a simple life, a good life but also a hard one too’ and of living in tents, where you ‘always had no bedding’ and so ‘you all had to squeeze and huddle together’.

John Morris, who recalled with delight his memories of cotton chipping as a kid, spoke to the assembled primary children at the day celebrating the signage at Tulladunna and its future. To the assembled school children, he asked: any of you children ever been to the Gold Coast, been to Dreamworld? The children squinting into the sun, wondering where he was going with his question, raised their arms a little reluctantly. Morris replied: That’s what it was like for us coming here. It was a dream. Cos we come from something harder. We came from where there was no benefits, no hand-outs. We had to work. Sitting behind the children, I imagined their alarm and disbelief as they surveyed the now dry and broken river. John Morris says, ‘I was ten years old [working] ten hours a day for ten dollars. We thought we were millionaires … we had a lot of memories here’.

Helen Wenner, who you hear from in the documentary, says of her Murray Family, ‘Our family used to live, where you come in under the bridge, the sign there that’s got “Murrays”. It’s a big gum tree. There’s 12 of us in our family and we lived in a tent, with dirt floors, no brooms, used a tree to rake around our campsite and to me it was fond memories living on Tulladunna’.

Sharing the Past

Aboriginal people have a strong sense and consciousness of holding and sharing stories of the past, of the practice of history in order to survive now and sustain future generations in settled spaces. Where ‘erasure’ has been the focus of state ambitions and powerfully explains settler logic, the work of Aboriginal people on their own shared history – of places and community life, restoring grieving landscapes, that is enabled by restituted land and polity, reject this erasure. Having land creates the possibility to speak with confidence, and joy and preciousness about the past. In these too brief examples, I observe ‘living history’ of rich Aboriginal social worlds that are held gently with love and affection and honesty and with dedication to future generations. Across NSW many LALCs and communities are engaged in the practice of history: restoring graves, signage on old missions, returning Ancestors to Country, addressing the violent grief of the past through memorialisation and landscape care. The restituted land estate and Aboriginal polity provide the locally specific framework for rich stories of shared community life to flourish – this is the work of history that many have found lacking.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Heidi Norman, Therese Apolonio, & Maeve Parker, “Mapping local and regional governance,” Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal (2021), 13(1), 2-14, https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v13.i1.7644.

- Henry Reynolds, “Truth-Telling: History, sovereignty and the Uluru Statement,” Randford: New South Publishing 2020.

Web Resources

- Amy Thomas, Andrew Jakubowicz, Anne Maree Payne, & Heidi Norman, “The Black Lives Matter movement has provoked a cultural reckoning about how Black stories are told,” The Conversation (November 11, 2020): https://theconversation.com/the-black-lives-matter-movement-has-provoked-a-cultural-reckoning-about-how-black-stories-are-told-149544 (last accessed 21 September 2021).

- Robert Parkes, “Black or White? Reconciliation on Australia’s Colonial Past,” Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 16, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-6055.

- AIATSIS, “Land rights”: https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/land-rights (last accessed 21 September 2021).

_____________________

[1] Goodall, H. 1996, Invasion to Embassy: Land in Aboriginal Politics in New South Wales, 1770-1972, Allen and Unwin, Sydney.

[2] Norman, H., 2015, What Do We Want? A political History of Aboriginal land rights in NSW, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra.

[3] [3] See Gillian Cowlishaw’s comments on the limitations of this conception of ‘the old people’ by anthropologist Peter Sutton in his critique of the popular work ‘Dark Emu’, ‘Misreading Dark Emu’ (August 21 2021) available at https://johnmenadue.com/misreading-dark-emu/. And by the author at How the Dark Emu debate limits representation of Aboriginal people in Australia, at https://theconversation.com/how-the-dark-emu-debate-limits-representation-of-aboriginal-people-in-australia-163006..

[4] I refer here to WEH Stanner’s Boyer Lectures, After the Dreaming. See Ann Curthoys (2008) ‘WEH Stanner and the historians’, in Beckett and Hinkson, An Appreciation of Difference: WEH Stanner and Aboriginal Australia, pp 233-238, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra.

[5] As Adam Shoemaker contends in his Black Words, White Page: Aboriginal Literature, 1929-1988 New edition. Canberra, ACT: ANU E Press, 2004.

[6] For the full text and events that culminated in the Uluru Statement from the Heart, see https://fromtheheart.com.au/explore-the-uluru-statement

[7] Pearson, N., 2014, ‘A Rightful place in the nation: Race, recognition and a more complete commonwealth, Quarterly Essay 55.

[8] Elliott., J., and J. H. Muirhead, J. H. 1991, National Report Canberra: Australian Govt. Pub. Service. Wilson, R., 1997, Bringing Them Home : a Guide to the Findings and Recommendations of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families. Sydney: Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission.

[9] Patrick Wolfe (2006) Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native, Journal of Genocide Research, 8:4, pp 387-409.

_____________________

Image Credits

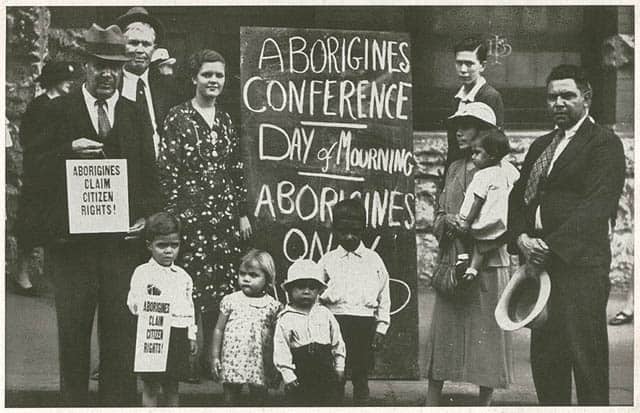

Aborigines day of mourning, Sydney, 26 January 1938 © Public Domain via State Library of New South Wales.

Recommended Citation

Norman, Heidi: Aboriginal Land: A Framework for Narrating the Past. In: Public History Weekly 9 (2021) 7, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-18712.

Editorial Responsibility

Copyright © 2021 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 9 (2021) 7

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-18712

Tags: Australia (Australien), Indigenous Peoples (Indigene Völker)

To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

OPEN PEER REVIEW

Their History

In this article the author shows how central history—an Aboriginal way of knowing and being—is to their sense of the past and the present. Here, restitution does not just mean returning land to traditional owners to manage through locally run land councils. It means restitution of the story for present and future generations. As the author points out, at least since the 1970s, there has been a broad public understanding of the importance of land to Aboriginal cultures. In fact, such an appreciation dates back a very long way but the 1970s saw the notion of land rights hit the national consciousness like never before. This was largely because through their incredibly creative and innovative tent embassy, Aboriginal activists pushed the issue under our noses, on our television screens and in our daily papers.

This was a watershed in Aboriginal politics and as the author notes coincided with Heather Goodall’s landmark history on land in Aboriginal politics. It also coincided with something of a history boom, a productive period of recovery of ‘Aboriginal history’ in the Academy as historians worked to address the silence of their disciplines about this part of the Australian story. This history boom was productive outside of the Academy too. It undergirded social and political change in the Aboriginal policy and governance space as well as ongoing social justice claims. What the author doesn’t say here is how that history experienced a significant retraction at the end of the twentieth century and beginning of the twenty-first century when the ‘history wars’ raged.

This hostile exchange both in and outside of the Academy between historians and public intellectuals, politicians and others about interpretations of the Australian frontier experience was deeply divisive. If it checked the momentum of the ‘new history’ it also profoundly impacted Aboriginal communities many of whom articulated feelings of loss, grief and alienation from what was ultimately a discourse from which they were excluded. So it is little wonder that from the late twentieth century Aboriginal people increasingly saw history—their history—as unfinished business. As the author shows, from the decade of reconciliation to the Uluru Statement Aboriginal people have prioritised truth-telling to national recognition.

Yet, despite Aboriginal history having taken on new directions and frameworks in the aftermath of the history wars, there is a lingering concern at how these histories continue to silence Aboriginal voices and ways of knowing and of history making. For me this is becoming increasingly untenable. Aboriginal histories are and always have been all around us. The two case studies highlighted in this article demonstrate the ways in which local Aboriginal people are taking history into their own hands and reframing and reclaiming the story in ways that are meaningful to them. This reminds me of Shino Konishi’s description of Aboriginal historians bypassing colonial expropriation and exploitation, and the narratives they generate, to produce what she calls extra-colonial histories, histories of Aboriginal worlds that have meaning outside of the white settler paradigm.

One of the really productive parts of the article is the intersection between labour history and Aboriginal history. This is not just in terms of the significant work that custodians and elders are doing to reframe their pasts in ways that are meaningful to them but also recovery of the important labour history of Aboriginal workers in rural communities. There is a strong tradition of Aboriginal labour history which is yet to be fully told and celebrated.

The author describes this as a ‘new framework’ for narrating the past. My sense is that it is not so new, as perhaps, a return to the old, a pattern of recording stories of people and place that is and has always been central to Aboriginal ontologies. Non-Aboriginal historians have long had a fascination with the archive, yet the enlightenment tradition bequeathed an intellectual separation between history and nature, between texts and landscapes. Perhaps it is this legacy that Aboriginal historians are now consciously rejecting. Here land is central to the history produced not as some abstract backdrop to the human drama but as a critical base of recovery and story that is localised and specific to place. This is about respect for the land and the history it holds. It is regenerative and healing and it is their history.