Abstract: The article presents a recent project developed by students of public history from the University of Wroclaw: In February 2020, in an outdoor exhibition on Wroclaw’s Market Square, seventeen biographies of distinguished female residents of Wroclaw after 1945 were presented to the public. The author of the article, the initiator and coordinator of the university’s public history MA program, carried out an evaluation survey among the students after the project was finished. She found that the aspect of gender had not been played an important role in the student’s research process and work on the exhibition. Nonetheless, she concludes that the project yearned valuable insights for students, such as the marginalization of women in history and collective memory.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2020-15173.

Languages: Polski, English, Deutsch

Wystawa, która przez cały luty 2020 r. cieszyła oczy przechodniów na wrocławskim Rynku, to dzieło studentów public history na Uniwersytecie Wrocławskim. Jako inicjatorka i opiekunka tych studiów mam zwyczaj pytać studentów o ich wrażenia i sugestie dotyczące zakończonych zajęć. Tym razem zainteresowało mnie szczególnie to, dlaczego wybrali taki właśnie temat, czy stały za tym jakieś preferencje badawcze lub ideowe, oraz w jakim stopniu powiązanie tematyki z historią kobiet wpłynęło na przebieg prac i końcowy efekt; inaczej rzecz ujmując, czy można w tym przypadku mówić o gender public history.

Projekty studentów public history

Praktyczne projekty realizowane przez studentów są integralną częścią wielu programów studiów z obszaru public history. Pozwalają im zaimplementować wiedzę zdobytą podczas innych zajęć i przekonać się na własnej skórze, z jakimi wyzwaniami przychodzi się mierzyć historykom publicznym: jak przekazać treści w atrakcyjny sposób, pozyskać lub wytworzyć niezbędne materiały, sprostać oczekiwaniom zleceniodawców, współpracować w grupie, zmieścić się w założonym czasie, ale także – w budżecie. Wytwory tych działań dają powody do satysfakcji, a nawet dumy – studentów, prowadzących zajęcia, uczelni, społeczności lokalnej. Bywają też często wykorzystywane do promocji tych studiów – lokalnie, lecz także globalnie – np. podczas konferencji z obszaru public history lub w Internecie i mediach społecznościowych.[1]

Studenci public history na Uniwersytecie Wrocławskim co roku w ramach zajęć z przedmiotu “Public relations, przedsiębiorczość i zarządzanie projektem” projektują i nadzorują wykonanie wystawy plenerowej, która przez miesiąc jest eksponowana na wrocławskim Rynku. Uroczyste otwarcie w ostatnich dniach semestru, zwykle z udziałem władz uczelni, z rektorem włącznie, jest zwieńczeniem ich prac.

Wystawa wrocławskich studentów AD 2020

W poprzednich latach stały tam: Skarby Wrocławia – nieme ofiary II wojny światowej – wystawa poświęcona zaginionym dziełom sztuki z Wrocławia;[2] Tu dorastałem! – Dzieciństwo na Dolnym Śląsku w czterech porach roku – ekspozycja o dzieciństwie we Wrocławiu w czasach PRL i Kolory informacji. Plakaty we Wrocławiu 1945-2000.[3] Gdy zaś piszę te słowa, na Rynku wciąż można oglądać plansze, prezentujące Powojenne wrocławianki i ich dzieła.[4]

Kolejne części ekspozycji, z profesjonalnie zredagowanymi krótkimi tekstami biograficznymi w języku polskim i angielskim oraz korespondującymi z nimi fotografiami, przedstawiają sylwetki siedemnastu kobiet, które żyły we Wrocławiu po 1945 r. i odznaczały się wybitną aktywnością w różnych obszarach – działalności społecznej, nauki, sztuki i kultury. Układ jest chronologiczny – przy czym nie według dat urodzenia bohaterek, lecz okresów ich największych dokonań związanych z Wrocławiem. Zaczyna się więc od przedstawicielek nauki, które przybyły do miasta wkrótce po wojnie: Zofia Gostomska-Zarzycka, jedyna kobieta w grupie, która przybyła w 1945 roku, by organizować we Wrocławiu polskie życie intelektualne, czy Hanna Hirszfeld – pediatra, a także historyczka Ewa Maleczyńska. Kończy się zaś na przyznanej w 2019 r. Nagrodzie Nobla dla mieszkającej we Wrocławiu Olgi Tokarczuk. Nie zabrakło himalaistki, Wandy Rutkiewicz. Wśród przedstawicielek kultury warto wspomnieć także wrocławską malarkę Mirę Aleksiun, która opowiada, jak podróż do Izraela pod koniec lat osiemdziesiątych zapoczątkowała jej powrót do żydowskich korzeni, także w twórczości artystycznej. Jest też obecna zapomniana niemal, ale ostatnio na nowo odkrywana poetka, Marianna Bocian, której książki – jak mówili studenci – są eksponowane w lokalnej bibliotece w dzielnicy, w której mieszkała, ale chyba tylko tam. M. Bocian była też silnie związana z duszpasterstwem akademickim oraz z opozycją demokratyczną w czasach PRL, reprezentowaną na wystawie także przez feministkę, romanistkę, posłankę na Sejm w pierwszych częściowo wolnych wyborach z 1989 r. – Barbarę Labudę oraz przez Hannę Łukowską-Karniej – bliską współpracownicę Kornela Morawieckiego (ojca obecnego premiera Polski) w czasach nielegalnej, radykalnie antykomunistycznej “Solidarności Walczącej” z lat osiemdziesiątych XX wieku.[5]

Studenci o zajęciach

Po zakończonym semestrze przeprowadzam zwykle wśród studentów I roku public history ankietę ewaluacyjną, nieco szerszą niż ta przewidziana przez władze uczelni dla ogółu studentów. Oficjalna jest wypełniana on-line i służy głównie ocenie prowadzących zajęcia, natomiast moja ma tradycyjną papierową formę i skupia się na samych zajęciach. Studenci mają napisać, co im się podobało, co im się nie podobało i jakie mają pomysły na ulepszenie swojego programu studiów. Naturalnie, nie da się całkowicie uniknąć uwag typu: pani X jest bardzo sympatyczna, a pan Y czyta z ekranu. Jednakże uwagi: przydałoby się uwzględnienie umiejętności przewodnickich albo treści przedmiotu X powtarzają to, co już było na przedmiocie Y zostały uwzględnione przy zeszłorocznej modyfikacji programu studiów.

Zajęcia z public relations od zawsze wzbudzają entuzjazm studentów z racji swojej praktycznej formy. Studenci doceniają to, że robią coś “prawdziwego”, że dysponują budżetem, że prowadzący dzieli się nie tylko wiedzą teoretyczną, ale też dużym doświadczeniem praktycznym. Chcieliby takich więcej w kolejnych semestrach.

Należy wspomnieć, że zajęcia te i wystawa są realizowane w ramach współpracy Instytutu Historycznego UWr z Centrum Historii Zajezdnia – wrocławskim muzeum, poświęconym powojennej historii miasta, i centrum badawczym, zajmującym się historią lokalną oraz oral history. Od bieżącego roku akademickiego współpraca ta przybrała sformalizowany charakter w postaci oficjalnej umowy między UWr i Zajezdnią, a wcześniej opierała się na dobrej woli i kontaktach osób zaangażowanych. To Zajezdnia zapewnia prowadzącego z praktycznym doświadczeniem, udostępnia system wystawienniczy oraz pieniądze na pokrycie wszystkich kosztów.

Również w tym roku oceny zajęć z PR były bardzo pozytywne. Na potrzeby tego tekstu przeprowadziłam wśród studentów jeszcze jedną, jeszcze bardziej szczegółową ankietę, dotyczącą tego konkretnego projektu wystawienniczego. Objęła ona 14 osób, które uczestniczyły w pracach. Dodatkowo, przeprowadziłam rozmowę z trojgiem studentów – uczestnikami mojego seminarium magisterskiego z public history, oraz z drem Wojciechem Kucharskim, który zajęcia zaprojektował i prowadził.

Interesowało mnie zwłaszcza, jaki wpływ na pracę nad wystawą i jej efekt miał fakt, że jej tematem przewodnim były dokonania kobiet. Okazało się, że właściwie niewielki. Ani w fazie wyboru tematu, ani w fazie realizacji, studenci nie kierowali się jakimiś głębszymi przesłankami teoretycznymi czy ideowymi. Wybór tematu wystawy odbył się w drodze burzy mózgów, spośród propozycji zgłaszanych przez studentów. Padło ich łącznie kilkadziesiąt. Największym rywalem kobiet był wrocławski film (należy wspomnieć, że we Wrocławiu w latach 1954-2011 funkcjonowała Wytwórnia Filmów Fabularnych, zaangażowana w produkcję bardzo wielu pozycji z klasyki polskiego powojennego kina). Studentów odstraszyła jednak rozległość tematyki filmowej oraz obawa o prawa autorskie do ewentualnego materiału ilustracyjnego.

Następnie każdy z uczestników zajęć skoncentrował się na jednej postaci. Niektórzy zajmowali się bohaterkami, o których już sporo wiedzieli, a inni zaczynali swoją przygodę od samego początku. Ci, których bohaterki wciąż żyją, skupiali się na bezpośrednich kontaktach – przeprowadzali wywiady, zapoznawali się z rodzinnymi pamiątkami. Inni prowadzili poszukiwania archiwalne, lecz także starali się dotrzeć do członków rodzin czy dawnych współpracowników swoich postaci. W odpowiedzi na pytanie, co było dla nich największym zaskoczeniem podczas pracy nad wystawą, niektórzy odnotowali kompletne zapomnienie postaci w instytucjach, z którymi były związane. Motyw zapomnienia, braku wiedzy, nieobecności kobiet w zbiorowej pamięci wrocławian pojawił się też w rozmowie na seminarium i podczas oficjalnego otwarcia wystawy. Studenci mówili, że przy przydzielaniu postaci trudno im było przywołać konkretne nazwiska, choć nie mieliby żadnego kłopotu ze sporządzeniem listy zasłużonych wrocławian-mężczyzn. Dr Kucharski zwracał uwagę na to, że w przypadku wielu bohaterek bardziej znani są ich mężowie niż one same (prof. Ludwik Hirszfeld, mikrobiolog, współodkrywca grup krwi; prof. Jaromir Aleksiun – malarz i grafik; prof. Włodzimierz Trzebiatowski – chemik). Mężowie ci pojawiają się zresztą na prezentowanych na wystawie fotografiach.

Czym jest gender public history?

Studenci zapewniali, że w swojej pracy nie koncentrowali się na płci bohaterek. Traktowali je jako postaci historyczne i uważają, że w taki sam sposób pracowaliby z mężczyznami. Równocześnie nie uszło ich uwadze duże zaufanie, życzliwość, a nawet przyjaźń którą obdarzyły młodych badaczy żyjące bohaterki wystawy. Nie mieli problemu z nieodpłatnym wykorzystaniem fotografii, a Mira Aleksiun osobiście przyszła na wernisaż.

Wszyscy ankietowani napisali, że gdyby mogli wybierać jeszcze raz, ponownie zdecydowaliby się na ten sam temat projektu.

Przykład wrocławskiej wystawy pokazuje, że gender history może być atrakcyjnym tematem dla studentów, nawet jeśli nie wiążą go z konkretnym nurtem w historiografii, nie przywiązują wagi do wartości feministycznych, nie czynią z nich motywu przewodniego swojej pracy. Równocześnie widać, że realizacja projektu pozwoliła studentom osobiście zetknąć ze zjawiskiem marginalizacji roli kobiet w pamięci zbiorowej i w narracjach historycznych, a także ze specyfiką pracy z kobietami jako świadkami i uczestniczkami historii. Należy mieć nadzieję, że wątki kobiece pozostaną obecne również w przyszłych projektach – realizowanych w ramach wrocławskich studiów public history albo przy innych okazjach przez tę grupę studentów. Warto będzie śledzić dalsze owoce tego projektu.

_____________________

Literatura

- Bajer, Magdalena. “Maleczyńscy.” Forum Akademickie, no. 7-8 (2017). https://prenumeruj.forumakademickie.pl/fa/2017/07-08/maleczynscy/ (ostatni dostęp 10.3.2020).

- Bednarek, Stefan, and Jan Tomkowski, eds. Wspomnienia o Mariannie Bocian. Wrocław: Atut, 2019.

- Braun, Monika. Mona: Opowieść o życiu malarki. Wrocław: Via Nova, 2016.

Strony internetowe

- Informacja o projekcie Skarby Wrocławia – nieme ofiary II wojny światowej: https://uni.wroc.pl/skarby-wroclawia-nieme-ofiary-ii-wojny-swiatowej/ (ostatni dostęp 10.3.2020).

- Informacja o projekcie Kolory informacji. Plakaty we Wrocławiu 1945-2000: https://www.f7wroclaw.pl/wroclaw-na-plakacie-i-w-rodzinnym-albumie-wystawa-plenerowa-na-rynku/ (ostatni dostęp 10.3.2020).

- Informacja o projekcie Powojenne wrocławianki i ich dzieła: https://www.zajezdnia.org/wystawa-plenerowa-powojenne-wroclawianki-i-ich-dziela-1 (ostatni dostęp 10.3.2020).

_____________________

[1] Dość wspomnieć film Theo’s Choice (Le Choix de Theo), opracowaną przez studentów Thomasa Cauvina z Uniwersytetu Luizjana czy rozwijany od kilku lat projekt oklejania sygnalizatorów na przejściach dla pieszych w Ottawie informacjami o miejscowych wydarzeniach historycznych (Capital History Kiosks) – dzieło studentów public history z tamtejszego Carleton University pod kierunkiem Davida Deana. Więcej informacji można znaleźć tutaj: https://history.colostate.edu/2018/09/dr-thomas-cauvin-directs-theos-choice-le-choix-de-theo-a-documentary-on-french-education-in-louisiana/ and https://capitalhistory.ca/our-story/ (ostatni dostęp 10.3.2020).

[2] Więcej informacji można znaleźć tutaj https://uni.wroc.pl/skarby-wroclawia-nieme-ofiary-ii-wojny-swiatowej/ (ostatni dostęp 10.3.2020).

[3] Więcej informacji można znaleźć tutaj https://www.f7wroclaw.pl/wroclaw-na-plakacie-i-w-rodzinnym-albumie-wystawa-plenerowa-na-rynku/ (ostatni dostęp 10.3.2020).

[4] Więcej informacji można znaleźć tutaj https://www.wroclaw.pl/go/wydarzenia/sztuka/1298760-wernisaz-wystawy-powojenne-wroclawianki-i-ich-dziela (ostatni dostęp 10.3.2020).

[5] Pełen wykaz postaci znajduje się m.in. https://www.radioram.pl/articles/view/38192/Powojenne-wroclawianki-i-ich-dziela-do-obejrzenia-na-Rynku-PODCAST# (ostatni dostęp 10.3.2020).

_____________________

Licencjonowanie obrazu

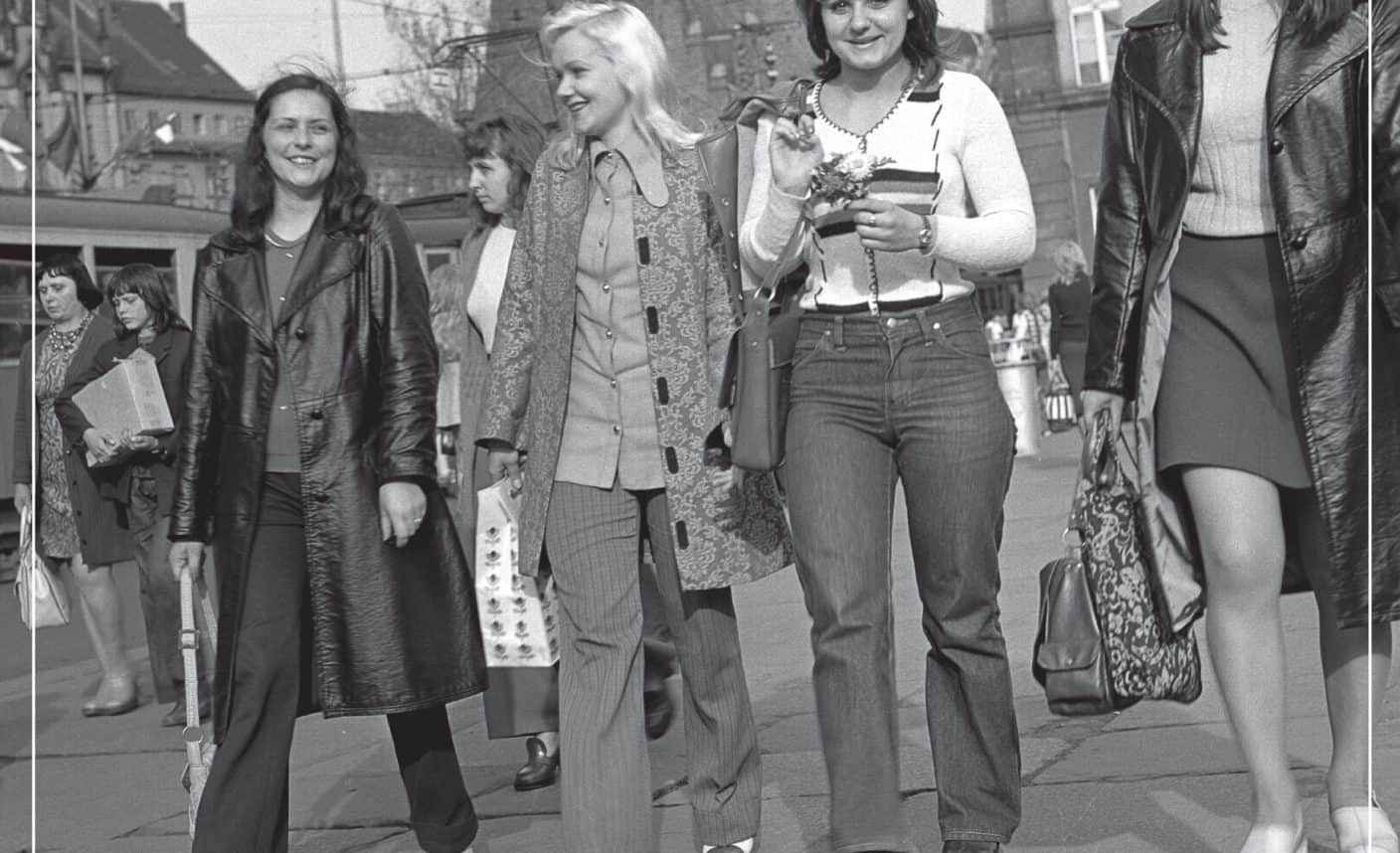

Official poster for the exhibition Women of Post-War Wroclaw. © 2020 Zajezdnia History Center.

Zalecane cytowanie

Wojdon, Joanna: Women of Post-War Wroclaw – Is This Gender Public History? In: Public History Weekly 8 (2020) 3, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2020-15173.

Odpowiedzialność redakcyjna

Isabella Schild / Thomas Hellmuth (Team Vienna)

The exhibition which passers-by on the Market Square in Wroclaw could enjoy all February 2020 was the work of students of public history. As an initiator and coordinator of this MA program, I usually ask students for evaluation of the courses they have just finished, for their impressions and suggestions. This time I was particularly interested in the reasons why they had chosen this particular topic, if they had any particular research or ideological preferences, and to what extent the fact of dealing with gender history impacted the course of the project work and its final result. Or, to put it otherwise: can we call this project an example of gender public history?

The Projects

Practical projects implemented by students are an integral part of many study programs in the field of public history. Students are able to implement the knowledge acquired during other classes and see for themselves the challenges that public historians have to face: How to convey content in an attractive way, acquire or produce the necessary materials, meet the expectations of patrons, cooperate in a group, make the time, and yet also stay within budget. The results of these activities give reasons for satisfaction and even pride amongst the students themselves, their lecturers, universities, and the local community. The projects are also often used to promote these study programs—not only locally, but also globally e.g. during public history conferences or on the internet and social media.[1]

Every year, students of public history at the University of Wrocław—as part of the course “Public Relations, Entrepreneurship and Project Management”—both design and supervise the implementation of an outdoor exhibition which is later displayed for one month on Wrocław Market Square. The opening ceremony held during the last days of the semester, usually with the participation of key university figures including the rector, represents the culmination of their work.

The Exhibition

Projects in recent years have included Treasures of Wrocław: The Silent Victims of World War II, an exhibition dedicated to lost works of art from Wrocław;[2] I Grew Up Here! Childhood in Lower Silesia in Four Seasons, an exhibition about childhood in Wrocław under communism; and Colors of Information: Posters in Wrocław 1945–2000.[3] At the time of writing, one can still visit the Market Square to examine the presentation of post-war female residents of Wrocław and their works.[4]

The display boards of the exhibition, with professionally edited, short biographical texts in Polish and English and corresponding photographs, present the portraits of 17 women who lived in Wrocław after 1945 and were distinguished by outstanding achievements in various areas—social activities, science, art, and culture. The layout is chronological—not according to the dates of birth of the heroines, but to the periods of their greatest achievements related to Wrocław. It therefore begins with the representatives from science who came to the city shortly after the war: Zofia Gostomska-Zarzycka, the only woman in the group of people who came in 1945 to organize Polish intellectual life in Wrocław; Hanna Hirszfeld, a pediatrician; and historian Ewa Maleczyńska. It ends with the 2019 Nobel Prize laureate Olga Tokarczuk, who lives in Wrocław. Wanda Rutkiewicz, the first European woman to reach the summit of Mount Everest, is also represented. Among the cultural representatives, the Wrocław painter Mira Aleksiun explains how a trip to Israel in the late 1980s sparked her return to her Jewish roots, also in terms of her artistic output. There is also the almost forgotten, but recently rediscovered poet Marianna Bocian, whose books are exhibited in probably only one sole place, namely the local library in the district where she lived. Bocian was also strongly associated with academic pastoral care and the democratic opposition during the Polish People’s Republic (PRL), which is also represented at the exhibition by the feminist, Romanist, and deputy in the Sejm (lower house of the Polish parliament) following the first partly free elections in 1989 Barbara Labuda, and Hanna Łukowska-Karnia, a close collaborator of Kornel Morawiecki (the father of the current Polish prime minister) in the illegal, radically anti-communist “Fighting Solidarity” (Solidarność Walcząca) organization of the 1980s.[5]

Popularity

At the end of the semester, I usually carry out an evaluation survey among first-year students of public history, slightly broader than that provided by university administrators for all students. The official one is completed online and is mainly used for assessing the lecturers, while mine has a traditional paper format and focuses on the classes themselves. Students are asked to write what they liked, what they didn’t like, and what ideas they have to improve their study program. Naturally, there are comments such as “Ms. X is very nice” and “Mr. Y reads from the screen.” However, the comments related to the content and structure of the study program can prove to be very helpful. For example, “it would be useful to include leadership skills in the program” and “the content of class X repeats what was already taught in class Y” were taken into account during last year’s modification of the study program.

Public relations classes have always aroused the enthusiasm of students because of their practical format. Students appreciate that they are doing something “real”, that they have a budget, and that the teacher shares not only theoretical knowledge but also extensive practical experience. They have expressed that they would like to have more such classes in the following semesters.

It should be mentioned that these classes as well as the aforementioned exhibitions are carried out as part of the cooperation between the Department of History at the University of Wrocław and the Zajezdnia History Center, a Wrocławian museum dedicated to the post-war history of the city and a research center that deals with local history and oral history. Since the current academic year, this cooperation has become formalized in the official agreement between the University of Wrocław and Zajezdnia—previously, it was based on the goodwill and contacts of those involved. Zajezdnia provides the lecturers with practical experience, the exhibition system, and funds to cover all costs.

Not surprisingly, the evaluations of the public relations classes were very positive for this year also. For the purposes of this text, I conducted one more detailed survey of this particular exhibition project among the students. It covered 14 people who participated in the work. In addition to this, I interviewed three students—participants of my MA seminar in public history—and Dr. Wojciech Kucharski, who designed and conducted the classes.

Women’s Achievements

I was particularly interested in the impact of the topic of women’s achievements on the implementation process of the work on the exhibition and its results. It turned out to be small. My findings were that the students, neither at the stage of topic selection nor during the implementation phase, were guided by some deeper theoretical or ideological premises regarding gender. The topic of the exhibition was chosen by brainstorming from among the proposals submitted by students. Several dozens of them were showcased. The biggest rival of the women-oriented topic was Wrocław’s role in film history (between 1954 and 2011, a feature film production company (Wytwórnia Filmów Fabularnych) operated in Wrocław and was involved in the production of many classics of Polish post-war cinema). Students, however, were deterred by the breadth of the film topic and the potential copyright issues with any illustrative material.

During the preparation process, each of the students focused on one personality. Some dealt with persons whom they already knew a lot about, while others started from scratch. Those whose subjects of interest are still alive, focused on direct contacts—interviews, meetings to familiarize themselves with their families, memories, etc. Others conducted archival research, but also tried to reach family members or former collaborators of their respective subjects. In response to the question “What was your biggest surprise while working on the exhibition?”, some noted complete obliviousness of the personalities in the institutions with which they were associated. The motive of forgetfulness, lack of knowledge, and the absence of women in the collective memory of Wrocławian residents were also discussed in the seminar and during the official opening of the exhibition. Students said that it was difficult for them to recall specific names while assigning historical figures, although they would have no trouble compiling a list of distinguished male personalities connected with the city. Dr. Kucharski pointed out that in many cases, the husbands of the women presented in the exhibitions are better known to the public e.g. Prof. Ludwik Hirszfeld, a microbiologist and co-discoverer of blood groups; Prof. Jaromir Aleksiun, a painter and graphic artist; and Prof. Włodzimierz Trzebiatowski, a chemist. These men also appear in the photographs presented at the exhibition.

Gender Public History

Students commented that they did not focus on the gender issues in their work. They treated their personalities as historical figures and believed that they would work with men in the same way. At the same time, they cherished the great trust, kindness, and even friendship that they experienced during their work. They had no problem with the free use of photography, and Mira Aleksiun personally came to the opening. All respondents wrote that if they could choose again, they would once more decide on the same topic for the project.

The example of the Wrocław exhibition shows that gender history can be an attractive topic for students, even if they do not connect it with a particular historiographical trend, attach importance to feminist values, or make them the leitmotif of their work. At the same time, it can be seen that the implementation of the project allowed students to personally encounter the phenomenon of the marginalization regarding the role of women in collective memory and in historical narratives, as well as the specificity of working with women as witnesses and participants of history. It is to be hoped that women’s themes will also remain present in future projects—implemented as part of public history studies in Wrocław or on other occasions by this group of students. It will be worth observing what further fruits this project will bear.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Bajer, Magdalena. “Maleczyńscy.” Forum Akademickie, no. 7-8 (2017). https://prenumeruj.forumakademickie.pl/fa/2017/07-08/maleczynscy/ (last accessed 10 March 2020).

- Bednarek, Stefan, and Jan Tomkowski, eds. Wspomnienia o Mariannie Bocian. Wrocław: Atut, 2019.

- Braun, Monika. Mona: Opowieść o życiu malarki. Wrocław: Via Nova, 2016.

Web Resources

- Information on the project Treasures of Wrocław: The Silent Victims of World War II: https://uni.wroc.pl/skarby-wroclawia-nieme-ofiary-ii-wojny-swiatowej/ (last accessed 10 March 2020).

- Information on the project Colors of Information: Posters in Wrocław 1945–2000: https://www.f7wroclaw.pl/wroclaw-na-plakacie-i-w-rodzinnym-albumie-wystawa-plenerowa-na-rynku/ (last accessed 10 March 2020).

- Information on the project Post-war Female Wrocławians and their Works on the website of Zajezdnia History Center: https://www.zajezdnia.org/wystawa-plenerowa-powojenne-wroclawianki-i-ich-dziela-1 (last accessed 10 March 2020).

_____________________

[1] Examples for such projects are Theo’s Choice (Le Choix de Theo), developed by students of Thomas Cauvin from the University of Louisiana, and Capital History Kiosks, a project where information about local historical events are wrapped around traffic lights at pedestrian crossings in Ottawa—this work has been developed annually by public history students from local Carleton University under the direction of David Dean. For further information, see https://history.colostate.edu/2018/09/dr-thomas-cauvin-directs-theos-choice-le-choix-de-theo-a-documentary-on-french-education-in-louisiana/ and https://capitalhistory.ca/our-story/ (last accessed 10 March 2020).

[2] For further information, see https://uni.wroc.pl/skarby-wroclawia-nieme-ofiary-ii-wojny-swiatowej/ (last accessed 10 March 2020).

[3] For further information, see https://www.f7wroclaw.pl/wroclaw-na-plakacie-i-w-rodzinnym-albumie-wystawa-plenerowa-na-rynku/ (last accessed 10 March 2020).

[4] See the project website https://www.wroclaw.pl/go/wydarzenia/sztuka/1298760-wernisaz-wystawy-powojenne-wroclawianki-i-ich-dziela (last accessed 10 March 2020).

[5] A complete list of the personalities on display can be found on https://www.radioram.pl/articles/view/38192/Powojenne-wroclawianki-i-ich-dziela-do-obejrzenia-na-Rynku-PODCAST# (last accessed 10 March 2020).

_____________________

Image Credits

Official poster for the exhibition Women of Post-War Wroclaw. © 2020 Zajezdnia History Center.

Recommended Citation

Wojdon, Joanna: Women of Post-War Wroclaw – Is This Gender Public History? In: Public History Weekly 8 (2020) 3, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2020-15173.

Editorial Responsibility

Isabella Schild / Thomas Hellmuth (Team Vienna)

Den ganzen Februar 2020 konnten Passant*innen am Breslauer Marktplatz eine Ausstellung bewundern, die von Studierenden der Public History konzipiert worden war. Als Initiatorin und Koordinatorin dieses Masterstudienganges befrage ich üblicherweise die Studierenden zu den Kursen, die sie gerade absolviert haben, zu ihren Eindrücken und Anregungen. Dieses Mal interessierte ich mich vor allem dafür, warum sie sich für dieses konkrete Projektthema entschieden hatten, ob sie bestimmte forschungstechnische oder ideologische Präferenzen hatten und in welchem Ausmaß die Auseinandersetzung mit Geschlechtergeschichte sich auf den Verlauf der Projektarbeit und das Endergebnis auswirkte. Oder, um es anders zu formulieren: Handelt es sich bei diesem Projekt um ein Beispiel für Gender Public History?

Die Projekte

Praxisnahe, von Studierenden umgesetzte Projekte sind ein integraler Teil vieler Studienprogramme im Bereich der Public History. Die Studierenden können so ihr Wissen, das sie sich in anderen Fächern angeeignet haben, anwenden und selbst erfahren, vor welchen Herausforderungen Historiker*innen stehen: Wie kann man Inhalte attraktiv vermitteln, das nötige Material zur Verfügung stellen und/oder produzieren, den Erwartungen der Förder*innen entsprechen, als Gruppe zusammenarbeiten, die Zeit einteilen und dennoch das Budget nicht überschreiten? Die Ergebnisse dieser Aktivitäten können Anlass zur Zufriedenheit geben und zum Stolz der Studierenden, ihrer Dozent*innen, der Universitäten und der örtlichen Gemeinschaft beitragen. Die Projekte werden auch oft genutzt, um die Studienprogramme nicht nur national, sondern auch international, wie zum Beispiel während Public-History-Konferenzen oder im Internet oder auf den Sozialen Medien, zu promoten.[1]

Im Rahmen des Kurses “Öffentlichkeitsarbeit, Unternehmerschaft und Projektmanagement” entwickeln und betreuen Public-History-Studierende der Universität Breslau jedes Jahr die Umsetzung einer im Außenraum stattfindenden Ausstellung, die später für einen Monat am Marktplatz in Breslau zu sehen ist. Die Eröffnung, die in den letzten Tagen des Semesters und im Beisein von offiziellen Vertreter*innen der Universität wie auch dem Rektor stattfindet, stellt den Höhepunkt ihrer Arbeit dar.

Die Ausstellung

Projekte der letzten Jahre inkludierten die Ausstellungen Schätze von Breslau: Die stummen Opfer des Zweiten Weltkriegs über die verlorenen Kunstwerke von Breslau, Ich wuchs hier auf! Kindheit in Niederschlesien durch die vier Jahreszeiten über die Kindheit im kommunistischen Breslau und Farben der Information: Plakate in Breslau 1945–2000.[3] Zum Zeitpunkt der Entstehung dieses Texts kann man am Marktplatz noch die Präsentation zu den Bewohnerinnen und ihrer Arbeit im Breslau der Nachkriegszeit besuchen.[4]

Die Schautafeln der Ausstellung, mit professionell verarbeiteten Kurzbiografien auf Polnisch und Englisch und dazugehörigen Fotografien, präsentieren 17 Porträts von Frauen, die in Breslau nach 1945 lebten und die sich durch ihre außergewöhnlichen Verdienste in verschiedenen Bereichen auszeichneten – sei es in sozialen, wissenschaftlichen, künstlerischen oder kulturellen. Die Präsentation ist chronologisch aufgebaut, orientiert sich aber nicht nach den Geburtsdaten der Heroinen, sondern nach ihren größten Errungenschaften in Verbindung mit Breslau. Sie beginnt daher mit Stellvertreterinnen aus der Wissenschaft, die kurz nach dem Krieg in die Stadt kamen: Zofia Gostomska-Zarzycka, die einzige Frau einer bedeutenden Gruppe, die nach 1945 nach Breslau kam, um ein Leben für intellektuelle Pol*innen zu organisieren, ferner die Kinderärztin Hanna Hirszfel und die Historikerin Ewa Maleczyńska. Sie endet mit Olga Tokarczuk, der Nobelpreisträgerin von 2019, die auch in Breslau lebt. Ebenso ist Wanda Rutkiewicz, die erste Europäerin, die den Mount Everest bestiegen hat, vertreten. Unter den kulturellen Stellvertreterinnen erklärt die Breslauer Malerin Mira Aleksiun, wie eine Reise nach Israel in den späten 1980er-Jahren die Rückkehr zu ihren jüdischen Wurzeln auslöste und diese wiederum ihr künstlerisches Schaffen beeinflusste. Auch die fast vergessene, aber kürzlich wiederentdeckte Dichterin Marianna Bocian, deren Bücher (vermutlich) nur in der örtlichen Bibliothek des Bezirks, in dem sie auch lebt, ausgestellt werden, ist Teil davon. Bocian wird auch stark mit der akademischen Seelsorge und der demokratischen Opposition während der Volksrepublik Polen (PRL) assoziiert. Die Opposition ist in der Ausstellung ebenfalls vertreten durch Barbara Labuda, die Feministin, Romanistin und Abgeordnete der Sejm (Unterhaus des polnischen Parlaments) nach den ersten teilweise freien Wahlen 1989 war, und durch Hanna Łukowska-Karnia, einer engen Mitarbeiterin von Kornel Morawiecki (Vater des aktuellen polnischen Ministerpräsident) in der illegalen, radikal anti-kommunistischen Organisation “Kämpfende Solidarität” der 1980er-Jahre.[5]

Beliebtheit

Am Ende des Semesters führe ich bei den erstsemestrigen Public-History-Studierenden für gewöhnlich eine Evaluierung durch, die etwas breiter als jene von der Universität für alle Studierenden angelegt ist. Die offizielle Evaluation erfolgt nur online und wird hauptsächlich für die Beurteilung der Lehrenden verwendet, während meine das traditionelle Papierformat aufweist und sich auf den Unterricht konzentriert. Die Studierenden werden angeregt niederzuschreiben, was ihnen gefallen hat und was nicht und welche Ideen sie für die Verbesserung des Studienprogramm anbringen möchten. Natürlich gibt es Antworten wie “Frau X ist sehr nett” und “Herr Y liest vom Bildschirm ab”. Doch die auf den Inhalt und die Struktur des Studienprogramms bezogenen Kommentare können jedenfalls sehr hilfreich sein. Zum Beispiel konnten Aussagen wie “es wäre nützlich, wenn Führungsfähigkeiten in das Programm mit aufgenommen werden” oder “der Inhalt von Kurs X wiederholt das, was in Kurs Y bereits gelehrt wurde” letztes Jahr in der Modifikation des Studienprogramms berücksichtigt werden.

Aufgrund des praxisnahen Formates haben Kurse zur Öffentlichkeitsarbeit immer schon das Interesse der Studierenden geweckt. Sie schätzen es, dass sie etwas “Reales” tun und mit einem Budget arbeiten können und dass die Lehrenden nicht nur theoretisches Wissen, sondern auch umfangreiche praktische Erfahrungen teilen. Sie möchten in den folgenden Semestern gerne mehr Kurse dieser Art besuchen.

Es sollte betont werden, dass diese Kurse und die zuvor erwähnten Ausstellungen als Teil einer Kooperation zwischen dem Historischen Institut der Universität Breslau und dem Geschichtlichen Zentrum Zajezdnia, einem Breslauer Museum zur Nachkriegsgeschichte der Stadt und Forschungszentrum zur lokalen Geschichte und Oral History, durchgeführt wurden. Seit diesem Studienjahr wurde die Zusammenarbeit in einem Vertrag zwischen der Universität Breslau und Zajezdnia offiziell gemacht – zuvor war sie von den der Kulanz und den involvierten Kontakten anhängig. Zajezdnia stellt den Lehrenden die praktische Erfahrung zur Verfügung, das Ausstellungssystem und die Mittel, um alle Kosten zu decken.

Es ist nicht überraschend, dass die Evaluierung der Kurse zur Öffentlichkeitarbeit auch dieses Jahr sehr positiv war. Für diesen Text habe ich eine weitere detailliertere Studierendenumfrage zu diesem bestimmten Ausstellungsprojekt gemacht. Daran nahmen 14 Studierende teil. Zusätzlich habe ich drei Studierende – Teilnehmer*innen meines Masterseminars zu Public History – und Dr. Wojciech Kucharski, der die Kurse gestaltet und geleitet hat, befragt.

Errungenschaften von Frauen

Im Speziellen war ich an der Auswirkung des Themas zu den Errungenschaften der Frauen auf den Umsetzungsprozess der Arbeit und die Resultate interessiert. Diese war jedoch sehr klein. Daraus lernte ich, dass die Studierenden weder bei der Themenfindung noch während der Implementierungsphase in Hinblick auf tiefergehende theoretische oder ideologische Voraussetzungen in Bezug auf die Genderthematik angeleitet wurden. Das Ausstellungsthema wurde durch Brainstorming aus all den eingereichten Vorschlägen der Studierenden ausgewählt. Einige Duzend davon wurden ebenfalls ausgestellt. Der beliebteste Gegenvorschlag zum Frauenthema war die Rolle Breslaus in der Filmgeschichte (zwischen 1954 und 2011 gab es eine Filmproduktionsgesellschaft in Breslau, die an der Produktion vieler Klassiker des polnischen Nachkriegskinos beteiligt war). Die Studierenden waren jedoch vom Umfang des Filmthemas und den potenziellen Urheberrechtsfragen des Bildmaterials abgeschreckt.

Während des Vorbereitungsprozesses beschäftigten sich alle Studierenden mit jeweils einer Persönlichkeit. Manche befassten sich mit Personen, von denen sie bereits viel wussten, während andere von vorne beginnen mussten. Wenn die Persönlichkeit noch lebte, suchten sie den direkten Kontakt und führten Interviews und machten sich mit deren Familien, Erinnerungsstücken etc. vertraut. Andere führen Recherchen in Archiven aus, versuchten aber auch die Familienmitglieder oder ehemaligen Mitarbeiter*innen ausfindig zu machen. Als Antwort auf die Frage “Was war deine größte Überraschung während der Arbeit an der Ausstellung?” merkten manche an, dass sie von den in ihren Fachgebieten bedeutenden Personen nichts wussten. Das Motiv der Vergesslichkeit, die Unwissenheit und die Abwesenheit der Frauen im kollektiven Gedächtnis der Breslauer*innen wurden ebenso in den Seminaren und während der offiziellen Eröffnung der Ausstellung diskutiert. Die Studierenden meinten, dass es für sie schwer war, sich bei der Zuordnung historischer Personen die spezifischen Namen ins Gedächtnis zu rufen, obwohl es ihnen leicht fiel, eine Liste mit herausragenden, mit der Stadt assoziierten männlichen Personen zusammenzutragen. Dr. Kucharski wies in manchen Fällen darauf hin, dass die Ehemänner der Frauen, die in den Ausstellungen präsentiert wurden, der Öffentlichkeit besser bekannt waren, etwa der Mikrobiologe und Mitentdecker der Blutgruppen Prof. Ludwik Hirszfeld, der Maler und Grafikkünstler Prof. Jaromir Aleksiun, und der Chemiker Prof. Włodzimierz Trzebiatowski. Diese Männer tauchten in den Fotografien in der Ausstellung ebenfalls auf.

Was ist Gender Public History?

Die Studierenden kommentierten, dass sie sich in ihrer Arbeit nicht auf den Genderaspekt fokussierten. Sie behandelten die Persönlichkeiten als historische Personen und glaubten, dass sie zu Männern auf die gleiche Weise gearbeitet hätten. Gleichzeitig schätzten sie das Vertrauen, die Herzlichkeit und sogar die Freundschaftlichkeit, die ihnen während der Arbeit entgegengebracht wurden. Für sie war die freie Verwendung von Fotografien kein Problem, und Mira Aleksiun kam persönlich zur Eröffnung. Alle Antwortenden schrieben, dass, wenn sie nochmal wählen könnten, sich wieder für dieses Projektthema entscheiden würden.

Das Beispiel der Breslauer Ausstellung zeigt, dass Geschlechtergeschichte ein attraktives Thema für Studierende sein kann, auch wenn sich diese nicht an einen spezifischen historiografischen Trend anbinden, die Wichtigkeit der feministischen Themen betonen oder diese als Leitmotiv ihrer Arbeit einsetzten. Gleichzeitig wird deutlich, dass die Projektumsetzung es den Studierenden ermöglichte, persönlich das Phänomen der Ausgrenzung in Bezug auf die Rolle der Frauen im kollektiven Gedächtnis und in der historischen Narrativen sowie die Spezifität der Arbeit mit Frauen als Zeitzeuginnen und Teilnehmerinnen der Geschichte zu entdecken. Es bleibt abzuwarten, ob die Frauenthemen Bestandteil künftiger Projekte – umgesetzt als Teil der Public-History-Studien in Breslau oder zu anderen Anlässen dieser studentischen Gruppe – bleiben werden. In der Zukunft wird sich zeigen, welche Früchte dieses Projekt noch tragen wird.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Bajer, Magdalena. “Maleczyńscy.” Forum Akademickie, no. 7-8 (2017). https://prenumeruj.forumakademickie.pl/fa/2017/07-08/maleczynscy/ (letzter Zugriff 10.3.2020).

- Bednarek, Stefan, and Jan Tomkowski, eds. Wspomnienia o Mariannie Bocian. Wrocław: Atut, 2019.

- Braun, Monika. Mona: Opowieść o życiu malarki. Wrocław: Via Nova, 2016.

Webressourcen

- Information zum Projekt Schätze von Breslau: Die stummen Opfer des Zweiten Weltkriegs: https://uni.wroc.pl/skarby-wroclawia-nieme-ofiary-ii-wojny-swiatowej/ (letzter Zugriff 10.3.2020).

- Information zum Projekt Farben der Information: Plakate in Breslau 1945–2000: https://www.f7wroclaw.pl/wroclaw-na-plakacie-i-w-rodzinnym-albumie-wystawa-plenerowa-na-rynku/ (letzter Zugriff 10.3.2020).

- Information zum Projekt Frauen und ihre Arbeit im Breslau der Nachkriegszeit auf der Website des Geschichtlichen Zentrum Zajezdnia: https://www.zajezdnia.org/wystawa-plenerowa-powojenne-wroclawianki-i-ich-dziela-1 (letzter Zugriff 10. März 2020).

_____________________

[1] Beispiele solcher Projekte sind Theo’s Choice (Le Choix de Theo), entwickelt von Studierenden von Thomas Caubin aus der Universität Louisiana, und Capital History Kiosks, ein Projekt bei dem Informationen zu lokalen, historischen Ereignissen um Straßenbeleuchtungen bei Fußgängerübergängen in Ottawa gewickelt wurden – dieses Projekt wurde jährlich bei Public History-Studierenden der Universität Carleton unter der Direktion von David Dean entwickelt. Für mehr Informationen, siehe https://history.colostate.edu/2018/09/dr-thomas-cauvin-directs-theos-choice-le-choix-de-theo-a-documentary-on-french-education-in-louisiana/ and https://capitalhistory.ca/our-story/ (letzter Zugriff 10.3.2020).

[2] Für mehr Informationen, siehe https://uni.wroc.pl/skarby-wroclawia-nieme-ofiary-ii-wojny-swiatowej/ (letzter Zugriff 10.3.2020).

[3] Für mehr Informationen, siehe https://www.f7wroclaw.pl/wroclaw-na-plakacie-i-w-rodzinnym-albumie-wystawa-plenerowa-na-rynku/ (letzter Zugriff 10.3.2020).

[4] Für mehr Informationen, siehe https://www.wroclaw.pl/go/wydarzenia/sztuka/1298760-wernisaz-wystawy-powojenne-wroclawianki-i-ich-dziela (letzter Zugriff 10.3.2020).

[5] Eine vollständige Liste der ausgestellten Personen kann hier eingesehen werden: https://www.radioram.pl/articles/view/38192/Powojenne-wroclawianki-i-ich-dziela-do-obejrzenia-na-Rynku-PODCAST# (letzter Zugriff 10.3.2020).

_____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

Official poster for the exhibition Women of Post-War Wroclaw. © 2020 Zajezdnia History Center.

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Wojdon, Joanna: Women of Post-War Wroclaw – Is This Gender Public History? In: Public History Weekly 8 (2020) 3, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2020-15173.

Redaktionelle Verantwortung

Isabella Schild / Thomas Hellmuth (Team Vienna)

Copyright (c) 2020 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 8 (2020) 3

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2020-15173

Tags: Gender, Language: Polish, Museum, Poland (Polen)