Abstract: The hand-wringing about narrative in history and fiction that followed Hayden White’s challenges to historiography is now largely over. What has replaced it is a broad consensus about three propositions. While putting certain issues to rest, this consensus raises a question: how shall we articulate a concept of plausibility of historical narratives as a way to assess their adequacy and to teach students to do so? Jörn Rüsen offers a starting point with his definition of ‘Triftigkeit’.

DOI: Krzysztof Ruchniewicz.

Languages: English, Deutsch

The hand-wringing about narrative in history and fiction that followed Hayden White’s challenges to historiography is now largely over. What has replaced it is a broad consensus about three propositions. While putting certain issues to rest, this consensus raises a question: how shall we articulate a concept of plausibility of historical narratives as a way to assess their adequacy and to teach students to do so? Jörn Rüsen offers a starting point with his definition of ‘Triftigkeit’.[1]

A Consensus on three Propositions

1) Historical narratives and the past itself are different kinds of things. Accordingly, a narrative’s “concordance” with “the past” is not a workable basis for judging it.[2] We cannot speak of the vanished “past” at all except through narratives. Arthur Danto captured the idea: “Not being what it is a picture of is not a defect in pictures, but a necessary condition for something to be a picture at all.”[3]

2) Multiple narratives are possible for any set of events, centring different actors, using different theoretical lenses, employing different periodization. There is no such thing as a “perfect” history that encompasses all aspects of a particular piece of the past (e.g., World War II). There are too many aspects, vantage points, scales, etc.[4]

3) All narratives can be criticized for their plausibility; some lie entirely outside of the realm of plausible history.

How, then, as I asked above, shall we articulate a concept of plausibility that is useful for assessing the adequacy of historical narratives?

Dimensions of Rüsen´s Triftigkeit

Andreas Körber’s English-language exposition of Jörn Rüsen’s Triftigkeit explores three dimensions of plausibility: empirical, normative, and narrative.

The “empirical plausibility” of a narrative is achieved by listing multiple sources and providing analyses of their relevance and utility. Empirical plausibility has already been well explored in English, though not under that term, particularly in the work of Sam Wineburg and his students. Chauncey Monte-Sano provides lists of indicators for students’ historical writing in factual and interpretive accuracy, and persuasiveness, sourcing, corroboration and contextualization of evidence.[5] “Empirical plausibility” is more intuitively understood in English as “evidentiary plausibility.”

Rüsen’s second dimension, “normative plausibility,” looks to the audience or readership for recognition and acceptance of the norms and values underlying the account. Of course, in settings where potential audiences maintain deeply divided normative commitments, it may be less helpful, and those are precisely the settings where educators most urgently need powerful guidelines. In the Canadian model of historical thinking, the “ethical dimension” ventures into comparable terrain.[6] It focuses, however, not on the readership’s norms and values (per Rüsen), but rather on the historian’s difficult negotiation between the norms and values of historical actors from another time and the judgments of their actions according to contemporary standards in the present. The normative plausibility of a historical narrative, in this line of thinking, is the result of a successful interpretation, between sensitivities of the past and values of the present, informing everything from collective identities to forms of commemoration and restorative justice. Rüsen’s normative plausibility is entirely complementary to this conception.

Rüsen’s third dimension, “narrative plausibility,” depends upon “the patterns and logics of narrative construction (e.g. the ideas of typical principles of human perception, behaviour and action…).” But these are exactly what historians seek to historicize! On the other hand, historians must assume some transhistorical notions of how humans feel and behave (e.g., in the face of injury, hunger, love) when they seek to understand people from past eras. This conundrum is extensively explored in the English language literature under various categories including “perspective-taking” in the Canadian model, “rational understanding” in the British, and “empathy” in the Australian.[7] In English, however, it is problematic to assign “narrative” plausibility to this dimension alone. I propose that this dimension be called “empathetic plausibility” so that “narrative plausibility” can be reserved as an overarching concept for all of the ways that a narrative interpretation can be judged for its validity.

The Canadian Model of historical thinking Concepts as Dimensions of Plausibility

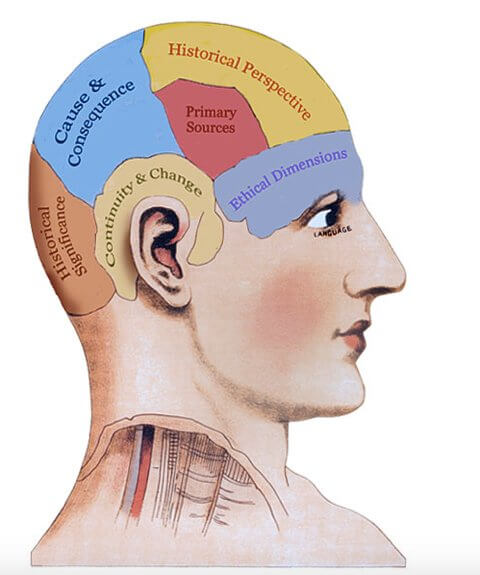

In sum, the major concerns of the three dimensions of plausibility in Rüsen’s scheme, as explained by Körber in English, are not unknown in the Anglophone history education literature. In the Canadian model, they are related specifically to the historical thinking concepts of primary source evidence, the ethical dimension, and perspective-taking. The fact that Rüsen’s dimensions map so well onto three of the six concepts opens the question of whether any of the remaining concepts in the Canadian scheme can also be viewed as contributions to what I will now call (as the overarching term, pace Rüsen) narrative plausibility.

Certainly, the fourth of the six historical thinking concepts, cause and consequence, suggests the criterion, “causal plausibility”: to what degree do the conditions and events assembled as causes in a particular narrative convincingly determine the events and conditions identified as consequences? Given the centrality of causality in establishing coherence in historical narratives, the case for “causal plausibility” as a key criterion in constructing and analyzing historical narratives is compelling.

Continuity and change are similarly fundamental to narrative interpretation. The chronological order of events, convincing designations of beginnings, endings, and periods, coherently linked with assessments of development, devolution, progress and decline: these are basic elements of a coherent narrative, contributing to sense-making. This dimension might be called “temporal plausibility.”

| Historical thinking concept (Canadian model) | Dimension of narrative plausibility |

| Significance | See note. [8] |

| Evidence | Evidentiary plausibility |

| Continuity and change | Temporal plausibility |

| Cause and consequence | Causative plausibility |

| Perspective taking | Empathetic plausibility |

| The ethical dimension | Normative plausibility |

This is not to say that the Canadian model of historical thinking concepts has already dealt with the problems of the plausibility of interpretive narratives. Rather, a focus on the construction and critique of narratives adds a crucial new aspect to the concepts. The Canadian model has heretofore omitted discussion of how these historical thinking concepts (and perhaps “significance” as well) can contribute to the construction and critique of narrative interpretations. Rüsen’s terminology—the multidimensional criteria of plausibility—offers a starting point for understanding how this works. As these criteria are developed in English, history educators will have some powerful tools for teaching students to assess narrative plausibility in the classroom.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Clark, Penney, and Alan Sears. “Fiction, History and Pedagogy: A Double-Edged Sword.” Journal of Curriculum Studies, 5 October 2016, doi: 10.1080/00220272.2016.1238108.

- Körber, Andreas. “Translation and Its Discontents II: A German Perspective.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 48, no. 4 (August 2016): 440-56.

- Seixas, Peter, and Tom Morton. The Big Six Historical Thinking Concepts. Toronto: Nelson Education, 2013.

Web Resources

- The Historical Thinking Project (Canada) http://

historicalthinking.ca/ (last accessed 6 December 2016) - Jocelyn Létourneau (Quebec, Canada) https://

jocelynletourneau.com (last accessed 6 December 2016).

_____________________

[1] For further development of the ideas in this article, see Peter Seixas, “Narrative Interpretation in History (and Life),” in Begriffene Geschichte ‒ Geschichte Begreifen. Essays in Honour of Jörn Rüsen, ed. Holger Thünemann (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2016), and “Epilogue: Teaching Rival Histories, in Search of Narrative Plausibility,” in International Perspectives on Teaching Rival Histories, ed. Henrik Åström-Elmersjö, Anna Clark, and Robert Parkes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, forthcoming).

[2] Andreas Körber, “Translation and Its Discontents II: A German Perspective,” Journal of Curriculum Studies 48, no. 4 (2016), p. 449. Körber’s explication of Rüsen’s conception of Triftigkeit, or plausibility, provides the basis for this article.

[3] Arthur C. Danto, Narration and Knowledge (Including the Integral Text of Analytical Philosophy of History) (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), p. 114.

[4] Interestingly, as recently as 1985, with the publication of Danto, pp. 114ff, such a consensus apparently did not exist.

[5] Chauncey Monte-Sano, “Disciplinary Literacy in History: An Exploration of the Historical Nature of Adolescents’ Writing,” The Journal of the Learning Sciences 19, no. 4 (2010), p. 548.

[6] Peter Seixas, A model of historical thinking. Educational Philosophy and Theory. 25 October 2015, doi:10.1080/00131857.2015.1101363 (last accessed 28 October 2016).

[7] Tyson A. Retz, “The History and Function of Empathy in Historical Studies: Re-Enactment and Hermeneutics” (University of Melbourne, 2016).

[8] In the Canadian model, historical significance is a question about how particular events or people fit within larger narratives: they achieve significance through their part in a larger story that is meaningful for its audiences today. To introduce “significance” as a dimension of plausibility for the larger narratives themselves might introduce confusion about the earlier definition of historical significance.

_____________________

Image Credits

Historical Thinking Concepts Image © Peter Seixas, 2016.

Recommended Citation

Seixas, Peter: In Search of narrative Plausibility. In: Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 41, DOI:dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-7853

Das Händeringen über das Narrativ in Geschichte und Erzählliteratur nach den an die Historiographie gerichteten Herausforderungen Hayden Whites ist jetzt größtenteils vorbei. Es ist durch einen breiten Konsens über drei Vorschläge ersetzt worden. Auch wenn dieser Konsens den Streit über bestimmte Sachverhalte beigelegt hat, bleibt noch eine Frage: wie sollen wir ein Konzept der Triftigkeit von historischen Narrativen als eine Art, ihre Angemessenheit einzuschätzen, artikulieren und Studierende unterrichten, dies zu tun? Einen Ausgangspunkt bietet Jörn Rüsen mit seiner Definition von Triftigkeit.[1]

Ein Konsens über drei Vorschläge

1) Historische Narrative und die Vergangenheit selbst sind unterschiedliche Dinge. Deshalb ist die “Konkordanz” eines Narrativs mit “der Vergangenheit“ nicht eine geeignete Basis für seine Bewertung.[2] Wir können von der verschwundenen “Vergangenheit“ gar nicht außer durch Narrative sprechen. Arthur Danto hat die Idee erfasst: “Nicht das zu sein, was es abbildet, ist nicht ein Mangel von Bildern, sondern ein notwendiger Zustand, um überhaupt ein Bild zu sein.”[3]

2) Mehrere Narrative sind für jede Sammlung von Ereignissen möglich, die unterschiedliche Akteure in den Mittelpunkt stellen, unterschiedliche theoretische Linsen verwenden, unterschiedliche Periodisierung gebrauchen. Es gibt keine “perfekte” Geschichte, die alle Aspekte eines bestimmten Stückes der Vergangenheit (z.B. den 2. Weltkrieg) umfasst. Da sind zu viele Aspekte, Blickwinkel, Skalierungen usw.[4]

3) Die Triftigkeit sämtlicher Narrative kann kritisiert werden; manche liegen ganz außerhalb des Bereichs der plausiblen Geschichte.

Wie denn, wie ich oben fragte, sollen wir ein Konzept der Plausibilität artikulieren, das für die Bewertung der Angemessenheit von historischen Narrativen nützlich ist?

Die Dimensionen von Rüsens Triftigkeit

In seiner englischsprachigen Darstellung von Jörn Rüsens Begriff der Triftigkeit untersucht Andreas Körber drei Dimensionen der Plausibilität: empirisch, normativ und narrativ.

Die “empirische Plausibilität“ eines Narrativs wird durch das Auflisten von mehreren Quellen und die Analyse ihrer Relevanz und Brauchbarkeit erreicht. Empirische Plausibilität ist schon im Englischen gut untersucht worden, wenn auch nicht unter diesem Begriff, insbesondere durch die Studien von Sam Wineburg und seiner StudentInnen. Chauncey Monte-Sano hat Listen von Indikatoren bereitgestellt, die für das Schreiben über Geschichte durch SchülerInnen relevant sind: faktische und interpretative Genauigkeit, Überzeugungskraft, Umgang mit Quellen, Bestätigung und Kontextualisierung von Beweisen.[5] Im Englischen wird “empirische Plausibilität“ intuitiv eher als “auf Nachweisen beruhende Plausibilität“ verstanden.

Rüsens zweite Dimension – “normative Plausibilität“ – sucht vom Publikum oder von der Leserschaft Anerkennung und Annahme der Normen und Werte, die dem Bericht zugrunde liegen. Natürlich kann das in Fällen, in dem das mögliche Publikum sehr weit auseinanderliegende normative Ansichten hegt, wenig hilfreich sein, aber es sind genau solche Einstellungen, für die PädagogInnen am dringendsten kraftvolle Richtlinien brauchen. Im kanadischen Modell des historischen Denkens wagt sich die “ethische Dimension“ auf ein vergleichbares Terrain.[6] Allerdings richtet es sich nicht auf die Normen und Werte der Leserschaft (wie bei Rüsen), sondern auf die für HistorikerInnen schwierigen Verhandlungen zwischen den Normen und Werten historischer Akteure aus anderen Zeiten und die Bewertung ihrer Handlungen im Einklang mit den zeitgemäßen Standards von heute. Nach dieser Art des Denkens ist die “normative Plausibilität“ das Ergebnis einer erfolgreichen Interpretation zwischen den Befindlichkeiten der Vergangenheit und den gegenwärtigen Werten, die alles von kollektiven Identitäten bis zu Arten von Gedenken und ausgleichender Justiz (restorative justice) informiert. Die normative Plausibilität Rüsens ist völlig komplementär zu dieser Auffassung.

Die dritte Dimension Rasens – “narrative Plausibilität“ – ist von “den Mustern und Logiken der Konstruktion von Narrativen (z.B. typische Prinzipien der menschlichen Wahrnehmung, des Verhaltens und des Handelns …)“ abhängig. Aber genau das wollen die HistorikerInnen historisieren! Auf der anderen Seite müssen HistorikerInnen einige transhistorische Annahmen darüber treffen, wie Menschen fühlen und sich verhalten (z.B. bei Verletzungen, Hunger, Liebe), wenn sie Menschen aus vergangenen Epochen zu verstehen versuchen. Dieses Rätsel ist in der englischsprachigen Literatur eingehend untersucht worden unter einer Reihe von Kategorien, unter anderem “Perspektivenübernahme” (perspective-taking) im kanadischen Modell, “rationales Verstehen“ (rational understanding) im englischen und “Empathie“ (empathy) im australischen Modell.[7] Allerdings ist es in der englischen Sprache problematisch, “narrative” Plausibilität allein dieser Dimension zuzuordnen. Ich schlage vor, diese Dimension “empathische Plausibilität“ zu nennen, um “narrative Plausibilität“ für ein allumfassendes Konzept zu reservieren, mit dem eine narrative Interpretation bezüglich ihrer Validität umfassend beurteilt werden kann.

Das kanadische Modell für Konzepte des historischen Denkens als Dimensionen der Plausibilität

Zusammengefasst sind die Hauptanliegen der drei Dimensionen der Plausibilität in Rüsens Schema, wie Körber sie auf Englisch erklärt, in der anglophonen Literatur zu Geschichtsunterricht nicht unbekannt. Im kanadischen Modell gehören sie spezifisch zu den folgenden Konzepten des historischen Denkens: primäre Quellenbeweise, die ethische Dimension und Einnehmen einer Perspektive. Die Tatsache, daß die Dimensionen Rüsens so passend drei der sechs Konzepte abbilden, führt zu der Frage, ob die restlichen Konzepte im kanadischen Schema auch als Beiträge zu dem, was ich jetzt (als übergreifender Begriff, mit allem Respekt gegenüber Rüsen) narrative Plausibilität nennen möchte, angesehen werden können.

Gewiss weist das vierte der sechs Konzepte für historisches Denken – Ursache und Konsequenz – auf das Kriterium “kausale Plausibilität“ hin: inwieweit bestimmen die Umstände und Ereignisse, die als Ursachen in einem bestimmten Narrativ zusammengefasst sind, in überzeugender Weise die Ereignisse und Umstände, die als Konsequenzen identifiziert wurden? Angesichts der zentralen Rolle der Kausalität beim Nachweisen von Kohärenz in historischen Narrativen ist das Argument zugunsten einer “kausalen Plausibilität“ als einem zentralen Kriterium für den Aufbau und die Analyse historischer Narrative unwiderstehlich.

Kontinuität und Wandel sind gleichermaßen grundlegend für die Interpretation von Narrativen. Die chronologische Abfolge von Ereignissen, überzeugende Bestimmungen von Anfängen, Abschlüssen und Perioden, kohärent mit Beurteilungen von Entwicklung, Devolution, Fortschritt und Niedergang: dies sind wesentliche Elemente eines kohärenten Narratives; sie tragen zur Sinnstiftung bei. Diese Dimension könnte “temporale Plausibilität“ genannt werden.

|

Konzept des historischen Denkens (kanadisches Modell) |

Dimension der narrativen Plausibilität |

| Bedeutung | siehe Fußnote[8]. |

| Beleg | auf Beweisen beruhende Plausibilität |

| Kontinuität und Wandel | temporale Plausibilität |

| Ursache und Konsequenz | kausale Plausibilität |

| Perspektive einnehmen | empathische Plausibilität |

| Die ethische Dimension | normative Plausibilität |

Dies besagt nicht, dass das kanadische Modell der Konzepte des historischen Denkens bereits die Probleme der Plausibilität von interpretierenden Narrativen behandelt hat. Stattdessen fügt der Fokus auf den Aufbau und auf die Kritik von Narrativen den Konzepten einen entscheidenden, neuen Aspekt hinzu. Das kanadische Modell hat bislang Diskussionen ausgespart, wie diese Konzepte des historischen Denkens (und eventuell auch das Konzept “Bedeutsamkeit“ [significance]) zum Aufbau und zur Kritik der Interpretationen von Narrativen beitragen können. Die Terminologie Rüsens – die multidimensionalen Kriterien der Plausibilität – bietet einen Ausgangspunkt für ein Verständnis dessen, wie dies funktioniert. Mit der Entwicklung dieser Kriterien auf Englisch werden die GeschichtsdidaktikerInnen und GeschichtslehrerInnen einige leistungsfähige Werkzeuge erhalten, mit denen sie im Klassenzimmer Studierenden und SchülerInnen beibringen können, wie sie narrative Plausibilität beurteilen können.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Penney Clark / Sears Alan: Fiction, History and Pedagogy: A Double-Edged Sword. In: Journal of Curriculum Studies, 5. Oktober 2016, doi: 10.1080/00220272.2016.1238108 .

- Andreas Körber: Translation and Its Discontents II: A German Perspective. In: Journal of Curriculum Studies 48 (2016), H. 4, S. 440-456.

- Peter Seixas / Tom Morton: The Big Six. Historical Thinking Concepts. Toronto 2013.

Webressourcen

- The Historical Thinking Project (Kanada) http://

historicalthinking.ca/ (letzter Zugriff am 6. Dezember 2016). - Jocelyn Létourneau (Quebec, Kanada) https://

jocelynletourneau.com (letzter Zugriff am 6. Dezember 2016).

_____________________

[1] Für die weitere Entwicklung der Ideen in diesem Beitrag siehe: Peter Seixas: Narrative Interpretation in History (and Life). In: Holger Thünemann (Hrsg.): Begriffene Geschichte ‒ Geschichte Begreifen. Essays in Honour of Jörn Rüsen. Frankfurt am Main 2016, und: Peter Seixas: Epilogue: Teaching Rival Histories, in Search of Narrative Plausibility. In: Henrik Åström-Elmersjö / Anna Clark / Robert Parkes (Hrsg.): International Perspectives on Teaching Rival Histories. London (im Erscheinen).

[2] Andreas Körber: Translation and Its Discontents II: A German Perspective. In: Journal of Curriculum Studies 48 (2016), H. 4, S. 440-456, hier S. 449. Die Erklärungen Körbers zu Rüsens Auffassung von Triftigkeit, oder Plausibilität, liefern die Grundlage für diesen Beitrag.

[3] “Not being what it is a picture of is not a defect in pictures, but a necessary condition for something to be a picture at all”, Arthur Danto: Narration and Knowledge (Including the Integral Text of Analytical Philosophy of History). New York 1985, S.114.

[4] Interessanterweise, noch bis 1985, mit der Veröffentlichung von Danto, S. 114ff, existierte einen solchen Konsens offenbar nicht.

[5] Chauncey Monte-Sano: Disciplinary Literacy in History: An Exploration of the Historical Nature of Adolescents’ Writing. In: The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 19 (2010), H. 4, S. 548.

[6] Peter Seixas: A model of historical thinking. In: Educational Philosophy and Theory, 25. Oktober 2015, doi:10.1080/00131857.2015.1101363 (letzter Zugriff am 28. November 2016).

[7] Tyson A. Retz: The History and Function of Empathy in Historical Studies: Re-Enactment and Hermeneutics. University of Melbourne 2016.

[8] Im kanadischen Modell geht es bei dem Begriff “historischen Bedeutung“ (“historical significance”) um die Frage, wie bestimmte Ereignisse oder Personen innerhalb größeren Narrativen passen: sie erreichen Bedeutung durch ihre Rolle in einer größeren Erzählung, die für das heutige Publikum von Bedeutung ist. Wenn “Bedeutung“ als eine Dimension für die Plausibilität von größeren Narrativen eingeführt werden würde, könnte dies zu Verwirrung über die frühere Definition der historischen Bedeutung führen.

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

Historical Thinking Concepts Image © Peter Seixas, 2016.

Übersetzung

Jana Kaiser (kaiser /at/ academic-texts. de)

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Seixas, Peter: Auf der Suche nach narrativer Triftigkeit. In: Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 41, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-7853

Copyright (c) 2016 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 4 (2016) 41

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-7853

Tags: Historical Consciousness (Geschichtsbewußtsein), Narratology (Narrativitätstheorie), Plausibility (Triftigkeit), Theory (Theorie)

Again, very interesting thoughts and a valuable step towards the theoretical junction of two traditions of History Education.

Peter Seixas and Andreas Körber have both already reflected on different meanings of technical terms on historical consciousness in English and German, and I´d like to add a quick remark on the German translation of the text:

It might be misleading to translate the term “narrative” (EN) as “Narrativ” (GER). In common German history education linguistic usage, the term “Narration” (GER) usually refers to a concrete story about the past (e.g. a movie depicting life in the medieval times), whereas “Narrativ” (GER) usually means the abstract meta-narrative, the story behind the story, the interpretative schema/pattern that gives explanations (e.g. the conception that the medieval times where brutal, dark, dirty, misanthropic, barbaric and a cultural setback compared to the ancient times, and that they came into being / to an end because of xyz). Any account on the past–may it include a narrative interpretation or be just a description linking points in time–would be a Narration (GER), while a Narrativ (GER) represents the conceptual notions that derive from these accounts and again manifest themselves in narrations. And it is especially the “Narrativ” (GER) that generates historical meaning.

To my understanding, the English term “narrative” (EN) refers mostly to Narration (GER) in the German sense, while “Narrativ” (GER) would be translated as “master-narrative / grand narrative / meta-narrative” (EN). It could be argued that the Canadian historical thinking concepts offer superb tools to deal especially with meta-narratives, while the problem of Triftigkeit/plausibility applies mostly to concrete narratives. Maybe some clarification on this linguistic issues might be needed.