Abstract: As we know, the social role of historians as experts and potential influencers of contemporary debates on account of their knowledge of the past and their critical handling of original sources, is challenged today. In 2015, Jo Guldi and David Armitage deplored this state of affairs in a Manifesto widely commented on worldwide and translated into Italian.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-14196.

Languages: Italiano, English, Deutsch

Come sappiamo, il ruolo sociale degli storici come esperti capaci di influenzare i dibattiti contemporanei a causa della loro conoscenza del passato e delle loro abilità critiche applicate alle fonti originali, è messo in discussione oggi. Questa crisi è ciò che hanno denunciato nel 2015 Jo Guldi e David Armitage in un Manifesto che è stato ampiamente commentato in tutto il mondo e tradotto in italiano.[1]

Promuovere il ruolo della storia nella società

A causa del contesto digitale che inquadra le riflessioni di Armitage e Guldi, anche il Manifeste des Digital Humanities discusso collettivamente nel 2010, cinque anni prima, durante THATCamp Parigi, deve anche essere menzionata qui.[2] La digital (public) history rivisita il campo della storia, rinnovando i modi tradizionali di trattare gli archivi, producendo storiografia accademica e integrando il ruolo del pubblico nel virtuale con pratiche e progetti nel web. La digital (public) history aiuta cosi a modernizzare la professione storica con nuova linfa.

Analogamente allo History Manifesto, il Manifesto italiano della Public History inizia dicendo che la public history vuole rigenerare l’impatto pubblico della storia perché, se il passato è ovunque, la storia che da un senso al passato è spesso assente nei discorsi pubblici.

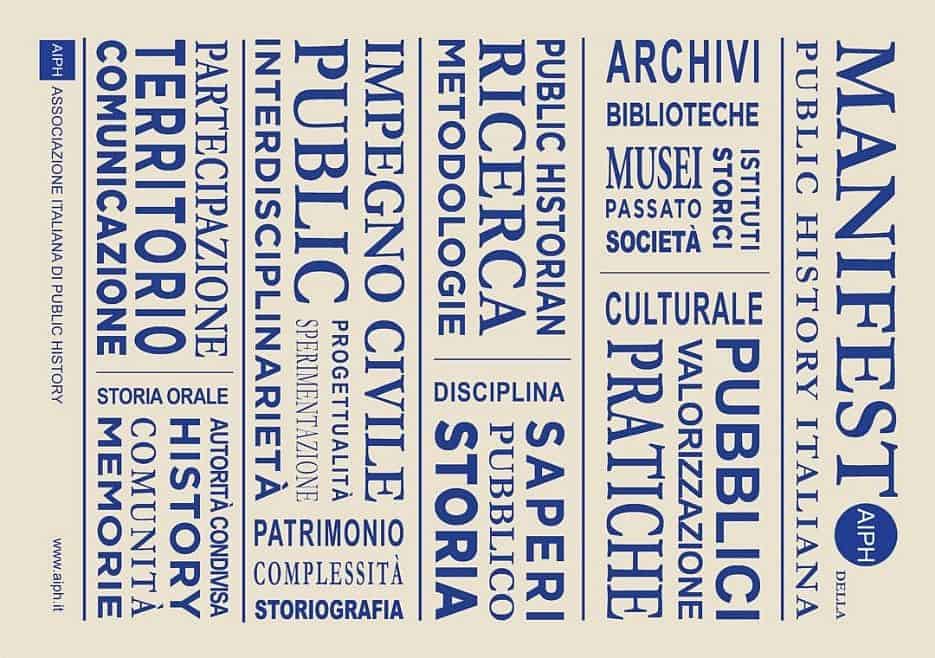

Scritto dai membri del Comitato Direttivo dell’AIPH,[3] il Manifesto della PH italiana, è stato presentato e discusso per la prima volta pubblicamente, durante la conferenza regionale di PH in Piemonte il 7 maggio 2018.[4] Dopo Torino, il progetto è stato ulteriormente discusso dai membri dell’associazione nella lista di discussione dell’AIPH e nel suo gruppo Facebook[5] e, infine, durante la 2a Assemblea annuale dell’AIPH di giugno 2018 a Pisa.[6] Insieme all’originale italiano, l’AIPH ha pubblicato una traduzione inglese del testo finale del Manifesto che incorporava alcuni dei commenti ricevuti in quelle sedi.[7] È stata generata una nuvola di parole (tag cloud) del Manifesto.[8] Le parole chiavi “rivelano” la grande varietà di pratiche di PH nella Penisola.

Chi sono i Public Historian in Italia?

Ma chi sono gli storici pubblici italiani? Gli storici pubblici italiani spesso non conoscono la disciplina; operano nel mercato culturale e nelle istituzioni pubbliche; [9] più recentemente, storici pubblici addestrati sono entrati nel mercato del lavoro delle professioni culturali con un master in storia pubblica o nella comunicazione della storia.[10] In effetti, il Manifesto afferma che è necessario fornire competenze specifiche attraverso “ricerca e l’insegnamento universitario finalizzati alla formazione dei public historian”, preparandoli a diverse professioni nel settore pubblico e privato, principalmente nel turismo del patrimonio e nelle numerose aree coperte dal Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali (MIBAC).[11] Il Manifesto italiano riconosce anche che la storia pubblica promuove e valorizza “ricerche storiche innovative e di qualità i cui risultati sono conseguiti anche grazie a metodologie e pratiche di partecipazione che consentono, talvolta, l’emersione di nuovi documenti”.

Gli storici accademici partecipano a progetti di storia pubblica, come consulenti di curatori in musei e mostre, come esperti nei media o, quando contrastano gli usi strumentali e politici del passato nei media e quando interagiscono con pubblici diversi al di fuori della classe. Eseguono quella che viene chiamata in Italia, la “terza missione”, dopo aver insegnato e fatto ricerche.[12] Se praticata attivamente, la terza missione diventa parte integrante delle attività professionali degli storici accademici che applicano le loro abilità e conoscenze della storia nella società.

La public history aiuta a comprendere pubblicamente il presente

Il Manifesto afferma che, indipendentemente da chi la stia praticando, ciò che è ancora più importante nel fare public history, è l’offerta di competenze professionali al pubblico perché “la storia come sapere critico e le metodologie della ricerca storica sono necessarie anche per la risoluzione di problemi del presente”. Gli storici pubblici condividono i loro metodi storici con il pubblico; nel fare ciò, rafforzano la condivisione di un sapere critico più ampio. Essi rivelano la complessità della storia e insegnano come valutare le fonti del passato nel loro contesto; questa conoscenza critica, applicata all’interno di gruppi e comunità, ha lo scopo di comprendere meglio le radici delle memorie collettive italiane attraverso la pratica dell’autorità condivisa, un metodo vicino a come gli antropologi lavorano con le comunità.[13]

Il Manifesto della Public History contribuisce a costruire una cittadinanza italiana consapevole ed evita i muri e le divisioni tra le comunità, quando queste comunità temono i processi di globalizzazione e di “alterità”. “Le pratiche della public history offrono occasioni e strumenti per la comprensione critica dei contesti storici e dei processi in atto, aiutando ad affrontare la loro complessità”” e “consenta il superamento dei pregiudizi e delle paure che vanno moltiplicandosi nella contemporaneità”. In questo caso, la “Public History è una preziosa risorsa per la coesione sociale favorendo la comprensione e l’incontro fra persone di differente provenienza, di generazioni diverse e con memorie talvolta contrastanti.”

Un percorso italiano verso la Public History

L’ultimo paragrafo del manifesto tratta della specificità di una tradizione italiana di fronte a una disciplina internazionale.[14]

“In Italia, […] sono inoltre imprescindibili per la public history sia la lezione degli storici orali – con le riflessioni sul concetto di “autorità condivisa”, sul valore delle memorie individuali e collettive e sui processi della loro costruzione – sia quella della microstoria, che ha innovato profondamente la storiografia a partire dallo studio di circoscritte realtà territoriali. Infine, non si può dimenticare l’esperienza peculiare dell’Italia nella gestione e valorizzazione di un patrimonio storico, archivistico, artistico, architettonico, paesaggistico e archeologico unico nel mondo.”

È evidente qui che un percorso nazionale italiano verso la PH deriva dalla storia dello sviluppo delle scienze storiche nel paese e dal modo in cui le istituzioni e le pratiche storiche si sono sviluppate dal 19° secolo in poi e, più precisamente, dopo la seconda guerra mondiale.

_____________________

Per approfondire

- Bertucelli, Lorenzo. “La Public History in Italia. Metodologie, pratiche, obiettivi.” In: Public History. Discussioni e pratiche, edited by Paolo Bertella Farnetti, Lorenzo Bertucelli, and Alfonso Botti. 75-96. Milan: Mimesis, 2017.

- Carrattieri, Mirco. “Per una public history italiana.” Italia Contemporanea, n.289, April 2019, 106–121, https://doi.org/10.3280/IC2019-289005.

- Noiret, Serge. “An overview of public history in Italy: No longer a field without a name.” International Public History, 2/1, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1515/iph-2019-0009.

Siti web

- AIPH, The Italian Public History Manifesto (English version), June 2018: https://aiph.hypotheses.org/3193 (ultimo accesso 1 settembre 2019).

- Jo Guldi and David Armitage, The History Manifesto (2014): http://historymanifesto.cambridge.org/historymanifesto_5Feb2015.pdf (ultimo accesso 1 settembre 2019).

- Marin Dacos, Manifesto for the Digital Humanities (2010) (English Translation, March 26, 2011): https://tcp.hypotheses.org/411 (ultimo accesso 1 settembre 2019).

_____________________

[1] Jo Guldi and David Armitage, The History Manifesto (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014) https://historymanifesto.cambridge.org/files/9814/2788/1923/historymanifesto_5Feb2015.pdf (ultimo accesso 1 settembre 2019). Traduzione Italiana, Renato Camurri, Jo Guldi David Armitage: Manifesto per la storia. Il ruolo del passato nel mondo d’oggi, Roma: Donzelli, 2016). Per seguire il dibattito italiano consultare Jo Guldi, David Armitage, “Historians of the world, unite! Tavola rotonda su ‘The History Manifesto,’ Ricerca di Storia Politica, ottobre 13, 2015, http://www.arsp.it/2015/10/13/historians-of-the-world-unite-tavola-rotonda-su-the-history-manifesto-di-jo-guldi-e-david-armitage-2/ (ultimo accesso 1 settembre 2019); “‘The History Manifesto’: a discussion, introduction by Serge Noiret, with contributions by Ramses Delafontaine (ed), Quentin Verreycken, Eric Arnesen,” Memoria e Ricerca, 1/2016, 97–126, DOI: 10.14647/83225;

[2] Marin Dacos, “Manifeste des Digital humanities, à THATCamp Paris, May, 18 and 19, 2010”, http://tcp.hypotheses.org/318

[3] Da allora, nel novembre 2018, il Manifesto è stato adattato per sopportare la propria causa professionale, dai geografi italiani, anche qui, di fronte a una crisi sociale e accademica della loro disciplina. (Manifesto per una “Public Geography”: discutiamone! https://www.ageiweb.it/eventi-e-info-per-newsletter/manifesto-per-una-public-geography-discutiamone/ (ultimo accesso 1 settembre 2019).)

[4] Polo del Novecento https://www.polodel900.it/, program: https://aiph.hypotheses.org/3009 (ultimo accesso 1 settembre 2019).

[5] AIPH, https://www.facebook.com/groups/associazioneitalianapublichistory/ (ultimo accesso 1 settembre 2019).

[6] Metti la storia al lavoro! Seconda Conferenza AIPH, Pisa, June 11–15, 2018, Book of abstracts della Seconda conferenza AIPH di Pisa, https://aiph.hypotheses.org/7389 (ultimo accesso 1 settembre 2019).

[7] Il Manifesto della Public History italiana, https://aiph.hypotheses.org/5442, translated into English as The Italian Public History Manifesto, https://aiph.hypotheses.org/3193 (ultimo accesso 1 settembre 2019).

[8] Voyant-Tools un software creato da Stefan Sinclair e Geoffrey Rockwell è stato utilizzato per creare la nuova di parole (tag cloud), https://voyant-tools.org/ (ultimo accesso 1 settembre 2019).

[9] Il Manifesto menziona che I public historian facilitano l’industria culturale e il turismo attraverso la “la valorizzazione del patrimonio storico, culturale, materiale ed immateriale del paese, in ogni sua forma”.

[10] Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia: Master in Public History http://www.masterpublichistory.unimore.it/site/home.html; Master in Comunicazione Storica all’Università di Bologna, http://www.mastercomunicazionestorica.it/; Master Comunicare la Storia, Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici dell’Università di Roma 3, http://umanistici.lms.uniroma3.it/comunicarelastoria/master; Master in Public History, Fondazione Feltrinelli, Milano, http://www.fondazionefeltrinelli.it/publichistory/ (ultimo accesso 1 settembre 2019).

[11] Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali, http://www.beniculturali.it/mibac/export/MiBAC/index.html#&panel1-1 (ultimo accesso 1 settembre 2019).

[12] “…Con l’introduzione del sistema di Autovalutazione, Valutazione Periodica e Accreditamento (AVA) la Terza Missione viene riconosciuta a tutti gli effetti come una missione istituzionale delle università, accanto all’insegnamento e alla ricerca.”, Agenzia Nazionale di Valutazione del Sistema Universitario e della Ricerca (ANVUR): Terza Missione e Impatto Sociale di Atenei ed Enti di Ricerca, http://www.anvur.it/attivita/temi/ (ultimo accesso 1 settembre 2019).

[13] Francesco Faeta, “Public History, antropologia, fotografia. Immagini e uso pubblico della storia,” Rivista di Studi di Fotografia, N°5, 2017, 52–63, http://dx.doi.org/10.14601/RSF-21199.

[14] Consultare Thomas Cauvin and Serge Noiret, “Internationalizing Public History,” in James B. Gardner and Paola Hamilton (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Public History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 25–43; Thomas Cauvin, Public history: a textbook of practice (New York: Routledge, 2016); Serge Noiret, “A proposito di Public History internazionale e di uso e abuso della storia nei musei,” Memoria e Ricerca, n.1, January–April 2017, 3–20; Thomas Cauvin, “The Rise of Public History: An International Perspective,” Historia Crítica, n.68, 2018, 3–26, https://doi.org/10.7440/histcrit68.2018.01; David Dean and Andreas Etges, “What Is (International) Public History?” International Public History, 1/1, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1515/iph-2018-0007

_____________________

Image Credits

Word Cloud © 2019 AIPH.

Recommended Citation

Noiret, Serge: Il Manifesto della Public History Italiana. In: Public History Weekly 7 (2019) 27, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-14196.

As we know, the social role of historians as experts and potential influencers of contemporary debates on account of their knowledge of the past and their critical handling of original sources, is challenged today. In 2015, Jo Guldi and David Armitage deplored this state of affairs in a Manifesto widely commented on worldwide and translated into Italian.[1]

Fostering the Role of History in Society

The digital context framing Armitage and Guldi’s reflections also requires mentioning the Manifeste des Digital Humanities, discussed five years previously during THATCamp Paris in 2010.[2] Digital (public) history is overhauling the field of history. It revamps traditional ways of dealing with archives and producing academic scholarship, and integrates the public sphere into the virtual realm through web practices and projects. Digital (public) history is also helping to modernize the historical profession with fresh impetus. Similarly to the History Manifesto, an Italian PH Manifesto begins by saying that public history wants to regenerate a public sense of history. It does so because, if the past is everywhere, history that makes sense of the past is often absent from public discourses.

Written by the members of the AIPH Steering Committee, the Italian PH Manifesto[3] was presented and discussed publicly for the first time during the regional PH conference in Piedmont on May 7, 2018.[4] After Turin, the draft was further questioned by members of the AIPH’s mailing list and Facebook group,[5] as well as during the 2nd AIPH Annual Assembly, held in Pisa in June 2018.[6] Together with the Italian original, the AIPH published an English translation of the Manifesto’s final text that incorporated some of the comments received.[7] A topic model (tag cloud) of the Manifesto has since been generated.[8] The tag cloud “reveals” the large variety of PH practices on the Italian Peninsula.

Fostering Public History in Italy

Who are the Italian Public Historians? They often do not know about the discipline, but operate in the cultural market and in public institutions.[9] More recently, trained public historians entered the job market of the cultural professions with a master’s degree in public history or in the communication of history.[10] Indeed, the Manifesto claims the necessity to provide specific skills through “a new university research and teaching area aimed at training public historians.” The idea driving this initiative is to prepare them for different jobs in the public and private sectors, mainly in heritage tourism and in the many areas covered by the Ministry for Heritage and Cultural Activities (MIBAC).[11] The Italian Manifesto also recognizes that Public History promotes and valorizes “innovative and high-quality research, whose results are obtained through participative practices and methodologies that may facilitate the emergence of new documents.”

Academic historians participate in public history projects, as consultants of museum and exhibition curators, as media experts, or by intervening in instrumentalizing and political uses of the past in the media and by interacting with different publics outside the classroom. They perform what is called the “third mission” in Italy, after teaching and researching.[12] When actively practiced, the third mission becomes an integral part of academic historians apply their professional skills and knowledge of history in society.

Publicly Understand the Present

The Manifesto states that, irrespectively of who is practicing it, what matters even more in doing history in public, is providing professional skills to the public because “history as critical knowledge and the methodologies of historical research are necessary for resolving today’s challenges.” Public historians share their historical methods with the public; in doing so, they reinforce wider critical thinking. They disclose the complexity of history and teach how to evaluate sources and evidence of the past in their specific context. This critical knowledge, applied within groups and communities, serves to better understand the roots of Italian collective memories through shared authority, a method close to how anthropologists work with communities.[13]

The Public History Manifesto contributes to building a conscious Italian citizenry and avoids walls and divisions between communities, especially if these fear globalization processes and “otherness.” “Public History practices offer occasions and tools for the critical comprehension of historical contexts and of present processes, helping to confront their complexity.” They also “allow overcoming the fears and prejudices multiplying in the contemporary world.” Thus, “public history is a precious resource for fostering social cohesion, for promoting understanding and encounters among people from different backgrounds and different generations, and sometimes with conflicting memories.”

An Italian path to Public History

The final paragraph of the Manifesto addresses the specificity of an Italian tradition confronted by an international discipline.[14]

“In Italy, […] both the lesson of oral historians—with their reflections on the concept of “shared authority,” on the value of individual and collective memories and on the processes of their construction—and the lesson of microhistory, which has profoundly innovated historiography starting from the study of circumscribed territorial realities, are essential for Public History. Finally, we cannot forget Italy’s unique experience in managing and enhancing its historical, archival and artistic heritage, unique in the world in terms of architecture, landscape and archaeology.”

It is evident here that an Italian national path to PH results from the history and development of the historical sciences in Italy and from how historical institutions and historians’ practices developed from the 19th century onward, and more specifically after World War II.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Bertucelli, Lorenzo. “La Public History in Italia. Metodologie, pratiche, obiettivi.” In: Public History. Discussioni e pratiche, edited by Paolo Bertella Farnetti, Lorenzo Bertucelli, and Alfonso Botti. 75-96. Milan: Mimesis, 2017.

- Carrattieri, Mirco. “Per una public history italiana.” Italia Contemporanea, n.289, April 2019, 106–121, https://doi.org/10.3280/IC2019-289005.

- Noiret, Serge. “An overview of public history in Italy: No longer a field without a name.” International Public History, 2/1, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1515/iph-2019-0009.

Web Resources

- AIPH, The Italian Public History Manifesto (English version), June 2018: https://aiph.hypotheses.org/3193 (last accessed 1 September 2019).

- Jo Guldi and David Armitage, The History Manifesto (2014): http://historymanifesto.cambridge.org/historymanifesto_5Feb2015.pdf (last accessed 1 September 2019).

- Marin Dacos, Manifesto for the Digital Humanities (2010) (English Translation, March 26, 2011): https://tcp.hypotheses.org/411 (last accessed 1 September 2019).

_____________________

[1] Jo Guldi and David Armitage, The History Manifesto (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014) https://historymanifesto.cambridge.org/files/9814/2788/1923/historymanifesto_5Feb2015.pdf (last accessed 1 September 2019). For an Italian version, see Renato Camurri, Jo Guldi David Armitage: Manifesto per la storia. Il ruolo del passato nel mondo d’oggi, Roma: Donzelli, 2016). On the Italian debate, see Jo Guldi, David Armitage, “Historians of the world, unite! Tavola rotonda su ‘The History Manifesto,’ Ricerca di Storia Politica, ottobre 13, 2015, http://www.arsp.it/2015/10/13/historians-of-the-world-unite-tavola-rotonda-su-the-history-manifesto-di-jo-guldi-e-david-armitage-2/ (last accessed 1 September 2019). See also “‘The History Manifesto’: a discussion, introduction by Serge Noiret, with contributions by Ramses Delafontaine (ed), Quentin Verreycken, Eric Arnesen,” Memoria e Ricerca, 1/2016, 97–126, DOI: 10.14647/83225;

[2] Marin Dacos, “Manifeste des Digital humanities, à THATCamp Paris, May, 18 and 19, 2010”, http://tcp.hypotheses.org/318

[3] The Manifesto has since been rewritten (in November 2018) by Italian geographers for their own professional purposes, as their discipline has also faced a social and academic crisis (Manifesto per una “Public Geography”: discutiamone! https://www.ageiweb.it/eventi-e-info-per-newsletter/manifesto-per-una-public-geography-discutiamone/ (last accessed 1 September 2019).)

[4] Polo del Novecento https://www.polodel900.it/, program: https://aiph.hypotheses.org/3009 (last accessed 1 September 2019).

[5] AIPH, https://www.facebook.com/groups/associazioneitalianapublichistory/ (last accessed 1 September 2019).

[6] Metti la storia al lavoro! Seconda Conferenza AIPH, Pisa, June 11–15, 2018, Book of abstracts della Seconda conferenza AIPH di Pisa, https://aiph.hypotheses.org/7389 (last accessed 1 September 2019).

[7] Il Manifesto della Public History italiana, https://aiph.hypotheses.org/5442, translated into English as The Italian Public History Manifesto, https://aiph.hypotheses.org/3193 (last accessed 1 September 2019).

[8] Stefan Sinclair and Geoffrey Rockwell’s Voyant-Tools was used to create the tag cloud: https://voyant-tools.org/ (last accessed 1 September 2019).

[9] The Manifesto mentions that public historians foster the cultural industry and tourism, by “promoting Italy’s historical, material and immaterial cultural heritage, in all its forms”.

[10] University of Modena and Reggio Emilia: Master in Public History http://www.masterpublichistory.unimore.it/site/home.html; Master’s program in the communication of history (Master in Comunicazione Storica) at the University of Bologna, http://www.mastercomunicazionestorica.it/; Master Comunicare la Storia, Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici dell’Università di Roma 3, http://umanistici.lms.uniroma3.it/comunicarelastoria/master; Master in Public History, Fondazione Feltrinelli, Milano, http://www.fondazionefeltrinelli.it/publichistory/ (last accessed 1 September 2019).

[11] Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali, http://www.beniculturali.it/mibac/export/MiBAC/index.html#&panel1-1 (last accessed 1 September 2019).

[12] “…with the introduction of the Self-Assessment, Periodic Evaluation and Accreditation (AVA) system, the Third Mission is recognized to all effects as an institutional mission of universities, alongside teaching and research,” Agenzia Nazionale di Valutazione del Sistema Universitario e della Ricerca (ANVUR): Terza Missione e Impatto Sociale di Atenei ed Enti di Ricerca, http://www.anvur.it/attivita/temi/ (last accessed 1 September 2019).

[13] Francesco Faeta, “Public History, antropologia, fotografia. Immagini e uso pubblico della storia,” Rivista di Studi di Fotografia, N°5, 2017, 52–63, http://dx.doi.org/10.14601/RSF-21199.

[14] See Thomas Cauvin and Serge Noiret, “Internationalizing Public History,” in James B. Gardner and Paola Hamilton (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Public History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 25–43; Thomas Cauvin, Public history: a textbook of practice (New York: Routledge, 2016); Serge Noiret, “A proposito di Public History internazionale e di uso e abuso della storia nei musei,” Memoria e Ricerca, n.1, January–April 2017, 3–20; Thomas Cauvin, “The Rise of Public History: An International Perspective,” Historia Crítica, n.68, 2018, 3–26, https://doi.org/10.7440/histcrit68.2018.01; David Dean and Andreas Etges, “What Is (International) Public History?” International Public History, 1/1, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1515/iph-2018-0007

_____________________

Image Credits

Word Cloud © 2019 AIPH.

Recommended Citation

Noiret, Serge: The Italian Public History Manifesto. In: Public History Weekly 7 (2019) 27, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-14196.

Wie wir wissen, wird die soziale Rolle der Historiker*innen als Expert*innen und ihr potenzieller Einfluss auf zeitgenössische Debatten aufgrund ihres Wissens über die Vergangenheit und ihres kritischen Umgangs mit Quellen heute in Frage gestellt. Jo Guldi und David Armitage haben 2015 diesen Missstand in einem Manifest angeprangert, das weltweit Beachtung gefunden hat und seither ins Italienische übersetzt worden ist.[1]

Die gesellschaftliche Rolle der Geschichte fördern

Aufgrund des digitalen Kontextes, in dem Armitage und Guldis Überlegungen angesiedelt sind, muss auch das Manifeste des Digital Humanities, das fünf Jahre zuvor während des THATCamp Paris im Jahr 2010 diskutiert wurde, hier erwähnt werden.[2] Die digitale (öffentliche) Geschichte ist dabei, die Geschichtswissenschaft gründlich zu verändern. Sie erneuert den traditionellen Umgang mit Archiven und die Produktion wissenschaftlicher Forschung und integriert die Rolle der Öffentlichkeit in den virtuellen Raum durch Webpraktiken und Projekte. Die digitale (öffentliche) Geschichte bringt frischen Wind in die Modernisierung der historischen Profession. Ähnlich wie das History Manifesto beginnt das italienische Public-History-Manifest damit, dass Public History den öffentlichen Sinn für Geschichte regenerieren will. Denn wenn die Vergangenheit überall ist, fehlt in den öffentlichen Diskursen oft jene Geschichte, die den Sinn der Vergangenheit zu verstehen sucht.

Das von den Mitgliedern des AIPH-Lenkungsausschusses verfasste italienische PH-Manifest[3] wurde auf der regionalen PH-Konferenz am 7. Mai 2018 im Piemont erstmals öffentlich vorgestellt und diskutiert.[4] Nach Turin wurde der Entwurf von den Mitgliedern des Vereins in der AIPH-Mailingliste und Facebook-Gruppe veröffentlicht[5] und am 2. Juni 2018 in Pisa zur weiteren Diskussion gestellt. Gemeinsam mit dem italienischen Original veröffentlichte die AIPH eine englische Übersetzung der endgültigen Fassung des Manifests, einschliesslich einige der erhaltenen Kommentare.[7] Darauf wurde ein Themenmodell (Tagcloud) des Manifests erstellt.[8] Die Tagcloud “offenbart” die große Vielfalt der PH-Praktiken auf der italienischen Halbinsel.

Förderung von Public History in Italien

Doch wer genau sind die italienischen Public Historians? Oft wissen sie nichts über ihre Disziplin; sie agieren auf dem Kulturmarkt und in öffentlichen Institutionen.[9] In jüngster Zeit sind ausgebildete Public Historians (mit einem Masterabschluss in Public History oder in der Vermittlung von Geschichte) in den Kulturarbeitsmarkt eingestiegen. [10] Das Manifest behauptet nämlich, dass es notwendig sei, spezifische Fähigkeiten durch “einen neuen universitären Forschungs- und Lehrbereich, der auf die Bildung von Historiker*innen abzielt”, bereitzustellen und Absolvent*innen auf verschiedene Tätigkeiten im öffentlichen und privaten Sektor vorzubereiten, vor allem im Bereich des Kulturtourismus und in den vielen Bereichen, die vom Ministerium für Kulturerbe und kulturelle Aktivitäten (MIBAC) abgedeckt werden. [11] Das italienische Manifest anerkennt auch, dass Public History “innovative und qualitativ hochwertige Forschungen fördert und aufwertet, deren Ergebnisse durch partizipative Praktiken und Methoden erzielt werden, die die Entstehung neuer Dokumente fördern könnte.”

Akademische Historiker*innen beteiligen sich an Public-History-Projekten, sind tätig als Berater*innen von Kurator*innen in Museen und Ausstellungen, sowie als Expert*innen in den Medien, oder indem sie instrumentalisierende und politische Verwendungen der Vergangenheit durch die Medien vereiteln und sich mit verschiedenen Öffentlichkeiten ausserhalb der Lehre auseinandersetzen. Sie erfüllen das, was in Italien als “dritte Mission” bezeichnet wird, nach Lehre und Forschung.[12] Wenn sie aktiv praktiziert wird, wird die dritte Mission zu einem integralen Bestandteil der professionellen Tätigkeit von akademischen Historiker*innen, die ihre Fähigkeiten und ihr Wissen über Geschichte in die Gesellschaft einbringen und dort anwenden.

Die Gegenwart öffentlich verstehen

Das Manifest besagt, dass unabhängig davon, wer öffentliche Geschichtsschreibung praktiziert, die Vermittlung von Fachkompetenz an die Öffentlichkeit noch wichtiger ist, denn “Geschichte als kritisches Wissen und die Methoden der Geschichtsforschung sind für die Lösung heutiger Probleme notwendig”. Public Historians teilen ihre historischen Methoden mit der Öffentlichkeit und verstärken dadurch ein breiteres kritisches Denken. Sie legen die Komplexität der Geschichte frei und zeigen, wie man Quellen und Zeugnisse der Vergangenheit in ihrem Kontext bewertet; dieses kritische Wissen, in Gruppen und Gemeinschaften angewendet, dient dem Zweck, die Wurzeln des italienischen kollektiven Gedächtnisses durch “Shared Authority”, eine Methode, die der Arbeitsweise von Anthropolog*innen mit menschlichen Gemeinschaften nahe kommt, besser zu verstehen[13].

Das Public History Manifesto trägt zum Aufbau einer bewussten italienischen Öffentlichkeit bei und vermeidet Mauern und Spaltungen zwischen den Gemeinschaften, besonders dann, wenn diese sich vor Globalisierungsprozessen und “dem Anderen” fürchten. “Die Praktiken von Public History bieten Anlässe und Werkzeuge für das kritische Verständnis historischer Kontexte und gegenwärtiger Prozesse, die helfen, ihre Komplexität zu bewältigen”. Desweitern “erlauben sie es, Ängste und Vorurteile zu überwinden, die sich in der heutigen Welt vermehren”. Und: “Public History ist eine wertvolle Ressource für den sozialen Zusammenhalt, die das Verständnis und die Begegnung zwischen Menschen unterschiedlicher Herkunft, verschiedener Generationen und mit manchmal widersprüchlichen Erinnerungen fördert”.

Ein italienischer Weg zur Public History

Der letzte Absatz des Manifests befasst sich mit der Besonderheit der italienischen Tradition, die sich mit einer internationalen Disziplin konfrontiert sieht [14].

“In Italien sind sowohl die Lehre der Oral Historians – mit ihren Überlegungen zum Konzept der ‘geteilten Autorität’, zum Wert individueller und kollektiver Erinnerungen und zu den Prozessen ihrer Konstruktion – als auch die Lehre der Mikrogeschichte, die die Geschichtsschreibung ausgehend vom Studium umschriebener territorialer Realitäten grundlegend erneuert hat, für die Public History von wesentlicher Bedeutung. Schliesslich dürfen wir die einzigartige Erfahrung Italiens bei der Verwaltung und Aufwertung seines historischen, archivarischen und künstlerischen Erbes nicht vergessen, das in Bezug auf Architektur, Landschaft und Archäologie weltweit einzigartig ist”.

Hier zeigt sich, dass sich ein spezifisch italienischer Weg zur PH aus der Entwicklung der Geschichtswissenschaften in Italien sowie aus der Entwicklung der historischen Institutionen und Praktiken der Historiker*innen ab dem 19. Jahrhundert und insbesondere nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg ergibt.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Bertucelli, Lorenzo. “La Public History in Italia. Metodologie, pratiche, obiettivi.” In: Public History. Discussioni e pratiche, edited by Paolo Bertella Farnetti, Lorenzo Bertucelli, and Alfonso Botti. 75-96. Milan: Mimesis, 2017.

- Carrattieri, Mirco. “Per una public history italiana.” Italia Contemporanea, n.289, April 2019, 106–121, https://doi.org/10.3280/IC2019-289005.

- Noiret, Serge. “An overview of public history in Italy: No longer a field without a name.” International Public History, 2/1, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1515/iph-2019-0009.

Webressourcen

- AIPH, The Italian Public History Manifesto (English version), June 2018: https://aiph.hypotheses.org/3193 (letzter Zugriff 1. September 2019).

- Jo Guldi and David Armitage, The History Manifesto (2014): http://historymanifesto.cambridge.org/historymanifesto_5Feb2015.pdf (letzter Zugriff 1. September 2019).

- Marin Dacos, Manifesto for the Digital Humanities (2010) (English Translation, March 26, 2011): https://tcp.hypotheses.org/411 (letzter Zugriff 1. September 2019).

_____________________

[1] Jo Guldi and David Armitage, The History Manifesto (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014) https://historymanifesto.cambridge.org/files/9814/2788/1923/historymanifesto_5Feb2015.pdf (letzter Zugriff 1. September 2019). Für die italienische Fassung, siehe Renato Camurri, Jo Guldi David Armitage: Manifesto per la storia. Il ruolo del passato nel mondo d’oggi, Roma: Donzelli, 2016). Zur italienischen Debatte siehe Jo Guldi, David Armitage, “Historians of the world, unite! Tavola rotonda su ‘The History Manifesto,’ Ricerca di Storia Politica, ottobre 13, 2015, http://www.arsp.it/2015/10/13/historians-of-the-world-unite-tavola-rotonda-su-the-history-manifesto-di-jo-guldi-e-david-armitage-2/ (letzter Zugriff 1. September 2019). Vgl. auch “‘The History Manifesto’: a discussion, introduction by Serge Noiret, with contributions by Ramses Delafontaine (ed), Quentin Verreycken, Eric Arnesen,” Memoria e Ricerca, 1/2016, 97–126, DOI: 10.14647/83225;

[2] Marin Dacos, “Manifeste des Digital humanities, à THATCamp Paris, May, 18 and 19, 2010”, http://tcp.hypotheses.org/318

[3] Im November 2018 haben italienische Geograf*innen das Manifest für ihre eigene Disziplin, die sich in einer gesellschaftlichen wie wissenschaftlichen Krise befindet, neu verfasst (Manifesto per una “Public Geography”: discutiamone! https://www.ageiweb.it/eventi-e-info-per-newsletter/manifesto-per-una-public-geography-discutiamone/ (letzter Zugriff 1. September 2019).)

[4] Polo del Novecento https://www.polodel900.it/, program: https://aiph.hypotheses.org/3009 (letzter Zugriff 1. September 2019).

[5] AIPH, https://www.facebook.com/groups/associazioneitalianapublichistory/ (letzter Zugriff 1. September 2019).

[6] Metti la storia al lavoro! Seconda Conferenza AIPH, Pisa, June 11–15, 2018, Book of abstracts della Seconda conferenza AIPH di Pisa, https://aiph.hypotheses.org/7389 (letzter Zugriff 1. September 2019).

[7] Il Manifesto della Public History italiana, https://aiph.hypotheses.org/5442, translated into English as The Italian Public History Manifesto, https://aiph.hypotheses.org/3193 (letzter Zugriff 1. September 2019).

[8] Stefan Sinclair and Geoffrey Rockwell’s Voyant-Tools was used to create the tag cloud: https://voyant-tools.org/ (letzter Zugriff 1. September 2019).

[9] The Manifesto mentions that public historians foster the cultural industry and tourism, by “promoting Italy’s historical, material and immaterial cultural heritage, in all its forms”.

[10] University of Modena and Reggio Emilia: Master in Public History http://www.masterpublichistory.unimore.it/site/home.html; Master’s program in the communication of history (Master in Comunicazione Storica) at the University of Bologna, http://www.mastercomunicazionestorica.it/; Master Comunicare la Storia, Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici dell’Università di Roma 3, http://umanistici.lms.uniroma3.it/comunicarelastoria/master; Master in Public History, Fondazione Feltrinelli, Milano, http://www.fondazionefeltrinelli.it/publichistory/ (letzter Zugriff 1. September 2019).

[11] Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali, http://www.beniculturali.it/mibac/export/MiBAC/index.html#&panel1-1 (letzter Zugriff 1. September 2019).

[12] “…with the introduction of the Self-Assessment, Periodic Evaluation and Accreditation (AVA) system, the Third Mission is recognized to all effects as an institutional mission of universities, alongside teaching and research,” Agenzia Nazionale di Valutazione del Sistema Universitario e della Ricerca (ANVUR): Terza Missione e Impatto Sociale di Atenei ed Enti di Ricerca, http://www.anvur.it/attivita/temi/ (letzter Zugriff 1. September 2019).

[13] Francesco Faeta, “Public History, antropologia, fotografia. Immagini e uso pubblico della storia,” Rivista di Studi di Fotografia, N°5, 2017, 52–63, http://dx.doi.org/10.14601/RSF-21199.

[14] See Thomas Cauvin and Serge Noiret, “Internationalizing Public History,” in James B. Gardner and Paola Hamilton (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Public History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 25–43; Thomas Cauvin, Public history: a textbook of practice (New York: Routledge, 2016); Serge Noiret, “A proposito di Public History internazionale e di uso e abuso della storia nei musei,” Memoria e Ricerca, n.1, January–April 2017, 3–20; Thomas Cauvin, “The Rise of Public History: An International Perspective,” Historia Crítica, n.68, 2018, 3–26, https://doi.org/10.7440/histcrit68.2018.01; David Dean and Andreas Etges, “What Is (International) Public History?” International Public History, 1/1, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1515/iph-2018-0007

_____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

Word Cloud © 2019 AIPH.

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Noiret, Serge: The Italian Public History Manifesto. In: Public History Weekly 7 (2019) 27, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-14196.

Copyright (c) 2019 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 7 (2019) 27

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-14196

Tags: Italy (Italien), Language: Italian, Public History, Science Communication (Wissenschaftskommunikation), Speakerscorner