Abstract: Pedagogías del Sur: Here I present four discussion topics in the field of research in teaching history. These are the hierarchic historiography-teaching relation; the definition of the epistemology of historical knowledge in schools; the centrality of the behaviorist subject; and cognitive imperialism. The aim of discussing these matters is to recover the political dimension in our field of research. My context for discussion is Latin America, but perhaps my reflections can be applied to other latitudes.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-7699.

Languages: Español, English, Deutsch

Pedagogías del Sur: Presento aquí cuatro cuestiones para discutir sobre el campo de la investigación en enseñanza de la historia. Estas son la relación jerárquica historiografía-enseñanza; la definición de la epistemología del conocimiento histórico escolar; la centralidad del sujeto conductista; y el imperialismo cognitivo. Debatir estos asuntos tiene la finalidad de recuperar la dimensión de lo político en nuestro campo de investigación. Mi contexto de discusión es el latinoamericano, pero quizá mis reflexiones puedan extenderse a otras latitudes.[1]

Decontruir el centro

La enseñanza de la historia, en cuanto campo de investigación surgido en Occidente, se estructura a partir de un Centro, Inamovible y Verdadero.[2] El centro es la historiografía, por lo que, de entrada, quienes enseñan o investigan en enseñanza de la historia, se ubican a sí mismos en un lugar marginal, en especial aquellos que estudiaron la carrera de historia. Su función es llevar la ciencia histórica al resto de la población, siempre en un lugar subordinado en relación a la ciencia histórica. Por eso, muchas construcciones didácticas o de investigación, como el pensar históricamente aseveran ser el pensamiento experto o por lo menos emerger del trabajo especializado, pero no son más que creaciones marginales de un centro percibido como inamovible. Pero el problema no sólo es creer que se actúa según el centro o la propia angustia de saberse marginal, sino la necesidad de un centro. En enseñanza de la historia el problema es lo educativo y la lógica rizomática que produce, no la historia y su transposición didáctica.[3]

La investigación para mí, no debe imponer ninguna oposición binaria por las dimensiones políticas que implica su lógica de exclusión. Por eso deberíamos focalizarnos en la dimensión educativa de los usos públicos de la historia, no en el quehacer historiográfico. Quedarse o no en la lógica binaria es una decisión política, no científica. Si nos quedamos decidimos reproducir las viejas exclusiones, si nos movemos aproximamos la investigación a la enseñanza ya que, siguiendo a Freire, si lo relevante es lo educativo de la historia, no podemos eludir su dimensión política.

Epistemología de la historia enseñada

La historia en la escuela es un uso público de la historia. El término público es complejo e imposible abordarlo aquí. En términos llanos, siguiendo la oposición binaria occidental,[4] son todas las formas de producir significados sobre el pasado que no son la historiografía profesional. Por eso, lo importante es que cuando hablamos de la historia en la escuela como un uso público del pasado abandonemos la lógica binaria y tratemos de comprenderla como forma particular de producción de conocimiento histórico.

Es decir, no es la historia profesional convertida en pública, sino que es otra forma de conocimiento histórico, dueño de una función social, unos contenidos, un conjunto de habilidades y una producción situada – la cultura escolar – que la hace distinta a la historiografía. No estoy negando el valor de la historia profesional y sacándola de la escuela, sino que tomo en cuenta que el nacimiento de la historiografía moderna y de los sistemas educativos nacionales en el siglo XIX tuvieron una procedencia semejante, pero la historicidad de cada uno los llevó por caminos muy diferentes.[5] A modo de ejemplo, la pobreza es en determinadas condiciones contenido histórico, pues se imbrica con ladeo historiografía y el conocimiento histórico escolar para producir significados sobre el pasado.

Descentrar al sujeto

La gran mayoría de la didáctica parte de una idea de sujeto universal. Este sujeto es básicamente el esbozado por el conductismo y sus derivaciones cognitivistas, cuyas características pueden ser desglosadas en una serie de operaciones mentales y conductas identificables. Esto implica dos posicionamientos políticos muy importantes.

El primero es que el conductismo armoniza con los indicadores de la racionalidad instrumental de los exámenes masivos, por lo que se convierte en instrumento de evaluación que niega, de facto, la diversidad epistemológica y la variedad de usos de la historia para construir subjetividades. Así, el sujeto universal responde más a las políticas educativas globales que a lo educativo de las historias.

El segundo posicionamiento puede parafrasearse de lo que la teoría decolonial define como modernidad/colonialidad,[6] por lo que el conductismo se basa en la siguiente fórmula; sujeto conductista universal/sujeto cultural local. Por tanto, urge des-psicologizar la enseñanza de la historia y en general la educación,[7] no solo como problema metodológico y didáctico, sino sobre todo como asunto político.

Descentrar los saberes

Hay también que descentrar nuestra práctica de investigación. De nuevo aquí el pensamiento decolonial es muy útil pues nos permite observar el problema en dos dimensiones.

La primera es reconocer cómo de la mano del imperialismo europeo del siglo XIX se renovó la dominación epistemológica. La ciencia fue fundamental en este proceso y dentro de ellas la historia, que vino a América y fue con cinismo a otras partes del mundo a contar la historia de los pueblos que se nombraron pueblos sin historia. Por esto, tenemos que descentrar la geopolítica del conocimiento y establecer un diálogo horizontal que de reconocimiento mutuo. La segunda dimensión es cómo esta ciencia histórica negó otras formas complejas de conocer, narrar e interpretar el pasado.

Para evitarlo hay que valorar desde la diferencia el conocimiento historiográfico y otras formas de pensar y así establecer un diálogo en igualdad de condiciones. Llevarlo a cabo, exige reubicar a la investigación en enseñanza de la historia dentro de las humanidades y no en la ciencia y su lógica de exclusión, pues son la filosofía, la pedagogía, la historia, la literatura, el arte, el psicoanálisis y los saberes culturales diversos, los que nos permitirán pensar nuestro quehacer desde la dimensión teórico y política, y por tanto ética, de la historia pública.[8]

____________________

Bibliografía

- Chatwin, Bruce. Los trazos de la canción. Barcelona 1998.

- Plá, Sebastián / Pagés Joan (Hrsg.): La investigación en enseñanza de la historia en América Latina, México 2014.

- Walsh, Catherine E. / Constanza del Pilar Cuevas Marín: Pedagogías decoloniales: prácticas insurgentes de resistir, (re)existir y (re)vivir. Quito 2013.

Vínculos externos

- Werner Herzog. Where the Green Ants Dream. 1984 www.youtube.com/watch?v=kgmFZ1fUSoY (último acceso 14.11.2016)

- Enrique Escolona. Tlacuilo. 1987 www.youtube.com/watch?v=jB-V_vDReNM (último acceso 14.11.2016)

- Akira Kurosawa. Rashomon. 1950. www.youtube.com/watch?v=t342rqq_dew (último acceso 14.11.2016)

____________________

[1] Presento aquí una síntesis muy apretada de las cuatro cuestiones que guían mis prácticas docente y de investigación. Debo la sistematización de mis ideas a la invitación que me hizo la Asociación de Profesores/as de Enseñanza de la Historia de Universidades Nacionales (APEHUN) para presentarlas en sus XVI Jornadas Nacionales y V Jornadas Internacionales de Enseñanza de la Historia, que se realizaron los días 7, 8 y 9 de septiembre de 2016 en la Facultad de Humanidades de la Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Argentina.

[2] Derrida, Jacques. 1989. “La estructura, el signo y el juego en el discurso de las ciencias humanas”. La escritura y la diferencia. Barcelona: Editorial Anthropos.[3] Esta posición puede considerarse representada por el grupo Nexos, parte importante de la reforma de 1992, aunque su posicionamiento es mucho más complejo que el que expongo aquí. En julio de 2015 publicaron un número de su revista dedicado al tema: http://www.nexos.com.mx/?p=25457 (último acceso 30.4.2016).

[3] Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 2015. “Introducción: rizoma”. Mil mesetas: capitalismo y esquizofrenia. Valencia: Pre-Textos.

[4] Para Ludmila Jordanova, el uso público de la historia es un paraguas general que permite ordenar todas interpretación del pasado que se encuentra por fuera de la historiografía profesional. Jordanova, L. 2000. History in practice. London: Arnold.

[5] Raimundo Cuesta explica cómo la historia escolar y la historiografía profesional tomaron caminos muy distintos en España. Incluso la historia escolar antecedió a la profesionalización de los historiadores (Cuesta, 1997). Esta situación puede extenderse, con sus variaciones, a buena parte de los países latinoamericanos nacidos en el siglo XIX. Cuesta Fernández, Raimundo. 1997. Sociogénesis de una disciplina escolar: la historia. Barcelona: Pomares-Corredor.

[6] “La colonialidad es inmanente a la modernidad, es decir, la colonialidad es articulada como la exterioridad constitutiva de la modernidad. Así, las condiciones de emergencia, existencia y transformación de la modernidad están indisolublemente ligadas a la colonialidad como su exterioridad constitutiva”. Es también “un patrón de poder que opera a través de la naturalización de jerarquías territoriales, raciales, culturales y epistémicas, posibilitando la re-producción de relaciones de dominación” (Restrepo y Rivas, 2010; 16-17). Al llevarlo al sujeto universal, lo que estoy afirmando es que el conductismo sostiene un sujeto universal siempre y cuando exista uno inferior, cultural y local. Restrepo, Eduardo y Axel Rojas. 2010. Inflexión decolonial: fuentes, conceptos y cuestionamientos. [Bogotá]: Instituto de Estudios Sociales y Culturales Pensar, Maestría en Estudios Culturales, Universidad Javeriana.

[7] Cuando hablo de des-psicologizar la educación no me refiero a abandonar los importantes aportes que hace esta disciplina a la educación, sino a su operacionalismo conductista que tiende a reducir el quehacer educativo en una noción de aprendizaje observable y mensurable. Debo esta distinción a los comentarios de Beatriz Aisenberg sobre mi trabajo.

[8] Insisto que hay que buscar un diálogo entre saberes, por eso no hay que renunciar a la sociología, la antropología, la teoría política y la psicología en la enseñanza de la historia, pero hay que verlas y usarlas desde las humanidades.

____________________

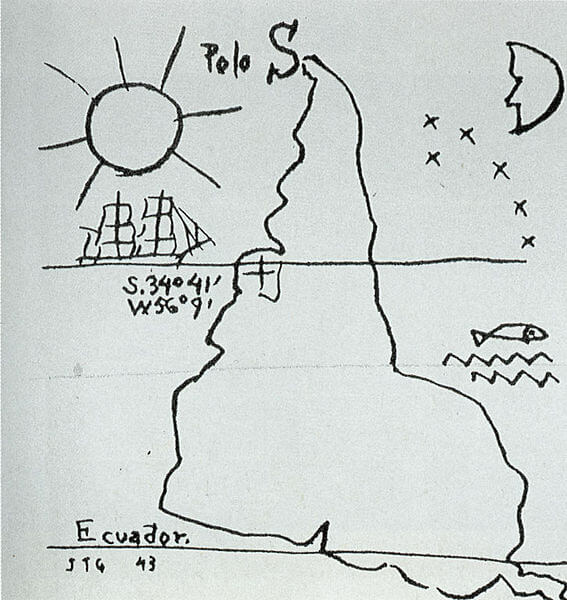

Créditos de imagen

© América invertida, Joaquín Torres García, 1943, wikimedia commons (último acceso 14.11.2016).

Citar como

Plà, Sebastiàn: Pedagogías del Sur: Repensar la investigación. In: Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 38, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-7699.

Pedagogías del Sur: Here I present four discussion topics in the field of research in teaching history. These are the hierarchic historiography-teaching relation; the definition of the epistemology of historical knowledge in schools; the centrality of the behaviorist subject; and cognitive imperialism. The aim of discussing these matters is to recover the political dimension in our field of research. My context for discussion is Latin America, but perhaps my reflections can be applied to other latitudes.[1]

Deconstructing The Center

The teaching of history, in any field of research in the West, is structured on the basis of a fixed, true Center.[2] The center is historiography, so from the start, those who teach or do research in the teaching of history position themselves in a marginal location, especially those who were trained in the field of history. Its function is to take historical science to the rest of the population, always in a subordinate position with regard to historical science. Consequently, many didactic and research constructions, such as thinking historically, claim to be expert thought or at least to emerge from specialized work, but they are not more than marginal creations to a center perceived as fixed. However, the problem is not only to believe that one acts in reference to the center or the very distress of knowing one is marginal, but rather the need for a center. In teaching history the problem is the educational dimension and the rhizomatic logic that is produced, not history and its didactic transposition.[3]

For me research should not impose a binary opposition for political dimensions that imply their logic of exclusion. Therefore, we must focus on the educational dimension of public uses of history, not on the historiographical task. Adhering to binary logic or not is a political decision, not a scientific one. If we stay we decide to reproduce the traditional exclusions, if we move we approach enquiry into teaching, because, following Freire, if what is relevant is the educational dimension of history, we cannot elude its political dimension.

Epistemology Of Taught History

History in school is a public use of history. The term “public” is complex and impossible to address here. In simple terms, following Western binary opposition,[4] it implies all forms of producing meaning about the past that are not professional historiography. As a result, what is important when we speak of history in school as a public use of the past, we abandon binary logic and we attempt to understand it as a particular way of producing historical knowledge.

In other words, it is not professional history converted into public history, but rather another form of historical knowledge, owner of a social function, some content, a body of skills and production in a context-school culture that makes it unlike historiography. I am not denying the value of professional history and removing it from school, instead I take into account the fact that the birth of modern historiography and national educational systems in the nineteenth century had a similar provenance, but the historicity of each took highly different turns.[5] For example, poverty is historical content in certain circumstances, for it is imbricated with historiography and historical knowledge in school to produce meanings about the past.

Decentering The Subject

The vast majority of teaching starts from an idea of universal subject. This subject is basically what is outlined by behaviorism and its cognitivist derivations, whose characteristics can be broken down into a series of identifiable mental and behavioral operations. This implies two important political stances.

The first is that behaviorism is in harmony with the indicators of the instrumental rationality of massive exams, so it becomes an instrument of evaluation that denies, de facto, epistemological diversity and the variety of uses of history to construct subjectivities. Thus, the universal subject responds more to global educational policies than to educational aspects of histories.

The second position can be paraphrased from what decolonial theory defines as modernity/coloniality,[6] so behaviorism is based on the following formula: universal behaviorist subject/local cultural subject. Therefore, it is urgent to de-psychologize the teaching of history and education in general,[7] not only as a methodological and didactic problem, but above all as a political matter.

Decentralizing Knowledge

Our research practice must also be decentralized. Again, here decolonial thought is highly useful, for it enables us to observe the problem in two dimensions. The first is to recognize how the hand of nineteenth-century European imperialism renewed epistemological domination. Science was fundamental in this process and within it, history, which came to America and went with cynicism to other parts of the world to tell the history of peoples who were named peoples without history. Therefore, we have to decentralize the geopolitics of knowledge and to establish a horizontal dialogue that provides mutual recognition. The second dimension is how this historical science denied other complex forms of knowing, narrating, and interpreting the past.

To avoid this, it is necessary to evaluate the subject from the perspective of the difference of historiographic knowledge and other ways of thinking to establish a dialogue in equal conditions. To carry this out requires repositioning research in teaching history within the humanities and not in science and its logic of exclusion, for it is philosophy, pedagogy, history, literature, art, psychoanalysis, and diverse cultural forms of knowledge that will enable us to think of our task from the theoretical and political, and thus ethical dimension of public history.[8]

_____________________

Further Reading

- Chatwin, Bruce. Los trazos de la canción. Barcelona: Muchnik, 1998.

- Plá, Sebastián and Pagés Joan (coord.). La investigación en enseñanza de la historia en América Latina, Mexico City: Universidad Pedagógica Nacional-Bonilla Artigas, 2014.

- Walsh, Catherine E., and Constanza del Pilar Cuevas Marín. Pedagogías decoloniales: prácticas insurgentes de resistir, (re)existir y (re)vivir. Quito: Abya-Yala, 2013.

Web Resources

- Werner Herzog. Where the Green Ants Dream. 1984 www.youtube.com/watch?v=kgmFZ1fUSoY (last accessed 14 November 2016)

- Enrique Escolona. Tlacuilo. 1987 www.youtube.com/watch?v=jB-V_vDReNM (last accessed 14 November 2016)

- Akira Kurosawa. Rashomon. 1950. www.youtube.com/watch?v=t342rqq_dew (last accessed 14 November 2016)

_____________________

[1] Here I present a brief synthesis of the four questions that guide my teaching and research practice. I owe the systematization of my ideas to the invitation I received from the Asociación de Profesores/as de Enseñanza de la Historia de Universidades Nacionales (APEHUN) to present them at their XVI Jornadas Nacionales and V Jornadas Internacionales de Enseñanza de la Historia, which were held on September 7, 8 and 9, 2016 in the Facultad de Humanidades of the Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Argentina.

[2] Derrida, Jacques. “La estructura, el signo y el juego en el discurso de las ciencias humanas.” La escritura y la diferencia. Barcelona: Editorial Anthropos, 1989.

[3] Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. “Introducción: rizoma.” Mil mesetas: capitalismo y esquizofrenia. Valencia: Pre-Textos, 2015.

[4] For Ludmila Jordanova, the public use of history is a general umbrella term that makes it possible to order all interpretations of the past that are not part of professional historiography. Jordanova, Ludmila. History in practice. London: Arnold, 2000.

[5] Raimundo Cuesta explains how history in school and professional historiography took highly different paths in Spain. In fact, school history preceded the professionalization of historians (Cuesta, 1997). This situation can be applied, with variations, to many Latin American countries born in the nineteenth century. Cuesta Fernández, Raimundo. Sociogénesis de una disciplina escolar: la historia. Barcelona: Pomares-Corredor, 1997.

[6] “Coloniality is immanent to modernity, that is to say, coloniality is articulated as the exteriority constituent of modernity. Thus, the conditions of the emergence, existence, and transformation of modernity are indissolubly linked to coloniality as its constituent exteriority.” It is also “a pattern of power that operates through the naturalization of territorial, racial, cultural, and epistemic hierarchies, permitting the re-production of relations of domination” (Restrepo and Rivas, 2010; 16–17). By employing the universal subject, what I am claiming is that behaviorism supports a universal subject as long as a local, cultural inferior exists. Restrepo, Eduardo and Axel Rojas. Inflexión decolonial: fuentes, conceptos y cuestionamientos. [Bogotá]: Instituto de Estudios Sociales y Culturales Pensar, Maestría en Estudios Culturales, Universidad Javeriana, 2010.

[7] When I speak of de-psychologizing education, I am not referring to abandoning the important contributions this discipline makes to education; instead I mean its behaviorist operationalism that tends to reduce the task of education to a notion of observable and measurable learning. I owe this distinction to the comments of Beatriz Aisenberg on my work.

[8] I insist that it is necessary to seek dialogue between these fields of knowledge, so it is not necessary to renounce sociology, anthropology, political theory, and psychology in the teaching of history, but it is necessary to see them and use them from the perspective of the humanities.

_____________________

Image Credits

© América invertida, Joaquín Torres García, 1943, wikimedia commons (last accessed 14 November 2016).

Recommended Citation

Plá, Sebastián: Pedagogías del Sur: Rethinking Research. In: Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 38, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-7699.

Pedagogías del Sur: Ich präsentiere hier vier Fragen zur Diskussion der Geschichtsunterrichts-Forschung: Das sind die hierarchische Beziehung zwischen Geschichtsschreibung und Unterricht, die Festlegung der Epistemologie des schulischen Geschichtswissens, die zentrale Bedeutung der behavioristischen Thematik und der kognitive Imperialismus. Ziel der Debatte ist es, die politische Dimension in unserer Forschung wiederzuerlangen. Den Kontext meiner Fragen bildet Lateinamerika, aber meine Überlegungen treffen möglicherweise auch auf andere Breitengrade zu.[1]

Das Zentrum dekonstruieren

Der Geschichtsunterricht ist, auf jedem Forschungsgebiet im Westen, auf der Basis eines festgelegten wahren Zentrums strukturiert.[2] Dieses Zentrum ist die Geschichtsschreibung. Von Anfang an positionieren sich deshalb diejenigen, die Geschichtsdidaktik lehren oder Geschichtsunterricht erforschen, an einem marginalen Ort, vor allem diejenigen, die auf dem Fachgebiet der Geschichte ausgebildet wurden. Ihre Funktion besteht darin, die Geschichtswissenschaft dem Rest der Bevölkerung näherzubringen, immer in einer untergeordneten Stellung gegenüber der Geschichtswissenschaft. Demzufolge beanspruchen viele Didaktik- und Forschungskonstruktionen, wie zum Beispiel die des Historischen Denkens, historische Expertise für sich oder geben zumindest vor, Fachstudien zu entstammen. Sie sind jedoch nicht mehr als auf einem fixiert wahrgenommenen Zentrum beruhende, marginale Schöpfungen. Das Problem ist indes nicht nur zu glauben, dass man in Bezug auf das Zentrum handelt, oder die absolute Verzweiflung, dass man um seine Marginalität weiß, sondern vielmehr das Bedürfnis nach einem Zentrum. Das Problem im Geschichtsunterricht ist die pädagogische Dimension und die rhizomatische Logik, die produziert wird, als Problem – nicht Geschichte an sich und ihre didaktische Umsetzung.[3]

Meines Erachtens sollte die Forschung nicht eine binäre Entgegensetzung für politische Dimensionen einführen, die ihre Logik der Ausschlusses impliziert. Deshalb müssen wir uns auf die pädagogische Dimension des öffentlichen Gebrauchs von Geschichte fokussieren, nicht auf die historiographische Aufgabe. An der binären Logik festzuhalten oder nicht, das ist eine politische Entscheidung, nicht eine wissenschaftliche. Wenn wir dabei bleiben, entschliessen wir uns, die traditionellen Ausschlüsse zu reproduzieren; wenn wir uns hingegen bewegen, kommen wir der Erforschung von Unterricht näher, weil, wenn die pädagogische Dimension die relevante ist, wir, gemäss Freire, der politischen Dimension nicht ausweichen können.

Die Epistemologie der unterrichteten Geschichte

Geschichte in der Schule ist öffentlicher Gebrauch von Geschichte. Der Begriff “öffentlich” ist komplex, und es ist nicht möglich, sich mit ihm an dieser Stelle zu befassen. Einfach gesagt, gemäss der nachfolgenden westlichen binären Entgegensetzung,[4] impliziert er alle Arten von Sinngebung in Bezug auf die Vergangenheit, die nicht professionelle Historiographie ist. Infolgedessen ist es wichtig, dass, wenn wir in der Schule von Geschichte als öffentlichem Gebrauch der Vergangenheit sprechen, wir die binäre Logik beiseite lassen und versuchen, dies als eine spezielle Art, wie historisches Wissen produziert wird, zu verstehen.

In anderen Worten, es handelt sich nicht um professionelle Geschichte, die in Public History umgewandelt wird, sondern eher um eine andere Form von historischem Wissen, Eigentümer einer sozialen Funktion, Inhalt, ein Gefäss von Fähigkeiten und Produktion in einer kontext-schulischen Kultur, die anders vorgeht als Geschichtsschreibung. Ich bestreite weder den Wert der professionellen Geschichte, noch verbanne ich sie aus der Schule, stattdessen nehme ich die Tatsache in Betracht, dass die Geburt der modernen Geschichtsschreibung und die nationalen Schulsysteme im 19. Jahrhundert denselben Ursprung hatten, dann aber eines jeden Entwicklung ganz andere Wege einschlug.[5] Armut zum Beispiel wird unter ganz bestimmten Bedingungen zu einem historischen Inhalt, denn hier sind Geschichtsschreibung und Schulgeschichtswissen verzahnt, um Sinn über Vergangenheit herzustellen.

Das Subjekt dezentrieren

Der Großteil von Unterricht geht von der Idee des universellen Subjekts aus. Dieses Subjekt ist im Wesentlichen, was durch den Behaviorismus und seine kognitiven Ableitungen umrissen wird, dessen Charakteristika in eine Reihe von identifizierbaren Mental- und Verhaltensabläufen unterteilt werden kann. Dies impliziert zwei wichtige politische Haltungen.

Die erste beinhaltet, dass der Behaviorismus in Einklang mit den Indikatoren der instrumentellen Vernunft ausgedehnter Prüfungen steht; dadurch wird er zu einem Evaluationsinstrument, der de facto die epistemologische Diversität und die Varietät von Geschichtsanwendungen zum Zwecke der Subjektivitätskonstruktion verleugnet. Das universelle Subjekt stimmt so mehr mit globaler Bildungspolitik überein als mit den pädagogischen Aspekten von Geschichten.

Die zweite Haltung kann aus dem, was die Dekonialitäts-Theorie [Deconiality] als Modernität/Kolonialiät definiert, umschrieben werden;[6] demzufolge basiert Behaviorismus auf der folgenden Formel: universelles behavioristisches Subjekt/lokal-kulturelles Subjekt. Deshalb muss der Geschichtsunterricht und die Bildung im Allgemeinen dringend ent-psychologisiert werden,[7] nicht nur im Sinne eines methodischen und didaktischen Problems, sondern vor allen Dingen als politisches Anliegen.

Wissen dezentralisieren

Unsere Wissenschaftspraxis muss also dezentralisiert werden. Hier ist wiederum ‘dekoloniales’ Denken äußerst nützlich, denn es erlaubt uns, das Problem hinsichtlich zweier Dimensionen zu betrachten. Die erste besteht darin, zu erkennen, wie der europäischen Imperialismus des 19. Jahrhunderts seine epistemologische Vorherrschaft erneuerte. Die Wissenschaft, und mit ihr die Geschichte, spielte eine fundamentale Rolle in diesem Prozess, sie gelangte nach Amerika und mit Zynismus weiter in andere Teile der Welt, um die Geschichte von Völkern, die Völker ohne Namen genannt wurden, zu erzählen. Deshalb müssen wir die Geopolitik des Wissens dezentralisieren und einen Dialog auf Augenhöhe schaffen, der gegenseitige Anerkennung bringt. Die zweite Dimension stellt dar, wie die Geschichtswissenschaft andere komplexe Formen des Wissens, des Erzählens und des Interpretierens der Vergangenheit ablehnte.

Um dies zu vermeiden, ist es notwendig, das Subjekt von der Perspektive des Unterschieds zwischen historiographischem Wissen und anderen Arten des Denkens zu evaluieren, um einen Dialog mit gleichen Bedingungen zu schaffen. Um dies zu bewerkstelligen, ist es erforderlich, die Forschung in Bezug auf Geschichtsunterricht innerhalb der Geisteswissenschaften neu zu positionieren, aber nicht in der Wissenschaft und seiner Logik der Ausschliessung, denn es sind die Philosophie, Pädagogik, Geschichte, Literatur, Kunst, Psychoanalyse und verschiedene Kulturformen des Wissens, die es uns ermöglichen, unsere Aufgabe aus der theoretischen und politischen und folglich aus der ethischen Dimension der Public History zu verstehen.[8]

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Chatwin, Bruce. Los trazos de la canción. Barcelona 1998.

- Plá, Sebastián / Pagés Joan (Hrsg.). La investigación en enseñanza de la historia en América Latina, Mexico City 2014.

- Walsh, Catherine E. / Constanza del Pilar Cuevas Marín: Pedagogías decoloniales: prácticas insurgentes de resistir, (re)existir y (re)vivir. Quito 2013.

Webressourcen

- Werner Herzog. Where the Green Ants Dream. 1984 www.youtube.com/watch?v=kgmFZ1fUSoY (letzter Zugriff am 14.11.2016)

- Enrique Escolona. Tlacuilo. 1987 www.youtube.com/watch?v=jB-V_vDReNM (letzter Zugriff am 14.11.2016)

- Akira Kurosawa. Rashomon. 1950. www.youtube.com/watch?v=t342rqq_dew (letzter Zugriff am 14.11.2016)

_____________________

[1] Hier präsentiere ich eine kurze Zusammenfassung der vier Fragen, die meinen Unterricht und meine Forschungspraxis leiten. Ich schulde die Systematisierung meiner Ideen der Einladung, die ich von der Asociación de Profesores/as de Enseñanza de la Historia de Universidades Nacionales (APEHUN) erhalten habe, um diese an ihrem XVI Jornadas Nacionales und V Jornadas Internacionales de Enseñanza de la Historia vorzustellen, welche am 7., 8. und 9. September 2016 an der Facultad de Humanidades of the Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Argentina stattfand.

[2] Derrida, Jacques: La estructura, el signo y el juego en el discurso de las ciencias humanas. La escritura y la diferencia. Barcelona 1989.

[3] Deleuze, Gilles / Félix Guattari. Introducción: rizoma. Mil mesetas: capitalismo y esquizofrenia. Valencia 2015.

[4] Für Ludmila Jordanova ist “öffentlicher Gebrauch von Geschichte” eine allgemeine Chiffre, welche erlaubt, alle Interpretationen der Vergangenheit, die nicht zur professionellen Historiographie gehören, zu ordnen.

[5] Raimundo Cuesta erläutert, wie die Geschichte in der Schule und die professionelle Historiographie in Spanien sehr unterschiedliche Wege nahmen. Die schulische Geschichte ging der Professionalisierung durch die Historiker effektiv voraus (Cuesta, 1997). Diese Situation trifft mit Abweichungen auf viele lateinamerikanische Länder zu, die im neunzehnten Jahrhundert entstanden. Cuesta Fernández, Raimundo: Sociogénesis de una disciplina escolar: la historia. Barcelona 1997.

[6] “Kolonialität ist der Modernität immanent, genauer gesagt, Kolonialität artikuliert sich als äussere Komponente von Modernität. Somit sind die Bedingungen des Entstehens, der Existenz und der Transformation von Modernität untrennbar verknüpft mit Kolonialität als ihre äussere Komponente.“ Sie ist auch “eine Machtstruktur, welche durch die Naturalisation von territorialen, rassischen, kulturellen und epistemischen Hierarchien bewirkt wird, welche die Reproduktion von Beziehungen der Vorherrschaft erlaubt“ (Restrepo and Rivas, 2010; 16–17).

[7] Wenn ich davon spreche, die Bildung zu ent-psychologisieren, meine ich damit nicht, die wichtigen Beiträge, die diese Disziplin in Bezug auf die Bildung leistet, aufzugeben; stattdessen beziehe ich mich auf ihren behavioristischen Operationalismus, welcher dazu tendiert, die Bildungsaufgabe auf eine Idee des beobachtbaren und messbaren Lernens zu reduzieren. Diese Unterscheidung schulde ich den Bemerkungen von Beatriz Aisenberg zu meiner Arbeit.

[8] Ich lege grossen Wert darauf zu betonen, dass es wichtig ist, den Dialog zwischen diesen Bereichen des Wissens zu suchen; infolgedessen ist es nicht geboten, im Geschichtsunterricht auf die Soziologie, Anthropologie, politische Theorie und Psychologie zu verzichten, sondern es ist unerlässlich diese zu verstehen und von der Perspektive der Geisteswissenschaften anzuwenden.

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

© América invertida, Joaquín Torres García, 1943, wikimedia commons (letzter Zugriff am 14.11.2016)

Übersetzung

Kurt Brügger swiss american language expert

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Plá , Sebastián: Pedagogías del Sur: Forschung überdenken. In: Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 38, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-7699.

Copyright (c) 2016 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 4 (2016) 38

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-7699

Tags: Colonial Legacy (Koloniales Erbe), History Didactics (Geschichtsdidaktik), History Teaching (Geschichtsunterricht), Language: Spanish, Postcolonial Perspectives, Theory (Theorie)