Abstract: Reconciliation? The conservative commentators are at it again. On March 30 this year, The Daily Telegraph attempted to reignite Australia’s “History Wars”.[1] The object of conservative concern was a guide produced by the University of New South Wales that clarified appropriate language use for discussing the history, society, naming, culture, and classifications of Indigenous Australians and Torres Strait Islanders. The newspaper headline, misrepresenting the text of the guide, claimed, “UNSW rewrites the history books to state Cook ‘invaded’ Australia”.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-6055.

Languages: English, Deutsch

Reconciliation? The conservative commentators are at it again. On March 30 this year, The Daily Telegraph attempted to reignite Australia’s “History Wars”.[1] The object of conservative concern was a guide produced by the University of New South Wales that clarified appropriate language use for discussing the history, society, naming, culture, and classifications of Indigenous Australians and Torres Strait Islanders. The newspaper headline, misrepresenting the text of the guide, claimed, “UNSW rewrites the history books to state Cook ‘invaded’ Australia”.[2]

The Struggle for Public Memory

The guide states that “invasion” is a more appropriate term to describe Australia’s past than “settlement”, which was the received and taught history right up until the late 1980s, the period within which many of the most vocal conservative commentators went to school. However, of Captain Cook it simply states that it is more appropriate to say that he “was the first Englishman to map the east coast of ‘New Holland’” than to say he “’discovered’ Australia”[3]. It does make a particular point that the term “discovery” can be offensive. Judging by the airplay given to this issue in the broadcast media, the term “invasion” offends a completely different segment of society. Representations of Australia’s colonial past have been the enduring problem of the history wars.

Perspectives from Both Sides of the Frontier

Historian Henry Reynolds’ groundbreaking The Other Side of the Frontier: Aboriginal Resistance to the European Invasion of Australia (1982)[4] provided one of the first accounts of early European-Indigenous contact from an Aboriginal viewpoint, challenging the received history of a nonviolent frontier. Public awareness of a distinct Aboriginal perspective on Australian history intensified as a result of a series of grassroots protests that culminated in a day of mourning during the bicentennial celebrations of 1988. For many Australians, the call for a day of mourning by Indigenous elders at the time of the bicentennial, televised around the country, was an important catalyst for reflection on the nation’s past, bringing into relief the disjuncture between the official story of peaceful European settlement and Indigenous stories of dispossession, occupation, and oppression.

The High Court’s ruling in the Mabo and Wik land rights cases that followed ensured that the question of an untold Aboriginal history remained in the national psyche. The syllabus documents, released shortly after the bicentennial, registered, for the first time, this perspective from the other side of the frontier, subsequently fuelling a decade-long political struggle over the national narrative. Arguably, the formation of a national History curriculum was a thinly veiled (and largely unsuccessful) attempt by politicians to secure a single story for the nation[5].

Whose Story Do Our Students Tell?

In a recent Australian study[6], pre-service history teachers [n=97] were asked to write for 45 minutes in response to the request to “Tell the history of Australia in your own words”, borrowing a research methodology developed by Canadian Professor Jocelyn Létourneau (2006)[7]. A focus on the colonial past and the poor treatment of Indigenous peoples dominated the narratives. The doctrine of “Terra Nullius”[8], the concept of “invasion”, and a representation of Aboriginal peoples as “inferior” in the eyes of the “White Settlers” were common themes in the stories our future history teachers told. Less than 10% of the narratives discussed Aboriginal resistance to British colonisation, suggesting that, although there was a sense of shame for the dispossession of Indigenous peoples, there was also evidence that the discourse of Aboriginal people as inferior (in this case incapable of successful resistance) had made its mark. Thus, it is clear that the “Black Armband” view of the colonial past is the dominant narrative mobilised by pre-service history teachers, and that texts like the UNSW guide, and state History syllabi since the early 1990s, have had their effect.

How the Left and the Right both get “History” Wrong

I have very little doubt that the early waves of British colonisation were experienced by Australia’s Indigenous peoples as a type of invasion, and that this word serves as an adequate description of their lived experience of colonisation. I have a lot less confidence that this is how the British understood their activities in the Great Southern Land, which seemed to have more to do with securing outposts against other European imperialist powers.

As a historian and history educator, I follow Collingwood[9] here: I believe it is our job to understand not only the “outside” of a historical event (i.e., what happened), but also its “inside” (i.e., why people acted the way they did). If we want to reconcile with our nation’s past, both its traumas and achievements, then we need to face up to the evidence of what happened (avoiding amnesia), and attempt to understand the motivations of people in the past by stepping into their shoes (attempting historical empathy), while being cautious about any intellectual or emotional baggage we are bringing from the present into our interpretations and constructions of the past (remaining cautious of anachronism).

To have historical consciousness is not so much to know the past, as it is to know the prejudices I am bringing to the table in my attempt to understand the past[10]. To do this effectively, I have to understand that history is not the infallible reconstruction of a completely knowable past, but a set of constructed and competing narratives resulting from the application of different historiographic methodologies, different historical questions, etc. If the post-colonial moment is realising that there is more than one narrative of the nation, what is the job of the post-colonial history educator? Surely it is to help students understand that, just as it is possible to have a road map, a weather map, and a topographical map of the same area, it is also possible to respect different narratives of the same past.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Healy, C. (2008). Forgetting Aborigines. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press.

- Parkes, R. J. (2009). Teaching History as historiography: Engaging narrative diversity in the curriculum. International Journal of Historical Teaching, Learning and Research, Vol. 8 No. 2, pp. 118-132.

Web Resources

- Diversity Toolkit – University of New South Wales (UNSW)

https://teaching.unsw.edu.au/indigenous-terminology/homepage (last accessed 14.04.2016). - Why Australia lies to itself about its Indigenous history (Waleed Aly)

http://www.smh.com.au/comment/why-australia-lies-to-itself-about-its-indigenous-history-20160330-gnuo4t.html/homepage (last accessed 14.04.2016).

_________________

[1] Macintyre, S., & Clark, A. (2003). The History Wars. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

[2] Bye, C. (2016). Whitewash: UNSW rewrites the history books to state Cook ‘invaded’ Australia. The Daily Telegraph, March 30, p. 1 & 7.

[3] See the “Diversity Toolkit” in Web Resources above.

[4] Reynolds, H. (1982). The other side of the frontier: Aboriginal resistance to the European invasion of Australia. Ringwood, NSW: Penguin.

[5] Taylor, T. (2009). Howard’s End: a narrative memoir of political contrivance, neoconservative ideology and the Australian history curriculum. Curriculum Journal, 20(4), 317-329.

[6] Remembering Australia’s Past [RAP] Project, HERMES Research Network, The University of Newcastle. Online: http://hermes-history.net/remembering-australias-past-rap/ (last accessed 14.04.2016).

[7] Létourneau, J. (2006). Remembering our past: An examination of the historical memory of young Québécois. In R. Sandwell (Ed.), To the past: History education, public memory, & citizenship in Canada (pp. 70-87). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

[8] See Atwood, B. (2004). The Law of the Land or the Law of the Land?: History, Law and Narrative in a Settler Society. History Compass, Vol. 2 No. 1, pp.1-30; and Fitzmaurice, A. (2007). The genealogy of Terra Nullius. Australian Historical Studies, Vol. 129 No. 1, pp.1-15; to understand the use of this historically problematic concept.

[9] Collingwood, R. G. (1946/1994). The Idea of History (Revised ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[10] Gadamer, H.-G. (1994). Truth and method (J. Weinsheimer & D. G. Marshall, Trans. Second Revised ed.). New York: Continuum.

_____________________

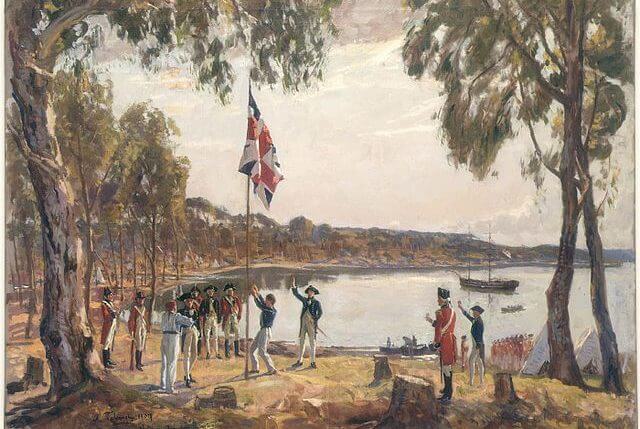

Image Credits

“The Founding of Australia” by Captain Arthur Phillip RN Sydney Cove, 26 January 1788, faithful photographic reproduction of 1937 Oil Painting by Algernon Talmage, picture from Wikimedia Commons, license: public domain (last accessed 17.04.2016).

Recommended Citation

Parkes, Robert: Black or White? Reconciliation on Australia’s Colonial Past. In: Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 16, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-6055.

Aussöhnung? Die konservativen Kommentatoren sind wieder am Werk. Am 30. März dieses Jahres versuchte The Daily Telegraph, die “Geschichtskriege” (History Wars) Australiens wieder zu entfachen.[1] Das Objekt der konservativen Bemühungen war ein Ratgeber der University of New South Wales, der den angemessenen Sprachgebrauch für Diskussionen über Geschichte, Gesellschaft, Namen, Kultur und Klassifizierungen der Ureinwohner Australiens und der Torres Strait Inseln klar stellte. Die Schlagzeile der Zeitung, den Text des Ratgebers missachtend, behauptete, “die UNSW schreibt die Geschichtsbücher neu, um zu konstatieren, dass Cook Australien ‘überfiel'”: “UNSW rewrites the history books to state Cook ‘invaded’ Australia”.[2]

Das Ringen um das öffentliche Gedächtnis

Der Ratgeber sagt, dass sich “Überfall” (invasion) besser als “Besiedlung” (settlement) für die Beschreibung der Vergangenheit Australiens eignet. Das Konzept der “Besiedlung” prägte das historische Lehren und Lernen bis in die späten 80er-Jahre und damit in jener Zeit, in welcher viele der lautstärksten konservativen Kommentatoren zur Schule gingen. Betreffend Kapitän Cook wird allerdings bloss darauf hingewiesen, dass es besser sei zu sagen, dass er „der erste Engländer war, der die Ostküste ‘Neu Hollands’ kartierte, statt zu sagen, dass er Australien ‘entdeckte'”.[3] Der Ratgeber hebt insbesondere hervor, dass der Terminus “Entdeckung” beleidigend sein kann. Nach der Sendezeit zu urteilen, die diese Angelegenheit in den Rundfunkmedien einnimmt, beleidigt das Wort “Überfall” ein ganz anderes Segment der Gesellschaft. Darstellungen der kolonialen Vergangenheit Australiens sind das andauernde Problem der Geschichtskriege.

Perspektiven von beiden Seiten der Grenze

Das bahnbrechende Werk des Historikers Henry Reynolds The Other Side of the Frontier: Aboriginal Resistance to the European Invasion of Australia (1982),[4] eine der ersten Darstellungen der frühen Kontakte zwischen Europäern und Ureinwohnern aus dem Blickwinkel der Aborigines, stellt die tradierte Geschichte einer gewaltfreien Frontier in Frage. Das öffentliche Bewusstsein für eine eigenständige Perspektive der Ureinwohner auf die australische Geschichte wurde durch eine Reihe basisdemokratischer Proteste geschärft, die in einem Tag der Trauer während der Zweihundertjahr-Feierlichkeiten von 1998 gipfelten. Der Ruf der indigenen Ältesten nach einem Trauertag, den das Fernsehen im ganzen Land sendete, wurde für viele AustralierInnen zu einem wichtigen Anstoss, um über die Vergangenheit des Landes nachzudenken.

Der Fokus verschob sich zunehmend auf die Diskrepanz zwischen der offiziellen Geschichte der friedfertigen europäischen Besiedlung und den Geschichten der indigenen Völker über Enteignung, Besetzung und Unterdrückung. Die Entscheidung des Obersten Gerichtshofs in den darauffolgenden Mabo- und Wik-Prozessen zu Landrechten sorgte dafür, dass die Frage einer nichterzählten Geschichte der Ureinwohner in der nationalen Psyche bestehen blieb. Lehrpläne, die kurz nach den Zweihundertjahr-Feierlichkeiten veröffentlicht wurden, hielten diese Perspektive von der anderen Seite der Frontier zum ersten Mal fest. Anschließend heizten sie eine jahrzehntelange politische Debatte über das nationale Narrativ an. Die Entstehung eines nationalen Curriculums für Geschichte war wohl ein schlecht getarnter (und weitgehend erfolgloser) Versuch von PolitikerInnen, an einer einzigen Geschichte für die Nation festzuhalten.[5]

Wessen Geschichte erzählen unsere Studierenden?

In einer kürzlich durchgeführten australischen Studie[6] wurden angehende GeschichtslehrerInnen [n = 97] aufgefordert, innerhalb von 45 Minuten eine Antwort auf die Bitte “Erzähle in eigenen Worten die Geschichte Australiens” zu verfassen, in Anlehnung an eine von der kanadischen Professorin Jocelyn Létourneau entwickelte Forschungsmethode (2006).[7] In den Narrativen dominierte ein Fokus auf die koloniale Vergangenheit und die schlechte Behandlung der indigenen Völker. Häufig vorkommende Themen in den Geschichten unserer zukünftigen GeschichtslehrerInnen waren die Doktrin des „Terra Nullius“,[8] das Konzept des “Überfalls” und eine Darstellung der eingeborenen Völker als “minderwertig” aus der Sicht der “weißen Siedler”. Weniger als 10 Prozent der Narrative behandelten den Widerstand der Aborigines gegen die britische Kolonisierung, was ebenfalls darauf hindeutet, dass trotz Schamgefühlen gegenüber der Enteignung der indigenen Völker der Diskurs über die Ureinwohner als minderwertige Kultur (in diesem Fall unfähig, erfolgreichen Widerstand zu leisten) nachweisliche Spuren hinterlassen hatte. Es ist daher klar, dass die tragische Sicht der kolonialen Vergangenheit das dominante Narrativ ist, das angehende Geschichtslehrende mobilisieren, und dass Texte wie der UNSW Ratgeber oder die staatlichen Geschichtscurricula seit den frühen 90er Jahren Wirkung gezeigt haben.

Wie sowohl die Linke wie die Rechte “Geschichte” falsch verstehen

Ich habe ganz wenig Zweifel, dass die ersten Wellen der britischen Kolonisation von den indigenen Völkern Australiens als eine Art Invasion erlebt wurden und dass dieses Wort ihre gelebte Erfahrung der Kolonisation adäquat beschreibt. Sehr viel unsicherer bin ich hingegen, ob die Briten ihre Aktivitäten in dem Großen Südlichen Land so verstanden haben. In der britischen Sicht hatten diese wohl mehr mit der Absicherung von Vorposten gegenüber anderen europäischen imperialistischen Mächten zu tun.

Als Historiker und Geschichtsdidaktiker folge ich Collingwood[9]: Ich bin davon überzeugt, dass es unsere Aufgabe ist, nicht nur das “Äußere” eines historischen Ereignisses zu verstehen (d.h. was passiert ist), sondern auch das “Innere” (d.h. warum die Menschen sich so verhielten). Wenn wir uns mit der Vergangenheit unseres Landes versöhnen wollen, mit seinen Traumata wie mit seinen Leistungen, dann müssen wir die Beweise für das, was passiert ist, anerkennen (Vermeidung von Amnesie) und versuchen, die Motivationen der damaligen Menschen zu verstehen, in dem wir uns in ihre Situation einfühlen (Versuch der historischen Empathie). Zugleich müssen wir kritisch gegenüber intellektuellen oder emotionalen Haltungen bleiben, die wir aus der Gegenwart in die Interpretation und Konstruktion der Vergangenheit einfügen (Zurückhaltung gegenüber Anachronismen).

Historisches Bewusstsein zu besitzen bedeutet nicht so sehr, die Vergangenheit zu kennen, sondern viel mehr die Vorurteile zu kennen, die ich bei meinem Versuch, die Vergangenheit zu verstehen, auf den Tisch lege.[10] Um hierbei wirkungsvoll zu sein, muss ich verstehen, dass Geschichte nicht die unfehlbare Rekonstruktion einer vollständig erfassbaren Vergangenheit ist, sondern eine Reihe konstruierter und rivalisierender Narrative, die aus der Anwendung von verschiedenen historiographischen Methodologien, unterschiedlichen historischen Fragestellungen usw. resultieren. Wenn das postkoloniale Moment darin besteht, zu erkennen, dass es mehr als ein Narrativ der Nation gibt, was ist dann die Aufgabe der postkolonialen GeschichtsdidaktikerInnen? Sie liegt zweifellos darin, die Studierenden im Verständnis zu unterstützen, dass genauso, wie es möglich ist, für ein und dasselbe Gebiet eine Straßenkarte, eine Wetterkarte und eine topographische Karte zu haben, es auch möglich ist, unterschiedliche Narrative über eine und dieselbe Vergangenheit zu respektieren.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Healy, C. (2008). Forgetting Aborigines. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press.

- Parkes, R. J. (2009). Teaching History as historiography: Engaging narrative diversity in the curriculum. International Journal of Historical Teaching, Learning and Research, Vol. 8 No. 2, pp. 118-132.

Webressourcen

- Diversity Toolkit – University of New South Wales (UNSW)

https://teaching.unsw.edu.au/indigenous-terminology/homepage (letzter Zugriff 14.04.2016). - Why Australia lies to itself about its Indigenous history (Waleed Aly)

http://www.smh.com.au/comment/why-australia-lies-to-itself-about-its-indigenous-history-20160330-gnuo4t.html/homepage (letzter Zugriff 14.04.2016).

_______________________

[1] Macintyre, S., & Clark, A. (2003). The History Wars. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

[2] Bye, C. (2016). Whitewash: UNSW rewrites the history books to state Cook ‘invaded’ Australia. The Daily Telegraph, March 30, S. 1 & 7.

[3] Vgl. “Diversity Toolkit” (unter Webressourcen).

[4] Reynolds, H. (1982). The other side of the frontier: Aboriginal resistance to the European invasion of Australia. Ringwood, NSW: Penguin.

[5] Taylor, T. (2009). Howard’s End: a narrative memoir of political contrivance, neoconservative ideology and the Australian history curriculum. Curriculum Journal, 20(4), S. 317-329.

[6] Remembering Australia’s Past [RAP] Project, HERMES Research Network, The University of Newcastle. Online: http://hermes-history.net/remembering-australias-past-rap/ (Letzter Zugriff 14.4.2016).

[7] Létourneau, J. (2006). Remembering our past: An examination of the historical memory of young Québécois. In R. Sandwell (Ed.), To the past: History education, public memory, & citizenship in Canada (S. 70-87). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

[8] See Atwood, B. (2004). The Law of the Land or the Law of the Land?: History, Law and Narrative in a Settler Society. History Compass, Vol. 2 Nr. 1, S. 1-30; and Fitzmaurice, A. (2007). The genealogy of Terra Nullius. Australian Historical Studies, Vol. 129 Nr. 1, S. 1-15, wo dieses historisch problematische Konzept erläutert wird.

[9] Collingwood, R. G. (1946/1994). The Idea of History (Revised ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[10] Gadamer, H.-G. (1994). Truth and method (J. Weinsheimer & D. G. Marshall, Trans. Second Revised ed.). New York: Continuum.

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

“Die Gründung Australiens” durch Captain Arthur Phillip RN Sydney Cove , 26. Januar 1788. Photographische Reproduktion eines Ölgemäldes von Algernon Talmage, 1937, Bild aus Wikimedia Commons, Lizenz: public domain (Letzter Zugriff 17.04.2016).

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Parkes, Robert: Schwarz und Weiß? Aussöhnung zur kolonialen Vergangenheit Australiens . In: Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 16, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-6055.

Copyright (c) 2016 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 4 (2016) 16

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-6055

Tags: Australia (Australien), Colonial Legacy (Koloniales Erbe), Postcolonial Perspectives, Reconciliation (Aussöhnung)

The work of Robert Parkes in Australian history education research, has not yet, in my opinion, received the attention it is due, at least not here in Australia. Parkes has, for a number of years since the 2007 article ‘Reading history curriculum as postcolonial text: Towards a curricular response to the history wars in Australia and beyond’, and in the 2011 book Interrupting History, been attempting, and largely succeeding, to articulate a curricular response to the postmodern challenge in an Australian history education context.[1] Parkes’ concept of the ‘historiographic gaze’ – the idea of teaching history via historiography wherein multiple narratives might be valid – is a crucial and much needed intervention in Australian history education research. The complexity and contestability inherent in any attempt to teach Australia’s colonial past would certainly be better navigated with the aid of Parkes’ insights.

However, as this article attests, so often the debate over the teaching of Australia’s colonial history involves polarising commentators from both left and right of the political spectrum, and so alienates from the debate the actual history education researchers and practitioners, for whom these competing narratives are indeed a regular challenge.

Nonetheless, I want to suggest that the the role of the post-colonial history educator may demand more than what Parkes suggests; “to help students understand that […] it is also possible to respect different narratives of the same past.” Here I share Kalle Pihlainen’s concern about the evacuation of political commitment stemming from the postmodern agenda. This is not to suggest I am hankering after a naive modernist historiography. Far from it. Rather, I am partial to Pihlainen’s view that via the “universalisation of difference” and proliferation of “innocuous histories”, postmodernism can have, and has had, a depoliticising effect.[2]

I wonder if Parkes’ might respond to this critique, as I doubt post-colonial thinkers would be able to reconcile the idea of the imperialist and racist narrative of Western modernity being merely an alternate, but viable narrative amongst many. Surely this would deny the vital ethico-political dimension of post-colonial thought.

Further, I would add that the work of Roger Simon, the late Canadian educational thinker, might be of value when trying to conceive of a method for teaching contested and traumatic pasts. Simon’s intellectual project, was amongst other things, a persistent attempt to discover the possibilities inherent in a form of studying the past that might cultivate an openness to being “touched by the past” – which was, for Simon, also learning to live in the present ethically, “as though the lives of others matter.”[3] Simon’s method of studying and learning the past was developed over many years with a group of researchers and students at the University of Toronto, and above all was an attempt to learn so that the past might “teach us, face us and challenge us, as something admittedly different than the present and yet as something that deeply concerns us today.”[4] Simon’s work was in a thoroughly post-structural mode, and he was influenced by continental thinkers Walter Benjamin and Emmanuel Levinas. I suspect that Parkes’ idea of the role of the post-colonial educator as the mediator of competing narratives might be enriched and strengthened by an encounter with Simon’s ideas and methods.

That being said, Parkes’ contribution is a welcome contribution from a history education researcher in what is so often a polarised Australian landscape.

References

[1] Robert Parkes, ‘The Historiographic Gaze as a Goal of Pre-Service History Teacher Education?’, History Educators International Research Network Conference, London, 09 Sept 2015.

[2] Kalle Pihlainen, “The End of Oppositional History?”, Rethinking History, 15 (2011): 471.

[3] Roger I. Simon, The Touch of the Past: Remembrance, Learning, and Ethics (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005); Roger I. Simon, Sharon Rosenberg, and Claudia Eppert, eds., Between Hope and Despair: Pedagogy and the Remembrance of Historical Trauma (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2000).

[4] Mario Di Paolantonio, ‘Foreword’, in Roger I. Simon, A Pedagogy of Witnessing: Curatorial Practice and the Pursuit of Social Justice (State University of New York Press, 2014).

The current debate surrounding the terms “settlement” or “invasion” to describe the events that occurred in and around January 26, 1788 when the First Fleet arrived from Portsmouth, England to Port Jackson, Sydney has once again captured the public’s imagination and interest on matters to do with Indigenous and non-Indigenous perspectives on Australian history. This event, being the first colony of Great Britain on the Australian continent was led by Captain Arthur Phillip (who was also given authority as the first Governor of New South Wales), was sent by the British government to set up a colony on the east coast of the continent. In more recent times, the impact of the arrival of the First Fleet on the Australian continent in the year 1788 has been described variously as settlement, colonisation, occupation, or invasion, depending on the perspective of the author; and all four terms have been used at different times in school curriculum.

This latest debate, covered by Parkes, can certainly be seen as another pot shot in the ongoing history/cultural wars that has been either noticeably above the surface, or swimming just below, in discussions around Australia’s national identity and how this history contributes to present views. As a continuing national discourse, there is almost a pathology of its citizens towards describing an understanding of past events as all being positive; there is no room, it seems, in the national psyche for any negativity, much less gross atrocities committed by one group (the coloniser) against another (the colonised). This can be traced in contemporary times to the Prime Ministership of conservative politician, John Howard. Coming into government after a long time in opposition, Howard set about to ensure he established an overtly different view of Australia than his predecessor Paul Keating, a leader with a clear vision for Australia’s future and place in the world, had expressed. Howard held (and likely still does hold) a view of Australian history that seeks to celebrate Australian progressive historical milestones and to marginalise aspects of the nation’s history that seek to profile negative or collective shameful aspects. This approach to history and public memory-making has become known as “the Three Cheers view”[1]. Language used by Howard throughout his prime ministership draws on discourses of ‘common sense’, an attempt to enunciate a common culture amongst Australians, arguably as a way to stifle or limit debate on topics, particularly those connected in some way with the contestation of Australia’s past history; with at its focus the events of 1788 and the subsequent aftermath. Howard is a proud proponent of the positive aspects of Australia’s history, stating: “I believe that the balance sheet of our history is one of heroic achievement and that we have achieved much more as a nation of which we can be proud than of which we should be ashamed”[2].

Although Howard was a proud proponent of the positive aspects of Australia’s; what has transpired is an ongoing confusion about the narrative of Australia’s past particularly one that does not fit within the Whig trope of progressive history. In his contribution, Parkes notes this, writing “representations of Australia’s colonial past have been the enduring problem of the history wars.” The sentiment that exists of the history/culture wars then crosses over to a wide range of other historical events that spark emotion in public and private debates, and where a binary has been created; for example, the ongoing commemoration of Anzac Day. Another enduring problems of the history/culture wars, of which this current issue is an extension of, is the presentism many social commentators bring to historical events and topics. Rather than being approached from an historical perspective, current political contexts cloud opportunities for informed historical debate. In this context, and others like it, binaries can be seen as serving political purposes, and thus are not useful for historical disciplinary thinking. Instead, I argue here, if a world history approach was adopted, one that seeks to extend beyond the confines of a nation’s borders (and the associated jingoism and nationalism that can cloud/hamper decision making), this could be an avenue for History curriculum to investigate topics with rigour and to ensure that students are being equipped with a deeper understanding of the historical events being studied.

In all of this conversation around the use of terms, the current day impact of events that make up part of Australia’s history, on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders cannot be ignored. However, the facts demonstrate that there is still gross inequalities in areas such as education, health, living conditions, and political representation. Indigenous struggles to see the wrongs of the past have not been sufficiently redressed. Unless the general population is taught an Australian history that recognises past injustices and atrocities and Australia at-large can come to agree that it has significant national trauma that still impacts key members of the population, then vicious and polarising debates surrounding terms such as “colonisation”, “settlement”, “occupation”, and “invasion” are set to continue.

References

[1] Blainey, G. (2005). The Black Armband view of history. In M. Fullilove (Ed.), ‘Men and Women of Australia!’: Our greatest modern speeches (pp 30-37). Sydney, Australia: Vintage Books, p. 30.

[2] Howard, J.W. (1996b, November 18). The Liberal tradition: The beliefs and values which guide the federal government. Transcript of The 1996 Sir Robert Menzies Lecture [Online version]. Retrieved from http://menzieslecture.org/1996.html (Last accessed 10/5/2016), n.p.

This debate touches quite a number of aspects of history teaching in post-traditional (Honneth) and plural societies. These have become at least aware that their (post-)modern democratic state (including the acknowledgment of human rights) is by no means the result of their own heroic efforts, but has (also) been accomplished by excluding others from not only the benefits to be gained for themselves but even from the group considered dignified in the first place.

History of modern mankind is ambiguous to say the least. It carries developments and benefits we cannot do without and which are not to be given up, and at the same time one should wish to be able to go back and correct lots of it. But would it be the same then?

Furthermore, the plurality ineluctably connected with modern individualism and mobility (both territorial and social) also makes for a big number of very different experiences and perspectives onto the past.

History wars and debates, as Parkes addresses here, are to a great degree debates around “correct” terminology and concepts — even (or especially) where “identity” is central.

One of the main characteristics of such debates is that all propositions are claims of both a “correct” interpretation and evaluation of the past and of their validity for a greater group – if not all of society. Given the function and relevance of history for identities and most people’s need for sharing an identity with others, this needs not to be lamented, but to be acknowledged.

History education should, however, not let itself into these debates by trying to confirm some and reject other of these identity-narratives (altogether) or by trying to invest students with any kind of “speckless” version to be set against them. It will not work, it will either leave students irritated when confronted with the more emotion-laden version of such narratives or drive them into one of the given positions.

On the other hand, history education should not give in to any kind of relativism. So what should be history education’s answer to such history wars and their less belligerent sisters?

To recognize and address plurality and different narratives on the past is necessary, of course. But it will not be enough. Citizens (and therefore students) need methods and criteria by which to actively and passively take part in these debates without just repeating, prolonging and enforcing them.

One approach and measure therefore should be to both avoid all-encompassing and all-binding interpretations, evaluations and orientations, both explicitly and in terminology, in mandatory texts, and to make them the object of teaching themselves.

History education should aim at developing students’ competencies of historical thinking – both in the sense of abilities and skills, but also in their entitlement and responsibility.

In the specific case, this would mean not to ask whether Australia was “invaded” or “settled”, but to explore what it means in terms of (“factual”) statement, interpretation/conclusion and judgement, to use these terms. So the question should read: “To what extent is it covered by evidence and what does it imply both for our picture of the actors back then and for our different selves today to phrase a statement with the one term or the others(s)?”.

And of course politicians’ and others’ statements about the past need to be scrutinized as to their validity and their claims: What does it really mean to say that a “balance sheet” is in the positive? Students have to (learn to reflect) upon the implications of such a statement: Does it imply a concession of crimes whit it declares unimportant at the same time, because all what counts is the result?

One of the most important insights to be gained from addressing and scrutinizing such different statements on and evaluations of the past could be that if there is no single narrative which covers all interests and perspectives (and there isn’t), it is also not enough to just accept formal plurality, but to work for compatibility of the plural narratives.

Author’s Reply | Replik

Thank you to my colleagues for engaging with this discussion. It is an example of a problem which faces history teachers in many nations around the world, particularly in what we might describe as post-conflict, post-colonial, postmodern, and multi-cultural societies. How do we navigate competing narratives of the “same” past is a question that teachers and students in such societies must face.

The principle underlying my approach to the issue of multiple narratives of the “same” past is identical to that advocated by Andreas Körber, who makes the point above that:

“In the specific case, this would mean not to ask whether Australia was “invaded” or “settled”, but to explore what it means in terms of (“factual”) statement, interpretation/conclusion and judgement, to use these terms.”

In a study of Australian pre-service history teachers’ narratives of the nation, my colleagues and I have found a lack of this type of interrogation. The narratives we have collected from pre-service teachers asked to tell the history of Australia, reveal a tendency to side with the “invasion” side of the debate. Many of my progressive colleagues would applaud this, and see it as the successful outcome of a curriculum committed to telling the truth about Australia’s colonial history. I am more sceptical of this reading. In many of the narratives we’ve analysed, the same pre-service teachers advocated celebratory views of Australia’s involvement in Gallipoli, rehearsing what we might call the “founding mythology” of the Australian nation. A better explanation might be that the pre-service teachers have simply adopted the dominant (politically correct) discourse of both Gallipoli and the colonial past; have not considered how these narratives have come into circulation; and have not considered the fact that their own viewing positions are themselves historically constituted. Thus, what appears to be a politically correct adoption of a truthful vision of the past, “Australia’s colonial history as invasion”, may actually be the evacuation of any sense of the politics of their own perspective, and that of the (public) historians who produced them.

Let me turn then to a much-needed response to Keynes’ astute provocation about the politics of my position. My answer must go somewhat to questions of the purpose of history education.

If the purpose of history education is to teach a true version of the past, then my position would indeed seem apolitical at best. I am certainly aware of Roger Simon’s work, and have explored similar concerns in my early forays into poststructural theory, where I attempted to correct what seemed a naive suggestion in the work of many sociocultural theorists that any encounter with alterity (in this case a narrative that is different to the one you currently hold) would be transformative of one’s own position. Ironically, I felt this position failed to account for the effects of what Wertsch would call the “meditational means” used to make sense of this alternative narrative[1]. I think there is something noble and important in listening to the stories of others (as Simon argues), but I think that exposure to alternative accounts is insufficient to transform individual perspective. Depending on what is mediating an individual’s perspective, it may just harden their commitment to their existing narrative.

It seems to me that when we think about historical narratives, a number of factors mediate their production (and conditions of repetition, circulation, adoption, etc.). In terms of the conditions of production, these relate as Avner Segall has argued[2], to the kinds of questions asked (of the past), the evidence selected, the methods adopted, etc. These, as my interlocutors above have understood, are questions of historiography. By adopting a “historiographic gaze” when we encounter historical narratives, we ask questions about their mode of production. Once we understand their modes of production, we can have a better idea about how trustworthy they are as accounts of the past. But, more importantly, we gain a idea about why some people believe certain things about the past, and others adopt different accounts, irrespective of where the evidence is pointing (or perhaps because of how they interpret the evidence they have selected, based on the bias of their questions). This seems to me not an evacuation of politics, but an ethical project to understand the position of the Other. I would never propose hat an Indigenous person in Australia accept the truth claims of Wig history, and see Australia’s past as peaceful settlement. Nor am I suggesting that “White nationalists” adopt a mournful view of the nation’s past that rejects the “great achievements” of the colonists. I am suggesting that as history teachers our goal should not be to inculcate a particular view of the past at all, but rather, introduce students to the hermeneutic tools they need to understand themselves and others as historical beings, and narratives as historically and methodologically constituted truths.

I am not sure if this means that I see all historical narratives as epistemologically equal, as Seixas suggested in a previous post. I am certainly not saying all narratives are equally true. I am saying that whenever we encounter a narrative, no matter where it was created (the academy, schools, public sphere, etc.), we should try to understand how it was produced, and how our own perspective shapes how we read and interpret it. This seems to me to be the ethical purpose of history education.

References

[1] Wertsch, J. V. (1991). Voices of the mind: A sociocultural approach to mediated action. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

[2] Segall, A. (2006). What’s the purpose of teaching a discipline, anyway? In A. Segall, E. E. Heilman, & C. H. Cherryholmes (Eds.), Social studies – the next generation: Re-searching in the postmodern (pp. 125-139). New York: Peter Lang.