Abstract:

All history is narrative to one degree or another, as Danto has shown, and those who disdain narrative usually end-up telling stories, nonetheless, in their historical writing. We all live narrative projects, in one sense or another, tacitly or explicitly. Narratives entail ethics, in so far as they orient action towards self and other and characterise the agents they narrate by attributing value status to them.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-7659.

Languages: English, Deutsch

All history is narrative to one degree or another, as Danto has shown,[1] and those who disdain narrative usually end-up telling stories, nonetheless, in their historical writing.[2] We all live narrative projects, in one sense or another, tacitly or explicitly.[3] Narratives entail ethics, in so far as they orient action towards self and other and characterise the agents they narrate by attributing value status to them.

Narratives as Projects and Projections

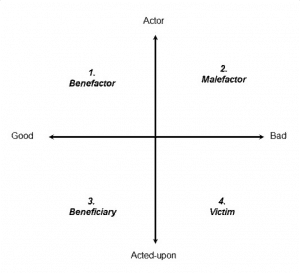

In Hope and Memory and elsewhere, Tzvetan Todorov explores narratives as projects and projections, and as alibis and excuses, and itemises various narrative vices, including Manicheanism. The following schema (Figure 1), based on Chapter 3 of Hope and Memory, models some forms of moral self-characterisation in narrative.

Figure 1. Todorov’s moral typology of narrative agency © Arthur Chapman

The figure models four ideal types. In the first type (‘Benefactor’), a narrator represents themselves, or the group with whom they identify, as a ‘doer of good’ and in the second type (‘Malefactor’), as the ‘doer of ill’. In the third (‘Beneficiary’) they are the recipient of good and in the fourth (victim) of bad from others. Some positions in the schema “can be filled to personal advantage (the beneficent hero, the innocent victim), and two bring no advantage (the malefactor and the passive beneficiary)”.[4] Few wish to be seen as the ‘doer-of-evil’ but it is pleasing to be a ‘doer-of-good’. To be a ‘beneficiary’ is to be dependent on others, which puts those who ‘do the good’, on the moral high ground. Adopting the ‘victim’ position is an acknowledgement of weakness but it, nevertheless, connotes superiority, since a victim has a moral claim on those who have done them harm.

All four ideal types are ‘Manichean’ and in at least three senses: through a binarism, first, of qualities (‘good’ / ‘evil’), second, of roles (‘actors’ / ‘acted-upon’) and, third, of entities (‘we’ / ‘they’). Although there are times when the world is best described in Manichean terms, ethical realism usually paints the world chiaroscuro and in polychrome. We tend, nevertheless, particularly when young, to prefer binaries, “clarity” and “the sharp cut”.[5]

What relevance does all of this have for public history and history education?

Identify and Diagnose Historical Vices

First, perhaps, this schema can be used to identify and diagnose historical vices and to put historical culture to the test. Recent debates and policy on national identity in the UK, for example, have displayed many Manichean features that are ripe for deconstruction. UK Government documents have moved to minimise the representation of ‘problematic’ aspects of our past,[6] English government ministers have sought to demonize those who have sought to address these issues through education as enemies-within “trashing… our past” [7] and the former Director of our British Museum has described British public culture as ‘dangerous’ because focused only on the ‘good’ that ‘we’ have done.[8] On the other hand, perhaps we can see a mirror-image Manicheanism in the claims of the unmaskers of the stain of Empire (and cognate ‘sins of the fathers’) who tend to find nothing but bad and deliberate distortion at the root of national institutions. [9]

Antidotes to National Narcissisms

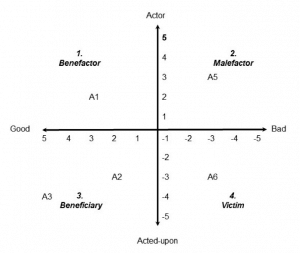

Second, the schema can be used to provide antidotes to national narcissisms, in positive and negative variants. Todorov’ recommends narrating one’s history from the ‘inglorious’ positions in the table as a corrective heuristic – for example, setting out to narrate one’s nation from a ‘beneficiary’ position, in which the contributions of ‘others’ are foregrounded. Perhaps the key move to make, however, is one that enables an alternative approach and that avoids the binarism that Todorov’s model both instantiates and criticises. Manicheanism and binary oppositions can, perhaps, be obviated by the introduction of analogue scales that one can move up and down by degrees when appraising aspects of the past (Figure 2). One might ask, then, to what degree ‘one’s group’ was agent and / or acted-upon in a particular historical context and to what degree it perpetrated and / or benefitted from ‘good’ or ‘ill’. One could perhaps go further and begin to break down the opposition between one positive vale and one negative value on each dimension by mapping multiple aspects (A1 to A6 in Figure 2, below) of one’s groups’ role in the same past event onto the figure – considering what was and was not done and / or experienced by various component elements of one’s ‘group’, in military terms, economic terms, and so on.

Figure 2. A modified ‘analogue’ version of Todorov’s typology, mapping different aspects (A1-A6) of the same agent’s role in a hypothetical event © Arthur Chapman

Deconstruct the Binarism of Identity

Third, the modified model (Figure 2) helps to foreground and thus, perhaps, deconstruct, the binarism of identity and open it up to differentiation, as Michael Mann has done by demonstrating the ways in which the unitary term ‘society’ masks plural identities created by social agents’ simultaneous participation in multiple, overlapping and often somewhat contradictory networks of interaction.[10] Once multiple dimensions of collective agency are acknowledged one can begin to ask in what sense we can talk of a singular agent in relation ‘nations’. One can also, perhaps, begin to deconstruct the simplistic and ahistorical identification between ‘us back then’ and ‘us now’ by showing how, now as then, ‘we’ contains ‘multitudes’ and multiple and often contradictory qualities.[11]

Finally, by focusing on how narratives construct moral meaning – even when they do not aim primarily to ‘sit in judgment’ – Todorov’s typology can, perhaps, help to foreground a relatively neglected yet unavoidable aspect of historical narration: the ethical dimension that no attempt to consider human action and inaction can avoid.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Levi, P. (1988). The Drowned and The Saved, London: Abacus.

- Todorov, T. (2014). The Inner Enemies of Democracy. Cambridge: Polity.

Web Resources

- The Guardian: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/mar/11/battle-britain-history-new-uk-citizens (last accessed 06. November 2016).

- politics.co.uk: http://www.politics.co.uk/news/2010/10/5/gove-schools-will-stop-trashing-our-past (last accessed 06. November 2016).

_____________________

[1] Danto, A. (2007) Narration and Knowledge. New York: Columbia University Press

[2] Megill, A. (1989) ‘Recounting the Past: “Description,” Explanation, and Narrative in Historiography’. The American Historical Review, 94 (3), pp. 627-653.

[3] Carr, D. (2014) Experience and History: Phenomenological perspectives on the historicized world. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[4] Todorov, T. (2003) Hope and Memory: Reflections on the 20th Century. London: Atlantic Books, p.144.

[5] Levi, P. (1988) The Drowned and The Saved, London: Abacus, p.23.

[6] Edgar, D. (2013, March 11). The British history new citizens must learn: no radicals, no homosexuals, no Holocaust. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/mar/11/battle-britain-history-new-uk-citizens (last accessed 06. November 2016).

[7] Wozniak, P. (2010) Gove: Schools will ‘stop trashing our past’. Politics.Co.UK, 5 October 2010. Retrieved from http://www.politics.co.uk/news/2010/10/5/gove-schools-will-stop-trashing-our-past (last accessed 06. November 2016).

[8] Connolly, K. (2016) Neil MacGregor: ‘Britain forgets its past. Germany confronts it’. The Guardian, 7 October 2016. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2016/oct/07/britains-view-of-its-history-dangerous-says-former-museum-director (last accessed 06. November 2016).

[9] O’Neill, B. (2015) Never mind Rhodes – it’s the cult of the victim that must fall. Spiked, 28 December 2015. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2016/oct/07/britains-view-of-its-history-dangerous-says-former-museum-director (last accessed 06. November 2016).

[10] Mann, M. (2012) The Sources of Social Power, Volumes I-IV. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[11] Whitman, W. (1990) The Leaves of Grass. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p.78.

_____________________

Image Credits

© Arthur Chapman

Recommended Citation

Chapman, Arthur: On the diagnosis and treatment of narrative vices. In: Public History Weekly 4 (2016) 37, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-7659

Wie Danto aufgezeigt hat, ist Geschichte als solche mehr oder weniger narrativ,[1] und diejenigen, die das Narrative ablehnen, kommen in ihrer Geschichtsschreibung schließlich gleichwohl ins Geschichten erzählen.[2] Wir alle sind in unserem Leben, auf die eine oder andere Art, in narrative Projekte verwickelt, sei es implizit oder explizit.[3] Narrative beinhalten Ethik, insoweit, als dass sie Handlung auf das Selbst und das Andere beziehen und Handelnde, über die sie berichten, charakterisieren, indem ihnen Statuswert zugeschrieben wird.

Narrative als Projekte und Projektionen

In Hope and Memory und an anderer Stelle betrachtet Tzvetan Todorov in seiner Forschung Narrative als Projekte und Projektionen ebenso wie als Alibis und Ausreden und listet verschiedene narrative Untugenden auf, unter anderem Manichäismus. Das folgende Schema (Abbildung 1) zeigt einige Formen von moralischer Selbstcharakterisierung im Narrativen auf.

Abbildung 1: Todorov’s moral typology of narrative agency © Arthur Chapman

Die Darstellung bildet vier Idealtypen ab. Im ersten Typus (‘Wohltäter’) stellt sich der Erzähler selbst oder die Gruppe, mit welcher er sich identifiziert, als “jemanden, der Gutes tut” dar und im zweiten Typus als “jemanden, der Schlechtes tut”. Im dritten (‘Nutzniesser’) ist er der Empfänger von Gutem und im vierten (Opfer) von Schlechtem seitens anderer. Einige Positionen im Schema „können dem Bereich des persönlichen Vorteils zugeordnet werden (der wohltätige Held, das unschuldige Opfer) und zwei weitere bringen keinen Vorteil (der Übeltäter und der passive Nutzniesser)“.[4] Nur wenige wünschen als ‘Übeltäter’ angesehen zu werden, wohingegen es erfreulich ist, ein ‘Wohltäter’ zu sein. ‘Nutzniesser’ zu sein, bedeutet, von anderen abhängig zu sein, was diejenigen, die “das Gute begehen” auf ein moralisches Podest stellt. Die Position des ‘Opfers’ zu übernehmen, bedeutet das Eingestehen von Schwäche, aber impliziert dennoch auch die Konnotation von Überlegenheit dadurch, dass das Opfer einen moralischen Anspruch an diejenigen hat, die ihm Schaden zugefügt haben.

Alle vier Idealtypen sind ‘manichäisch’ und dies in zumindest drei Hinsichten: bedingt durch einen Binärismus, erstens, der Eigenschaften (‘gut’ / ‘böse’), zweitens, der Rollen (‘Handelnder’ / ‘angetan-werdend’) und, drittens, der Personen (‘wir’ / ‘sie’). Wir haben allerdings die Tendenz, vor allem im Jugendalter, Binariäten zu bevorzugen, “Klarheit” und “das Scharfgeschnittene”.[5]

Welche Relevanz hat all dies in Bezug auf Public History und historische Bildung?

Das Erkennen und Diagnostizieren von geschichtlichen Untugenden

Dieses Schema kann vielleicht zuerst einmal dazu benutzt werden, geschichtliche Untugenden zu erkennen und zu diagnostizieren sowie die Geschichtskultur zu erproben. In Großbritannien haben jüngste Debatten und die Politik in Bezug auf die nationale Identität zum Beispiel manichäische Züge zum Vorschein gebracht, die reif sind für Dekonstruktion. Regierungsdokumente haben angesetzt, die Darstellung von ‘problematischen’ Aspekten aus unserer Vergangenheit zu minimieren,[6] Regierungsminister haben versucht, diejenigen zu dämonisieren, die bestrebt waren, diese Themen im Unterricht anzusprechen, nämlich als innere Feinde, welche “unsere Vergangenheit… zu Müll machen,”[7] und der ehemalige Direktor unseres Britischen Museums hat unsere öffentliche Kultur als “gefährlich” bezeichnet, weil sie nur auf das ‘Gute’, das ‘wir’ getan haben, fokussiert.[8] Andererseits erkennt man vielleicht ein Spiegelbild-Manichäismus in den Behauptungen der Kritiker der Makel des Empires (und verwandte “Sünden der Väter”), welche dazu tendieren, nichts als schlechte und bewusste Verfälschung an der Wurzel von nationalen Institutionen aufzufinden.[9]

Gegenmittel für nationalen Narzissmus

Das Schema kann zweitens als Gegenmittel für nationalen Narzissmus dienen, in der Form von positiven und negativen Ausprägungen. In seiner Aufstellung schlägt Todorov vor, die eigene Geschichte von “unrühmlichen” Perspektiven aus zu erzählen, und sieht dies als korrektive Heuristik an – zum Beispiel anzusetzen, die eigene Nation von der Position eines “Begünstigten” aus zu beschreiben, innerhalb welcher, die Leistungen “anderer” in den Vordergrund gerückt werden. Die Schlüsselvorgehensweise dazu ist indes vielleicht eine, die einen alternativen Ansatz ermöglicht und die den Binärismus verhindert, den Todorovs Modell sowohl impliziert als auch kritisiert. Manichäismus und binäre Gegensätze können vielleicht verhindert werden durch das Einführen von analogen Skalen, auf denen man sich beim Bewerten von Aspekten aus der Vergangenheit (Abbildung 2) graduell hinauf und hinunter bewegen kann. Man kann sich dann fragen, in welchem Ausmaß die ‘eigene Gruppe’ als Handelnder und / oder Leidender in einem speziellen historischen Kontext auftrat und in welchem Ausmaß diese Gruppe ‘Gutes oder Böses’ verübte und / oder davon begünstigt wurde. Man könnte vielleicht weitergehen und anfangen, den Gegensatz zwischen einem positiven Wert und einem negativen Wert innerhalb jeder Dimension aufzulösen, indem man die mehrfachen Aspekte (A1 bis A6 in Abbildung 2, unten), die die Rolle der eigenen Gruppe bezüglich desselben Ereignisses aus der Vergangenheit beinhaltet, auf der Abbildung differenziert darstellt – dabei in Betracht ziehend, was getan oder nicht getan und / erlebt wurde durch verschiedene Elemente der eigenen Gruppe, militärisch, wirtschaftlich und so weiter.

Figure 2. A modified ‘analogue’ version of Todorov’s typology, mapping different aspects (A1-A6) of the same agent’s role in a hypothetical event © Arthur Chapman

Binarität der Identität dekonstruieren

Das modifizierte Model (Abbildung 2) dient drittens dazu, die Binarität der Identität in den Vordergrund zu rücken und dadurch vielleicht Zugang für eine Differenzierung zu ermöglichen, wie Michael Mann dies getan hat, indem er die Varianten demonstriert hat, in denen der Einheitsbegriff ‘Gesellschaft’ Mehrfach-Identitäten maskiert, bewirkt durch das gleichzeitige Teilhaben sozial Handelnder in multiplen, sich überlappenden und oft widersprüchlichen Netzwerken der Interaktion.[10] Wenn multiple Dimensionen von kollektiver Handlung erst einmal anerkannt werden, kann man sich zu fragen anfangen, inwiefern wir von einem einzelnen Handelnden in Bezug auf ‘Nationen’ sprechen können. Man kann vielleicht auch damit beginnen, simplifizierende und ahistorische Identifikation zwischen ‘uns von damals’ und ‘uns von heute’ zu dekonstruieren, indem man aufzeigt, wie das ‘Wir’ sowohl heute wie damals eine ‘Vielzahl’ von ebenso multiplen wie widersprüchlichen Eigenschaften beinhaltet.[11]

Und schließlich, durch das Fokussieren darauf, wie Narrative moralische Bedeutung konstruieren – selbst wenn diese nicht hauptsächlich darauf abzielen, “zu Gericht zu sitzen” -, erlaubt Todorovs Typologie vielleicht, einen relativ vernachlässigten und dennoch unvermeidbaren Aspekt der historischen Narration in den Vordergrund zu rücken: die ethische Dimension, die keinen Versuch vermeiden kann, stattfindende wie nicht-stattfindende menschliche Handlungen einer genauen Betrachtung zu unterziehen.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Levi, Primo: The Drowned and The Saved. London 1988.

- Todorov, Tzvetan: The Inner Enemies of Democracy. Cambridge 2014.

Webressourcen

- The Guardian: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/mar/11/battle-britain-history-new-uk-citizens (last accessed 06. November 2016).

- politics.co.uk: http://www.politics.co.uk/news/2010/10/5/gove-schools-will-stop-trashing-our-past (last accessed 06. November 2016).

_____________________

[1] Danto, Arthur. Narration and Knowledge. New York: Columbia University Press, 2007.

[2] Megill, Allan. ‘Recounting the Past: “Description,” Explanation, and Narrative in Historiography’. The American Historical Review, 94 (3) 1989, S. 627-653.

[3] Carr, David. Experience and History: Phenomenological perspectives on the historicized world. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

[4] Todorov, Tzvetan. Hope and Memory: Reflections on the 20th Century. London: Atlantic Books, 2003, S.144.

[5] Levi, Primo. The Drowned and The Saved, London: Abacus, 1988, S.23.

[6] Edgar, David. (2013, March 11). The British history new citizens must learn: no radicals, no homosexuals, no Holocaust. The Guardian. Abgerufen von http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/mar/11/battle-britain-history-new-uk-citizens (letzter Zugriff am 27. Oktober 2016).

[7] Wozniak, Peter. Gove: Schools will ‘stop trashing our past’. Politics.Co.UK, 5 October 2010. Retrieved from http://www.politics.co.uk/news/2010/10/5/gove-schools-will-stop-trashing-our-past (letzter Zugriff am 27. Oktober 2016).

[8] Connolly, Kate. Neil MacGregor: ‘Britain forgets its past. Germany confronts it’. The Guardian, 7. Oktober 2016. Abgerufen von: https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2016/oct/07/britains-view-of-its-history-dangerous-says-former-museum-director (letzter Zugriff am 27. 2016)

[9] O’Neill, Brendan. Never mind Rhodes – it’s the cult of the victim that must fall. Spiked, 28. Dezember 2015. Abgerufen von: https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2016/oct/07/britains-view-of-its-history-dangerous-says-former-museum-director (letzter Zugriff am 27. Oktober 2016).

[10] Mann, Michael. The Sources of Social Power, Volumes I-IV. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

[11] Whitman, Walt. The Leaves of Grass. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990, S.78.

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

© Arthur Chapman

Übersetzung aus dem Englischen

Kurt Brügger swiss american language expert

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Chapman, Arthur: Zur Diagnose und Behebung von narrativen Untugenden. In: Public History Weekly 4. (2016) 37, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-7659

Copyright (c) 2016 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 4 (2016) 37

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-7659

Tags: Narratology (Narrativitätstheorie), Theory (Theorie), UK (Grossbritannien)

As a german history teacher in Chile I was delightetd about the insights of the article and furthermore about the image showing a street in my neigbourhood in Chile. A very simple example of the “participation in multiple, overlapping and often somewhat contradictory networks of interaction” in a globalized world. Thank you!

Thank you for comment. It was my privilege to visit Valparaiso in October and, I confess, I wrote much of this article in Santiago and Charles de Gaulle airports (in “limbo” and neither “here” nor “there”).

I included this picture as a homage to a beautiful city but also because it is full of “binaries”: two contrasting graffiti faces; two roads to choose from (one open, the other blocked); one half of the image in shaddow and the other in light; one side of the street “sacred” (the church) and the other “profane” (housing). These are fanciful interpretations of the image, I know, but it amused me, as I “found” the contrasts, to note how readily the mind sees binaries.