Abstract: The (post-)industrial region of Upper Silesia continues to be associated with images of black and gray. Bynames for this area such as the “Ruhr district of the East” or the “black heart of Poland” still remain vivid in the minds of both Poles and Germans today. However, the modern reality is that Upper Silesia has long since managed to overcome and ultimately leave behind these outdated stereotypes. This especially holds true for Katowice/Kattowitz, the capital of the Upper Silesian Voivodeship. The city has started to make much progress towards establishing its future, particularly in the fields of high technology and culture. What role does the past play in this process of reinvention? Notwithstanding the omnipresence of the past in the city’s urban texture, Katowice prefers to look ahead instead of lingering behind.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-9502.

Languages: English, Deutsch

The (post-)industrial region of Upper Silesia continues to be associated with images of black and gray. Bynames for this area such as the “Ruhr district of the East” or the “black heart of Poland” still remain vivid in the minds of both Poles and Germans today. However, the modern reality is that Upper Silesia has long since managed to overcome and ultimately leave behind these outdated stereotypes. This especially holds true for Katowice/Kattowitz, the capital of the Upper Silesian Voivodeship. The city has started to make much progress towards establishing its future, particularly in the fields of high technology and culture. What role does the past play in this process of reinvention? Notwithstanding the omnipresence of the past in the city’s urban texture, Katowice prefers to look ahead instead of lingering behind.

No Palimpsest…

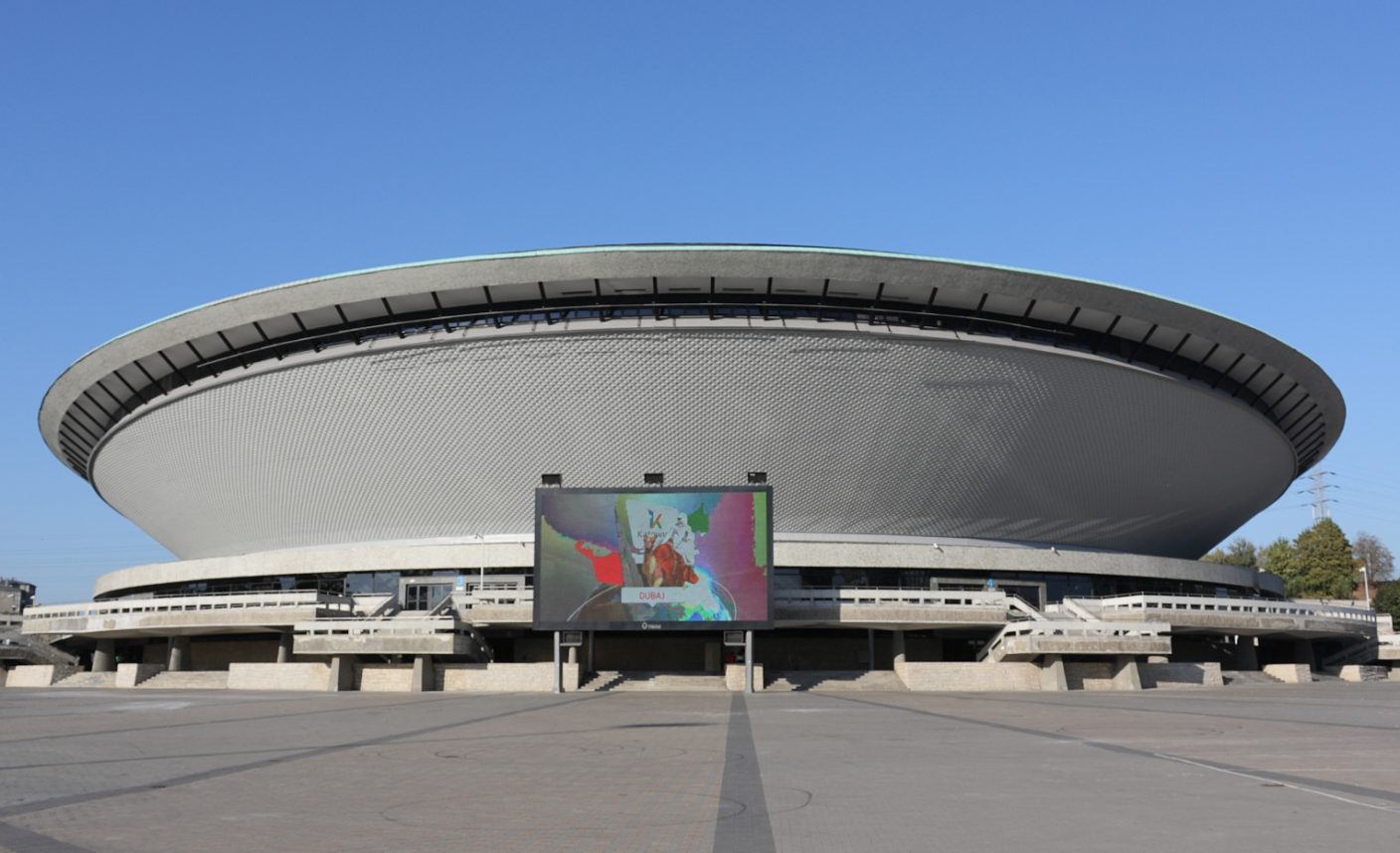

The complexity of the city’s past can still be felt in the urban environment today. Established along an east-west axis after 1865 and built with red clinker bricks, the architecture of Prussian Kattowitz remains largely unchanged in today’s city center. South of the town’s center, administrational, representational, and tenement buildings of the Polish interwar period can be found. These buildings were erected at a time when the region was split between Poland and Germany after the First World War, as the Polish city administration deliberately chose to implement modern architecture in order to demonstrate its sovereignty over the newly obtained territory. North of the Prussian city center, the socialist heartbeat of Katowice manifested itself in outstanding architectural innovations after 1945. Two of the city’s landmarks, the “Spodek” (a multi-purpose hall called the “Flying Saucer” due to its spectacular semicircular roof) and the “Superjednostka” (“Superblock” – the Upper Silesian answer to Le Corbusier) were built during this time.

The cityscape of Katowice is characterized by its lack of destruction, reconstruction and modification in regards to buildings – features of architectural heritage which are usually common in Central European cities. In Katowice, however, each era has added new architectural styles to the already existing ones. Even today, one can clearly identify the various architectural and urban features of the town’s development over the years. These features are reminiscent not only of the Polish-German rivalry in the fight for the city and region, but also of the period after 1945, when Upper Silesia formed the backbone of the socialist Polish economy.

…No Nostalgia

The juxtaposition of architectural features and historical eras in Katowice’s urban texture can, however, also lend credibility to the converse argument, namely that Katowice is a place of cultural discontinuity. Every historical turning point in the past has brought new initiatives to the forefront and has also brought about new urban textures with the aim of symbolically surpassing their predecessors. This constellation has created an ensemble of dissonant heritage which can only be fully appreciated in its entirety by those who are aware of the city’s complex past. Frankly, the continuity of Katowice’s history is expressed by its interminable resolve to break up with the past. Therefore, Katowice can hardly be regarded as a place of dialogue or mutual understanding – a label coined by the Lower Silesian capital Wroclaw/Breslau as early as the end of the 1990s. Making references to the past is a rather difficult and complicated endeavor in Katowice due to the lack of a commonly shared “golden era” with which everybody can identify.

Moving Away From the Past

Instead of constantly reminiscing about the past, Katowice is looking to the future. In the words of the renowned Polish art historian Ewa Chojecka, the city is characterized by an “instinct of modernity”,[1] a description which has come to practically embody the city center since 2014. After the city administration had proclaimed “culture” as the new guiding criteria for the city’s development, Katowice made the largest investment in culture in Poland since 1989, thereby creating a unique cultural space which is second to none in Poland. Since then, an unused inner-city, post-industrial area behind the “Spodek” was turned into what has been termed the “cultural axis.”

The Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra has a new venue there with outstanding acoustics; an international conference center combines nature and architecture with footpaths built on its spacious green rooftop; and the new home of the Silesian Museum uses the remains of a former coal mine as part of its exhibition space. Katowice has elaborated on its diverse urban texture with a newly designed vision for the future. This major investment was only made possible due to the significant characteristics of structural change after 1989. Rather than triggering a complete financial breakdown, these structural changes brought about a dynamic transformation process which has encouraged positive economic development in Katowice.

Dealing with Industrial Heritage

Which meaning does the past evoke in a city which is concentrating so much on its future? The industrial heritage of Katowice seems to be particularly contested because it is perceived as damaging the city’s aspirations to become a cultural metropolis. This is even more striking when one considers that the neighboring city of Zabrze has been preserving and marketing its industrial heritage for a long time. Katowice, meanwhile, can only point to a few instances where it has adopted a more cautious and responsible approach towards its industrial heritage. The new home of the Silesian Museum can be considered as one of the most successful examples. However, form and content do not fall in place entirely. In one performative act, the visitors enter the exhibition by going downstairs to the underground level. Initially, the beginning of the exhibition was to feature aspects of regional industrialization and a quotation by the German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. This caused public and political controversy, and the exhibition, which had not yet been completed, was cancelled in 2012, because the concept was perceived as highlighting the German influence in Upper Silesia too much.[2] The exhibition which has been on display since 2015 adopts a narrative more biased towards Poland. A multimedia entrance scene which refers to the political turning point of 1989 is followed by an exhibition room about the Middle Ages.

A similar development could be observed when the Giszowiec/Gieschewald settlement was reassessed during Katowice’s application for the title of “European Capital of Culture.” The worker’s settlement Gieschewald was built by the Berlin-based architects Georg and Emil Zillmann on the outskirts of then-German Kattowitz in the first decade of the twentieth century. For the application process, the city was described as being the “first Polish garden-city.”[3] This was necessary because the application and its inherent future-oriented concept of Katowice as a “garden city” required a historical reference, which was found in Gieschewald. Therefore, the discourse on the past did not seemingly permit references to Gieschewald as an architecturally sophisticated worker’s settlement from the German period of Katowice.

_____________________

Further Reading

- “Śląsk/Silesia,” Herito. Heritage, Culture & the Present 1 (2016).

- Oslislo-Piekarska, Zofia. Nowi Ślązacy: Miasto, dizajn, tożsamość [New Silesia: City, Design, Identity]. Katowice: Akademia Sztuk Pięknych w Katowicach, 2015.

- Tomann, Juliane. Geschichtskultur im Strukturwandel: Öffentliche Geschichte in Katowice nach 1989. Oldenbourg: De Gruyter, 2017.

Web Resources

- Katowice: Miasto Ogrodów [Katowice: The Garden City]. http://cityofgardens.eu/ (last accessed on 6 June 2017).

- “Katowice International Conference Centre / JEMSarch daily,” ArchDaily, December 4, 2015, http://www.archdaily.com/778138/katowice-international-conference-centre-jems/565e5c32e58ece20b40001c0-katowice-international-conference-centre-jems-image (last accessed on 6 June 2017).

_____________________

[1] Łukasz Galuszek, “O sztuce, której nie było [About art, which never existed]. Interview with Ewa Chojecka,” Herito 1 (2010): 70-86.

[2] These are the opinions of Vice Voivode Piotr Spyra. See Martin Sander, “Das Gespenst des Deutschtums,” Deutschlandfunk, October 3, 2012 (radio broadcast). In Katowice, the reorientation of the Silesian Museum has been a major topic.

[3] Office of Applications for the European Capital of Culture, eds., “Katowice Miasto Ogrodów” [Garden City Katowice] (city map). Katowice: 2011.

_____________________

Image Credits

Katowice Spodek-Nowa elewacja © WhiskeySix (2011) via Wikimedia Commons.

Recommended Citation

Tomann, Juliane: Urban Images–An Industrial Metropole Reinvents Itself. In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017 ) 23, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-9502.

Oberschlesien – schwarz bis grau sind die Assoziationen, die diese (post)industrielle Region bis heute hervorruft. Das “Ruhrgebiet des Ostens” oder das “schwarze Herz Polens” sind als Zuschreibungen fest auf der mentalen Landkarte von Polen, aber auch von Deutschen verankert. Die oberschlesische Realität hat diese überkommenen Stereotype jedoch längst hinter sich gelassen. Vor allem die Hauptstadt der Woiwodschaft, Kattowitz/Katowice, ist auf der Überholspur in Richtung Zukunft – getragen von High-Tech und Kultur. Und die Vergangenheit? Obwohl sie omnipräsent ist in ihrer urbanen Textur, blickt die Stadt lieber nach vorn als zurück.

Kein Palimpsest…

Wie vielschichtig die Vergangenheit der Stadt war, kann man bis heute im Stadtraum in komprimierter Weise “lesen”. Das entlang einer West-Ost-Achse nach 1865 angelegte, aus roten Klinkern gebaute preußische Kattowitz befindet sich nach wie vor fast unverändert im heutigen Stadtzentrum. Südlich davon grenzen die Verwaltungs-, Repräsentations- und Wohnbauten der polnischen Zwischenkriegszeit an, als Oberschlesien zwischen Polen und Deutschland geteilt war. Der Stil der Moderne sollte die Souveränität Polens über das neu gewonnene Gebiet suggerieren. Nördlich davon schlug nach 1945 das sozialistische Herz der Stadt, mit seinen Markenzeichen “Spodek” (Mehrzweckhalle, aufgrund ihrer spektakulären Architektur “Untertasse” genannt) und “Superjednostka” (“Superblock” – die oberschlesische Antwort auf Le Corbusier).

Im Gegensatz zur Mehrheit mitteleuropäischer Städte ist Katowices Stadtbild daher weniger stark von Zerstörung, Wiederaufbau oder Umbau geprägt. Es weist vielmehr allen drei städtebaulichen Einheiten einen Platz zu. Die urbane Textur spiegelt die deutsch-polnische Rivalität um Stadt und Region symbolisch ebenso wider wie die wichtige Entwicklungsperiode nach 1945, als Oberschlesien das wirtschaftliche Rückgrat des sozialistischen Polens war.

… keine Nostalgie

Die räumliche Nähe von Bauabschnitten und historischen Epochen im städtischen Raum lässt jedoch auch den Umkehrschluss zu: Katowice ist ein Ort kultureller Diskontinuität. Jeder Wendepunkt in der Vergangenheit brachte neue AkteurInnen und stadträumliche Lösungen, die die Bedeutung der vorherigen Epoche symbolisch überbieten und in den Schatten stellen sollten. Entstanden ist aus dieser Konstellation ein Ensemble von dissonant heritage, das sich heute nur denjenigen in Gänze erschließt, die um die komplexe Vergangenheit der Stadt wissen. Zugespitzt könnte man behaupten, die Kontinuität der Stadtgeschichte liegt vor allem im fortgesetzten Willen zum Bruch mit der Vergangenheit.

Katowice ist daher schwerlich ein Ort des Dialoges oder der gegenseitigen Verständigung – ein Label, das sich etwa die Nachbarn in der niederschlesischen Hauptstadt Wrocław/Breslau schon Ende der 1990er Jahre auf die Fahnen geschrieben haben. Die inhärenten Konfliktlinien machen den Bezug auf die Vergangenheit schwierig, es fehlt eine “goldene Ära”, ein für alle gleichermaßen unbestrittener und positiv besetzter Referenzpunkt.

Abschied von der Vergangenheit

Anstelle von nostalgischer Rückwärtsgewandtheit sei Katowice vielmehr von einem “Instinkt der Moderne” geprägt, so die bekannte Kunsthistorikerin Ewa Chojecka.[1] Was das konkret bedeutet, lässt sich seit 2014 im Katowicer Stadtzentrum bestaunen. Nachdem die Stadtverwaltung bereits im Jahr 2005 “Kultur” zur neuen Leitlinie für die Stadtentwicklung erhoben hatte, leistete sich Katowice die größte Kulturinvestition in Polen nach 1989, ein Solitär in der polnischen Kulturlandschaft: Eine “Kulturachse” erschließt seither ein innerstädtisches postindustrielles Areal hinter dem “Spodek”, das größtenteils brachlag.

Das Polnische Radiosymphonieorchester hat hier einen neuen Sitz mit hervorragender Akustik erhalten, ein internationales Konferenzzentrum verbindet Architektur und Natur mit begrünten Spazierwegen auf dem weitläufigen Dach und das neue Schlesische Museum nutzt die architektonischen Überreste einer ehemaligen Grube. Katowice hat eine neue Schicht urbaner Textur erhalten, die der Stadtlandschaft erneut einen Zukunftsentwurf eingeschrieben hat. Finanziert werden konnte diese Großinvestition, da der Strukturwandel in Oberschlesien nach 1989 keinen ungebremsten ökonomischen Niedergang mit sich brachte, sondern einen dynamischen Transformationsprozess, der der Stadt trotz der Umstrukturierung eine insgesamt positive wirtschaftliche Entwicklung bescherte.

Umgang mit dem industriellen Erbe

Welche Bedeutung hat nun die Vergangenheit, wenn alle Zeichen in die Zukunft weisen? Besonders das Industrieerbe scheint in Katowice umstritten, liegt es doch quer zur Zukunftsvision einer Kulturmetropole. Während die Nachbarstadt Zabrze ihre industriellen Hinterlassenschaften schon lange erfolgreich konserviert und vermarktet, gibt es in Katowice nur wenige Beispiele, wo mit den Überresten von Industrie und Bergbau auf behutsame und verantwortungsvolle Weise umgegangen wird. Zu den gelungenen Beispielen gehört der Neubau des Schlesischen Museums. Es gibt jedoch Dissonanzen zwischen Inhalt und Form. In einem performativen Akt steigen die BesucherInnen hinab in die unterirdischen Welten der Ausstellung. Deren ursprüngliche Konzeption sah vor, die dort seit 2015 präsentierte Regionalgeschichte mit der Industrialisierung und einem Zitat Goethes beginnen zu lassen. Das war politisch nicht vermittelbar und die Ausstellung wurde 2012 noch im Planungsstadium mit dem Argument gekippt, diese Perspektive sei zu deutsch.[2] Die gegenwärtige Schau erzählt die Geschichte Oberschlesiens in einem national-polnischen Rahmen: Nach einer multimedialen Eingangssequenz, die an das Jahr 1989 erinnert, beginnt die eigentliche Narration im Mittelalter.

Ähnliches geschah mit der aus deutscher Zeit stammenden und an die Essener Margarethenhöhe erinnernden Arbeitersiedlung Giszowiec/Gieschewald, die im ersten Jahrzent des 20. Jahrhunderts von den Berliner Architekten Georg und Emil Zillmann am Stadtrand des damaligen deutschen Kattowitz erbaut worden war. Diese Arbeitersiedlung wurde während der Bewerbung um den Titel “Kulturhauptstadt Europas” kurzerhand zur “ersten polnischen Gartenstadt” erklärt.[3] Die Bewerbung Katowices unter dem Motto “Gartenstadt” brauchte den Bezug zu Gieschewald, um einen historischen Referenzpunkt zu ihrem Zukunftsprojekt der “Gartenstadt” zu schaffen. Die Möglichkeit, Gieschewald als das zu benennen, was es war, eine zu deutscher Zeit errichtete, architektonisch hochwertige Arbeitersiedlung, ließ der Vergangenheitsdiskurs in der Stadt jedoch anscheinend nicht zu.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- [o.A.]: Śląsk/Silesia. In: Herito. Heritage, Culture & the Present 1 (2016).

- Zofia Oslislo-Piekarska: Nowi Ślązacy. Miasto, dizajn, tożsamość [Neue Schlesier. Stadt, Design, Identität]. Katowice 2015.

- Juliane Tomann: Geschichtskultur im Strukturwandel. Öffentliche Geschichte in Katowice nach 1989. Oldenbourg 2017.

Webressourcen

- “Katowice – the garden city”: http://cityofgardens.eu/ (letzter Zugriff am: 06.06.2017).

- Architekturblog Arch Daily zu Objekten in Katowice: http://www.archdaily.com/778138/katowice-international-conference-centre-jems/565e5c32e58ece20b40001c0-katowice-international-conference-centre-jems-image (letzter Zugriff am: 06.06.2017).

_____________________

[1] Łukasz Galuszek: O sztuce, której nie było [Über Kunst, die es nicht gab]. Interview mit Ewa Chojecka. In: Herito 1 (2010), S. 70-86, hier S. 79.

[2] So sah es etwa der Vizewoiwode Piotr Spyra, nachzuhören bei Martin Sander: Das Gespenst des Deutschtums. In: Deutschlandfunk vom 3.10.2012. In Kattowitz wird um die Neuausrichtung des Schlesischen Museums gestritten.

[3] Vgl. Stadtplan “Katowice Miasto Ogrodów” [Gartenstadt Katowice]. Büro der Kulturhauptstadtsbewerbung (Hrsg.). Katowice 2011.

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

Katowice Spodek-Nowa elewacja © WhiskeySix (2011) via Wikimedia Commons.

Übersetzung

Stefanie Svacina and Paul Jones (paul.stefanie@outlook.at)

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Tomann, Juliane: Stadtbilder – Eine alte Industriemetropole erfindet sich neu. In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 23, DOI:dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-9502.

Copyright (c) 2017 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 5 (2017) 23

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-9502

Tags: Cultural Heritage (Kulturerbe), Katowice, Poland (Polen), Urban History (Stadtgeschichte)

It is fascinating to read how different the historical culture of the ‘Ruhr of the East’ is to the (actual) Ruhr of the West, and how differently industrial heritage has been constructed and appropriated as related to their regional identities.

In the Ruhr cities, the industrial past is almost inescapable, a very thick time layer that in many ways dominates the historical narratives across the the region. Voices that wish to ‘draw a line’ under the industrial past can be heard, yet there seems to be a strong consensus about the continuation of the industrial past in the future. As much as the forward-looking Ruhr once appeared as ‘a land without history’, since the late 1960s the history of industrial infrastructure has effectively provided for future visions (with many hopeful stakeholders today yearning for even greater recognition and an enlargment of the Ruhr’s UNESCO world heritage). Polish migration to the Ruhr is, by the way, an integral part of its industrialised historical culture and the related multicultural self-image, and there are current efforts to even foster the public memory of labour migration and the so-called Ruhrpolen.

I have always imagined Upper Silesia to be incredibly similar to the Ruhr, but the regional identity repertoire and historical culture seems so much more complex as this article is suggesting. I am particulary struck by the fact that there is such a great dicrepancy between the cities of the region. It seems there are conflicting sets of national heritage that impede representations of industrial heritage in Kattowice. The contested heritage of the the communist era adds to this complexity, having shaped not only processes of deindustrialisation but, perhaps more importantly, also the structures of collective memory of labour (even if the urban structures of the two Ruhrs are so congenial).

Thankfully, history and heritage are always changing and subject to dispute. Hopefully their uses in Kattowice will be of a more cosmopolitan kind in the future. In any case, I am now even more interested in this region than I had been before reading this intriguing article, and shall look up the train schedule…