Abstract: Three authors address the potential for the emergence of transnational audiences for public history. In December 2020, the Okinawa Memories Initiative hosted an online event commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Koza Uprising, a violent response by Okinawans to repeated harms perpetrated US military personnel, and a strong conviction on the part of the participants that justice for Okinawans had been systematically denied. Through interviews with an eyewitness to the uprising, a U.S. Army veteran who experienced an ethnic identity awakening while stationed in Okinawa just prior to the Uprising, and two members of the Okinawan community in diaspora, the online event invited a multinational audience to consider an incident on a small island under U.S. military occupation as a part of their own local histories. The Koza Uprising event took place in the seventh month of nation-wide (and worldwide) protests in the wake of the murder by Minneapolis Police of George Floyd. As such, a remembrance of a pivotal event protesting the lack of accountability of US military forces in Okinawa spoke as well to the protests against the lack of accountability of policing of black and brown communities in the U.S. As with Brzycki and Montgomery, the articulation of the past into the crises of the present moment played an important role.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-18602

Languages: English

How does transnational public history transcend national reification and local orientation? We discuss the Okinawa Memories Initiative’s commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Koza Uprising and the emergence of new meanings of the Uprising in the memories of Okinawan civilians, U.S. military personnel, and activists within the Okinawan diaspora.

What Happened at Koza?

“It’s not that I’m Anti-American,” Kuniyoshi Kazuo told me emphatically as I [Richardson] sat in an Okinawa City A&W preparing for the Okinawa Memories Initiative’s (OMI) Koza Uprisingevent.[1] “It’s that I’m anti-military, and there’s a difference.” Kuniyoshi’s distinction wards against early classifications of the Koza Uprising as an “Anti-American Riot.”[2]

Kuniyoshi’s distinction is not unusual: a January 10, 1971 survey of local opinion by Far East Broadcasting Co., a Christian radio network, concluded that the “riot was not a riot in the usual sense. No damage was done to stores or buildings, no one was killed. When an American serviceman’s car was attacked the occupants were pulled from the car before it was sent on fire… it was neither an anti-American nor a racial riot; it was anti-military.”[3]

And yet the Koza Uprising was a racialized event. On the night of December 20, 1970, as American cars were being burned and molotov cocktails thrown, calls echoed for Okinawans not to hurt the Black GIs.[4] The city of Koza — now rebranded as Okinawa City — was an American base town formed in the shadows of Air Force Base Kadena but in close proximity to Marine Corps and Army bases as well. It was deeply segregated. This segregation of Black and White soldiers in the U.S. military was mapped onto the city of Koza, a new layer of racialization on top of the entrenched othering of Okinawans by the Japanese empire.

What does it mean to reinforce a national identity when that identity is one that is deeply informed by diasporic transnationalisms and, as is the case with Okinawa, a historically on-again-off-again relationship with Japan? Within the last 150 years, Okinawa has existed as the mostly autonomous Ryukyu Kingdom, a Japanese prefecture (from 1879), a U.S. military colony (1945-1972) and now once again a prefecture that ostensibly guarantees Okinawans equal access to the rights of Japanese citizenship. Throughout each of these periods, Okinawans migrated abroad and built new lives in new communities around the world, particularly in Hawai’i and Latin America.

Local memories of the 1970 Koza Uprising, when they can be found at all, are diffused through histories and experiences rooted far beyond the Okinawa archipelago. This makes Okinawa an illuminating space to explore transnational public history. The Koza Uprising is a ripe example of transnational public history because it defies any particular locality. Memories of the event resonate differently within Okinawa, the U.S. military, and the diaspora. Only by examining how the impact of the uprising in these different communities can we understand what the Koza Uprising has come to mean.

Picturing Rebellion

Kuniyoshi reiterates: he’s not Anti-American and that distinction matters because he wants to have a dialogue with Americans. He was in his early twenties and only six months on the job as a photojournalist for the local Ryukyu Shimbun when he was eyewitness to the Koza Uprising on Dec 20th, 1970. The experience was transformative.

He mentioned how his generation grew up alongside American culture and rock music and that these were formative elements of his upbringing; on the other hand, he recounted with practiced ease an enumeration of the military crimes and accidents that punctuated life in the shadows of military bases. In the case of the Koza Uprising, the most recent causes of discontent, Kuniyoshi explained, were the failures of U.S. military accountability in the prosecution of vehicular homicide by drunk servicemen and the continued storage and transportation of toxic gas on the island, not to mention the continuing American war in Vietnam.

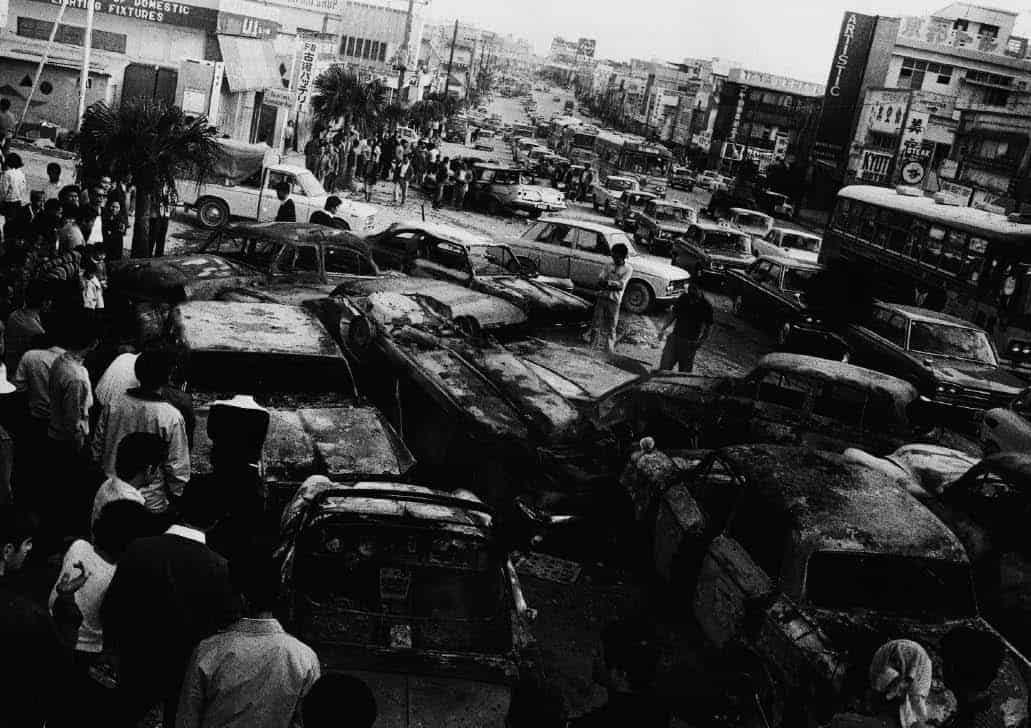

He related to me the story behind each photograph in his collection, appropriately titled Stand![5] The night of the uprising, protestors feared identification by police, and he was pressured to take all his shots without a flashlight. The resulting images are studies in contrast – silhouettes of cars illuminated in luminous smoke and the blurred motion of figures in 3am darkness. By the following day the aftermath had become an event in itself. The U.S. military had made a pile of the burnt-out cars in the center of the road and spectators gathered to survey the damage. They smiled for Kuniyoshi’s camera and a young boy in sandals walked, perhaps triumphantly, atop the blackened hood of a military sedan.

This photo is one of Kuniyoshi’s favorites. Though it was a single, fleeting instant– the boy hopped down soon after — Kuniyoshi finds it a rare and invigorating moment. For those few seconds it was possible to envisage an Okinawa free from military bases; Okinawans had done something and a new future was almost imaginable.

Then, reversion happened, and while so much changed, so much stayed the same. Okinawa was returned to Japan and was once again a prefecture under Japanese sovereignty. It is no longer possible for Okinawans to appeal directly to the U.S. military about the bases. Instead, the Japanese government mediates their complaints, and it seems to Kuniyoshi that there is a breakdown in communication, which is why he wants to have this dialogue — to speak to Americans directly.

Diasporic (Re)Discoveries

While the Koza Uprising stands out as one of the most important anti-base demonstrations in Okinawan history, many diasporic Okinawans had never heard about it. Though news of the uprising was not concealed, it was a political event that happened after many Okinawans had already moved across the world. It was not packed alongside the histories of the Ryukyu Kingdom or cultural practices of Obon or Shiimi in the mental luggage of Okinawan emigrants.

This is changing, however, as many diasporic Okinawans are re-discovering the event in new contexts. For diasporic Okinawans today, the Koza Uprising represents an earlier moment of activism and protests that joins in a lineage from the Ferguson protests of 2014 to the protests in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in 2020. The identity of young Okinawans, particularly in the diaspora, is being shaped by the Black Lives Matters movement and we [McClellan-Ufugusuku] are reconsidering our relationship to our ancestral homelands and solidarity. Anti-racist activism is not new to Okinawa: before the uprising at Koza, protestors marched in solidarity with the late Dr. Martin Luther King, and the Black Panther Party had a significant island presence. Indigenous activism has been equally influential for diasporic Okinawans and many participated in the Thirty Meter Telescope protests at Mauna Kea (2014) and the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline (2016).

The COVID-19 pandemic opened new spaces for commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the Koza Uprising. Like most of the world, Okinawans, diasporic and otherwise, have been forced online by the global pandemic. By December 2020, Okinawan diasporic organizations had already been providing public, online educational programming for almost nine months, about topics such as mixed-race Okinawans (Ukwanshin Kabudan), remembering the battle of Okinawa (Hawai’i United Okinawan Association), and Afro-Okinawan dialogues in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in May of 2020 (Okinawa Association of America).

The Revisiting The Koza Uprising in Global Perspectives /「コザ騒動を世界の視点で」was the largest and most successful event that the Okinawa Memories Initiative has so far conducted. We owe part of our success to these diasporic communities for laying the foundation for connecting many populations on and off base, in Okinawa, the United States, and South America. Our 50th anniversary event was necessarily ambitious for the type of dialogue we hoped to create — a synchronous event with six different speakers, seven time zones apart, and simulcast in two different languages (English and Japanese). We juxtaposed photos from the Uprising with a contemporary walking tour video of Gate-2 Street in Koza, the scene of the riot fifty years earlier.

Memories Beyond the Nation

The act of commemorating historical events has its limits and challenges. On the one hand, commemorations often attempt to fit unrelated events into a consistent and affirming or lesson-teaching narrative. The result can sometimes be a clumsy telling of history that cleanses past events of their specific contexts. State commemorations “stake a claim for what is most important to remember in order to reinforce national identity for coming generations,” a process that Shanti Sumartojo argues allows states to “shore up official versions of national identities.”[6] Remembering events of the past is, of course, often driven by a desire to better understand the present.

The hegemonic narrative of the Ryukyu islands, dating back at least to Basil Hall’s visit to “Loochoo” in 1816, is that Ryukyuans are a peaceful people not given to conflict, violence, or revolt. For Okinawans who viewed the Uprising as a solitary disruption of American rule in Okinawa, Stan Rushworth’s narrative of Okinawan resistance was eye-opening. For our “Revisiting” event, I [Wright] interviewed Stan, who arrived in Okinawa as a young American soldier in August of 1963. Stan spoke of his arrival in Okinawa as one in which the racial violence within the military was as ubiquitous as the island’s subtropical heat, reaching a crescendo as the Vietnam War lingered and Okinawa’s ‘reversion’ to Japan seemed forever just beyond reach. Americans who were stationed in Okinawa during the Vietnam War era were often both the progenitors and victims of racial and military violence.

Stan told the nearly 400-person Zoom audience, “What I ran into when I got to Okinawa was an incredible amount of fear, and fear has a nasty little brother called ‘anger,’ and that anger creates hatred and creates dehumanization.” He was welcomed to his first night in the Camp Zukeran barracks by a guard with a .45 caliber submachine gun, who protected sleeping White soldiers from fellow Black soldiers, who in turn had their own guards protecting them. 1960’s headlines in the Okinawan press, even years after Stan returned to the U.S., made clear the centrality of race in basetowns like Koza: “Black Riot in Koza Bar District,” “Another Raucous U.S. Soldier Fight,” “Hostess Receives Serious Injuries: Hit by White Soldier,” “Black Soldier Fires Gun in Kin Town.”[7]

While the danger and violence in these base-town environments were certainly obvious to Okinawans of the era, commemorating the Uprising helped some listeners to look again at their memories of the young soldiers they encountered. After the online commemoration, some Okinawans reflected that Stan’s experience opened up a new understanding that American soldiers, who were the progenitors of much of the basetime violence, were often also among its terrified victims. Far from reinforcing a singular national narrative, OMI’s digital commemoration of the Koza Uprising helped illuminate transnational and diasporic memories of Okinawa’s Vietnam era.

Okinawan Futures

Can these separate memories find a new dimension where they do not assimilate with each other but can resonate in productive dialogue? That was the central question of the Okinawa Memories Initiative’s experiment. What the experiment revealed was not merely three differing accounts of a localized event, or the bringing together of discordant memories, but an interweaving of imagined futures.

For Stan Rushworth, the Uprising was an inevitable outcome of racial and gendered violence. From his perspective as a member of the occupying military, the fear for his life and experience of acts of resistance made rebellion seem an inevitability. This is in stark contrast to the views of Okinawan civilians like Kuniyoshi, for whom the Uprising was understood to be an unusually violent and singular moment in the history of anti-base protest. It was not anti-American but anti-military, attentive to a complexity of racial dynamics, and the fleeting instance of revolutionary potential when change seemed possible. For Okinawan activists in the diaspora discovering the Uprising for the first time, the rebellion reshapes ideas about Okinawa and its history: it reveals a lost revolutionary potential and reckoning with questions of racism and indigeneity that evoke futures of not only Okinawa but the United States.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Ueunten, Wesley Iwao. “Rising Up from a Sea of Discontent: The 1970 Koza Uprising in U.S.-Occupied Okinawa,” Militarized Currents: Towards a Decolonized Future in Asia and the Pacific, Eds. Setsu Shigematsu and Keith L. Camacho, (Minneapolis: Minnesota UP, 2010).

- 米国が見たコザ暴動 [The Koza Riot As Seen By the U.S.]. Eds. 沖縄市企画部平和文化振興課 [Okinawa City Planning for the Promotion of Peace Culture]. (Okinawa: Yui Shuppan, 1999).

- Shimabuku, Annmaria M. “Okinawa, 1958-1972: The Subaltern Speaks.” Alegal: Biopolitics and the Unintelligibility of Okinawan Life. (New York: Fordham UP, 2019).

Web Resources

- “The Koza Uprising,” Okinawa Memories Initiative: https://okinawamemories.org/the-koza-uprising/ (last accessed 27 June 2021).

- “コザ騒動50年 爆発した基地の街の怒り [The Koza Rebellion at 50 Years: The Anger that Exploded at a Base Street].” Ryūkyū Shimpō, 20 December 2020: https://ryukyushimpo.jp/special/kozariot1970.html (last accessed 4 July 2021).

- “1970年12月20日、21日「コザ暴動」ーあの日の屋良主席 ー [December 20th and 21st, 1970: ‘Koza Rebellion’ Governor Yara on That Day].” Okinawa Prefectural Archive: https://www.archives.pref.okinawa.jp/news/that_day/119 (last accessed July 4 2021).

_____________________

[1] Due to the political nature of this rebellion we have opted to call this event an uprising, following the arguments of Wesley Iwao Ueunten in “Rising Up from a Sea of Discontent: The 1970 Koza Uprising in U.S.-Occupied Okinawa,” Militarized Currents: Towards a Decolonized Future in Asia and the Pacific, Eds. Setsu Shigematsu and Keith L. Camacho, (Minneapolis: Minnesota UP, 2010).

[2] Kanda, Yoshiyuki. “Anti-American Riot on Okinawa.” Mainichi Daily News, Dec. 22nd, 1970.

[3] Austin, Arthur C. “Special Report to Robert H. Bowman, President Far East Broadcasting Co., Inc.” in 米国が見たコザ暴動 [The Koza Riot As Seen By the U.S.], Eds. 沖縄市企画部平和文化振興課 [Okinawa City Planning for the Promotion of Peace Culture], (Okinawa: Yui Shuppan, 1999): 270.

[4] Ueunten, Wesley Iwao. “Rising up from a Sea of Discontent,” in Setsu Shigematsu and Keith Camacho Militarized Currents: Toward a Decolonized Future in Asia and the Pacific. (Minneapolis: Minnesota UP., 2010): 96.

[5] Kuniyoshi, Kazuo. Stand! (self-pub., 2015).

[6] Sumartojo, Shanti. “New Geographies of Commemoration.” Progress in Human Geography, vol. 45, no. 3, 2021, pp. 531–547., doi:10.1177/0309132520936758.

[7] “コザ、バー街で黒人暴動. [Black Riot in Koza Bar District].” Ryūkyū Shimpō, 30 August 1969. “金武で黒人兵の発砲騒ぎ. [Black Soldier Fires Gun in Kin Town.]” Ryūkyū Shimpō, 27 August 1969. “ホステス重傷負う: 白人兵になぐられる. [Hostess Receives Serious Injuries: Hit by White Soldier.]” Ryūkyū Shimpō, 4 April 1969. “また米兵のけんか騒ぎ” [Another Raucous Soldier Fight], 19 July 1969 Ryūkyū Shimpō.

_____________________

Image Credits

Koza Uprising © Kuniyoshi Kazuo.

Recommended Citation

Wright, Dustin, Lex McClellan-Ufugusuku, Drew: The 50th Anniversary of the Koza Uprising. In: Public History Weekly 9 (2021) 6, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-18602.

Editorial Responsibility

Copyright © 2021 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 9 (2021) 6

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-18602

Tags: Early Career, Iconography, Japan, Protest, USA

To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

OPEN PEER REVIEW

There’s a lot going on

For a short piece, there is a lot going on in this essay, to the extent that it is unclear to me until deep into it, what the central focus is and even then I’m not entirely certain. If the goal of the essay is to introduce and draw attention to the multiplicity of views and memories on the Koza Uprising, then the article accomplishes that aim by the time the reader reaches its end. But, I think that goal can be achieved more effectively, more efficiently and more clearly with some reorganization and more explicit definition of position and the critical angle/interpretation that flows from it.

The title announces a topic in a straightforward descriptive manner, leaving the definition of a thesis about or interpretative angle on the 50th anniversary of the Koza Uprising to, one would presume, the opening paragraph. That doesn’t explicitly happen here, but I think it has to happen here especially because it is a short essay. The reader—especially the non-specialist reader—needs to know sooner and more directly what the author wants to say about the 50th anniversary of the Koza Uprising, the basis for saying it, and how/why saying it is important.

While I appreciate the dramatic jumping into the story with the quotation from the interview with Kuniyoshi—it’s an interesting, active hook—the following two pages (of four and a half total) drift through material from the interview without a clear announcement of how it fits in a larger argument, mainly because a larger argument hasn’t been articulated. The closest we get lies in paragraphs four and five, where the author poses the question about the formation of Okinawan identity in tension between national and transnational affiliations and invokes the diasporic diffusion of local memories of the Koza Uprising beyond Okinawa. Perhaps those two paragraphs should be reworked a bit into a thesis statement and moved up to start the essay?

But then there is another key aspect of the essay that I think needs clearer articulation earlier on—the author’s position as researcher-commentator and the context for writing of this piece. This comes only in the last paragraph on page three, where the Okinawa Memories Initiative and its Revisiting The Koza Uprising in Global Perspective event is finally mentioned. This suggests to me that perhaps this paragraph should, in some form, lead the essay. The sudden and late mention is a bit befuddling to someone who is unfamiliar with the OMI and this event while the reference to an unidentified “we” and “me” begs the question of who this “we” and “me” are. I think that if the context of the research and writing of this essay is made clear at the beginning along with a definition of theme/angle/thesis, then the articulation of the author’s positionality (which I think is very important here since the essay—in my reading—is about various positions vis-à-vis the Koza Uprising and/or memories of the Koza Uprising, two related but different things) will fall into place. There are hints at the author’s critical position—for example, when referring to 1945-72 Okinawa as a “U.S. military colony,” which is an interpretation, not an objective fact that all observers would agree upon—but I would prefer full open disclosure, not hints, of the author’s writing position. In fact, the academic discourse that has “created” “The Koza Uprising” is indeed another memory-position insofar as it has shaped and reshaped how the event has been framed, defined, discussed, and deployed over time. In sum, the essay reads as if written for the initiated, which could be fine in some arenas, but I’m not so sure if it’s the best for the average non-specialist Public History Weekly reader.

One more thing to consider: tying the “re-discovery” of the Koza Uprising to recent BLM and indigenous activism and invoking past Afro-Okinawan solidarity is not a bad idea, but again, because this is a short piece I wonder if this is the best use of word count. Without being able to further develop these ties, they can appear superficial, or at least the importance of mentioning them in the context of this essay may not be self-evident and fall unappreciated. I leave it to the author and journal editors to decide how to deal with this issue.

This brings me back to my initial observation that “there is a lot going on in this essay” and the question of the essay’s focus. It seems to want to focus on the racial/ethnic question (the author describes the Koza Uprising as “a racialized event”; invokes the Black/White segregation of Koza in the interview with Stan—who I’m guessing is Black but it is not explicitly stated—etc.) but that becomes blurred by non-racial aspects of the transnational question and other positions of memory. Or perhaps it’s the other way around. This is all to say that while there is good material here that introduces the reader to some not-so-obvious perspectives on the evolving history and memory of the Koza Uprising, I hope that material can be more tightly presented to showcase and spotlight the essentials of a well-defined viewpoint that the author wants to convey to readers who may or may not be in the know about the complexities of history, memory, and identity in Okinawa.