Abstract: How can educators use deep mapping – lived experience of specific environments to cultural practice and histories – in the Humanities and Social Sciences classroom to rethink colonial relationships, settler connections, Indigenous land rights and environmental change? This article outlines a method for introducing deep mapping, in which the student re-reads and recalibrates according to a sensitised multi-perspective where different realities and worldviews, richly overlaid, operate simultaneously.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21034

Languages: English

Deep mapping commands the multi-dimensional consideration of time, place and culture as we navigate the infinite and uniquely patterned layers. Doing so is an approach which can be used when teaching histories and geographies of exploration, invasion, settlement and colonialism. Adapting this process for our students is a way for us to begin to comprehend the effects of colonisation, what ecological degradation looks like, and how we have followed an accelerated trajectory into climate crisis.

Changing the Landscape

During our childhoods in 1980s Perth, Western Australia, it was commonplace to catch fish, starfish, prawns and crabs on the river, and families gathered on the banks of the Derbarl Yerrigan around fires with prawning nets or fishing rigs.[1] By the mid-1990s, after troubling mass death of fish and excessive algal blooms partly caused by fertiliser (nitrate) run-off from agricultural areas inland, these were things of the past. The rush to change this ancient landscape into an industrialised modern state – grasping at abundant resources and resenting the absence of others – irreversibly and catastrophically altered the landscape and waterways.

The rapidity and the scale of the changes in the Perth sandy basin in Western Australia is not dissimilar to the industrial and post-industrial reshaping and environmental damage almost every modernised place on earth has undergone. Yet, viewed from our perspective it seems extraordinary that a rapid change has taken place on ancient country, the boodja of the Whadjuk Noongar people.

How do we critically engage with and begin to comprehend these scales of change in a classroom? Capture the cultural as well as environmental change and degradation, to raise questions about what might be if the speculative lens shifts? Further to this, how was it instituted in the first place? And why do we keep returning to it? Is it in the mapping?

The purpose of this article is to explore how we can use deep mapping – lived experience of specific environments to cultural practise and histories – in the Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS) classroom to rethink exploration, colonial relationships, Indigenous land rights and environmental change. We outline a method for initiating the reorientation of deep mapping, in which the observer re-reads and recalibrates according to a sensitised multi-perspective where different realities and worldviews, richly overlaid, operate simultaneously.

Deep Mapping

Deep mapping is a multidisciplinary approach to place that conveys a vitally different experience of location. To deep map is to focus in depth on specific sites and regions and to pay “attention to the patina of place.”[2] The act of deep mapping invokes the “ambiguous, the haptic, the opaque, the embodied, the in-between”[3]: the crucial connection between lived experience of specific environments to cultural practice and histories in moving, sinuous strands.

Deep mapping seeks the meshwork that binds place and inhabitation, the flow of space-time between material phenomena and vestigial and often amorphous traces of human and nonhuman habitation.[4] It links past and present as a palimpsest or embedded way, interpreting “the historical and the contemporary, the political and poetic, the factual and fictional, the discursive and the sensual”.[5] Thus deep mapping is the space where representations of space cross with intellectual journeys and aesthetic engagements, including the traditional, mythic, literary, folkloric, historical, geographical, environmental and scientific. In this sense, stories of different cultures, times and world-views co-exist, but in separate, non-hierarchical relation.

While deep maps “reference the tangible and material they include discursive and ideological dimensions […] topographical and relational, revealing ties that places have with others and revealing their embeddedness.”[6] To take stock of the rapid change that has occurred on ancient and stolen land, we must understand the embeddedness. Samia Khatun’s Australianama used linguistic perspective to reimagine the ‘origin’ map of Australia and to reverse the “discursive erasure of Aboriginal peoples and their geographical imaginations – an erasure which is foundational to settler mentality.”[7] Khatun argued that the mono nature of Australian colonial society has limited how we read, hear, feel and write history, and by adopting a pluri-cultural approach she raised the question of how we restore Indigenous geographies.[8]

The Site: The ‘Zwaan’ River

The site for our practice of deep mapping is the Derbarl Yerrigan / Swan river, a historical, geographical and cultural entity; in place but moving.[9] The Swan coastal plan has Noongar artefacts dating 40 to 60 000 years. They are custodians of the oldest living culture in the world, a culture driven in different places and ways to the brink of dissolution through the violent actions of generations of explorers and colonisers. Above all other differences, they had weaponry and force of numbers, the likes of which were absent from Indigenous story or experience. These patterns repeat an echo in varied forms across the globe, particularly with the advances in technologies from the late 1400s onwards. These advances brought about the Age of Sail, and so Indigenous Australians encountered European seafarers – whalers, sealers, explorers, pirates, explorers, colonists.

One such exploration, the Voyage aux Terre Australes, sailed out of Le Havre on 19 October 1800 commanded by Nicolas Baudin and Jacques Félix Emmanuel Hamelin. The plan was to follow the path of Captain James Cook’s third voyage and complete it by exploring and mapping the south west of New Holland while undertaking observation and research relating to Geography and Natural History. They were instructed: the ‘Zwaan River’ demands to be investigated’.[10]

When the Géographe arrived at the mouth of the Zwaan in mid-June 1801 ahead of the Naturaliste, Sub-lieutenant Heirisson took longboat to chart the river and collect specimens (Hamelin Journal). Once on the river they sailed through the pelicans, swans and jellyfish and reported on the many new plants they saw and smelled. Heirisson charted their journey continuously taking soundings by dropping a lead line with tallow in the base. The sticky tallow attracted sediment, shells and sand, indicating the flow and the depth, and the lead weight disrupted and dislodged all that lay in its path as the line was thrown and retracted. After five days the longboat returned with items collected and what was declared as the first known map of the rivière des Cygnes.

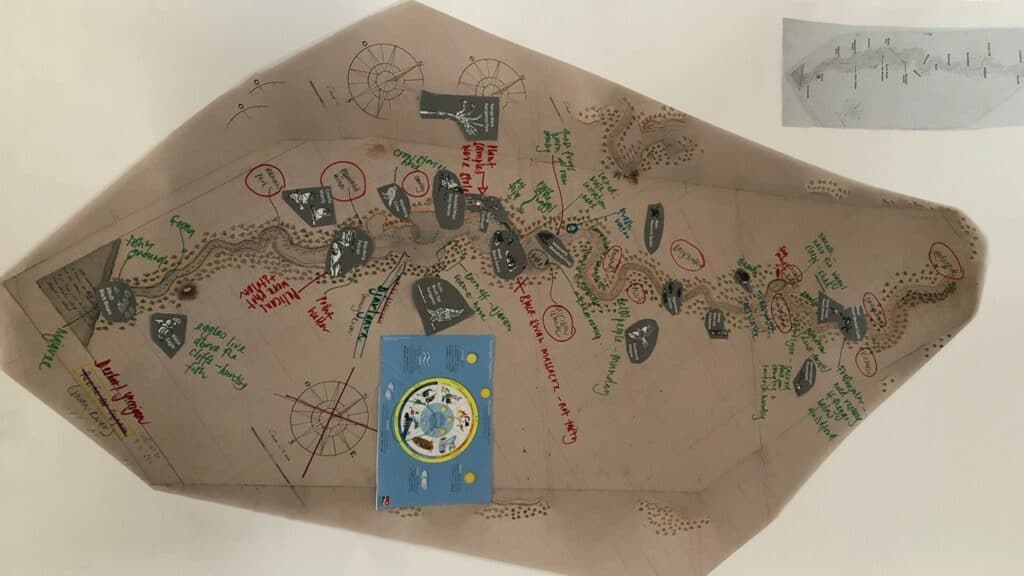

Fig 1. Deep Mapping in the HASS classroom exercise. Image credit: Samantha Owen

In the HASS classroom

Using the story of the Heirisson map of the Derbarl Yerrigan as a case study, we developed an activity which could be adapted for the school and university HASS classroom. Our test site was a group of 9-10 year olds. The Western Australian Year 4 HASS curriculum covers Exploration, First Contacts, how First Nations people adapted their ways of living after colonisation, and Sustainability.[11] The students were using the river and learning about rivers as the major landform to guide their learning. Samantha Owen took to the group the story of the Heirisson expedition,[12] a number of A1 size reproductions of the map the explorers produced to be used for group work,[13] a Whadjuk Noongar language guide for plants, animals and landforms in the local area, a guide to the Whadjuk Noongar seasons, images of plants and animals local to the area, and an Indigenous history of the area.[14]

Connection to the River

The first task was to find out how the children connected to the river. In groups they clustered around the map and marked places that they went swimming, fishing, picnicking, sailing along the long snake-like shape. They began to notice that the map they were using did not look like the one they usually saw. At this point we introduced the Heirisson map and told the story of the expedition. In telling the story we worked to have empathy for the explorers traversing an unknown river, eventually scared from the river as they were terrorised by the wildlife. Sitting in the rain in the longboat they prepared to go ashore and all at once: “we heard a terrible noise that filled us with terror; it was something like a roaring of a bull, but much louder, and seemed to come from the reeds close to us. At this formidable sound we lost all desire to go ashore.”[15]

As a group, we wondered if as well as fear they could sense that their presence was possibly unwelcome. We also consulted our sources and by reading the Indigenous history we found that very close to the mooring was Kooyamulyup, the place of the frogs and a place of initiation for young men. We listened to the frog sound and we wondered: was the noise was a frog chorus greeting the Makuru rain or a bittern making a feeding call for frogs.[16] We took instances like these and mapped them, putting in the story of the Waugal and the birth of the river. We brought together stories of exploration, Whadjuk Noongar people, migrants and the children in the classroom.

Working with the class, together we wove the stories and the languages to think about the change brought about by colonisation, the stress to our eco-system and what we might do to respect these stories and our environment. The mapping enriched our understanding and also provided an approach to deal with contested histories in a non-confrontational way which asked those participating to reflect on their own understandings and practices.

We have suggested that deep mapping is an effective strategy for recognising the multi-dimensionality of time, place and culture. Deep mapping can be used in the classroom when teaching histories and geographies of exploration, invasion, settlement and colonialism and it also provides a method to approach environmental change and to trace the accelerated trajectory to crisis.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Jones, Jo and Curtis, Neil, eds. Four Rivers: Deep Maps, Perth: University of Western Australia Press, 2022.

- Khatun, Samia, Australianama: The South Asian Odyssey in Australia, New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Banivanua Mar, Tracey and Edmunds, Penny, eds, Making Settler Colonial Space Perspectives on Race, Place and Identity, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Web Resources

- Perera, Suvendrini and Pugliese Joseph et al. “Deathscapes: Mapping Race and Violence in Settler States”: https://www.deathscapes.org/ (last accessed 21 October 2022).

- Rachel Perkins, The Australia Wars (series): https://www.sbs.com.au/ondemand/tv-series/the-australian-wars (last accessed 21 October 2022).

- Ryan, Lyndal et al. “Colonial Frontiers Massacre Map.”: https://c21ch.newcastle.edu.au/colonialmassacres/map.php (last accessed 21 October 2022).

_____________________

[1] See also David Ritter, “The Man Without a Face,” Griffith Review: Looking West, 47, January 2015:

[2] Mike Pearson and Michael Shanks, Theatre/Archaeology (New York: Routledge, 2005), 54.

[3] Iain Biggs, ‘Deep mapping as an essaying of place’ [illustrated talk], Bartlett School of Architecture, London: University College London, 9 July 2010: http://www.iainbiggs.co.uk/text-deep-mapping-as-an-essaying-of-place/ (last accessed 21 October 2022).

[4] Tim Ingold, Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description (London: Routledge, 2011).

[5] Pearson and Shanks, Theatre/Archaeology, 64–65.

[6] David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan and Trevor M. Harris, eds, Deep maps and spatial narratives (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015) 4.

[7] Samia Khatun, Australianama: The South Asian Odyssey in Australia (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018) 19.

[8] Khatun, Australianama, p. 93.

[9] Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

[10] Comte de Fleurieu, ‘Plan of Itinerary for Citizen Baudin’, in Baudin, Nicholas, The journal of post Captain Nicolas Baudin, Commander-in-Chief of the corvettes Geographe and Naturaliste, assigned by order of the Government to a voyage of discovery. [1800-1803], (trans) C. Cornell, Christine. Libraries Board of S. Aust, Adelaide, 1974, pp. x–xii. p. 3.

[11] School Curriculum and Standards Authority. Humanities and Social Sciences Curriculum – Pre-Primary to Year 10, 2017: https://k10outline.scsa.wa.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/364554/Humanities-and-Social-Sciences-Curriculum-Pre-primary-to-Year-10.PDF (last accessed 21 October 2022).

[12] Samantha Owen, “A Tale of Black Beaks: Naturaliste Explorers Encounter the Derbarl Yerrigan”, in Jones, Jo and Curtis, Neil, eds. Four Rivers: Deep Maps (Perth: University of Western Australia Press, 2022), 131-149.

[13] François-Antoine Boniface Heirisson, Chart of the Swan River, 1801. The Freycinet Collection, State Library of Western Australia, Call Number MN 2146 / slwa_b2112066_30: https://webarchive.slwa.wa.gov.au/freycinet/swan-river-map (last accessed 21 October 2022).

[14] Debra Hughes-Hallett, Debra. Indigenous history of the Swan and Canning rivers, Perth: Swan River Trust, 2010: https://www.noongarculture.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/indigenous-history-of-the-swan-and-canning-rivers.pdf (last accessed 21 October 2022); Darcy Ranking and Cassie Lynch, Connecting to Our Rivers: Kambarang Poster (available on request).

[15] François Péron (continued by Louis de Freycinet), A voyage of discovery to the southern lands, Vol I. second edition 1824. Books I to III, comprising chapters I to XXI, (trans) C. Cornell (Adelaide: Friends of the State Library South Australia Inc., 2016), 145.

[16] Frank Horner, The French reconnaissance: Baudin in Australia 1801–1803, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1987, p. 172; Leslie. R. Marchant, France Australe (Paris: Editions France-Empire, 1998), 165.

_____________________

Image Credits

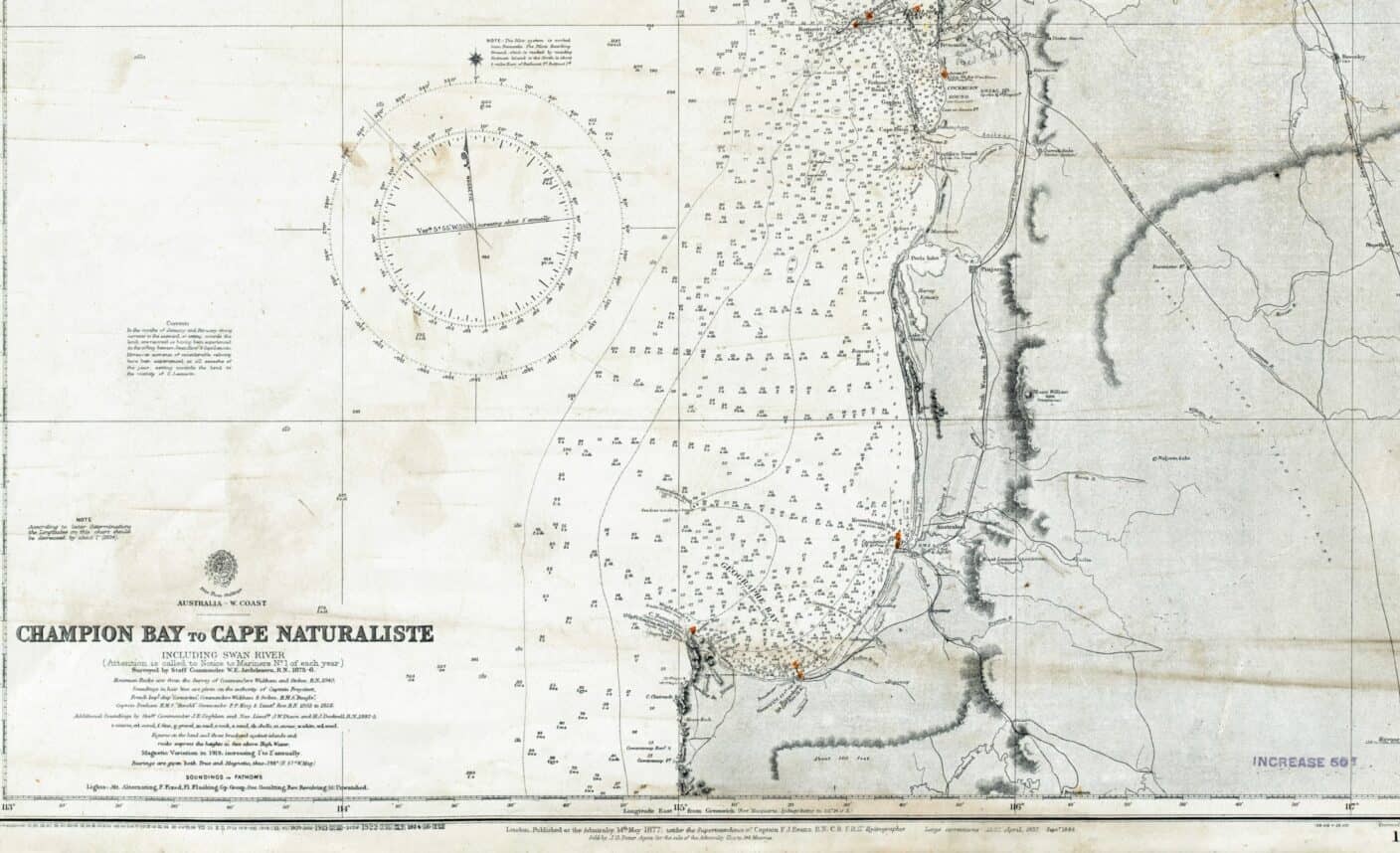

Nautical chart of the west coast of Australia from Champion Bay to Cape Naturaliste including Swan River © 1877 F.J. Evans, Public Domain via Commons.

Fig 1. Deep Mapping in the HASS classroom exercise. © 2022 Samantha Owen.

Recommended Citation

Owen, Samantha, Jo Jones: The Place of Deep Mapping in Teaching. In: Public History Weekly 11 (2023) 1, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21034.

Editorial Responsibility

Copyright © 2023 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 11 (2023) 1

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21034

Tags: Australia (Australien), Deep Mapping, Environment (Umwelt), Geography teaching, History Didactics (Geschichtsdidaktik), Indigenous Peoples (Indigene Völker)

To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

OPEN PEER REVIEW

Challenging Educators

This thought provoking and practical article challenges educators to reorient their understanding and practice regarding the role of deep mapping in Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS). That is, to promote authentic learning environments, where students are challenged to read, re-read and recalibrate, thereby developing understandings of multiple perspectives “where different realities and worldviews, richly overlaid, operate simultaneously.” Developing such skills is central to deeper learning of histories and promoting social cohesion through social and citizenship education amongst community members.

As presented in the case study, students aged 9-10 years were engaged in deep mapping that drew upon their prior knowledge and contextual experiences of the Derbarl Yerrigan. This facilitated the opportunity to deeply engage in an exploration of “how First Nations people adapted their ways of living after colonisation and sustainability” and to promote thinking about multiple perspectives and realities. It is well documented that when learning connects directly to learner’s lived experiences and environment, learning is made meaningful and enjoyable, potentially leading to enhancing engagement and academic achievements.[1] “All learners have rich histories and curiosity about their world which equips them with a culturally informed platform from which to continue to develop and learn”.[2] Within this case study, the Heirisson map was used to spark student’s curiosity about the way the map differed to what they were used to. This provided an excellent way to commence the planned inquiry by embracing all learners, their capabilities, communities and life-worlds, thereby enabling them to be visible in the curriculum.[2][3]

In many HaSS subjects an element of ethical inquiry is naturally embedded. That is, elements of initiating a community of inquiry approach were evidenced in the deep mapping of this case study challenging students to extend learning about colonisation, sustainability and multiple perspectives.[4] This pedagogical approach, underpinned by the work of Pierce, Dewey and Vygotsky, provides a vehicle to explore ethical issues through guided dialogue that takes place as part of a shared inquiry.[5] Through dialogue, the community of inquiry moves from a shared understanding of a stimulus, in this case the student’s use of the Derbarl Yerrigan, to a “deeper understanding of the truth of the idea(s) being explored”.[5] It is in this way that the educator, as facilitator, provides opportunities for learners to test, justify and contest their ideas and those of their peers. There is no need to reach a consensus as the aim is to enable students to explore and challenge their own beliefs while gaining insights into the topic under exploration and respect multiple perspectives and orientations.

A community of inquiry commences with a question that every learner can answer. With the case study presented, learners had already begun to engage in discussions about how they use and engage with the Derbarl Yerrigan; something they were all able to relate to. From this they recognised that the Heirisson map differed from what they were familiar with, so naturally questions emerged which could be used to underpin and shape a community of inquiry to further complement and enrich the learning. For instance, questions about the explorer’s travels and the ethics of the way that Australia’s First Nation peoples were treated could be raised leading to understanding and empathy.

Our learners are surrounded with complex ethical issues as they engage with places and spaces. This article has thereby provided a rich insight into the multidisciplinary approach of deep mapping of specific places and spaces that challenges the exploration of the intersectionality of a myriad of elements, including cultural practices, histories, languages, literary stories, experiences, geography, environments, sciences, different times, and worldviews that encourage students to explore beyond their understandings to respect multiple perspectives and histories that are not hierarchical. Facilitating such curiosity can inform developing a shared community of inquiry that provides a safe space in which to develop lifelong skills while also learning about issues such as colonisation and sustainability. There are a large number of resources that educators can use to support them in employing these approaches and we would encourage you to explore them next time you are planning your HaSS units of work.

_____

[1] Price, D., Green, D., Memon, N., & Chown, D. (2020). Richness of complexity within diversity: educational engagement and achievement of diverse learners through culturally responsive pedagogies, The Social Educator, 38(1), 42-53.

[2] Price, D. & Green, D. (2019). Inclusive approaches to social and citizenship education, The Social Educator, 37(2), 29-39.

[3] Price, D., & Green, D. (2019). Humanities and Social Science for Everyone: Inclusive approaches respectful of learner diversity (Chapter 22). In D. Green & D. Price (Eds.), Making Humanities and Social Science Come Alive. Cambridge.

[4] Lipman, M. (2003). Thinking in education. Cambridge University Press.

[5] Mills-Bayne, M (2019). Engaging with ethical understanding in the early years and beyond: The community of inquiry. In D. Green & D. Price (Eds.) Making Humanities and Social Sciences Come Alive. Cambridge University Press.