Abstract: The sesquicentennial celebrations of Canadian Confederation in 2017 provide a unique opportunity to reflect on the history of the country, to look at where Canadians have been and where they are headed.[1] All things considered, do Canadians think that things have improved over the last 150 years? There is no consensus amongst the population. Part of the challenge rests on how we, as historical beings, evaluate progress – that is to say, our judgement on the direction of change. As with the notion of civilization recently discussed by Peter Seixas, the concept of “progress” is a contested one.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-11329.

Languages: Français, English, Deutsch

Les célébrations entourant le 150e anniversaire de la Confédération canadienne en 2017 offre une opportunité de réfléchir sur l’histoire du Canada, de regarder le chemin parcouru ainsi que les passages qui s’offrent à nous. Dans l’ensemble, les Canadiens pensent-ils que les choses se sont améliorées au cours des 150 dernières années? Il n’existe pas de consensus au sein de la population sur cette question. L’une des raisons est liée à notre capacité à évaluer le progrès — notre jugement quant à la direction empruntée par le changement. Comme pour la notion de civilisation discutée par Peter Seixas, le concept de « progrès » est tout aussi contesté.[1]

Le besoin de perspective historique

Pour répondre à ma question initiale, nous devons faire appel à la perspective historique. En effet, il nous est impossible de poser un jugement critique sur la direction du changement historique sans avoir au préalable placer les événements dans un contexte temporel qui oriente notre analyse dans la durée. La perspective historique est, pour les fins de mon propos, synonyme de « grand tableau » schématique de l’histoire, une vue du changement pris dans son ensemble. De manière générale, les didacticiens se sont intéressés à la perspective historique comme outil d’analyse permettant d’examiner le passé en se fiant aux conditions particulières d’une époque différente de la nôtre. Mais il existe une autre façon de concevoir la perspective historique à titre d’habileté à comprendre les expériences humaines dans un contexte temporel qui permet l’articulation du passé avec le présent et l’avenir possible, offrant ainsi un sens au temps dans la durée. En termes narratifs, c’est grâce à la perspective historique que les historiens peuvent mettre en récit le passé sous la forme d’une synthèse de l’expérience humaine. C’est également par la perspective historique que nous pouvons orienter nos actions dans le temps, en étant conscient d’un horizon d’attente qui informe la lecture que nous faisons du passé.[2]

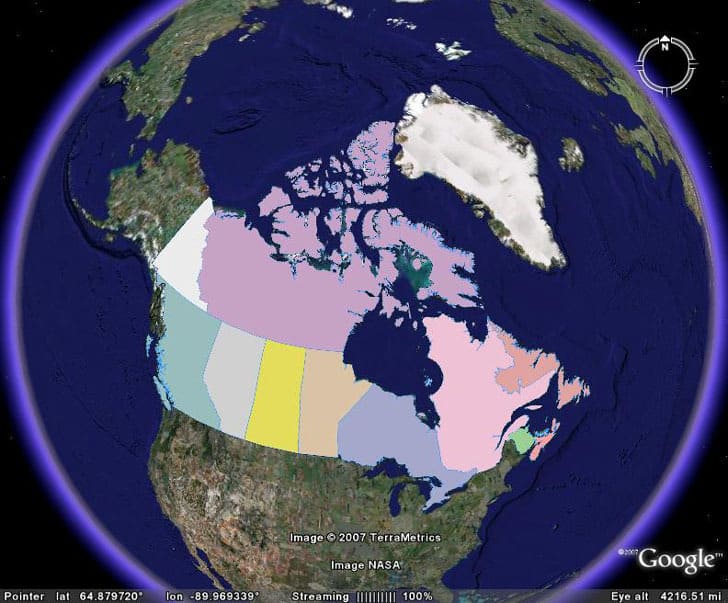

Denis Shemilt soutient que différents grands tableaux de l’histoire peuvent être développés autour de sphères de l’activité humaine qui offrent une vision synoptique du changement.[3] Si l’on utilise Google comme analogie, on pourrait dire que les grands tableaux nous permettent de concevoir l’histoire tout comme Google Earth nous fait voir la terre grâce aux outils de focalisation qui permettent un « zoom » sur des villes ou des monuments tout en étant capable de revenir à une vue globale. Évidemment, à ce niveau de résolution planétaire, il nous est impossible de saisir les particularités de notre environnement mais nous pouvons néanmoins apprécier le contexte au sein duquel s’opèrent les changements climatiques, la formation des nuages ou la pollution océanique. En termes concrets, les villes et les rivières sont les personnages et les événements alors que les continents, les nuages et les océans sont en quelque sorte les phénomènes sociaux associés à ce que Fernand Braudel appelait la longue durée de l’histoire.

Les grands tableaux de l’histoire canadienne

Regardons de plus près ce à quoi peut correspondre l’usage de grands tableaux dans le contexte canadien. Évidement, pour avoir une vue d’ensemble du développement, un recul de 10 ans, 20 ans ou même 25 ans n’est pas suffisant. Il nous faut davantage de perspective pour apprécier le changement dans la durée.[4]

La richesse collective est un tableau d’analyse intéressant. A titre de membre du G7, le Canada est un pays relativement riche avec une économie du savoir axée sur les services et qui, à l’origine, était fondée sur l’agriculture. Au moment de la Confédération, le PIB par habitant était de 1451$ (en dollar US contant de 1990).[5] Le budget total du gouvernement canadien était de 14 millions $, avec un ratio de dépense-PIB d’approximativement 5%. Dans les années 2010, le PIB par habitant a atteint 24 941$ (en dollar US constant de 1990). En terme budgétaire, les dépenses gouvernementales canadiennes pour 2017 seront d’environ 331 milliards de dollars (CDN) avec un ratio de dépense-PIB de 15,6%. Ces données globales indiquent que le Canada est un pays nettement plus riche qu’il l’était il y a 150 ans avec des investissements beaucoup plus grands dans les programmes et les services. Une partie importante de ces changements socioéconomiques est survenue après la Seconde Guerre mondiale alors que le Canada a choisi de jouer un rôle plus actif dans l’économie de manière à offrir une meilleure redistribution des richesses par l’état providence.

Si l’on analyse la situation de plus près, on réalise que ce ne sont pas toutes les régions ni tous les citoyens canadiens qui ont su bénéficier de cette richesse. Alors que le taux de pauvreté absolu (basé sur la consommation alimentaire minimale) est relativement bas (8,8%), ce taux est nettement plus élevé chez certains groupes, notamment les Autochtones. Selon le Centre canadien de politiques alternatives, la moitié des jeunes Autochtones vivent dans la pauvreté, un chiffre qui grimpe à 66% dans les provinces du Manitoba et de la Saskatchewan.[6] L’étude indique également que les enfants dans les réserves sont ceux qui font face aux pires situations socioéconomiques, vivant souvent dans des maisons décrépites et sans eau potable.

Le problème du morcellement du savoir

Les élèves canadiens apprennent l’histoire de manière cumulative, d’année en année. Selon cette logique, les jeunes auront progressivement accès à l’ensemble de l’histoire canadienne au cours de leurs études. Malheureusement, les programmes scolaires et les évaluations ministérielles qui les accompagnent sont élaborés de manière séquentielle, d’étape en étape, de module en module, comme si nous pouvions traiter l’histoire nationale comme un saucisson que l’on couperait en petites tranches comestibles pour les jeunes.

Le résultat de ce morcellement du savoir est néfaste. Les jeunes terminent leur cursus scolaire sans véritable tableau d’ensemble de l’histoire nationale expliquée selon des phénomènes sociaux tels que la richesse collective, la littératie, les conditions de vie et la citoyenneté. Tout aussi problématique est le fait que peu d’entre eux comprennent comment le passé affecte le présent et oriente leur choix de vie. La réponse suivante d’un élève de 12e année est typique : « Je ne me souviens pas grand chose de ce que j’ai appris en histoire ».

Ce que je propose ici est une vision différente de la perspective historique. Nous devons (ré)imaginer l’histoire comme un objet d’étude dynamique que nous pouvons analyser à différents niveaux de résolution et à partir de données probantes qui nous permettent de mieux comprendre des phénomènes de plus vastes envergures. Les citoyens peuvent évaluer le progrès/déclin de leur société uniquement s’ils ont les outils et les tableaux d’analyse leur donnant une vue d’ensemble du changement dans la durée. Ces tableaux, comme nous le rappelle Shemilt, sont provisoires dans la mesure où ils servent de structures schématiques à partir desquelles il devient possible d’analyser le passé à différents niveaux de résolution. Au final, les jeunes doivent comprendre que les grands tableaux sont des heuristiques utiles à l’interprétation et à la généralisation. Ils doivent également prendre conscience du fait que leur position dans l’histoire joue un rôle critique puisqu’elle s’inscrit dans un contexte social et détermine leur rapport au passé.

_____________________

Lectures supplémentaires

- Roser, Max. “The short history of global living conditions and why it matters that we know it.” Our World In Data. Février 2018. https://ourworldindata.org/a-history-of-global-living-conditions-in-5-charts (consulté pour la dernière fois le 22 février 2018).

- Shemilt, Denis. “Drinking an Ocean and Pissing a Cupful.” In National History Standards: The Problem of the Canon and the Future of Teaching History, edited by Linda Symcox and Arie Wilschut, 141-210. Charlotte NC: Information Age Publishing, 2009.

Resources sur le web

- OECD special project. “How was life?” http://www.oecd.org/statistics/how-was-life-9789264214262-en.htm (consulté pour la dernière fois le 22 février 2018).

- Outils de géographie gratuits: http://freegeographytools.com/2007/colored-countrysubdivision-google-earth-polygons-with-color-your-map (consulté pour la dernière fois le 22 février 2018).

_____________________

[1] Peter Seixas, “Culture, civilization and historical consciousness,” Public History Weekly 5 (2017): 41, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10620 (consulté pour la dernière fois le 8 février 2018). Sur la notion de progress, voir mon ouvrage: Stéphane Lévesque, Thinking Historically: Educating Students for the 21st century (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008), chap. 5.

[2] Jörn Rüsen, History: Narration, Interpretation, Orientation (New York: Berghahn Books, 2005).

[3] Denis Shemilt, “Drinking an Ocean and Pissing a Cupful,” dans National History Standards: The Problem of the Canon and the Future of Teaching History, ed. Linda Symcox et Arie Wilschut (Charlotte NC: Information Age Publishing, 2009), 141-210.

[4] Pour une analyse historique des conditions de vie en Occident, voir Max Roser, “The short history of global living conditions and why it matters that we know it,” Our World In Data, https://ourworldindata.org/a-history-of-global-living-conditions-in-5-charts (consulté pour la dernière fois le 8 février 2018).

[5] William Watson, “Look at how Canadians lived 150 years ago and be very, very grateful,” Financial Post, 29 Juin 2017, http://business.financialpost.com/opinion/william-watson-look-at-how-canadians-lived-150-years-ago-and-be-very-very-grateful (consulté pour la dernière fois le 8 février 2018). Pour une analyse détaillée des conditions économiques et de vie de divers pays depuis le 19e siècle, voir le projet de l’OCDE intitulé: “How was life?” disponible en ligne http://www.oecd.org/statistics/how-was-life-9789264214262-en.htm (consulté pour la dernière fois le 8 février 2018).

[6] David Macdonald et Daniel Wilson, “Poverty or Prosperity: Indigenous children in Canada,” Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, 19 Juin 2013, https://www.policyalternatives.ca/publications/reports/poverty-or-prosperity (consulté pour la dernière fois le 8 février 2018).

_____________________

Crédits illustration

Image NASA © TerraMetrics Google

Citation recommandée

Lévesque, Stéphane: Les choses vont-elles en s’améliorant ou non? Comment voir les “grands tableaux” de l’histoire canadienne. In: Public History Weekly 6 (2018) 8, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-11329.

The sesquicentennial celebrations of Canadian Confederation in 2017 provide a unique opportunity to reflect on the history of the country, to look at where Canadians have been and where they are headed.[1] All things considered, do Canadians think that things have improved over the last 150 years? There is no consensus amongst the population. Part of the challenge rests on how we, as historical beings, evaluate progress – that is to say, our judgement on the direction of change. As with the notion of civilization recently discussed by Peter Seixas, the concept of “progress” is a contested one.[2]

The Need for Historical Perspective

In order to answer my initial question, historical perspective is necessary. We cannot provide a sound judgment on the direction of change in national history unless we can place events in a temporal context of Canadian development. Historical perspective is, at least for the purpose of my argument, tantamount to “big picture” history. Typically, history educators have referred to historical perspective as the ability to understand the difference between past and present, that is to say between the lives of predecessors and our modern way of life. However, there is another interpretation: the ability to construe human experiences and changes in a temporal whole that bridges both the past with the present and our expected future with a concept of continuity. It is through historical perspective that we create stories centering on our practical life in the present by means of interpreting past actions.[3]

Denis Shemilt claims that different big-picture frameworks can be developed around areas of human activity that offer a synoptic perspective on the present by means of taking the long view of what happened in human affairs.[4] To use a Google analogy, big picture frameworks allow us to look at history in the way that we view our planet via Google Earth, zooming in to see key places in very sharp detail, but also zooming out to see entire continents or even the Earth.[5] At this great distance, it is impossible for the naked eye to observe geographical features such as rivers or cities. However, we can certainly appreciate the larger context in which global phenomena such as cloud formation, pollution, and global warming take place. The historical equivalent of rivers and cities are historical characters and great events while the continents, clouds, and oceans are societal aspects (such as mode of production, political organization, culture, etc.) of what Fernand Braudel once called the longue durée of history.

Big Picture Frameworks in Canadian History

Let us consider Canadian history from a big-picture framework in order to grasp what all this might look like. Of course, to obtain a bigger perspective on the historical development of Canada, ten, twenty, or even twenty-five years may not be enough. We need to consider a much longer-term perspective to appreciate change over time.[6]

Collective wealth is one such analytical framework. As a member of the G7, Canada is a relatively rich country with an economic structure moving from rural agricultural to a modern, highly urbanized, service-intensive economy. At the dawn of Confederation, Canada’s per capita GDP was $1,451 (in constant 1990 US$).[7] The federal government had a budget of $14 million (CDN$) – an expenditure to GDP ratio of approximately 5%. By the 2010s, per capita GDP had reached $24,941 (in constant 1990 US$). In terms of budget, it is anticipated that by the end of 2017 total federal government spending will be $331 billion (CDN$) with an expenditure to GDP ratio of about 15.6%. What this means is that Canada is much richer than 150 years ago and that it invests significantly more in programs and services than it did in 1867. While these changes started long ago, they accelerated after World War II with the rapid industrialization of Canada. This also coincided with greater involvement of the state in the economy, which aimed to bring about a more egalitarian society via redistribution – the welfare state.

When we zoom in on particular regions and populations, however, we realize that not everyone has benefited equally from this collective wealth. While the level of (market-based minimal food survival) poverty is relatively low in Canada (around 8.8%), poverty rates are much higher among particular groups, Aboriginal peoples being notable among them. According to the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, fifty percent of First Nations children in Canada live in poverty, a figure that increases to two thirds in regions of the provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba.[8] The study also found that children on reserves were in the worst situation, often living with poor or no drinking water and in run-down homes.

Fragmented History Education

Canadian students learn history incrementally from one year to another. The educational assumption is that by the time they graduate, they will have acquired a full exposure to Canadian history. Unfortunately, curricula and official examinations are structured sequentially – meaning step by step from one “event-space” to another – as if we were to turn national history into a sausage sliced into small, digestible bits and pieces of brain food.

The result of this curricular fragmentation is consequential. Students graduate without large-scale narrative patterns in national history (such as wealth, life expectancy, literacy, citizenship rights, etc.), but with only fragmented stories of short historical episodes. Perhaps more problematically, they fail to see how the past can inform the present and shape their own lives. As one Grade 12 student once put it: “I don’t remember much of what we learned in history.”

What I propose is a different way of conceiving historical perspective and of how we judge change over time. We need to (re)imagine history as a living object that can be studied in ways that make it possible to zoom in on particular sets of data and phenomena without losing the synoptic view of the whole. Citizens can only evaluate the progress or decline of their society over time if they have key standards and multiple schematic frameworks at their disposal to plot their ideas within a large-scale context. These frameworks, as Shemilt reminds us, are only provisional scaffolds within which people can move about as they encounter new evidence in their mid- or high-resolution analysis of history. In the end, we need learners to understand that big-picture frameworks are cognitive tools for generalization and historical interpretation. Where the viewer stands in relation to history is also critical, both because of their positionality in the present and because of the historicity that is being brought to task.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Roser, Max. “The short history of global living conditions and why it matters that we know it.” Our World In Data. February 2018. https://ourworldindata.org/a-history-of-global-living-conditions-in-5-charts (last accessed 13 February 2018).

- Shemilt, Denis. “Drinking an Ocean and Pissing a Cupful.” In National History Standards: The Problem of the Canon and the Future of Teaching History, edited by Linda Symcox and Arie Wilschut, 141-210. Charlotte NC: Information Age Publishing, 2009.

Web Resources

- OECD special project. “How was life?” http://www.oecd.org/statistics/how-was-life-9789264214262-en.htm (last accessed 13 February 2018).

- Free Geography tools. http://freegeographytools.com/2007/colored-countrysubdivision-google-earth-polygons-with-color-your-map (last accessed 13 February 2018).

_____________________

[1] The author would like to thank Penney Clark (UBC) as well as the organizers of the Historical Thinking Summer Institute 2017 for constructive feedback on drafts of this article.

[2] Peter Seixas, “Culture, civilization and historical consciousness,” Public History Weekly 5 (2017): 41, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10620 (last accessed 13 February 2018). On the notion of progress, see also Stéphane Lévesque, Thinking Historically: Educating Students for the 21st century (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008), chap. 5.

[3] Jörn Rüsen, History: Narration, Interpretation, Orientation (New York: Berghahn Books, 2005).

[4] Denis Shemilt, “Drinking an Ocean and Pissing a Cupful,” in National History Standards: The Problem of the Canon and the Future of Teaching History, eds. Linda Symcox and Arie Wilschut (Charlotte NC: Information Age Publishing, 2009), 141-210.

[5] For a detailed, applied discussion on this big-picture analogy in history education, see Rick Rogers, “Frameworks for Big History: Teaching History at Its Lower Resolution,” in MasterClass in History Education, eds. Christine Counsell, Katharine Burn and Arthur Chapman (London: Bloomsbury, 2016).

[6] For a thorough review of living conditions and economy over time, see Max Roser, “The short history of global living conditions and why it matters that we know it,” Our World In Data, https://ourworldindata.org/a-history-of-global-living-conditions-in-5-charts (last accessed 8 February 2018).

[7] William Watson, “Look at how Canadians lived 150 years ago and be very, very grateful,” Financial Post, June 29, 2017, http://business.financialpost.com/opinion/william-watson-look-at-how-canadians-lived-150-years-ago-and-be-very-very-grateful (last accessed 8 February 2018). For a detailed historical overview of life, well-being, and economy since the nineteenth century in various countries, see the OECD special project “How was life?”, http://www.oecd.org/statistics/how-was-life-9789264214262-en.htm (last accessed 7 February 2018).

[8] David Macdonald and Daniel Wilson, “Poverty or Prosperity: Indigenous children in Canada,” Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, June 19, 2013, https://www.policyalternatives.ca/publications/reports/poverty-or-prosperity (last accessed 7 February 2018).

_____________________

Image Credits

Image NASA © TerraMetrics Google

Recommended Citation

Lévesque, Stéphane: Are Things Getting Better or Worse? Seeing the “Big Picture” in Canadian History. In: Public History Weekly 6 (2018) 8, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-11329.

Das 150. Jubiläum der Kanadischen Konföderation im Jahr 2017 bietet eine einmalige Gelegenheit, um die Geschichte des Landes zu reflektieren und die gesellschaftliche Entwicklung in Kanada zu analysieren.[1] Glauben die KanadierInnen, dass sich während der vergangenen 150 Jahre die Dinge gebessert haben? Darüber herrscht Uneinigkeit. Ein Ursache dafür ist in der Beurteilung des Begriffs ‘Fortschritt’ und damit verbundener Veränderungen zu suchen. So wie auch die von Peter Seixas diskutierte Auffassung zur Zivilisation bleibt das Konzept “Fortschritt” umstritten.[2]

Die Notwendigkeit einer historischen Perspektive

Um die einleitende Frage zu beantworten, ist es nötig, eine historische Perspektive einzunehmen.Wir können kein kritisches Urteil über den historischen Wandel abgeben, ohne vorher die Ereignisse in einen zeitlichen Kontext zu stellen und somit unsere Analyse in einem längeren zeitlichen Verlauf zu verankern. Die Historische Perspektive ist, zumindest in meiner Absicht, gleichzusetzen mit dem big picture (“Gesamtbild”) der Geschichte. Normalerweise sind DidaktikerInnen an der historischen Perspektive interessiert, um damit über ein Analysewerkzeug zu verfügen, das es erlaubt, die Unterschiede zwischen Vergangenheit und Gegenwart, d.h. zwischen vergangenen und gegenwärtigen Lebensstilen zu unterscheiden. Es gibt jedoch auch ein anderes Verständnis, das die Fähigkeit umfasst, Erfahrungen und Veränderungen in einem zeitlichen Ganzen zu konstruieren, das die Vergangenheit mit der Gegenwart und unsere Zukunft mit dem Konzept der Kontinuität verbindet. Durch die historische Perspektive schaffen wir durch Interpretation der Vergangenheit Narrationen, die sich um unseren Alltag drehen.

Denis Shemilt zufolge können verschiedene “big picture“-Konzepte rund um die Bereiche menschlicher Aktivitäten entwickelt werden, die durch das längerfristige Betrachten vergangener menschlicher Belange eine synoptische Perspektive der Gegenwart bieten.[4] Um eine Google-Analogie zu verwenden: Big pictures ermöglichen uns, die Geschichte so wahrzunehmen, wie wir unseren Planeten via Google Earth betrachten können. Einerseits können wir hineinzoomen, um Schlüsselorte möglichst detailliert zu betrachten, andererseits können wir aber auch hinauszoomen, um ganze Kontinente und sogar die gesamte Welt zu sehen.[5] Von dieser großen Distanz aus ist es für das bloße Auge unmöglich, geographische Merkmale wie Flüsse oder Städte zu erkennen. Mit Sicherheit erkennen wir aber den größeren Zusammenhang mit seinen globalen Phänomenen wie den Wolkenformationen, der Umweltverschmutzung und der globalen Erwärmung. Das historische Pendant der Flüsse und Städte sind historische Figuren und große Ereignisse, während die Kontinente, Wolken und Ozeane gesellschaftliche Aspekte (wie Produktionsweisen, politische Organisationen, Kultur etc.) entsprechend der longue durée der Geschichte darstellen, wie sie Fernand Braudel einst bezeichnete.

Big pictures der kanadischen Geschichte

Betrachten wir also die kanadische Geschichte als ein big picture, um zu begreifen, wie all das aussehen mag! Natürlich mögen zehn, zwanzig oder sogar fünfundzwanzig Jahre für eine größere Perspektive der geschichtlichen Entwicklung Kanadas nicht reichen. Wir müssen eine langfristigere Perspektive berücksichtigen, damit wir Veränderungen über die Zeit hinweg verstehen können.[6]

Ein solches analytisches Gefüge ist der kollektive Wohlstand. Als G7-Mitglied ist Kanada ein relativ reiches Land mit einer ökonomischen Struktur, die von einer ländlichen Agrarwirtschaft bis zu einer modernen, höchst urbanisierten, dienstleistungsorientierten Wirtschaft reicht. Zu Beginn der Konföderation hatte Kanada ein BIP pro Kopf von $ 1.451 (in konstanten US$ im Jahr 1990).[7] Die Regierung verfügte über ein Budget von $ 14 Millionen (CAD$) – eine Staatsausgaben-BIP-Quote von circa 5 %. In den 2010er Jahren erreichte das BIP pro Kopf $ 24.941 (US$ im Jahr 1990). Hinsichtlich des Budgets wird erwartet, dass die gesamten Staatsausgaben bis Ende 2017 $ 331 Milliarden (CDN$) und die Staatsausgaben-BIP-Quote circa 15,6 % erreichen werden. Das bedeutet, dass Kanada viel reicher als vor 150 Jahren ist und wesentlich mehr in Programme und Dienstleistungen als im Jahre 1867 investiert. Obwohl diese Veränderungen vor langer Zeit starteten, nahmen sie nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg durch die rapide Industrialisierung Kanadas zu. Das fiel zeitlich auch mit einer stärkeren Beteiligung des Staates an der Wirtschaft zusammen. Ziel war, eine egalitärere Gesellschaft durch Umverteilung – den Sozialstaat – zu schaffen.

Wenn wir jedoch in bestimmte Regionen und Bevölkerungsgruppen hineinzoomen, wird deutlich, dass nicht alle gleich von diesem Wohlstand profitiert haben. Obwohl die (an der Beschaffung des Lebensmittelgrundbedarfs ausgerichtete) Armutsgrenze in Kanada relativ niedrig ist (circa 8,8%), ist der Armutsanteil in bestimmten Gruppen viel höher, erkennbar etwa bei der autochthonen Bevölkerung. Laut dem Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) leben 50 % der Kinder die den First Nations angehören, in Armut, in den Provinzen Saskatchewan und Manitoba sind es sogar zwei Drittel.[8] Die Studie zeigte, dass es Kindern, die in Reservaten leben, am schlechtesten geht, zumal sie oft verunreinigtes oder gar kein Trinkwasser haben und in heruntergekommenen Häusern wohnen.

Fragmentierter Geschichtsunterricht

Kanadische SchülerInnen lernen schrittweise Geschichte von einem Jahr zum anderen. Auf der fachdidaktischen Ebene wird angenommen, dass sie zur Zeit ihres Abschlusses ein umfassendes Wissen über die kanadische Geschichte erworben haben. Curricula und Prüfungen sind aufeinander aufgebaut – führen also Schritt für Schritt von einem Ereignis zum nächsten – als ob die Nationalgeschichte, wie ein Würstchen, in kleine, mundgerechte Stücke Gehirnnahrung zerteilt werden würde.

Das Ergebnis dieser curricularen Fragmentierung bleibt nicht ohne Folgen. SchülerInnen schließen ohne umfassende Kenntnisse der Nationalgeschichte (bzgl. Wohlstand, Lebenserwartung, Alphabetisierung, BürgerInnenrechte etc.) ab, stattdessen lediglich mit bruchstückhaftem Wissen über kurze historische Episoden. Scheinbar problematischer ist es, dass sie nicht fähig sind, vergangene Ereignisse, aus denen sie lernen können und die ihre Zukunft bilden, zu erkennen. Wie ein Schüler der 12. Klasse einmal sagte: “Ich erinnere mich nicht wirklich daran, was wir in Geschichte lernten.”

Ich schlage einen anderen Weg vor, wie historische Perspektive konzipiert wird und wie wir Veränderungen über die Zeit hinweg beurteilen können. Wir müssen Geschichte als lebendiges Objekt (neu) definieren, das so studiert werden kann, dass man die Möglichkeit hat, in bestimmte Dateneinheiten und Phänomene hineinzuzoomen, ohne den synoptischen Blick auf das Ganze zu verlieren. BürgerInnen können nur dann den Fortschritt oder den Rückschritt ihrer Gesellschaft über die Zeit hinweg evaluieren, wenn ihnen zentrale Standards und schematische Gefüge zur Verfügung stehen, die ihnen helfen, ihre Ideen im Rahmen eines Gesamtkontexts aufzufassen. Diese Gefüge sind laut Shemilt nur provisorische Gerüste, in denen die Menschen sich bewegen, während sie in ihrer mittel- oder hochauflösenden Geschichtsanalyse auf neue Beweise stoßen. Letztlich müssen die Lernenden verstehen, dass die big pictures kognitive Werkzeuge für die Verallgemeinerung und historische Interpretation sind. Wo sich die BetrachterInnen im Verhältnis zur Geschichte befinden, ist aufgrund ihrer Positionierung in der Gegenwart und ihrer Historizität, die sie mit sich bringen, von Bedeutung.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Roser, Max. “The short history of global living conditions and why it matters that we know it.” Our World In Data. February 2018. https://ourworldindata.org/a-history-of-global-living-conditions-in-5-charts (letzter Zugriff am 13.02.2018).

- Shemilt, Denis. “Drinking an Ocean and Pissing a Cupful.” In National History Standards. The Problem of the Canon and the Future of Teaching History, edited by Linda Symcox and Arie Wilschut, 141-210. Charlotte NC: Information Age Publishing, 2009.

Webressourcen

- OECD-Sonderprojekt “How was life?” http://www.oecd.org/statistics/how-was-life-9789264214262-en.htm (letzter Zugriff am 13.02.2018).

- Kostenlose Geographie-Tools. http://freegeographytools.com/2007/colored-countrysubdivision-google-earth-polygons-with-color-your-map (letzter Zugriff am 13.02.2018).

_____________________

[1] Der Autor möchte sich bei Penney Clark (UBC) und bei den VeranstalterInnen des Historical Thinking Summer Institute 2017 für die konstruktiven Rückmeldungen zum Konzept dieses Artikels bedanken.

[2] Peter Seixas, “Culture, civilization and historical consciousness,” Public History Weekly 5 (2017): 41, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10620 (letzter Zugriff am 13.02.2018). Zum Konzept des Fortschritts, siehe: Stéphane Lévesque, Thinking Historically. Educating Students for the 21st century (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008), Kap. 5.

[3] Jörn Rüsen, History. Narration, Interpretation, Orientation (New York: Berghahn Books, 2005).

[4] Denis Shemilt, “Drinking an Ocean and Pissing a Cupful,” in National History Standards. The Problem of the Canon and the Future of Teaching History, Hrsg. Linda Symcox und Arie Wilschut (Charlotte NC: Information Age Publishing, 2009), 141-210.

[5] Für eine detaillierte und angewandte Diskussion über diese “big picture“-Analogie im Geschichtsunterricht, siehe: Rick Rogers, “Frameworks for Big History. Teaching History at Its Lower Resolution,” in MasterClass in History Education, Hrsg. Christine Counsell, Katharine Burn und Arthur Chapman (London: Bloomsbury, 2016).

[6] Für einen ausführlichen Bericht zu den Lebensverhältnissen und der Wirtschaft im Laufe der Zeit, siehe: Max Roser, “The short history of global living conditions and why it matters that we know it,” Our World In Data, https://ourworldindata.org/a-history-of-global-living-conditions-in-5-charts (letzter Zugriff am 08.02.2018).

[7] William Watson, “Look at how Canadians lived 150 years ago and be very, very grateful,” Financial Post, 29. Juni 2017, http://business.financialpost.com/opinion/william-watson-look-at-how-canadians-lived-150-years-ago-and-be-very-very-grateful (letzter Zugriff am 08.02.2018). Für einen detaillierten historischen Überblick zum Leben, zum Wohlstand und zur Wirtschaft in verschiedenen Ländern seit dem 19. Jahrhundert, siehe das OECD-Sonderprojekt “How was life?” http://www.oecd.org/statistics/how-was-life-9789264214262-en.htm (letzter Zugriff am 07.02.2018).

[8] David Macdonald und Daniel Wilson, “Poverty or Prosperity. Indigenous children in Canada,” Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, 19. Juni 2013, https://www.policyalternatives.ca/publications/reports/poverty-or-prosperity (letzter Zugriff am 07.02.2018).

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

Bild NASA © TerraMetrics Google

Übersetzung

Stefanie Svacina and Paul Jones (paul.stefanie (at) outlook (dot) at)

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Lévesque, Stéphane: Wird alles besser oder schlechter? Ein Blick auf das “Gesamtbild” der kanadischen Geschichte. In: Public History Weekly 6 (2018) 8, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-11329.

Copyright (c) 2018 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 6 (2018) 8

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-11329

Tags: Canada (Kanada), Curriculum (Lehrplan), History Teaching (Geschichtsunterricht), Language: French