Abstract: Whatever the epistemological status of public history or of history didactics might be, public interest in the development of history education cannot be denied. In order to further contribute to the debate about the relationship between history didactics, public history, and historical culture, I would like to identify historical culture as the common denominator of the other two.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-11540.

Languages: ελληνικά, English, Deutsch

Δύσκολο να αρνηθεί κανείς το δημόσιο ενδιαφέρον που υπάρχει στην κοινωνία για τις εξελίξεις στην ιστορική εκπαίδευση, ανεξάρτητα την επιστημολογική διάσταση είτε της δημόσιας ιστορίας είτε της διδακτικής της ιστορίας. Επιδιώκοντας να συμβάλω στη συζήτηση αναφορικά με τη σχέση διδακτικής της ιστορίας, δημόσιας ιστορίας και ιστορικής κουλτούρας, θα ήθελα να προτείνω ότι η ιστορική κουλτούρα θα μπορούσε να είναι ο κοινός παρονομαστής των άλλων δύο.[1]

Ιστορία, Δημόσια Ιστορία, Ιστορική Κουλτούρα

Όταν το ηλεκτρονικό περιοδικό Historein δημοσιεύτηκε το 2003 με τον τίτλο “δημόσιες ιστορίες”[2] στόχος του ήταν να φέρει στο προσκήνιο τη συζήτηση για τη δεύτερη ζωή του παρελθόντος, την αναβίωση του παρελθόντος στο παρόν, τη δημόσια και όχι κατ’ ανάγκη την επιστημονική διάσταση του παρελθόντος. Όπως ανέφεραν οι Λιάκος και Μπιλάλης,

“διαφορετικά παρελθόντα επανενεργοποιούνται υπό διαφορετικές συνθήκες … και κανείς δεν ξέρει πότε, υπό ποιους όρους […] θα ξεκινήσουν πόλεμοι για το παρελθόν [για άλλη μια φορά]”.[3]

Αυτός είναι και ο λόγος για τον οποίο η εμπειρία του παρελθόντος στο παρόν και οι τρόποι με τους οποίους το παρελθόν αναπαρίσταται στο παρόν αποτελούν σήμερα ένα επιπλέον αντικείμενο έρευνας για τον ιστορικό.

Στο παραπάνω πλαίσιο οι Λιάκος και Μπιλάλης αναφέρονται στον Ankersmit[4] “για να μάθουμε ιστορία πρέπει να δώσουμε προτεραιότητα στην εμπειρία της ιστορίας”. Ο Goschler στο σχόλιό του στην παρέμβαση του Demantowsky στο Public History Weekly, τονίζει την ακαδημαική προέλευση της δημόσιας ιστορίας και ότι αποτελεί ένα δημοφιλές προϊόν ιστοριογραφίας που προορίζεται για μη έμπειρα ακροατήρια, όπως επίσης και η ιστορία ‘από τα κάτω’· τα παραπάνω θα μπορούσαν να συνιστούν εκδημοκρατισμό του επαγγέλματος του ιστορικού καθώς το μονοπώλιο της ερμηνείας του παρεθόντος φαίνεται να έχει καταργηθεί.[5]

Ενώ οι Λιάκος και ο Μπιλάλης επικεντρώνονται στην ιστορία στο δημόσιο χώρο και φαίνονται να τη θεωρούν πολιτισμικό προϊόν προς ανάλυση από τον ιστορικό, ο Goschler ασχολείται με την ιστορία που παράγεται από το ίδιο το ‘κοινό’ ή για το κοινό. Ο Αθανασιάδης με αφορμή την έρευνά του για τον ‘πόλεμο της ιστορίας’ που ξέσπασε στην Ελλάδα το 2006 για σχολικό βιβλίο ιστορίας του δημοτικού σχολείου, κάνει διάκριση ανάμεσα στην ιστορία που παράγεται για το ευρύ κοινό από τους ακαδημαϊκούς, την ιστορία από τα ‘κάτω’, όπως είναι και η προφορική ιστορία, ή ό,τι κάνει ο ίδιος στο βιβλίο του, τους ‘πολέμους για την ιστορία’ ως πεδίο εθνογραφικής και ιστορικής έρευνας.[6]

Διδακτική της Ιστορίας, Δημόσια Ιστορία, Ιστορική Κουλτούρα

Διαβάζοντας για την εστίαση πλέον των ιστορικών στην ιστορική κουλτούρα και το γεγονός ότι τείνει να αντικαταστήσει τη θεωρία της ιστορίας,[7] σκέφτηκα ότι ειδικά η διδακτική της ιστορίας είχε πάντα μια πολύ στενή σχέση με τον ιστορική κουλτούρα, αφού κατά τον Jacobi είναι απαραίτητη η ‘τροποποίηση’ των επιστημονικών όρων προκειμένου [να διδάξει] κάποιος μη έμπειρους αναγνώστες.[8] Όπως θα έλεγε και η Κάββουρα, φαίνεται ότι στο σχολείο έχουμε την επίδραση της σχολικής ή της παιδαγωγικής κουλτούρας στο επιστημονικό εκείνο περιεχόμενο που έχει επιλεγεί για να διδαχτεί.[9] Πολύ πριν από τη “Νέα Ιστορία” στην ιστορική εκπαίδευση ενώ δε γινόταν λόγος για πηγές, εικονικές ή άλλες, οι εκπαιδευτικοί παρόλα αυτά ενθαρρύνονταν να χρησιμοποιούν ‘εποπτικά’ μέσα στην τάξη. Αυτό δε σημαίνει ότι εκείνη την εποχή υπήρχε η προσδοκία ν’ αναπτύξουν οι μαθητές ‘εγγραματισμούς’ διαφορετικών τύπων· Εκείνα τα χρόνια, οι μαθητές ήταν παθητικοί καταναλωτές έτοιμου ιστορικού περιεχομένου, ενώ οι χάρτες ή τα άλλα εποπτικά μέσα υποτίθεται ότι διευκόλυναν τη δυνατότητα τους για “[επιφανειακή] αναπαραγωγή”[10] του παραπάνω περιεχομένου. Από το μέτωπο των μουσείων, η αναγνώριση της εκπαιδευτικής αξίας του υλικού πολιτισμού είχε ήδη γίνει στο Μεσαίωνα και από το Θωμά τον Ακινάτη που είχε τονίσει τη συμβολή των αισθήσεων στη μάθηση. Η Hooper-Greenhill πάλι δηλώνει ότι “η μάθηση είναι μια διαδικασία ενεργού συμμετοχής στην εμπειρία”.[11]

Η άποψή μου είναι ότι η ιστορική γνώση στο σχολείο ήταν πάντα επιστημονική γνώση τροποποιημένη προκειμένου ν’ ανταποκριθεί στις ανάγκες των μαθητών ή στην κρατική απαίτηση για την ανάπτυξη πολιτειότητας και πατριωτισμού κυρίως μέσα από το συγκεκριμένο μάθημα. Κατ’ αυτήν την έννοια, η διδασκαλία της ιστορίας ήταν πάντοτε μία “δημόσια” διαδικασία. “Δημόσια” με την έννοια ότι αποτελούσε εκλαΐκευση της ιστορικής γνώσης μια και αφορούσε μαθητές διαφορετικών ηλικιών.[12] Αυτά όσον αφορά την παραδοσιακή ιστορική εκπαίδευση.

Τι γίνεται τώρα με τη “Νέα Ιστορία” ή το κονστρουκτιβιστικό παράδειγμα στην ιστορική εκπαίδευση; Ο Chris Husbands στο κλασικό βιβλίο “Τι είναι η διδασκαλία της ιστορίας;” ενθαρρύνει τους δασκάλους να χρησιμοποιούν μη τυπικά περιβάλλοντα εκπαίδευσης όπως τα μουσεία, εξηγώντας ότι “η οικοδόμηση ερμηνειών για το παρελθόν εξαρτάται από τη σύνδεση αυτού που βλέπουμε με αυτό που ήδη σκεφτόμαστε για το παρελθόν, από τις ιδέες τις οποίες εμείς ή τα παιδιά μας φέρνουμε στο μουσείο”. Κατ’ αυτόν τον τρόπο εάν δοθεί στους μαθητές στα μουσεία επαρκής χρόνος να εκφραστούν, είναι πιθανόν να “αναδομήσουν τις “μικροθεωρίες” τους και να ξεπεράσουν τις παρανοήσεις τους”.[13] Οι Cooper κ.ά. στο βιβλίο τους “Οικοδομώντας την Ιστορική [Κατανόηση], 11-19” και χρησιμοποιώντας στοιχεία υλικού πολιτισμού, εφημερίδες, ή άλλες μη ‘επίσημες’ πηγές, ενθαρρύνουν τους μαθητές τους να ενεργήσουν ως ‘ντετέκτιβ του παρελθόντος’ και να κατασκευάσουν τα δικά τους ντοκιμαντέρ και ιστορικούς ιστοτόπους. Όλα τα παραπάνω, παρουσιάζονται ως μελέτες περιπτώσεων για ερευνητικές εργασίες στο σχολείο και στο πλαίσιο του κονστρουκτιβισμού.[14]

Περισσότερο από ποτέ, η ιστορία στο σχολείο διαμεσολαβείται από την ιστορική κουλτούρα, τον υλικό πολιτισμό, τα ψηφιακά μέσα, το δράμα, πρακτικές δηλαδή από μη τυπικά εκπαιδευτικά περιβάλλοντα μεταφέρονται στο σχολείο. Ακόμα και τα βιβλία που συνιστούν ένα παραδοσιακό εκπαιδευτικό μέσο έχουν αλλάξει:

“[τα βιβλία της ιστορίας σήμερα] έχουν νέα δομή […] ενώ η εικονογράφηση διακόπτει την ενότητα του γραπτού κειμένου δημιουργώντας νέο πολυτροπικό κείμενο και περιεχόμενο […] ένα είδος κειμένου που δε δίνει απαντήσεις αλλά υποστηρίζει τη μάθηση σε περιβάλλον εργαστηρίου”.[15]

Τέλος, από το ψηφιακό μέτωπο ο Chapman (2016) καταλήγει στο συμπέρασμα ότι σε ορισμένα βιντεοπαιχνίδια είναι δυνατό οι παίκτες όχι μόνο να προσομοιώσουν το παρελθόν αλλά και το λόγο για το παρελθόν. Ονομάζει αυτά τα παιχνίδια “εννοιολογικής” προσομοίωσης σε αντίθεση με τα παιχνίδια της “ρεαλιστικής” προσομοίωσης, τα οποία και θεωρούνται ότι έχουν υιοθετήσει μια παραδοσιακή επιστημολογία. Τέλος, μερικά βιντεοπαιχνίδια παρέχουν στους παίκτες ένα σύστημα μέσα στο οποίο μπορούν να αναπτύξουν ιστορικά επιχειρήματα.[16]

Συμπέρασμα

Τόσο η επαγγελματική ιστορία όσο και η διδακτική της ιστορίας είναι “δημόσιες”: ενώ οι ιστορικοί ήταν δημόσια πρόσωπα από τον 19ο αιώνα,[17] η διδακτική της ιστορίας ερευνά τους τρόπους με τους οποίους μπορεί να γίνει πιο αποτελεσματική η διδασκαλία για το παρελθόν. Άρα τόσο η ιστοριογραφία, όσο και η διδακτική της ιστορίας ασχολούνται εξίσου με τη ‘διάχυση’ της ιστορικής γνώσης. Η ιστορική κουλτούρα φαίνεται τελικά να διαπερνάει τη διδακτική της ιστορίας ως διαφορετικά περιβάλλοντα μάθησης, τη δημόσια ιστορία ως οι διαφορετικοί τρόποι με τους οποίους αναπαρίσταται το παρελθόν στο παρόν, αλλά και την ακαδημαική ιστορία ως πολιτισμικό προιόν που θα αναλυθεί από τους ιστορικούς.

_____________________

Συνιστώμενη Βιβλιογραφία

- De Groot, Jerome. Consuming History: Historians and Heritage in Contemporary Popular Culture. London: Routledge, 2008.

- Chapman, Adam. Digital Games as History: How Videogames Represent the Past and Offer Access to Historical Practice. London: Routledge, 2016.

Δικτυακές Πηγές

- http://blog.europeana.eu/ (τελευταία πρόσβαση 15.02.2018).

- Ομάδες Προφορικής Ιστορίας στην Αθήνα: http://oralhistorygroups.gr/ (τελευταία πρόσβαση 15.02.2018).

_____________________

[1]Έναυσμα για την παρακάτω παρέμβαση ήταν πρώτον τα δύο σεμινάρια που διοργάνωσε το περιοδικό Historein στην Αθήνα υπό τον τίτλο “Θεωρητικοποιώντας την Ιστορική Κουλτούρα”, (Μάιος και Δεκέμβριος 2017) και τουλάχιστον δύο παρεμβάσεις στο Public History Weekly μαζί και με τα σχόλια συναδέλφων που αποσκοπούσαν στον ορισμό της δημόσιας ιστορίας (Marko Demantowsky, “‘Public Histor’- Sublation of a German Debate?” σε: Public History Weekly 3, no. 2 (2015), DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2015-3292 (τελευταία πρόσβαση 15.02.2018)). ή της σχέσης της με τη διδακτική της ιστορίας (David Dean & Joanna Wojdon, “Public History and History Didactics – A Conversation” σε: Public History Weekly 5, no. 9 (2017), DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-8656 (τελευταία πρόσβαση 15.02.2018)). Δεύτερον οι πρόσφατες αναφορές στον ελληνικό τύπο (Μάρνυ Παπαματθαίου, “Νέες αλχημείες Γαβρόγλου στο εξεταστικό”, Τα Νέα, 23 Νοεμβρίου 2017, http://www.tanea.gr/news/greece/article/5489576/nees-alxhmeies-gabrogloy-sto-eksetastiko (τελευταία πρόσβαση 15.02.2018)) και Ελπίδα Οικονομίδη, “Μαζεύουν την κατάργηση της ιστορίας στην Δ’ Δημοτικού”,

Ελεύθερος Τύπος, 18 Μαίου 2017, http://www.eleftherostypos.gr/ellada/101257-mazeyoyn-tin-katargisi-tis-istorias-stin-d- dimotikoy/ (τελευταία πρόσβαση 15.02.2018) που σχολίαζαν τα προγράμματα σπουδών της ιστορίας, που προτάθηκαν από το Ινστιτούτο Εκπαιδευτικής Πολιτικής στην Ελλάδα.

[2] For a table of contents, see “Vol 4 (2003)”, Historein, eJournals ePublishing, https://ejournals.epublishing.ekt.gr/index.php/historein/issue/view/152 (last accessed on 15 February 2018).

[3] Antonis Liakos and Mitsos Bilalis, “The Jurassic Park of Historical Culture,” in Palgrave Handbook of Research in Historical Culture and Education, eds. Mario Carretero, Stefan Berger, and Maria Grever (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 207-224.

[4] Frank Ankersmit, Meaning, Truth, and Reference in Historical Representation (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012).

[5] https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/3-2015-2/public-history-sublation-german-debate/#comments (τελευταία πρόσβαση 15.02.2018).

[6] Χάρης Αθανασιάδης, Τα Αποσυρθέντα Βιβλία, Έθνος και Σχολική Ιστορία (1858-2008) (Αθήνα, Αλεξάνδρεια: 2015).

[7] Liakos and Bilalis, “The Jurassic Park of Historical Culture,” 207-224.

[8] Daniel Jacobi, “Les Terminologies et leur Devenir dans les Textes de Vulgarization Scientifique,” Didaskalia 1, no. 3 (1993): 69-82.

[9] Δώρα Κάββουρα, Διδακτική της Ιστορίας, Επιστήμη, Διδασκαλία, Μάθηση (Αθήνα, Μεταίχμιο: 2010).

[10] James Wertsch, Voices of Collective Remembering (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

[11] Eilean Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and Education: Purpose, Pedagogy, Performance (London: Routledge, 2007), 32.

[12] Athanasiadis, Textbooks Withdrawn.

[13] Chris Husbands, What Is History Teaching? (London: Open University Press, 1996), 82.

[14] Hilary Cooper and Arthur Chapman, Constructing History 11-19 (London: Sage, 2009).

[15] Maria Repoussi and Nicole Tutiaux-Guillon, “New Trends in History Textbook Research,” Journal of Educational Media, Memory, and Society 2, no. 1 (2010): 154-170.

[16] Adam Chapman, Digital Games as History: How Videogames Represent the Past and Offer Access to Historical Practice (London: Routledge, 2016).

[17] Liakos and Bilalis, “The Jurassic Park of Historical Culture,” 207-224.

_____________________

Image Credits

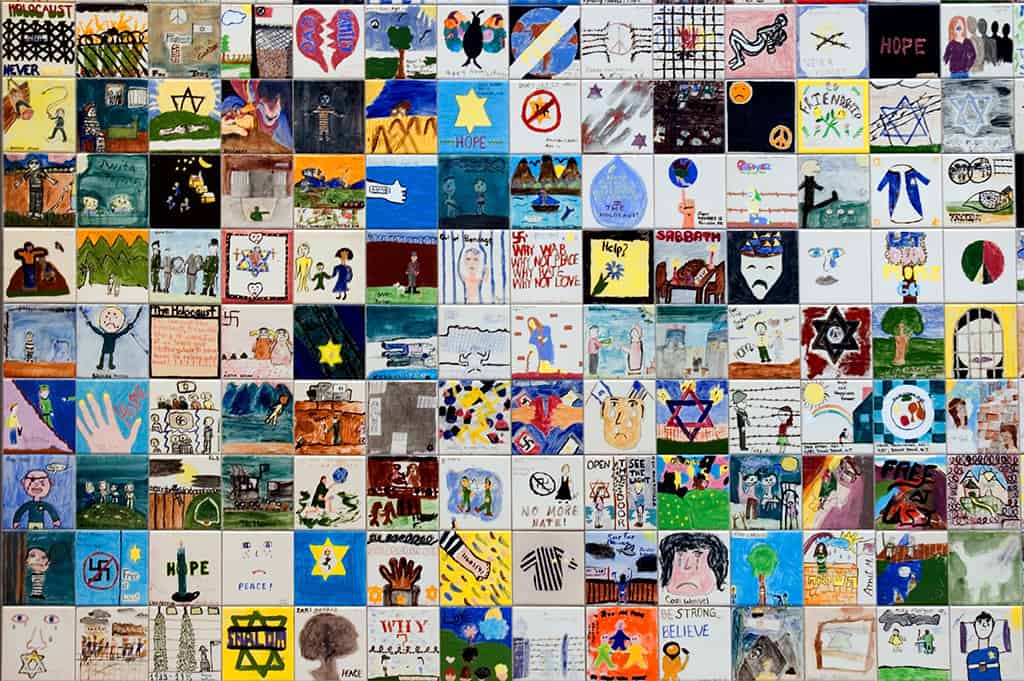

USHMM Wall of Remembrance 3 © paurian via flickr

Recommended Citation

Apostolidou, Eleni: Η Δημόσια Γοητεία της Ιστορικής Εκπαίδευσης. In: Public History Weekly 6 (2018) 10, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-11540.

Whatever the epistemological status of public history or of history didactics might be, public interest in the development of history education cannot be denied. In order to further contribute to the debate about the relationship between history didactics, public history, and historical culture, I would like to identify historical culture as the common denominator of the other two.[1]

History, Public History, Historical Culture

The 2003 issue of the Greek journal Historein was published under the title “Public Histories”,[2] and as the editors suggest it aimed at bringing to the fore the debate about the second life of the past, the past’s revival in the present, and its public—not necessarily its historiographic dimension. As Antonis Liakos and Mitsos Bilalis put it,

“different pasts are reactivated in different circumstances […] and no one knows when [and] under what conditions […] past wars will start [once again].”[3]

This is the reason why the present experience of the past and the ways the past is represented in the present constitute an additional topic for the historian. Liakos and Bilalis therefore cite Ankersmit[4] by writing that “to know history one needs to give priority to the experience of history.”

Commenting on Marko Demantowsky’s article in Public History Weekly, Constantin Goschler emphasizes that public history originated in academia and therefore constitutes a popular product of historiography intended for unexperienced audiences. It also represents history produced from below which would mean the democratization of the historian’s profession as the “monopolies of interpretation” seem to be challenged.[5] While Liakos and Bilalis focus on history in the public and seem to view it as a cultural product to be analyzed by the historian, Goschler maintains that history is produced by or for the public. Using his analysis of the fiercely contested 2006 historical debate about a school textbook in Greece as a starting point, Harris Athanasiadis distinguishes between history produced for the public by academics, history from “below” such as oral history, and—as preferred in his own book—history and historical debates as a field for ethnographic and historical research.[6]

A Long-Lasting Relationship

When reading about the focus of historians in historical culture (as well as the fact that it has substituted historical theory),[7] I could not help but think that history didactics has always shared a very close relationship with historical culture, since—as Daniel Jacobi describes—it takes a “reformulation” of scientific terms to teach inexperienced readers.[8] According to Dora Kavoura, it seems that school or educational culture is influencing the scientific content that is to be taught.[9] Before “New History” in education emerged, sources, iconic or other, were not relevant, with teachers instead being encouraged to use visual means in their classroom. This does not mean that students were expected to develop multiliteracy; in those years, they were passive consumers of the ready-made historical content while maps or other visual means sought to facilitate the “mastery” of such content.[10] From the museums’ perspectives, recognition of the educational value of material culture had taken place as early as during the Middle Ages, when Thomas Aquinas emphasized the value of applying the five senses in learning. Hooper-Greenhill states that “learning is a process of active engagement with experience.”[11]

My point is that school history knowledge has always been scientific knowledge modified to apply to the needs of students and several nation states, as citizenship or patriotism were supposed to develop mainly by teaching history. In that sense it has always been “public” too, meaning that it constitutes a popularization or vulgarization of historical knowledge in order to address pupils of different ages.[12]

What about “New History” or the constructivist paradigm in history education? In his classic book What Is History Teaching? Chris Husbands encourages teachers to use non-formal educational environments such as museums. He explains that

“building interpretations of the past depends on linking what we see to what we already think about the past, to the ideas we, and our children, bring into the museum”.[13]

Students may therefore “reshape their minitheories, misunderstandings” in museums, given that they have enough time to express themselves.[14] In “Constructing History 11-19”, Hilary Cooper and Arthur Chapman use material culture and newspapers to encourage pupils to act as detectives of the past or to make documentaries and websites on their own. All the above are presented as case studies for constructivist exploratory work.[15]

More than ever, history in school is mediated today by historical culture, material culture, digital means, and drama; practices from non-formal educational environments are transferred in school. Even textbooks constituting a traditional educational means have changed:

“[N]ew structural appearances of textbooks [and] iconographic materials come to interrupt the unity of the written text and create a new multimodal text and content,[…] a kind of text that does not give answers but supports the methods of learning and fits in with the laboratory learning environment.”[16]

Finally, in terms of the digital aspect, Chapman concludes that in certain video games it is possible for the players to simulate not only the past but also the discourse about the past. He refers to such games as games of “conceptual” simulation in contrast with games of “realist” simulation, the latter being considered as having adopted a traditional epistemology. In the end, the players are provided with a platform within which they may develop historical arguments.[17]

Conclusion

Both history as historiography and history didactics are “public”: While historians have also been public figures since the nineteenth century,[18] history didactics explores the ways in which teaching becomes more effective. Therefore, both historiography in its public dimension and history didactics may focus on the diffusion of historical knowledge. Historical culture as a learning environment for history didactics, as the sum of the different ways in which the past is recreated in the present (public history), and as one additional cultural expression to be analyzed by historians seems to coincide with academic history and history didactics, which can also be identified with public history in at least one sense.

_____________________

Further Reading

- De Groot, Jerome. Consuming History: Historians and Heritage in Contemporary Popular Culture. London: Routledge, 2008.

- Chapman, Adam. Digital Games as History: How Videogames Represent the Past and Offer Access to Historical Practice. London: Routledge, 2016.

Web Resources

- Europeana Blog. http://blog.europeana.eu/ (last accessed on 15 February 2018).

- Oral History Groups (Athens). http://oralhistorygroups.gr/ (last accessed on 15 February 2018).

_____________________

[1] This article was inspired, amongst others, by two seminars organized by the journal Historein in Athens under the title “Theorizing Historical Culture,” which took place in Athens in May and December 2017. It was also influenced by two articles in Public History Weekly that aimed to define public history as well as its relationship with history didactics: Marko Demantowsky, “‘Public History’ – Sublation of a German Debate?” Public History Weekly 3, no. 2 (2015), dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2015-3292 (last accessed on 15 February 2018); and David Dean and Joanna Wojdon, “Public History and History Didactics – A Conversation,” Public History Weekly 5, no. 9 (2017), dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-8656 (last accessed on 15 February 2018). Finally, it was also inspired by recent comments in the Greek press on the new history education curricula proposed by the Institute of Educational Policy in Greece: Marny Papamathaiou, “Nees alchemeies Gavroglou sto exetastiko,” Ta Nea, 23 November 2017, http://www.tanea.gr/news/greece/article/5489576/nees-alxhmeies-gabrogloy-sto-eksetastiko/ (last accessed on 15 February 2018); and Elpida Oikonomidi, “Mazevoun tin katargisi tis istorias stin D’ Demotikou,” Eleftheros Typos, 18 May 2017, http://www.eleftherostypos.gr/ellada/101257-mazeyoyn-tin-katargisi-tis-istorias-stin-d- dimotikoy/ (last accessed on 15 February 2018).

[2] For a table of contents, see “Vol 4 (2003)”, Historein, eJournals ePublishing, https://ejournals.epublishing.ekt.gr/index.php/historein/issue/view/152 (last accessed on 15 February 2018).

[3] Antonis Liakos and Mitsos Bilalis, “The Jurassic Park of Historical Culture,” in Palgrave Handbook of Research in Historical Culture and Education, eds. Mario Carretero, Stefan Berger, and Maria Grever (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 207-224.

[4] Frank Ankersmit, Meaning, Truth, and Reference in Historical Representation (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012).

[5] Constantin Goschler, 5 February 2015, 4:31 p.m., comment on Public History Weekly, https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/3-2015-2/public-history-sublation-german-debate/#comments (last accessed on 15 February 2018).

[6] Harris Athanasiadis, Τα αποσυρθέντα βιβλία: Έθνος και σχολική ιστορία στην Ελλάδα, 1858-2008 [Textbooks Withdrawn: Nation and School History, 1858-2008] (Athens: Alexandria, 2015).

[7] Liakos and Bilalis, “The Jurassic Park of Historical Culture,” 207-224.

[8] Daniel Jacobi, “Les Terminologies et leur Devenir dans les Textes de Vulgarization Scientifique,” Didaskalia 1, no. 3 (1993): 69-82.

[9] Dora Kavvoura, Didaktiki tis Istorias, Epistemi, Didaskalia, Mathisi (Athens: Metaichmio, 2010).

[10] James Wertsch, Voices of Collective Remembering (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

[11] Eilean Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and Education: Purpose, Pedagogy, Performance (London: Routledge, 2007), 32.

[12] Athanasiadis, Textbooks Withdrawn.

[13] Chris Husbands, What Is History Teaching? (London: Open University Press, 1996), 82.

[14] Chris Husbands (1996), above.

[15] Hilary Cooper and Arthur Chapman, Constructing History 11-19 (London: Sage, 2009).

[16] Maria Repoussi and Nicole Tutiaux-Guillon, “New Trends in History Textbook Research,” Journal of Educational Media, Memory, and Society 2, no. 1 (2010): 154-170.

[17] Adam Chapman, Digital Games as History: How Videogames Represent the Past and Offer Access to Historical Practice (London: Routledge, 2016).

[18] Liakos and Bilalis, “The Jurassic Park of Historical Culture,” 207-224.

_____________________

Image Credits

USHMM Wall of Remembrance 3 © paurian via flickr

Recommended Citation

Apostolidou, Eleni: The Public Lure of History Education. In: Public History Weekly 6 (2018) 10, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-11540.

Was auch immer der epistemologische Status von Public History oder der Geschichtsdidaktik sein mag, das öffentliche Interesse an der Entwicklung der historischen Bildung kann nicht geleugnet werden. Um die Debatte über das Verhältnis zwischen Geschichtsdidaktik, Public History und Geschichtskultur weiter voranzutreiben, möchte ich die Geschichtskultur als gemeinsamen Nenner ausweisen.[1]

Geschichte, Public History, Geschichtskultur

Die 2003 erschienene Ausgabe des griechischen Journals Historein wurde unter dem Titel “Public Histories” herausgegeben[2] und versuchte laut HerausgeberInnen, die Debatte über das zweite Leben der Vergangenheit, das Wiederaufleben der Vergangenheit in der Gegenwart und ihre Öffentlichkeit zu betonen, jedoch nicht notwendigerweise ihre historische Dimension. Wie es Antonis Liakos und Mitsos Bilalis formulieren,

“werden verschiedene Vergangenheiten unter unterschiedlichen Umständen reaktiviert […] und niemand weiß, wann [und] unter welchen Konditionen […] vergangene Kriege [erneut] beginnen werden”.[3]

Deshalb ergeben die gegenwärtige Erfahrung der Vergangenheit und die Art und Weise, wie die Vergangenheit in der Gegenwart repräsentiert wird, ein zusätzliches Thema für HistorikerInnen. Liakos und Bilalis zitieren daher Ankersmit, indem sie schreiben, dass “man, um Geschichte zu kennen, der Erfahrung der Geschichte Priorität verleihen muss”.[4]

Marko Demantowskys Artikel in Public History Weekly kommentierend, betont Constantin Goschler, dass Public History akademischen Kreisen entstammt und deshalb ein gefragtes Produkt der Historiographie für ein unerfahrenes Publikum bildet. Sie repräsentiert auch jene Geschichte von unten, die schließlich die Demokratisierung der HistorikerInnenprofession bedeutet, indem sie die “Monopole der Interpretation” scheinbar in Frage stellt.[5] Während sich Liakos und Bilalis auf die Geschichte im öffentlichen Raum konzentrieren und diese als Kulturprodukt, das von HistorikerInnen analysiert werden soll, betrachten, behauptet Goschler, dass die Geschichte von der Öffentlichkeit oder für diese produziert wird. Harris Athanasiadis, der seine Analyse zur Debatte über ein griechisches Schulbuch im Jahr 2006 als Ausgangspunkt verwendet, unterscheidet zwischen der von AkademikerInnen für die Öffentlichkeit produzierten Geschichte, der Geschichte von “unten” wie zum Beispiel Oral History und – was in seinem Buch bevorzugt wird – der Geschichte und historischen Debatten als Forschungsgebiet für Ethnographie und Geschichtswissenschaft.[6]

Ein langlebiges Verhältnis

Als ich über die Schwerpunktsetzungen von HistorikerInnen in der Geschichtskultur las (und über die Tatsache, dass historische Theorien von dieser ersetzt wurden),[7] wurde mir bewusst, dass die Geschichtsdidaktik schon immer ein sehr enges Verhältnis zur Geschichtskultur hatte: Denn es bedarf laut Daniel Jacobi einer “Neuformulierung” wissenschaftlicher Begriffe, um unerfahrene LeserInnen zu bilden.[8] Dora Kavoura zufolge scheint die schulische und pädagogische Kultur den wissenschaftlichen Inhalt, der gelehrt werden soll, zu beeinflussen.[9] Vor der Entstehung der “Neuen Geschichte” im Bildungswesen waren ikonische oder andere Quellen nicht relevant; stattdessen wurden LehrerInnen dazu ermutigt, visuelle Materialien in ihren Klassenzimmern zu verwenden. Das bedeutet nicht, dass SchülerInnen multiple Kompetenzen entwickeln mussten; damals waren sie passive KonsumentInnen des gebrauchsfertigen Geschichtsinhalts, während Landkarten oder andere visuelle Mittel das “Meistern” solchen Inhalts zu erleichtern versuchten.[10] Aus einer museologischen Perspektive fand die Anerkennung des pädagogischen Wertes der Sachkultur bereits während des Mittelalters statt, als Thomas von Aquin den Wert der Sinne beim Lernen hervorhob. Hooper-Greenhill erklärt, dass “das Lernen ein Prozess aktiven Engagements mit der Erfahrung ist”.[11]

Damit will ich sagen, dass das schulische Geschichtswissen schon immer wissenschaftliches Wissen modifizierte, um den Bedürfnissen der SchülerInnen und zahlreicher Nationalstaaten gerecht zu werden, da Nationalität und Patriotismus hauptsächlich durch das Lernen von Geschichte entwickelt werden sollten. In diesem Sinne war schulisches Geschichtswissen auch immer “öffentlich”, was bedeutet, dass es eine Popularisierung oder Vulgarisierung historischen Wissens darstellt, um SchülerInnen unterschiedlichen Alters zu adressieren.[12]

Was ist mit der “Neuen Geschichte” oder dem konstruktivistischen Paradigma in der Geschichtsbildung? In seinem klassischen Buch What Is History Teaching? ermutigt Chris Husbands LehrerInnen, informelle Bildungsumfelder wie Museen zu nützen. Er erklärt, dass

“das Bilden von Interpretationen zur Vergangenheit davon abhängt, was wir mit dem was wir sehen und bereits von der Vergangenheit denken, also die Ideen mit denen wir, und unsere Kinder, ins Museum gehen, verbinden”.[13]

Daher können SchülerInnen in Museen “ihre Minitheorien, ihre Missverständnisse, neu formen”, vorausgesetzt sie haben genug Zeit, um sich auszudrücken.[14] In “Constructing History 11-19” verwenden Hilary Cooper und Arthur Chapman Sachkultur und Zeitungen, um SchülerInnen zu ermutigen, als DetektivInnen der Vergangenheit zu agieren oder um eigene Dokumentationen und Internetseiten zu entwickeln. All das sind Fallbeispiele für konstruktivistisches, exploratives Arbeiten.[15]

Mehr denn je wird Geschichte in der Schule heutzutage durch die Geschichtskultur, die Sachkultur, digitale Mittel und Theaterstücke vermittelt; Praktiken informeller Bildungsumfelder werden in Schulen weitergeführt. Sogar Schulbücher, die traditionelle erzieherische Mittel darstellen, haben sich verändert:

“[N]eue strukturelle Erscheinungen von Büchern [und] ikonographische Materialen unterbrechen letztlich die Einheit des geschriebenen Textes und kreieren einen neuen multimodalen Text und Inhalt, […] eine Textart, die keine Antworten bietet, sondern die Lernmethoden unterstützt und sich für eine gute Lernatmosphäre eignet.”[16]

Was das Digitale anbelangt, schlussfolgert Chapman letztlich, dass es in gewissen Computerspielen für die SpielerInnen möglich ist, nicht nur die Vergangenheit, sondern auch den Diskurs über diese zu simulieren. Er bezeichnet solche Spiele als Spiele “konzeptueller” Simulation im Vergleich zu Spielen “realistischer” Simulation, wobei letztere eine traditionelle Epistemologie übernommen haben dürfte. Letztlich bieten manche Computerspiele den SpielerInnen eine Plattform, auf der sie historische Argumente entwickeln können.[17]

Fazit

Sowohl Geschichte als Historiographie als auch Geschichtsdidaktik sind “öffentlich”: Während HistorikerInnen seit dem neunzehnten Jahrhundert auch Persönlichkeiten des öffentlichen Lebens sind,[18] erforscht die Geschichtsdidaktik Methoden, wie das Lehren effektiver wird. Deshalb können sich sowohl die Historiographie in ihrer öffentlichen Dimension als auch die Geschichtsdidaktik mit der Diffusion historischen Wissens beschäftigen. Die Geschichtskultur als Lernumgebung für die Geschichtsdidaktik, als die Summe der verschiedenen Methoden, in denen die Vergangenheit in der Gegenwart (Public History) rekonstruiert wird, und als ein zusätzlicher kultureller Ausdruck, der von HistorikerInnen analysiert wird, scheint sich mit der akademischen Geschichte und der Geschichtsdidaktik zu decken, welche in wenigstens einem Aspekt auch mit der Public History identifiziert werden kann.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- De Groot, Jerome. Consuming History: Historians and Heritage in Contemporary Popular Culture. London: Routledge, 2008.

- Chapman, Adam. Digital Games as History: How Videogames Represent the Past and Offer Access to Historical Practice. London: Routledge, 2016.

Webressourcen

- Europeana Blog. http://blog.europeana.eu/ (letzter Zugriff am 15.02.2018).

- Oral History Groups (Athen). http://oralhistorygroups.gr/ (letzter Zugriff am 15.02.2018).

_____________________

[1] Dieser Artikel wurde unter anderem von zwei Seminaren inspiriert, welche vom Journal Historein in Athen unter dem Titel “Die Theoretisierung der Geschichtskultur”organisiert und im Mai und Dezember 2017 in Athen durchgeführt wurden. Er wurde auch von zwei Artikeln aus Public History Weekly beeinflusst, die sowohl die öffentliche Geschichte als auch ihr Verhältnis zur Geschichtsdidaktik definieren sollten: Marko Demantowsky, “‘Public History’ – Sublation of a German Debate?” Public History Weekly 3, no. 2 (2015), dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2015-3292 (letzter Zugriff am 15.02.2018); und David Dean und Joanna Wojdon, “Public History and History Didactics – A Conversation,” Public History Weekly 5, no. 9 (2017), dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-8656 (letzter Zugriff am 15.02.2018). Zuletzt wurde er ebenso durch jüngste Kommentare der griechischen Presse bzgl. Des neuen Geschichtscurriculums, das vom Institut der griechischen Bildungspolitik empfohlen wurde, inspiriert: Marny Papamathaiou, “Nees alchemeies Gavroglou sto exetastiko,” Ta Nea, 23.11.2017, http://www.tanea.gr/news/greece/article/5489576/nees-alxhmeies-gabrogloy-sto-eksetastiko/ (letzter Zugriff am 15.02.2018); und Elpida Oikonomidi, “Mazevoun tin katargisi tis istorias stin D’ Demotikou,” Eleftheros Typos, 18.05.2017, http://www.eleftherostypos.gr/ellada/101257-mazeyoyn-tin-katargisi-tis-istorias-stin-d- dimotikoy/ (letzter Zugriff am 15.02.2018).

[2] Für ein Inhaltsverzeichnis, siehe “Vol 4 (2003)”, Historein, eJournals ePublishing, https://ejournals.epublishing.ekt.gr/index.php/historein/issue/view/152 (letzter Zugriff am 15.02.2018).

[3] Antonis Liakos und Mitsos Bilalis, “The Jurassic Park of Historical Culture,” in Palgrave Handbook of Research in Historical Culture and Education, Hrsg. Mario Carretero, Stefan Berger und Maria Grever (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 207-224.

[4] Frank Ankersmit, Meaning, Truth, and Reference in Historical Representation (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012).

[5] Constantin Goschler, 5.02.2015, 16:31 Uhr, Kommentar in Public History Weekly, https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/3-2015-2/public-history-sublation-german-debate/#comments (letzter Zugriff am 15.02.2018).

[6] Harris Athanasiadis, Τα αποσυρθέντα βιβλία: Έθνος και σχολική ιστορία στην Ελλάδα, 1858-2008 [Textbooks Withdrawn: Nation and School History, 1858-2008] (Athens: Alexandria, 2015).

[7] Liakos and Bilalis, “The Jurassic Park of Historical Culture,” 207-224.

[8] Daniel Jacobi, “Les Terminologies et leur Devenir dans les Textes de Vulgarization Scientifique,” Didaskalia 1, no. 3 (1993): 69-82.

[9] Dora Kavvoura, Didaktiki tis Istorias, Epistemi, Didaskalia, Mathisi (Athens: Metaichmio, 2010).

[10] James Wertsch, Voices of Collective Remembering (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

[11] Eilean Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and Education: Purpose, Pedagogy, Performance (London: Routledge, 2007), 32.

[12] Athanasiadis, Textbooks Withdrawn.

[13] Chris Husbands, What Is History Teaching? (London: Open University Press, 1996), 82.

[14] Ebenda.

[15] Hilary Cooper and Arthur Chapman, Constructing History 11-19 (London: Sage, 2009).

[16] Maria Repoussi and Nicole Tutiaux-Guillon, “New Trends in History Textbook Research,” Journal of Educational Media, Memory, and Society 2, no. 1 (2010): 154-170.

[17] Adam Chapman, Digital Games as History: How Videogames Represent the Past and Offer Access to Historical Practice (London: Routledge, 2016).

[18] Liakos and Bilalis, “The Jurassic Park of Historical Culture,” 207-224.

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

USHMM Wall of Remembrance 3 © paurian via flickr

Übersetzung

Stefanie Svacina and Paul Jones (paul.stefanie@outlook.at)

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Apostolidou, Eleni: Der öffentliche Anreiz der Geschichtsbildung. In: Public History Weekly 6 (2018) 10, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-11540.

Copyright (c) 2018 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 6 (2018) 10

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-11540

Tags: Historical Culture (Geschichtskultur), History Didactics (Geschichtsdidaktik), Language: Greek, Public History