Abstract: This article reflects on the conceptualization of history embedded in museum exhibitions and discusses competing ideas of history conveyed by museums. Based on the author’s visit to the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano (Italy) and the Munich Documentation Centre for the History of National Socialism (Germany), she considers the exhibitions in the larger context of history and interpretations in museums. This piece digs into public history strategies and sheds light on the cracks between the public’s understanding and academic definitions of history.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-14613

Languages: Italian, English, German

Questo blog riflette sull’idea di storia insita in alcune collezioni museali e sulle idee di storia che i musei possono trasmettere. L’autrice mette a confronto il Museo Archeologico dell’Alto-Adige di Bolzano (Italia) e il Centro Documentazione per la Storia del Nazional-socialismo di Monaco (Germania), analizza le differenti strategie in cui questi due spazi rendono pubblica la storia e mostra le discrepanze tra la storia come problema e la storia come descrizione del passato.

Un museo per la mummia piú famosa al mondo

Bolzano, é la provincia italiana situata vicino al confine italo-autriaco, é bilingue e biculturale ed é cosiderata la porta delle Dolomiti. L’attrazione della cittá é senza dubbio Ötzi, conosciuto anche come l’uomo venuto dal ghiaccio, una mummia in perfetto stato di conservazione risalente a 5300 anni fa scoperta il 19 settembre 1991 da due escursionisti tedeschi trovano un corpo nelle Alpi Venoste. Attorno a questa sensazionale scoperta, l’Alto-Adige decise di costruire un apposito museo a Bolzano – il Museo Archeologico dell´Alto-Adige – che dal 1998 conserva il corpo e gli effetti personali che l’uomo portava con sé. Archeologici, antropologi, scienziati naturali e medici hanno contribuito all’allestimento di una mostra multidiscplinare i cui chiari pannelli esplicativi affiancano strategie espositive efficaci.

Nonostante l’entusiasmo della stragrande maggioranza dei visitatori, durante il mio giro del museo continuavo a chiedermi quale fosse il messaggio che potevo trarre da tutte quelle informazioni e quale fosse il messaggio che i curatori volessero trasmettere. Preservare Ötzi per le future generazioni é una prioritá del museo e sicuramente non é impresa da poco.

Un centro di documentazione per la storia del nazional-socialismo

Dal punto di vista storico, Monaco di Baviera é nota per essere stata la capitale del nazional-socialismo e in particolare il quartiere Maxvorstadt mostra ancora l’impronta del regime a livello architettonico. Proprio dove il partito nazista aveva la sua sede, il governo bavarese ha costruito il Centro di Documentazione per la Storia del Nazional Socialismo nel 2015. Lo scopo principale del centro é quello di mostrare lo sviluppo del movimento a partire dai suoi prodromi fino ai giorni nostri e il messaggio che se ne ricava é un monito sulla fragilitá e sulla vulnerabilitá dei nostri regimi democratici.

Quattro piani in cui sono esposti documenti di ogni tipo – video, volantini, libri, fotografie, ecc… – e un´ultima sezione sulla lunga durata del regime nazista, una sezione fondamentale nel connettere passato e presente e nel rendere questo spazio vivo. Ho visitato questo museo tre volte in un anno e ogni volta é stata un´esperienza diversa.

La storia nel mondo

Quando dei curatori musealizzano una storia, essi muovono – anche implicitamente – da una idea specifica di storia, o meglio, da una certa filosofia della storia.

In breve, il primo museo di cui ho parlato é la presentazione di una scoperta sensazionale e gli scienziati hanno dedotto da Ötzi e dai resti dei suoi oggetti personali una incredibile mole di informazioni preziose. Certamente l’idea di storia dietro questa musealizzazione non é quella di histoire événementielle, infatti tutti i ritrovamenti sono funzionali per ricostruire in senso piú ampio possibile il contesto sociale, ambientale, economico di Ötzi. Ma tutte queste informazioni rimangono confinate nel reame del passato. Mentre giravo per le sale mi sembrava che il museo non rispondesse alla domanda “Che cosa questa storia puó dirci oggi?”

Al contrario, i principi che hanno guidato la musealizzazione del CDNS sono la capacitá di istaurare un dialogo tra i visitatori e le storie esposte e il tentativo di far diventare il nazional-sociale un fenomeno di rilievo per il presente e per tutti noi.[1] L’idea dietro tale museo é di “mettere la storia a disposizione e nel mondo”,[2] di aiutare le persone a creare e capire la loro storia,[3] di fornire “passati utilizzabili”.[4] Per dirlo in breve, questo museo si fonda sul significato della storia come public history.

Come storici influenti – quali Edward H. Carr, Fernand Brudel, Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre – hanno affermato, la storia non é né una lista di eventi né la mera descrizione dei fatti. La storia é il fitto intreccio di presente, passato e futuro, di razionalitá e prospettive diverse in cui l’hic et nunc dello storico o della storica é il punto essenziale.[5]

E per me la storia di Ötzi rimane principalmente una storia transnazionale e ambientale. Istituzioni e singoli italiali, tedeschi e austriaci si sono misurati e interessati alla vicenda e le Alpi sono una regione che valica i confini nazionali. La localizzazione della mummia a 90 metri dal confine, sul versante italiano, ha determinato che fosse l’Italia a conservare i ritrovamenti ma, nonostante ció, la scoperta dell’uomo preistorico ha offerto uno spazio per la cooperazione tra i Paesi alpini. Una sezione che illustri il ruolo che la storia, e la cultura in generale, rivestono in questo contesto potrebbe attualizzare il passato in mostra. E lo stesso potrebbe valere per un secondo elemento, ossia la riflessione sui cambiamenti dovuti al surriscaldamento globale. Poiché i ghiacciai alpini si stanno riducendo, corpi mummuficati, rari oggetti di rilievo archeologico e storico, bunker e caverne per secoli sepolti dal giaccio stanno progressivamente riemergendo.

La cooperazione internazionale nell´Europa delle barriere doganali e la conservazione dell’ambiente dolomitico sono al giorno d’oggi sorvegliati speciali, fragili quanto la nostra democrazia.

Perché è importante la storia

Che ruolo ha la storia oggi? Questa dovrebbe essere la domanda centrale che ogni museo che si occupi di storia dovrebbe prendere seriamente in considerazione e a cui provare a rispondere attraverso diverse pratiche comunicative. Partendo dalla consapevolezza che la storia non coicide con il passato, gli eventi e gli sforzi di conservare e divulgare sono necessari ma non sufficienti a elaborare un discorso storico. I musei non sono né biblioteche né archivi, i musei sono spazi che vivono (o muoiono) e, soprattutto negli anni in cui l’uso pubblico della storia sta prendendo sempre piú piede, concepire il museo come luogo di divulgazione non é piú abbastanza.

Per citare il filosofo italiano Benedetto Croce,[6] se la storia é sempre contemporanea, é altrettanto vero che la storia é anche sempre pubblica – nella misura in cui essa si genera dalle trasformazioni che coinvolgono societá e ambiente – e deve essere consapevolmente pubblica. Per esprirmere al meglio la dimensione e la missione pubblica della storia, curatori museali e accademici devono essere consapevoli del contenuto informativo in mostra ma, ancora di piú, della filosofia della storia che si cela dietro i pannelli e gli oggetti esposti.

_____________________

Per approfondire

- Newell, Jennifer, Libby Robin, and Kirsten Wehner. Curating the Future. Museum, Communities and Climate Change. London: Routledge, 2016.

- Egg, Markus, and Konrad Spindler. Kleidung und Ausrüstung der Gletschermumie aus den Ötztaler Alpen. Ratisbona: Schnell & Steiner, 2008.

- Brillante, Giuseppe, and C. Raffaele De Marinis. La mummia del Similaun: Ötzi, l’uomo venuto dal ghiaccio. Aneignungspraktiken an außerschulischen Lernorten. Padua: Marsilio, 1998.

Siti web

- Video: “Fernand Braudel et les différents temps de l’histoire, 30 October 1972,” Jalons Version Découverte“, (ultimo accesso 8 Settembre 2019).

- Museo Archeologico dell´Alto-Adige: http://www.iceman.it/, (ultimo accesso 8 Settembre 2019).

- Centro di Documentazione per la Storia del Nazional Socialismo: https://www.ns-dokuzentrum-muenchen.de/en/home/, (ultimo accesso 8 Settembre 2019).

_____________________

[1] See the official website of the Munich Documentation Centre for the History of National Socialism (NSDC) (ultimo accesso 8 Settembre 2019).

[2] “About the field: How do we define Public History?” National Council on Public History, https://ncph.org/what-is-public-history/about-the-field/ (ultimo accesso 8 Settembre 2019).

[3] Ronald J. Grele, “Whose Public? Whose History? What Is the Goal of a Public Historian?,” The Public Historian 3, no. 1 (Winter 1981): 46.

[4] Jill Liddington, “What Is Public History? Publics and Their Pasts, Meanings and Practices,” Oral History 30, no. 1 (Spring 2000): 89.

[5] Edward Hallet Carr, What is History? (Cambridge: University of Cambridge and Penguin Books, 1961); Fernand Braudel, On History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982); Marc Bloch, Apologie pour l’histoire ou Métier d’historien (Paris: Armand Colin, 1949); Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre, “Ai nostri lettori,” in Fernand Braudel, Problemi di metodo storico (Bari: Laterza, 1982).

[6] Benedetto Croce, Teoria e storia della storiografia (Bari: Laterza, 1916); Benedetto Croce, La storia come pensiero e come azione (Bari: Laterza, 1938).

_____________________

Image Credits

South Tyrol Archaeological Museum © 2019 Roberta Biasillo

Recommended Citation

Biasillo, Roberta: Il passato in monstra: come musealizzare la storia. In: Public History Weekly 7 (2019) 29, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-14613.

Editorial Responsibility

Isabella Schild / Thomas Hellmuth (Team Vienna)

This article reflects on the conceptualization of history embedded in museum exhibitions and discusses competing ideas of history conveyed by museums. Based on the author’s visit to the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano (Italy) and the Munich Documentation Centre for the History of National Socialism (Germany), she considers the exhibitions in the larger context of history and interpretations in museums. This piece digs into public history strategies and sheds light on the cracks between the public’s understanding and academic definitions of history.

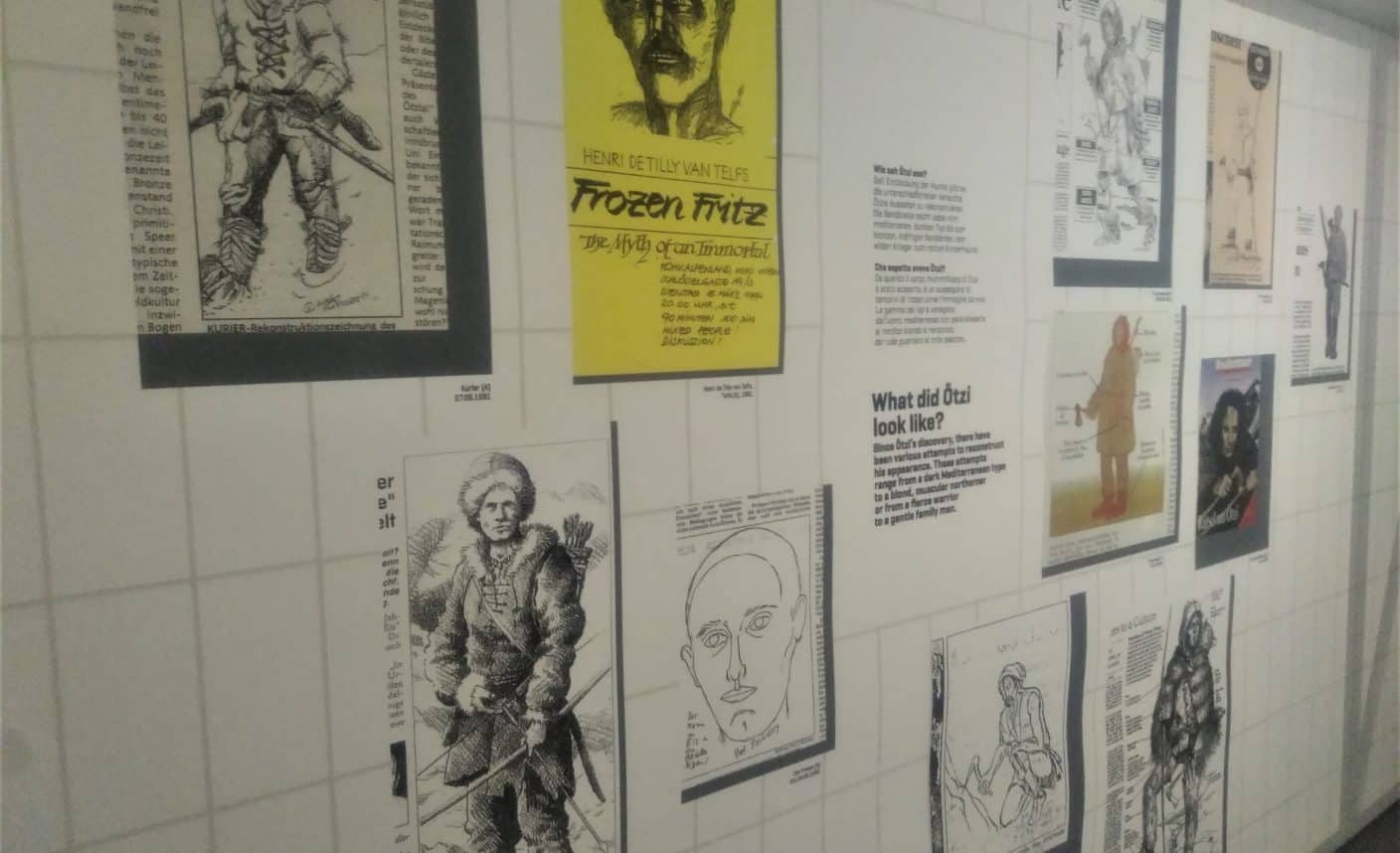

For the World’s Most Famous Glacier Mummy

Bolzano is one of the most northern Italian provincial cities, located closely to the Italian-Austrian border. Bilingual and bicultural, it is the gateway to the Dolomites, a mountain range listed amongst the UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Doubtlessly, the city’s attraction is Ötzi the iceman, a mummy kept in amazing condition for approximately 5,300 years and which was found by two German hikers in the Ötzal Alps on September 19, 1991. Based on this discovery, the Alto-Adige region has planned and built a specific museum—the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology—that since 1998 has preserved the perfectly mummified body of a prehistoric man and exposes, explains, and contextualises his personal belongings. Archaeologists, anthropologists, natural scientists, and both medical and forensic experts have contributed to an interdisciplinary exhibition; explanatory texts are captivating whilst the communication strategies are effective. Everyone I spoke with was happy, if not enthusiastic, about the visit.

Great museum, well-organised, but I felt like something was missing. How was I to make use of all this information? What is/are the lesson(s) that I, as a visitor, should have learned from this cultural space? What is its mission? Preserving a mummy is not an easy task and preserving Ötzi for future generations is surely one of the museum’s missions.

For the History of National Socialism

Historically speaking, Munich is known for its past role as capital of the Nazi movement and the borough Maxvorstadt was heavily shaped by the regime. In the very same spot where the Nazi Party had its headquarters, in 2015 the government of Bavaria inaugurated a newly constructed history museum, the Munich Documentation Centre for the History of National Socialism (NSDC). Its primary goal is to follow the development of National Socialism in Germany from its roots in the post-WWI situation to today. Beyond this specific historical phenomenon, the museum’s overarching aim is to show the fragility of and potential threats to our democracies and human right-based legal systems.

Four levels full of all kinds of information and sources and a key last section on the longue durée of Nazi ideology make this centre a living space where the documents speak to the visitors. I visited it three times over a period of one year and each time I experienced a different museum. The NSDC both inspires and warns us.

History in the World

When museum experts place the past in public fora, they assume—both explicitly and implicitly—and perform a certain idea of history or, rather, a certain philosophy of history.

In a nutshell, the first museum is an exposition of a sensational discovery, and scientists have coaxed tons of secrets from Ötzi’s 5,300-year-old body. The idea of history behind it is not the histoire événementielle since core facts allow for hypotheses around the wider context, but the corpus of information provided by this reconstruction is projected into the past. The answer to the crucial question “What can this very story tell us today?” is the missing link I was wondering about. In contrast, the central principles underlying the NSDC’s exhibition are the connection between visitors and stories on display and how to make National Socialism a matter of interest and importance to all of us.[1] The idea behind it is how to utilise history “to work in the world,”[2] to help people create and understand their own history,[3] and to elaborate on “usable pasts”.[4] In short, this museum relies on the very meaning of history as public history.

According to influential definitions given by Edward H. Carr, Fernand Braudel, Marc Bloch, and Lucien Febvre,[5] history is neither a list of events nor a description of the past. History is a multi-faceted network made up of the past, present, and future and diverse rationalities and interpretations; the here and now of the historian is central.

In my own modern-day perspective, Ötzi’s history is essentially cross-border and environmental. Italian, German, and Austrian individuals and institutions have engaged with Ötzi, and the Alps are a transnational region. Nevertheless, national borders have played a relevant role since 1991, and the contested decision to musealise the mummy in Italy was due to the fact that the corpse had lied about 90 meters within Italian territory. The 90-meter distance is something that, despite the museum’s location, reopened the issue of the relationship and cooperation among alpine countries. A section on the role that culture and history can play out in this context would be mostly welcome, as would a second element, namely a reflection on the ongoing climate change that allowed this finding. As alpine glaciers are thinning and receding, mummified bodies, rare archaeological objects, bunkers, and caves trapped in the ice are frequently emerging. Cross-border cooperation projects and Dolomite environments are nowadays as fragile as our democracies.

Why Does History Matter?

Why does history matter today and to us? This should be the core question that all history-related museums should address and answer by adopting different practices. Given that history does not coincide with the past, events and preservation and popularization efforts are necessary but not sufficient to elaborate on a historical discourse. Museums are neither archives nor libraries, but rather living spaces for the present and living beings, and displaying information is not enough and should not be enough in a period when public history is in its heyday.

If history is always contemporary, as Italian philosopher Benedetto Croce argued,[6] we need to acknowledge that history is always public since it stems from common transformations—both societal and ecological—and therefore should go public. To express the public character and mission of history more adequately, museum curators and academics need to be aware of the content on display and, more relevantly, of the hidden and deeply conceptual content behind panels and remains.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Newell, Jennifer, Libby Robin, and Kirsten Wehner. Curating the Future. Museum, Communities and Climate Change. London: Routledge, 2016.

- Egg, Markus, and Konrad Spindler. Kleidung und Ausrüstung der Gletschermumie aus den Ötztaler Alpen. Ratisbona: Schnell & Steiner, 2008.

- Brillante, Giuseppe, and C. Raffaele De Marinis. La mummia del Similaun: Ötzi, l’uomo venuto dal ghiaccio. Aneignungspraktiken an außerschulischen Lernorten. Padua: Marsilio, 1998.

Web Resources

- Video: “Fernand Braudel et les différents temps de l’histoire, 30 October 1972,” Jalons Version Découverte“, (last accessed 8 September 2019).

- South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology: http://www.iceman.it/, (last accessed 8 September 2019).

- Munich Documentation Centre for the History of National Socialism: https://www.ns-dokuzentrum-muenchen.de/en/home/, (last accessed 8 September 2019).

_____________________

[1] See the official website of the Munich Documentation Centre for the History of National Socialism (NSDC) (last accessed 13 October 2019).

[2] “About the field: How do we define Public History?” National Council on Public History, https://ncph.org/what-is-public-history/about-the-field/ (last accessed 13 October 2019).

[3] Ronald J. Grele, “Whose Public? Whose History? What Is the Goal of a Public Historian?,” The Public Historian 3, no. 1 (Winter 1981): 46.

[4] Jill Liddington, “What Is Public History? Publics and Their Pasts, Meanings and Practices,” Oral History 30, no. 1 (Spring 2000): 89.

[5] Edward Hallet Carr, What is History? (Cambridge: University of Cambridge and Penguin Books, 1961); Fernand Braudel, On History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982); Marc Bloch, Apologie pour l’histoire ou Métier d’historien (Paris: Armand Colin, 1949); Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre, “Ai nostri lettori,” in Fernand Braudel, Problemi di metodo storico (Bari: Laterza, 1982).

[6] Benedetto Croce, Teoria e storia della storiografia (Bari: Laterza, 1916); Benedetto Croce, La storia come pensiero e come azione (Bari: Laterza, 1938).

_____________________

Image Credits

South Tyrol Archaeological Museum © 2019 Roberta Biasillo

Recommended Citation

Biasillo, Roberta: The Past on Display: How to Tell History In a Museum. In: Public History Weekly 7 (2019) 29, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-14613.

Editorial Responsibility

Isabella Schild / Thomas Hellmuth (Team Vienna)

Dieser Beitrag reflektiert die Konzeptualisierung der Geschichte in Ausstellungen und thematisiert unterschiedliche Ideen von Geschichte, wie sie in Museen präsentiert werden. Ausgehend von Museumsbesuchen der Autorin im Südtiroler Archäologiemuseum in Bozen (Italien) und im NS-Dokumentationszentrum München (Deutschland) prüft sie die Ausstellungen im größeren Kontext der Geschichte und ihrer Interpretation in Museen. In diesem Artikel untersucht sie Strategien der Public History und zeigt die Diskrepanzen zwischen dem öffentlichen Verständnis und den akademischen Definitionen von Geschichte.

Für die weltberühmte Gletschermumie

Bozen ist eine der am nördlichsten gelegenen Provinzstädte Italiens nahe an der italienisch-österreichischen Grenze. Es bildet den zweisprachigen und bikulturellen Zugang zu den Dolomiten, einer beim UNESCO-Weltnaturerbe aufgelisteten Bergkette. Zweifellos ist die Hauptattraktion der Stadt Ötzi, der Mann aus dem Eis – eine Mumie, die circa 5.300 Jahre lang in erstaunlichem Zustand bewahrt und am 19. September 1991 von zwei deutschen Wanderern in den Ötztaler Alpen gefunden wurde. Anlässlich dieses Fundes hat Südtirol ein spezifisches Museum geplant und gebaut – das Südtiroler Archäologiemuseum –, das seit 1998 den perfekt mumifizierten Körper eines prähistorischen Mannes aufbewahrt und seine persönlichen Gegenstände ausstellt, erklärt und kontextualisiert. Archäolog*innen, Antropolog*innen, Naturwissenschaftler*innen und medizinische sowie forensische Expert*innen haben zu einer interdisziplinären Ausstellung beigetragen; die Begleittexte sind faszinierend und die Kommunikationsstrategien effektiv. Jeder und jede, mit der oder dem ich gesprochen habe, war mit dem Besuch zufrieden, wenn nicht gar begeistert.

Großartiges Museum, gut organisiert – aber etwas hat mir irgendwie gefehlt. Wie sollte ich all diese Informationen verarbeiten? Was ist/sind die Lehre(n), die ich als Besucherin von dieser kulturellen Einrichtung mitnehmen sollte? Was ist seine Mission? Eine Mumie aufzubewahren ist keine leichte Aufgabe und die Erhaltung von Ötzi für künftige Generationen ist bestimmt eines der Ziele des Museums.

Zur Geschichte des Nationalsozialismus

Geschichtlich gesehen ist München für seine vergangene Funktion als Hauptstadt der nationalsozialistischen Bewegung bekannt und der Stadtteil Maxvorstadt wurde von diesem Regime deutlich geformt. Genau dort, wo die Nazis ihr Hauptquartier hatten, eröffnete die bayrische Landesregierung 2015 ein neu erbautes Geschichtsmuseum, das NS-Dokumentationszentrum (NSDZ). Sein Hauptziel ist es, die Entwicklung des Nationalsozialismus in Deutschland von seinen Ursprüngen nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg bis zum heutigen Tag zu dokumentieren. Über dieses spezifische historische Phänomen hinaus hat das Museum das übergreifende Ziel, die Fragilität unserer Demokratien und menschenrechtsorientierten Rechtssystemen und die potenziellen Gefahren für sie zu zeigen.

Vier Stockwerke voll mit allen möglichen Informationen und Quellen und eine wichtige letzte Sektion über die longue durée der nationalsozialistischen Ideologie macht das Zentrum zu einem lebendigen Ausstellungsraum, wo die Dokumente zu den Besucher*innen sprechen. Ich besuchte es innerhalb eines Jahres drei Mal und jedes Mal nahm ich ein anderes Museum wahr. Das NSDZ inspiriert und warnt uns zugleich.

Geschichte in der Welt

Wenn Museumsexpert*innen die Vergangenheit in öffentlichen Foren platzieren, setzen sie – sowohl explizit als auch implizit – eine bestimmte Idee der Geschichte, oder, besser gesagt, eine bestimmte Philosophie der Geschichte, voraus und setzen sie dann um.

Alles in allem ist das Museum in Bozen eine Präsentation einer sensationellen Entdeckung, und Wissenschaftler*innen haben Ötzis 5.300-jährigen Körper jede Menge Geheimnisse entlocken können. Die Idee der Geschichte dahinter ist nicht die histoire événementielle, da die Fakten Hypothesen rund um den erweiterten Kontext erlauben, sondern, ausgehend von dieser Rekonstruktion, wird die Fülle an Informationen in die Vergangenheit projiziert. Die Antwort auf die entscheidende Frage “Was kann uns ausgerechnet diese Geschichte heute lehren?” stellt die fehlende Verbindung dar, die ich vermisst habe. Im Gegensatz dazu sichern die grundlegenden Prinzipien der NSDZ-Ausstellung die Verbindung zwischen den Besucher*innen und den ausgestellten Erzählungen und der Frage, wie der Nationalsozialismus zu einem interessanten und wichtigen Thema für jeden von uns werden kann.[1] Hinterfragt wird, wie die Geschichte verwenden werden kann, um “in der Welt zu funktionieren”,[2] um Menschen zu helfen, ihre eigene Geschichte zu schaffen und zu verstehen,[3] und um eine “brauchbare Vergangenheit” zu erarbeiten.[4] Kurz gesagt, dieses Museum stützt sich auf die reine Bedeutung der Geschichte als öffentliche Geschichte. Gemäß der Definitionen von Edward H. Carr, Fernand Braudel, Marc Bloch und Lucien Febvre[5] ist Geschichte weder eine Auflistung von Ereignissen noch eine Beschreibung der Vergangenheit. Die Geschichte ist ein vielschichtiges Netzwerk bestehend aus Vergangenheit, Gegenwart und Zukunft und diversen Rationalitäten und Interpretationen; das Hier und Jetzt der Historiker*innen ist wesentlich.

In meiner eigenen zeitgenössischen Auffassung ist die Geschichte von Ötzi praktisch grenzübergreifend und ökologisch. Italienische, deutsche und österreichische Individuen und Institutionen haben sich mit Ötzi auseinandergesetzt, und die Alpen sind eine transnationale Region. Nichtsdestotrotz haben Staatsgrenzen seit 1991 eine relevante Rolle gespielt und die umstrittene Entscheidung, die Mumie in Italien auszustellen, lag daran, dass die Leiche circa 90 Meter innerhalb des italienischen Staatsgebiets gelegen hatte. Diese 90 Meter haben trotz der Lage des Museums das Thema rund um die Beziehung und Zusammenarbeit der alpinen Länder erneut zur Diskussion gebracht. Ein Beitrag zur Rolle der Kultur und Geschichte wäre in diesem Zusammenhang sehr willkommen. Ebenso willkommen wäre ein weiteres Element, nämlich eine Reflexion über den andauernden Klimawandel, der diesen Fund ermöglicht hat. Während alpine Gletscher ausdünnen und zurückgehen, kommen im Eis gefangene mumifizierte Körper, seltene archäologische Objekte, Bunker und Höhlen immer häufiger zum Vorschein. Grenzübergreifende Kooperationen und Projekte sowie der Zustand der Dolomiten sind heutzutage so fragil wie unsere Demokratien.

Wieso ist die Geschichte von Bedeutung?

Warum ist die Geschichte – für uns – heute wichtig? Dies sollte die Kernfrage sein, die alle geschichtsorientierte Museen fragen und durch die Übernahme verschiedener Methoden beantworten sollten. Da sich die Geschichte nicht mit der Vergangenheit überschneidet, sind zwar Veranstaltungen sowie Aufbewahrungs- und Popularisierungsversuche notwendig, aber nicht genügend, um einen historischen Diskurs auszuarbeiten. Museen sind weder Archive noch Bibliotheken, sondern eher Wohnräume für die Gegenwart und lebende Menschen; die Darstellung von Informationen in einer Zeit, in der die öffentliche Geschichte eine Blütezeit erlebt, reicht nicht aus – und sollte es auch nicht.

Wenn die Geschichte immer zeitgenössisch ist, wie der italienische Philosoph Benedetto Croce argumentiert hat,[6] müssen wir erkennen, dass die Geschichte immer öffentlich ist, da sie aus gemeinschaftlichen – gesellschaftlichen wie auch ökonomischen – Transformationsprozessen besteht und daher öffentlich sein soll. Um dem öffentlichen Charakter und Auftrag der Geschichte besser gerecht zu werden, müssen sich Kurator*innen und Akademiker*innen dem ausgestellten Inhalt und – noch viel wichtiger – den versteckten Konzepten und Botschaften hinter Schautafeln und Überresten bewusst sein.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Newell, Jennifer, Libby Robin, and Kirsten Wehner. Curating the Future. Museum, Communities and Climate Change. London: Routledge, 2016.

- Egg, Markus, and Konrad Spindler. Kleidung und Ausrüstung der Gletschermumie aus den Ötztaler Alpen. Ratisbona: Schnell & Steiner, 2008.

- Brillante, Giuseppe, and C. Raffaele De Marinis. La mummia del Similaun: Ötzi, l’uomo venuto dal ghiaccio. Aneignungspraktiken an außerschulischen Lernorten. Padua: Marsilio, 1998.

Webressourcen

- Video: “Fernand Braudel et les différents temps de l’histoire, 30 October 1972,” Jalons Version Découverte“, (letzter Zugriff 8. September 2019).

- Südtiroler Archäologiemuseum: http://www.iceman.it/de/, (letzter Zugriff 8. September 2019).

- NS-Dokumentationszentrum: https://www.ns-dokuzentrum-muenchen.de/home/, (letzter Zugriff 8. September 2019).

_____________________

[1] See the official website of the Munich Documentation Centre for the History of National Socialism (NSDC) (last accessed 13 October 2019).

[2] “About the field: How do we define Public History?” National Council on Public History, https://ncph.org/what-is-public-history/about-the-field/ (letzter Zugriff 13. Oktober 2019).

[3] Ronald J. Grele, “Whose Public? Whose History? What Is the Goal of a Public Historian?,” The Public Historian 3, no. 1 (Winter 1981): 46.

[4] Jill Liddington, “What Is Public History? Publics and Their Pasts, Meanings and Practices,” Oral History 30, no. 1 (Spring 2000): 89.

[5] Edward Hallet Carr, What is History? (Cambridge: University of Cambridge and Penguin Books, 1961); Fernand Braudel, On History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982); Marc Bloch, Apologie pour l’histoire ou Métier d’historien (Paris: Armand Colin, 1949); Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre, “Ai nostri lettori,” in Fernand Braudel, Problemi di metodo storico (Bari: Laterza, 1982).

[6] Benedetto Croce, Teoria e storia della storiografia (Bari: Laterza, 1916); Benedetto Croce, La storia come pensiero e come azione (Bari: Laterza, 1938).

_____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

South Tyrol Archaeological Museum © 2019 Roberta Biasillo

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Biasillo, Roberta: Ausgestellte Vergangenheit: Wie kann Geschichte musealisiert werden. In: Public History Weekly 7 (2019) 29, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-14613.

Redaktionelle Verantwortung

Isabella Schild / Thomas Hellmuth (Team Vienna)

Copyright (c) 2019 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 7 (2019) 29

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-14613

Tags: Italy (Italien), Language: Italian, Museum, National Socialism (Nationalsozialismus), Speakerscorner

To all our non-English speaking readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 8 European languages. Just copy and paste.

This article poses an important question. When telling history in a museum it is not only the “what” which should take a great deal of consideration but more importantly is the “how”.

Biasillo describes two different examples from two different exhibitions as to how history is told based on the concept of Braudel: A histoire événementielle, which focuses on single events and the one of the longue durée, which features the development of ideas over time. Thus, rightly enhancing the connection between the exhibition of a museum and the philosophy of history that underlines it. From her two examples Biasillo clearly favours the later one. She also mentions the reason for her preference. To her history first and foremost should answer the question of “Why does history matter today and to us?”.

Thus, history in a museum should always be more than just the displaying of past events. The exhibition should provide us with a sense of understanding for our present and future situation. I would like to expand this idea from an educational perspective.

Based on the concept of Peter Gautschi (2009 in: Guter Geschichtsunterricht) the process of historical learning starts whenever an individual is confronted with an object from the universe of history. Those objects are multiple displayed in exhibitions of history museums.

Crucial for the unfolding of the next step is the asking of questions or formulating of suspicions about the object in display by the individual. The object has to be presented in an interesting light. It must arouse curiosity. Often, this process can be helped by creating a connection to the environment or living space of the visitors. Thus, answering the «to us» from Biasillo’s question.

The second step in Gautschis model contains the gathering of information about the object of curiosity. Therefore, it is crucial to not only display the object and displaying it in an interesting light, the object should also be placed in the right context and enhanced with the necessary factual information about origin, time, history etc.

The visitor should be able to correctly assign and contextualise the object – thus providing the base to make connections to former knowledge.

These connections allow us to answer the « why » of the history in display and create the foundation of connectedness to today. Visitors are now able to answer the question of “Why does history matter today and to us?” and in answering they enhance their understanding of history, open their eyes to the importance of historical studies and hopefully leave the museum with a desire to know more about this interesting subject.

Preferably the occupation with the subject leads also to a new insight into present situations and provides the impetus to act. In Biasillo’s example: to see Ötzi’s history as cross-border and environmental and to act on the given inspirations.

Whereas this educational model focuses more on the content of the exhibition, it is also important to take into considerations the different forms of displaying when talking about the « how » of history in a museum.

There are many different forms of how history can be told in a museum. The classical form of course would be things or objects. Objects like «Ötzi» which have a certain form of an aura of authenticity which triggers the interest and curiosity of the visitor. (Benjamin 1936)

Such objects can be books, clothes, cars, armour, instruments, machines and all kinds of everyday objects. In his article about material culture Andreas Ludwig differentiate between things as general description, objects which stand in contrast to the subject, artifacts where the production process is enhanced and goods that describe economical products from the consumers mindset. (Ludwig 2017)

All those things / objects can be part of the story in an exhibition. By creating the sense of the old, the original and the authentic those objects alone can bring thousands of visitors in a museum. When correctly displayed as described beforehand they will also provide the base necessary to expand their historical knowledge and broaden their educational horizon.

But depart from those classical forms of displaying museums today more and more seek new forms of storytelling. Thus, hoping to attract a different kind of visitor.

There are many new forms of exhibitions like multimedia shows, hands-on workshops, parcourse and all kind of digital elements like apps, audio-guides and augmented reality, which are on the rise in museums around the globe. (Hartung 2009)

All these new forms focus on the participation of the visitor and the triggering of emotions. Emotion is one key-point of telling history in museums. It is the component, which creates the bond between the object and subject between the history on display and the visitor.

By creating emotions, museums have an important advantage over the teaching of history in an academical context. As Biasillo writes: “Museums are neither archives nor libraries, but rather living spaces for the present and living beings”. The biggest challenge however is to create those emotions without losing the educational purpose.

————-

Literature:

– Gautschi, Peter: Guter Geschichtsunterricht: Grundlagen, Erkenntnisse, Hinweise, 2009.

– Hartung, Olaf: Aktuelle Trends in der Museumsdidaktik und ihre Bedeutung für das historische Lernen, 2009.

– Ludwig, Andreas: Materielle Kultur, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 30.05.2011.

– Walter, Benjamin: The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, 1936.