Abstract:

School history content curricula variously give learners an introduction to historical themes and outlines of their chronology, focus on key “turning point” events and may, additionally, provide in-depth topic studies. They don’t, however, convey well the complexity of the past. A recent reading of Jeff Guy’s seminal biography of John Colenso (1814 – 1873), first Church of England Bishop of Natal in South Africa, The Heretic, caused me to wonder what the school curriculum made of this history.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-9662.

Languages: English, Deutsch

School history content curricula variously give learners an introduction to historical themes and outlines of their chronology, focus on key “turning point” events and may, additionally, provide in-depth topic studies. They don’t, however, convey well the complexity of the past. A recent reading of Jeff Guy’s seminal biography of John Colenso (1814 – 1873), first Church of England Bishop of Natal in South Africa, The Heretic, caused me to wonder what the school curriculum made of this history.

Anglo-Zulu History in the Curriculum…

The current South African national curriculum, the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS)(2011),[1] includes the following in one of the six themes for Grade 10 (age 15):

“Colonial expansion after 1750

How did colonial expansion into the interior transform South Africa? The focus is on the impact that the demands of the emerging capitalist economy in Britain had on societies in southern Africa […]. A link can be made with the French Revolutionary wars, with Britain having taken control of the Cape in 1795, as well as the consolidation of British control and the impact this had after 1806. A broad understanding rather than detail is needed. […]

The Zulu kingdom and the colony of Natal

– the need for a controlled labour force: indentured Indian labourers (sugar); also labourers for railways and coal; and

– the Anglo-Zulu wars.”

…and Textbooks

I next went to a Grade 10 textbook, In Search of History [2] to find how it had interpreted the above specification. It includes three pages on the Anglo-Zulu wars (561 words). The following section concerns the war of 1879:

“The British were looking for an excuse to invade the Zulu kingdom. In 1879, the British in Natal deliberately stirred up a conflict with Cetshwayo [Zulu king]. They accused Cetshwayo of planning war and demanded that a British official be placed in the Zulu kingdom and that the Zulu army be disbanded. They knew that Cetshwayo would refuse to do this, and this would give Britain a reason to go to war. When Cetshwayo refused, the British army invaded Zululand in three separate groups. They all marched towards Cetshwayo’s capital at oNdini (Ulundi).

At first things went well for the Zulu army. They surrounded and defeated one group of British troops at Isandlwana, and killed almost all of them. This was one of Britain’s biggest defeats in all the colonial wars, and the British were shocked at the news. Settlers in Natal started to panic as they thought that the Zulu army would overrun the colony. A fierce battle took place on the border at Rorke’s Drift. The British troops were almost defeated before the Zulu withdrew.

The Zulu victory at Isandlwana allowed them to keep their independence for a little longer. However, Britain sent more troops to Zululand. Cetshwayo tried to reach an agreement with the British and sent peace messengers to meet with the generals in charge of the army. But the British ignored these attempts and then marched to Ulundi and destroyed the Zulu capital. Cetshwayo was captured and sent into exile in Cape Town.”

In this account, the British/British officials/settlers were uniformly opposed to the Zulu. The history was, however, far more complex than that. Guy (and other biographers) shows that Bishop Colenso, while a convinced supporter of Britain and Her Majesty’s government, was a friend and advisor to Cetshwayo, who assisted the “peace messengers” and went to extraordinary lengths to stand by him and the Zulu people. This included that after Isandlwana he urged Britain to delay the prosecution of the war until all possibility of negotiation had been explored; he undertook a remarkable, very detailed, correspondence with Colonial Office in London to correct the accounts of the Natal governors and officials and published pamphlets to place before the English public the facts of British rule in south-east Africa; and after the war he negotiated the release of Cetshwayo in Cape Town and was mainly responsible for Cetshwayo’s invitation to put his case in London in 1882, where he was received by Queen Victoria and, in Guy’s words, was “mobbed in the streets” by admirers.[3]

Colenso and the Complexity of the Past…

The present curriculum is specified in more detail than the previous National Curriculum Statement (2003),[4] which did not include any reference to the Anglo-Zulu war of 1879. Given the central place of the war in the history of the colonisation of South Africa, there is no doubt that it should be specified for study. But the above example shows that merely specifying the event does not ensure that it is dealt with in a way that reveals its complexity. Though there are obvious limits to the extent of specification,[5] the dangers of simplification or omission are real.[6]

The metanarrative of the textbook account is that all the British were opposed to the Zulu, waged war on them and seized their land. The account of Colenso (and the small number of colonists who supported him) introduces a different morality to the narrative. Colenso fought for justice for the Zulu and King Cetshwayo[7] — and paid a very high price for it in his subsequent “disappointment and pain”, leading to his death.[8] Guy summarises that Colenso was able to identify and publicise the manner in which falsification, the exploitation of fear and insecurity and the manipulation of public information a century and a half ago fomented the violence which prepared the way for the foundation of modern South Africa.[9] This, surely, is helpful to classroom history discussion today.

…and Curriculum Content Specification

Colenso’s role highlights issues of decolonising the curriculum. The complexity revealed equates to what Jansen has recently described as “encounters with entangled knowledge” that is, knowledge “not neatly separated into the neat binaries of “them” and “us”, “coloniser” and “colonised” and “the South”, “the West” and “the rest of us”. Instead our knowledges, like our human existences, are intertwined in the course of daily living, learning, and loving”.[10]

At one remove Colenso is a dedicated servant of Britain,[11] who sees benefit in the extension of British rule in Natal, but at another he stands resolutely against the administration and government of the colony and committed to the Zulu nation. Decolonisation requires not only viewing the past from the Zulu perspective, but understanding the complexity of the human relations involved.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Guy, Jeff . The Heretic. A study of the life of John William Colenso 1814-1883. Johannesburg: Raven Press, 1983.

- Hinchliff, Peter. Colenso, John William (1814–1883), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: University Press, 2004, online edition, May 2006, last accessed 11 May 2017).

- Jansen, Jonathan. As by fire. The end of the South African University. Cape Town: Tafelberg, 2017.

Web Resources

- What’s in the CAPS package? A comparative study of the National Curriculum Statement (NCS) and the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement. Further Education and Training Phase: Social Sciences. www.umalusi.org.za/social_sciences.pdf (last accessed 8 June 2017).

- Muhammad Nakhooda, Decolonised curriculum: A matter of mindfulness, www.dailymaverick.co.za/decolonised-curriculum-a-matter-of-mindfulness (last accessed 8 June 2017).

_____________________

[1] Department of Basic (2011) Education Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) Further Education and Training Phase Grades 10-12. History, p.17 (www.education.gov.za/National Curriculum Statements and Vocational, last accessed 8 June 2017).

[2] Jean Bottaro and Pippa Visser, In Search of History Grade 10. (Cape Town: Oxford University Press, 2011), 148.

[3] Jeff Guy, The Heretic. A study of the life of John William Colenso 1814-1883, (Johannesburg: Raven Press, 1983), 258, 273, 274, 284, 322, 291, 307, 326. Peter Hinchliff, Colenso, John William (1814–1883).

[4] Umalusi, the South African quality assurance authority for the school curriculum, conducted an evaluation of the CAPS (2011) curriculum. One aspect involved the degree of specification of topics, where it was found with a related topic that “the CAPS specifies clearly what the teacher needs to teach and assess”, in contrast to the 2003 curriculum. What’s in the CAPS package? A comparative study of the National Curriculum Statement (NCS) and the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement. Further Education and Training Phase: Social Sciences, p.82. www.umalusi.org.za/social_sciences.pdf, last accessed 8 June 2017.

[5] See, for example, the discussion on omission in school history textbooks: John Wilkes, “Making the best use of text books”. Teaching History no 18 (1977), 18-20.

[6] Interestingly, the CAPS (2011) curriculum experimented with including a detailed historiographical note (see Transformations in southern Africa after 1750, p.16) for the information/direction of textbook writers in order to elucidate the complexity intended in a topic, raising the question that if one were to make it a practice, how often should it be done?

[7] Jeff Guy, The Heretic. A study of the life of John William Colenso 1814-1883, (Johannesburg: Raven Press, 1983), 291.

[8] Jeff Guy, The Heretic. A study of the life of John William Colenso 1814-1883, (Johannesburg: Raven Press, 1983), 359.

[9] Jeff Guy, The Heretic. A study of the life of John William Colenso 1814-1883, (Johannesburg: Raven Press, 1983), 358-359.

[10] Jonathan Jansen, As by fire. The end of the South African University, (Cape Town: Tafelberg, 2017), 162.

[11] Jeff Guy, The Heretic. A study of the life of John William Colenso 1814-1883, (Johannesburg: Raven Press, 1983), 287.

_____________________

Image Credits

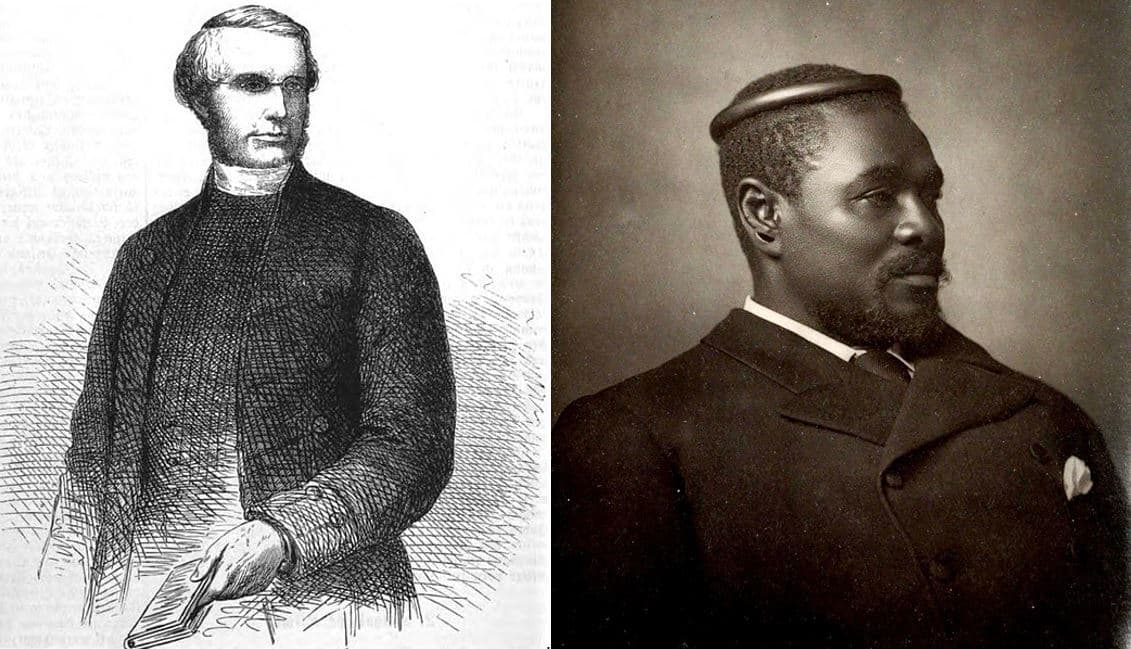

Compilation of Cetshwayo ka Mpande and John William Colenso © Compilation by Robert Siebörger; Picture of Cetshwayo ka Mpande taken by Alexander Bassano (1829-1913) and published in Frances Ellen Colenso. The Ruin of Zululand. An Account of British Doings in Zululand since the Invasion of 1879 in two Volumes. Volume II. London: William Ridgway, 1885. Source: www.wikimedia.org/Cetshwayo_kaMpande (last accessed 5 July 2017); Picture of John William Colenso published in Illustrierter Kalender, 20 (1865), 21. Artist: Unknown. Source: www.wikimedia.org/John_William_Colenso (last accessed 5 July 2017).

Recommended Citation

Siebörger, Robert: Complexity in the specification of the history curriculum. In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 27, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-9662.

In vielfacher Weise geben Lehrpläne für den Geschichtsunterricht eine Einführung zu historischen Themen und einen chronologischen Überblick für die Lernenden vor, rücken Schlüsselgeschehnisse mit “Wendepunktcharakter” in den Mittelpunkt und verlangen manchmal zusätzlich tiefgründige thematische Einblicke. Jedoch akzentuieren sie die Komplexität von Vergangenem nicht besonders gut. Die Lektüre von Jeff Guys bahnbrechender Biographie über John Colenso (1814 – 1873), den ersten Bischof der Church of England von Natal in Südafrika, The Heretic, liess in mir die Frage aufkommen, was denn der Schullehrplan aus dieser Geschichte macht.

Die Geschichte der Anglo-Zulu im Lehrplan …

Der aktuelle staatliche Lehrplan “The Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS)(2011)”,[1] macht in einem der sechs Themenbereiche für die 10. Klasse (Alter 15) folgende Vorgaben:

“Koloniale Expansion nach 1750

Auf welche Weise hat die koloniale Expansion ins Innere Südafrika verändert? Der Schwerpunkt liegt auf den Auswirkungen, die die Ansprüche der aufstrebenden kapitalistischen Wirtschaft in Grossbritannien auf die Gesellschaften im südlichen Afrika hatten […]. Ein Zusammenhang kann hergestellt werden mit den französischen Revolutionskriegen, mit Großbritannien, welches das Kap im Jahre 1795 unter seine Kontrolle gebracht hatte, ebenso wie mit der Konsolidierung der britischen Herrschaft und den Folgen, die dies nach 1806 hatte. Es ist mehr ein breites Verständnis gefordert als Details. […]

Das Zulu Königreich und die Kolonie von Natal

– der Bedarf an beaufsichtigten Arbeitskräften: an vertraglich verpflichteten indischen Arbeitern (Zuckeranbau); ebenso an Arbeitern für die Eisenbahnen und den Kohlenabbau; und

– die Anglo-Zulu Kriege.”

… und in Lehrmitteln

Ich wandte mich sodann dem Lehrmittel für die 10. Klasse In Search of History[2] zu, um zu erkunden, wie obige Vorgaben umgesetzt worden sind. Die Umsetzung im Schulgeschichtsbuch bietet drei Seiten über die Anglo-Zulu Kriege (561 Worte). Der folgende Abschnitt betrifft den Krieg von 1879:

“Die Briten suchten nach einer Entschuldigung, um in das Zulu-Reich einmarschieren zu können. Im Jahre 1879 zettelten die Briten einen Streit mit Cetshwayo [dem Zulu-König] an. Sie beschuldigten Cetshwayo, einen Krieg zu planen, und verlangten, dass ein britischer Beamte im Zulu-Reich eingesetzt und dass die Zulu-Armee aufgelöst werde. Sie wussten genau, dass sich Cetshwayo weigern würde, diesem Ansinnen nachzukommen, was den Briten den Anlass geben würde, einen Krieg vom Zaun zu brechen. Als sich Cetshwayo dem entgegensetzte, drang die britische Armee in drei separaten Abteilungen in das Zulu-Land ein. Alle drei marschierten in Richtung auf Cetshwayos Hauptstadt in oNdini (Ulundi) zu.

Zuerst verliefen die Dinge gut für die Zulu-Armee. Sie umzingelten und besiegten eine Abteilung der britischen Truppen in Isandlwana und brachten fast alle Angehörigen um. Dies war eine der grössten Niederlagen der Briten in all den Kolonialkriegen, und die Briten waren von den Nachrichten geschockt. Die Siedler in Natal gerieten beim Gedanken, dass die Zulu-Armee die Kolonie überrennen würde, in Panik. Ein heftiger Kampf ereignete sich an der Grenze zu Rorke’s Drift. Die britischen Truppen standen knapp vor der Niederlage, als die Zulus sich zurückzogen.

Der Zulu-Sieg in Isandlwana ermöglichte es ihnen, ihre Unabhängigkeit ein wenig länger zu wahren. Die Briten sandten dann jedoch zusätzliche Truppen ins Zulu-Gebiet. Cetshwayo machte den Versuch, mit den Briten ein Abkommen auszuhandeln und sandte Friedensbotschafter aus, um die die Armee kommandierenden Generäle zu treffen. Die Briten ignorierten diese Bestrebungen jedoch und marschierten daraufhin auf Ulundi zu und zerstörten die Hauptstadt der Zulu. Cetshwayo wurde gefangen genommen und ins Exil nach Kapstadt geschickt.”

In dieser Darstellung stehen die Briten/die britischen Beamten/die Siedler den Zulu feindlich gegenüber. Die Geschichte war jedoch weit komplexer als diese vereinfachte Darstellung suggeriert. Guy (und weitere Biographen) zeigen auf, dass Bischof Colenso – obwohl er ein überzeugter Anhänger von Großbritannien und der Regierung Ihrer Majestät – auch ein Freund und Berater von Cetshwayo war, der den “Friedensbotschaftern” beistand und außergewöhnliche Anstrengungen unternahm, um ihm und dem Volk der Zulu zur Seite zu stehen. Dies schloss mit ein, dass er nach der Schlacht bei Isandlwana Großbritannien dazu drängte, die Fortführung des Krieges zu verzögern, bis alle Verhandlungsmöglichkeiten ausgeschöpft worden waren. Er führte eine beachtenswerte, detaillierte Korrespondenz mit dem Kolonialamt in London, um die Darstellungen der Gouverneure und Beamten von Natal zu berichtigen, und veröffentlichte Flugschriften, um die englische Öffentlichkeit über die wahren Hintergründe der britischen Herrschaft in Südostafrika aufzuklären. Und nach dem Krieg handelte er die Freilassung von Cetshwayo in Kapstadt aus und war hauptverantwortlich für die Einladung an Cetshwayo, seinen Fall in London 1882 in London darzulegen, wo er von Queen Victoria empfangen wurde und, in Guys Worten, von den Verehrern “auf den Strassen bestürmt wurde”.[3]

Colenso und die Komplexität der Vergangenheit …

Der vorliegende Lehrplan umfasst ein grösseres Ausmass an detaillierten Vorgaben als die vorhergehende staatliche Lehrplanversion (2003),[4] die keinen Bezug zum Anglo-Zulu-Krieg von 1879 beinhaltete. Angesichts der zentralen Stellung des Krieges in der Kolonisationsgeschichte von Südafrika besteht kein Zweifel, dass seine Behandlung eine Vorgabe sein müsste. Obiges Beispiel zeigt jedoch auf, dass das bloße Vorgeben des Geschehnisses nicht sicherstellt, dass es auf eine Weise behandelt wird, die seiner Komplexität gerecht wird. Obwohl dem Ausmaß von Vorgaben offensichtliche Grenzen gesetzt sind,[5] stellt die Gefahr einer Simplifizierung oder Auslassung eine absolute Realität dar.[6]

Das Meta-Narrativ der Darstellung im Lehrmittel suggeriert, dass alle Briten den Zulus feindlich gegenüberstanden, Krieg gegen dieselben führten and ihr Land an sich rissen. Die Darstellung von Bischof Colenso (und die kleine Zahl von Kolonisten, die ihn unterstützte) bringt eine andere Moralität in das Narrativ ein. Colenso kämpfte für die Gerechtigkeit gegenüber den Zulus und König Cetshwayo [7] — und zahlte dafür einen sehr hohen Preis infolge der nachträglichen “Enttäuschung und des Schmerzes”, die ihm den Tod brachten.[8] Guy stellt zusammenfassend dar, dass Colenso in der Lage war, die Art und Weise auf den Punkt zu bringen und öffentlich zu machen, und wie Verfälschungen, das sich Zu-nutze-Machen von Angst und Unsicherheit ebenso wie die Manipulation öffentlicher Information vor anderthalb Jahrhunderten die Gewalt schürten, die den Weg ebnete für die Gründung des modernen Südafrikas.[9] Dies wäre sicher nützlich für den Geschichtsunterricht heutzutage.

… und die inhaltlichen Lehrplanvorgaben

Colensos Rolle hebt die Thematik der Dekolonisierung von Lehrplänen hervor. Die aufgedeckte Komplexität kommt dem gleich, was Jansen vor nicht allzu langer Zeit als “Begegnungen mit dem verstrickten Wissen” beschrieben hat, das heisst, Wissen, welches “nicht genau trennt zwischen der klaren Binarität von “ihnen” und “uns”, “Kolonisator” und “Kolonisierter” und “der Süden” und “der Westen” und “der Rest von uns”. Stattdessen verwickelt sich unser Wissen, wie unsere menschlichen Existenzen, im Laufe des täglichen Lebens, Lernens und Liebens.”[10]

Auf der einen Seite ist Colenso ein ergebener Diener Grossbritanniens,[11] der den Nutzen in der Ausweitung der britischen Herrschaft in Natal erkennt, auf der anderen Seite aber stellt er sich resolut der Administration und Regierung der Kolonie entgegen und fühlt sich dem Volke der Zulu verpflichtet. Dekolonisierung erfordert nicht nur, dass die Vergangenheit von der Perspektive der Zulu aus betrachtet wird, sondern dass auch das Verständnis für die Komplexität der darin involvierten menschlichen Beziehungen nicht fehlt.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Guy, Jeff . The Heretic. A study of the life of John William Colenso 1814-1883. Johannesburg: Raven Press, 1983.

- Hinchliff, Peter. Colenso, John William (1814–1883), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: University Press, 2004, online edition, May 2006, last accessed 11 May 2017).

- Jansen, Jonathan. As by fire. The end of the South African University. Cape Town: Tafelberg, 2017.

Webressourcen

- What’s in the CAPS package? A comparative study of the National Curriculum Statement (NCS) and the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement. Further Education and Training Phase: Social Sciences. www.umalusi.org.za/social_sciences.pdf (letzter Zugriff am 08.06.2017).

- Muhammad Nakhooda, Decolonised curriculum: A matter of mindfulness, www.dailymaverick.co.za/decolonised-curriculum-a-matter-of-mindfulness (letzter Zugriff am 08.06.2017).

_____________________

[1] Department of Basic (2011) Education Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) Further Education and Training Phase Grades 10-12. History, S.17 (www.education.gov.za/National Curriculum Statements and Vocational, letzter Zugriff am 08.06.2017).

[2] Jean Bottaro/Pippa Visier (Hrsg.): In Search of History Grade 10. Kapstadt 2011. S. 148.

[3] Jeff Guy: The Heretic. A study of the life of John William Colenso 1814-1883. Johannesburg 1983. S.258, 273, 274, 284, 322, 291, 307, 326. Peter Hinchliff: Colenso, John William (1814–1883), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. Online-Edition, Mai 2006, letzter Zugriff am 11.06.2017)..

[4] Umalusi, die südafrikanische Qualitätssicherungsstelle für Schullehrpläne führte eine Evaluation des CAPS (2011) Lehrplans durch. Einer der miteinbezogenen Aspekte war das Ausmass der Vorgaben bezüglich Themen; wobei beim diesbezüglichen Thema eruiert wurde, dass «der CAPS Lehrplan klar vorgibt, was der Lehrer zu unterrichten und bewerten hat», im Gegensatz zum Lehrplan von 2003. What’s in the CAPS package? A comparative study of the National Curriculum Statement (NCS) and the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement. Further Education and Training Phase: Social Sciences, S.82.

http://www.umalusi.org.za/docs/reports/2014/social_sciences.pdf.

[5] Siehe z.B. die Diskussion um die Gestaltung von Schulgeschichtsbüchern bei John Wilkes: Making the best use of text books. In: Teaching History 18 (1977), S. 18-20.

[6] Interessanterweise experimentierte der CAPS (2011) Lehrplan mit dem Einfügen einer detaillierten historiographischen Anmerkung (siehe Transformations in Southern Africa after 1750, S.16) zur Information/Anleitung von Lehrmittelautoren, um die im Thema angestrebte Komplexität zu verdeutlichen und warf dabei die Frage auf, wie oft dies getan werden müsse, falls man dies zur Praxis machen sollte.

[7] Jeff Guy: The Heretic. A study of the life of John William Colenso 1814-1883. Johannesburg 1983. S.291.

[8] Jeff Guy: The Heretic. A study of the life of John William Colenso 1814-1883. Johannesburg 1983. S.359.

[9] Jeff Guy: The Heretic. A study of the life of John William Colenso 1814-1883. Johannesburg 1983. S.358-359.

[10] Jonathan Jansen: As by fire. The end of the South African University. Kapstadt 2017. S.162.

[11] Jeff Guy: The Heretic. A study of the life of John William Colenso 1814-1883. Johannesburg 1983. S.287.

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

Bildmontage von Cetshwayo ka Mpande und John William Colenso © Bildmontage von Robert Siebörger; das Foto von Cetshwayo ka Mpande wurde von Alexander Bassano (1829-1913) aufgenommen und in Frances Ellen Colenso: The Ruin of Zululand. An Account of British Doings in Zululand since the Invasion of 1879 in two Volumes. Volume II. London, 1885. publiziert, Quelle: www.wikimedia.org/Cetshwayo_kaMpande (letzter Zugriff am 05.07.2017). Das Foto von John William Colenso wurde in Illustrierter Kalender, 20 (1865), S. 21 publiziert. Künstler: Unbekannt. Quelle: www.wikimedia.org/John_William_Colenso (letzter Zugriff am 05.07.2017).

Übersetzung

Kurt Brügger swissamericanlanguageexpert

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Siebörger, Robert: Die Komplexität von Geschichtslehrplan-Vorgaben. In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 27, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-9662.

Copyright (c) 2017 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 5 (2017) 27

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-9662

Tags: Africa, Colonial Legacy (Koloniales Erbe), Curriculum (Lehrplan), Postcolonial Perspectives, South Africa (Südafrika), Textbook (Schulbuch)