Abstract: Attacking the free press is the latest assault on fundamental principles of American democracy that President Trump has launched in 2017.[1] Democratic institutions and principles such as an independent judiciary, the rule of law, separation of powers, and the right to dissent no longer undergird the administration’s daily work and rhetoric. While these principles previously served as unifiers across political parties and divisions, public discussion and politics today are rife with the ignorance and distortion of foundational democratic principles and values.[2]

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10414.

Languages: English, Deutsch

Attacking the free press is the latest assault on fundamental principles of American democracy that President Trump has launched in 2017.[1] Democratic institutions and principles such as an independent judiciary, the rule of law, separation of powers, and the right to dissent no longer undergird the administration’s daily work and rhetoric. While these principles previously served as unifiers across political parties and divisions, public discussion and politics today are rife with the ignorance and distortion of foundational democratic principles and values.[2]

History Teaching in the Age of Trump

As citizens, this is alarming; as educators, it is a clarion call. Many are talking about the implications for teaching in the age of Trump.[3] One thing seems certain from my perch: We must refocus and rethink if and how we are teaching fundamental democratic principles in our classes. And as teacher educators, we must be sure that our students value and deeply understand these ideas so they are prepared to integrate and teach them throughout the curriculum.

After the shocking and dangerous election of Trump to the Presidency, I had several days to struggle with what to do with my history teacher candidates in our next class session. I knew the election of President Trump would impact my students and that they would be anxious to discuss it. I needed to respond appropriately. How to respond, however, was not obvious to me.

Ultimately, I started our next class asking candidates what they had seen in their field placements regarding the election. Some had seen nothing specific—master teachers had continued with their units on Ancient Greece or economic markets. Others had seen teachers provide space for distraught students in immigrant communities to process their fears with trusted adults, or lessons where students discussed voting patterns or the electoral college.

I talked of how this was a choice — if and when to talk about current events in the classroom. I recalled when, in 1989, I was student teaching in an urban high school that served a Chinese-American community, and the Tiananmen Square protests and massacre occurred. Veteran teachers at the school responded quite differently to those events: One insisted that ignoring it in the world history classroom was tantamount to malpractice and another asserted that responding to relevant world events would leave no space for the standard curriculum. I talked to my teacher candidates about how these were decisions that they would face.

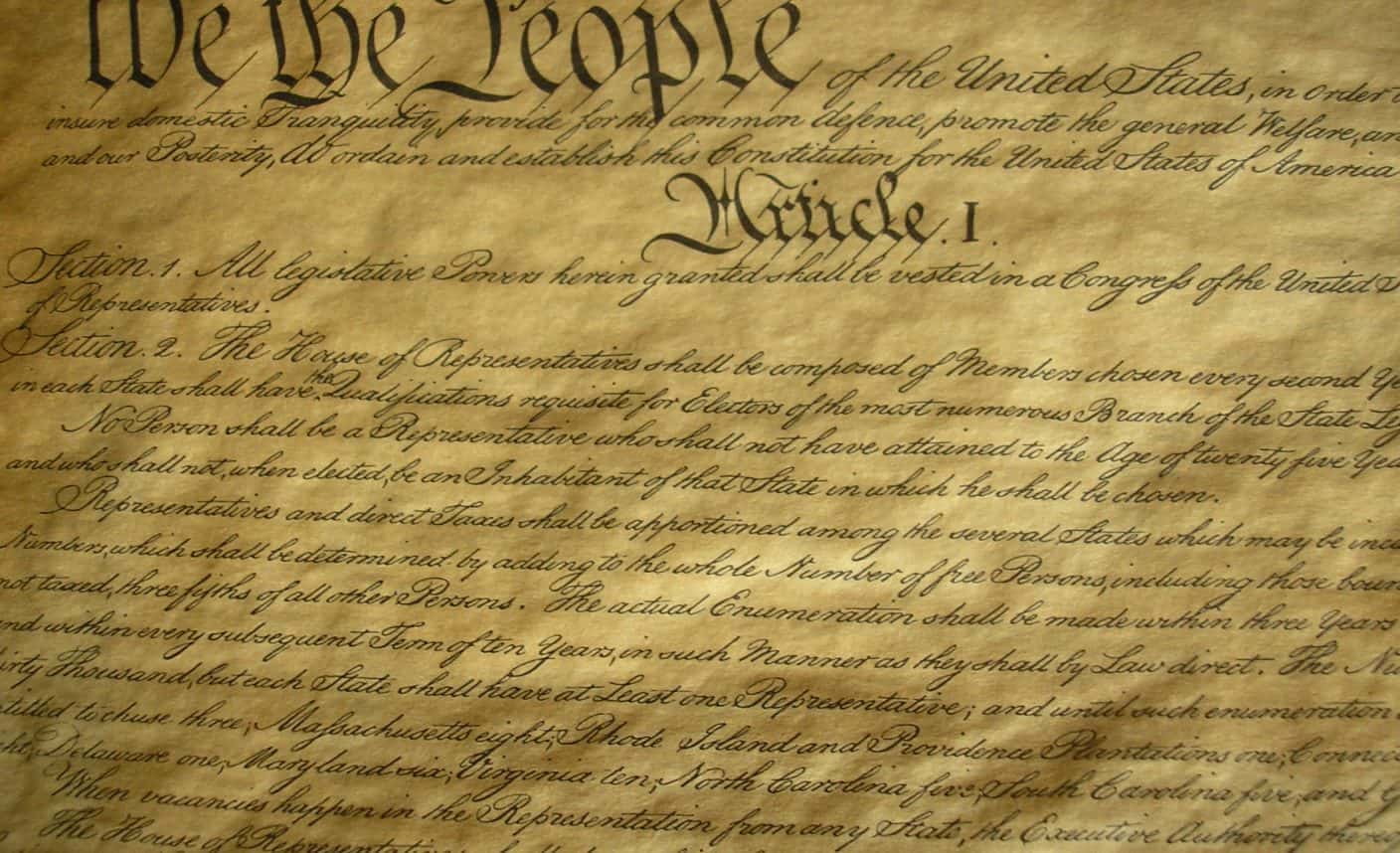

I then launched into the next part of my deliberate response, a lesson on democratic principles and the U.S. Constitution. After teaching prior cohorts, I knew that some of these candidates did not have a firm grasp on fundamental democratic principles (for example: rule of law) and their worth, or on aspects of the Constitution that are critical to understanding the American past and present (for example: the Fourteenth Amendment).[4] I followed my usual pedagogical approach where teacher candidates experience a learning activity or resource as learners before putting on their teacher hats to debrief the research and theory undergirding the activity. This approach means, in part, that candidates learn content while also considering the teaching of that content. Importantly, in this instance, I chose democratic ideas and institutions as essential content that these future teachers needed to deeply understand. I was not willing for any of them to leave my class without being ready to teach and use these principles in their own classrooms.

We Don’t Teach in a Vacuum

When 9/11 happened in 2001, I had a vigorous debate with my co-teachers about addressing it in our methods for teaching history course. I lost. My colleagues’ certainty about excluding unexpected world events seemed to assume the classroom as teacher-controlled and vacuum-sealed, a place where students neither knew nor cared what happened outside it. It created an impenetrable wall between classroom and community, where these events did not, and would not, impact student learning. I did not understand this stance. How could we be teaching civics and history without bringing the world outside our classroom into it? How could this be preparing students to participate in civic life and discourse?

So it is good to see that the age of Trump has prompted educators and scholars to consider what it means to teach in these times. For example, Peter Seixas advises us to revisit our general approach to modern liberal traditions and how we address them in our work as teachers.[5] More specifically, scholars have called for the teaching of historical thinking, and web literacy and how to discern fake news.[6] Thinkers agree that this is an unprecedented and dangerous time for democratic institutions and values in the U.S., and that history educators and researchers have a moral, if not professional, obligation to consider what we teach in light of this challenge.[7]

Teaching Democracy

So what, of the many and myriad things that we teach and value, should we emphasize and focus on in classrooms today? In other words, what deserves more curricular time? More student work and investigation?

Democratic ideas, values, and knowledge are all paramount at this moment. Of course, historical thinking and web literacy are also important, but these have been emphasized (to different degrees) for some years in our professional discourse. Conversely, teaching democracy may be “so fundamental that history educators barely gave [it] a passing thought” in the recent past.[8] It is time to pull these principles out and to give them a place of privilege in the crowded history and civics curriculum. It is time to be sure to integrate them into multiple lessons so that students apply them in a variety of ways over a course of study.

Let us also take this moment to acknowledge that the recent past and present should always matter to history educators. As teacher educators, we need to teach that a history and civics teacher’s lens must include contemporary events and the zeitgeist of public worlds outside the classroom. When candidates enter their own classrooms, this message will be muted if not absent. These future teachers not only need to know democracy; they also need to know ways to think about how to bring the world into their own classrooms.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Seixas, Peter. “History Educators in a New Era.” Public History Weekly 2017, 25 May 2017. https://doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-9343 (last accessed on 30 October 2017).

- The Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania. “Americans Are Poorly Informed About Basic Constitutional Provisions.” https://www.annenbergpublicpolicycenter.org/americans-are-poorly-informed-about-basic-constitutional-provisions/ (last accessed on 30 October 2017).

Web Resources

- Civics Renewal Network, Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania. “CivicsRenewalNetwork.org: A Republic, If We Can Teach It.” https://www.civicsrenewalnetwork.org/ (last accessed on 30 October 2017).

- National Council for the Social Studies. “College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework for Social Studies State Standards: Guidance for Enhancing the Rigor of K-12 Civics, Economics, Geography, and History.” https://www.socialstudies.org/sites/default/files/2017/Jun/c3-framework-for-social-studies-rev0617.pdf (last accessed on 30 October 2017).

- Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, podcast. “BackStory.” http://backstoryradio.org/about/ (last accessed on 18 October 2017).

_____________________

[1] Donald J. Trump, “Network news has become so partisan, distorted and fake that licenses must be challenged and, if appropriate, revoked. Not fair to public!,” Twitter post, October 11, 2017, https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump (last accessed on 18 October 2017).

[2] Find a recent example in Josh Delk, “Roy Moore: Kneeling during National Anthem Disrespects Rule of Law,” The Hill, October 11, 2017, http://thehill.com/blogs/blog-briefing-room/354918-roy-moore-kneeling-during-national-anthem-disrespects-rule-of-law (last accessed on 30 October 2017).

[3] E.g. John Fea, “The Discipline of the History Professor in the Age of Trump,” The Panorama, September 13, 2017, http://thepanorama.shear.org/2017/09/13/the-discipline-of-the-history-professor-in-the-age-of-trump/ (last accessed on 30 October 2017); David Pace, “The History Classroom in an Era of Crisis: A Change of Course Is Needed,” Perspectives on History, May 2017, https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/may-2017/the-history-classroom-in-an-era-of-crisis-a-change-of-course-is-needed (last accessed on 30 October 2017); Gautham Rao, “Roundtable: Teaching History in the Trump Era,” The Junto, August 8, 2017, https://earlyamericanists.com/2017/08/08/roundtable-teaching-history-in-the-trump-era/ (last accessed on 30 October 2017); Clint Smith, “James Baldwin’s Lesson for Teachers in a Time of Turmoil,” The New Yorker, September 23, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/james-baldwins-lesson-for-teachers-in-a-time-of-turmoil (last accessed on 30 October 2017).

[4] These teacher candidates are all graduate students who have chosen a career in teaching history and social science. One might therefore assume that they understand these principles, but I have not found this to be true. This is consistent with what recent surveys and tests have indicated about the general public in the U.S. See “Americans Are Poorly Informed About Basic Constitutional Provisions,” The Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania, September 12, 2017, https://www.annenbergpublicpolicycenter.org/americans-are-poorly-informed-about-basic-constitutional-provisions/ (last accessed on 30 October 2017); “2014 Overall Civics Scores,” NAEP, https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/hgc_2014/#civics/scores (last accessed on 30 October 2017).

[5] Peter Seixas, “History Educators in a New Era.” Public History Weekly 2017, May 25, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-9343 (last accessed on 30 October 2017).

[6] David Pace, “The History Classroom in an Era of Crisis.”; Sarah McGrew, Teresa Ortega, Joel Breakstone, and Sam Wineburg, “The Challenge That’s Bigger Than Fake News,” American Educator, Fall 2017, https://www.aft.org/ae/fall2017/mcgrew_ortega_breakstone_wineburg (last accessed on 30 October 2017).

[7] Pace, “The History Classroom in an Era of Crisis”; Seixas, “History Educators in a New Era”; Fea, “The Discipline of the History Professor in the Age of Trump.”

[8] Seixas, “History Educators in a New Era.”

_____________________

Image Credits

US Constitution © Jonathan Thorne via Flickr (last accessed on 9 November 2017).

Recommended Citation

Martin, Daisy: Focusing on Democracy: A Teacher Educator’s. In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 38, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10414.

Die Kritik an der freien Presse bildet den jüngsten Anschlag Donald Trumps auf die US-amerikanische Demokratie.[1] Demokratische Institutionen und Prinzipien wie eine unabhängige Justiz, die Rechtsstaatlichkeit, die Gewaltenteilung und das Recht auf Widerspruch sind nicht mehr die Basis für die Politik der Regierung. Während diese Prinzipien über die politischen Parteien hinweg lange Zeit akzeptiert wurden, sind öffentliche Debatten und die heutige Politik von Ignoranz und Verzerrung demokratischer Grundsätze und Werte geprägt.[2]

Geschichtsunterricht in Zeiten von Trump

Für BürgerInnen ist das alarmierend, für LehrerInnen ein Weckruf. Viele diskutieren über die Auswirkungen der Ära Trumps auf die Lehre.[3] Aus meiner Sicht ist eines klar: Wir müssen uns neu fokussieren und umdenken, ob und wie wir demokratische Prinzipien im Unterricht vermitteln können. Außerdem müssen wir uns als Lehrende in der LehrerInnenausbildung sicher sein, dass StudentInnen diese Ideen wertschätzen und auch verstehen, damit sie selbst imstande sind, diese zu unterrichten.

Nach dem schockierenden Wahlausgang, der Trump zum Präsidenten machte, kämpfte ich einige Tage mit der Entscheidung, was ich mit meinen Studierenden in der nächsten Stunde thematisieren sollte. Ich wusste, dass die Wahl Trumps die StudentInnen beschäftigen würde und sie darüber sprechen wollen. Ich musste dementsprechend reagieren: Wie ich allerdings darauf reagieren sollte, darüber war ich unschlüssig.

Letztlich fragte ich die Studierenden, was ihnen an ihrem jeweiligen Praktikumsplatz in Bezug auf das Wahlergebnis aufgefallen sei. Einige hatten nichts Besonderes erlebt. Andere hatten beobachtet, dass LehrerInnen für verstörte SchülerInnen mit Migrationshintergrund Zeit einräumten, um über deren Ängste zu sprechen. Während des Unterrichts war auch über die Wahltendenzen oder das Wahlkollegium diskutiert worden.

Ich erwähnte, dass es jedem freigestellt sei, ob und wann über tagesaktuelle Ereignisse im Klassenzimmer geredet wird: Ich erinnerte mich an das Jahr 1989, als ich an einer städtischen Mittelschule in einem chinesisch-amerikanischen Stadtteil unterrichtete, als die Proteste und das Massaker am Tian’anmen-Platz stattfanden. Erfahrene LehrerInnen dieser Schule reagierten sehr unterschiedlich: Ein Kollege bezeichnete es als verantwortungslos, die Ereignisse im Geschichtsunterricht zu ignorieren; ein anderer behauptete, dass durch die Auseinandersetzung mit dem aktuellen Weltgeschehen das Curriculum vernachlässigt würde. Ich wies die Studierenden darauf hin, dass ihnen diese Entscheidungen noch bevorstünden.

Danach thematisierte ich die demokratischen Grundsätze und die Verfassung der Vereinigten Staaten. Aus Erfahrung wusste ich, dass einige der Studierenden nur wenig über demokratische Prinzipien oder die Verfassung, die für das Verständnis der US-amerikanischen Vergangenheit und Gegenwart relevant sind, informiert sein würden.[4] Ich verfolgte meinen üblichen pädagogischen Ansatz, bei dem Studierende als SchülerInnen mit einer Lernaktivität oder Quelle konfrontiert werden, bevor sie sich in die Rolle des Lehrenden begeben, um die Recherche und die Theorie, die der Aktivität zugrunde liegt, zu reflektieren. Damit setzen sich die Studierenden sowohl mit dem Inhalt als auch mit der Lehrmethode auseinander. Sie sollten meinen Unterricht als kompetente LehrerInnen verlassen, die demokratische Grundsätze für ihr eigenes Lehren anwenden können.

Wir lehren nicht in einem Vakuum

Als sich 9/11 ereignete, diskutierte ich mit einigen LehrerkollegInnen darüber, wie man die jüngsten Ereignisse in den Unterricht integrieren könne. Im Gegensatz zu mir waren meine KollegInnen der Meinung, dass für unvorhergesehene Weltgeschehnisse im Klassenzimmer kein Platz sei. Unterricht sollte ihrer Meinung nach in einem lehrerzentrierten Vakuum stattfinden, in dem SchülerInnen sich mit der Welt außerhalb des Klassenzimmers nicht beschäftigen. Ein solcher Unterricht schafft eine undurchdringliche Barriere zwischen Klassenzimmer und Gesellschaft. Wie sollen wir aber Staatskunde und Geschichte lehren, ohne dabei die Welt in die Klassenzimmer zu bringen? Wie sollen SchülerInnen befähigt werden, an der Gesellschaft zu partizipieren?

Glücklicherweise hat die Ära Trumps LehrerInnen und WissenschaftlerInnen dazu veranlasst, über den Unterricht in der heutigen Zeit nachzudenken. Peter Seixas rät zum Beispiel dazu, unsere Herangehensweise an moderne liberale Traditionen und deren Umsetzung im Unterricht grundlegend zu überdenken.[5] Im Besonderen fordern WissenschaftlerInnen, historisches Denken, Internetkompetenz und den Umgang mit Fake News vermehrt zum Unterrichtsgegenstand zu machen.[6] Sie sind sich darüber einig, dass die demokratischen Institutionen und Werte der Vereinigten Staaten einer nie dagewesenen Bedrohung ausgesetzt sind und GeschichtslehrerInnen und ForscherInnen ihrer moralischen und professionellen Pflicht nachkommen müssen, ihren Unterricht neu zu konzipieren.[7]

Demokratie lehren

Was sollen wir heute unter den unzähligen Themen, die unterrichtet werden sollen, besonders hervorheben? Anders gefragt, was verdient besondere curriculare Zeit?

Historisches Denken und Internetkompetenz, die im professionellen Diskurs jahrelang hervorgehoben wurden, sind freilich wichtig. Demokratiebildung mag in den letzten Jahren so selbstverständlich erschienen sei, dass GeschichtslehrerInnen kaum darüber nachdachten.[8] Es ist allerdings Zeit, demokratischen Ideen, Werten und Wissen einen prestigeträchtigeren Platz im Unterricht zu geben.

Die jüngste Vergangenheit und die Gegenwart sollten im Geschichtsunterricht stärkere Bedeutung erhalten. Die LehrerInnenausbildung muss die Studierenden befähigen, zeitgenössische Ereignisse und den gesellschaftlichen Zeitgeist in den Geschichts- und Staatskundeunterricht zu implementieren. Die zukünftigen LehrerInnen müssen nicht nur über Demokratie Bescheid wissen, sondern auch einen Weg finden, wie man die Welt in das Klassenzimmer bringt.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Seixas, Peter. “History Educators in a New Era.” Public History Weekly 2017, 25. Mai 2017. https://doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-9343 (letzter Zugriff am 30. Oktober 2017).

- The Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania. “Americans Are Poorly Informed About Basic Constitutional Provisions.” https://www.annenbergpublicpolicycenter.org/americans-are-poorly-informed-about-basic-constitutional-provisions/ (letzter Zugriff am 30. Oktober 2017).

Webressourcen

- Civics Renewal Network, Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania. “CivicsRenewalNetwork.org: A Republic, If We Can Teach It.” https://www.civicsrenewalnetwork.org/ (letzter Zugriff am 30. Oktober 2017).

- National Council for the Social Studies. “College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework for Social Studies State Standards: Guidance for Enhancing the Rigor of K-12 Civics, Economics, Geography, and History.” https://www.socialstudies.org/sites/default/files/2017/Jun/c3-framework-for-social-studies-rev0617.pdf (letzter Zugriff am 30. Oktober 2017).

- Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, podcast. “BackStory.” http://backstoryradio.org/about/ (letzter Zugriff am 30. Oktober 2017).

_____________________

[1] Donald J. Trump, “Network news has become so partisan, distorted and fake that licenses must be challenged and, if appropriate, revoked. Not fair to public!,” Twitter post, 11. Oktober 2017, https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump (letzter Zugriff am 18. Oktober 2017).

[2] Ein aktuelles Beispiel findet sich in Josh Delk, “Roy Moore: Kneeling during National Anthem Disrespects Rule of Law,” The Hill, 11. Oktober 2017, http://thehill.com/blogs/blog-briefing-room/354918-roy-moore-kneeling-during-national-anthem-disrespects-rule-of-law (letzter Zugriff am 30. Oktober 2017).

[3] Zum Beispiel John Fea, “The Discipline of the History Professor in the Age of Trump,”The Panorama, 13. September 2017, http://thepanorama.shear.org/2017/09/13/the-discipline-of-the-history-professor-in-the-age-of-trump/ (letzter Zugriff am 30. Oktober 2017); David Pace, “The History Classroom in an Era of Crisis: A Change of Course Is Needed,” Perspectives on History, Mai 2017, https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/may-2017/the-history-classroom-in-an-era-of-crisis-a-change-of-course-is-needed (letzter Zugriff am 30. Oktober 2017); Gautham Rao, “Roundtable: Teaching History in the Trump Era,” The Junto, 8. August 2017, https://earlyamericanists.com/2017/08/08/roundtable-teaching-history-in-the-trump-era/ (letzter Zugriff am 30. Oktober 2017); Clint Smith, “James Baldwin’s Lesson for Teachers in a Time of Turmoil,” The New Yorker, 23. September 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/james-baldwins-lesson-for-teachers-in-a-time-of-turmoil (letzter Zugriff am 30. Oktober 2017).

[4] Diese angehenden LehrerInnen sind alle AbsolventInnen, die beschlossen haben, das Unterrichten von Geschichte und Sozialkunde zum Beruf zu machen. Daher könnte man meinen, dass diese Prinzipien von ihnen verstanden werden, jedoch habe ich mich vom Gegenteil überzeugen müssen. Dies stimmt auch mit den Ergebnissen jüngster Umfragen und Tests über die breite US-amerikanische Öffentlichkeit überein. Siehe: “Americans Are Poorly Informed About Basic Constitutional Provisions,” The Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania, 12. September 2017, https://www.annenbergpublicpolicycenter.org/americans-are-poorly-informed-about-basic-constitutional-provisions/ (letzter Zugriff am 30. Oktober 2017); “2014 Overall Civics Scores,” NAEP, https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/hgc_2014/#civics/scores (letzter Zugriff am 30. Oktober 2017).

[5] Peter Seixas, “History Educators in a New Era.” Public History Weekly 2017, 25. Mai 2017, https://doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-9343 (letzter Zugriff am 30. Oktober 2017).

[6] David Pace, “The History Classroom in an Era of Crisis.”; Sarah McGrew, Teresa Ortega, Joel Breakstone und Sam Wineburg, “The Challenge That’s Bigger Than Fake News,” American Educator, Herbst 2017, https://www.aft.org/ae/fall2017/mcgrew_ortega_breakstone_wineburg (letzter Zugriff am 30. Oktober 2017).

[7] Pace, “The History Classroom in an Era of Crisis”; Seixas, “History Educators in a New Era”; Fea, “The Discipline of the History Professor in the Age of Trump.”

[8] Seixas, “History Educators in a New Era.”

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

US-Verfassung © Jonathan Thorne via Flickr (letzter Zugriff am 9. November 2017).

Übersetzung

Stefanie Svacina and Paul Jones (paul.stefanie at outlook.at)

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Martin, Daisy: Demokratie im Fokus: Positionen einer LehrerInnenausbildenden. In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 38, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10414.

Copyright (c) 2017 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 5 (2017) 38

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10414

Tags: Civics Education (Politische Bildung), Democracy (Demokratie), Populism (Populismus), Trump, University teaching (Hochschuldidaktik), USA