Abstract:

How have Herman Schiefelbein’s paintings influenced cultural identity and visual culture in Brazil? This article aims to establish how his paintings relate to identity and landscapes by articulating representations and memories in the public and private spheres. I argue that artworks go beyond the walls of museums and personal collections, requiring transmission and outreach work by historians and artists, as well as social involvement through public policies, in order to encourage and disseminate artistic practices in public and institutional spaces.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17822

Languages: Portuguese, English, Deutsch

Como um refugiado alemão da Primeira Guerra Mundial imigrou para o Brasil, cultivou a terra e se tornou um pintor talentoso que surpreendeu os críticos de arte e influenciou a identidade e a cultura visual no Brasil? E hoje, como as comunidades, inluindo as de origem alemã, refletem esse passado e as obras de arte de Hermann Schiefelbein (1885-1933)? Historiadores, artistas e públicos, que pensam coletivamente sobre as artes nos espaços públicos, podem oferecer algumas respostas.

Fora do obscurantismo?

A redescoberta das pinturas de Herman Schiefelbein (1885-1933) desperta a admiração das audiências e colecionadores. Eu mesmo fui contactado por uma avaliadora de obras de arte interessada em localizar e comprar obras do artista para um colecionador de outro país.[1]

As telas em estilo romântico, influenciadas pelos mestres da Academia de Belas Artes de Düsseldorf, Alemanha, retratam as paisagens e o cotidiano de imigrantes que colonizavam o Sul do Brasil no início do século XX. Hoje, algumas de suas telas ornamentam espaços públicos importantes, incluindo o Museu Oscar Niemeyer, Clube Curitibano e o Colégio Estadual do Paraná.

No entanto, essa redescoberta não retira o autor, suas obras ou o modo como interpretou a paisagem da obscuridade. O desafio que se coloca para o historiador público é compreender os diversos usos de suas telas e como elas impactam os públicos ao longo do tempo. As pinturas de Schiefelbein equivalem a janelas para o passado, abertas à interpretação e à construção social de sentidos com as audiências. Portanto, como as pinturas de Herman Schiefelbein influenciaram a identidade cultural e a cultura visual no Brasil?

O passado através de obras de arte

Como demonstrou Simon Schama, os usos, as apropriações e as representações simbólicas da paisagem podem muito bem ser estudadas pelas perspectivas cultural, política, artística e nacional.[2] Isto nos faz pensar que a história pública articulada à arte pública oferece uma excelente oportunidade para ampliar valores culturais e acrescentar significados às comunidades e aos espaços públicos.

As telas “O baile das raças” (1933) e “Carroças e Cavalos” foram incorporadas à identidade paranaense e à mitologia nacional. Naquele momento, criava-se uma “comunidade de sentidos” com o objetivo de influenciar o imaginário popular. A estratégia consistia em redirecionar a arte de circuitos restritos para o domínio público.[3] Quando o historiador analisa as telas de Schiefelbein e sua historicidade descobre retóricas identitárias complexas, as quais ele precisa refletir com as audiências.

O quadro a “O baile das raças” representava a harmonia entre grupos étnicos e um sentimento coletivo de afeição entre imigrantes e paranaenses. Mas o discurso e a realidade eram incompatíveis, assim como os estereótipos étnicos. Havia divergências entre as elites e os imigrantes, que incentivados a colonizar, não tinham a cidadania reconhecida. Afinal de contas, o modelo de nação branca e civilizada se espelhou na cultura francesa, na economia inglesa, no aburguesamento dos costumes, no mito da democracia racial e na política de imigração brasileira.[4]

fig. 1 Ernst Stinsoff’s house, Schiefelbein painting «Wedding of the Nations», Photo by Arthur Wischral

Herman Schiefelbein, refugiado e traumatizado pela Primeira Guerra Mundial em sua pátria natal, tornou-se colono no Brasil. Esta situação foi vista com desconfiança pelos críticos de arte. Apesar do menosprezo inicial o artista foi reconhecido a partir das exposições nas cidades de Curitiba e São Paulo. Mas o que ele registrou na emblemática tela “O baile das raças”? Pode-se sugerir que ele projetou em suas telas, fragmentos da memória, da identidade alemã e do cotidiano de imigrantes que procuravam se adaptar à nova vida no Brasil. Este argumento fica mais sólido ao constatarmos que o governo paranaense instituía, desde 1914, a “Festa das Colônias”.[5] Daí o título alternativo “Bodas das nações” representando um destes encontros anuais.

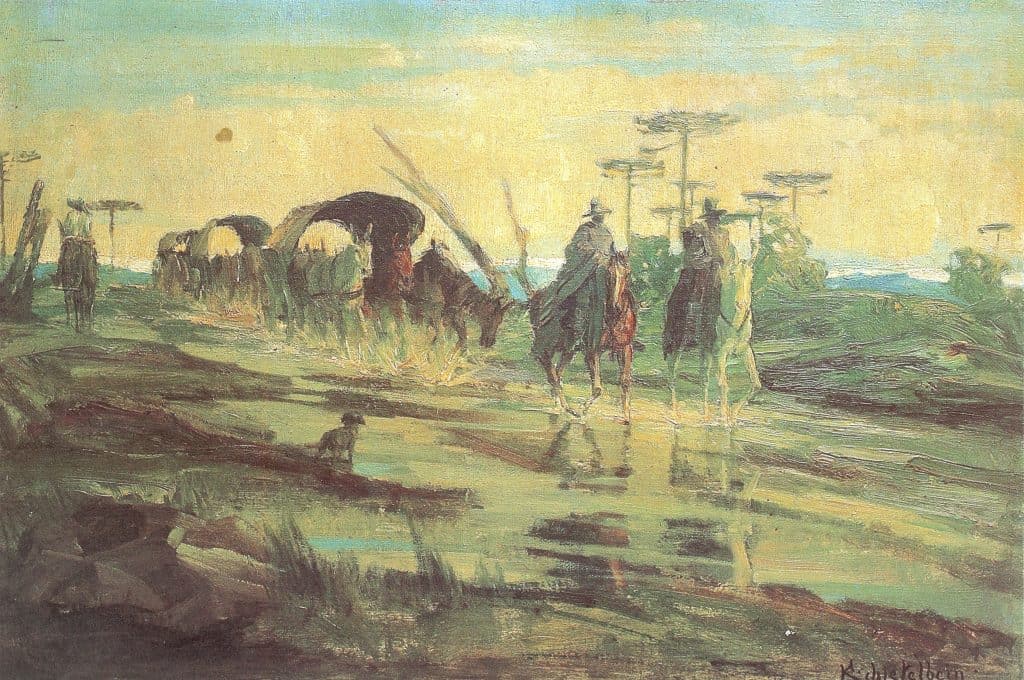

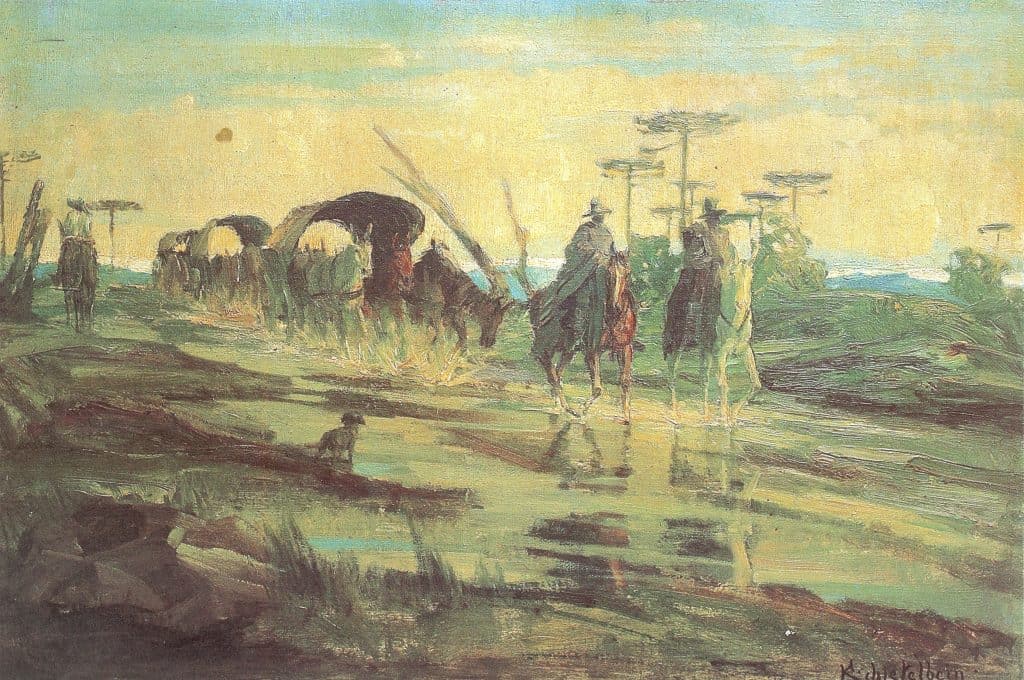

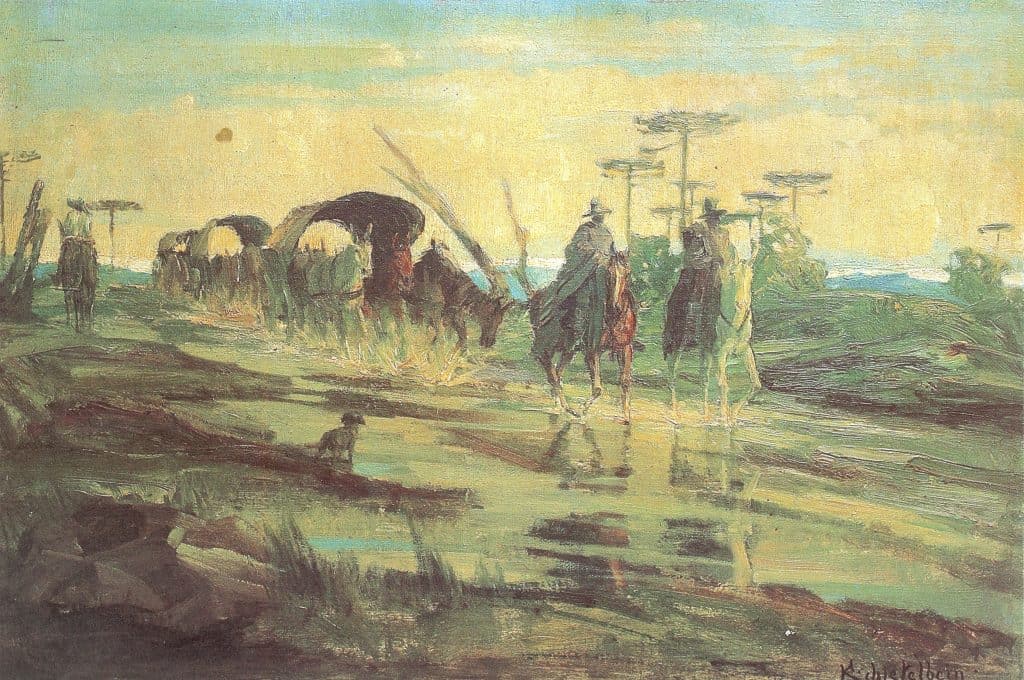

O quadro “Carroças e Cavalos” retrata a natureza de forma clara e fluida: terra, água da chuva, cão à espreita, cavalos em movimento, araucárias e céu nebuloso. É necessário salientar que os paranistas apreciaram as florestas, pinheiros e sementes de pinheiros, os quais se tornaram os símbolos oficiais do Estado do Paraná. Estes temas, recorrentes nas obras de Schiefelbein, podem ser explicados pela caraterística da paisagem paranaense: a floresta dos pinheirais. Contudo, a temática evoca a imigração eslava, exemplificada nos carroções em comboio. A paisagem também nos faz lembrar da condição de trânsito do artista e dos imigrantes no Brasil.

fig. 2 Wagons and Horses. Hermann Schiefelbein

O curioso é que esta pintura também pode auxiliar o historiador público a estudar a indumentária. Os homens representados na pintura ainda usam “poncho” e “bombacha”, traje este que, ao longo do tempo, tornou-se exclusividade da população do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul.[6] Isto porque os “paranistas” desejavam certa originalidade para o vestuário dos paranaenses. É muito provável que este tema seja oriundo de memórias da população local onde Schiefelbein viveu: Porto Vitória e União da Vitória. No século XVIII, estes lugares eram rota de passagem de comboios de animais que se dirigiam os mercados de Sorocaba (SP) e Minas Gerais para alimentar a escravidão e aumentar a extração de ouro.[7] Assim, podemos afirmar que a combinação entre germanidade e a colonização do Brasil resultou da apreensão da paisagem exuberante, da valorização da cultura e do conhecimento técnico e artístico dos alemães. A beleza cênica da paisagem foi considerada exuberante, uma dádiva divina. Mas ela só podia ser registrada pela fotografia e pela arte, as quais os alemães dominavam e desejavam ver avançar no Brasil, tornando-se públicas[8].

Revitalizações

Como demonstra Nancy Dallet é fundamental explorar os processos que ocorrem nas comunidades e criar novas formas de colaboração.[9] Historiadores públicos e artistas públicos podem colaborar, ampliar as reflexões sobre o passado e melhorar suas habilidades profissionais.

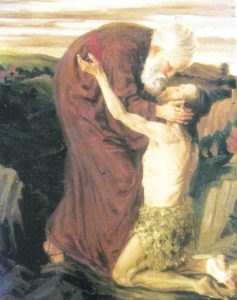

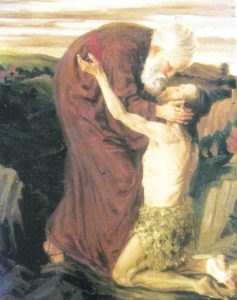

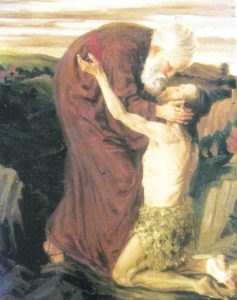

Na obra “Entrevistando a Arte”, Ivanira Olbertz e alunos do Ensino Fundamental mapearam centenas de pintores regionais, mesmo sem a expertise de historiadores.[10] Como a colaboração é fundamental para a prática da história pública realizei uma pesquisa de campo com a autora na comunidade rural da cidade de Porto Vitória (PR). Ali, constatamos que o consumo do passado entre descendentes de alemães também ocorre através de imagens. E que imagens encontramos? Reproduções da pintura de cunho religioso, isto é, “A volta do filho Pródigo”, de Schiefelbein. Com auxílio da comunidade foi possível localizarmos o túmulo do artista no “Cemitério Linha Bituruna”. Como destaca Jorge Kulemeyer, os imigrantes de origem alemã sempre tiveram uma forte tendência para a coesão comunitária e para manter ligações com as tradições.[11] Apesar dos vínculos memoriais e iconográficos a comunidade não conhecia bem o artista e as apropriações de suas pinturas. Ao constatarmos estes problemas elaboramos um plano de revitalização para este cemitério e um projeto histórico-artístico para ser aplicado em espaços públicos e escolares.

fig. 3 The Return of the Prodigal Son. Hermann Schiefelbein

fig. 4 Schiefelbein’s grave

Devido o avanço da Pandemia do Sars-Cov-19 as atividades se concentraram nas atividades online. No Simpósio Temático “Ensino de História, História Pública e as Redes Sociais”, da Associação Nacional dos Historiadores, apresentei o trabalho “História e Arte Pública em Herman Schiefelbein: da pintura da paisagem à produção de curta-metragem”. Partindo da ideia de mediação e de público colaborativo, familiares de Schiefelbein, residentes no Brasil, Portugal e Alemanha foram convidados para participar das discussões. Nesse encontro, Annelise Schiefelbein, neta do artista, enfatizou:

“É impressionante sua visão romântica…Ele teve seus estudos na Escola de Belas Artes de Düsseldorf interrompidos pela I Guerra Mundial. Trata-se de um povo que veio para o Brasil em meio a muito sofrimento, muita experiência traumática, provavelmente tendo mortes na família e sem dinheiro. Chegam a um local de difícil acesso e pelos quadros vemos quanta beleza ele vê. Há um sofrimento pessoal que não é necessariamente retratado na pintura. Há relatos aqui na Alemanha, de colegas e admiradores da arte que inicialmente ao verem suas obras não imaginavam que houvessem árvores, pôr do sol, a mata tropical e seu típico céu da forma como ele retratava. É muito legal ver a história do Paraná sendo retratada desta forma”.[12]

Arte e história

Os traços do movimento paranista ainda estão presentes no cotidiano dos paranaenses. A reprodução de seus símbolos evoca um sonho idílico sobre uma paisagem florestal que foi sendo devastada do longo da história. A recente instalação do “Memorial Pintor Amadeu Bona”, considerado “o pintor dos pinheirais” em União da Vitória, provocou polêmica ao desencadear disputas entre o lugar da arte no espaço público e as atividades econômicas informais.[13] Neste momento em que os monumentos são contestados em muitas partes do mundo é importante pensar no papel do historiador público e na arte como processo social.[14]

E se as obras de arte servem para questionar formas de inclusão e exclusão social, a ativação estética de valores culturais e identitários podem ser comprometidas se as ações com os públicos não forem realizadas de forma colaborativa. Aqui nós incluímos a produção coletiva de um curta-metragem.[15] Pensando nisto, lançamos o projeto “Histórias, Artes e públicos”. Entendemos que as obras de arte ultrapassam as paredes dos museus e das coleções pessoais. Elas podem ser vistas como formas de contestação aos usos do passado e das artes. Para isto, as mediações de historiadores públicos e de artistas públicos exigem envolvimento social e incentivo às práticas artísticas e históricas engajadas nos espaços públicos.[16]

_____________________

Leitura adicional

- Malcom Miles, “Art Space and the City: Public Art and Urban Futures” (London: Routledge, 1997).

- Michel Kobelinski, “Telas, Lentes e tramas: Registros da Identidade Teuto-brasileira no Paraná (séc. XX)” (Curitiba: Editora CRV, 2020).

- Rebecca Busch, and Paul K. Tawny, “Art and Public History: Approaches, Opportunities and Challenges” (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017).

Recursos da web

- Museu Oscar Niemeyer: “Paisagem com Figuras, por Hermann Schiefelbein (1885/1933)”, Website of the Museu Oscar Niemeyer, https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/landscape-with-figurines-hermann-schiefelbein/8AGcFTEwL3rM1g?hl=pt-br (last accessed 8 March 2021).

- Michel Kobelinski: “Histórias, Artes e Públicos”, https://historia.life/projetos (last accessed 8 March 2021).

_____________________

[1] A painting by Schiefelbein was on sale for approximately $14,000, https://produto.mercadolivre.com.br/MLB-714906602-obra-de-arte-herman-schiefelbein-35×55-_JM (last accessed 8 March 2021).

[2] Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory (Toronto: Random House of Canada, 1995). See also Jhon Gold, and Jacquelin Burges. Valued environments: essays on the place and landscape (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1992).

[3] O “Paranismo” foi um movimento intelectual, artístico, literário e político que construiu uma identidade simbólica, um sentimento de pertencimento e de amor pelo Estado do Paraná. Ver Cláudio Joaquim Rezende, ed., Paraná espaço e memória: diversos olhares histórico-geográficos (Curitiba: Editora Bagozzi, 2005).

[4] Luiz Felipe de Alencastro, and Maria Luiza Renaux. “Caras e modos dos migrantes e imigrantes”, in: História da vida privada no Brasil. Vol. 2: Império: a corte a modernidade nacional (São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1997), 303-305.

[5] PARANÁ. Lei 1.368 de 1914. Leis e Decretos do Estado. See Luis Fernando Pereira, Paranismo: Cultura e Imaginário no Paraná da I República (Curitiba: Universidade Federal do Paraná, 1996), 163, https://acervodigital.ufpr.br/bitstream/handle/1884/26993/D%20-%20PEREIRA,%20LUIS%20FERNANDO%20LOPES.pdf?sequence=1 (last accessed 8 March 2021).

[6] Adalice Araújo, Dicionário das Artes Plásticas no Paraná (Curitiba: Editora do Autor, 2006).

[7]. Jaelson Bitran Trindade, Tropeiros (São Paulo: Incepa, 1992).

[8] Michel Kobelinski, ‘Lugares de memória pública e retóricas da identidade teuto-brasileira no Estado do Paraná (séc. XX)’, Maracanan, no. 24 (2020), https://www.e-publicacoes.uerj.br/index.php/maracanan/article/view/47786 (last accessed 8 March 2021). See also Michel Kobelinski, ‘História, Cultura e religião: a Cidade Imperial e a região do Contestado nas apreensões de Estanislau Schaette e Hermann Schiefelbein (1926 1950)’, Revista Ensino & Pesquisa, no. 14 (2016), http://periodicos.unespar.edu.br/index.php/ensinoepesquisa/article/view/1190/622 (last accessed 8 March 2021).

[9] Nancy Dallet, “A Call for Proactive Public Historians”, in: Art and Public History: Approaches, Opportunities and Challenges’, ed. Busch, Rebecca, and Paul, K. Tawny (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017), 159-174.

[10] Ivanira Tereza Dias Olbertz, “Hermann Schiefelbein”, in: Entrevistando a Arte, Ivanira Tereza Dias Olbertz (Curitiba: Serzegraf, 2013), 138-142.

[11] Jorge Alberto Kulemeyer, “Prólogo”, in: Telas, Lentes e tramas: Registros da Identidade Teuto-brasileira no Paraná (séc. XX), Michel Kobelinski (Curitiba: Editora CRV, 2020), 15-17.

[12] Annelise Schiefelbein revisou e autorizou a publicação de seu testemunho.

[13] Antonio Budal, Inauguração da Praça Memorial Amadeu Bona (União da Vitória: TV Mil, dez, 2020), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kUj8EPi4JM8 (last accessed 8 March 2021).

[14] Malcon Miles. Art Space and the City: Public Art and Urban Futures (New York: Routledge, 1997).

[15] See an interesting example of interactive documentary creation: Thomas Cauvin, ‘Production Audio-Visuelle et Histoire Publique’, In: Public History Weekly 7 (2019) 16, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-13822.

[16] Suzanne Lacy, Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art (Seattle, Wash: Bay Press, 1995).

_____________________

Créditos da imagem

Featured Image: The letter. Hermann Schiefelbein. Collection of Edgar Schiefelbein.

fig. 1: Ernst Stinsoff’s house and Schiefelbein painting «Wedding of the Nations», Photo by Arthur Wischral. Collection Edgar Schiefelbein.

fig. 2: Wagons and Horses. Hermann Schiefelbein. Collection of the Paraná State College, Public Domain.

fig. 3: Reproduction, The Return of the Prodigal Son, Frithold Baumann’s collection, rights reserved by the author.

fig. 4: Schiefelbein’s grave © Michel Kobelinski.

Citação recomendada

Kobelinski, Michel: Arte Brasileira e identidade cultural em Schiefelbein? in: Public History Weekly 9 (2021) 3, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17822.

Responsabilidade editorial

How did a German after World War I immigrate to Brazil, cultivate land, and become a talented painter who surprised art critics and influenced visual identity and culture in Brazil? And today, how do communities, including those of German origin, reflect this past and the artworks of Hermann Schiefelbein (1885-1933)? Historians, artists, and the public, who collectively think about the arts in public spaces, may offer some answers.

Out of Obscurity?

The rediscovery of Herman Schiefelbein’s paintings has attracted both collectors and wider audiences. I myself have been contacted by an art dealer interested in finding and buying works by the artist for a collector from another country. [1]

Schiefelbein’s romantic-style paintings, influenced by various masters at Düsseldorf Academy of Fine Arts, depict southern Brazil’s landscapes and the everyday life of immigrants who settled there in the early 1920s. Today, some of these paintings adorn important public spaces (e.g. Oscar Niemeyer Museum, Clube Curitibano, and Paraná State College).

However, Schiefelbein’s rediscovery has brought neither the artist nor his works, nor his interpretation of landscape out of historical obscurity. Public historians are challenged to understand the diverse uses of his canvases and how they have impacted audiences over time. Schiefelbein’s paintings are windows into the past, open to both interpretation and the social construction of meaning among viewers. So how have Schiefelbein’s paintings influenced cultural identity and visual culture in Brazil?

The Past Through Art

Simon Schama has shown that the uses, appropriations, and symbolic representations of landscapes may be studied from cultural, political, artistic, and national perspectives.[2] Thus, public history, when articulated through public art, offers an excellent opportunity to extend cultural values and to add meaning to communities and public spaces.

The paintings “O baile das Raças” [Dance of the Races], produced in 1933, and “Carroças e Cavalos” [Wagons and Horses] were incorporated into the identity of the State of Paraná and Brazilian mythology. At that time, the sharing of interests, behaviors, and attitudes was idealized with the aim of influencing people’s imagination. The strategy was to redirect art from restricted circuits into the public domain.[3] Historians analyzing Schiefelbein’s paintings and their historicity discover a complex identity-based rhetoric, which they need to reflect on with audiences.

The painting “O baile das Raças” presents harmonious relations between ethnic groups and a collective feeling of affection between immigrants and locals. But discourse and reality were incompatible, as were ethnic stereotypes. There were divergences between elites and immigrants, as the latter, even though encouraged to settle the land, did not have their citizenship recognized. After all, the idea of a white, civilized nation was mirrored in French culture, in the English economy, in the gentrification of customs, in the myth of racial democracy, and in Brazil’s immigration policy.[4]

fig. 1 Ernst Stinsoff’s house, Schiefelbein painting «Wedding of the Nations», Photo by Arthur Wischral

Herman Schiefelbein, a immigrant traumatized by World War I in his homeland, became a settler in Brazil. This has been viewed with suspicion by art critics. Despite initial contempt, recognition came after exhibitions in the cities of Curitiba and São Paulo. But what did Schiefelbein place on record in his emblematic “O baile das Raças”? Arguably, he projected onto his canvases fragments of his memories, of his German identity, and of the daily lives of immigrants seeking to adapt to their new life in Brazil. This argument becomes more solid once we realize that the government of Paraná has been celebrating the “Festival of Settlements” since 1914[5] — hence the alternative title “Wedding of the Nations” — to represent one of these annual meetings.

The painting “Carroças e Cavalos” portrays nature in a clear and fluid way: earth, rainwater, a dog on the prowl, horses in motion, araucarias (Paraná pine trees) and a cloudy sky. The Paranistas appreciated forests, pine trees, and pine seeds, which have since become the official symbols of the State of Paraná. These themes, recurrent in Schiefelbein’s works, can be explained by the stand-out feature of the Paranáian landscape: pine forests. However, this theme evokes Slavic immigration, exemplified in wagon convoys. The landscape also reminds us of the transitory condition of artists and immigrants in Brazil.

fig. 2 Wagons and Horses. Hermann Schiefelbein

Curiously, this painting can also help public historians to study clothing. The men depicted are still wearing ponchos and bombachas, garments that, over time, became exclusive to the population of the State of Rio Grande do Sul.[6] This was because the Paranistas wanted their clothes to feature some originality. It is very likely that this theme stems from Schiefelbein’s memories of the local villages where he lived: Porto Vitória and União da Vitória. In the eighteenth century, these places were on the route along which animal convoys passed on their way to markets in São Paulo and Minas Gerais to feed the enslaved populations and to support gold mining.[7] Thus, their love of the exuberant landscape, their appreciation of culture, as well as their technical and artistic knowledge helped German immigrants to maintain their identity as settlers in Brazil. The scenic beauty of the landscapes was considered a lush godsend. But it could only be placed on record and handed down by photography and artworks, which where both firmly in German hands, and which they sought to advance in Brazil by making them public.[8]

Revitalisations

Nancy Dallet has shown that it is essential to explore the processes taking place within communities and to create new forms of collaboration.[9] Public historians and public artists can collaborate, broaden reflections on the past, and enhance their professional skills.

In “Interviewing Art,” Ivanira Olbertz and elementary school students mapped hundreds of local painters — without the expertise of historians.[10] Collaboration being fundamental to practicing public history, I conducted field research with Olbertz in the rural area of Porto Vitória (PR). We heard the descendants of German immigrants also reminisce about the past through images. And what images did we find? Well, reproductions of Schiefelbein’s religious painting “A Volta do Filho Pródigo”[The Return of the Prodigal Son]. Helped by the community, we were able to locate the artist’s grave in Linha Bituruna Cemetery. As Jorge Kulemeyer points out, German immigrants have always had a “strong tendency” to community cohesion and to maintaining the customs of their homeland.[11]

Despite its memorializing and iconographic ties, the community did not know Schiefelbein and his paintings very well. We therefore developed a revitalization plan for the cemetery and a historical-artistic project (to be conducted in schools and public spaces).

fig. 3 The Return of the Prodigal Son. Hermann Schiefelbein

fig. 4 Schiefelbein’s grave

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, activities ran mostly online. At the thematic symposium “History Teaching, Public History, and Social Media,” hosted by the Brazilian Association of Historians, I presented the paper “History and Public Art in Herman Schiefelbein: From Landscape Painting to Short Film Production.” Based on the ideas of art outreach and of a collaborative public, Schiefelbein’s relatives in Brazil, Portugal, and Germany were invited to participate in the discussions. At that meeting, Annelise Schiefelbein, the artist’s granddaughter, emphasized:

His romantic vision is impressive…His studies at Düsseldorf School of Fine Arts were interrupted by World War I. These are people who came to Brazil amid a lot of suffering, a lot of traumatic experiences, probably with deaths in the family and without money. They came to a remote place, and their paintings show us how much beauty they saw. There was personal suffering that is not necessarily portrayed in these paintings. There are reports here in Germany, of colleagues and art admirers who, before seeing his artworks, did not imagine that there were trees, sunsets, the rainforest, and its typical sky as he portrayed them. It is very nice to see the history of Paraná being depicted in this way.[12]

Art and History

Traces of the Paranista sentiment are still present in everyday life in Paraná. The reproduction of their symbols evokes an idyllic dream about a forest landscape devastated throughout history. The recent launch of a memorial for Amadeu Bona, an artist famous for his paintings of pine trees in União da Vitória, sparked controversy and a dispute over the role of art in public spaces and informal economic activities.[13] Today, when monuments are being contested across the world, we need to consider the role of public historians and art as a social process.[14]

And if artworks serve to question forms of social inclusion and exclusion, the aesthetic activation of cultural and identity values can be compromised if actions toward the public are not carried out collaboratively. On this note, I refer briefly to the collective production of a short film.[15] With this in mind, we launched the project “Stories, Arts and Audiences” to highlight that artworks reach beyond museums and personal collections. These works, including Schiefelbein’s, can be seen as a means of challenging how the past and the arts are used. To this end, the outreach work of public historians and public artists requires social commitment, among others, encouraging engaged artistic and historical practices in public spaces.[16]

_____________________

Further Reading

- Malcom Miles, “Art Space and the City: Public Art and Urban Futures” (London: Routledge, 1997).

- Michel Kobelinski, “Telas, Lentes e tramas: Registros da Identidade Teuto-brasileira no Paraná (séc. XX)” (Curitiba: Editora CRV, 2020).

- Rebecca Busch, and Paul K. Tawny, “Art and Public History: Approaches, Opportunities and Challenges” (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017).

Web Resources

- Museu Oscar Niemeyer: “Paisagem com Figuras, por Hermann Schiefelbein (1885/1933)”, Website of the Museu Oscar Niemeyer, https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/landscape-with-figurines-hermann-schiefelbein/8AGcFTEwL3rM1g?hl=pt-br (last accessed 8 March 2021).

- Michel Kobelinski: “Histórias, Artes e Públicos”, https://historia.life/projetos (last accessed 8 March 2021).

_____________________

[1] A painting by Schiefelbein was on sale for approximately $14,000, https://produto.mercadolivre.com.br/MLB-714906602-obra-de-arte-herman-schiefelbein-35×55-_JM (last accessed 8 March 2021).

[2] Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory (Toronto: Random House of Canada, 1995). See also Jhon Gold, and Jacquelin Burges. Valued environments: essays on the place and landscape (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1992).

[3] O “Paranismo” foi um movimento intelectual, artístico, literário e político que construiu uma identidade simbólica, um sentimento de pertencimento e de amor pelo Estado do Paraná. Ver Cláudio Joaquim Rezende, ed., Paraná espaço e memória: diversos olhares histórico-geográficos (Curitiba: Editora Bagozzi, 2005).

[4] Luiz Felipe de Alencastro, and Maria Luiza Renaux. “Caras e modos dos migrantes e imigrantes”, in: História da vida privada no Brasil. Vol. 2: Império: a corte a modernidade nacional (São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1997), 303-305.

[5] PARANÁ. Lei 1.368 de 1914. Leis e Decretos do Estado. See Luis Fernando Pereira, Paranismo: Cultura e Imaginário no Paraná da I República (Curitiba: Universidade Federal do Paraná, 1996), 163, https://acervodigital.ufpr.br/bitstream/handle/1884/26993/D%20-%20PEREIRA,%20LUIS%20FERNANDO%20LOPES.pdf?sequence=1 (last accessed 8 March 2021).

[6] Adalice Araújo, Dicionário das Artes Plásticas no Paraná (Curitiba: Editora do Autor, 2006).

[7]. Jaelson Bitran Trindade, Tropeiros (São Paulo: Incepa, 1992).

[8] Michel Kobelinski, ‘Lugares de memória pública e retóricas da identidade teuto-brasileira no Estado do Paraná (séc. XX)’, Maracanan, no. 24 (2020), https://www.e-publicacoes.uerj.br/index.php/maracanan/article/view/47786 (last accessed 8 March 2021). See also Michel Kobelinski, ‘História, Cultura e religião: a Cidade Imperial e a região do Contestado nas apreensões de Estanislau Schaette e Hermann Schiefelbein (1926 1950)’, Revista Ensino & Pesquisa, no. 14 (2016), http://periodicos.unespar.edu.br/index.php/ensinoepesquisa/article/view/1190/622 (last accessed 8 March 2021).

[9] Nancy Dallet, “A Call for Proactive Public Historians”, in: Art and Public History: Approaches, Opportunities and Challenges’, ed. Busch, Rebecca, and Paul, K. Tawny (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017), 159-174.

[10] Ivanira Tereza Dias Olbertz, “Hermann Schiefelbein”, in: Entrevistando a Arte, Ivanira Tereza Dias Olbertz (Curitiba: Serzegraf, 2013), 138-142.

[11] Jorge Alberto Kulemeyer, “Prólogo”, in: Telas, Lentes e tramas: Registros da Identidade Teuto-brasileira no Paraná (séc. XX), Michel Kobelinski (Curitiba: Editora CRV, 2020), 15-17.

[12] Annelise Schiefelbein revisou e autorizou a publicação de seu testemunho.

[13] Antonio Budal, Inauguração da Praça Memorial Amadeu Bona (União da Vitória: TV Mil, dez, 2020), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kUj8EPi4JM8 (last accessed 8 March 2021).

[14] Malcon Miles. Art Space and the City: Public Art and Urban Futures (New York: Routledge, 1997).

[15] See an interesting example of interactive documentary creation: Thomas Cauvin, ‘Production Audio-Visuelle et Histoire Publique’, In: Public History Weekly 7 (2019) 16, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-13822.

[16] Suzanne Lacy, Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art (Seattle, Wash: Bay Press, 1995).

_____________________

Image Credits

Featured Image: The letter. Hermann Schiefelbein. Collection of Edgar Schiefelbein.

fig. 1: Ernst Stinsoff’s house and Schiefelbein painting «Wedding of the Nations», Photo by Arthur Wischral. Collection Edgar Schiefelbein.

fig. 2: Wagons and Horses. Hermann Schiefelbein. Collection of the Paraná State College, Public Domain.

fig. 3: Reproduction, The Return of the Prodigal Son, Frithold Baumann’s collection, rights reserved by the author.

fig. 4: Schiefelbein’s grave © Michel Kobelinski.

Recommended Citation

Kobelinski, Michel: Brazilian Art and Cultural Identity by Schiefelbein? in: Public History Weekly 9 (2021) 3, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17822.

Editorial Responsibility

Wie konnte ein Deutscher nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg nach Brasilien einwandern, Land kultivieren und ein talentierter Maler werden, der Kunstkritiker:innen überraschte und die visuelle Identität und Kultur in Brasilien beeinflusste? Und wie reflektieren heutige Gemeinschaften in Brasilien, auch deutschstämmige, diese Vergangenheit und die Kunstwerke von Hermann Schiefelbein (1885–1933)? Historiker:innen, Künstler:innen und die Öffentlichkeit, die gemeinsam über die Kunst im öffentlichen Raum nachdenken, können dazu einige Antworten geben.

Aus der Vergessenheit geholt?

Die Wiederentdeckung der Gemälde von Herman Schiefelbein (1885–1933) hat Bewunderung unter Sammler:innen und einem breiteren Publikum ausgelöst. Neulich kontaktierte mich ein Kunstsachverständiger, da er Schiefelbeins Kunstwerke für einen Sammler aus einem anderen Land ausfindig machen und erwerben wollte.[1]

Schiefelbeins Gemälde, im romantischen Stil gehalten und von Meistern der Düsseldorfer Kunstakademie beeinflusst, stellen Landschaften und das tägliche Leben von Einwanderer:innen dar, die sich in den frühen 1920er Jahren im Süden Brasiliens niederliessen. Heute schmücken einige seiner Gemälde wichtige öffentliche Räume, darunter das Oscar Niemeyer Museum, der Clube Curitibano und das Paraná State College.

Jedoch holt die Wiederentdeckung in diesen Zusammenhängen weder Schiefelbein noch seine Kunstwerke oder die Art und Weise, wie er die Landschaft Südbrasiliens interpretierte, aus der historischen Vergessenheit. Historiker:innen stehen vor der Herausforderung, die vielfältigen Verwendungen seiner Gemälde zu verstehen und wie sie das Publikum im Laufe der Zeit beeinflusst haben. Schiefelbeins Gemälde sind Fenster in die Vergangenheit, offen für Interpretationen und für die soziale Konstruktion von Bedeutung durch sein Publikum. Wie haben diese Gemälde die kulturelle Identität und die visuelle Kultur in Brasilien beeinflusst?

Zur Vergangenheit durch Kunst

Wie Simon Schama gezeigt hat, können die Verwendungen, Aneignungen und symbolischen Darstellungen von Landschaften aus kultureller, politischer, künstlerischer und nationaler Perspektive untersucht werden.[2] Ich glaube deshalb, dass Public History, wenn sie sich als öffentliche Kunst artikuliert, eine hervorragende Möglichkeit bietet, kulturelle Werte zu erweitern und sowohl Gemeinschaften als auch öffentlichen Räumen Bedeutung zu geben.

Die Gemälde “O baile das Raças” [Tanz der Rassen], entstanden im Jahr 1933, und “Carroças e Cavalos” [Wagen und Pferde] wurden in die Identität des Staates Paraná und in die brasilianische Mythologie aufgenommen. Geteilte Interessen, Verhaltensweisen und Einstellungen idealisierte man damals mit dem Ziel, die menschliche Vorstellungskraft zu beeinflussen. Die Strategie bestand darin, die Kunst aus begrenzten Kreisen in den öffentlichen Bereich zu überführen.[3] Wenn Historiker:innen Schiefelbeins Bilder und ihre Historizität untersuchen, entdecken sie eine komplexe identitätsbasierte Rhetorik, die sie gemeinsam mit den Betrachter:innen dieser Kunst reflektieren müssen.

Das Gemälde “O baile das Raças” stellt die Harmonie zwischen ethnischen Gruppen und ein kollektives Gefühl der Zuneigung zwischen Einwanderer:innen und Einheimischen dar. Jedoch waren Diskurs und Realität unvereinbar, ebenso wie die ethnischen Stereotypen. Es gab Divergenzen zwischen Eliten und Einwanderer:innen, da letztere, obwohl sie zur Besiedlung des Landes ermutigt wurden, ihre Staatsbürgerschaft nicht anerkannt bekamen. Schliesslich spiegelte sich die Idee einer weissen, zivilisierten Nation in der französischen Kultur, in der englischen Wirtschaft, in der Gentrifizierung der Sitten, im Mythos der Rassendemokratie und in der brasilianischen Einwanderungspolitik wider[4].

fig. 1 Ernst Stinsoffs Haus, Schiefelbein painting «Wedding of the Nations», Photo by Arthur Wischral

Hermann Schiefelbein, ein deutscher Immigrant, der in seiner Vaterland durch den Ersten Weltkrieg traumatisiert worden war, wurde Siedler in Brasilien. Dieser Umstand wurde von Kunstkritiker:innen mit Misstrauen betrachtet. Trotz anfänglicher Verachtung verhalfen Ausstellungen in den Städten Curitiba und São Paulo Schiefelbein zur Anerkennung. Doch was hat er in seinem emblematischen Bild “O baile das Raças” festgehalten? Man könnte vermuten, dass er auf seine Leinwände Fragmente seiner Erinnerungen, seiner deutschen Identität und des Alltags von Einwanderer:innen projizierte, die versuchen, sich an ihr neues Leben in Brasilien anzupassen. Dieses Argument erhärtet sich, wenn man bedenkt, dass die Regierung von Paraná seit 1914 das “Fest der Siedlungen”[5] feierte — daher die alternative Bezeichnung “Hochzeit der Nationen,” um eines dieser jährlichen Treffen darzustellen.

Schiefelbeins “Carroças e Cavalos” stellt die Natur klar und fliessend dar: Erde, Regenwasser, ein Hund auf der Pirsch, Pferde in Bewegung, Araukarien (Paraná-Kiefern) und ein bewölkter Himmel. Dabei sollte betont werden, dass die Paranistas die umgebenden Wälder, Kiefern und Kiefernsamen wertschätzten, die zu den offiziellen Symbolen des Staates Paraná geworden sind. Diese Themen, die in Schiefelbeins Werken immer wieder auftauchen, lassen sich durch das Hauptmerkmal der Landschaft von Paraná erklären: Kiefernwälder. Dieses Thema erinnert aber auch an die slawische Einwanderung, die in den Wagenkolonnen zum Ausdruck kommt. Die Landschaft erinnert auch an den transitorischen Zustand von Künstler:innen und Migrant:innen in Brasilien.

fig. 2 Wagen and Pferde. Hermann Schiefelbein

Kurioserweise kann dieses Gemälde auch Public Historians helfen, die Bekleidung jener Zeit genauer zu betrachten. Die auf dem Gemälde dargestellten Männer tragen immer noch Ponchos und Bombachas, Kleidungsstücke, die im Laufe der Zeit ausschliesslich von der Bevölkerung des Bundesstaates Rio Grande do Sul getragen wurden.[6] Dies lag daran, dass die Paranistas ihre Kleidung mit einer gewissen Originalität versehen wollten. Es ist sehr wahrscheinlich, dass dieses Thema aus den Erinnerungen der beiden Dörfer stammt, in denen Schiefelbein lebte: Porto Vitória und União da Vitória. Im achtzehnten Jahrhundert lagen diese Orte an der Durchgangsroute von Tierkonvois, die zu den Märkten in São Paulo und Minas Gerais fuhren, um die versklavte Bevölkerung zu ernähren und beim Goldabbau zu helfen.[7]

Die Liebe der deutschen Einwanderer:innen zur üppigen Landschaft, ihre Wertschätzung der Kultur und ihre technischen und künstlerischen Kenntnisse halfen ihnen dabei, ihre Identität als Siedler:innen in Brasilien zu bewahren. Die szenische Schönheit der Landschaften galt als opulentes Gottesgeschenk. Allerdings konnte diese Schönheit nur durch die Fotografie und in Kunstwerken festhalten werden. Bei beiden Formen waren deutschen Siedler:innen vorherrschend und durch deren Veröffentlichung wollten sie sich in ihrer neuen Heimat durchsetzen.[8]

Revitalisierungen

Nancy Dallet hat dargelegt, wie wichtig es ist, die Prozesse, die innerhalb von Gemeinschaften stattfinden, zu erforschen und neue Formen der Zusammenarbeit zu schaffen.[9] Public Historians können mit Künstler:innen zusammenarbeiten die Kunst im öffentlichen Raum machen, und so die Reflexion über die Vergangenheit erweitern und ihre beruflichen Kompetenzen verbessern.

In “Interviewing Art” hat Ivanira Olbertz mit Grundschüler:innen Hunderte von lokalen Maler:innen kartographisch erfasst, sogar ohne die Expertise von Historiker:innen.[10] Da Zusammenarbeit grundlegend ist, um Public History zu praktizieren, habe ich mit der Autorin Feldforschung in der ländlichen Gegend von Porto Vitória (PR) betrieben. Dort sahen wir, dass auch deutsche Nachfahren sich mit Hilfe von Bildern an die Vergangenheit zurückerinnern. Welche Bilder haben wir gefunden? Reproduktionen von “A Volta do Filho Pródigo” [Die Rückkehr des verlorenen Sohnes], ein religiöses Gemälde von Schiefelbein. Die Gemeinde half uns, das Grab des Künstlers auf dem Friedhof von Linha Bituruna ausfindig zu machen. Wie Jorge Kulemeyer hervorhebt, hatten die deutschstämmigen Einwanderer:innen schon immer eine “starke Tendenz” zum gemeinschaftlichen Zusammenhalt und zur Aufrechterhaltung der Bräuche ihres Herkunftslandes.[11]

Trotz des Erinnerungsorts und der ikonografischen Verknüpfungen kannte die Gemeinde weder der Künstler noch seine Bilder besonders gut. Indem wir diese Herausforderungen feststellten, entwickelten wir einen Revitalisierungsplan für den Friedhof und ein historisch-künstlerisches Projekt, das in Schulen und öffentlichen Räumen durchgeführt werden soll.

fig. 3 Die Rückkehr das verlorenen Sohns. Hermann Schiefelbein

fig. 4 Schiefelbeins Grab

Aufgrund der Covid-19-Pandemie fanden die Aktivitäten hauptsächlich online statt. Im Rahmen des Symposiums “History Teaching, Public History, and Social Media,” das vom brasilianischen Historiker:innenverband veranstaltet wurde, präsentierte ich den Beitrag “History and Public Art in Herman Schiefelbein: From Landscape Painting to Short Film Production”. Basierend auf den Ideen der Vermittlung und einer kollaborativen Öffentlichkeit wurden Schiefelbeins Verwandte, die in Brasilien, Portugal und Deutschland leben, eingeladen, an den Diskussionen teilzunehmen. Anneliese Schiefelbein, die Enkelin des Künstlers, hob anlässlich dieses Treffens hervor:

Seine romantische Vision ist beeindruckend…Sein Studium an der Düsseldorfer Kunsthochschule wurde durch den Ersten Weltkrieg unterbrochen. Das sind Menschen, die inmitten von viel Leid, vielen traumatischen Erfahrungen, wahrscheinlich mit Todesfällen in der Familie und ohne Geld nach Brasilien kamen. Sie kommen an einem abgelegenen Ort an, und ihre Bilder zeigen uns, wie viel Schönheit sie sehen. Es gibt persönliches Leid, das nicht unbedingt in der Malerei abgebildet ist. Es gibt Berichte hier in Deutschland, von Kollegen und Kunstliebhabern, die sich, bevor sie seine Kunstwerke sahen, nicht vorstellen konnten, dass es Bäume, Sonnenuntergänge, den Regenwald und seinen typischen Himmel in der Art und Weise gibt, wie er sie dargestellt hat. Es ist sehr schön zu sehen, dass die Geschichte von Paraná auf diese Weise dargestellt wird.[12]

Kunst und Geschichte

Spuren des Paranista-Lebensgefühls sind im täglichen Leben in Paraná immer noch präsent. Die Wiedergabe ihrer Symbole evoziert einen idyllischen Traum über eine Waldlandschaft, die im Laufe der Geschichte verwüstet wurde. Die kürzliche Einweihung eines Denkmals für den Maler Amadeu Bona, der für seine Pinienbilder in União da Vitória berühmt ist, löste eine Kontroverse aus über den Platz der Kunst im öffentlichen Raum und informellen wirtschaftlichen Aktivitäten.[13] Heuzutage, wo weltweit Denkmäler umstritten sind, ist es wichtig, über die Rolle des Public Historians und über Kunst als sozialen Prozess nachzudenken.[14]

Und wenn Kunstwerke dazu dienen, Formen der sozialen Inklusion und Exklusion zu hinterfragen, kann die ästhetische Aktivierung kultureller und identitätsstiftender Werte gefährdet sein, wenn die Aktionen gegenüber der Öffentlichkeit nicht kollaborativ durchgeführt werden. An dieser Stelle verweise ich auf die kollektive Produktion eines Kurzfilms zum Thema.[15] In diesem Sinne haben wir das Projekt “Stories, Arts and Audiences” ins Leben gerufen. Es zeigt u.a., dass Kunstwerke über Museen und persönliche Sammlungen hinausreichen. Solche Werke, einschliesslich jene von Hermann Schiefelbein, können als Formen gesehen werden, die zu hinterfragen helfen, wie die Vergangenheit und die Künste interessiert genutzt werden. Die gemeinsame Arbeit von Historikern und Künstlern im öffentlichen Raum erfordert daher gesellschaftliches Engagement, nicht zuletzt durch die Förderung von engagierten künstlerischen und historischen Praktiken in der Öffentlichkeit.[16]

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Malcom Miles, “Art Space and the City: Public Art and Urban Futures” (London: Routledge, 1997).

- Michel Kobelinski, “Telas, Lentes e tramas: Registros da Identidade Teuto-brasileira no Paraná (séc. XX)” (Curitiba: Editora CRV, 2020).

- Rebecca Busch, and Paul K. Tawny, “Art and Public History: Approaches, Opportunities and Challenges” (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017).

Webressourcen

- Museu Oscar Niemeyer: “Paisagem com Figuras, por Hermann Schiefelbein (1885/1933)”, Website of the Museu Oscar Niemeyer, https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/landscape-with-figurines-hermann-schiefelbein/8AGcFTEwL3rM1g?hl=pt-br (letzter Zugriff 8. März 2021).

- Michel Kobelinski: “Histórias, Artes e Públicos”, https://historia.life/projetos (letzter Zugriff 8. März 2021).

_____________________

[1] A painting by Schiefelbein was on sale for approximately $14,000, https://produto.mercadolivre.com.br/MLB-714906602-obra-de-arte-herman-schiefelbein-35×55-_JM (letzter Zugriff 8. März 2021).

[2] Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory (Toronto: Random House of Canada, 1995). See also Jhon Gold, and Jacquelin Burges. Valued environments: essays on the place and landscape (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1992).

[3] O “Paranismo” foi um movimento intelectual, artístico, literário e político que construiu uma identidade simbólica, um sentimento de pertencimento e de amor pelo Estado do Paraná. Ver Cláudio Joaquim Rezende, ed., Paraná espaço e memória: diversos olhares histórico-geográficos (Curitiba: Editora Bagozzi, 2005).

[4] Luiz Felipe de Alencastro, and Maria Luiza Renaux. “Caras e modos dos migrantes e imigrantes”, in: História da vida privada no Brasil. Vol. 2: Império: a corte a modernidade nacional (São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1997), 303-305.

[5] PARANÁ. Lei 1.368 de 1914. Leis e Decretos do Estado. See Luis Fernando Pereira, Paranismo: Cultura e Imaginário no Paraná da I República (Curitiba: Universidade Federal do Paraná, 1996), 163, https://acervodigital.ufpr.br/bitstream/handle/1884/26993/D%20-%20PEREIRA,%20LUIS%20FERNANDO%20LOPES.pdf?sequence=1 (letzter Zugriff 8. März 2021).

[6] Adalice Araújo, Dicionário das Artes Plásticas no Paraná (Curitiba: Editora do Autor, 2006).

[7]. Jaelson Bitran Trindade, Tropeiros (São Paulo: Incepa, 1992).

[8] Michel Kobelinski, ‘Lugares de memória pública e retóricas da identidade teuto-brasileira no Estado do Paraná (séc. XX)’, Maracanan, no. 24 (2020), https://www.e-publicacoes.uerj.br/index.php/maracanan/article/view/47786 (letzter Zugriff 8. März 2021). See also Michel Kobelinski, ‘História, Cultura e religião: a Cidade Imperial e a região do Contestado nas apreensões de Estanislau Schaette e Hermann Schiefelbein (1926 1950)’, Revista Ensino & Pesquisa, no. 14 (2016), http://periodicos.unespar.edu.br/index.php/ensinoepesquisa/article/view/1190/622 (letzter Zugriff 8. März 2021).

[9] Nancy Dallet, “A Call for Proactive Public Historians”, in: Art and Public History: Approaches, Opportunities and Challenges’, ed. Busch, Rebecca, and Paul, K. Tawny (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017), 159-174.

[10] Ivanira Tereza Dias Olbertz, “Hermann Schiefelbein”, in: Entrevistando a Arte, Ivanira Tereza Dias Olbertz (Curitiba: Serzegraf, 2013), 138-142.

[11] Jorge Alberto Kulemeyer, “Prólogo”, in: Telas, Lentes e tramas: Registros da Identidade Teuto-brasileira no Paraná (séc. XX), Michel Kobelinski (Curitiba: Editora CRV, 2020), 15-17.

[12] Annelise Schiefelbein revisou e autorizou a publicação de seu testemunho.

[13] Antonio Budal, Inauguração da Praça Memorial Amadeu Bona (União da Vitória: TV Mil, dez, 2020), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kUj8EPi4JM8 (letzter Zugriff 8. März 2021).

[14] Malcon Miles. Art Space and the City: Public Art and Urban Futures (New York: Routledge, 1997).

[15] See an interesting example of interactive documentary creation: Thomas Cauvin, ‘Production Audio-Visuelle et Histoire Publique’, In: Public History Weekly 7 (2019) 16, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-13822.

[16] Suzanne Lacy, Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art (Seattle, Wash: Bay Press, 1995).

_____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

Featured Image: The letter. Hermann Schiefelbein. Collection of Edgar Schiefelbein.

fig. 1: Ernst Stinsoff’s house, Schiefelbein painting «Wedding of the Nations», Photo by Arthur Wischral. Collection Edgar Schiefelbein.

fig. 2: Wagons and Horses. Hermann Schiefelbein. Collection of the Paraná State College, Public Domain.

fig. 3: Reproduction, The Return of the Prodigal Son, Frithold Baumann’s collection, rights reserved by the author.

fig. 4: Schiefelbein’s grave © Michel Kobelinski.

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Kobelinski, Michel: Brasilianische Kunst und Identität durch Schiefelbein? in: Public History Weekly 9 (2021) 3, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17822.

Translated by Mark Kyburz (http://www.englishprojects.ch/)

Redaktionelle Verantwortung

Copyright © 2021 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 9 (2021) 3

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17822

Tags: Art (Kunst), Brazil (Brasilien), Iconography, Identity (Identität), Landscape, Language: Portuguese

English version below. To all our other readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

OPEN PEER REVIEW

No rastro de um paranista de Schwerte: usos públicos da arte e historiografia

Em 1926, por ocasião da inauguração do Centro Paranista o historiador Romário Martins (1974-1948) sintetizaria a essência do paranista como “todo aquele que tem pelo Paraná uma afeição sincera, e que notavelmente a demonstra em qualquer manifestação de actividade digna, útil à coletividade paranaense” [1]. Dentre essas atividades dignas, podemos identificar aquela do herói da nossa história:

Paranista é aquele que em terras do Paraná lavrou um campo, cadeou uma floresta, lançou uma ponte, construiu uma máquina, dirigiu uma fábrica, compoz uma estrophe, pintou um quadro (…).[2]

No texto que acabamos de ler, a obra de Hermann Schiefelbein (1885-1933) é apresentada como um dos importantes marcadores da identidade no Paraná, sul do Brasil, hoje. Seu reconhecimento, contudo, como não fora imediato. Sua estima flutuou ao sabor das disputas políticas em torno às mitologias que melhor representariam a região e o Brasil em sua jovem república. O texto explora o conteúdo e características estéticas de obras-chave do pintor. Uma contextualização histórica um pouco mais detida teria ajudado a compreender melhor o momento político em questão.

A indicação de que as comunidades por onde transitou o artista não conhecerem bem sua história e obra, nos dá boas pistas de que o encapusulamento do artista pelo movimento paranista não foi, necessariamente, expresso ou assimilado pelo imaginário popular, apesar de sua circulação em museus, galerias de arte e instituições governais. O texto nos leva a questionar de que forma o reconhecimento tardio do pintor está relacionado à sua condição social de imigrante, para além das impressões sobre seu trabalho e talento.

Se recuarmos um pouco no tempo, vemos que em meados do século XIX, a busca pela afirmação de um Estado “iluminado, esclarecido e civilizador” demandava uma interiorização da civilização” [3]. Ou seja, o processo civilizador da Nação brasileira precisava se realizar regionalmente. Para Manoel Luiz Salgado Guimarães, a fundação do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro (IHGB) se relacionava a este plano de “Nação como unidade homogênea e como resultado de uma interpretação orgânica entre as diversas províncias”[4].

Na virada para o século XX, os ideais de ordem e progresso passaram a integrar os esforços para forjar um tipo de nacionalismo. No Brasil, marcado pela colonização, esse processo era atravessado pela relação das pessoas com a terra. Estima-se que de 3,5 milhões de imigrantes chegaram ao Brasil durante a “grande imigração”, inclusive, Schiefelbein. A imigração acirrou os conflitos regionais. No Paraná, o texto aponta vagamente um problema relacionado à indeferimento da cidadania aos colonos e divergências com as elites. Mas as disputas locais podiam ser ainda mais extratificadas, envolvendo conflitos entre latifundiários, povos indígenas, posseiros e colonos.

Neste contexto, a referida busca pela harmonia entre os diferentes grupos étnicos e sociais – expressa na renomeação da tela “O Baile das Raças” para “Boda das Nações” – passava pela equalização desses conflitos e pela integração do imigrante. Podemos nos perguntar, se a exemplo da instrumentalização de uma escrita da história no XIX, a criação da “Festa das Colônias” e a apropriação dos quadros de Schiefelbein por um certo público através de ações do governo paranaense também não significou uma forma de integração inventada, à moda do IHGB. O texto é inspirador para pensar as relações entre historiografia, construção da nação e arte.

Para Giralda Seyferth, a teutobrasilianidade se constituiu a partir de “sentimentos de solidariedade baseado numa história comum” – um laço mais étnico que político[5]. Por outro lado, o texto trata a incorporação das mencionadas telas de Schiefelbein à identidade paranaense e à mitologia nacional como meio para a formação de uma “comunidade de sentidos” que influenciasse o imaginário popular. Trata-se, portanto, de um processo dupla-face e relacional, a contempo étnico e político, identificado graças à análise das obras de Schiefelbein em sua historicidade.

A partir de um caso específico, o autor nos convida a refletir a potente relação entre história e arte pública – frente a ser mais explorada por historiadores e demais profissionais atuantes em museus e patrimônio. Fica em aberto, de que forma a história pública, em articulação com a arte pública, pode nos trazer elucidações acerca dos usos públicos da arte e como isso pode informar a historiografia? Para o caso de Schiefelbein a chave foi interrogar seu papel na Deutschbrasilianertum em colaboração com a comunidade, através das revitalizações. Um elemento central desta contribuição que permaneceu implítico foi a consideração da cultura material (ex. o cemitério) como interface e gatilho para a colaboração. Indiretamente, o autor renova a mensagem de Raphael Samuel, nos convidando a calçar um par de botas bem robusto e ir a campo “reconhecer a configuração do terreno”, como sugeriram Marc Bloch e H. R. Tawney[6]. E, claro, falar com as pessoas!

______

[1] Martins apud Iachtechen. Ver: Iachtechen, Fabio Luciano. “Um Volksgeist Paranista: Algumas Considerações Sobre a Escrita Da História de Romário Martins.” In Anais Eletrônicos, 01–10. Ponta Grossa-PR: ANPUH PR, 2018. p.01 (grifo nosso) http://www.encontro2018.pr.anpuh.org/simposio/anaiscomplementares.

[2] Ibidem.

[3] Ver Guimarães, Manoel Luis Lima Salgado. “Nação e Civilização nos Trópicos: o Instituto Histórico Geográfico Brasileiro e o projeto de uma história nacional.” Revista Estudos Históricos 1, no. 1 (January 30, 1988): p. 10. http://bibliotecadigital.fgv.br/ojs/index.php/reh/article/view/1935.

[4] Idbem, p.17.

[5] Cf. Seyferth, Giralda. “Identidade Étnica, Assimilação e Cidadania: A Imigração Alemã e o Estado Brasileiro.” Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais 9, no. 26 (1994): p.06-07.

[6] Ver Samuel, Raphael. Theatres of Memory: Past and Present in Contemporary Culture. Verso Books, 2012. p. 499

_______________

On the trail of a paranista from Schwerte: public uses of art and historiography

In 1926, on the occasion of the inauguration of the Centro Paranista, the historian Romário Martins (1974-1948) would synthesize the essence of the Paranista as “everyone who has a sincere affection for Paraná, and who shows it notably in any manifestation of worthy activity, useful to the paranaense collectivity[1]. Among these worthy activities, we can identify that of the hero of our history:

A Paranista is the one who, in the lands of Paraná, has plowed a field, padlocked a forest, laid a bridge, built a machine, run a factory, composed a verse, painted a picture (…). [2]

In the text we have just read, Hermann Schiefelbein’s work (1885-1933) is presented as one of the relevant identity markers in Paraná, Southern Brazil, today. His recognition, however, was not immediate. Its esteem fluctuated according to the political disputes around the mythologies that would best represent the region and Brazil in its young republic. The text explores the artistic content and aesthetic characteristics of key works by the painter. A slightly more detailed historical contextualization would have helped to understand the political moment in question better.

The indication that the communities through which the artist passed were not well acquainted with his history and pictures gives us good clues that the encapsulation of the artist by the Paranista movement was not necessarily expressed or assimilated by people’s imagination, despite his paintings circulation in museums, art galleries and governmental institutions. The text leads us to question how the painter’s late recognition is related to his social condition as an immigrant, beyond the impressions about his work and talent.

If we go back a little in time, we see that in the middle of the 19th century, the search for the affirmation of an “enlightened, educated and civilized” State demanded an internalization of civilization[3]. In other words, the civilizing process of the Brazilian Nation needed to take place regionally too. For Manoel Luiz Salgado Guimarães, the foundation of the Brazilian Historical and Geographical Institute (IHGB) was related to this plan of “Nation as a homogeneous unit and as the result of an organic interpretation among the several provinces” [4].

At the turn of the 20th century, the ideals of order and progress became part of the efforts to forge a type of nationalism. In Brazil, marked by colonization, this process was traversed by people’s relationship with the land. It is estimated that 3.5 million immigrants arrived in Brazil during the “great immigration”, including Schiefelbein. Immigration exacerbated regional conflicts. Regarding Paraná, the text vaguely points to a problem related to the denial of citizenship to the settlers and disagreements with the elites. However, local disputes could be even more layered, involving conflicts between landowners, indigenous peoples, squatters and settlers.

In this context, the referred search for harmony among different ethnic and social groups – expressed in the renaming of the painting “Dance of the Races” to “Wedding of the Nations” – passed through these conflicts’ equalization and the integration of the immigrant. We can ask ourselves if the creation of the “Festa das Colônias” and the appropriation of Schiefelbein’s paintings by a certain public through Paraná’s government’s actions did not mean an invented form of integration, in the model of IHGB. The text is inspiring for thinking about the relationships between historiography, nation-building, and art.

For Giralda Seyferth, the Deutschbrasilianertum was constituted from “feelings of solidarity based on a common history” – a more ethnic than political bond[5]. On the other hand, the text discusses the incorporation of Schiefelbein’s paintings into the Paranaense identity and national mythology as a means for the formation of a “community of meanings” that influenced the people’s imagination. It is, therefore, a double-sided and relational process, at the same time ethnic and political, identified thanks to the analysis of Schiefelbein’s works in their historicity.

From a specific case, the author invites us to reflect on the powerful relationship between history and public art – a front to be further explored by historians and other professionals working in museums and heritage. However, it remains open in what way public history, in articulation with public art, can bring us elucidations about the public uses of art and how this can inform historiography? For Schiefelbein’s case, the key was to interrogate his role in Deutschbrasilianertum in collaboration with the community through revitalizations. A central element of this contribution that remained implicit was the consideration of material culture (e.g. the cemetery) as an interface and trigger for collaboration. Indirectly, the author renews Raphael Samuel’s message by inviting us to put on a stout pair of boots and go into the field to “learn the lie of the land,” as Marc Bloch and H. R. Tawney suggested[6] . And, of course, talk to the people!

_____

[1] Martins apud Iachtechen. See: . “Um Volksgeist Paranista: Algumas Considerações Sobre a Escrita Da História de Romário Martins.” In Anais Eletrônicos, 01–10. Ponta Grossa-PR: ANPUH PR, 2018. p.01 (author’s highlight) http://www.encontro2018.pr.anpuh.org/simposio/anaiscomplementares.

[2] Ibid.

[3] See Guimarães, Manoel Luis Lima Salgado. “Nação e Civilização nos Trópicos: o Instituto Histórico Geográfico Brasileiro e o projeto de uma história nacional.” Revista Estudos Históricos 1, no. 1 (January 30, 1988): p. 10. http://bibliotecadigital.fgv.br/ojs/index.php/reh/article/view/1935.

[4] Idbem, p.17.

[5] Cf. Seyferth, Giralda. “Identidade Étnica, Assimilação e Cidadania: A Imigração Alemã e o Estado Brasileiro.” Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais 9, no. 26 (1994): p.06-07.

[6] Ver Samuel, Raphael. Theatres of Memory: Past and Present in Contemporary Culture. Verso Books, 2012. p. 499

To all our non-Portuguese speaking readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

Author’s Reply: Obscuridades artísticas, literárias e historiográficas

As questões de Anita Lucchesi são úteis para pensar nos pontos obscuros de nosso texto e as relações entre os usos públicos da arte e as narrativas históricas. Neste sentido, constata-se que as obras de Schiefelbein foram usadas para reforçar a pedagogia visual do Paranismo e, ao mesmo tempo, consolidar uma narrativa histórica herdeira da historiografia paulista.

A regionalização do processo civilizador partiu dos ideais construídos pelos historiadores Pedro Taques de Almeida Pais Leme, Frei Gaspar da Madre de Deus [século XVIII] e pelo Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro – IHGB [século XIX].[1] Nesta mitologia exalta-se o amor pela terra natal, o heroísmo e o progresso.[2] O sentimento ufanista, presente nos dias atuais na ideia do Brasil como o reino da natureza e da hospitalidade, é uma construção histórica associada às paixões políticas.[3] Por este motivo, deve-se considerar outras versões da história do Brasil e o desencanto político com a figura do herói, tanto pela perda de valores e abandono de ideais quanto pela corrupção do caráter. A história brasileira foi marcada pela evangelização forçada, pela devastação florestal, pelo massacre de populações indígenas, pelo latifúndio e pela escravidão.[4]

Para Carneiro os imigrantes são os heróis civilizadores dos sertões paranaenses.[5] No entanto, o romance histórico “Pioneiros do Iguatemi”, de Fernandes se distancia desta mitologia ao representar a figura do herói romântico (Júlio Estêvão) que luta pelo amor da índia Nyaca e conta a opressão de portugueses e espanhóis.[6] Assim, a ficção histórica, discute o problema real da integração étnica e social de imigrantes, indígenas e afrodescendentes na história do Estado do Paraná.

Entre os motivos para a obscuridade de Schiefelbein estão os efeitos danosos das políticas repressivas da Era Vargas (1930-1945), que suprimiam o ensino de línguas e a difusão da arte estrangeira. Estas políticas atingiram diretamente as comunidades e a instituições de origem alemã na região onde o artista viveu. Entre elas, o Colégio Teuto-Brasileiro da Comunidade Luterana do Brasil, a Paróquia Santa Rosa de Lima e a Escola de Estrangeiros, em Porto União (SC).

As obras de Schiefelbein não retratam diretamente uma história sangrenta, isto é, a I Guerra Mundial e a Guerra do Contestado. As referências religiosas em seu túmulo e alguns de seus quadros levantam pistas importantes sobre sua condição de imigrante e sobre os conflitos sociais. O quadro “Jó e seus amigos” (1927) infere nos lamentos sobre o nascimento e o pecado, o desejo da morte e o consolo dos amigos, além da relação entre o sensível e o racional. Portanto, a composição artística sugere os imigrantes alemães como párias em terras estranhas e seu sofrimento para se adaptar à realidade brasileira. A representação dos aspectos práticos da vida associa arte e religiosidade. A tela “João Maria”, por exemplo, que tematiza a pregação de um monge para sertanejos também abre espaço para a religiosidade popular entre os brasileiros e reflete indiretamente a Guerra do Contestado.[7] Na interação com a comunidade de descendentes alemães em Porto Vitória também foi possível identificar ligações históricas entre famílias, as quais serviram como gatilho para a colaboração com o nosso trabalho. É claro, imaginamos a possibilidade do estudo das relações de amizade naquela comunidade.[8]

As articulações entre história pública e Arte Pública nos faz refletir sobre as experiências sensíveis, cognitivas e estéticas. Precisamos levar em conta os sentidos de comunidade e de colaboração, aspectos que envolvem escutas sensíveis, particularmente aquelas relacionadas à história local. Neste sentido, os historiadores devem promover o aquilo que Hilda Kean chamou de engajamento participativo para compreendemos o passado e seus usos.[9]

_________________________________

[1] Ver Kobelinski, M. “A negação e a exaltação dos sertanistas de São Paulo nos discursos dos padres Pierre-François-Xavier de Charlevoix, D. José Vaissette e Gaspar da Madre de Deus (1756-1774)”. História da Historiografia, v. 2, p. 49-69, 2012.

[2] Celso, Affonso de A. F. “Por que me ufano do meu país: right or wrong, my country”. Rio de Janeiro: F. Briguiet & Cia., 1943.

[3] ANSART, Pierre. “La gestion des passions politiques”. Lousane: L’age d’Homme”, 1983.

[4] Meyer, Marlyse. “Caminhos do imaginário no Brasil”. São Paulo, Edusp, 1993.

[5] Carneiro, David. “História Psicológica do Paraná”. Curitiba: Tip. João Haupt, 1944.

[6] Fernandes, Helle Vellozo. “Pioneiros do Iguatemi”. Curitiba: Imprensa da UFPR, 1966.

[7]A Guerra do Contestado (1912-1916) foi um conflito complexo entre a população sertaneja, os governos estadual e federal. As disputas envolveram a posse da terra, a apropriação de recursos naturais, instalação de rede ferroviária, conflitos territoriais entre os estados do Paraná e de Santa Catarina, a presença de líderes messiânicos (João Maria), revoltas entre sertanejos, caboclos e madeireiros, áreas de concessão governamental e instalação de companhias estrangeiras, como por exemplo, a Southern Brazil Lumber & Colonization.

[8] Vicent-Buffault, Anne. “Da amizade: uma história do exercício da amizade nos séculos XVIII e XIX”. São Paulo: Zahar, 1996. [Anne Vincent-Buffault, L’exercice de l’amitié. “Pour une histoire des pratiques amicales aux xviue et xixe siècles”. Paris, Le Seuil, 1995.]

[9] Kean, Hilda, Martin, Paul. “The Public History Reader”. London/New York: Routledge, 2013.