Abstract:

Explanations for the failure to tackle the climate crisis increasingly focus on historical narratives and underlying ontologies. National histories have obscured the implications of the relationship between the exploitation of both labour and Nature for climate change. This paper explores these links via a transhistorical analysis of the Peruvian Amazon, revealing the importance of foregrounding indigenous histories and alternative ontologies to more sustainable forms of coexistence with Nature.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2022-19460

Language: English

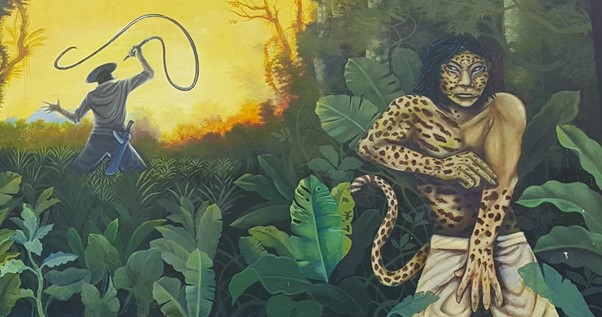

During field research in the Peruvian Amazon, an Indigenous activist showed me murals depicting indigenous perspectives on the horrors of the rubber boom of over a century ago. The images portray settler violence and subjugation; but also highlight indigenous resistance and knowledge, emphasising the natural and supernatural worlds. In the final mural (see above), for example, they assume animal form in order to access their power and become one with Nature.

The Amazon Through Time

As the murals emphasise, the exploitation of humans and Nature that began during the rubber boom continues to this day. This situation is enabled by historical narratives and ontologies that treat the rights, livelihoods and ecosystems of indigenous people as disposable. In the words of indigenous Bora lawyer Fanny Kuiru,

“Our people were treated horrifically. They were tortured and there were massacres. As a girl I grew up with this history … the rubber boom changed everything”.[1]

The worst atrocities took place in the Putumayo, present-day Colombia. The entity responsible – the Peruvian Amazon Company – was registered on the London Stock Exchange and had British directors. When word got out, the Anti-Slavery and Aborigines’ Protection Society pushed successfully for a Commission of Investigation to be led by Sir Roger Casement, the foremost human rights investigator of his day. Casement uncovered a system of de facto slavery which entrapped indigenous peoples with unpayable debts and coerced them to meet rubber quotas through the systematic use of torture, floggings and murder.[2] This caused the deaths of an estimated 40,000 Andokes, Boras, Huitotos and Ocainas, and deforested large areas.[3]

This situation was facilitated by ontologies that viewed racialised groups and Nature itself as “other” and, of course, lesser. This thinking was not confined to the rubber barons, but shared by a Peruvian state that introduced a law in 1898 opening up the Amazon to exploitation, disregarding the presence of indigenous inhabitants. Narratives of “civilisation” obscured the fact that indigenous knowledge of rubber trees and their qualities were central to the entire brutal, profit-driven system. This approach ran contrary to indigenous thinking that “everything is inter-related, humanity and Nature”, says Kuiru.[4]

Instead, the rubber was exported to meet industrial demand (particularly automobile manufacturing) in the US and Europe, which contributed significantly to the emissions that fed global warming. Despite an ensuing scandal, high global demand meant little action was taken to end this exploitation and abuse. What “saved” the Indigenous peoples from the rubber merchants was the development of synthetic rubber. The reprieve proved temporary, however: synthetic rubber is a by-product of oil, and growing demand soon brought a new phase of exploitation and environmental destruction.

Oil drilling displaced Indigenous groups and polluted so much of the surrounding land and water that today many people have heavy metals in their blood from eating toxic fish.[5] Pollution has severely damaged traditional livelihoods and food sources. As an Indigenous activist told me: “We are eating our last fish.” Desperate for a means of survival, many are forced to accept low-paid and dangerous work cleaning up oil spills, exposing them to toxic substances. The oil boom has also caused an upsurge in the trafficking of women and girls for sexual exploitation. Finally, the oil extracted is burned and ends up in the Earth’s atmosphere, further fuelling the climate crisis.

The Need for Alternative Thinking

The most recent summary report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) codified what for many of the poorest people is already a lived reality: that the climate crisis is endangering the planet, human and animal life, and in many cases adaptation is no longer possible.[6] According to UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres, the report presents an “atlas of human suffering”, and points to a “criminal” abdication of leadership.[7]

In seeking to account for this global failure to tackle the climate crisis, some are focussing on the role of historical narratives and ontologies. In particular, scholars point to the period of the Enlightenment and the influence of the thinking of philosophers such as Descartes. The idea of a duality between mind and matter and the separation of humans from Nature, has rendered it as a commodity to be conquered and possessed.[8]

In the context of the European conquest of the Americas, these abstractions became “practical instruments of domination”.[9] In contrast to the communal usage traditions of indigenous peoples, for Europeans, both land and Nature were conceptualised as sources of bounty to be managed and manipulated. As Latin American scholars argue, determining the “ontological status” of indigenous peoples to be one of “barbarians”, retrospectively justified their dispossession and exploitation.[10]

These philosophical debates, and the practices they enabled, have ongoing consequences for humanity. Firstly, this narrative established the moral purpose of empire, justifying slavery as “a school for civilisation”.[11] Under this guise, millions of Africans were enslaved and forced to labour in Caribbean sugarcane fields, where many died within five years. Indigenous peoples were subjected to other forms of servitude such as debt peonage, trapping them in conditions of “near slavery”.[12] Another method was the “mita”, an enormous operation of state labour that relocated indigenous people to work in dangerous conditions in the lucrative silver mines.

A second outcome is environmental. Labour exploitation was linked to the plunder of Nature, justified by narratives of “progress”. Indigenous peons cleared forests for European crops and animals; enslaved Africans cut down mangroves in the Caribbean; and coerced indigenous labourers felled trees for mines that poisoned water and soils with mercury.[13] The produce of this environmental and human exploitation made fortunes for Europeans – wealth that enabled the Industrial Revolution and drove greenhouse gas emissions. The close relationship between environmental destruction, climate change and contemporary slavery continues to his day, now typically justified on the basis of “development”.[14]

The third significant impact is ontological: the binary logic of cartesian dualism displaced and marginalised alternative ways of thinking. Dussel illustrates this point with the example of Felipe Guaman Poma, an indigenous writer.[15] His 1616 book, “The First New Chronicle and Good Government”, outlines Incan cosmovision, including rules governing the distribution of land and food, justice, and equitable gender roles. By contrast, Spanish rule brought about a level of misery and servitude previously considered impossible. Guaman Poma presents “a fierce critique” of colonialism and modern capitalism, which would “sacrifice the humans of the South and Nature” for profit.

Invisibilised for so long, the rapid acceleration of climate breakdown has finally revealed the need for alternative ontologies. For example, a recent UN report revealed that over 80 percent of indigenous-controlled territories in Latin America are forested, sequestering around 34 billions metric tons of carbon, and housing huge biodiversity.[16] Similarly, the IPCC’s latest report emphasises the importance of indigenous knowledge and territorial sovereignty. Welcome though this change is, however, research reveals a lack of critical engagement with indigenous ontologies and the historical contexts that have shaped them.[17]

Lessons Learned? A New Threat

Indigenous peoples such as those in the Peruvian Amazon, continue to face ongoing threats. In 2017, Peru announced a multi-million-dollar plan to create an Amazon Waterway linking the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, with the stated goal of bringing “development” and “connectivity” to inhabitants.[18] Many believe, however, that the project is primarily designed to facilitate international trade, including products like cocoa and soybeans, both strongly associated with labour exploitation and high rates of deforestation.

Local communities oppose the project on social and environmental grounds. Indigenous people believe the waterway will facilitate illicit activities, including land, drug and human trafficking. Additionally, the project proposes to dredge rivers, which they believe will increase drought and flooding due to climate change, and churn up toxic residues from oil spills. The impact could destroy fish stocks, threaten food security and displace communities. Indigenous activists therefore refer to the waterway as the “route of death”.

Diverging ontologies and historical narratives are centrally important to this issue. According to an indigenous activist, fishermen have long known that disturbing the river would bring “disaster”. That is no idle concern: research indicates that the Amazon rainforest is drawing ever-closer to an irreversible “tipping point” beyond which it would cease to absorb and begin to emit carbon.[19] A concrete example is Peru’s Amazon peatlands, which are potentially threatened by the waterway.

“For Us, it is a Threat”

Nevertheless, ingrained national development narratives and ontological prejudices mean that no attempt has been made to draw upon indigenous knowledge in planning this huge project.[20] Indeed, the Peruvian state has failed even to adequately consult with affected communities, in breach of its own laws. I witnessed this dynamic in an exchange between a well-intentioned local NGO officer and an indigenous Kukama Kukamiria leader. In response to the former’s confident assertion that the waterway would bring opportunity and development for his people, the indigenous leader stated simply: “For us, it is a threat”.

It threatens us all. Indigenous peoples no longer need saviours: hardened by the experiences of rubber and oil, they have developed tools for resistance. In response to the waterway, they have launched a legal challenge and harnessed international media to stall the project, for now. But in the much bigger battle for our shared home, there is an urgent need to take cognisance of indigenous ontologies and the historical contexts that shape them.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Dussel, Enrique. “Anti-Cartesian Meditations. On the Origins of the Philosophical Anti-Discourse of Modernity.” Journal for Cultural and Religious Theory 13, no. 1 (2014): 11-53.

- Hickel, Jason. Less is More. How degrowth will save the world. William Heinemann, 2020.

- Patel, Raj, and Jason W. Moore. A history of the world in seven cheap things. A guide to capitalism, Nature, and the future of the planet. Verso, 2018.

Web Resources

- Latin America Bureau. “Voices of Latin America” Project. https://lab.org.uk/voices/ (last accessed 27 March 2022).

- Anti-Slavery International. Website on Climate Change and Contemporary Slavery. https://www.antislavery.org/climate-change-modern-slavery/ (last accessed 27 March 2022).

- The Guaman Poma Website. http://www5.kb.dk/permalink/2006/poma/info/en/frontpage.htm (last accessed 27 March 2022).

_____________________

[1] Linda Etchart, “Indigenous Peoples and the Rights of Nature,” in Voices of Latin America, ed. Tom Gatehouse (Latin American Bureau, 2019), 102.

[2] Angus Mitchell, The Amazon Journal of Roger Casement (Lilliput Press, 1997).

[3] Alberto Chirif, Después Del Caucho (Lluvia Editores, 2017).

[4] Etchart, “Indigenous Peoples”, 102.

[5] Amnesty International, “Peru: A Toxic State: Violations of the Right to Health of Indigenous Peoples in Cuninico and Espinar, Peru” (2017), https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/amr46/7048/2017/en/ (last accessed 27 March 2022).

[6] “Sixth Assessment Report: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability” (IPCC, 2022), https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/ (last accessed 27 March 2022).

[7] António Guterres (UN Secretary-General), “Statement to the press conference launch of IPCC report”, UN WebTV, 2022, https://media.un.org/en/asset/k1x/k1xcijxjhp (last accessed 28 March 2022).

[8] Jason Hickel, Less Is More. How Degrowth Will Save the World (William Heinemann, 2020); Raj Patel, and Jason Moore, A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things. A Guide to Capitalism, Nature, and the Future of the Planet (Verso, 2018).

[9] Patel and Moore, History, 52.

[10] Enrique Dussel, “Anti-Cartesian Meditations. On the Origins of the Philosophical Anti-Discourse of Modernity,” Journal for Cultural and Religious Theory 13, no. 1 (2014): 11–53, here: 21.

[11] Patel and Moore, History, 62.

[12] Teresa Meade, History of Modern Latin America. 1800 to the Present (John Wiley & Sons, 2010), 79.

[13] Christopher Boyer, “Latin American Environmental History,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History (Oxford University Press, 2016).

[14] Chris O’Connell, “From a Vicious to a Virtuous Circle. Addressing Climate Change, Environmental Destruction and Contemporary Slavery,” 2021, https://www.antislavery.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/ASI_ViciousCycle_Report_web2.pdf (last accessed 27 March 2022).

[15] Dussel, “Anti-Cartesian“, 40.

[16] “Forest Governance by Indigenous and Tribal Peoples,” Food and Argricultural Organisation of the United Nations, 2022, https://www.fao.org/americas/publicaciones-audio-video/forest-gov-by-indigenous/en/ (last accessed 27 March 2022).

[17] James Ford, Laura Cameron, and Jennifer Rubis, “Including Indigenous Knowledge and Experience in IPCC Assessment Reports,” Nature Clim Change 6 (2016): 349–53, here: https://doi.org/doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2954.

[18] “Amazon Waterway. Good Business for the Country?” (Derecho, Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, 2020), https://dar.org.pe/archivos/brief_waterway.pdf (last accessed 27 March 2022).

[19] Thomas Lovejoy, and Carlos Nobre, “Amazon Tipping Point,” Science Advances 4, no. 2 (2018).

[20] “Amazon Waterway”.

_____________________

Image Credits

© The Author.

Recommended Citation

O’Connell, Chris: Indigenous Voices, Climate Change, and Modern Slavery. In: Public History Weekly 10 (2022) 2, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2022-19460.

Editorial Responsibility

Copyright © 2021 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 10 (2022) 2

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2022-19460

Tags: Climate Change (Klimawandel), Colonial Legacy (Koloniales Erbe), Exploitation, Indigenous Peoples (Indigene Völker)

To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

OPEN PEER REVIEW

Hearing the voices of the invaded

This brief paper reflecting upon the historical and contemporary injustices and exploitation experienced by the indigenous peoples of the Peruvian Amazon region makes an anguished case for interrupting western historical narratives of progress, imperial expansion and civilising missions and adopting a decolonised lens. History educators might usefully look to scholars such as Keynes (2019) exploring the possibilities of history education for transitional justice,[1] and Andreotti (2015), who proposes alternative approaches to assigning greater value to indigenous worldviews, for development of these ideas.[2]

The specific story of natural and human destruction deserves to be better known. Western demands for rubber and oil violently disregarded First Nations peoples’ wisdom and voice. The latest ‘development’ proposal of an Amazon Waterway in the name of facilitating international trade promises to continue a story of environmental vandalism and human dislocation. History educators have perhaps been too prepared to avert their eyes from the temporal dimensions of the Anthropocene.

Article 15 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, agreed in 2007, asserted a right ‘to the dignity and diversity of their cultures, traditions, histories and aspirations which shall be appropriately reflected in education’. E.P. Thompson, in ‘The Making of the English Working Class’, famously referred to his aspiration of rescuing working people left behind by the social and economic fallout of the industrial revolution ‘from the enormous condescension of posterity’. First Nations peoples and perspectives merit this same rescue mission. History educators can usefully turn their minds to how they might help to make this happen.

To name but three questions that seemed germane to this reviewer (See also Brett & Guyver, 2021)[3]:

In terms of ways in which educators might prompt ‘alternative ways of thinking’, I was persuaded by the author’s suggestion that there be a greater degree of focus upon contemporary texts such as Felipe Guaman Poma’s 1616 book outlining an indigenous Incan cosmovision, running counter to the narrative of Spanish colonial rule. In my own working context of Tasmania, an equivalent seminal text might be the dignified Petition sent by Aboriginal inhabitants of Van Diemen’s Land to Queen Victoria in February 1846, having been rounded up and transported to a remote island in the Bass Strait:

There is a powerful pathos in the puzzlement of betrayal.

The disciplines of consideration of historical evidence and of empathetic historical interpretation can assist in the interruption of settler-colonial assumptions. History may generally get to be written by victors, but there are ways in which the voices of the invaded should be heard and more respectfully acknowledged.

[1] Keynes, M. (2019). History Education for Transitional Justice? Challenges, Limitations and Possibilities for Settler Colonial Australia. International Journal of Transitional Justice, 13 (1), 113 – 133.

[2] Andreotti, V. (2016). Research and pedagogical notes: The educational challenges of imagining the world differently. Canadian Journal of Development Studies, 37(1), 101-112.

[3] See also Brett,P. & Guyver, R. (2021). Postcolonial history education: Issues, tensions and opportunities. Historical Encounters, 8 (2), 1-17.