Abstract: “It’s embarrassing, it’s an ugly part of our history.”[1] says Daniel Elliot, Indigenous descendant of residential school survivors, “What I want to see from the Commission is to rewrite the history books so that other generations will understand and not go through the same thing that we’re going through now, like it never happened.”[2] The recent report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada called on educational institutions to decolonize our system: “The way we educate our children and ourselves must change. Thinking must change.”

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-7043.

Languages: Français, English, Deutsch

“C’est gênant, c’est une partie affreuse de notre histoire”, souligne Daniel Elliott, descendant des survivants des pensionnats autochtones.[1] On ne veut pas l’entendre. “Ce que je veux de la Commission, c’est qu’elle réécrive les livres d’histoire pour que les autres générations comprennent et ne vivent pas ce que nous vivons aujourd’hui, c’est-à-dire de faire comme si ce n’était jamais arrivé”. Le rapport de la Commission de vérité et réconciliation (CVR) du Canada est sans équivoque. Les commissaires ne demandent pas moins que de décoloniser le système scolaire actuel : La façon dont nous éduquons nos enfants et nous éduquons nous-mêmes doit changer. Les mentalités doivent changer.[2]

Comment intégrer les perspectives autochtones en éducation?

Comme d’autres nations issues du colonialisme la nécessité d’intégrer les perspectives autochtones dans l’histoire du pays se fait attendre. Mais comment s’y prendre? La décolonisation du système scolaire demeure encore obscure. Alors que beaucoup de professeurs et de maisons d’éditions sont disposés à intégrer des récits Autochtones à l’enseignement scolaire, il demeure encore beaucoup d’incertitude sur le but et la façon d’intégrer leurs perspectives.

En fait, le défi ne porte pas tant sur l’ajout de contenu plus inclusif; cela se fait déjà depuis plusieurs années notamment dans les manuels scolaires. Ce qui est véritablement en jeu dans le contexte actuel c’est la nature même de ce qu’est “l’histoire”. Les peuples autochtones remettent en question le modèle de production historique occidental jugé colonialiste et donc insensible à leurs perspectives.

Les demandes de décolonisation du système scolaire surviennent au moment même où l’éducation historique au pays s’oriente vers une pédagogie disciplinaire dite de la “pensée historique”. Comme le rapporte Peter Seixas, la pensée historique joue maintenant un rôle central dans les fondements et les pratiques éducatives au Canada.[3] A l’instar de la formation scientifique issue des sciences, l’éducation historique est passée d’une pédagogie du récit patriotique à une pédagogie de la pensée critique et le développement de compétences disciplinaires par situations-problèmes et analyse documentaires.

Enseigner selon les perspectives autochtones

Dans la mouvance de la Commission de vérité et réconciliation, la discipline historique a été fortement remise en question dû à son incapacité à bien (re)présenter les perspectives autochtones et leur façon particulière de mettre en relation le passé, le présent, et l’avenir de manière non-linéaire. Les penseurs autochtones soutiennent que l’historiographie occidentale, fondée sur l’analyse des sources historiques, l’agentivité et la rationalité humaine, le progrès et la modernité, est insensible aux mentalités autochtones, aux principes écologiques de leur modèle de pensée, et à leur façon cyclique de comprendre le temps.

Le professeur Michael Marker identifie quatre caractéristiques propres au modèle de pensée des Autochtones : (1) la nature circulaire du temps et des récits; (2) la relation symbiotique entre les humains, la nature et les animaux dans la construction du savoir et de la sagesse; (3) l’emphase sur le milieu local comme source absolue de compréhension du temps et de l’espace; et (4) les récits autochtones comme mode d’appréhension physique et métaphysique de l’expérience et qui remettent en question le colonialisme.[4]

Pour les peuples autochtones, la compréhension du passé ne peut donc s’exercer par un mode de pensée occidental basé sur un raisonnement qu’ils considèrent comme une logique coloniale. Cela ne peut se faire que par une “conscience historique indigène” qui s’appuie sur une conception organique du savoir et qui met en relation l’Homme, la nature et le milieu.

“Notre expérience coloniale”, soutient Linda Tuhiwai Smith, “nous enferme dans le projet de la modernité. Pour transformer nos conceptions colonialistes de notre histoire, il faut revoir, lieu par lieu, l’histoire occidentale”.[5]

Que peut-on faire?

Dans un article récent le chercheur David Newhouse pose la question : peut-on intégrer les modes de pensée autochtones au monde scientifique?[6] A cela nous pourrions ajouter : est-ce possible de réconcilier l’histoire canadienne avec la pensée écologique autochtone qui lie le monde animal et spirituel à celui des humains? L’histoire autochtone et l’histoire disciplinaire sont-elles compatibles? Ces questions fondamentales qui traversent les cultures et les nations n’ont pas de réponses simples et immédiates. Mais comme éducateurs il importe de se pencher sérieusement sur ces enjeux épistémologiques et éducatifs à la lumière des recommandations de la CVR.

Car on ne peut demander aux professeurs de “décoloniser” les savoirs scolaires et scientifiques ou d’adopter une conscience historique indigène sans avoir, au préalable, développé une compréhension aigüe du sujet. Si l’on souhaite que les citoyens, jeunes et adultes, aient une meilleure compréhension de l’histoire des pensionnats autochtones ou des modes de pensée des Autochtones, il ne suffit pas d’ajouter plus de récits à des programmes déjà surchargés.

La compétence narrative

Les récits, qu’ils proviennent d’historiens professionnels, de sages ou d’aînés, ne sont pas le passé et n’offrent en aucun cas pas une vision complète du passé. Il existe plusieurs types de récits en société qui peuvent à l’occasion se renfoncer ou se contredire. Pour être en mesure d’analyser et de faire appel aux récits historiques, il faut développer une compétence narrative.[7] Sans cette habileté à étudier la structure profonde des récits, ceux-ci peuvent aisément se confondre avec les mythes et les légendes. Un défi important dans la réalisation d’une éducation plus inclusive de l’histoire des Autochtones est d’amener les élèves à : (1) comprendre comment les récits autochtones et non-autochtones sont élaborés; (2) évaluer le pouvoir et l’importance de différents types de récits sur la vie personnelle, la culture et l’identité; et (3) produire leurs proposes récits du passé collectif qu’ils pourront mobiliser dans l’action.

On peut donc penser, comme le soutient Peter Seixas, que le contexte canadien est propice à une possible réconciliation entre les historiographies occidentales et autochtones.[8] La CVR offre d’ailleurs un exemple probant en faisant appel à l’expertise des historiens et aux récits oraux des Premières Nations de manière complémentaire, et ce pour dévoiler des vérités historiques largement inconnues.

Dans le monde actuel, les citoyens canadiens ont besoins des deux modes de pensée historique : disciplinaire et autochtone. On ne peut remplacer par opportunisme un mode de pensée par un autre au nom de la décolonisation. Si l’on souhaite former des citoyens critiques et pleinement engagés dans leur société les Canadiens doivent savoir quand et comment faire appel à ces différentes façons d’appréhender les réalités historiques et contemporaines.

_____________________

Littérature complémentaire

- Commission de vérité et réconciliation du Canada. Honorer la vérité, réconcilier pour l’avenir: Sommaire du rapport de la Commission de vérité et réconciliation du Canada, Ottawa: Imprimerie de la reine, 2015.

- Marker, Michael: “Teaching history from an Indigenous perspective.” Dans Clark, Penney (ed.) : New possibilities for the past: Shaping history education in Canada, Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 2011, p. 98–112.

- Seixas, Peter : “Indigenous historical consciousness: An oxymoron or a dialogue?” Dans Carretero, Mario / Ascensio, Mikel / Rodríguez-Moneo, Marìa (eds.) : History education and the construction of national identities, Charlotte, NC: Information Age, 2012, p. 125–138.

Liens externes

- Que sont les enfants devenus? Healing the legacy of residential schooling. The Legacy of Hope Foundation. http://lesenfantsdevenus.ca (consulté pour la dernière fois le 1 septembre 2016).

__________________

The author would like to thank Peter Seixas and Penney Clark for insightful comments on drafts of this version.

[1] Cet article est basé sur des réflexions provenant de conversations avec des collègues ainsi que de judicieuses recommandations de Penney Clark, Richard Maclure, Nicholas Ng-A-Fook et Peter Seixas.

[2] Commission de vérité et réconciliation du Canada. Honorer la vérité, réconcilier pour l’avenir: Sommaire du rapport de la Commission de vérité et réconciliation du Canada, Ottawa: Queen’s Printer for Canada, 2015.

[3] Seixas, Peter: “A Model of Historical Thinking, Educational Philosophy and Theory,” Educational Philosophy and Theory (2015). DOI: 10.1080/00131857.2015.1101363. Pour plus de détails sur les concepts de la pensée historique, voir http://historicalthinking.ca (consulté pour la dernière fois le 1 septembre 2016).

[4] Marker, Michael : “Teaching history from an Indigenous perspective.” Dans Clark, Penney (ed.), New possibilities for the past: Shaping history education in Canada, Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 2011, p. 98–112.

[5] Linda Tuhiwai Smith, cité dans Marker, “Teaching history from an Indigenous perspective,” 110.

[6] Newhouse, David : “The meaning of Indigenizing in our universities,” CAUT Bulletin 63, 6 (2016), A2.

[7] Voir mon article, Lévesque, Stéphane : “Going beyond “Narratives” vs. “Competencies”: A model for understanding history education,” Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 12, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-5918; et aussi Körber, Andreas / Meyer-Hamme, Johannes : “Historical thinking, competencies, and their measurement”, In: Ercikan, Kadriye / Seixas, Peter (eds.): New directions in assessing historical thinking, New York: Routledge, 2015, p. 89-101.

[8] Seixas, Peter : “Indigenous historical consciousness: An oxymoron or a dialogue?” Dans Carretero, Mario / Ascensio, Mikel / Rodríguez-Moneo, Marìa (eds.): History education and the construction of national identities, Charlotte, NC: Information Age, 2012, p. 125–138. Voir aussi Saul, John R. : The comeback, Toronto, ON: Viking, 2014); McGregor, Heather : “Exploring ethnohistory and Indigenous scholarship: What is the relevance to educational historians?” History of Education, 43(4), 431–449. DOI:10.1080/0046760X.2014.930184; et Anderson, Stephanie: “The Stories Nations Tell: Sites of Pedagogy, Historical Consciousness and History Education,” Canadian Journal of Education (à venir). Disponible bientôt: http://www.cje-rce.ca/index.php/cje-rce.

__________________

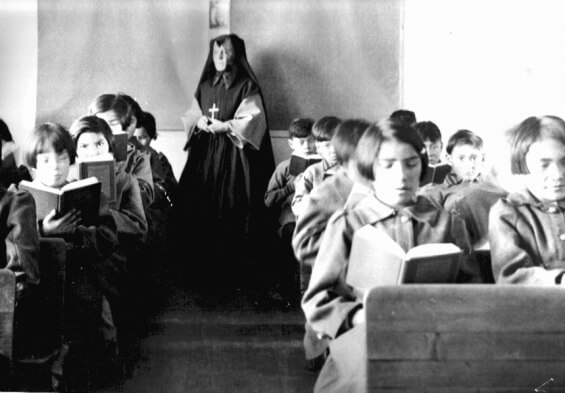

Crédits Illustration

Photograph of students from Fort Albany Residential School reading in class overseen by a nun c 1945. From the Edmund Metatawabin collection at the University of Algoma, Wikimedia Commons (consulté pour la dernière fois le 14 Septembre 2016).

Citation recommandée

Levesque, Stéphane: Histoire à l’ère de “la vérité et la réconciliation”. In: Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 29, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-7043

“It’s embarrassing, it’s an ugly part of our history.”[1] says Daniel Elliot, Indigenous descendant of residential school survivors, “What I want to see from the Commission is to rewrite the history books so that other generations will understand and not go through the same thing that we’re going through now, like it never happened.”[2] The recent report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada called on educational institutions to decolonize our system: “The way we educate our children and ourselves must change. Thinking must change.”[3]

How Should We Indigenize History Education?

As in other post-colonial nations, the need to integrate Indigenous perspectives in Canadian history is long overdue. But how should it be done? The “indigenization” of education is still a very unclear experiment. While most teachers – and publishers – are in the process of integrating more stories about Indigenous peoples, there is less consensus on how and why we should teach these.

The problem is not merely a matter of content inclusion: more stories on pre-contact with Europeans, more stories on residential schooling, and so on. The deeper challenge pertains to the very nature of “what counts as history.” Indeed, the current demands for Indigenous perspectives come precisely at a moment when history education is moving toward a more disciplinary, critical way of knowing the past.

Peter Seixas recently noted that historical thinking now has a central role in the theory and practice of education in Canada.[4] Like scientific thinking in the sciences, history education has gradually moved away from patriotic story-telling to critical thinking, inquiry-based learning, and the analysis of historical sources and multiple perspectives.

Teaching Indigenous Ways of Knowing

Disciplinary history has been criticized for its inability to represent Indigenous perspectives on the relationship between the past, present and envisioned future. Indigenous scholars claim that Western historiographies – with emphasis on historical evidence, human agency, progress, and modernity – disregard Indigenous understandings of the process of time and principles of ecological knowledge systems.

Aboriginal educator Michael Marker, for instance, has identified four characteristics of Indigenous ways of knowing: (1) the circular nature of time and ways of telling oral histories, with recurring events merged in a non-linear fashion; (2) the central relationship between humans, landscape, and animals as source of knowledge and wisdom; (3) the emphasis on local landscape as containing the full meaning of time and place; and (4) Indigenous narratives as both physical and metaphysical journeys that challenge histories of colonization.[5]

For Indigenous peoples, understanding the past cannot be accomplished through Western, evidence-based ways of thinking, which they see as “colonial logics”; it is only possible through an “Indigenous historical consciousness” that relies on organic knowledge that connects people, land, and nature.[6]

“Our colonial experience,” claims Linda Tuhiwai Smith, “traps us in the project of modernity […]. Transforming our colonized views of our own history […] requires us to revisit, site by site, our history under Western eyes.”[7]

What Can We Do?

In a recent article, Aboriginal scholar David Newhouse asks: Can we extend traditional Indigenous ways of knowing to scholarly endeavours?[8] To this we could add: Is it possible to integrate the sacred ecology of animals, spirits, and human agencies and cycles of life into the history of Canada? Are disciplinary and Indigenous ways of knowing irreconcilable? These fundamental questions, which cut across cultures and nations, have no easy answer. Yet, as Canadian educators, we need to think seriously about them as we progressively move toward implementing the recommendations of the TRC.

Indeed, telling teachers to decolonize received knowledge and teach through an Indigenous historical consciousness without proper understanding and training is a perfect recipe for catastrophe. If we want citizens – young and adult – to know more about the history of residential schooling and Indigenous ways of knowing, simply adding more stories to an already over-crowded curriculum will not do.

Narrative Competence

Stories – whether they are from trusted historians or elders – are not the past. Nor do they offer a full picture of the past. Many stories are told and they may contradict or complement one another. In order to make critical use of stories, narrative competence is necessary.[9] Without such an analysis of the deep structure of narratives, story-telling can easily lapse into myth-making. A central challenge in teaching the history of residential schooling is to help students (1) understand how different Indigenous and non-Indigenous narratives are constructed with various rhetorical devices; (2) assess the power and significance of these different forms of narrative for everyday life, culture, and identity; and (3) generate their own usable narratives of the collective past.

Seixas is thus right to claim that Western and Indigenous historiographies have a unique opportunity to come together in this period of reconciliation.[10] Traditional oral history and disciplinary history have been employed, sometimes collaboratively, to uncover historical truths about residential schooling experiences that might otherwise have remained unknown.

Canadians need both forms of history – the disciplinary and the Indigenous. We simply cannot replace one with the other in the name of “decolonization.” Perhaps more importantly, Canadians need to know how and when to make use of these different ways of knowing in order to promote reconciliation and to participate fully as citizens in the democratic life of this multicultural country.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Ottawa: Queen’s Printer for Canada, 2015.

- Marker, Michael. “Teaching history from an Indigenous perspective.” In New possibilities for the past: Shaping history education in Canada, edited by Penney Clark, 98-112. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 2011.

- Seixas, Peter. “Indigenous historical consciousness: An oxymoron or a dialogue?” In History education and the construction of national identities, edited by Mario Carretero, Mikel Ascensio and Marìa Rodríguez-Moneo, 125-138. Charlotte, NC: Information Age, 2012.

Web Resources

- Where are the children? Healing the legacy of residential schooling. The Legacy of Hope Foundation. http://wherearethechildren.ca (last accessed 21 July 2016).

_____________________

The author would like to thank Peter Seixas and Penney Clark for insightful comments on drafts of this version.

[1] My reflections are based on various conversations with colleagues and constructive feedback on drafts of this paper from Penney Clark, Richard Maclure, Nicholas Ng-A-Fook and Peter Seixas.

[2] Indigenous (or Aboriginal) peoples is a collective name for the original peoples of North America and their descendants. The Canadian constitution recognizes three groups of Indigenous peoples: First Nations (originally called “Indians”), Métis and Inuit. More than 1.4 million people in Canada identify themselves as an Aboriginal person, according to the 2011 National Household Survey.

[3] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Ottawa: Queen’s Printer for Canada, 2015. Available http://nctr.ca/reports.php (last accessed 21 July 2016).

[4] Seixas, Peter: “A Model of Historical Thinking, Educational Philosophy and Theory,” Educational Philosophy and Theory (2015). DOI: 10.1080/00131857.2015.1101363. For details on the key historical thinking concepts, see http://historicalthinking.ca (last accessed 21 July 2016).

[5] Marker, Michael: “Teaching history from an Indigenous perspective.” In Clark, Penney (ed.): New possibilities for the past: Shaping history education in Canada, Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 2011, p. 98–112.

[6] See Donald, Dwayne: “On making love to death: Plains Cree and Blackfoot wisdom,” Equity Matters (February 1, 2011). Available http://www.ideas-idees.ca/blog/making-love-death-plains-cree-and-blackfoot-wisdom; and also his “Forts, curriculum, and Indigenous métissage: Imagining decolonization of Aboriginal-Canadian relations in educational contexts.” First Nations Perspectives: The Journal of the Manitoba First Nations Education Resource Centre, 2, 1 (2007), p. 1–24.

[7] Linda Tuhiwai Smith, as quoted in Marker, “Teaching history from an Indigenous perspective,” p. 110.

[8] Newhouse, David: “The meaning of Indigenizing in our universities,” CAUT Bulletin 63, 6 (2016), A2.

[9] See my earlier post Lévesque, Stéphane: “Going beyond “Narratives” vs. “Competencies”: A model for understanding history education,” Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 12, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-5918; and also Körber, Andreas and Meyer-Hamme, Johannes: “Historical thinking, competencies, and their measurement”, In Ercikan, Kadriye / Seixas, Peter (eds.): New directions in assessing historical thinking, New York: Routledge, 2015, p. 89-101.

[10] Seixas, Peter: “Indigenous historical consciousness: An oxymoron or a dialogue?” In Carretero, Mario / Ascensio, Mikel / Rodríguez-Moneo, Marìa (eds.): History education and the construction of national identities, Charlotte, NC: Information Age, 2012, p. 125–138. See also Saul, John R.: The comeback, Toronto, ON: Viking, 2014; McGregor, Heather: “Exploring ethnohistory and Indigenous scholarship: What is the relevance to educational historians?” History of Education, 43(4), 431–449. DOI:10.1080/0046760X.2014.930184; and Anderson, Stephanie: “The Stories Nations Tell: Sites of Pedagogy, Historical Consciousness and History Education,” Canadian Journal of Education (forthcoming). Will be available: http://www.cje-rce.ca/index.php/cje-rce.

_____________________

Image Credits

Photograph of students from Fort Albany Residential School reading in class overseen by a nun c 1945. From the Edmund Metatawabin collection at the University of Algoma., Wikimedia Commons (last accessed 14 September 2016).

Recommended Citation

Lévesque, Stéphane: History in an Age of “Truth and Reconciliation”. In: Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 29, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-7043.

“Es ist beschämend, es ist ein hässlicher Teil unserer Geschichte”, sagt Daniel Elliot, ein indigener Nachfahre von Internats-Überlebenden.[1] “Ich will von der Kommission sehen, dass Geschichtsbücher neu geschrieben werden, so dass andere Generationen nicht durch das Gleiche hindurchgehen müssen, was wir jetzt erleben, als ob es nie passiert wäre.”[2] Der kürzlich erschienene Bericht der kanadischen Kommission für Wahrheit und Versöhnung (TRC) ruft Bildungsinstitutionen dazu auf, unser System zu dekolonialisieren: “Die Art, wie wir unsere Kinder und uns selbst erziehen, muss sich ändern. Das Denken muss sich ändern.”[3]

Wie sollen wir Geschichtsunterricht indigenisieren?

Wie in anderen postkolonialen Staaten ist die Notwendigkeit, indigene Perspektiven in die kanadische Geschichte zu integrieren, längst überfällig. Aber wie soll es gemacht werden? Die Indigenisierung von Ausbildung ist immer noch ein sehr offenes Projekt. Während die meisten LehrerInnen und VerlegerInnen dabei sind, mehr Erzählungen über indigene Völker zu integrieren, herrscht weniger Konsens darüber, wie und warum wir diese unterrichten sollen.

Es geht nicht bloss um Inhalte. Mehr Geschichten über frühe Kontakte mit Europäern oder mehr Geschichten über Internatsschulen lösen die Probleme nur bedingt. Die größere Herausforderung bezieht sich auf die Essenz der Geschichte: Was zählt als historische Erzählung? Tatsächlich kommen die momentanen Anforderungen für mehr indigene Perspektiven genau zu einem Zeitpunkt auf, an dem historische Bildung zunehmend als kritische, wissenschaftsorientierte Auseinandersetzung mit der Vergangenheit verstanden wird.

Peter Seixas hat jüngst angemerkt, dass diese Form historischen Denkens mittlerweile eine zentrale Rolle in der Theorie und der Praxis von Schulen in Kanada spielt.[4] Sich an wissenschaftlichem Denken orientierend hat sich der Geschichtsunterricht allmählich vom patriotischem Geschichtenerzählen entfernt und fördert kritisches Denken, forschendes Lernen und die multiperspektivische Analyse von historischen Quellen.

Formen des indigenen Wissens unterrichten

Wissenschaftsorientierte Geschichte wurde für ihr Unvermögen kritisiert, indigene Perspektiven auf das Verhältnis von Vergangenheit, Gegenwart und Zukunft darzustellen. Indigene Gelehrte behaupten, dass westliche Historiographien – mit ihrer Betonung auf historische Beweise, menschliche Wirkung, Fortschritt und Modernität – indigene Verständnisse zeitlicher Prozesse und der Prinzipien ökologischer Wissenssysteme außer Acht lassen.

Der Aboriginal-Pädagoge Michael Marker hat vier Eigenschaften von indigenen Formen des Wissens identifiziert: Erstens die zyklische Natur der Zeit und die Bedeutung mündlicher Erzählungen, die auf nicht-lineare Weise sich wiederholende Ereignisse verschmelzen; zweitens die zentrale Rolle der Beziehung zwischen Menschen, Landschaften und Tieren als Quellen für Wissen und Weisheit; drittens die Betonung der lokalen Landschaft, in der die Bedeutung der Zeit und des Orts enthalten ist und viertens indigene Narrative als physische und metaphorische Reisen, welche die Geschichten der Kolonialisation in Frage stellen.[5]

Aus der Sicht der indigenen Völker können westliche, evidenzbasierte Verfahren kein Verständnis für die Vergangenheit ermöglichen, weil sie einer “kolonialen Logik” verpflichtet seien. Vielmehr brauche es ein “indigenes historisches Bewusstsein”, das auf organisches Wissen vertraue, welches Menschen, Land und Natur verbinde.[6] “Unsere koloniale Erfahrung”, behauptet Linda Tuhiwai Smith,

“mache uns zu Gefangenen des Projekts der Moderne. […] Um die koloniale Perspektive unserer eigenen Geschichte zu transformieren, […] müssen wir Punkt für Punkt unsere Geschichte mit westlichen Augen erneut untersuchen.”[7]

Was können wir tun?

In einem kürzlich erschienenen Artikel fragt David Newhouse, ein aboriginaler Pädagoge: Können wir traditionelle indigene Erkenntnisverfahren für akademische Projekte nutzen?[8] Wir könnten hinzufügen: Ist es möglich, die heilige Ökologie von Tieren, Geistern sowie menschlichen Wirkungen und Lebenszyklen in die Geschichte Kanadas zu integrieren? Sind wissenschaftsorientierte und indigene Formen des Wissens überhaupt vereinbar? Zu diesen grundlegenden Fragen, die sich für verschiedene Kulturen und Nationen stellen, gibt es keine einfachen Antworten. Trotzdem, als kanadische LehrerInnen müssen wir ernsthaft über sie nachdenken, wenn wir zielstrebig die Empfehlungen der TRC implementieren.

LehrerInnen aufzufordern, tradiertes Wissen zu dekolonialisieren und mit einem indigenen historischen Bewusstsein unterrichten, ohne ihnen zuvor ein adäquates Verständnis zu vermitteln, ist das perfekte Rezept für eine Katastrophe. Wenn wir wollen, dass BürgerInnen – junge und erwachsene – mehr über die Geschichte der Internatsschulen und über indigene Formen des Wissens wissen, dann wird es nicht reichen, einfach noch mehr Geschichten in das bereits überfüllte Curriculum aufzunehmen.

Narrative Kompetenz

Geschichten – ob von vertrauenswürdigen HistorikerInnen oder von Ältesten – sind nicht die Vergangenheit. Sie bieten auch nicht ein vollständiges Bild der Vergangenheit. Viele Geschichten werden erzählt, sie können sich ergänzen oder widersprechen. Für einen kritischen Umgang mit Geschichte ist deshalb narrative Kompetenz notwendig.[9] Ohne eine Analyse der tieferen Strukturen von Narrativen kann das Erzählen von Geschichten leicht zur Mythenbildung verkommen. Eine zentrale Herausforderung des Unterrichts über die Geschichte der Internatsschulen liegt erstens darin, SchülerInnen dabei zu helfen, ein Verständnis aufzubauen, wie unterschiedliche indigene und nicht-indigene Narrative mit verschiedenen rhetorischen Mitteln aufgebaut sind. Zweitens geht es darum, die Kraft und den Stellenwert dieser unterschiedlichen Narrative für das tägliche Leben, die Kultur und die Identität zu bewerten. Drittens sollen SchülerInnen eigene verwertbare Narrative der kollektiven Vergangenheit produzieren.

Seixas behauptet deshalb zu Recht, dass westliche und indigene Historiographien eine einmalige Gelegenheit haben, in der gegenwärtigen Periode der Versöhnung zusammenzukommen.[10] Traditionelle mündliche Geschichtskultur und wissenschaftsorientierte Geschichtsschreibung sind dazu verwendet worden, manchmal in Kooperation, historische Wahrheiten über Erfahrungen in Internatsschulen aufzudecken, die sonst eventuell unbekannt geblieben wären.

KanadierInnen brauchen beide Formen der Geschichte – die disziplinäre und die indigene. Wir können nicht einfach die eine durch die andere im Namen der “Dekolonialisierung” ersetzen. Noch wichtiger ist es vielleicht, dass KanadierInnen wissen müssen, wie und wann sie diese unterschiedlichen Arten des Wissens einsetzen, um Versöhnung zu fördern und als BürgerInnen am demokratischen Leben in ihrem multikulturellen Land in vollem Umfang teilzunehmen.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future. Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Ottawa 2015.

- Marker, Michael: Teaching history from an Indigenous perspective. In: Clark, Penney (Hrsg.): New possibilities for the past. Shaping history education in Canada. Vancouver, BC 2011, S. 98–112.

- Seixas, Peter: Indigenous historical consciousness: An oxymoron or a dialogue? In: Carretero, Mario/Ascensio, Mikel/Rodríguez-Moneo, Marìa (Hrsg.): History education and the construction of national identities. Charlotte, NC 2012, S. 125–138.

Webressourcen

- . Where are the children? Healing the legacy of residential schooling. The Legacy of Hope Foundation, http://wherearethechildren.ca (letzter Zugriff: 21.7.2016).

_____________________

The author would like to thank Peter Seixas and Penney Clark for insightful comments on drafts of this version.

[1] Meine Überlegungen basieren auf verschiedenen Gespräche mit KollegInnen sowie konstruktiven Rückmeldungen zu Entwürfen dieses Texts von Penney Clark, Richard Maclure, Nicholas Ng-A-Fook and Peter Seixas.

[2] Indigene (oder aboriginal) Völker ist ein kollektiver Name für die UreinwohnerInnen Nordamerikas und ihre Nachkommen. Die kanadische Verfassung erkennt drei Gruppen von indigenen Völkern an: Erste Nationen (First Nations; ursprünglich “Indianer“ genannt), Mestizen (Métis) und Inuit. Mehr als 4 Millionen Menschen in Kanada identifizieren sich als Indigene, gemäss der 2011 durchgeführten Volkszählung.

[3] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Ottawa: Queen’s Printer for Canada, 2015, verfügbar unter http://nctr.ca/reports.php (letzter Zugriff: 31.7.2016).

[4] Seixas, Peter: “A Model of Historical Thinking, Educational Philosophy and Theory,” Educational Philosophy and Theory (2015). DOI: 10.1080/00131857.2015.1101363. Für wesentliche Details zu Konzepten des historischen Denkens, siehe http://historicalthinking.ca (letzter Zugriff: 31.8.2016).

[5] Marker, Michael: “Teaching history from an Indigenous perspective.” In: Clark, Penney (Hrsg.): New possibilities for the past: Shaping history education in Canada, Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 2011, S. 98–112.

[6] Siehe Donald, Dwayne: “On making love to death: Plains Cree and Blackfoot wisdom,” Equity Matters, February 1, 2011. http://www.ideas-idees.ca/blog/making-love-death-plains-cree-and-blackfoot-wisdom (letzter Zugriff: 31.8.2016); ders.: “Forts, curriculum, and Indigenous métissage: Imagining decolonization of Aboriginal-Canadian relations in educational contexts,” First Nations Perspectives: The Journal of the Manitoba First Nations Education Resource Centre, 2, 1 (2007), S. 1–24.

[7] Linda Tuhiwai Smith, zitiert in Marker, “Teaching history from an Indigenous perspective,” S. 110.

[8] Newhouse, David: “The meaning of Indigenizing in our universities,” CAUT Bulletin 63, 6 (2016), A2.

[9] Siehe meine früheren Blogbeiträge, u.a. Lévesque, Stéphane: “Going beyond ‘Narratives’ vs. ‘Competencies’: A model for understanding history education,” Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 12, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-5918; ferner: Körber, Andreas / Meyer-Hamme, Johannes: “Historical thinking, competencies, and their measurement”, In: Ercikan, Kadriye / Seixas, Peter (Hrsg.): New directions in assessing historical thinking, New York: Routledge, 2015, S. 89-101.

[10] Seixas, Peter: “Indigenous historical consciousness: An oxymoron or a dialogue?” In: Carretero, Mario / Ascensio, Mikel / Rodríguez-Moneo, Marìa (Hrsg.): History education and the construction of national identities, Charlotte, NC: Information Age, 2012, S. 125–138. Siehe auch Saul, John R.: The comeback, Toronto, ON: Viking, 2014; McGregor, Heather: “Exploring ethnohistory and Indigenous scholarship: What is the relevance to educational historians?” History of Education, 43(4), 431–449. DOI:10.1080/0046760X.2014.930184; und Anderson, Stephanie:, “The Stories Nations Tell: Sites of Pedagogy, Historical Consciousness and History Education,” Canadian Journal of Education (forthcoming), in Kürze verfügbar unter http://www.cje-rce.ca/index.php/cje-rce.

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

Photograph of students from Fort Albany Residential School reading in class overseen by a nun c 1945. From the Edmund Metatawabin collection at the University of Algoma., Wikimedia Commons (last accessed 14 September 2016).

Übersetzung

Jana Kaiser (kaiser at academic-texts .de)

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Levesque, Stéphane: Geschichte in der Ära von “Wahrheit und Aussöhnung”. In: Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 29, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-7043.

Copyright (c) 2016 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 4 (2016) 29

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-7135

Tags: Canada (Kanada), Colonial Legacy (Koloniales Erbe), Language: French, Postcolonial Perspectives, Reconciliation (Aussöhnung)

Very interesting and engaging post. It is at the core of public history. What needs to be decolonized is not that much the product than the process. Public History is also about changing the process (shared-authority and public participation).

It made me think of Amy Lonetree’s book on Decolonizing the Museum,[1] where she talks about the process of making history in museums.

Thank you for the post.

References

[1] Lonetree, Amy (2012). Decolonizing Museums. Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums. The University of North Caroline Press (http://uncpress.unc.edu/books/11761.html, last accessed 16 September 2016).

—————————–

Sehr interessanter und engagierter Beitrag. Es geht um den Kern der Public History. Was dekolonisiert werden muss, ist weniger das Produkt als der Prozess. In der Public History geht es auch die Veränderung des Prozesses (geteilte Verantwortung, öffentliche Teilnahme).

Der Beitrag hat mich an Amy Lonetrees Buch über die Dekolonisierung des Museums[1] erinnert, in dem sie Über den Prozess der musealen Geschichtsproduktion spricht.

Vielen Dank für diesen Beitrag.

Anmerkungen

[1] Lonetree, Amy: Decolonizing Museums. Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums. Chapel Hill 2012 (http://uncpress.unc.edu/books/11761.html, zuletzt am 16. September 2016).