Abstract: School subjects suffer from a constant state of lack: at the same time that one demands a response to the future from them, their very nature makes it impossible for them to advance at the pace of the present. However, there are junctures that oblige them to give an immediate response. This is the case of the current relationship between Mexico and the United States. It is an extremely broad topic, so I will solely reflect on the nation’s history curriculum. What interpretations of Mexico-United States relations will the new curriculum of Mexican history recommend? What should we study to prepare a critical citizenry?

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-9124.

Languages: Español, English, Deutsch

Las asignaturas escolares viven en constante estado de falta: al mismo tiempo que se les exige responder al futuro, su naturaleza les imposibilita ir al ritmo del presente. Sin embargo hay coyunturas que las obligan a responder de manera inmediata. Este es el caso de la relación actual entre México y Estados Unidos. Es un tema muy amplio, por lo que sólo reflexionaré sobre el currículum nacional de historia. Qué interpretaciones sobre las relaciones México-Estados Unidos prescribirá el nuevo currículum de historia mexicano? Qué debemos estudiar para fomentar la ciudadanía crítica?

México-Estados Unidos

Es imposible resumir las complejas relaciones de México con los Estados Unidos. Sin embargo, hay que señalar dos puntos relevantes para la enseñanza de la historia.[1] El primero de ellos es que para México, desde el primer día de su independencia (1821), la frontera con Estados Unidos ha estado presente. Baste mencionar como causa nodal al expansionismo norteamericano, la invasión a México por Estados Unidos en 1847 y la pérdida de más de la mitad del territorio. A esto siguieron nuevas intervenciones e injerencias de todo tipo, incluida la maquinación de un golpe de estado en 1913. Los hechos históricos dieron a la política mexicana una impronta antinorteamericana, posición que con el Tratado de Libre Comercio (TLC) desapareció de la casta política. Estas relaciones han sido ampliamente dominadas por Estados Unidos.

El segundo es que la relación es multidimensional. Se da en niveles y dimensiones muy variadas: políticos y grandes capitales, migrantes, crimen organizado, cooperación científica, evangelizaciones, turismo, amores y una americanización de ciertas partes de la cultura mexicana. El resultado histórico es un sentimiento por demás paradójico: amor desenfrenado hacia lo norteamericano y odio mortal hacia lo gringo. Sea cual sea la posición que se tome, es incuestionable que Estados Unidos es parte constitutiva de nuestra plural identidad.[2]

Estados Unidos en el currículum mexicano

México se encuentra en plena reforma curricular. Una de sus ramas es la asignatura de historia. Se supone que los nuevos contenidos serán publicados próximamente. A pesar de ser un asunto público, nadie sabe nada. Por diversas razones, cabe especular que los programas de historia serán diseñados por uno o dos historiadores que darán especial importancia a su identidad profesional y al uso de fuentes primarias en el aula. No creo que modifiquen el nacionalismo mexicano y la relación de Estados Unidos quedará soslayada, a pesar de la violencia de Trump. Por tanto, de acuerdo a la temporalidad de las asignaturas escolares, el programa mantendrá la visión integracionista del TLC y no será capaz de responder a la coyuntura actual, imaginando un futuro sin depender de Estados Unidos.

Lo que llamo integracionismo[3] y contra lo que Trump alinea sus baterías, radica en el diseño de México como parte estructurante de la economía norteamericana. En esta lógica Estados Unidos ha sido enseñado en las escuelas como un socio comercial. Para eso, el programa vigente ve a Estados Unidos simplemente como vecino y en el caso del siglo XIX, como un vecino en expansión. Una muestra del cambio histórico, es que en los años setenta se denominaba intervención norteamericana de 1847, y no guerra, como se usa en Estados Unidos y hoy en México.[4] Otros acontecimientos que se prescriben son la independencia de las trece colonias, la presencia de Estados Unidos en la posguerra y la lucha por los derechos civiles de los afroamericanos. El libro de texto de historia contemporánea de México, único, gratuito y obligatorio, no cambia las versiones en lo sustantivo.[5] Por ejemplo, las causas del conflicto 1846-1848 reproducen la visión estadounidense: como México no vendió tierras se vieron obligados a conseguirlo militarmente.[6] Esto es ejemplo de por qué Peña Nieto se sorprende por las groserías de Trump: México replanteó la interpretación del pasado nacional para abandonar la identidad latinoamericana y ser parte de Norteamérica, lo que modificó la mirada de México hacia Estados Unidos. Pero lo que no logró el neoliberalismo mexicano, es alterar la mirada norteamericana sobre México.

Ciudadanía, futuro y Trump

Una diferencia entre historiografía y enseñanza de la historia es que la primera sabe que es muy incierto hacer prospectiva a partir del pasado y la otra sabe que sólo existe en cuanto delinea un futuro. Aquí, me veo enfrentado a una combinación entre las dos. Mi cálculo es el siguiente: el nuevo programa de historia trabajará colateralmente la relación México-Estados Unidos. Como mucho, se promoverá una idea edulcorada de intercambio binacional. Su intención será ocultar en las aulas las tensiones –y el temor- que produce Trump. A esto hay que agregar la lógica de formación ciudadana que, según se puede ver en el Modelo Educativo 2016,[7] dará continuidad a la formación valoral por sobre la formación política. Esto implica que en vez de enseñar la relaciones de poder entre ambos países, el racismo antimexicano, la desigualdad que expulsan a millones de trabajadores mexicanos hacia Estados Unidos o los derechos sociales atacados por el TLC, se promoverán los conceptos de respeto o tolerancia.

En cambio, una visión alternativa exige que el modelo educativo parta de una visión de ciudadanía crítica. Esto implica ver la relación México-Estados Unidos desde su perspectiva multidimensional. Se trata de analizar en las aulas las condiciones de subordinación –y en muchos casos de resistencia- en la que hemos vivido por doscientos años, pero también comprender las infinitas maneras de relacionarse entre los ciudadanos de ambos países por fuera de las instituciones del Estado, es decir, comprender también las formas de interacción positiva que se han dado entre los mexicanos y los estadounidense de a pie… o por lo menos, con aquellos que no votaron por Trump.

_____________________

Bibliografía

- Terrazas y Basante, María Marcela, Gerardo Gurza Lavalle, Paolo Riguzzi, and Patricia de los Ríos, Las relaciones México-Estados Unidos: 1756–2010. Mexico City: UNAM, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, 2012.

- Josefina Zoraida, and Lorenzo Meyer, México frente a Estados Unidos: (un ensayo histórico 1776–1988). Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1982.

Vínculos externos

- Comisión Nacional de Libros de Texto Gratuitos. SEP: Historia. Quinto Grado. Mexico 2016:

http://libros.conaliteg.gob.mx/content/common/consulta-libros-gb/index.jsf?busqueda=true&nivelEscolar=5&grado=8&materia=45&editorial=&tipo=&clave=&titulo=&autor=&key=key-5-8-45 (último acceso 12.04.2017). - Red Magisterial, Planeación Interactiva de educación básica: https://www.redmagisterial.com/planea/secundaria/9-3er/1567-historia/20/ (último acceso 12.04.2017).

- Museo Nacional de las Intervenciones: http://sic.conaculta.gob.mx/ficha.php?table=museo&table_id=978 (último acceso 12.04.2017).

_____________________

[1] Un texto fundamental para entender las relaciones entre México y Estados Unidos desde la historiografía contemporánea mexicana es Terrazas y Basante, María Marcela, Gerardo Gurza Lavalle, Paolo Riguzzi, y Patricia de los Ríos. 2012. Las relaciones México-Estados Unidos: 1756-2010. México: UNAM, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas. Asimismo las amplias investigaciones de Lorenzo Meyer son indispensables, y en especial: Josefina Zoraida, y Lorenzo Meyer. 1982. México frente a Estados Unidos: (un ensayo histórico 1776-1988). México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. Un resumen desde una posición más próxima al integracionismo puede verse Velásquez Flores, Rafael. 2011. “La política exterior de Estados Unidos hacia México bajo la administración de Barack Obama: cambios y continuidades”. Norteamérica. No. 2. Julio-diciembre.

[2] Esto puede verse con facilidad en el nombre oficial de México: Estados Unidos Mexicanos.

[3] Un ejemplo de este integracionismo se pudo ver con el movimiento y la marcha del 12 de febrero de 2017 denominada #vibraméxico. Este movimiento que aglutinó a sectores del gran capital e intelectuales de corte liberal, es decir, a los sectores que promovieron y se han beneficiado ampliamente con el TLC. Este grupo se manifestó en contra de Trump y exigió mayor firmeza al gobierno de Peña Nieto hacia la política norteamericana. El fenómeno fue interesante, pues al mismo tiempo que defendían una integración total con Estados Unidos, promovieron un nacionalismo ramplón y muy excluyente, en el que todo aquel que no defendiera sus intereses no era patriótico. Lo que no vieron es que la amenazas de Trump al libre comercio no le importan a la mayoría de los mexicanos, pues no han sido beneficiados por el tratado. Por el contrario, son victimas de la profunda desigualdad que impera en México. Lo que si les preocupa a los sectores populares es, sin duda, la situación de la migración y de los millones de parientes que tienen viviendo y trabajando en Estados Unidos.

[4] Esta forma higiénica de interpretar la intervención, invasión o guerra de Estados Unidos contra México, no es exclusiva de la educación obligatoria, es también un fenómeno historiográfico. Si se compara la interpretación de Vásquez y Meyer de 1982 y de Terrazas y Gurza de 2012, se puede distinguir como en los primeros predomina la idea de intervención o invasión, es decir, un poderoso que ataca a otra nación, mientras que en los segundos predomina la idea de guerra, es decir, el enfrentamiento entre iguales pero en relación asimétrica.

[5] En el libro de texto de quinto de primaria dedicado a la historia de México independiente, Estados Unidos tiene una presencia significativa: aparece como tal 59 veces, más varias como gobierno o cultura estadounidense (15) y otras tantas como norteamericanos (5). Entre los acontecimientos históricos mencionados se encuentran que Estados Unidos fue una de las primeras naciones en reconocer la independencia de México, la guerra 1846-1848, las presiones norteamericanas para la salida del ejército de Napoleón III de México, las inversiones norteamericanas, la intervención del embajador en el golpe de estado de 1913, las relaciones conflictivas de la posrevolución, el programa bracero durante la segunda guerra mundial, la migración hacia Estados Unidos y por supuesto el TLC. Por lo general, el tono del libro es cordial hacia el vecino del norte.

[6] El texto de Howard Zin tiene una posición mucho más crítica sobre la intervención norteamericana que el propio gobierno mexicano actual. Zinn, Howard. 2006. La otra historia de Estados Unidos desde 1492 hasta hoy. México: Siglo XXI.

[7]Una discusión de la formación ciudadana en el Modelos Educativo 2016 desde una perspectiva crítica, podrá verse en Plá, Sebastián (en prensa) “La despolitización del ciudadano. Crítica al Modelo Educativo 2016 desde la pedagogía por la justicia social”. Alba, Alicia de y Ducoing, Patricia. Educación Básica y Reforma Educativa. México. UNAM. Instituto de Investigaciones sobre la Universidad y la Educación.

_____________________

Créditos de imagen

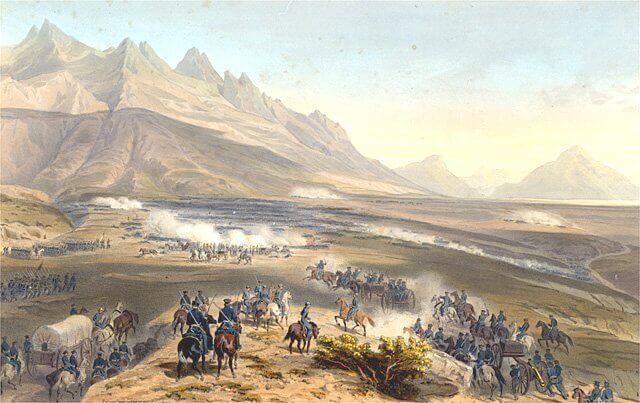

Battle of Buena Vista during the Mexican-American War, painting by Carl Nebel 1851; @ wikimedia

Citar como

Plá, Sebastián: La enseñanza de la historia en tiempos de Tump. In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 15, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-9124.

School subjects suffer from a constant state of lack: at the same time that one demands a response to the future from them, their very nature makes it impossible for them to advance at the pace of the present. However, there are junctures that oblige them to give an immediate response. This is the case of the current relationship between Mexico and the United States. It is an extremely broad topic, so I will solely reflect on the nation’s history curriculum. What interpretations of Mexico-United States relations will the new curriculum of Mexican history recommend? What should we study to prepare a critical citizenry?

Mexico – United States

It is impossible to sum up the complex relations of Mexico and the United States. Nevertheless, two key points for history education should be highlighted.[1] The first of them has existed from the first day of Mexican independence (1821), namely the border with the United States. We need only to mention it as a key cause of American expansionism, the invasion of Mexico by the United States in 1847 and the loss of more than half of the country’s territory. This was followed by subsequent interventions and various sorts of interference, including the 1913 coup plot. The historical events gave Mexican politics an anti-U.S. streak, a position that disappeared from the political class with the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). These relations have largely been dominated by the United States.

The second is that the relationship is multidimensional. It occurs at a wide range of levels and dimensions: politics and transnational companies, migrants, organized crime, scientific cooperation, proselytization, tourism, love, and an Americanization of certain parts of Mexican culture. The historical result is an extremely paradoxical sentiment: unbridled love for the American and mortal hatred of the gringo. Whatever stance is taken, the United States is an unquestionably constituent part of our plural identity.[2]

The United States in the Mexican Curriculum

Mexico is currently in the midst of curricular reform. One of the reform branches is history courses. Publication of the new content is presumably forthcoming. Despite the fact it is a public matter, no one knows anything about it. For various reasons, it is worth speculating that history programs probably will be designed by one or two historians who will give special importance to their professional identity and the use of primary sources in the classroom. I think that Mexican nationalism will not be substantially modified and that the relationship with the United States will be avoided, despite Trump’s violent rhetoric. Therefore, given the temporality of school courses, the program will preserve the integrationist vision of NAFTA and, thus, will be unable to respond to the current situation, imagining a future without depending on the United States.

What I refer to as integrationism,[3] in contrast to Trump’s lines of attack formulation, resides in the design of Mexico as a structural part of the American economy. In this conciliatory logic, the United States has been taught in schools as a commercial partner. As a consequence, the current program sees the United States simply as a neighbor and, in the case of the nineteenth century, as an expanding neighbor. As one example of historical change, in the 1970s, the U.S. Intervention of 1847 made no mention of war, as it was called in the United States and today in Mexico.[4] Other events that form part of the curricula are the independence of the thirteen colonies, the presence of the United States in the postwar period, and the struggle for African-American civil rights. The single, free, and compulsory contemporary history textbook of Mexico does not substantially change these versions.[5] For example, the causes of the 1846–1848 conflict reproduce the American vision: because Mexico refused to sell the territory, the U.S. was forced to take it militarily.[6] This is an example of why Peña Nieto is surprised by Trump’s rude remarks: Mexico reconsidered the interpretation of the nation’s past to abandon Latin American identity and, instead, to be part of North America, which shifted Mexico’s gaze toward the United States. However, Mexican neoliberalism has been unable to alter the American perspective of Mexico.

Citizenry, the Future, and Trump

One difference between historiography and the teaching of history is that the first knows it is highly uncertain to predict the future based on the past and the second knows it only exists as it outlines a future. Here, I am faced with a combination of the two. My guess as to what will happen is as follows: the new history program will work collaterally on the Mexico-United States relationship. As like many others, it will promote an artificially sweetened idea of bilateral exchange. Its intention will be to gloss over the tensions—and the fear—produced by Trump in the classrooms. To this should be added the logic of education of the citizenry that, as can be seen in the Modelo Educativo 2016,[7] will provide continuity for the formation of values as the basis of political education. This implies that, instead of teaching the relationships of power between both countries, anti-Mexican racism, the inequality of driving out millions of Mexican workers to the United States, or social rights attacked by NAFTA, the concepts of respect and tolerance will be promoted.

In contrast, an alternative vision demands that the educational model be based on a vision of a critically trained citizenry. This implies seeing the Mexico-United States relationship from a multidimensional perspective. It is about analyzing, in the classroom, the conditions of subordination—and in many cases of resistance—in under which we have lived for two hundred years, but also to about understanding the infinite ways kinds of interrelations between the citizens of both countries beyond State institutions; in other words, also comprehending the ways kinds of positive interaction that have arisen between ordinary Mexicans and Americans… or at least, with those who did not vote for Trump.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Terrazas y Basante, María Marcela, Gerardo Gurza Lavalle, Paolo Riguzzi, and Patricia de los Ríos, Las relaciones México-Estados Unidos: 1756–2010. Mexico City: UNAM, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, 2012.

- Zoraida, Josefina, and Lorenzo Meyer, México frente a Estados Unidos: (un ensayo histórico 1776–1988). Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1982.

Web Resources

- National Commission of Free Textbooks. SEP: Historia. Quinto Grado. Mexico 2016: http://libros.conaliteg.gob.mx/content/common/consulta-libros-gb/index.jsf?busqueda=true&nivelEscolar=5&grado=8&materia=45&editorial=&tipo=&clave=&titulo=&autor=&key=key-5-8-45 (last accessed 12 April 2017).

- Teacher Network, Planeación Interactiva de educación básica: https://www.redmagisterial.com/planea/secundaria/9-3er/1567-historia/20/(last accessed 12 April 2017).

- National Museum of the Interventions (Museo Nacional de las Intervenciones): http://sic.conaculta.gob.mx/ficha.php?table=museo&table_id=978 (last accessed 12 April 2017).

_____________________

[1] A fundamental text for understanding Mexico-United States relations from contemporary Mexican historiography is María Marcela Terrazas y Basante, Gerardo Gurza Lavalle, Paolo Riguzzi, and Patricia de los Ríos, Las relaciones México-Estados Unidos: 1756–2010. Mexico City: UNAM, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas,2012 Similarly, Lorenzo Meyer’s extensive research is indispensable, particularly: Josefina Zoraida, and Lorenzo Meyer,México frente a Estados Unidos: (un ensayo histórico 1776-1988) Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1982. For a summary from a position closer to integrationism, see Rafael Velásquez Flores,“La política exterior de Estados Unidos hacia México bajo la administración de Barack Obama: cambios y continuidades” Norteamérica 2(2011).

[2] This can easily be seen in the official name of Mexico: United Mexican States.

[3] An example of this integrationism could be seen with the a movement, and a march held on 12 February 12, 2017, called #vibraméxico. This movement, which brought together sectors from Mexico City and high strong economic interests, as well as liberal intellectuals;, in other words, the sectors that promoted and have broadly benefited from NAFTA. This group protested against Trump and demanded more vigorous opposition to U.S. policies on the part of Peña Nieto’s administration to U.S. policies. The phenomenon was interesting, for because, at the same time that they defended rejected a total integration with the United States, they promoted a shared, highly exclusive nationalism, in which everything that did not defend their interests was not patriotic. What they did not see is that Trump’s threats to free trade are not important to most Mexicans, because they have not benefited from the agreement. On the contrary, they are victims of the profound inequality that prevails in Mexico. What indeed does concern the masses is the migration situation and the millions of relatives they have who liveing and working in the United States.

[4] This hygienic way of interpreting the intervention, invasion, or war of the United States against Mexico is not exclusive to compulsory education; it is also a historiographic phenomenon. A comparison of the interpretation of Vásquez and Meyer of 1982 and Terrazas and Gurza of 2012 shows how in the first the idea of intervention or invasion predominates, in other words a powerful nation that attacks another, whereas in the second, the idea of war predominates, that is to say the clash between equals, but in an asymmetric power relationship.

[5] In the fifth grade textbook on the history of independent Mexico, the United States is a significant presence: it is mentioned as msuch as fifty-nine times, plus several references to U.S. government or culture (15), as well asnd others to Americans (5). Among the historical events mentioned are that the United States was one of the first nations to recognize Mexico’s independence, the 1846–1848 war, U.S. pressure on Napoleon III’s army in Mexico, U.S. investments, the intervention of the ambassador in the 1913 coup, the conflictive relations of the post-revolutionary period, the bracero program during World War II, migration to the United States, and, of course, NAFTA. In general, the book employs a cordial tone toward its neighbor to the north.

[6] The text by Howard Zin adopts a much more critical position on the U.S. intervention than the Mexican government today. Howard Zinn, A people’s history of the United States: 1492-present, New York:Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2005.

[7] A discussion of citizen education in Modelos Educativo 2016, from a critical perspective, can be found in Sebastián Plá (in press). “La despolitización del ciudadano. Crítica al Modelo Educativo 2016 desde la pedagogía por la justicia social.” Alicia de Alba and Patricia Ducoing. Educación Básica y Reforma Educativa. Mexico City. UNAM. Instituto de Investigaciones sobre la Universidad y la Educación.

_____________________

Image Credits

Battle of Buena Vista during the Mexican-American War, painting by Carl Nebel 1851, @ wikimedia

Recommended Citation

Plá, Sebastián: Teaching History in Times of Trump. In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 15, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-9124.

Schul-Fächer leiden unter einem ständigen Mangel: während von ihnen eine Antwort auf die Zukunft verlangt wird, macht ihre eigentliche Natur es ihnen gleichzeitig unmöglich, sich mit der Geschwindigkeit der Gegenwart weiter zu entwickeln. Trotzdem gibt es kritische Augenblicke, die sie zwingen, eine sofortige Reaktion zu liefern. Dies ist der Fall für die momentane Beziehung zwischen Mexiko und den Vereinigten Staaten. Weil dies ein sehr weit gefasstes Thema ist, werde ich meine Überlegungen allein auf den nationalen Lehrplan für Geschichte beschränken. Welche Interpretationen der mexikanisch-amerikanischen Beziehungen wird der neue Lehrplan für mexikanische Geschichte empfehlen? Was sollten wir lernen, um eine kritische Bürgerschaft vorzubereiten?

Mexiko – USA

Es ist unmöglich, die komplexen Beziehungen zwischen Mexiko und den Vereinigten Staaten in wenigen Worten zusammenzufassen. Doch sollten zwei für die historische Bildung zentrale Punkte hervorgehoben werden.[1] Der erste existiert seit dem Tag im Jahr 1821, an dem Mexiko unabhängig wurde: die Grenze zu den Vereinigten Staaten. Wir müssen sie nur als einen der zentralen Gründe für den amerikanischen Expansionismus nennen – die Invasion Mexikos durch die Vereinigten Staaten in 1847 und der Verlust von mehr als die Hälfte des nationalen Territoriums. Darauf folgten mehrere Invasionen und andere Arten von Einmischung, einschließlich der Verschwörung um den Putsch von 1913. Die historischen Ereignisse verliehen der mexikanischen Politik einen antiamerikanischen Zug, eine Haltung, die mit dem nordamerikanischen Freihandelsabkommen (NAFTA) aus der politischen Klasse verschwand. Diese Beziehungen wurden überwiegend von den Vereinigten Staaten dominiert.

Der zweite Punkt ist die Multidimensionalität der Beziehung. Sie tritt in einem breiten Spektrum von Ebenen und Dimensionen auf: Politik und transnationale Firmen, MigrantInnen, organisierte Kriminalität, wissenschaftliche Kooperationen, Missionierung, Tourismus, Liebe und die Amerikanisierung bestimmter Bereiche der mexikanischen Kultur. Das historische Ergebnis ist eine extrem paradoxe Geisteshaltung: ungebremste Liebe des Amerikanischen, tödlicher Hass des Gringos. Ungeachtet des Standpunkts ist Amerika ohne Zweifel ein Bestandteil unserer pluralen Identität.[2]

Die USA im mexikanischen Curriculum

Zur Zeit befindet sich Mexiko mitten in einer Lehrplanreform. In diesem Zusammenhang wird auch der Geschichtsunterricht neu definiert. Die neuen Inhalte werden vermutlich in Kürze veröffentlicht. Obwohl es sich hier um eine Angelegenheit von öffentlichem Interesse handelt, weiß keiner etwas darüber. Aus unterschiedlichen Gründen lohnt es sich, zu spekulieren, dass die neuen Geschichtsprogramme wahrscheinlich durch einen oder zweien Historiker entworfen werden, die ihre professionelle Identität und die Verwendung von primären Quellen im Unterricht besonders betonen werden. Ich glaube, dass der mexikanische Nationalismus nicht wesentlich modifiziert und dass die Beziehung zu den Vereinigten Staaten umgangen wird, trotz der brutalen Rhetorik Trumps. Angesichts der Zeitgebundenheit schulischen Unterrichts wird das Programm wohl die integrationistische Vision des NAFTA aufrechterhalten, wodurch es außerstande sein wird, auf die aktuelle Situation einzugehen und sich eine von den Vereinigten Staaten unabhängige Zukunft vorzustellen.

Das, was ich Integrationismus[3] nenne, im Gegensatz zu Trumps als Angriff gedachten Formulierung, liegt in der Gestaltung Mexikos als ein struktureller Teil der amerikanischen Wirtschaft begründet. Nach dieser versöhnlichen Logik behandelt der Schulunterricht die Vereinigten Staaten als Geschäftspartner. Folglich sieht der gegenwärtige Lehrplan die Vereinigten Staaten lediglich als Nachbarn und, im Falle des 19. Jahrhunderts, als expandierenden Nachbarn. Hier ein Beispiel der historischen Änderung: in den 1970er Jahren wurde im Zusammenhang mit der U.S.-Intervention von 1847 vermieden, die Handlungen der Vereinigten Staaten als Krieg zu bezeichnen, wie es damals in den Vereinigten Staaten getan wurde wie es heute in Mexiko getan wird.[4] Andere Ereignisse, die in den Lehrplänen enthalten sind, sind die Unabhängigkeit der dreizehn Kolonien, die Anwesenheit der Vereinigten Staaten in der Nachkriegszeit und der afro-amerikanische Kampf um Bürgerrechte. Das einzige, kostenlose und verpflichtendes zeitgenössisches Lehrbuch für Geschichte in Mexiko enthält keine wesentliche Veränderungen dieser Versionen.[5] So werden als Gründe für den Konflikt von 1846-1848 jene aus amerikanischer Sicht wiedergegeben: weil Mexiko es ablehnte, das Territorium zu verkaufen, waren die Vereinigten Staaten gezwungen, es militärisch einzunehmen.[6] Dieses Beispiel zeigt, warum die unverschämten Bemerkungen Trumps Peña Nieto überraschen: Mexiko überdachte die Interpretation der nationalen Vergangenheit, um die lateinamerikanische Identität aufzugeben und statt dessen ein Teil Nordamerikas zu sein, was Mexikos Blickwinkel in Richtung der Vereinigten Staaten lenkte. Allerdings hat der mexikanische Neoliberalismus die amerikanische Perspektive auf Mexiko nicht verändern können.

Die Bürgerschaft, die Zukunft und Trump

Einer der Unterschiede zwischen Historiographie und dem Geschichtsunterricht ist, dass erstere weiß, dass es sehr unsicher ist, die Zukunft auf der Basis der Vergangenheit vorherzusagen und dass der zweite weiß, dass er nur existiert, indem er eine Zukunft entwirft. Hier bin ich mit einer Kombination von beidem konfrontiert. Meine Mutmaßung zur zukünftigen Entwicklung ist die Folgende: der neue Geschichts-Lehrplan wird begleitend auf die Beziehung zwischen Mexiko und den Vereinigten Staaten wirken. Wie vieles andere wird er eine künstlich versüßte Idee von bilateralem Austausch fördern. Sein Ziel wird es sein, die Spannungen – und die Angst – zu vertuschen, die Trump in den Klassenzimmern erzeugt. Hinzukommen sollte auch die Logik der Bildung der Bürgerschaft, die, wie das Modelo Educativo 2016[7] aufzeigt, Kontinuität für die Bildung von Werten liefern wird, als die Basis für politische Bildung. Das bedeutet, dass nicht die Machtverhältnisse zwischen beiden Ländern zum Unterrichtgegegenstand werden, oder der antimexikanische Rassismus, oder die Ungleichheit, welche Millionen von mexikanischen ArbeiterInnen nach den Vereinigten Staaten zu gehen zwingt, oder die soziale Rechte, die von NAFTA in Frage gestellt werden, sondern ganz allgemein die Konzepte von Respekt und Toleranz.

Im Gegensatz hierzu verlangt eine alternative Vision, dass das Bildungsmodell auf der Vision einer kritisch ausgebildeten Bürgerschaft basiert. Das bedeutet, die Beziehung zwischen Mexiko und den Vereinigten Staaten aus einer multidimensionalen Perspektive gesehen werden müssen. Es geht darum, im Klassenzimmer die Bedingungen der Unterordnung (und in vielen Fällen des Widerstands), unter welchen wir während 200 Jahren gelebt haben, aber auch um das Verständnis für die zahllosen Arten von Verflechtungen zwischen den BürgerInnen beider Länder und jenseits von staatlichen Institutionen zu thematisieren; mit anderen Worten, die Arten von positiven Verflechtungen zu verstehen, die zwischen normalen MexikanerInnen und AmerikanerInnen entstanden sind… oder zumindest mit denen, die Trump nicht wählten.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Maria Marcela Terrazas y Basante u.a. (Hrsg.): Las relaciones México-Estados Unidos: 1756–2010. Mexico City 2012.

- Josefina Zoraida / Lorenzo Meyer: México frente a Estados Unidos: (un ensayo histórico 1776–1988). Mexico City 1982.

Webressourcen

- National Commission of Free Textbooks. SEP: Historia. Quinto Grado. Mexico 2016: http://libros.conaliteg.gob.mx/content/common/consulta-libros-gb/index.jsf?busqueda=true&nivelEscolar=5&grado=8&materia=45&editorial=&tipo=&clave=&titulo=&autor=&key=key-5-8-45 (letzter Zugriff: 12. April 2017).

- Teacher Network: Planeación Interactiva de educación básica: https://www.redmagisterial.com/planea/secundaria/9-3er/1567-historia/20/ (letzter Zugriff: 12. April 2017).

- National Museum of the Interventions: http://sic.conaculta.gob.mx/ficha.php?table=museo&table_id=978 (letzter Zugriff: 12. April 2017).

_____________________

[1] Ein grundlegender Text zum Verständnis der Beziehung Mexiko-Vereinigten Staaten aus zeitgenössischer historiographischer Sicht ist: Maria Marcela Terrazas y Basante u.a. (Hrsg.): Las relaciones México-Estados Unidos: 1756–2010. Mexico City 2012. Ebenso unentbehrlich ist Lorenzo Meyers umfangreiche Forschung, insbesondre: Josefina Zoraida/Lorenzo Meyer: México frente a Estados Unidos: (un ensayo histórico 1776-1988). Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica. Für eine Zusammenfassung von einer Position näher an Integrationismus siehe Rafae 2012; Ders.:La política exterior de Estados Unidos hacia México bajo la administración de Barack Obama: cambios y continuidades. In: Norteamérica 6 (2011).

[2] Dies kann einfach aus dem offiziellen Namen Mexikos gesehen werden: Vereinigte Mexikanische Staaten.

[3] Ein Beispiel dieses Integrationismus liefert eine Bewegung und ein Marsch vom 12. Februar 2017 namens #vibraméxico. Diese Bewegung brachte die Sektoren aus Mexiko-Stadt und starke wirtschaftliche Interessen wie auch die liberalen Intellektuellen zusammen; mit anderen Worten Sektoren, die NAFTA gefördert haben und von ihm weitgehend begünstigt wurden. Diese Gruppe protestierte gegen Trump und verlangte den energischeren Widerstand von der Verwaltung des Peña Nieto. Dieses Phänomen war insofern interessant, weil gleichzeitig zu einer totalen Ablehnung der Integration den Vereinigten Staaten, förderten sie einen geteilten, sehr exklusiven Nationalismus, bei dem alles, was ihre Interessen nicht verteidigte, als nicht patriotisch gesehen wurde. Was sie nicht sahen war, dass Trumps Drohungen in Bezug auf Freihandel für die meisten MexikanerInnen unwichtig sind, weil sie von dem Abkommen nicht profitiert haben. Im Gegenteil, sie sind Opfer der tiefgreifenden Ungleichheit, die in Mexiko herrscht. Was die Massen tatsächlich beschäftigt ist die Situation in Bezug auf Migration und die Millionen ihrer Verwandten, die in den Vereinigten Staaten leben und arbeiten.

[4] Diese hygienische Art, die Intervention, Invasion oder der Krieg der Vereinigten Staaten gegen Mexiko zu interpretieren, gehört nicht ausschließlich zum Pflichtschulunterricht; sie ist auch ein historiographisches Phänomen. Ein Vergleich zwischen der Interpretation von Vásquez und Meyer in 1982 mit der von Terrazas und Gurza im Jahr 2012 zeigt, dass in der ersten die Idee von Intervention oder Invasion überwiegt, oder anders gesagt, eine starke Nation attackiert eine andere. Im zweiten Text herrscht die Idee vom Krieg, d.h. der Konflikt zwischen Gleichen aber in einem asymmetrischen Kräfteverhältnis.

[5] In dem Lehrwerk für die 5. Klasse über die Geschichte des unabhängigen Mexikos sind die Vereinigten Staaten eine signifikante Erscheinung: sie werden bis zu 59 Male erwähnt, hinzu kommen einige Verweise auf die U.S.-Regierung oder Kultur (15) wie auch andere auf AmerikanerInnen (5). Unter den historischen Ereignissen werden erwähnt: die Vereinigten Staaten waren eine der ersten Nationen, die die Unabhängigkeit Mexikos anerkannten, der Krieg von 1846-1848, der Druck der U.S. auf die Armee von Napoleon der Dritter in Mexiko, U.S. Investitionen, die Intervention des Botschafters bei dem Putsch von 1913, die konfliktbeladenen Beziehungen in der Periode nach der Revolution, das Bracero-Programm während des 2. Weltkriegs, Migration in die Vereinigten Staaten und auch natürlich NAFTA. Generell verwendet das Lehrwerk einen freundlichen Tonfall für den Nachbar im Norden.

[6] Der Text von Howard Zin nimmt eine viel mehr kritische Position zu dernU.S.-Intervention ein als die mexikanische Regierung heute. Howard Zinn: A people’s history of the United States: 1492-present. New York 2005.

[7] Eine Diskussion der bürgerschaftlichen Bildung im Modelos Educativo 2016 aus einer kritischen Perspektive befindet sich in: Sebastián Plá: La despolitización del ciudadano. Crítica al Modelo Educativo 2016 desde la pedagogía por la justicia social. In: Alicia de Alba/ Patricia Ducoing: Educación Básica y Reforma Educativa. Mexico City: UNAM. Instituto de Investigaciones sobre la Universidad y la Educación (im Druck).

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

Battle of Buena Vista during the Mexican-American War, painting by Carl Nebel 1851; @ wikimedia

Übersetzung

Jana Kaiser (kaiser /at/ academic-texts. de)

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Plá, Sebastián: Geschichtsunterricht in Zeiten von Trump. In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 15, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-9124.

Copyright (c) 2017 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 5 (2017) 15

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-9124

Tags: Curriculum (Lehrplan), Language: Spanish, Mexico, Populism (Populismus), Trump, USA