Abstract: Whilst war remembrance in New Zealand is dominated by ANZAC and Gallipoli, there is a growing momentum to commemorate the colonial wars of the 19th century between indigenous Māori and the British/colonial forces. This raises questions about how post-colonial nations such as New Zealand address the difficult features of their past as well as ensure that young people engage with different perspectives on war remembrance that are inclusive of difference and encourage them to think critically about such issues.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-5998.

Languages: English, Deutsch

Whilst war remembrance in New Zealand is dominated by ANZAC and Gallipoli, there is a growing momentum to commemorate the colonial wars of the 19th century between indigenous Māori and the British/colonial forces. This raises questions about how post-colonial nations such as New Zealand address the difficult features of their past as well as ensure that young people engage with different perspectives on war remembrance that are inclusive of difference and encourage them to think critically about such issues.

Waimarama Anderson und Leah Bell

War remembrance in New Zealand is closely aligned with an ideal of ANZAC[1] identity that primarily focuses on this country’s part in the unsuccessful attempt by the Allies in 1915 to invade the Gallipoli peninsula, the sovereign territory of what is now Turkey.

However, there is a growing momentum to also commemorate the colonial wars of the 19th century between Māori[2] and the British/colonial forces[3] and this has recently gained traction from an unexpected quarter. During 2015, two senior secondary school students (Waimarama Anderson and Leah Bell) from a small provincial college in the North Island initiated a petition that called for a national day of commemoration for the New Zealand Land wars. The petition wants to ‘memorialise those who gave their lives on New Zealand soil’ and pleads for this to be more widely taught in schools.[4] While a minority of critics argue that this is grievance history (and New Zealand needs to embrace the future rather than dwelling on the past[5]), the initiative has garnered considerable support, in principle, across the political spectrum.[6] It has been signed by over 12000 signatories and is now before a parliamentary select committee considering this question.

Historical amnesia and a high autonomy curriculum

The petition raises questions about how post-colonial nations like New Zealand address the difficult aspects of their history. Although an increasing number of history teachers prioritise the colonial wars in their programmes, few young New Zealanders learn about the contentious aspects of their past in schools. History, as a discipline-informed subject, is only offered as an elective in the senior school and is studied by a minority of students. The high autonomy curriculum model that operates in New Zealand sees little prescribed content and, because schools are self-managing, they are able to choose what they teach. Typically, schools either veer away from the contentious aspects of New Zealand’s past or see it as not relevant to their community. The reluctance to engage with the controversial aspects of New Zealand’s past is not new. It has been a feature of New Zealand education for decades.[7]

The position of the Education Ministry is to encourage rather than direct. While it supports the idea of teaching about the New Zealand wars with appropriate resources, it will not make the topic compulsory.[8]

“What we are not doing – and are not going to do – is make this or any other topic compulsory. The National Curriculum is a framework for schools and kura[9]. It provides them with guidance on covering key learning areas and designing their own curriculum. How they do that and what they include in their curriculum should be for them to decide, in consultation with their local community.”[10]

Although the colonisation experience is a core feature of renegotiating the relationship between Māori and non-indigenous New Zealanders, the ‘hands off’ model promulgated by the Ministry of Education is unlikely to result in young people learning about the colonial wars (or other contested aspects of this country’s past).

There is no shortage of resources to teach about New Zealand history.[11] Rather, what is needed is a shift in thinking that sees the history of this place as a priority for young New Zealanders to understand if they are to engage with 21st century society as critically informed citizens.

A critically informed approach to war remembrance

Engaging young people with a critically informed understanding of New Zealand’s past is not a simple process. Aside from the question of the controversial nature of this history, young people are typically encouraged in their schooling to approach topics to do with war remembrance with a reverence for those who died (or served) and they are reluctant to consider the complexity of these events or address the difficult aspects – an approach that is potentially exclusive and discourages opportunities for meaningful critique.

In New Zealand, how we commemorate the military pacification of Māori opposition to the British colonisation that saw (in breach of the guarantees of the Treaty of Waitangi[12]) the confiscation of Māori lands and a series of wars that included human rights abuses on both sides, is not simply a matter of a teaching a received narrative. What is needed is space for different perspectives on war remembrance that are inclusive of difference and that allow young people to think critically about the significance of the Colonial wars of the 19th century, rather than simply approaching the question of the land wars through the lens of memory, as is presented in the petition:

“In our country we do not commemorate those who lost their lives here in New Zealand, both Māori and colonialists. Their blood was shed on New Zealand soil; their lives were given in service to New Zealand … New Zealand cannot afford to forget the ultimate sacrifice of the soldiers and warriors on the plains, coasts, hilltops and valleys of our great Nation.”[13]

The petition, however, has achieved what was largely unthinkable even a decade ago: a parliamentary select committee considering how this country should address the contentious aspects of its past. It has a long way to go but the instigators have laid down a challenge to their elders and, as they say, “what we are doing now is a starting point for a historically conscious future.”[14]

_____________________

Further Reading

- Anderson, A., Binney, J., Harris, Aroma (2014). Tangata Whenua, Bridget Williams Books, Wellington.

- Binney, J. (2009). History and Memory: The Wood of the Whau Tree, 1766–2005. In: Giselle Byrnes (ed.), The New Oxford History of New Zealand, Melbourne, Oxford University Press, pp. 73–98 & 614–19.

- Harcourt, M., Sheehan, M. (eds.) (2012). History Matters: Teaching and Learning history in 21st New Zealand. NZCER Press: Wellington.

Web Resources

- New Zealand Wars memorials http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/war/new-zealand-wars-memorials (last accessed 11/04/16).

- Story: New Zealand Wars: http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/new-zealand-wars/page-11 (last accessed 11/04/16).

- The New Zealand Wars: http://www.newzealandwars.co.nz (last accessed 11/04/16).

__________________

[1] ANZAC: Australian and New Zealand Army Corp: the acronym for New Zealand and Australian soldiers who fought during the First World War.

[2] Māori are the indigenous, first inhabitants of New Zealand who are the descendants of Polynesian settlers who arrived approximately 800 years ago. New Zealanders who claim Māori ancestry currently make up around 10-15% of the population.

[3] http://www.e-tangata.co.nz/news/why-do-we-ignore-the-new-zealand-wars (last accessed 11/04/16)

[4] http://www.parliament.nz/en-nz/pb/sc/make-submission (last accessed 9/04/16)

[5] http://www.nzcpr.com/tribal-rebellions-day-indoctrination-not-wanted/ (last accessed 31/03/2016)

[6] http://www.maoritelevision.com/news/national/nz-land-wars-petition-gains-political-s (last accessed 25/03/16).

[7] Sheehan, M. (2011) ‘Little is taught or learned in schools’ Debates over the place of history in the New Zealand school Curriculum. In Robert Guyver and Tony Taylor (eds.) History Wars in the Classroom: a global perspective, Information Age Publishing, Charlotte, North Carolina, pp. 104-127; Sheehan, M. (2010). The place of ‘New Zealand’ in the New Zealand history curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies 42:5, pp. 671-691.

[8] Karl Le Quesne; Kiritina Johnstone (Ministry of Education): http://www.radionz.co.nz/news/te-manu-korihi/300262/should-teaching-nz-wars-be-re (last accessed 31/03/2016).

[9] Māori medium schools.

[10] Lisa Rodgers (Ministry of Education): Dominion Post (9th April 2016): Letter to editor

[11] For example see: http://nzhistory.net; http://www.teara.govt.nz (last accessed 11/4/16).

[12] Signed first at Waitangi in the north of New Zealand in February 1840, the Treaty of Waitangi was a pact between the British Crown and Māori chiefs. Māori ceded sovereignty to the British in return for guarantees they could retain particular privileges and rights over their lands and fisheries.

[13] Leah Bell and Waimarama Anderson (Otorohanga College), http://www.petitionbuzz.com/petitions/nzlandwars1963/ (last accessed 14/03/2016).

[14] https://www.hrc.co.nz/news/petition-remember-nz-land-wars/ (last accessed 18/03/2016).

_____________________

Image Credits

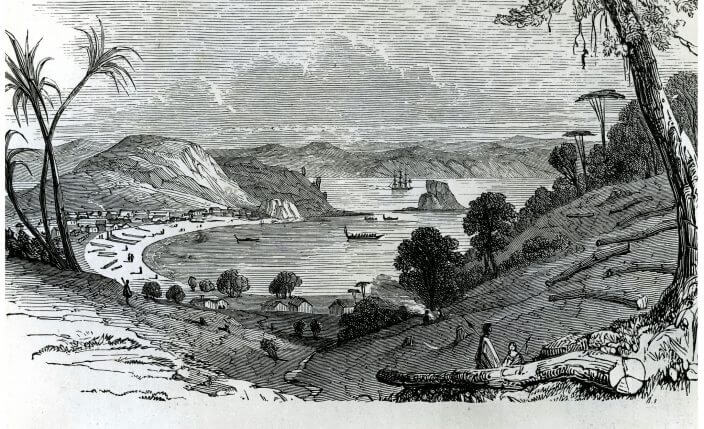

Drawing (1844) of Kororāreka (Russell), Bay of Islands around the time of the Northern War (Flagstaff War) (@ Flickr). © Archives New Zealand with CC BY-SA 2.0; cf. www.nzhistory.net.nz/war/northern-war.

Kororāreka (in the Northern part of the New Zealand) was the center of European settlement in the early 19th century. Although it had a reputation as a lawless frontier town, relations with Maori were initially positive until the mid 1840s. Kororareka then became the center of the Northern war between British and local Maori. Opposition to the government (and its Maori allies) was led by the chief Hone Heke who saw the British as eroding the authority of his people to retain control over their lands and resources as guaranteed by the Treaty of Waitangi.

Recommended Citation

Sheehan, Mark: “A historically conscious future” – Indigenous perspectives on war remembrance. In: Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 15, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-5998.

Obwohl das Kriegsgedenken in Neuseeland von ANZAC und Gallipoli dominiert werden, gibt es zunehmend den Wunsch, auch der kolonialen Kriege zwischen den Māori und den britisch-kolonialen Streitkräften im 19. Jahrhundert zu gedenken. Dies wirft Fragen danach auf, wie postkoloniale Länder wie Neuseeland die komplexen Merkmale ihrer Vergangenheit thematisieren und dabei sicherstellen, dass sich junge Menschen mit den unterschiedlichen Perspektiven auf dieses Kriegsgedenken auseinandersetzen, die die Unterschiede einschliessen und dazu ermuntern, kritisch über solche Themen nachzudenken.

Waimarama Anderson und Leah Bell

Kriegsgedenken in Neuseeland richtet sich eng an einem Ideal der ANZAC[1]-Identität aus. Dessen primärer Fokus liegt auf der Rolle des Landes beim erfolglosen Versuch der Entente, 1915 die Halbinsel Gallipoli zu besetzen; ein Gebiet, das heute zur Türkei gehört.

Jedoch wächst der Wunsch, auch der Kolonialkriege des 19. Jahrhunderts zwischen den Māori[2] und den britisch-kolonialen Streitkräften zu gedenken und dieser Wunsch hat in jüngster Zeit Unterstützung aus einer unerwarteten Ecke erhalten. Im vergangenen Jahr haben zwei Oberstufen-Schülerinnen (Waimarama Anderson und Leah Bell), die in einem kleinen Provinz-College auf der Nordinsel zur Schule gehen, eine Petition verfasst, die dazu aufruft, einen nationalen Gedenktag für die Landkriege Neuseelands einzurichten. Die Petition möchte an diejenigen erinnern, die ihr Leben auf neuseeländischem Boden verloren haben, und wirbt dafür, diese Geschehnisse in größerem Umfang an den Schulen zu unterrichten.[4] Obwohl eine Minderheit von KritikerInnen die Ansicht vertreten, dass es sich hier um eine “Klage-Geschichte” handle (und Neuseeland eher die Zukunft willkommen heißen solle, statt über die Vergangenheit zu grübeln[5]), hat die Petition beträchtliche Unterstützung gesammelt, und zwar im Prinzip aus dem gesamten politischen Spektrum.[6] Sie hat mehr als 12’000 UnterzeichnerInnen gefunden und liegt jetzt bei einem parlamentarischen Sonderausschuss, der diese Frage prüft.

Historische Amnesie und ein autonomes Curriculum

Die Petition wirft Fragen auf, wie postkoloniale Länder wie Neuseeland mit den schwierigen Aspekten ihrer Geschichte umgehen. Obwohl eine zunehmende Zahl von GeschichtslehrerInnen den kolonialen Kriegen Priorität in ihren Planungen einräumen, lernen nur wenige junge NeuseeländerInnen etwas über die umstrittenen Seiten ihrer Geschichte in der Schule. Geschichte, ein fachwissenschaftlich basiertes Fach, wird in der Oberstufe nur als Wahlfach angeboten und wird nur von einer Minderheit der SchülerInnen gewählt. Das Modell eines autonomen Curriculums, das Neuseeland verwendet, schreibt nur wenige Pflichtinhalte vor; und da die Schulen selbstverwaltet sind, können sie selbst bestimmen, was sie unterrichten. Üblicherweise weichen Schulen entweder den umstrittenen Aspekten der neuseeländischen Vergangenheit aus, oder sie sehen diese als für ihre Gemeinschaft irrelevant an. Die Abneigung, sich mit kontroversen Aspekten der neuseeländischen Geschichte zu beschäftigen, ist nicht neu. Sie ist seit Jahrzehnten ein Merkmal der Bildungspolitik des Landes.[7]

Die Haltung des Bildungsministeriums ist, zu ermuntern statt zu dirigieren. Es unterstützt zwar den Ansatz, Unterricht zu den neuseeländischen Kriegen anzubieten, wird das Thema aber nicht verpflichtend machen.[8]

“Was wir nicht tun – und nicht tun werden – ist dieses Thema oder irgendwelche andere Themen für obligatorisch zu erklären. Das nationale Curriculum stellt einen Orientierungsrahmen für Schulen und Kura[9] dar. Es bietet ihnen Hilfestellung zur Behandlung von wesentlichen Lerngebieten und zur Ausgestaltung ihres eigenen Curriculums. Wie sie dies machen und was sie in das Curriculum aufnehmen, sollen sie in Absprache mit ihrer lokalen Gemeinschaft selbst entscheiden.”[10]

Obwohl die Erfahrung der Kolonisation ein Kernstück der Neuverhandlungen darstellt, mit denen die Beziehung zwischen den Māori und den nichtindigenen Neuseeländern geklärt werden soll, wird das vom Bildungsministerium angewandte Modell der “Nichteinmischung” wahrscheinlich nicht dazu führen, dass junge Menschen etwas über die Kolonialkriege (oder andere umstrittene Aspekte der Vergangenheit des Landes) lernen werden.

Dabei mangelt es nicht an Ressourcen, die Geschichte Neuseelands zu unterrichten.[11] Vielmehr braucht es eine Änderung im Denken: Es muss als Priorität betrachtet werden, dass junge NeuseeländerInnen die Landesgeschichte verstehen, damit sie sich als kritische, informierte BürgerInnen an der Gesellschaft des 21. Jahrhunderts beteiligen können.

Ein kritisch aufgeklärter Zugang zu Kriegsgedenken

Dafür zu sorgen, dass sich junge Menschen mit einem kritisch aufgeklärten Verständnis mit der Vergangenheit Neuseelands auseinandersetzen, ist kein einfacher Prozess. Abgesehen von der kontroversen Natur dieser Geschichte werden junge Menschen während ihrer Schulzeit üblicherweise ermuntert, Themen in Bezug auf das Kriegsgedenken vorrangig so zu behandeln, dass jene geehrt werden, die gefallen sind (oder im Militär gedient haben). Sie widerstreben dem Anliegen, die Komplexität dieser Ereignisse zu bedenken oder die schwierigen Aspekte zu betrachten. So etabliert sich ein Ansatz von Kriegsgedenken, der potenziell ausschliessend ist und Gelegenheiten für sinnstiftende Kritik verhindert.

Bei der Art, wie wir in Neuseeland der militärischen Befriedung des Māori-Widerstands gegen die britische Kolonisierung gedenken, die (entgegen den Garantien im Vertrag von Waitangi [12]) die Enteignung von Māori-Landstrichen und eine Reihe von Kriegen zur Folge hatte, in denen auf beiden Seiten Menschenrechte verletzt wurden, geht es nicht einfach darum, wie ein anerkanntes Narrativ unterrichtet wird. Es braucht Raum für unterschiedliche Perspektiven auf das Kriegsgedenken, die Unterschiede einschließen und jungen Menschen ermöglichen, kritisch über die Bedeutung der kolonialen Kriege des 19. Jahrhunderts nachzudenken, statt die Frage der Landkriege einfach durch die Linse der Erinnerung zu betrachten, wie dies in der Petition vorgestellt wird:

“In unserem Land gedenken wir nicht derjenigen, seien es Māori oder Kolonialisten, die ihr Leben hier in Neuseeland verloren. Ihr Blut wurde auf neuseeländischem Boden vergossen; sie starben im Dienste Neuseelands … Neuseeland kann es sich nicht leisten, das höchste Opfer der Soldaten und Krieger auf den Ebenen, Küsten, Bergkuppen und Tälern unserer großen Nation zu vergessen.”[13]

Die Petition hat dennoch etwas geschafft, was noch vor einem Jahrzehnt praktisch undenkbar gewesen wäre: Ein parlamentarischer Sonderausschuss überlegt, wie dieses Land mit den umstrittenen Aspekten seiner Vergangenheit umgehen soll. Der Weg ist noch lang, doch die Initiatorinnen haben die Älteren vor eine Herausforderung gestellt und, wie sie sagen: “Was wir jetzt tun, ist ein Ausgangspunkt für eine historisch bewusste Zukunft.”[14]

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Anderson, Atholl / Binney, Judith / Harris, Aroha: Tangata Whenua, Wellington 2014.

- Binney, Judith: History and Memory: The Wood of the Whau Tree, 1766–2005. In: Byrnes, Giselle (Hrsg.): The New Oxford History of New Zealand, Melbourne 2009, S. 73-98, 614-619.

- Harcourt, Michael / Sheehan, Mark (Hrsg.): History Matters: Teaching and Learning history in 21st New Zealand, Wellington 2012.

Webressourcen

- New Zealand Wars memorials: http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/war/new-zealand-wars-memorials (letzter Zugriff 11.04.16).

- Story: New Zealand Wars: http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/new-zealand-wars/page-11 (letzter Zugriff 11.04.16).

- The New Zealand Wars: http://www.newzealandwars.co.nz (letzter Zugriff 11.04.16).

__________________

[1] ANZAC: Australian and New Zealand Army Corp: das Akronym für neuseeländische und australische Soldaten, die im 1. Weltkrieg kämpften.

[2] Māori sind die indigenen ersten Bewohner Neuseelands, Abkömmlinge der polynesischen Siedler, die vor etwa 800 Jahren dort ankamen. NeuseeländerInnen mit Māori-Abstammung bilden aktuell ca. 10-15% der Bevölkerung.

[3] www.e-tangata.co.nz/news/why-do-we-ignore-the-new-zealand-wars (letzter Zugriff: 11/04/16).

[4] http://www.parliament.nz/en-nz/pb/sc/make-submission (letzter Zugriff: 9/04/16).

[5] http://www.nzcpr.com/tribal-rebellions-day-indoctrination-not-wanted/ (letzter Zugriff: 31/03/2016).

[6] http://www.maoritelevison.com/news/national/nz-land-wars-petition-gains-political-s (letzter Zugriff: 25/03/16).

[7] Sheehan, M. (2011) ‘Little is taught or learned in schools’ Debates over the place of history in the New Zealand school Curriculum. In Robert Guyver and Tony Taylor (eds.) History Wars in the Classroom: a global perspective, Information Age Publishing, Charlotte, North Carolina, pp. 104-127; Sheehan, M. (2010). The place of ‘New Zealand’ in the New Zealand history curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies 42:5, pp. 671-691.

[8] Karl Le Quesne; Kiritina Johnstone (Ministry of Education): http://www.radionz.co.nz/news/te-manu-korihi/300262/should-teaching-nz-wars-be-re (letzter Zugriff: 31/03/2016)

[9] Schulen mit Unterricht in der Sprache der Māori.

[10] Lisa Rodgers (Ministry of Education): Dominion Post (9th April 2016): Letter to editor

[11] For example see: http://nzhistory.net; http://www.teara.govt.nz (letzter Zugriff: 11/4/16).

[12] Unterzeichnet in Waitangi in Nordneuseeland in Februar 1840, war der Vertrag von Waitangi ein Pakt zwischen der britischen Krone und Māori-Ältesten. Die Māori tauschten Gebietshoheit gegen Garantien, dass sie bestimmte Vorteile und Rechte in Bezug auf Böden und Fischerei behielten.

[13] Leah Bell and Waimarama Anderson (Otorohanga College), http://www.petitionbuzz.com/petitions/nzlandwars1963/ (letzter Zugriff: 14/03/2016).

[14] https://www.hrc.co.nz/news/petition-remember-nz-land-wars/ (letzter Zugriff: 18/03/2016).

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

Zeichnung (1844) von Kororāreka (Russell), Bay of Islands, zur Zeit des Kriegs auf der Nordinsel Neuseelands (Northern War; Flagstaff War) (@ Flickr). © Archives New Zealand unter CC BY-SA 2.0; vgl. www.nzhistory.net.nz/war/northern-war.

Kororāreka (auf der Nordinsel von Neuseeland) war das Zentrum der europäischen Siedlung im frühen 19. Jahrhundert. Obwohl es den Ruf einer gesetzlosen Frontier-Stadt hatte, waren die Beziehungen zu den Maori bis in die 1840er-Jahre zunächst positiv. Dann wurde Kororāreka zum Zentrum der kriegerischen Auseinandersetzungen des “Northern war” zwischen britischen Truppen und Maori. Der Widerstand gegen die britische Regierung (und die verbündeten Maori) wurde von Chief Hone Heike angeführt. Er fürchtete, dass die Ansprüche der britischen Regierung die Autorität der von ihm repräsentierten Maori untergrabe in Bezug auf die Kontrolle über Land und Ressourcen, wie sie im Vertrag von Waitingi garantiert worden waren.

Übersetzung

Jana Kaiser: kaiser (at) academic-texts.de

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Sheehan, Mark: “Eine historisch bewusste Zukunft” – Indigene Perspektiven auf Kriegsgedenken. In: Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 15, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-5998.

Copyright (c) 2016 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 4 (2016) 15

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-5998

Tags: Colonial Legacy (Koloniales Erbe), Curriculum (Lehrplan), Erinnerungskultur (Culture of Remembrance), New Zealand (Neuseeland), Postcolonial Perspectives

As Mark Sheehan acknowledges, the actions of Waimarama Anderson and Leah Bell are to be commended. These students have provided the stimulus for necessary conversations about New Zealanders’ relationship to contentious aspects of the past. Sheehan is equally correct in expressing concern over aspects of the petition, and the Ministry of Education’s response to it.

The petition’s claim that “New Zealand cannot afford to forget the ultimate sacrifice of the soldiers and warriors on the plains, coasts, hilltops and valleys of our great Nation” stands out for its similarity to uncritical, nationalist commemorations of World War One prevalent in New Zealand at the moment. The students may have deliberately couched their petition in these terms to gain public support and approval. But as a platform for history education, such sentiments do not support critical historical thinking. Also problematic is the Ministry of Education’s “hands off approach”. The high autonomy offered by the New Zealand Curriculum has allowed many teachers to construct their programmes according to student interest. Appealing to interest in programme design is not wrong, but it is unlikely to result in students choosing contested, uncomfortable history, the consequences of which linger in the present. Teachers need to be proactive in designing programmes according to what students need, as well as what they want. If the curriculum autonomy entrusted to schools results in the avoidance of contentious aspects of the past the Ministry of Education has to reconsider its current position.

However, in his argument Sheehan hasn’t addressed the risks inherent in mandating any subject matter, no matter how commendable it may seem. Yes, the government should work harder to ensure New Zealand schools incorporate the New Zealand Wars and other contentious topics into their curriculum. But there is significant risk of greater ministerial direction resulting in exactly what Sheehan fears – the teaching of a received narrative through the lens of memory. It is precisely the local control given to schools to choose their curriculum content which makes possible a more nuanced, place-based approach capable of incorporating local indigenous perspectives – perspectives that can be silenced by nationalist “best story” narratives of the past. Sheehan would probably correctly argue that such silencing is already taking place in New Zealand because the freedom-to-choose, ‘encourage not direct’ model supported by the Ministry of Education enables schools to avoid the teaching of so-called “difficult history”.

Is there a middle ground between New Zealand’s high autonomy model and jurisdictions which mandate a content heavy, centrally prescribed common core? If so, what does it look like in a New Zealand context and how could it be implemented? Teachers, educationalists and Ministry of Education officials need to give greater attention to these kinds of questions if we are serious about supporting young New Zealanders in all schools to grapple with contentious historical topics and indigenous perspectives on war and remembrance.

Michael and Mark have made some interesting comments. Personally I have found that many students are captivated by the stories within our colonial past. These are narratives that they generally know nothing about because of the lack of History teaching in the Primary and early Secondary syllabus. As a result they would almost never choose this history because their interests have already been captured by Hollywood and the History Channel. I choose to teach our colonial past because I love to open their eyes to the events that shaped our society with all of its flaws exposed. Heroism, chivalry massacre, cannibalism, cowardice and greed all abound in this period, in this place. I also have links to both sides of the conflict and can mix these stories into my lessons.

I’m not sure that our Ministry should mandate topics for the same reason that Michael has suggested, but I would urge all History departments to encourage the teaching of this period and to allow students to explore the challenging nature of the subject.

I support encouraging serious study of the Wars and their context but not at the cost of re-introducing prescribed content.

Dr Sheehan talks of a “high autonomy curriculum model” and implies it is the problem. I take issue with this. I don’t see schools “typically” veering away from contentious issues. That may be the case for some, but a glance at history teacher forums shows many are taking on contested contexts and discussing ways and means of doing so. The paucity of opportunities to do so as professional learning opportunities are reduced and rationed through selected agencies delivering courses on government, not teacher-driven, goals is a significant inhibiter.

I can’t reconcile this concern at avoidance as a consequence of “high autonomy” with the observation that “reluctance to engage with controversial aspects…has been a feature of New Zealand education for decades”. I see that problem as the consequence of centralized prescription by groups meeting in seclusion to map out directions subjects would take based on current theories of learning and current interests (always dated by the time prescriptions were filtered through the bureaucracy). These prescriptions strangled subject development, limiting innovation until well past their use-by date when another group were shoulder-tapped to repeat the process. Instead, with “high autonomy” we are seeing practitioner-led innovation, informed by research and consultation with students and the community. Go willingly back to handing responsibility to some closed process? Surveys by the New Zealand History Teachers Association show the majority of current practitioners reject that option.

Currently we are free to choose to explore, adopt and adapt. There are forces that inhibit: options may be constrained by senior managers, Boards of Trustees and communities. There are places in New Zealand where close examination of certain historical events remains contentious and divisive and there could be pressure to avoid or circumvent. I can’t see that centralized prescription will remove such pressure. More pressure comes from the dictates of the competitive funding model in education. Schools have marketing strategies that feature achievement statistics published in the New Zealand Qualification Authority’s “League Tables”. This is where the greatest pressure comes to retain the tried and true as teachers and HODs jumping through appraisal hoops are required to cite pass rates in March to be measured against in February.

Dr Sheehan’s analysis supports prescription in some degree. This is justified by reference to a picture of the teaching community based on evidence gathered in 2010 and 2011, before the realigned standards that allowed access to the freedoms in the New Zealand Curriculum were implemented. I don’t have a national overview of the school history community – and suspect his picture is true for some pockets of practice – but the community I engage with locally and nationally is significantly different than it was five years ago and moving with increasing pace to embrace change. We don’t need codes, check-lists, or requirements for some grand visitation by a centralized agency to supervise. Nor do we need authoritarian intervention to destroy the local initiatives and networks many of us are developing.

We need an empowered community that makes on-going decisions about what their curriculum needs are.

How do we get it?

Firstly, by supporting teachers who are making the effort with forums, PLD, conferences and time and support for them to record, present and share programmes (including recognition of the significance of place and the perspectives added by local stories).

Secondly, Humanities teachers must make common cause to establish the practice of long term planning. Just as politics is hamstrung by the fixation on the election-cycle so educational programmes suffer under the current focus on the ten-month assessment cycle. In History coherent curricular frameworks have been long abandoned to teach a disconnected menu of “past successes”, abandoning structured development of disciplinary knowledge and understandings to seek assessment success. The results are clear: limited engagement (low student numbers), inchoate comprehension of historical concepts and no usable framework of history to take forward. What students need are programmes that establish sequential, deliberate development of skills and knowledge. Schools accept this in Literacy, Numeracy and Science. The Humanities must follow suit, developing 5 and 7 year programmes using backwards planning and developing strong progression indicators.

This requires up-skilling teachers in training and teachers in service. It doesn’t need massive resourcing: the object must be for schools and teachers to become / make their own resources: understanding history by doing it is as vital for teachers as it is for students. Dr. Sheehan notes there is “no shortage of resources” – perhaps, but I believe most are not fit for purpose. They must be accessible in different ways to different levels of students. The best way to do this is to get teachers to do it, applying their classroom experience in collaborative events. Current opt-in-professional learning provision has seen teachers and schools avoid exposure to new approaches – here is where compulsion might actually be of value.

Finally, the role of teachers in developing critical citizens has to be accentuated, especially by politicians and media who currently seize every opportunity to criticize. If there is real commitment to examine and re-assess the past, then leaders should encourage the exploration of “difficult” contexts, supporting programmes that do this and taking to task those that don’t.

The solution lies within the teaching community not in some externally imposed set of requirements that are out-of-date and out-of-touch before we’ve finished reading them.

We need to move away

While much of what Dr Sheehan claims strikes a chord with me as a fellow history teacher, there remain a number of questions that I would like to ask and some generalisations that I sit uneasily around what I perceive to be a worrying call for a mandated/prescribed curriculum.

I was one of the 12 000 who signed the petition calling for commemoration of the NZ Wars and recognise that there is a need to place what happened on our own soil on the same level as the one to which we have elevated our commemoration/remembrance of Gallipoli. However, like Paul Enright, I do not want this to occur in history classrooms under a return to a prescription, instead I want to see teachers encouraged and enabled to explore contexts such as the NZ Wars and be given the appropriate support and PLD to do so. Our focus should be on empowering teachers to initially seek out appropriate local/regional contexts of relevance to them and their community as opposed to forcing a context on them that may or may not be immediate relevance.

While the New Zealand Wars are the only colonial wars in our national history, and by that fact alone are deserving of a place in our programmes and national narrative, we need also acknowledge other wars and conflicts that have just as much significance to other communities, iwi and rohe. The Musket Wars are arguably of greater significance in the South, than the colonial New Zealand Wars of the 1860s, and yet this is ignored or lost, in the national narrative and sadly, the local.

Recently I had the had the privilege, along with several other local history teachers, to be able to visit with local iwi, the one major monument to the Musket Wars in NZ, (Maclean and Phillips (1990) pp17-18), in Mataura, almost as far away from Northland as you can get. This monument stands isolated in a rural paddock surrounded by sheep and hay bales. Gone is the wharenui that was built 80 years ago to remember this battle, gone are the picnic areas that were created so people could enjoy the vista. Instead if one wishes to visit the monument now a climb over fences, and a trek avoiding sheep droppings is required. This forgotten monument is a study in itself of the vagaries of significance and what we do or don’t choose to commemorate. It is a study in the waiting for local schools and at least two I know of have in the last year held field trips to this site and begun the process of building programmes highlighting what occurred there. I know some will be questioning the contention of this particular event, the contention comes in how it is perceived today. In my search to find evidence of who owned the land this memorial sits on, I encountered the view that the Battle for Tuturau was in no way significant, yet in 1934, 83 years ago the community of Mataura felt it was of enough significance to build a monument to remember the centenary of it. Contentious? I believe so. So why bring this up? Because this is our history, the history of the South and what makes this of any less importance, or significance? Why would we foist the New Zealand Wars on schools in the South, when they have their own lost voices to explore and reconnect with?

The conflict with Ngāti Toa beginning in the late 1820s and which was waged up and down the east coast of the South Island through to 1833 is clearly of more direct relevance to this part of Aotearoa. The massacre at Takapuneke is seared into the whakapapa, waiata and haka of Ōnuku and is just as contentious, in this corner of Aotearoa as the New Zealand Wars. The treachery of Pākehā in this massacre is as horrific for Ngāi Tahu on Banks Peninsula, as it is for Waikato and Tainui in Waikato, but I am yet to see a call for these to become part of a national history curriculum. The animosity towards Te Rauaparaha and his actions in the South Island remains to this day. The (in)famous haka, Ka Mete, performed by the All Blacks, is not performed in the South because of the actions of Te Rauparaha, so imagine the reaction from Ngāi Tahu, or any other iwi, should a context be prescribed that does not fit their perspective or iwi history. Contentious? Absolutely. In advocating for the importance of the New Zealand Wars in the kete of knowledge of a modern New Zealander, we must not lose sight of other histories and voices, which in their contexts and rohe are just as important. We must not buy into the idea that one war was of greater importance than another.

Our current fixation on war as the ‘making of our national identity’ also needs to be reviewed. I believe it is unhelpful and we need to move past this. War might have provided a catalyst to us finding our identity but it isn’t the be all and end all. Too many voices and histories are lost in our fixation on war, and its current obsessive focus on Gallipoli. We need to move away from the chronology of battles and troop movements and mind numbing content stuffing that currently passes for historical enquiry and instead focus on the broader context, the involvement of women, Māori, the handling of dissent, the wounded and damaged and the changed society that emerged after 1918. The same is true of the New Zealand wars: focus on campaigns, battles and atrocities and a truer picture may be conveyed, but unless the wars are put in their national and international context and placed in the course of our history their significance will remain shrouded and our opportunities to understand will be limited.

The things have changed since 2011

The statement that contentious issues are not being addressed, is now in 2017 not fair to the many teachers who are actually taking these on. The environment has changed since 2010/11 with realignment of standards and the implementation of the NZC in the senior secondary school. The principle function of this document is to set the direction of students learning and provide guidance for schools (Ministry of Education, p6) where students are at the centre of the teaching and learning allowing teachers the “scope to make interpretations in response to the particular needs, interests and talents of individuals and groups in their classes” (MOE p37) and increasingly teachers are responding to this by ensuring that the contentious nature of aspects of our history are being covered. With trends observed during the 2016 marking period this is mind, I don’t believe that schools do ‘veer away’ from contentious history, nor do they view it as irrelevant. Increasing numbers of teachers want to be involved in clusters devoted to learning about and implementing Māori History and culturally responsive pedagogy. A return to a list of topics from which to build a relevant coherent place based programme of work would be detrimental to this, instead we need to nurture this desire and work with teachers to help develop their understanding of their place and history.

It needs also to be kept in mind that prior to 2011 it was easy to ignore contentious aspects of our history. The prescription and associated examinations did not allow us to explore anything other than what was on the list of approved topics, most of which were Eurocentric, male dominated and aimed at keeping the approved/accepted conventional narratives firmly to the fore. This is not the case now and returning us to a prescription would once again render history courses unable to respond to change and new research until a review conceded some ground.

I am firmly in favour of allowing schools and communities to determine what programmes of work look like in the history classroom. The assertion that communities might not be accepting of contentious aspects of our history is something that I have never experienced. Instead the teachers that I have worked with have had supportive and interested Senior Managers and Boards. A perception is not a problem when there is no reliable evidential basis for it. I would like to see additional research undertaken on this across New Zealand, not just in some the more readily accessible regions.

Alongside this is the need for new research now to ascertain the degree of shift in the history teaching community, and the extent to which New Zealand history is being embedded in the local curriculum, contentious or not. Since 2011 there has been some specific PLD run on programme planning and the Māori History Project implemented to provide teachers with some PLD around local issues. This Project sought to connect history teachers in four rohe across Aotearoa with their local runaka/runanga to develop Māori history components in programmes related to the surrounding area. Place based history and culturally responsive pedagogy have a proven track record in providing context and connection where nationally prescribed courses have failed. A return to a single, centrally mandated prescription would destroy the real networks and progress being made in the schools and communities that are at the forefront of this for what, experience and history tells us, will be minimal gains overall.

Out of this project has come increased engagement of our learners, Māori and Pākehā alike, improved achievement, a greater understanding of their place in their world and an ability to begin to critically evaluate and question new ideas, contexts, or concepts they are faced with. These must be our ultimate, desired outcomes. Does it matter which context our students explore to gain these skills? Does it have to be war? Could it be Māori women and their role in conflict, such as those women who supplied the men in the trenches with arms during the Waikato War? Could it be Māori women and their role in pre1840 Aotearoa, or Māori women and their role as leaders from Te Puea through to Dame Whina Cooper, supporting conscientious objectors to protesting about continued land confiscation? As the mother of two children of Te Rarawa heritage living in the South Island, I want my children to know their iwi history, as well as the history of the rohe which they live in and the national story, warts and all, I do not though want them only exposed to one history, that being the history of the current loudest voice at the table.

References

Author’s Reply

Thank you all for your thoughtful and insightful comments. This is an issue of ongoing concern for all of us who are interested in reconciling the legacy of New Zealand’s colonial past. A process that requires these sorts of conversations as well as a willingness to grapple with the extent to which young people in New Zealand are developing knowledge based understandings of the process of colonisation so that they can engage critically with the challenges we all face in the 21st century. And not just the minority of students who elect to study history as a discipline informed subject. For international readers it is worth noting that although historical thinking about the colonisation experience is emerging as a prominent feature of senior secondary school history programmes, history is only offered as a senior school option. It is not a core subject and in the compulsory curriculum (ages 5-14 years) history is subsumed in the integrated subject of social studies where the extent to which students engage with the difficult and contested features of New Zealand past is variable.

Aata Tirohia te ngaru nui, te ngaru roa, te ngaru paewhenua: By studying and understanding the nature of wave patterns, your decisions will be made appropriately and accordingly.

The commenters are right in that there are risks with all curriculum models. They have drawn my attention to not only examples of innovative history teaching practice (which they are acutely aware of as they are all change agents in the NZ history teaching community) but also to what they see as the problems that would come with returning to a prescribed curriculum model. They have also highlighted the recent Ministry of Education ‘Maori History Project’ that has the potential to inform teachers about the colonial past. In this we are on the same page. I am aware of the innovative features of the history teaching community and how it is shifting its focus (although only a minority of young people ever see the inside of a history classroom).

However, at no stage do I argue for a ‘mandated centralised prescribed curriculum’ shaped by a ‘centralised agency’. In my view it is not either: or. High autonomy/teacher driven or prescribed/mandated. I am not sure what a shift might look like (Harcourt notes perhaps there is a middle way) but rather I am highlighting what I see as the inherent structural problem with a history curriculum in which no content is prescribed when it comes to engaging with difficult and contentious histories. The strengths of the NZ high autonomy model essentially rest on the intellectual confidence of individual teachers and the willingness of the local school community to support them. That is, it is up to teachers and schools. To engage with contested notions about New Zealand’s past is an option. I talk about the implications of this at some length in my latest article. Curriculum choices about history do not occur in a vacuum and teachers do not operate as autonomous entities when it comes to curriculum making. They are embedded in particular school communities and teacher’s curriculum approaches to controversial historical questions will reflect the values, attitudes and collective memories of parents, students and colleagues in their school community. If this fits then there is the potential for innovative teaching, but in many school’s teachers are not sufficiently confident in their knowledge of controversial/difficult features of the colonial past and/or not well supported by their school community to address such questions. In this context the high-autonomy, non-prescriptive curriculum model can work against young people learning about difficult histories. The implications of this debate are important and not only the concern of history teachers (although they have a major contribution to make to this discussion). Rather the knowledge, values and understandings that our young people develop in regards the colonisation experience in their schooling is of concern to everyone in 21st century New Zealand/Aotearoa.

I am grateful for your contribution and I look forward to your comments on my latest article.

———————

Editors’s note: Belated, we’ve received an additional comment by Robert Guyver, unfortunately it has been posted under another article by Mark Sheehan. You find it here: https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/5-2017-2/a-matter-of-choice-biculturalism/#comment-7198