Abstract: The Anzac legend is Australia’s most popular historical narrative, but also requires examination as a homogenising, caricatured account of the country’s past. This offers opportunities and challenges for educators. Anzac’s appeal produces strong student engagement in the classroom and online. Entrenched ideas generate resistance to critique. Research focused assessment can leverage engagement to encourage critical thinking and transformative learning.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21039

Languages: English

This article reports on an undergraduate public history research project on war memorials in Australia, drawing on a framework of historical learning expounded by Raphael Samuel. Samuel believes that “history is not the prerogative of the historian … it is, rather, a social form of knowledge; the work, in any given instance, of a thousand pairs of hands.”[1]

In a related argument, Christoph Kühberger suggests that “it is quite unlikely that a sustainable, critical study of history can take place by ignoring historical interpretations which we encounter in everyday life.”[2] For Samuel, we can do this through “an attempt to follow the imaginative dislocations which take place when historical knowledge is transferred from one learning circuit to another.”[3] In these multivalent and overlapping “circuits”, history is transcribed, retold, remade and circulated – often outside of academia by, and for, the general public.

Anzac Narrative

In Australia, there is no more prominent example of public history making and re-making than the Anzac legend. This has been described as a “civic religion” that exalts idealised features of an Australian national type. Its characteristics include mateship, egalitarianism, irreverence, and scepticism towards authority.

Historians have presented a number of arguments for its popularity such as the state’s interventionist role in school curriculums, the influence of popular cultural products like Peter Weir’s film Gallipoli, and the need for a unifying narrative in an era of globalisation. Others have pointed to the growing popularity of genealogy and family history, as well as familial connections to soldiers and the military.[4]

These represent learning circuits that have had a clear influence on undergraduate students’ historical understanding. In the first week of classes, many of our students described Anzacs as “true heroes” who sacrificed their lives for Australia, or “us”. The Anzac legend, one noted, “is something that everyone has grown up with.” This historical understanding is notable for being generalised, cliched and lacking in detail.

Memorial Project

The memorial research project offers students an opportunity to dig beneath the legend and to analyse memorialisation in Australia. Students are asked to photograph a local war memorial and the names inscribed upon it. They type the names of soldiers into a spreadsheet and gather information about them through online nominal roles and databases. They then write a report on the memorial and the soldiers it commemorates. In it, they interrogate the design, location and community role of the memorial. They also describe and analyse the demographic features, war records and fate of the memorial’s soldiers.

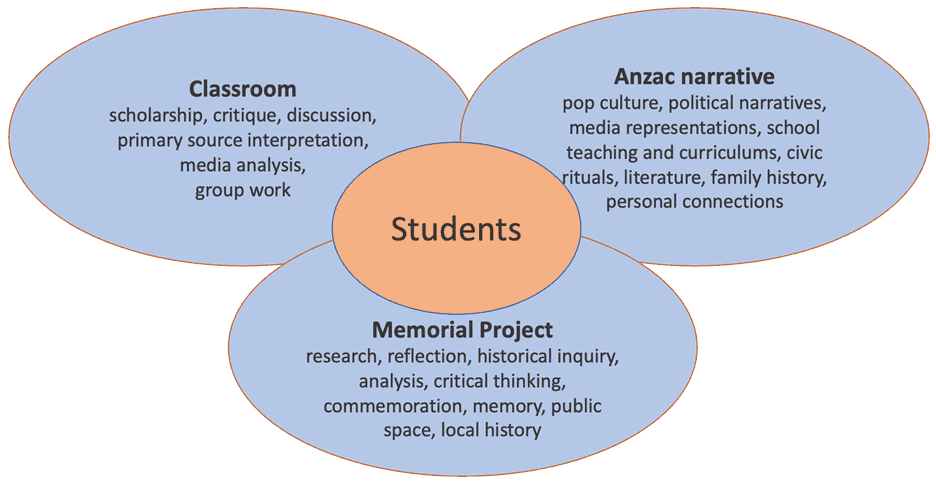

By connecting classroom learning, personal and cultural understandings of Anzac, and memorialisation, the project situates students at an intersection between different learning circuits (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Anzac Learning Circuits

Learning Circuits

Kühberger argues that students bring public history into the classroom from their own life experience.[5] In our case study, students arrive to class well versed in the Anzac narrative which they have developed through personal experience. They then encounter a different vocabulary and approach in the classroom, where the dominant narrative is critiqued and discussed.

This represents the intersection of two different learning circuits. The memorial project generates an additional, overlapping learning circuit by scaffolding applied historical inquiry into familiar but opaque local landmarks. Fig. 1 indicates these learning circuits and some of their constituent components.

Connecting and Critiquing Learning Circuits

The classroom learning circuit encourages students to think critically about representations of Anzac. The research project then asks students to identify, locate, access and critique material sources that further disrupt popular understandings. This research task –in which students observe, dig for detail and connect to context – attempts to reproduce what Samuel calls “elementary training in deconstruction.”[6] It also aligns with Kühberger’s argument that critical analysis of a wide range of real-world historical representations can enhance critical thinking skills.

After completing the memorial research project, our students told us that they thought more deeply about ideas, public spaces and memorials that they had previously taken for granted. Many described a new interest in local history and a connection to place as a result of their research. They said that this added complexity to a history that they had tended to understand in generalised terms, and helped them connect local monuments to the broader process of memorialisation in Australia. Others indicated that the research skills they acquired and the interest the project generated motivated them to undertake further local history research.

Based on this feedback, the project appears to have met its aim of engaging students and developing more nuanced understandings of the Anzac story.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Anna Clark, “The Place of Anzac in Australian Historical Consciousness,” Australian Historical Studies, 48(1) (2017): 19–34, 10.1080/1031461X.2016.1250790.

- Carolyn Holbrook, “Family History, Great War Memory and the ANZAC Revival,” Social Alternatives 37(3) (2018): 19–25.

- Paul Ashton and Paula Hamilton, “Places of the Heart: Memorials, Public History and the State in Australia Since 1960,” Public History Review 15 (2008): 1–29.

Web Resources

- AIF Project, University of NSW, Canberra: https://www.aif.adfa.edu.au/index.html (last accessed 1 December 2022)

- Anzac Portal, Australian Government Department of Veterans Affairs: https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/wars-and-missions/ww1/personnel/anzac-legend (last accessed 1 December 2022)

- Virtual War Memorial Australia: https://vwma.org.au/ (last accessed 1 December 2022)

_____________________

[1] Raphael Samuel, Theatres of Memory (London; New York: Verso 1994), 8.

[2] Christoph Kühberger, “The Private Use of Public History and its Effects on the Classroom”, in Public History and School: International Perspectives, ed. Marko Demantowsky (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018), 70.

[3] Samuel, Theatres of Memory, 8.

[4] Carolyn Holbrook, “The Anzac Legend in Australian Society: Recent Historiographical Debates,” Teaching History 53, no. 1 (2019): 4–8.

[5] Cited in Daisy Martin, “Teaching, Learning, and Understanding of Public History in Schools as Challenge for Students and Teachers,” in Public History and School: International Perspectives, ed. Marko Demantowsky (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018), 85.

[6] Samuel, Theatres of Memory, 278.

_____________________

Image Credits

Title image: ANZAC memorial © Heather Sharp personal collection.

Figure 1: Anzac Learning Circuits. © Authors.

Recommended Citation

Bailey Matthew, Sean Brawley: Student Learning Circuits, War Memorials and Anzac. In: Public History Weekly 11 (2023) 1, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21039.

Editorial Responsibility

Copyright © 2023 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 11 (2023) 1

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21039

Tags: Australia (Australien), Enquiry-based Learning (Forschend-entdeckendes Lernen), Memorials (Gedenkstätten), War (Krieg)

To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

OPEN PEER REVIEW

A Tool of Disruption

As a regular visitor to France and Italy in the 1980s just as the national interest in Anzac Day was revitalised after decades of dwindling interest, I visited numerous cathedrals and places of worship, both Christian and pagan. Perhaps this reflected the modern incarnation of my own Grand Tour, so popular between the 19th and 20th centuries, but it was not driven by any exceptionally strong religious impulse. It was, nevertheless, far from being a unique predilection. How could anyone visit Rome without being exposed to the glories of the Renaissance, even if they do not share what Ken Inglis describes as “traditional impulses towards faith and worship.”[1] Yet in my case, I spent just as much time on Great War battlefields and in Commonwealth War Cemeteries as I did in cathedrals; nevertheless, I gave little thought to the work of researchers such as Billings who characterise Anzac Day as displaced Christianity.[2]

I was more sympathetic at the time to a view later articulated by Graham Seal, who in 2007 acknowledged that “while we embrace the notion and the power of the sacred in Anzac, we mostly refuse its religious dimensions.” Instead, he observes that while the “considerable state and military apparatus and popular sentiment that surrounds [Anzac Day] has invested [it] with the sacred through the concept of nation rather than through religion.”[3] In any case, at the time, fresh out of university and embarking on my first years as a classroom teacher, my engagement was at a much more surface level. Far more impact was wrought by the visual impact of the number of memorials rather than their religious or secular qualities; by the time I first visited the old Western Front, it was estimated there was one monument for every 30 soldiers killed. The comparable figure for France at the time was one memorial for every 45 soldiers killed.[4] It was the statistics of death and the visceral engagement with what I believed was a ‘lost generation’ that shaped what was, without doubt, an emotional rather than an intellectual engagement.

The article Student Learning Circuits, War Memorials and Anzac explores a classroom-based initiative that encourages undergraduate students to use local memorials, an underutilised educational opportunity, as a vehicle to generate a more nuanced approach to the Anzac story and presumably by extension the place of conflict in Australian history. In addition, the project will help students to acquire the skills necessary to critique the Anzac story, which like all cultural constructs, is a conflation of history and myth.[5] Too often, as historians have found with the zombie myths of Australian military history, it is the myth that has come to dominate popular understandings of a war now installed as a foundational moment in the nation’s history.[6] Indeed, it is “the liberal paradox of war” that in spite of the suffering, it is readily and widely imagined as a “constitutive dimension of our public morality.”[7] It is here, however, that any project that engages with local war memorials must confront both the opportunities and limitations of the most common public art in in the Australian commemorative landscape.[8]

Any use of local war memorials must contend with the fact that though a construction in stone may visually remain unchanged, how it is interpreted, and the value placed on it architecturally or thematically will inevitably change. The ideas it espouses are subject to change and no doubt the project will grapple with the challenge of disrupting students’ readiness to see in their permanence an ideology resistant to change. For the strength of the memorials constructed in the immediate post-war years “lay in the power of traditional languages, rituals, and forms to mediate bereavement.”[9] The emergence of counter memorials in the 1980s, and the tenuous efforts to memorialise the frontier wars, use what is in effect a different language, for indeed, they serve a different purpose. To assess a local war memorial likely to have been built in the inert-war years, students will likely need to be familiar with Edwardian classicism to ‘read’ a local memorial constructed in the inter-war years, just as they will need to contextualise absences such as the failure to include the figure of Great War nurses in anything other than a handful of memorials.[10]

The project’s commitment to grounding the student’s experience in acts of disruption is particularly promising. Equally promising is the grounding of the experience in real world historical representations and inculcating critical thinking skills, both vital considerations given the importance of defending the discipline against being weaponised by politicians. I applaud the author’s efforts to make use of war memorials as a tool of disruption rather than as a nation building exercise. One can pursue this noble end without denigrating the sacrifice of past generations.

_____

[1] Ken Inglis, Sacred Places (Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 2008), 7.

[2] Billings, B. S., Is Anzac Day an incidence of ‘Displaced Christianity’? Pacifica, 28(3) (2015): 229-242.

[3] Graham Seal, ANZAC: The sacred in the secular, Journal of Australian Studies, 31(91) (2007): 135.

[4] Michael Hedger, Public Sculpture in Australia. (Roseville East, NSW: Craftsman, 1995).

[5] Seal, The sacred in the secular, 5

[6] Craig Stockings (Eds.), Zombie myths of Australian military history. (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2010).

[7] Lilie Chouliaraki, The humanity of war: Iconic photojournalism of the battlefield, 1914–2012. Visual Communication, 12(3) (2013): 316).

[8] Alison Bedford, Richard Gehrmann, Martin Kerby, and Margaret Baguley, Conflict and the Australian commemorative landscape, Historical Encounters, 8(3) (2021), 13-26.

[9] Jay Winter, Sites of Memory Sites of Mourning. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

[10] Martin Kerby, Margaret Baguley, Allison Millward, & Catherine Dewhirst, Neither in ink nor in stone: Memorials to Australian Great War Nurses, Australian Art Education, 42(2), 2021, 184-200.