Abstract: In the last few years, sound history has developed into a lively field of research within the science of history. Its relationship to public history, however, still seems to be undefined. On the one hand, many formats of public history – from television and radio documentaries through exhibitions up to audio walks and history apps – deliberately rely on auditory forms of representing and conveying history. On the other hand, a systematic analysis of the ways in which the auditory here works as a medium of history, however, still lacks. A particular aspect of this auditory mediation of history lies in the relationship to the past into which we are put, the moment we listen to historical voices.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-14742

Languages: English, German

In the last few years, sound history has developed into a lively field of research within the science of history. Its relationship to public history, however, still seems to be undefined. On the one hand, many formats of public history – from television and radio documentaries through exhibitions up to audio walks and history apps – deliberately rely on auditory forms of representing and conveying history. On the other hand, a systematic analysis of the ways in which the auditory here works as a medium of history, however, still lacks. A particular aspect of this auditory mediation of history lies in the relationship to the past into which we are put, the moment we listen to historical voices.

Voices of the 20th Century

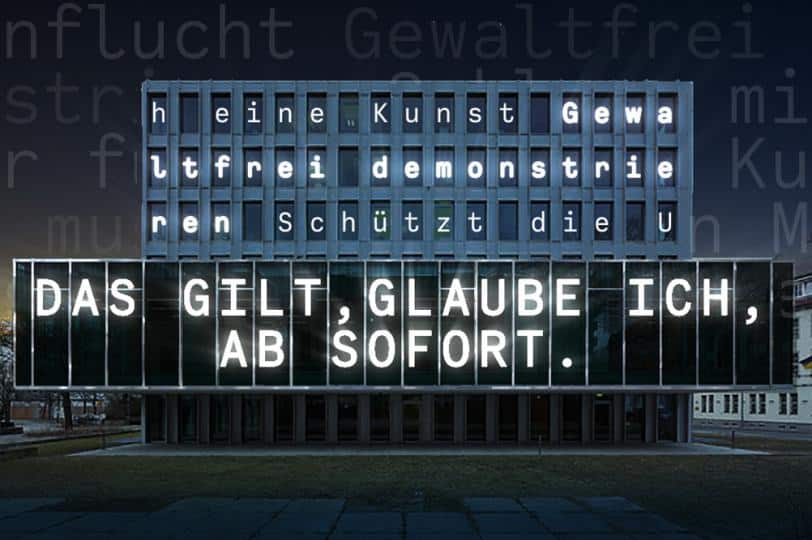

“Das tritt nach meiner Kenntnis, … ist das sofort, unverzüglich.” (To my knowledge, this comes into force, … takes place immediately, right away.) This answer reluctantly uttered by Günter Schabowski in the famous press conference of 9 November 1989 was missing in hardly any of the television or radio documentaries broadcast in the last month about the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. It belongs to the iconic sentences of the 20th century that have entered the auditory collective memory (at least in Germany). Even if one only reads it – even in its changed form in which, on the occasion of the anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, it was projected onto the façade of the Heinrich Böll Foundation – it recalls the voice of Schabowski in our inner ear, the way, slightly hesitantly, it goes up a little when saying “immediately”. It is similar with other famous sentences of the last century, from “Wollt ihr den totalen Krieg?” (Do you want the total war?) through “Ich bin ein Berliner” (I am a Berliner) up to “Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate”. If we read them, then we also hear them.

Thomas Lindenberger years ago pointed out the specific epistemology of contemporary history as an era of audio-visual media: Contemporary history is not only the epoch of those who live at the time, but also the epoch in which this living at the time takes place through mass media, can be recorded in sound and vision and reproduced.[1] Only this recording made it possible that the aforementioned sentences have entered the collective memory in their acoustic shape. Through continual replaying, they shifted from the moment of the medial living at the time into the collective memory so that they trigger the mentioned auditory recognition effect with the future generations as well. This recognition effect is frequently made use of in products of public history these days in order to bring to mind history in auditory terms and to retrieve historical knowledge that is linked with famous sentences.

Auditory Presence Effect

But, where does this specific ability of these vocal testimonies to bring to mind their past come from? Already in the 1960s, the American Jesuit and literary scholar Walter Ong brought forward the argument that a sound, through its fleeting character, conveys presence in a particular way and establishes a personal relation between the listener and what has been heard:

“Sound, bound to the present time by the fact that it exists only at the instant when it is going out of existence, advertises presentness. It heightens presence in the sense of the existential relationship of person to person (I am in your presence; you are present to me), with which our concept of present time (as against past and future) connects: present time is related to us as is a person whose presence we experience. It is ‘here.’ It envelops us. Even the voice of one dead, played from a recording, envelops us with his presence as no picture can.”[2]

Ong’s metaphysics of presence and his concept of orality have been criticized for different reasons which shall not be recapitulated here in detail. The observation of a special ‘presence effect’ of hearing, however, remains untouched thereof.[3] This is, above all, true for hearing a voice and explains the particular fascination for the voices of deceased people which has accompanied the phonography from the very beginning. Already in 1900, the early sound archives started to preserve the voice portraits of famous personalities for posterity.[4] The basic assumption behind this was that personality and character find expression in the human voice, that in the sound of the voice the person as a whole can be recognized, and this in an unmistakable way. If one could replay the voices after the death of their originators, the person as such, as a consequence of this, would be brought to mind once again.

Voice and Person

The wide-ranging assumptions of the voice physiognomy of the early 20th century that closely linked the voice and the character can hardly be maintained anymore these days.[5] But it can still be argued that in the recorded voice a kind of imprint of the person is preserved which transports more of the respective person than, for example, a transcript of what has been said. What is generated by the voice is connected to the body of the originator, to the diaphragm and speech apparatus, and therefore Sybille Krämer speaks of the voice as the “trace of the body in the language”.[6] On the other hand, the voice transports other than physical also emotional states. Tone pitch, speaking rate, speech melody etc. give away something about the emotional mood or, at least, the intended emotional expression of a speaker. We are then again receptive for these physical and emotional parts of the spoken language because the voice is a direct interpersonal means of communication. As a social phenomenon it establishes a relation between the speaker and the person spoken to. We also experience this being spoken to, this character of the voice as “address, appeal and call”[7] in the asymmetrical communication situation with a historical sound document. The historical actors here talk to us in an immediate sense.

The Necessity of Source Criticism

The recognition effect of the famous quotes described at the beginning does not solely rely on this sensual and quasi-social quality of historical voices. The other way around, not everybody feels personally addressed by Günter Schabowski when hearing the famous sentence once more. The prominent role that these sentences play in the medial mediation of history has, however, also to do with the described auditory presence effect. This presence effect might also be deceptive. Since, even if we undoubtedly hear sounds from the past in historical sound documents and when these are thus brought to our mind, the sound documents do not actually, in an unfiltered way, reproduce ‘how it has, in fact, been’ or has sounded, respectively. We much rather deal – as well as with written or visual sources – with specific excerpts of the past which, under very specific conditions, with specific techniques and intentions, were recorded, had a very specific fate of tradition and can be replayed under specific technical conditions today. A critical discussion about the role of historical voices in public history thus also needs a source-critical dealing with historical sound documents.[8]

_____________________

Further Reading

- Morat, Daniel, and Hansjakob Ziemer (Eds.), Handbuch Sound. Geschichte – Begriffe – Ansätze. Stuttgart/Weimar: J. B. Metzler, 2018.

- Paul, Gerhard, and Ralph Schock (Eds.), Sound des Jahrhunderts. Geräusche, Töne, Stimmen 1889 bis heute. Bonn: bpb, 2013.

- The Public Historian, special issue on Sound, Vol. 37, No. 4, 2015.

Web Resources

- Online-Dossier zum Band Sound des Jahrhunderts. Geräusche, Töne, Stimmen 1889 bis heute von Gerhard Paul und Ralph Schock: https://www.bpb.de/geschichte/zeitgeschichte/sound-des-jahrhunderts/ (last accessed 12 November 2019).

- British Library Sounds: https://sounds.bl.uk (last accessed 12 November 2019).

_____________________

[1] Thomas Lindenberger, “Vergangenes Hören und Sehen. Zeitgeschichte und ihre Herausforderung durch die audiovisuellen Medien,” Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History 1, no. 1 (2004): 72-85.

[2] Walter J. Ong, The Presence of the Word. Some Prolegomena for Cultural and Religious History (New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 1967), 101.

[3] Joshua Gunn, “On Recording Performance, or: Speech, the Cry, and the Anxiety of the Fix,” Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies 7, no. 3 (2011): 1–30, 6: “Regardless of the truth or falsity of the attribution of presence to speech, human utterance nevertheless has what we might term ‘presence effects,’ which we respond to in meaningful ways.” Cf. on the term of the effect of presence also Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, Diesseits der Hermeneutik. Die Produktion von Präsenz (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2004).

[4] Jonathan Sterne, The Audible Past. Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction (Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2003), 287-333.

[5] Cf. on these voice-physiognomic assumptions Reinhart Meyer-Kalkus, Stimme und Sprechkünste im 20. Jahrhundert (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 2001).

[6] Sybille Krämer, “Die ‘Rehabilitierung der Stimme’. Über die Oralität hinaus,” Stimme. Annäherung an ein Phänomen, eds. Doris Kolesch und Sybille Krämer (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2006), 269-295, 275.

[7] Ebd., 284.

[8] Cf. Daniel Morat und Thomas Blanck, “Geschichte hören. Zum quellenkritischen Umgang mit historischen Tondokumenten,” Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht 66, no. 11/12 (2015): 703-726. Martin Lücke und Irmgard Zündorf (Hg.), Einführung in die Public History (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2018): 70-74.

_____________________

Image Credits

Ab sofort! © 2019 Julian Jungel, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Recommended Citation

Morat, Daniel: Sound History and Public History. In: Public History Weekly 7 (2019) 30, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-14742.

Translation

Kurt Brügger, swissamericanlanguageexpert, https://www.swissamericanlanguageexpert.ch/.

Editorial Responsibility

Christian Bunnenberg / Peter Gautschi (Team Lucerne)

In den letzten Jahren hat sich die Sound History zu einem lebhaften Forschungsfeld innerhalb der Geschichtswissenschaft entwickelt. Ihr Verhältnis zur Public History scheint jedoch noch unbestimmt. Einerseits setzen viele Formate der Public History – von Fernseh- und Radiodokumentationen über Ausstellungen bis hin zu Audio Walks und Geschichts-Apps – gezielt auf auditive Formen der Geschichtsdarstellung und -vermittlung. Andererseits fehlt es aber noch an einer systematischen Analyse der Arten und Weisen, in denen das Auditive hier als Medium der Geschichte fungiert. Ein besonderer Aspekt dieser auditiven Geschichtsvermittlung liegt in dem Verhältnis, in das uns das Hören historischer Stimmen zur Vergangenheit setzt.

Stimmen des 20. Jahrhunderts

“Das tritt nach meiner Kenntnis, … ist das sofort, unverzüglich.” Die zögernd vorgebrachte Antwort Günter Schabowski in der berühmten Pressekonferenz vom 9. November 1989 fehlte in fast keiner der im letzten Monat ausgestrahlten Fernseh- oder Radiodokumentation zum dreißigsten Jahrestag des Mauerfalls. Sie gehört zu den ikonischen Sätzen des 20. Jahrhunderts, die ins auditive Kollektivgedächtnis (zumindest in Deutschland) eingegangen sind. Selbst wenn man sie nur liest – sogar in der abgewandelten Form, in der sie die Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung anlässlich des Mauerfalljubiläums auf ihre Fassade projiziert hat – ruft das in unserem inneren Ohr die Stimme Schabowskis wieder auf, wie sie, leicht stockend, beim “sofort” etwas nach oben geht. Ähnlich verhält es sich mit anderen berühmten Sätzen des letzten Jahrhunderts, von “Wollt ihr den totalen Krieg” über “Ich bin ein Berliner” bis hin zu “Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate”. Wenn wir sie lesen, dann hören wir sie auch.

Thomas Lindenberger hat vor Jahren auf die spezifische Epistemologie der Zeitgeschichte als Ära der audiovisuellen Medien hingewiesen: Zeitgeschichte ist nicht nur die Epoche der Mitlebenden, sondern auch die Epoche, in der dieses Mitleben massenmedial stattfindet, in Bild und Ton aufgezeichnet und wiedergegeben werden kann.[1] Erst dieses Aufzeichnen hat es ermöglicht, dass die besagten Sätze in ihrer akustischen Gestalt in das kollektive Gedächtnis eingegangen sind. Durch beständiges Wiederabspielen haben sie sich aus dem Moment des medialen Miterlebens in die kollektive Erinnerung verschoben, so dass sie auch bei den Nachgeborenen zu dem angesprochenen auditiven Wiedererkennungseffekt führen. Dieser Wiedererkennungseffekt wird heute vielfach in Produkten der Public History genutzt, um die Geschichte auditiv zu vergegenwärtigen und ein historisches Wissen abzurufen, das mit den berühmten Sätzen verknüpft ist.

Auditiver Präsenzeffekt

Woher aber rührt die besondere Fähigkeit dieser stimmlichen Zeugnisse, ihre Vergangenheit zu vergegenwärtigen? Der amerikanische Jesuit und Literaturwissenschaftler Walter Ong argumentierte schon in den 1960er Jahren, dass der Klang durch seinen flüchtigen Charakter in besonderer Weise Präsenz vermittle und eine persönliche Verbindung zwischen Hörer und Gehörtem herstelle:

“Sound, bound to the present time by the fact that it exists only at the instant when it is going out of existence, advertises presentness. It heightens presence in the sense of the existential relationship of person to person (I am in your presence; you are present to me), with which our concept of present time (as against past and future) connects: present time is related to us as is a person whose presence we experience. It is ‘here.’ It envelops us. Even the voice of one dead, played from a recording, envelops us with his presence as no picture can.”[2]

Ongs Metaphysik der Präsenz und sein Konzept der Oralität sind aus verschiedenen, hier nicht im Einzelnen zu rekapitulierenden Gründen kritisiert worden. Die Beobachtung eines besonderen Präsenzeffekts des Hörens bleibt davon allerdings unberührt.[3] Dies gilt vor allen Dingen für das Hören einer Stimme und begründet zu einem Gutteil die besondere Faszination für die Stimmen Verstorbener, die die Phonographie von Anfang an begleitet hat. Schon um 1900 begannen die frühen Schallarchive, Stimmporträts berühmter Persönlichkeiten für die Nachwelt zu bewahren.[4] Dahinter verbarg sich die Grundannahme, dass Persönlichkeit und Charakter in der menschlichen Stimme zum Ausdruck kommen, dass sich in der Stimmgestalt also die Person als ganze vermittle, und zwar in unverwechselbarer Weise. Konnte man die Stimmen nach dem Tod ihrer Urheber wieder abspielen, so folgerte daraus, würde auch die Person selbst noch einmal gegenwärtig werden.

Stimme und Person

Die weitreichenden Annahmen der Stimmphysiognomik des frühen 20. Jahrhunderts, die Stimme und Charakter eng aneinanderbanden, lassen sich heute kaum noch unterschreiben.[5] Es lässt sich aber noch immer argumentieren, dass sich in der aufgezeichneten Stimme eine Art Abdruck der Person bewahrt, der mehr von ihr transportiert als etwa ein Transkript des von ihr Gesagten. Das hat zum einen mit der körperlichen Dimension der Stimme zu tun. Die Stimmhervorbringung ist an den Körper ihres Urhebers gebunden, an dessen Zwerchfell und Sprechapparat, weshalb Sybille Krämer von der Stimme als der “Spur des Körpers in der Sprache” spricht.[6] Zum anderen transportiert die Stimme neben körperlichen auch emotionale Zustände. Tonhöhe, Sprechgeschwindigkeit, Sprachmelodie usw. verraten etwas über die emotionale Gestimmtheit oder jedenfalls den angestrebten emotionalen Ausdruck einer Sprecherin oder eines Sprechers.

Für diese körperlichen und emotionalen Anteile der gesprochenen Sprache sind wir wiederum empfänglich, weil die Stimme unmittelbares zwischenmenschliches Kommunikationsmittel ist. Als soziales Phänomen stellt sie eine Beziehung zwischen Sprecher*in und An-gesprochenem her. Dieses Angesprochensein, diesen Charakter der Stimme als “Anrede, Appell und Anruf”[7] erleben wir auch in der asymmetrischen Kommunikationssituation mit einem historischen Tondokument. Die historischen Akteur*innen sprechen hier im unmittelbaren Sinn zu uns.

Notwendigkeit der Quellenkritik

Der eingangs geschilderte Wiedererkennungseffekt der berühmten Zitate beruht nicht alleine auf dieser sinnlichen und quasi-sozialen Qualität historischer Stimmen. Umgekehrt fühlt sich nicht jede oder jeder von Günter Schabowski persönlich angesprochen, wenn sie oder er den berühmten Satz wieder hört. Die prominente Rolle, die diese Sätze in der medialen Geschichtsvermittlung spielen, hat aber dennoch mit dem beschriebenen auditiven Präsenzeffekt zu tun. Dieser Präsenzeffekt kann auch trügerisch sein. Denn selbst wenn wir in historischen Tondokumenten unzweifelhaft Klänge aus der Vergangenheit hören und diese uns dadurch gegenwärtig wird, geben die Tondokumente ja nicht ungefiltert wieder, ‘wie es eigentlich gewesen’ ist bzw. geklungen hat. Vielmehr handelt es sich bei ihnen – ebenso wie bei schriftlichen oder bildlichen Quellen – um bestimmte Ausschnitte der Vergangenheit, die unter ganz bestimmten Bedingungen, mit bestimmten Techniken und Intentionen aufgenommen wurden, ein ganz bestimmtes Überlieferungsschicksal hatten und heute unter bestimmten technischen Bedingungen wieder abgespielt werden können. Eine kritische Auseinandersetzung mit der Rolle historischer Stimmen in der Public History bedarf daher auch eines quellenkritischen Umgangs mit historischen Tondokumenten.[8]

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Morat, Daniel, and Hansjakob Ziemer (Eds.), Handbuch Sound. Geschichte – Begriffe – Ansätze. Stuttgart/Weimar: J. B. Metzler, 2018.

- Paul, Gerhard, and Ralph Schock (Eds.), Sound des Jahrhunderts. Geräusche, Töne, Stimmen 1889 bis heute. Bonn: bpb, 2013.

- The Public Historian, special issue on Sound, Vol. 37, No. 4, 2015.

Webressourcen

- Online-Dossier zum Band Sound des Jahrhunderts. Geräusche, Töne, Stimmen 1889 bis heute von Gerhard Paul und Ralph Schock: https://www.bpb.de/geschichte/zeitgeschichte/sound-des-jahrhunderts/ (letzter Zugriff am 12. November 2019).

- British Library Sounds: https://sounds.bl.uk (letzter Zugriff 12. November 2019).

_____________________

[1] Thomas Lindenberger, “Vergangenes Hören und Sehen. Zeitgeschichte und ihre Herausforderung durch die audiovisuellen Medien,” Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History 1, no. 1 (2004): 72-85.

[2] Walter J. Ong, The Presence of the Word. Some Prolegomena for Cultural and Religious History (New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 1967), 101.

[3] Joshua Gunn, “On Recording Performance, or: Speech, the Cry, and the Anxiety of the Fix,” Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies 7, no. 3 (2011): 1–30, 6: “Regardless of the truth or falsity of the attribution of presence to speech, human utterance nevertheless has what we might term ‘presence effects,’ which we respond to in meaningful ways.” Vgl. zum Begriff des Präsenzeffekts auch Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, Diesseits der Hermeneutik. Die Produktion von Präsenz (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2004).

[4] Jonathan Sterne, The Audible Past. Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction (Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2003), 287-333.

[5] Vgl. zu diesen stimmphysiognomischen Annahmen Reinhart Meyer-Kalkus, Stimme und Sprechkünste im 20. Jahrhundert (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 2001).

[6] Sybille Krämer, “Die ‘Rehabilitierung der Stimme’. Über die Oralität hinaus,” Stimme. Annäherung an ein Phänomen, eds. Doris Kolesch und Sybille Krämer (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2006), 269-295, 275.

[7] Ebd., 284.

[8] Vgl. Daniel Morat und Thomas Blanck, “Geschichte hören. Zum quellenkritischen Umgang mit historischen Tondokumenten,” Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht 66, no. 11/12 (2015): 703-726. Martin Lücke und Irmgard Zündorf (Hg.), Einführung in die Public History (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2018): 70-74.

_____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

Ab sofort! © 2019 Julian Jungel, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Morat, Daniel: Sound History und Public History. In: Public History Weekly 7 (2019) 30, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-14742.

Redaktionelle Verantwortung

Christian Bunnenberg / Peter Gautschi (Team Lucerne)

Copyright (c) 2019 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 7 (2019) 30

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-14742