Abstract:

How should governments respond to demands for removing historic monuments and renaming sites of memory? What role could historical consciousness play with respect to these pressing demands? Given the number of recent articles in Public History Weekly on the subject,[1] my goal is not to replicate their important contributions but rather to discuss the implication for people-building and historical consciousness using Canada as a context for analysis.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-12570.

Languages: Français, English, Deutsch

Comment les gouvernements devraient-ils répondre aux demandes de retrait des monuments historiques et de changement de nom des lieux patrimoniaux? Quel rôle la théorie de la conscience historique pourrait-elle jouer dans ces débats? Puisque certains articles ont déjà été publiés sur le sujet dans Public History Weekly,[1] mon objectif est plutôt d’étudier les implications de ces débats pour le vivre-ensemble et la conscience historique en utilisant le Canada comme contexte d’analyse.

Pourquoi eux? Pourquoi maintenant?

Les monuments historiques sont d’intérêt public: de l’Afrique à l’Argentine, de l’Australie au Canada. Christophe Colomb, James Cook, Cecil Rhodes et John A. Macdonald ne se sont jamais rencontrés mais ils partagent un point en commun: ils symbolisent la nouvelle « guerre d’histoire » – une attaque publique contre de puissants personnages historiques qui symbolisent un passé contesté. Pourquoi sommes-nous en présence de cette guerre ?

1. Selon Pierre Nora, les débats actuels sont le résultat d’un profond changement dans notre rapport au passé: une « politisation générale de l’histoire ».[2] Pour Nora, les usages publics de l’histoire sont apparus au moment même où les historiens ont été témoins d’une idéologisation de leurs travaux pour des fins particulières – postcoloniales, antiracistes, politiques, etc. « Histoire et politique, comme l’affirme Nora, est l’antagonisme de l’heure, le mot politique véhiculant à la fois mémoire et idéologie ». L’antagonisme de l’histoire et de la politique a engendré de grandes questions pour la discipline historique : Quel rôle la civilisation occidentale et ses modes de penser peuvent-ils occuper dans la culture historique? Où passe la frontière entre la prise en charge des identités singulières et des identités collectives? Peut-on établir un parallèle entre le développement scientifique et la domination, entre le savoir et l’impérialisme?

2. La deuxième raison (liée à la première) est ce que Peter Seixas appelle « l’émancipation des groupes auparavant marginalisés ».[3] Un peu partout en Occident le nouveau pouvoir politique des femmes, des minorités et des peuples autochtones a forcé « un réexamen des récits historiques » et de notre conception même de l’ « Histoire » comme étalon de mesure historique. Les personnes et les sujets traditionnellement jugés marginaux occupent désormais une place centrale. Inversement, l’importance des « grands hommes » a été sérieusement contestée. Cette redéfinition ne pouvait se produire que dans une ère séculière et post-nationale puisque les paradigmes théologiques et nationaux fournissaient auparavant les orientations et les critères de jugement historique.

3. Enfin, la mondialisation et les technologies qui y sont associées ont non seulement permis au monde de communiquer plus facilement mais ont également fourni des moyens supplémentaires aux individus – qu’ils soient éduqués et non – pour exprimer librement leurs opinions. Du Printemps arabe de 2010 aux tweets du Président Trump sur les monuments confédérés, les technologies de la communication ont changé, certaines diront perturbées, notre relation au pouvoir.[4]

Les monuments comme sites de la conscience historique

Comme Thomas Cauvin le soutient, le traitement des monuments comme lieux de mémoire est une question complexe en raison des opinions passionnées et des multiples contextes dans lesquels ces débats ont lieu.[5] Par exemple, le débat entourant le monument commémoratif de Sir John A. Macdonald, premier ministre du Canada et architecte du système des pensionnats pour assimiler les Autochtones, est différent de celui traitant du Commandant confédéré Robert E. Lee ou du magnat britannique Cecil Rhodes. Mais tous pourraient bénéficier d’une conscience historique réfléchie plutôt que la politisation générale de l’histoire.

Pour analyser le rôle de la conscience historique, il est utile de débuter par une réflexion conceptuelle sur les sites de mémoire. Seixas et Lévesque ont récemment proposé des modèles d’analyser la relation entre l’histoire et la mémoire, qui peuvent servir de base à la discussion.[6] Ces « matrices » de sens ont été transposées comme suit pour notre analyse.

– Culture historique: Les lieux de mémoire sont intégrés au sein de cultures historiques qui englobent la totalité des discours par lesquels une société se comprend et se raconte son passé et son devenir. Ainsi, les lieux de mémoire documentent non seulement les aspects des cultures passées mais aussi nos propres mémoires contemporaines en rapport avec ces lieux.

– Culture et pratique de la vie: Les lieux de mémoire jouent un rôle important dans la société puisque les citoyens font appel à ces éléments pour produire des récits, orienter leur vie personnelle et forger leur identité ce qui, par le fait même, nourrit la mémoire collective et la construction de communautés d’appartenance. Comme les monuments existent dans un contexte avec une certaine ambigüité inhérente au passé et à leur finalité, plusieurs récits peuvent ainsi être générées au fil du temps.[7] Les usages publics du passé (issus d’heuristique intuitives) sont ne sont pas régulées par des « méthodes scientifiques et une réflexion méthodologique ».[8]

– Histoire disciplinaire: Le rôle des lieux de mémoire est étudié par le biais de la recherche et d’une analyse historique. Les grandes questions sociétales (par ex., devrions-nous enlever des monuments?) génèrent des questions qui sont examinées par le biais d’un processus intellectuel rigoureux et fondé en preuve. Les outils de la pensée historique sont alors utilisés pour arriver « de manière indépendante à des avis raisonnables et éclairés », ouverts aux discussions et à la critique.[9] Ces représentations narratives du passé sont ensuite réintroduites dans la culture.

Compétences de la conscience historique

Si nous considérons la conscience historique comme une structure mentale d’appréhension et de compréhension de la culture historique, nous pouvons éventuellement articuler un ensemble de dimensions pour traiter des lieux de mémoire de manière plus efficace et raisonnée.[10] A partir des travaux de Jörn Rüsen, Andreas Körber et d’autres, nous pouvons proposer les compétences suivantes en guise de conclusion (voir la figure):

– Compétence d’enquête: habiletés à élaborer des questions et à mener des enquêtes de nature historique (Pourquoi le Canada possède-t-il des monuments? Qui les a créés? Que devrions-nous faire des monuments de Macdonald? Quelles sources peuvent me fournir des réponses? Quelle est la fiabilité de ces sources?)

– Compétence de la pensée historique: habiletés à répondre aux questions en utilisant les concepts clés (Pourquoi se souvient-on de Macdonald? Pour quelles raisons a-t-on créé des monuments en son honneur? Qu’est-ce qui a changé/est demeuré pareil depuis leur création? Dans quel contexte Macdonald vivait-il? Comment les gens de l’époque réagissaient-ils à ses idées et ses politiques? Selon quelles normes devrions-nous juger les actions de Macdonald? En quoi ces normes sont-elles universelles/culturellement enracinées?)

– Compétence d’orientation: habiletés à relier les informations et les récits historiques à sa propre vie (que puis-je apprendre des actions de Macdonald? Quelle obligation ai-je envers Macdonald et son héritage? En quoi mon point de vue sur Macdonald est-il affecté ou non par la culture historique et la communauté dans laquelle je vis?)

– Compétence narrative: habiletés à créer, lire et comprendre la structure des récits historiques (Quelle est la structure des récits? Quelles fonctions occupent les récits dans la culture? Quels récits de Macdonald pouvons-nous écrire? Quelle est la validité de ces récits? Quels jugements de valeur contiennent-ils? Comment évaluer les récits et selon quels critères?)

_____________________

Littérature complémentaire

- Ercikan, Kadriye, and Peter Seixas, eds. New Directions in Assessing Historical Thinking. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Munslow, Alun. Narrative and History. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Liens externes

- Active History.ca, History Matters (Indigenous Blog series): https://activehistory.ca (consulté le 24 Septembre 2018).

- American Historical Association, Historians on the Confederate Monument Debate: https://www.historians.org/historians-on-the-confederate-monument-debate (consulté le 24 Septembre 2018)

_____________________

[1] Voir Robert Parkes, “Are Monuments History?,” Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 34, dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10215; Thomas Cauvin, “Controversies over Monuments: An Opportunity for International Public History,” Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 42, dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10685; Chantal Kesteloot, “Charlottesville et le passé controversé dans l’espace public belge,” Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 42, http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10729; et Krzysztof Ruchniewicz, “Yet Another Memorial in Berlin?,” Public History Weekly 6 (2018) 20, dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-12161.

[2] Pierre Nora, “Recent history and the new dangers of politicization,” Eurozine, November 2011, https://www.eurozine.com/recent-history-and-the-new-dangers-of-politicization/ (consulté le 24 Septembre 2018).

[3] Peter Seixas, “The Purposes of Teaching Canadian History,” Canadian Social Studies 36, 2 (2002), http://historicalthinking.ca/sites/default/files/files/docs/The%20Purposes%20of%20Teaching%20Canadian%20History.pdf. (consulté le 24 Septembre 2018).

[4] Jeremy Heimans and Tim Dixon, “Technology is a great tool – but it is people that will change politics,” The Guardian, June 26, 2011, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2011/jun/26/politics-change-new-technology; Paul Armstrong, “How Technology Is Really Going To Change Politics In The Next 20 Years,” Forbes, March 1, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/paularmstrongtech/2018/03/01/how-technology-is-really-going-to-change-politics-in-the-next-20-years/#2dfd95981eb3 (consulté le 24 Septembre 2018).

[5] Concernant les lieux de mémoire (realms of memory), voir Pierre Nora (dir.). Les lieux de mémoire 3 tomes (Gallimard, 1984, 1986, 1992).

[6] Peter Seixas, “A History/Memory Matrix for History Education,” Public History Weekly 4 (2015) 6, dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-5370; and Stephane Lévesque, “Going beyond “Narratives” vs. “Competencies”: A model for understanding history education,” Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 12, dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-5918.

[7] Comme le soutient Parkes, les monuments et les sites patrimoniaux ne sont pas muets et figés dans le temps. Ils doivent être lus comme des « textes » qui nous parlent de façons différentes et qui documentent le contexte historique de l’époque dans laquelle ils ont été créés. En ce sens, plusieurs récits peuvent êtres produits à partir de ces mêmes lieux de mémoire.

[8] Andreas Körber, Historical consciousness, historical competencies – and beyond? Some conceptual development within German history didactics (Frankfurt am Main: pedocs, 2015), urn:nbn:de:0111-pedocs-108118.

[9] Peter Seixas, “Schweigen! die Kinder! or does postmodern history have a place in the schools?,” in Knowing, teaching, and learning history: National and international perspectives, eds. Peter N. Stearns, Peter Seixas and Sam Wineburg (New York: New York University Press, 2000), 25.

[10] A ce chapitre, deux publications canadiennes récentes sont d’intérêt: Viviane Gosselin and Phaedra Livingstone, Museums and the Past: Constructing Historical Consciousness (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2016) and Stephanie Anderson, “The Stories Nations Tell: Sites of Pedagogy, Historical Consciousness, and National Narratives,” Canadian Journal of Education 40, 1 (2017). http://journals.sfu.ca/cje/index.php/cje-rce/article/view/2143 (consulté le 24 Septembre 2018).

_____________________

Crédits Illustration

John A. Macdonald statue – Queen’s Park, Toronto © CC0 1.0 Daderot via Wikimedia.

Citation recommandée

Lévesque, Stéphane: Déboulonner le “passé”: les sites officiels de la mémoire. In: Public History Weekly 6 (2018) 29, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-12570.

How should governments respond to demands for removing historic monuments and renaming sites of memory? What role could historical consciousness play with respect to these pressing demands? Given the number of recent articles in Public History Weekly on the subject,[1] my goal is not to replicate their important contributions but rather to discuss the implication for people-building and historical consciousness using Canada as a context for analysis.

Why them? Why now?

Historic monuments are making news around the world: from South Africa to Argentina, from Australia to Canada. Christopher Columbus, James Cook, Cecil Rhodes, and John A. Macdonald never met one another but they all share something in common: they symbolize the new history war – a frontal public attack on powerful historical male figures who represent contested narratives of the collective past. Why is this happening now?

1. According to Pierre Nora, the actual debates are the result of a profound change in our common approach to the past: the “general politicization of history”.[2] For Nora, popular interests in history emerged at the same moment when historians’ works were being transformed into ideologies for particular claims about the past – postcolonial, anti-racist, political, etc. “History versus politics,” Nora contends, “is today’s conflict, and the word ‘politics’ covers both memory and ideology.” This new antagonistic pair has led to profound questions for the discipline: What role should Western civilization and its associated modes of thinking (including history) play in historical culture? Where does the boundary lie between vernacular and group identities? Is there a parallel between scientific development and domination, between knowledge and forms of imperialism?

2. The second reason (related to the first one) is what Peter Seixas calls the “empowerment of previously disempowered groups”.[3] In South Africa, the Americas, Europe, and other places, the new political power of women, ethnic minorities, and Aboriginal peoples has forced “a re-examination of the stories of the past” as well as what counts as “history”. People and subjects traditionally deemed insignificant of study now occupy centre-stage. Conversely, the prominence of the “great men” has been disputed seriously. As Seixas contends, this redefinition could only arise in a secular, post-national era because theological and nation-building paradigms conventionally provided the direction and meaning for the inclusion of events/people into master-narratives.

3. Finally, globalization and its associated technologies have not only brought people from around the world into communication with each other, but also provided additional means for individuals – the educated and the uneducated – to voice their opinion. From the Arab Spring of 2010 to President Trump’s tweets on the Confederate monuments, communication technologies have altered – some might say disrupted – our relation to power.[4]

Monuments as Sites of Historical Consciousness

Dealing with monuments, as Thomas Cauvin contends, is a complex issue due to the impassionate public opinions and the multiple contexts in which these debates take place. For example, the Canadian memorial issue over the fate of Sir John A. Macdonald, first prime minister of Canada and architect of the residential school system for assimilating Aboriginal peoples, is different from the ones dealing with Confederate Commander Robert E. Lee or British magnate Cecil Rhodes. But all could benefit from competencies of historical consciousness as opposed to general politicization.

In order to analyze the role of historical consciousness, it is useful to begin with a conceptual way of thinking about monuments as realms of memory.[5] Both Seixas and Lévesque have recently offered complementary frameworks on the relationship between history and memory which can serve as a basis for discussion.[6] These “matrices” have been transposed as follow for our analysis.

– Historical culture: Monuments and sites of memory are embedded into distinctive historical cultures which encompass the totality of discourses in which a society understands itself and its future by narrating the past. These lieux de mémoire (realms of memory) document not only aspect of past historical cultures but our own memory reactions in the present as members of given cultures.

– Culture and life practice: Monuments and sites of memory play important functions in society. People rely on these to produce narratives for life purposes, orientation, and identity formation, which, in turn, inform public memories and community building through the mechanism of cadres sociaux (social frames). As monuments exist in context with an inherent ambiguity about the past and their purpose, multiple stories can be generated over time.[7] Practical approaches to the past (everyday mental heuristics) poorly regulated by “valid methods and methodological reflection” tend to govern historical thinking process.[8]

– Disciplinary history: The roles and functions of realms of memory are studied through scholarly historical research and discourse. Societal issues (e.g., should we remove monuments?) generate research questions which are investigated through an intellectually rigorous evidence-based process. Historical thinking tools are used to arrive “independently at reasonable, informed opinions” open to further discussion and criticism.[9] These narrative representations of the past are reintroduced into historical culture and generate additional questions and demands.

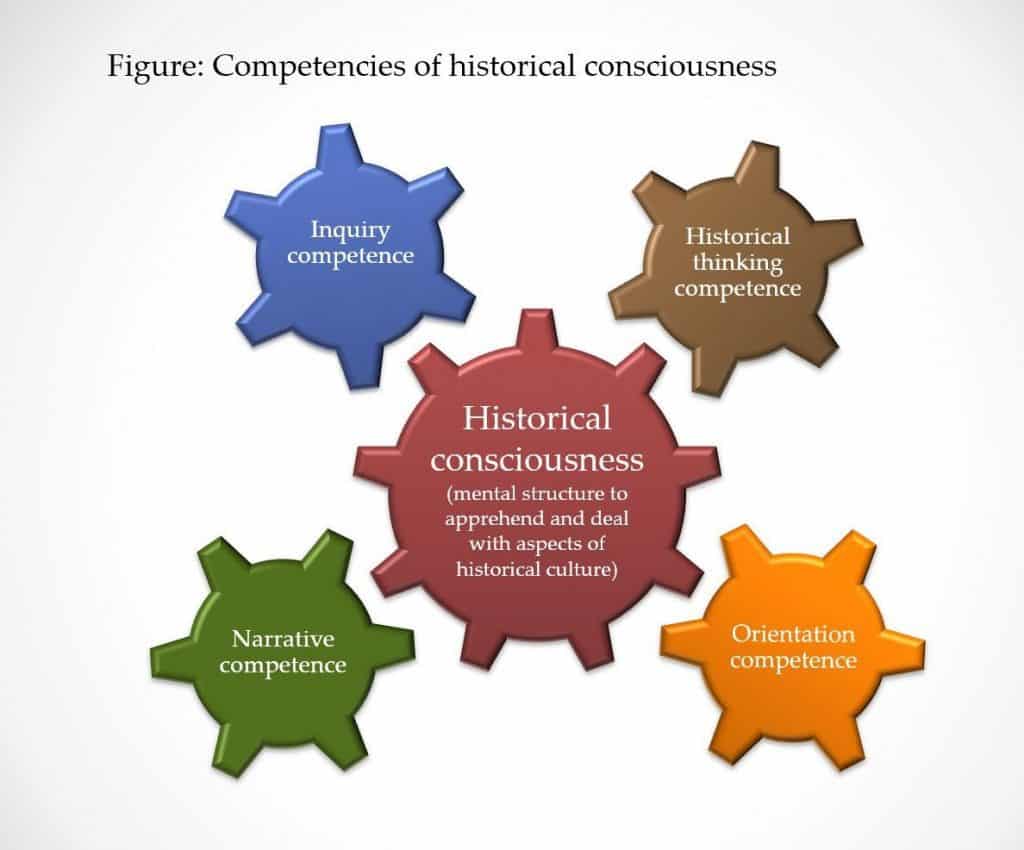

Competencies of Historical Consciousness

If we consider historical consciousness as the mental structure that underlies our understanding and dealing with important aspects of historical culture, then we can possibly articulate a set of dimensions to deal with monuments.[10] From the works of Jörn Rüsen, Andreas Körber, and others, we can infer the following competencies as a conclusion for further discussion (see figure):

– Inquiry competence: Ability to devise historical questions and engage in evidence-based investigation (Why does Canada have monuments? Who created them? What should we do with monuments of Macdonald? What sources can tell me something about the issue? How can I evaluate the value/credibility of these sources?)

– Historical thinking competence: Ability to think historically about the issue using key concepts (What makes Macdonald significant to remember? For whom? Why were monuments created for him? What has changed/remained the same since their creation? What was the context in which Macdonald lived? How did people at the time react to Macdonald’s ideas/policies? Under what standards should we judge Macdonald’s actions? How are these standards universal/culturally-bound?)

– Orientation competence: Ability to relate information and narratives about the past into one’s own practical life (What can I/we learn from Macdonald’s life? What obligation do I/we have to Macdonald and his legacy? How do monuments affect my views about the past/future? How are my views shaped by the larger historical culture in which I live?)

– Narrative competence: Ability to read, create, and understand the structure of historical narratives (How are historical narratives constructed? What functions do they play in culture? What narratives about Macdonald can we create? How plausible are these narratives? What value judgments do they hold? How can we adjudicate between competing narratives? On what empirical/normative ground?)

_____________________

Further Reading

- Ercikan, Kadriye, and Peter Seixas, eds. New Directions in Assessing Historical Thinking. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Munslow, Alun. Narrative and History. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Web Resources

- Active History.ca, History Matters (see Indigenous Blog series): https://activehistory.ca (last accessed 24 September 2018).

- American Historical Association, Historians on the Confederate Monument Debate: https://www.historians.org/historians-on-the-confederate-monument-debate (last accessed 24 September 2018)

_____________________

[1] See Robert Parkes, “Are Monuments History?,” Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 34, dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10215; Thomas Cauvin, “Controversies over Monuments: An Opportunity for International Public History,” Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 42, dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10685; Chantal Kesteloot, “Charlottesville et le passé controversé dans l’espace public belge,” Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 42, http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10729; and Krzysztof Ruchniewicz, “Yet Another Memorial in Berlin?,” Public History Weekly 6 (2018) 20, dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-12161.

[2] Pierre Nora, “Recent history and the new dangers of politicization,” Eurozine, November 2011, https://www.eurozine.com/recent-history-and-the-new-dangers-of-politicization/ (last accessed 24 September 2018).

[3] Peter Seixas, “The Purposes of Teaching Canadian History,” Canadian Social Studies 36, 2 (2002), http://historicalthinking.ca/sites/default/files/files/docs/The%20Purposes%20of%20Teaching%20Canadian%20History.pdf. (last accessed 24 September 2018).

[4] Jeremy Heimans and Tim Dixon, “Technology is a great tool – but it is people that will change politics,” The Guardian, June 26, 2011, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2011/jun/26/politics-change-new-technology; Paul Armstrong, “How Technology Is Really Going To Change Politics In The Next 20 Years,” Forbes, March 1, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/paularmstrongtech/2018/03/01/how-technology-is-really-going-to-change-politics-in-the-next-20-years/#2dfd95981eb3 (last accessed 24 September 2018).

[5] On the notion of lieux de mémoire (realms of memory), see Pierre Nora and Lawrence D. Kritzman, Realms of Memory: The Construction of the French Past (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997).

[6] Peter Seixas, “A History/Memory Matrix for History Education,” Public History Weekly 4 (2015) 6, dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-5370; and Stephane Lévesque, “Going beyond “Narratives” vs. “Competencies”: A model for understanding history education,” Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 12, dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-5918.

[7] As Parkes rightly notes, monuments and sites of memory are not fixed and silent, they are “texts” documenting something about the historical culture of the time commemorated as well as the time in which they were created. As such, they convey more than one single narrative meaning about the past (Celebrate? Provoke? Proclaim?).

[8] Andreas Körber, Historical consciousness, historical competencies – and beyond? Some conceptual development within German history didactics (Frankfurt am Main: pedocs, 2015), urn:nbn:de:0111-pedocs-108118.

[9] Peter Seixas, “Schweigen! die Kinder! or does postmodern history have a place in the schools?,” in Knowing, teaching, and learning history: National and international perspectives, eds. Peter N. Stearns, Peter Seixas and Sam Wineburg (New York: New York University Press, 2000), 25.

[10] Two recent Canadian publications on historical consciousness and memory practices are worthy of mention: Viviane Gosselin and Phaedra Livingstone, Museums and the Past: Constructing Historical Consciousness (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2016) and Stephanie Anderson, “The Stories Nations Tell: Sites of Pedagogy, Historical Consciousness, and National Narratives,” Canadian Journal of Education 40, 1 (2017). http://journals.sfu.ca/cje/index.php/cje-rce/article/view/2143 (last accessed 24 September 2018).

_____________________

Image Credits

John A. Macdonald statue – Queen’s Park, Toronto © CC0 1.0 Daderot via Wikimedia.

Recommended Citation

Lévesque, Stéphane: Removing the “Past”: Debates Over Official Sites of Memory. In: Public History Weekly 6 (2018) 29, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-12570.

Wie sollen Regierungen mit den Forderungen, historische Denkmäler zu entfernen und Erinnerungsorte umzubenennen, umgehen? Welche Rolle könnte Geschichtsbewusstsein in diesen Debatten spielen? In Anbetracht der verschiedenen Artikel, die unlängst auf Public History Weekly publiziert wurden,[1] liegt es mir fern, diese wichtigen Beiträge zu replizieren. Vielmehr werde ich die daraus erfolgenden Implikationen für das gesellschaftliche Zusammenleben und das Geschichtsbewusstsein diskutieren, indem ich Kanada als Analysekontext verwende.

Warum diese? Warum jetzt?

Gegenwärtig wird global über historische Denkmäler diskutiert: von Südafrika über Argentinien bis nach Australien, Amerika und Kanada. Christoph Kolumbus, James Cook, Cecil Rhodes und John A. Macdonald sind sich nie begegnet, dennoch haben sie etwas gemeinsam: Sie symbolisieren den neuen “Geschichtskrieg” – ein Frontalangriff auf mächtige männliche historische Figuren, die umkämpfte Narrative der kollektiven Vergangenheit repräsentieren. Warum geschieht das gerade jetzt?

1. Laut Pierre Nora resultieren die aktuellen Debatten aus einem profunden Wechsel der Form, wie wir uns der Vergangenheit annähern: Dabei handelt es sich um eine “allgemeine Politisierung von Geschichte”.[2] Für Nora gewinnt der öffentliche Gebrauch von Geschichte immer dann an Popularität, wenn die Arbeit von Historiker*innen in Ideologien für spezifische Ansprüche an die Vergangenheit genutzt wurden – seien diese Ansprüche postkolonial, antirassistisch oder politisch. “Als Antagonismus ‘Geschichte versus Politik’”, so Nora, ”stellt sich der heutige Konflikt dar, wobei das Wort ‘Politik’ sowohl Erinnerung als auch Ideologie impliziert”. Dieses neue widerstreitende Paar evozierte grundsätzliche Fragen an die Disziplin: Welche Rolle sollte die westliche Gesellschaft und ihre Mentalität in der Geschichtskultur spielen? Wo verläuft die Grenze zwischen der Vereinnahmung individueller und sozialer Identität? Existiert eine Parallele zwischen wissenschaftlicher Entwicklung und Herrschaft, zwischen Wissen und Macht?

2. Der zweite Grund ist das, was Peter Seixas “Die Emanzipation von früher entmachteten Gruppen” nennt.[3] In Südafrika, Amerika, Europa und andernorts hat die neue politische Macht von Frauen, ethnischen Minderheiten und indigenen Bevölkerungsgruppen nolens volens dazu geführt, nicht nur “die Erzählungen über die Vergangenheit erneut zu prüfen”, sondern auch zu überlegen, was valide “Geschichte” sei. Bisher vernachlässigte Bevölkerungsgruppen rücken allmählich in den Fokus der Forschung. Umgekehrt bedeutet dies, dass die Relevanz der “Grossen Männer” ernsthaft angezweifelt wird. Laut Seixas besteht ein Zusammenhang zwischen dem Aufkommen dieser Neudefinierung und einer säkularen post-nationalen Ära, denn in den vorhergehenden theologischen und nationsbildenden Phasen mussten Menschen und Ereignisse gewöhnlich in ein Masternarrativ gepasst werden.

3. Letztlich führten die Globalisierung und die damit entstandenen neuen Technologien nicht nur dazu, dass Menschen aus aller Welt miteinander kommunizieren können, sondern sie bieten Individuen – sowohl bildungsnahen als auch bildungsfernen – die Möglichkeit, ihre Stimmen zu erheben: vom Arabischen Frühling 2010 bis hin zu Trumps Tweets zu den Denkmälern der Konföderierten. Kommunikationstechnologien haben unsere Beziehungen zu Macht verändert, wenn nicht gar durcheinandergebracht.[4]

Denkmäler als Orte von Geschichtsbewusstsein

Die Auseinandersetzung mit Denkmälern als Erinnerungsorte ist laut Thomas Cauvin eine komplexe Angelegenheit, gibt es zu diesen in der Öffentlichkeit doch divergierende Meinungen, die in den heterogensten Kontexten diskutiert werden. Das Beispiel Sir John A. Macdonald, erster Premierminister Kanadas und Architekt des Internatsschulsystems, das die Assimilierung der indigenen Bevölkerung an den weissen Mainstream bezweckte, wird anders verhandelt als das Beispiel Robert E. Lee, General des konföderierten U.S.-Heeres, oder das des britischen Magnaten Cecil Rhodes. Alle drei Auseinandersetzungen jedoch könnten profitieren, wenn anstelle einer generellen Politisierung ein reflektiertes Geschichtsbewusstsein zum Zuge käme.

Um die Rolle des Geschichtsbewusstseins in diesen Debatten zu analysieren, erweist es sich als hilfreich, konzeptionell über Geschichte und Erinnerung nachzudenken.[5] Sowohl Seixas als auch Lévesque haben unlängst Modelle zum Studium der Beziehung zwischen Geschichte und Erinnerung vorgeschlagen, welche als Basis für die hier zu führende Diskussion dienen können.[6] Diese Matrizes wurden unserer Analyse wie folgt zu Grunde gelegt:

– Geschichtskultur: Denkmäler und Erinnerungsorte werden in distinkte Geschichtskulturen integriert, die einen holistischen Diskurs umfassen, über welchen sich eine Gesellschaft definiert und sowohl ihre Vergangenheit als auch ihre Zukunft verhandelt. Zudem dokumentieren diese Erinnerungsorte nicht nur die kulturellen Aspekte der Vergangenheit, sondern auch die zeitgenössischen Impulse, die aus dem Prozess des kollektiven Erinnerns hervorgehen.

– Kultur und Lebenspraxis: Denkmäler und Erinnerungsorte spielen eine wichtige Rolle in der Gesellschaft, die sich auf diese bezieht, um sinnstiftende Narrative für das Leben, kulturelle Orientierung und Identitätskonstruktionen zu etablieren. Diese speisen in der Umkehr das kollektive Gedächtnis und definieren über die Mechanismen der sozialen Bedingungen die Zugehörigkeit zu einer Gemeinschaft. Da Denkmälern multilaterale Vergangenheitsdeutungen und damit verknüpft heterogene Entstehungskontexte innewohnen, können aus ihnen im Verlaufe der Zeit verschiedene Narrative entwickelt werden.[7] Der öffentliche Gebrauch von Geschichte ist nicht durch wissenschaftliche Methoden und deren Reflexion reguliert.[8]

– Geschichtswissenschaft: Die Rolle und Funktionen von Erinnerungsorten werden durch historiographische Forschung und den damit verbundenen Diskurs analysiert. Gesellschaftliche Auseinandersetzungen (z.B. ob bedeutende Denkmäler entfernt werden sollen) evozieren Forschungsfragen, welche in einem wissenschaftlichen, rigoros quellenbasierten Prozess untersucht werden. In diesem Kontext werden geschichtswissenschaftliche Analyseinstrumente benutzt, um “auf unabhängige Weise vernunftorientierte und fundierte Meinungen” zu entwickeln, welche Diskussionen und Kritik zur Verfügung stehen.[9] Diese von der Wissenschaft zur Verfügung gestellten Vergangenheitsnarrative werden wieder in die Geschichtskultur eingeführt, wo sie zusätzliche Fragen und Forderungen generieren können.

Kompetenzen des Geschichtsbewusstseins

Wenn wir Geschichtsbewusstsein als eine mentale Struktur in Betracht ziehen, die unserem Verständnis von sowie der Auseinandersetzung mit Geschichtskultur zugrunde liegt, können wir möglicherweise Dimensionen identifizieren, die einen reflektierteren Umgang mit Erinnerungsorten ermöglichen.[10] Von den Arbeiten von Jörn Rüsen, Andreas Körber und anderen können wir folgende Kompetenzen als Konklusionen für weitere Diskussionen ableiten (siehe Abbildung):

– Erkundungskompetenz: Fähigkeit, historisch relevante Fragen zu stellen und geschichtswissenschaftliche Untersuchungen durchzuführen (Wer hat in Kanada Denkmäler errichtet und warum? Was soll mit Denkmälern von Macdonald geschehen? Welche Quellen können zur Beantwortung der Fragen hilfreich sein? Wie steht es um die Vertrauenswürdigkeit dieser Quellen?)

– Kompetenz zum historischen Denken: die Fähigkeit, anhand Schlüsselkompetenzen geschichtswissenschaftlich zu reflektieren und Antworten auf die gestellten Fragen zu geben (Warum und für wen ist Macdonald erinnerungswürdig? Was war der Kontext seiner Lebenswelten? Wie wurden seine Ideen, seine Politik von der Gesellschaft aufgenommen? Nach welchen Normen sollen wir seine Handlungen beurteilen? Inwiefern sind diese Normen universell oder kulturell verankert?)

– Orientierungskompetenz: Fähigkeit, Informationen und Narrative über die Vergangenheit seinem eigenen Lebensalltag zuzuordnen (Was kann ich aus den Handlungen von Macdonald lernen? Welche Verpflichtungen habe ich in Bezug auf Macdonald und seinem Erbe? Wie beeinflussen Denkmäler meine Einstellung zur Vergangenheit und zur Zukunft? Wie wird meine Einstellung von der Mehrheitskultur, in der ich sozialisiert wurde, geformt?)

– Narrative Kompetenz: Fähigkeit, Strukturen von historischen Narrativen zu lesen, zu entwickeln und zu verstehen (Wie werden Narrative konstruiert? Welche Rolle spielen diese in der Kultur? Welche Narrative können wir über Macdonald erzählen? Sind dies Narrative plausibel? Welche Werturteile enthalten diese Narrative? Wie können diese Narrative beurteilt werden und mit welchen Kriterien soll dies geschehen?)

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Ercikan, Kadriye, and Peter Seixas, eds. New Directions in Assessing Historical Thinking. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Munslow, Alun. Narrative and History. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Webressourcen

- Active History.ca, History Matters (siehe die Indigenous-Blog-Serie): https://activehistory.ca (letzter Zugriff 24. September 2018).

- American Historical Association, Historians on the Confederate Monument Debate: https://www.historians.org/historians-on-the-confederate-monument-debate (letzter Zugriff 24. September 2018).

_____________________

[1] Siehe Robert Parkes, “Are Monuments History?,” Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 34, dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10215; Thomas Cauvin, “Controversies over Monuments: An Opportunity for International Public History,” Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 42, dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10685; Chantal Kesteloot, “Charlottesville et le passé controversé dans l’espace public belge,” Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 42, http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10729; und Krzysztof Ruchniewicz, “Yet Another Memorial in Berlin?,” Public History Weekly 6 (2018) 20, dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-12161.

[2] Pierre Nora, “Recent history and the new dangers of politicization,” Eurozine, November 2011, https://www.eurozine.com/recent-history-and-the-new-dangers-of-politicization/ (letzter Zugriff 24. September 2018).

[3] Peter Seixas, “The Purposes of Teaching Canadian History,” Canadian Social Studies 36, 2 (2002), http://historicalthinking.ca/sites/default/files/files/docs/The%20Purposes%20of%20Teaching%20Canadian%20History.pdf. (letzter Zugriff 24. September 2018).

[4] Jeremy Heimans and Tim Dixon, “Technology is a great tool – but it is people that will change politics,” The Guardian, June 26, 2011, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2011/jun/26/politics-change-new-technology; Paul Armstrong, “How Technology Is Really Going To Change Politics In The Next 20 Years,” Forbes, March 1, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/paularmstrongtech/2018/03/01/how-technology-is-really-going-to-change-politics-in-the-next-20-years/#2dfd95981eb3 (letzter Zugriff 24. September 2018).

[5] On the notion of lieux de mémoire (realms of memory), see Pierre Nora and Lawrence D. Kritzman, Realms of Memory: The Construction of the French Past (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997).

[6] Peter Seixas, “A History/Memory Matrix for History Education,” Public History Weekly 4 (2015) 6, dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-5370; and Stephane Lévesque, “Going beyond “Narratives” vs. “Competencies”: A model for understanding history education,” Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 12, dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-5918.

[7] Wie Parkes richtig bemerkte, Monumente und Erinnerungsorte sind nicht starr und schweigend, sie sind «Texte», welche sowohl etwas über die Geschichtskultur der zeitgenössischen Erinnerungskultur als auch über die Zeit, in der sie errichtet wurde, verlauten lassen. In diesem Sinne vermitteln sie mehr als nur ein Vergangenheitsnarrativ (Zelebration? Provokation? Proklamation?)

[8] Andreas Körber, Historical consciousness, historical competencies – and beyond? Some conceptual development within German history didactics (Frankfurt am Main: pedocs, 2015), urn:nbn:de:0111-pedocs-108118.

[9] Peter Seixas, “Schweigen! die Kinder! or does postmodern history have a place in the schools?,” in Knowing, teaching, and learning history: National and international perspectives, eds. Peter N. Stearns, Peter Seixas and Sam Wineburg (New York: New York University Press, 2000), 25.

[10] Zwei aktuelle kanadische Publikationen über historisches Gewissen und Erinnerungspraxis sollen hier eigens erwähnt werden: Viviane Gosselin and Phaedra Livingstone, Museums and the Past: Constructing Historical Consciousness (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2016) and Stephanie Anderson, “The Stories Nations Tell: Sites of Pedagogy, Historical Consciousness, and National Narratives,” Canadian Journal of Education 40, 1 (2017). http://journals.sfu.ca/cje/index.php/cje-rce/article/view/2143 (letzter Zugriff 24. September 2018).

_____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

John A. Macdonald statue – Queen’s Park, Toronto © CC0 1.0 Daderot via Wikimedia.

Translation

Translated by Rachel Huber

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Lévesque, Stéphane: “Vergangenheit” entfernen: Debatten über staatliche Erinnerungsorte. In: Public History Weekly 6 (2018) 29, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-12570.

Copyright (c) 2018 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 6 (2018) 29

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-12570

Tags: History Politics (Geschichtspolitik), Language: French, Monument (Denkmal)

To all our non-English speaking readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator. Just copy and paste.

Stephane, thanks for getting this discussion started.

19th century monuments are an anachronistic medium. It is only when they become sites of battles over the control of history culture that they are even noticed. Right now, their anachronism has made them a rallying point for those who are uncomfortable with demographic and cultural change, and what those changes might mean for power relations.

I am not sure what your question is regarding monuments. Is it that we should encourage a public discourse that is in the tenor of what Rüsen would call genetic historical consciousness? I would argue that the current discourse around, for example, Confederate monuments in the U.S. South, is evidence of sophisticated, if not always “genetic” historical consciousness.

In my experience in Richmond Virginia (former capital of the Confederacy), the public discourse among supporters of maintaining Confederate monuments is mostly characterized by an exemplary stance – these statues represent my heritage, which it is my moral duty to defend because my heritage is at stake. Among those who want them removed, the discourse is generally exemplary as well – these statues are offensive and should be removed, to critical – these statues reinstate a connection to a white supremacist past that we want to negate today. Generally, it is only historians that argue from a genetic stance – we should place plaques with information about the white supremacists who put these statues up after they regained power.

What we must contend with is that the genetic stance, nuanced epistemologically and contextualized by deep historical knowledge, is unsatisfying politically. Politics is a pretty important aspect of the orientation competence, so the simplistic politics vs. history is not a useful framework for helping history educators or their students to grapple with the presence of monuments that valorize oppressors in our public spaces.

I think Nora’s argument about the changing relationship of history the discipline, and “politics” is unconvincing as well. His primary focus is on French historiography, a topic I am wholly unqualified to comment on, so I won’t. However, since in the Enlightenment tradition he speaks universally, I do feel qualified to question what his point really is. He makes a compelling argument that the discipline of history has changed over time, and that part of that change is related to the pressing need in France to unpack events for which there was little temporal distance (i.e. WWII, the Holocaust, and the war in Algeria). He rightly questions what the proper realm of historical distance is when we have journalists, sociologists, and anthropologists on the case for more contemporary developments. That is all fine, but his argument that history is now part of politics is contradicted by most of what he writes about nationalist history before WWII. What I get from his piece is that he is struggling to contend with the denaturalization of conceptual frameworks and assumptions that he is more comfortable with. I can empathize with his position and how he might feel, but I don’t have much sympathy with that line of argument.

To all our non-English speaking readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator. Just copy and paste.

Gabriel Reich offers a sharp, insightful look into the significance of historical consciousness in debates over sites of memory and raises important questions – implications – for my own argumentation. Nora’s “general politicisation of history” should be understood in its referential context of Nora’s metaphorical rivalry between “memory” (the practice of remembrance and heritage fashioning) and “history” (the intellectual activity of reconstructing the past as representations). For him, the current acceleration of global change has led individuals and groups alike to a deep sense of instability and historical sensibility unprecedented in human history. This acceleration has resulted in a pressing need to (re)connect with the past – real or invented – as a way to (re)orient their life. Monuments as “anachronistic medium”, as Reich puts it, inevitably become in this context contested realms of memory – statues representing for some individuals their own heritage, their own roots that (morally) need to be defended for safeguarding “their own sense of self” vs. statues that symbolize a racist, white supremacist past that we should object and negate in modern society. General politicisation of history occurs when identity politics takes over critical distance and temporalised moral values, hence my argument over the need for competencies of historical consciousness.

Rüsen’s typology of historical consciousness, as Reich rightly hints, can help us delineate a progression model for structural change in our dealing with the complexity of history and memory. While Rüsen meant to offer a typology that encompasses the entire field of empirical manifestations of historical thinking, the articulation of distinctive dimensions into competencies (see my figure) can provide useful, distinctive abilities to carry out the procedures for thinking historically about the past and, by extension, the present and envisioned future. I do not know enough about U.S. Confederate monuments to characterize the current debate as one of “exemplary stance”. But I believe that both sides (or all sides) would gain from a progression to more “genetical” type of historical consciousness that cultivates the capacity to “digest complexity” – both human and societal. Memory and identity politics thrive on tribalism and cognitive simplification. Yet, societies and their pasts are highly complex and multifaceted, and need to be analyzed and recognized as such. Representations of the past as well as individual and collective courses of action might better be informed by this genetic sense of historical complexity. Any attempt to delineate this intellectual complexity of historical consciousness runs the risk of cognitive and normative simplifications but the following model intends to offer a preliminary matrix as a starting point for further discussion (and transposition) on how individuals and groups position themselves and engage in issues of commemoration.

Internalization of a pre-given sense of life shaped by the permanence of the group to which one belongs. Past, present, and future are bound in a sense of eternity.

Specific concepts and cases offer general rules and principles for orienting our present-day life. The dimensions of time are recognized and connected through general rules for guiding our actions.

Individuals feel no obligation to predecessors but establish value-laden principles to define their own course of actions. Past, present, and future are distinct and only connected through a negative sense of rupture.

Continuity and change are relational and essential to life orientation. They give history its sense and purpose. Temporalisation is a decisive instrument for the validity of historical claims and moral values. Dimensions of time are connected as a path for future possibilities.

To all our non-English speaking readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator. Just copy and paste.

Thank you, this indeed gets interesting. Just a few comments:

First of all, I strongly support the initiative to analyse monuments as an expression of and factor for historical consciousness. Indeed, we need both a) to analyse them as experts by using our repertoire of historiographic methods and concepts in order to stimulate and support informed public discussion about whether a particular monument is still desirable (or at least acceptable) or whether it needs to be changed (and how) or even removed, and b) to develop people’s competences to address these issues themselves, i.e. to reflect on the nature, meaning and message of a monument both at the time of its construction and today (e.g. through preservation, maintenance, alteration, commenting or removal).

For this reason, I greatly appreciate Stéphane’s proposal for a competency model, especially the table version from the commentary above. This does not mean that I fully support the concrete model, but it has enriched the debate. Three comments on this:

(1) I doubt that competence as such can be “traditional”, “exemplary”, “genetic”, “critical” or “genetic”. These patterns, both as I understand Rüsen and for myself, characterize the logic of narratives. I would therefore rather read the table as “the competence to query in the traditional mode” … “the competence to narrate in critical mode” etc.

(2) This again raises the question of whether the four patterns actually constitute a distinction of competence niveaus. While I agree that the genetic mode of narrating history is the historically most recent, complex and suitable for explaining changes, I doubt – this time against Rüsen (cf. Körber 2016) – that the typology can describe competence levels.[1]

The competence progression would need to be defined transversally: From (a) a basic level of non-distinctive (and thus unconsciously confusing) forms and patterns, via (b) the ability to perform all these forms of operations in the various patterns of Stéphane’s table (which would this describe a fully developed intermediate level), to (c) an elaborated level of (additional) ability to think about the nature of these disctions, etc.

For this, the model is very useful, full of ideas. It can help to think about what it takes to describe monuments neither as “the past” nor as “simply old”, but to identify and “read” them as narratives (or narrative abbreviations) from a certain time, whose current treatment adds new narrative layers to them, so that their existence (or absence), form, and treatment of them can always be seen and evaluated as contemporary statements about the respective past. To recognize this and to deal with it in a socially responsible way requires these competences.

As far as Gabriel Reich’s commentary is concerned, I only ask whether his characterization of an attitude to the confederation monuments can really be addressed with Rüsen as “exemplary”, since this mode is not concerned with the maintenance and support of a conventional identity, but with the derivation of a supertemporal rule. I would refer to the example as “traditional”. An “exemplary” attitude towards retention would be more likely to be: “At all times, monuments of one’s own heroes have helped the losers of war to hold on to their cause. Then that must be possible for us too.” Or something along that line.

References

[1] Andreas Körber, “Sinnbildungstypen als Graduierungen? Versuch einer Klärung am Beispiel der Historischen Fragekompetenz,” in Historisches Denken jetzt und in der Zukunft. Wege zu einem theoretisch fundierten und evidenzbasierten Umgang mit Geschichte. Festschrift für Waltraud Schreiber zum 60. Geburtstag, ed. Katja Lehmann, Michael Werner and Stefanie Zabold (Berlin/Münster: LIT-Verlag, 2016), 27-41.

Please see an extended version of this comment in Andreas Körber’s personal weblog:

https://historischdenkenlernen.userblogs.uni-hamburg.de/index.php/2018/10/15/a-new-competency-model-on-monuments-using-ruesens-four-types-by-stephane-levesque-and-a-comment/

To all our non-English speaking readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator. Just copy and paste.

Andreas Körber’s analysis of my supplemented matrix of historical consciousness (as detailed on his blog post [see the link in the footnotes]) offers a valuable and, to my own excitement, possibly more robust and empirically sound research-based model that likely represents learners’ own inconsistent use (and progression) of competence to query, thinking historically, orient, and narrate.[1]

It is completely understandable that learners (no less than adults) make sense of the past (or in this case monuments) as an uninformed mixing of different levels and forms of competence. As Denis Shemilt and Peter Lee have argued, learners’ historical ideas do not develop in a linear manner; they are decoupled. Students can ask questions at a critical form/level but reason though a traditional competence of historical thinking.

Körber offers an additional (3D) dimension to my model that highlights this sense of contingency and decoupling. At the most basic level, learners are unable to realize the different modes and set of competences. At an intermediate level, they (A) understand the nature of historical thinking and (B) realize their own inconsistencies in how they engage with and think about monuments as sites of memory. They may also aim to (C) progress in the sophistication and development of their own ideas about monuments and as narratives about them. At a highest level, learners are conscious of their own limitations as well as the ones of typologies themselves. They are “in full command” of their historical reflection and consciousness, able to suggest their own amended versions for orientation and live purpose.

Körber suggests that my matrix is most likely situated at the intermediate level, where both learners and educators are in a position to map out the range of ideas that people hold with regard to the past or monuments. Shemilt and Lee warn about the danger of turning such normative progression model into a prescribed ladder-like system where learners should gradually move from one level to another. There is no clear indication or instruction suggesting that learners will cognitively progress in lineal terms. Development in one competence does not automatically generate progress in another. On the other hand, such model would need to be adapted (and redefined) for didactical purposes. Both Körber’s complex 3D model and my own suffer from poor empirical testing and educational validation. A this point, I do not see how we could pedagogically apply this 3D matrix in the evaluation of learners’ prior knowledge of history and, subsequently in the development of successful pedagogical lessons for progression in students’ complexity of historical ideas. To be usable, models of progressions should not only map out learners’ ideas, they must also inform teaching and assessment. This is, in my view, the greatest challenge…

References

https://historischdenkenlernen.userblogs.uni-hamburg.de/index.php/2018/10/15/a-new-competency-model-on-monuments-using-ruesens-four-types-by-stephane-levesque-and-a-comment (last accessed 15 October 2018).

To all our non-English speaking readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator. Just copy and paste.

Stephane’s summation of Nora’s anxious project is accurate. I agree that humans seek out ideas that connect them to something larger and more meaningful. Rüsen also takes that need seriously, and offers a theory of historical consciousness that he applies ecumenically to all, rather than just to professional historians. As Stephane points out, that theory is hierarchical as well, with a trajectory towards a well-informed, epistemologically sophisticated and cosmopolitan perspective on the past. In an era marked by anger, particularly at “others,” I agree that using the study of history to help students develop towards that kind of historical consciousness is laudable. More specifically, I believe that such a goal is useful towards a specific political end, engendering a citizenry that practices empathy, is hesitant to accept simple causal arguments, looks for nuance and strives for tolerance.

Nora and Rusen both argue for approaching the past from a distance that removes history from political rhetoric and expediency to contemporary identity projects. There are good reasons to do so, however, Rüsen’s description of a person who has achieved genetic historical consciousness (which assumes great distance from the pull of memory/identity projects) is itself a statement of political preference. Rüsen does not mention politics or affect by name, but his vision of genetic historical consciousness values tolerance, intellectual distance, even temperedness. Mary Beard is a scholar who engages in public discourse and who displays the intellectual and affective traits of genetic historical consciousness. She has also been ruthlessly attacked for her consulting work on a cartoon about Roman era Britain that includes an African character, a character whose existence is supported by written records from the time. My point is that distance from politics when dealing with all but the most academic of historical questions is not really achievable.

Like Andreas, I also find Stephane’s table a useful tool for thinking about ends and means in history instruction and worry about it being used as a set of descriptors for judging student achievement. For secondary education, genetic historical consciousness is a useful point of reference. However, it seems unrealistic to expect more than a few students to achieve it. Moreover, it is not necessarily a superior stance to take when we consider history education as preparation for democratic citizenship.

Let us take Andreas’s characterization of a person who is considering Confederate monuments from a genetic standpoint. I will paraphrase a little “At all times, monuments of [Confederate] heroes have helped the losers of the [Civil War] to hold on to their cause. Then that must be possible for us too.” The civic manifestation of that attitude is to call for additional monuments to be erected to, say African Americans who fought for freedom, and/or to have signage that contextualizes all those figures historically – rather than just repeating the myths that their forms are “narrative abbreviations” for. In the reality of democratic politics however, that stance achieves little in terms of affecting the present or future because there is a strong reaction to any suggestion of change. In other words, the praxis of politics often requires a rhetorical register that is quite different from the genetic one.

To all our non-English speaking readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator. Just copy and paste.

There is really a lively discussion emerging here.

As for Gabriel Reich‘s paraphrasing of my example, I sense a misreading. My phrasing was not meant to exemplify the genetic, but rather the exemplaric mode / pattern of thinking. Stéphane Lévesque‘s table might be of use for clarification.

Let’s consider different persons thinking about civil war monuments and their history:

A person asking for the origin of upholding a certain memory and interesting in mainly “carrying it further” would argue in traditional logic (in German language and terminology we can distinguish between “traditionell” signifying a handed-down practice, and “traditional” signifying the logic of such orientation).

If a person asks for good examples of commemorating, looking at the development of monument design with a clear interest in identifying those forms of monuments which best signify individual’s and group’s heroism and dignity or which best express mouring, this would be exemplaric. Such exemplaric search for a rule about how to best commemorate will inform the questions the person asks (inquiry), her/his methods (historical thinking), orientation and subsequently the narrative she/he provides, e.g. in a book about “The development of civil war commemorations”. The basic logic of such approach would be to accept differences and certain developments, but in general to discern a time-spanning rule. Each monument is considered an example for a certain type of commemoration, which it can represent more or less good, so that one can learn from them.

If the person, however, looks at the same history of civil war commemoration worrying whether certain forms of commemorating are not only more or less good examples (for a certain type or in general), but also whether they are representing a certain “Zeitgeist”, so that it is quite impossible to just learn from them in exemplaric mode. Instead, for this person, the development of civil war memory needs to be researched under the question, what parts, which modes, are still acceptable, and which are kind of “outdated”. This, now, can take two flavours:

If the person asks for a commemoration and memorials which “fit our time” as older monuments fitted theirs, researches the development under the question of how each “Zeitgeist” figurates in the memorials, and uses this for orientating her own ideas of what might be appropriate commemoration today, this would also be a kind of exemplaric meaning making (and thus yield a respective narrative).

If, however, the interest of the person lies in changing and improving commemoration, they might look into the history of civil war commemoration asking for what new initiatives moved commemorating forward. They might, e.g. ask for how and when new groups were included (e.g. civilians, women, etc.), looking for hints for further improvement. This would be a truly genetic approach, informing both the inquiring, the research, the orientation (e.g. in campaining for specific forms of monuments), and possible narratives.

Members of society should be able to recognize not only different political positions and stances, but also the different narrative logics in the debate.

Additions:

There is a kind of continuation to this comment on my blog under the following link:

https://historischdenkenlernen.userblogs.uni-hamburg.de/index.php/2018/10/16/analyzing-monuments-using-crosstabulations-of-historical-thinking-competencies-and-types-of-narrating/ (last accessed 16 October 2018).

Here, I just want to refer to another crosstabulation of historical thinking competencies and Rüsen’s types of sensemaking (in German) by Wolfgang Hasberg.[1] My critique of it is in Körber 2016.[2] I also provided an own table there, including the different niveaus, but restricted to “Fragekompetenz” (similar to Stéphane’s “inquiry competence”, and using the enhanced version of Rüsen’s typology from Körber 2013 (English: Körber 2015, p. 15).[3]

I am deliberating on translating it some time.

References

[1] Wolfgang Hasberg, “Analytische Wege zu besserem Geschichtsunterricht. Historisches Denken im Handlungszusammenhang Geschichtsunterricht,” in: Was heißt guter Geschichtsunterricht? Perspektiven im Vergleich, ed. Johannes Meyer-Hamme, Holger Thünemann and Meik Zülsdorf-Kersting (Schwalbach/Ts.: Wochenschau, 2012), 137–160. Here: 140.

[2] Andreas Körber, “Sinnbildungstypen als Graduierungen? Versuch einer Klärung am Beispiel der Historischen Fragekompetenz,” in Historisches Denken jetzt und in der Zukunft. Wege zu einem theoretisch fundierten und evidenzbasierten Umgang mit Geschichte. Festschrift für Waltraud Schreiber zum 60. Geburtstag, ed. Katja Lehmann, Michael Werner and Stefanie Zabold (Berlin/Münster: LIT-Verlag, 2016), 27-41.

[3] Andreas Körber, “Historische Sinnbildungstypen. Weitere Differenzierung,” 2013. http://www.pedocs.de/volltexte/2013/7264/ (last accessed 16 October 2018). Andreas Körber, “Historical consciousness, historical competencies – and beyond? Some conceptual development within German history didactics,” 2015. https://www.pedocs.de/volltexte/2015/10811/pdf/Koerber_2015_Development_German_History_Didactics.pdf (last accessed 16 October 2018).

To all our non-English speaking readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator. Just copy and paste.

Thanks to Stéphane, Gabe, and Andreas for contributing to this stimulating discussion. I very much appreciate Stéphane’s preliminary matrix for thinking about how individuals and groups position themselves and engage in issues of commemoration, and for Andreas’ suggestions for improving this matrix. I look forward to seeing this matrix further developed, but like Gabriel I have concerns about this being used as a model for assessing student competence in historical consciousness.

Although much more simplistic than what Stéphane has proposed, in a December 2017 post on Active History I used Seixas’ model of historical thinking to develop a framework of questions that can be utilized by teachers, students, and the general public to think historically about commemoration controversies.[1]

The HT concepts are powerful tools for getting at the important inquiry questions that invite people to approach monuments and commemorations as constructed narratives, and think historically about how best to respond in the present. In my estimation, these questions get at the heart of the key issues about how to think historically about these commemoration controversies, and in some ways address many of the issues in the inquiry, historical thinking, orientation, and narrative competencies.

References

[1] http://activehistory.ca/2017/12/thinking-historically-about-canadian-commemoration-controversies/ (last accessed 17 October 2018).

To all our non-English speaking readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator. Just copy and paste.

I want to thank Lindsay Gibson for his insightful response to my recent Public History Weekly article as an additional contribution to debates over commemoration, using Canada as a context for his analysis. The role and value of historical thinking (HT) as an intellectual tool for “getting at the important inquiry questions that invite people to approach monuments and commemorations as constructed narratives” is uncontested. Lindsay demonstrates how students – no less than adults – can strategically use HT key concepts and related set of questions in dealing with contested and emotional debates over contested monuments such as John A. Macdonald. Having written extensively on HT, I strongly support the consideration of such a pedagogical approach to public debates.

But in my view, the HT framework presented by Lindsay is incomplete and unsatisfactory because it transcends learners’ own values, beliefs and perspectives about history (and narratives) and thus fails to recognize and contextualize HT in the sociocultural and ontological contexts in which historical thinking realizes its function of critical analysis and judgment – what I refer to in my article as “historical culture”. As a theory, historical consciousness offers, in my view, a more robust model (and body of knowledge) to commemoration because it situates the debates and people’s own positionality within the context of an internally-mediated cultural environment that orients – determine (?) – their own identity, thinking, and judgments. As such, I have proposed to include HT as one of the competencies of historical consciousness (see my Figure) but not the only one. Indeed, to make sense of commemoration debates, and perhaps more importantly how individuals position themselves within the debates, it is necessary to consider their inquiry, orientation, and narrative competencies. Individuals approach commemoration with different valid questions that lead them to distinctive inquiries and related narrative representations as I expressed in my applied Table on Confederate monuments. There are indeed many roads to Roma and some may even decide to head to Paris!

In my article, I have showed, for example, how individuals position themselves and develop competence to deal with commemoration within traditional, exemplary, critical, and genetic modes of investigation and narrative (see my Initial Table). The questions of HT devised by Lindsay provide us with very useful tools to engage with monuments as narrative abbreviations, but they do not account for how individuals will use them and for what purpose (preserve, remove, change, occlude, etc.) Individuals and groups can respond differently to controversies and to their use of key concepts (appropriate, resist, revise, devise, etc.). We know that language, identities, and attachment to the past (or to certain communities of memory) strongly influence the production and appropriate of knowledge. As Andreas Körber rightly contends, models of historical consciousness, as the one I offered, can find their value in characterizing the logic underlying historical understanding and uses of the past. There are different positions and solutions possible for each narrative framework. The value of the differentiation of types of meaning making and narration is rather analytical than prescriptive.

Indeed, models of historical consciousness may lead educators to naively use them as assessment tools for evaluating progression in historical learning, as Lindsay suggests. Such is not my goal. In fact, I have indicated that it is possible to develop progression both within and across types of historical consciousness (so that the genetic type is not necessarily the preferred one). At a most advanced level, for instance, individuals can (1) recognize the logics behind specific political stances and narrative orientations, (2) generate more complex polythetic narrative representations of the past and monuments, and (3) understand the contingency of historical thinking as a time and contextually situated paradigm for making sense of the debates. They can even (4) propose different models and related set of key concepts and competencies that are equally valid for making sense of memorials (that is, being “in full command” of their historical consciousness, able to reflection on limits on modes and sets of representation and suggest alternative modes of analysis and representations).

To all our non-English speaking readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator. Just copy and paste.

Following the engaging discussion surrounding my article and related analytical matrix of distinctive abilities to carry out the procedures for thinking historically about monuments and sites of memory, I have transposed in a table the various comments (thanks to Andreas Körber and Gabriel Reich) so as to get a sense of its practical application. Below is one example of how we could map out people’s ideas and engagement with Confederate monuments along the lines of traditional, exemplary, critical and genetic stances.

The related question of “progression” in people’s ideas (from simple and naive to more complex and multidimensional) is still subject to further discussion and analysis. As Körber rightly claims, the development of competencies to deal with debates over monuments should not be viewed exclusively in horizontal terms from “traditional” to “genetic.” It might also be conceived transversally from “basic” (being unconscious of the distinctive modes and set of representations) to “elaborated” (“in full command” of our historical consciousness, able to reflection on our limits and suggest alternative modes of analysis and representations). As a cautionary note, any political project to change the present U.S. state of affairs or alter the future cannot be held accountable to a particular stance in the circumstances.

(keep the monuments)

(explain the monuments)

(replace the monuments)

(change commemoration)

and

Narrative

To all our non-English speaking readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator. Just copy and paste.

Thanks a lot, Lindsay. I don’t think that Stéphane’s matrix using Rüsen’s types of narrating and your application of Peter Seixas’ Big Six concepts of Historical Thinking do mutually exclude each other, when it comes to thinking about narratives. I fact, I do think they complement each other. And each of them can be applied on different levels.[1]

But there is more to reflecting about narratives – and especially on how to relate to them. Memorials are narratives, or “narrative abbreviations” (Rüsen), pointing to them standing for a specific narrative, i.e. a specific relation between a past (under memory), the present (of the authors and erectors of the monument as well as the intended public), and with regard to a specific future, constructed only partly in verbal narrative form, but also with non-verbal and sequentially narrative elements.

Memorials are more than only proto-narratives. Their (often) prominent (albeit also often overlooked) positioning, their (proto-)narrative structure and their own quality for lasting a long time (cf. “monumentum exegi aere perennius”), they do not only constitute a narrative relation from one temporal and social position towards the past and the future, but also are meant to prolong the sense they make and to impose it on later generations. Monuments are about obligating their audience, the spectators with a certain narrative and interpretation. That qualifies them as parts of what we call “politics of history”, not only of commemoration, and what makes them political.

It therefore is paramount to read monuments as narratives, and not only in the de-constructive sense of “what did those erectors make of that past back then”, but also in the re-constructive sense of “in how far or how does this narrative fit into my/our relation to that past”. Standing before a monument and thinking about monuments, we all need to (and in fact do) think in a combination of understanding the others’ and deliberating our own narrative meaning-making. Therefore we must learn to read them as narratives.

Monuments often take on the form of addressing people. Sometimes they address the spectator, reminding them of some kind of obligation to commemorate. But who is talking to whom? If the senate of Hamburg talks to that to the Hamburg citizens of 1930-1932, can/will we accept that (a) the Hamburg Senate of today still admonishes us like that, and (b) that we Hamburg citizens of today are still addressed in the same way? In other cases, (inscriptions in) memorials might explicitly address the commemorated themselves, as e.g. in the confederate monument in Yanceyville, N.C., whose plaque reads “To the Sons of Caswell County who served in the War of 1861-1865 in answer to the Call of their County”, and continues in a “We-Voice”, signed by the Caswell Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy”. So far so conventional. This might be rather unproblematic, since speaker-position and addressees are clearly marked. One might leave the monument even if one disagreed, not having to align with its narrative. Only if the presence of such commemorating in itself is inacceptable, action is immediately called for.

But there are other monuments which seem to talk from a neutral position, which in fact is that of the erectors, but by not being qualified, includes the spectator into the speaker position. The example I have ready at hand, is not from the US and not about war heroes, but again from Hamburg, this time from Neuengamme concentration camp memorial. In 1965, an “international monument” stele was erected there, together with a whole series of country-specific memorial plates. The inscription on the monument reads “Your suffering, your fighting and your death shall not be in vain” (my translation).

This now clearly is interesting in at least two respects: (1) it ascribes not only suffering and death, but also fighting to those commemorated and thereby possibly does not refer to those inmates who never had a chance or did not “fight”, who were pure victims, and (2) it speaks from a neutral voice which is not marked in time and social, political or event-related position. Whoever mourns at that place possibly silently co-signs the statement.

Consider an equal honoring of confederate generals in, say NC: “Your fighting shall not have been in vain.” I would spark much more controversy and concerns – and rightly so.

In order to make up our minds on monuments we have “inherited” not only in political terms, we need to reflect their specific narrative message in a spectrum of time-relations. And we need to differentiate our terminology and enable our students to master a set of concepts related. We need, e.g., to distinguish honoring commemoration from reminding and admonishing. In Germany we have (not easily) developed the notion of “Mahnmal”, admonishing, to be distinguished from a mere “Denkmal”. But even this distinction is insufficient. A Mahnmal (in fact the literal translation to “monument”, from Latin “admonere”) may admonish to remember our own suffering inflicted on us by ourselves, some tragic or by others, but also may admonish to not forget what we inflicted on others. This is the specific form “negative memory” of German memorial culture.

Therefore, there’s a lot more to be reflected in commemorating:

* Who “talks”? Who authors the narrative – and is what capacity (e.g. in lieu of “the people”, of a certain group, …)?

* Whom does the monument explicitly address?

* What is the relation of explicit addressees and factual spectators?

* In how far is the message the same for us today as it was envisioned back then – and possibly realized? is it the same for all of us?

* What kind of message is perceived?

References

[1] ] Also in https://historischdenkenlernen.userblogs.uni-hamburg.de/index.php/2018/10/16/analyzing-monuments-using-crosstabulations-of-historical-thinking-competencies-and-types-of-narrating/ (last accessed 20 October 2018).