Abstract:

Felicitas Macgilchrist’s contribution is about the question of what happens to content and historical knowledge when the materiality or mediality of school history textbooks changes over time. Her observation is that school history textbooks are “elastic”, they hold different fields together like a rubber band. The particular focus is on the connection between school history textbooks and the representation of national history.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17609

Languages: English, German

History textbooks have always been changing. From textual narratives in the nineteenth century to the late twentieth century’s books filled with images, source documents and tasks. Now, in our postdigital twenty-first century, textbooks are moving online as apps and websites. But what happens to the content as textbooks’ materiality changes? I suggest here that textbooks are “elastic”. Like an elastic band, they pull the national(ist) past, which was once the reason to institutionalise history education, with them. First, textbooks pull on the curriculum. Second, textbooks pull linearity with them. Third, textbooks pull on monovocality. The piece concludes by noting some augmentations which may reshape the elastic band of national(ist) history.

Old Distinctions

History textbooks are elastic: they pull the past with them into the postdigital age, and this past is often a national or nationalist past. With postdigital, I am referring to the ways in which the digital and the physical/analogue/printed are interwoven in our daily lives.[1] The old distinctions between online and offline, real life and virtual life no longer make much sense. Even the most apparently unconnected people, who own no smartphones or computers, are connected to a global network of digital traces as soon as they have, for instance, a bank account.[2] The digital is no longer new; disruption is no longer surprising; digital technology is woven into the messiness of everyday life, sometimes as an unproblematic background, sometimes as a sharply felt lack, sometimes as an infuriating or joyful foreground.

For textbooks, this means the old distinctions between a “textbook”, thought of as a printed book, and “online materials”, “digital educational media” or “educational software” also cease to make sense. Today’s history textbooks are often printed books, hardcover in some countries, like glossy magazines in other countries. But today’s history textbooks are just as likely to be online PDFs, born digital e-books or interactive software packages. These digital textbooks are “text-“, with words and images, and they are “-books”, with electronically ordered chapters.

Elastic Textbooks

But what happens to the politics of historical knowledge as textbooks’ materiality changes? I suggest here that textbooks are “elastic”. Like an elastic band, stretching from today into the past, they pull the past into our postdigital world. Putting this metaphor of the elastic band to work highlights three ways that today’s print/digital textbooks pull traditional knowledge practices into our lives.

First, textbooks pull on the curriculum: The classic function of a textbook is to fill the curriculum of a single school subject with materials for teaching and learning. Authors turn short history curricula into lengthy textbooks. Despite curricular shifts from, e.g., an input to an output orientation, history curricula around the world remain deeply embedded in national narratives. National identity, nation building, national(ism) were among the prime motivations to institutionalise history education for all schoolchildren.[3] Stories of colonies and colonisers; stories of social and technological progress; stories of conflicts, wars and peace treaties. Even when these stories are embedded in global processes or local contexts, they continue to focus on the nation. As long as there are individual school subjects like history, there will be curricula for these individual subjects. And we will have elastic history textbooks which reproduce national history.

Second, textbooks pull linearity with them: Books with sections, chapters, headings and sub-headings invite us to read them in a linear fashion. Page 1 is followed by page 2. Authors struggle to fit complex, entangled histories – which contest the centrality of the nation – into the linear chapter structure. At the same time, databases arguably stand at the core of digital technology. Databases categorise in particular ways, and enable connections, layers and searches which are not possible with textbooks (yet).[4] Stories of linear progress in specific nations still – sometimes inadvertently, and despite textbook interventions such as the Schools History Project – dominate much history teaching. Students rework textbooks into causal narratives.[5] As long as history is primarily presented in textbooks through chapters, to be taught one step at a time, we will have elastic textbooks which reproduce nationally-situated linear narratives.

Third, textbooks pull on monovocality: In many parts of the world, authors and textbook developers aim to include multiple perspectives. Yet the perspectives included are often from diverse privileged voices, rather than radically different voices from agonistic societal positions.[6] Unlike printed textbooks, digital textbooks are not limited by space (they will not become too heavy). They do not need to use an age-appropriate font size (since users can zoom in and out) nor a maximum number of words per page (users can scroll up and down). Where printed textbooks include, for instance, two historical source documents, digital textbooks could include 20 or more documents, and ask students to swipe through them to select two to read. However, as long as we have limited selections of whose perspective is included, we will have elastic textbooks that reproduce dominant historical narratives.

Reshaping the Elastic Band

Can different forms of materiality pull apart the elastic band or rework it into novel shapes? One way may be to augment textbooks. Responding to the problem that only 11% of the stories US history textbooks are about women, Daughters of the Evolution produced “Lessons in Herstory”, an augmented reality (AR) app.[7] Users hold their smartphone over history textbook images of a powerful man and the app shows related history about a powerful woman. AR could ease the path to, for instance, using today’s textbooks for Lessons in Entangled History or Lessons in Decolonial History.

Games are often lauded for their motivational effects, their power to engage students’ emotions, or the difference it makes in a history classroom when students play computer games instead of working with texts. But perhaps a key reason for teaching and learning with games is to reshape the elastic band, by dissociating traditional knowledge practices and reassociating other knowledge practices in history education.[8]

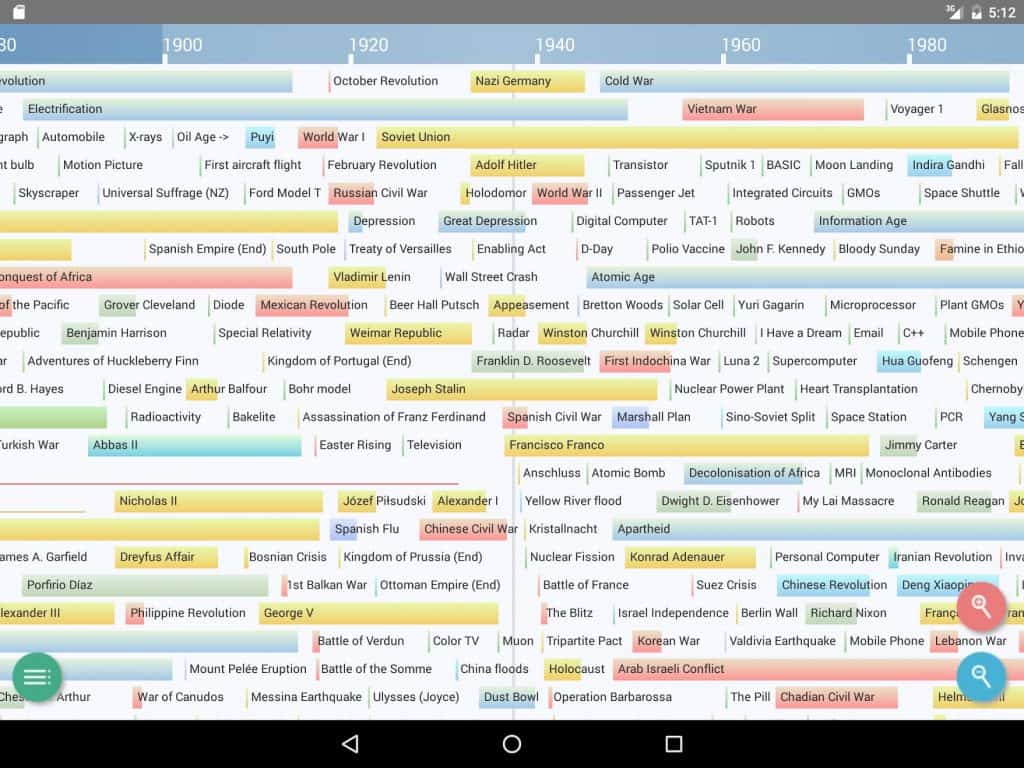

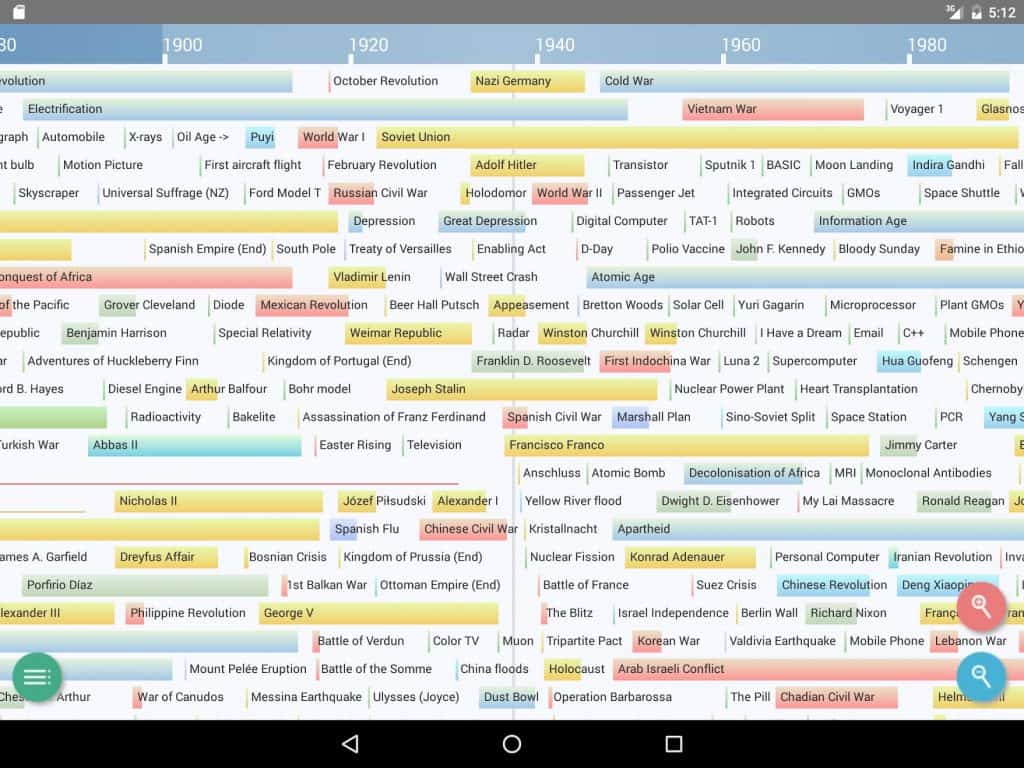

Similarly, apps offering a data overload, such as “History Timeline”, show multiple entries for world history and thereby entangle the histories of science, art, literature, nations, leaders, wars, philosophy and music.[9] Integrating this sort of data I imagine the next step for history textbooks. The “text-” remains text and the “-book” is still a book, but more akin to Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves than a regular chapter-structured book.[10]

Indeterminate Effects

I have argued here that the materiality of textbooks – whether printed or digital – invites an elastic connection to the national(ist) past of teaching history. I am not suggesting that authors or developers intend this. Despite their valiant attempts to change the ways textbooks make history available to students, whether by including postcolonial reflections or orienting to competences, the materiality of the elastic band has its own agency. Similarly, AR or networked technologies might break or reshape the elastic band, but they might only stretch it further.

Ethnographic research on students’ use of textbooks, however, has shown quite clearly that their interpretations invariably exceed authors’ or developers’ expectations. Sometimes they make national narratives out of decolonial texts; other times they critically deconstruct the most national of textbook materials.[11] While trying to avoid making students into the innocent heroes of classroom practices, this research has observed how students are constantly working at the elastic band, in multiple, contradictory and innovative ways.[12] I look forward to seeing what they make of AR or entangled timelines.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Ahlrichs, Johanna. Die Relevanz des Beiläufigen. Alltägliche Praktiken im Geschichtsunterricht und ihre politischen Implikationen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2020.

- Fuchs, Eckhardt and Annekatrin Bock. Palgrave Handbook of Textbook Studies. London: Palgrave, 2018.

- Bowker, Geoffrey C. Memory Practices in the Sciences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006.

Web Resources

- Christophe, Barbara: Historisch Denken mit digitalen Spielen http://basement.gei.de/index.php/2021/03/04/historisch-denken-mit-digitalen-spielen (last accessed 3 March 2021).

- Augmented Reality App: https://www.lessonsinherstory.com (last accessed 3 March 2021).

_____________________

[1] Petar Jandrić et al., “Postdigital Dialogue,” Postdigital Science and Education 1, no. 1 (2019): 163-189. Available here https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-018-0011-x. For a similar view of our current condition, see also Felix Stalder, Kultur der Digitalität (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2015); in English: Felix Stalder, The Digital Condition (London: Polity, 2018).

[2] Paul Baker, Jarice Hanson, and Jeremy Hunsinger, eds., The Unconnected: Social Justice, Participation, and Engagement in the Information Society (New York: Peter Lang, 2013).

[3] Eckhardt Fuchs and Annekatrin Bock, Palgrave Handbook of Textbook Studies (London: Palgrave, 2018).

[4] On databases, see Geoffrey C. Bowker, Memory Practices in the Sciences (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006).

[5] On the materiality of how textbook use (inadvertently) enacts linear time, see Johanna Ahlrichs, Die Relevanz des Beiläufigen. Alltägliche Praktiken im Geschichtsunterricht und ihre politischen Implikationen (Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2020).

[6] Barbara Christophe and Maren Tribukait, Learning to Disagree: Needs Assessment (Eckert.Dossiers 5.2019), https://repository.gei.de/handle/11428/305; Martin Lücke, “Multiperspektivität, Kontroversität, Pluralität,” in Handbuch Praxis des Geschichtsunterrichts, ed. Michele Barricelli and Martin Lücke (Schwalbach/Ts: Wochenschau, 2012), 281-288.

[7] See https://www.lessonsinherstory.com (last accessed 3 March 2021).

[8] See, for instance, Through the Darkest of Times (https://paintbucket.de/en/ttdot), When We Disappear (https://www.inlusio.com/whenwedisappear) or Attentat 1942! (http://attentat1942.com). See also Barbara Christophe, Historisch Denken mit digitalen Spielen http://basement.gei.de/index.php/2021/03/04/historisch-denken-mit-digitalen-spielen (last accessed 3 March 2021).

[9] History Timeline is only available for Android, see https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.timleg.historytimeline (last accessed 3 March 2021).

[10] Mark Z. Danielewski, House of Leaves (New York: Pantheon Books, 2000).

[11] In our research, for instance, Felicitas Macgilchrist et al., “Memory practices and colonial discourse: Tracing text trajectories and lines of flight,” Critical Discourse Studies 14, no. 4 (2017): 341-361 http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17405904.2017.1325382. See also Patrick Mielke, Die Aushandlung von Zugehörigkeit und Differenz im Geschichtsunterricht. Eine ethnographische Diskursanalyse (University of Goettingen, 2020); Annekatrin Bock and Felicitas Macgilchrist, “‘Born digital‘-Schulbücher in der empirischen Forschung – Fragen, Forschungsdesign, erste Erkenntnisse,” ed. Florian Sochatzy and Marcus Ventzke, Bildung digital gestalten (Eichstätt, 2020). Available here https://bildung-digital-gestalten.institut-fuer-digitales-lernen.de/inhalt/empirische-forschung. For more on indeterminate and unruly ways of doing history education with various media, see Maren Tribukait and Felicitas Macgilchrist, Historical Encounters: Special Issue on the Politics of Doing History Education 7, no. 2 (2020). Available here http://hej.hermes-history.net/index.php/HEJ/article/view/167 (last accessed 3 March 2021).

[12] For a critical reflection on presuming students to be innocent, see Lisa Farley, “Innocence,” in Trickbox of Memory: Essays on Power and Disorderly Pasts, ed. Felicitas Macgilchrist and Rosalie Metro (Earth, Milky Way: punctum books, 2020). Available here: https://punctumbooks.com/titles/trickbox-of-memory-essays-on-power-and-disorderly-pasts (last accessed 3 March 2021).

_____________________

Image Credits

Bind Colors © Pierre Stickney CC-0.

Recommended Citation

Macgilchrist, Felicitas: Elastic Textbooks: Pulling National Pasts Forward. In: Public History Weekly 9 (2021) 2, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17609.

Editorial Responsibility

Christian Bunnenberg / Lukas Tobler / Peter Gautschi (Team Lucerne)

Geschichtslehrbücher haben sich schon immer verändert, von den Erzählungen in Textform des 19. Jahrhunderts bis zu den Büchern des späten 20. Jahrhunderts mit Bildern, Quellendokumenten und Aufgaben. Jetzt, in unserem postdigitalen 21. Jahrhundert, verschieben sich die Lehrbücher als Apps und Websites auf Online-Plattformen. Doch was geschieht mit den Inhalten, wenn sich Lehrbücher stofflich verändern? Ich bin diesbezüglich der Ansicht, dass Lehrbücher “elastisch” sind. Wie ein Gummiband ziehen sie die national(istisch)e Vergangenheit, die ehemals der Grund zur Institutionalisierung des Geschichtsunterrichts war, mit sich. Zuerst einmal ziehen die Schullehrbücher am Lehrplan. Zweitens ziehen die Lehrbücher die Linearität mit sich. Und drittens ziehen die Lehrbücher an der Monovokalität. Der Beitrag schließt mit Überlegungen zu Erweiterungen, die das Gummiband der national(istisch)en Geschichte lösen könnten.

Frühere Unterschiede

Geschichtslehrbücher sind elastisch: Sie ziehen die Vergangenheit mit sich ins postdigitale Zeitalter, und diese Vergangenheit ist oft eine nationale oder nationalistische Vergangenheit. Mit postdigital beziehe ich mich auf die Art und Weise, wie das Digitale und Physische/Analoge/Gedruckte mit unserem täglichen Leben verwoben ist.[1] Die früheren Unterschiede zwischen online und offline, wirklichem Leben und virtuellem Leben machen keinen Sinn mehr. Selbst die scheinbar digital nicht vernetzten Menschen, welche keine Smartphones und Computer besitzen, sind mit einem globalen Netzwerk von digitalen Datenflüssen verbunden, sobald sie, zum Beispiel, über ein Bankkonto verfügen.[2] Das Digitale ist nicht neu; Störungen kommen nicht mehr als Überraschung; digitale Technologie geht einher mit dem hektisch-chaotischen Alltagsleben, manchmal als unproblematischer Hintergrund, manchmal als stark empfundener Mangel, manchmal als wütend oder freudig wahrgenommener Vordergrund.

In Bezug auf Lehrbücher heisst dies, dass die alten Unterschiede zwischen einem “Lehrbuch”, in der Form des gedruckten Buches, von “Online-Materialen”, “digitalen Unterrichtsmedien” oder “Unterrichtssoftware” auch immer weniger Sinn machen. Die heutigen Geschichtslehrbücher erscheinen oft als gedruckte Ausgaben, in einigen Ländern in gebundener Buchform, wie auch als Hochglanzmagazine in anderen Ländern. Aber die Geschichtslehrbücher von heute kommen ebenso als Online-PDFs daher, hervorgegangen aus digitalen E-Books oder interaktiven Softwarepaketen. Diese digitalen Lehrbücher verkörpern eine “Lehre” mit Worten und Bildern, aber auch “Bücher” mit elektronisch strukturierten Kapiteln.

Elastische Lehrbücher

Aber was geschieht mit der Politik des historischen Wissens, wenn sich die Materialität der Lehrbücher verändert? Diesbezüglich denke ich, dass Lehrbücher “elastisch” sind. Wie ein Gummiband, das sich vom Heute in die Vergangenheit spannt, ziehen diese die Vergangenheit in unsere postdigitale Welt. Wenn man die Metapher des Gummibandes verwendet, werden drei Möglichkeiten deutlich, wie die heutigen gedruckten bzw. digitalen Lehrbücher traditionelle Wissenspraktiken in unsere Lebenswelten hineinziehen. Erstens ziehen Lehrbücher am Lehrplan: Die klassische Funktion eines Lehrbuchs ist es, den Lehrplan eines einzelnen Schulfachs mit Materialien zum Lehren und Lernen zu füllen. Die Autor:innen machen aus Geschichtslehrplänen ausführliche Lehrbücher. Trotz curricularer Verschiebungen, zum Beispiel von einer Input- zu einer Output-Orientierung, bleiben Geschichtslehrpläne auf der ganzen Welt tief in nationale Narrative eingebettet. Nationale Identität, Nationsbildung, National(ismus) gehörten zu den Hauptmotivationen, den Geschichtsunterricht für alle Schulkinder zu institutionalisieren.[3] Geschichten von Kolonien und Kolonisatoren, Geschichten von sozialem und technischem Fortschritt, Geschichten von Konflikten, Kriegen und Friedensverträgen – selbst wenn diese Geschichten in globale Prozesse oder lokale Kontexte eingebettet sind, fokussieren sie sich weiterhin auf die Nation. Solange es einzelne Schulfächer wie Geschichte gibt, wird es auch Lehrpläne für diese einzelnen Fächer geben. Und wir werden elastische Geschichtslehrbücher haben, welche die nationale Geschichte wiedergeben.

Zweitens ziehen Lehrbücher Linearität mit sich: Bücher mit Abschnitten, Kapiteln, Titeln und Untertiteln laden uns dazu ein, sie auf lineare Weise zu lesen. Auf Seite 1 folgt Seite 2. Die Autor:innen geben sich Mühe, komplexe, verwickelte Geschichten – welche die Zentralität der Nation in Frage stellen – in die lineare Kapitelstruktur hineinzupassen. Gleichzeitig stehen Datenbanken aktuell im Zentrum der digitalen Technologie. Datenbanken kategorisieren in besonderer Weise und ermöglichen Verknüpfungen, Ebenen und Recherchen, die mit Lehrbüchern (noch) nicht möglich sind.[4] Geschichten von linearem Fortschritt in den spezifischen Nationen dominieren immer noch – manchmal ungewollt und trotz Schulbuchmassnahmen wie dem Schools History Project – einen Großteil des Geschichtsunterrichts. Schüler:innen arbeiten Lehrbücher zu kausalen Narrativen um.[5] Solange Geschichte in Lehrbüchern primär kapitelweise dargestellt wird, um Schritt für Schritt unterrichtet zu werden, werden wir elastische Lehrbücher haben, die national verortete lineare Narrative reproduzieren.

Drittens ziehen die Lehrbücher an der Monovokalität: In vielen Teilen der Welt sind Autor:innen und Lehrbuchentwickler:innen darum bestrebt, vielfache Perspektiven einzubeziehen. Dennoch stammen die einbezogenen Perspektiven eher von diversen privilegierten Stimmen als von radikal anderen Stimmen aus agonistischen gesellschaftlichen Positionen.[6] Im Gegensatz zu gedruckten Lehrbüchern sind digitale Lehrbücher nicht durch den Platz begrenzt (sie werden nicht zu schwer). Sie müssen weder eine altersgerechte Schriftgröße verwenden (da Nutzer:innen ran- und wegzoomen können) noch eine maximale Anzahl von Wörtern pro Seite (Nutzer:innen können nach oben und unten scrollen). Wo gedruckte Lehrbücher zum Beispiel zwei historische Quellendokumente enthalten, wäre es digitalen Lehrbüchern möglich, 20 oder mehr Dokumente zu präsentieren und die Schüler:innen dazu aufzufordern, diese zu überfliegen, um zwei davon zum Lesen auszuwählen. Solange wir jedoch nur eine begrenzte Auswahl von Perspektiven haben, die mit einbezogen werden können, werden wir elastische Lehrbücher haben, welche dominante historische Narrative reproduzieren.

Das Gummiband umgestalten

Können verschiedene Arten der Materialität das Gummiband auseinanderziehen oder in neue Formen umarbeiten? Eine Möglichkeit könnte darin bestehen, die Lehrbücher computergestützt zu erweitern. Als Reaktion auf das Problem, dass nur 11 Prozent der Abhandlungen in US-Geschichtslehrbüchern von Frauen handeln, produzierte Daughters of the Evolution die Augmented-Reality (AR)-App “Lessons in Herstory“.[7] Nutzer:innen halten ihr Smartphone über die Geschichtslehrbuchbilder eines “großen” Mannes und die App zeigt ein Bild, das ein entsprechendes historisches Ereignis über eine “große” Frau darstellt. AR könnte den Weg ebnen, um zum Beispiel die heutigen Schulbücher für den Unterricht über “Entangled History” (Verflechtungsgeschichte) oder zu dekolonialer Geschichte zu nutzen.

Spiele werden oft für ihre motivierende Wirkung gelobt, für ihre Fähigkeit, die Emotionen der Schüler:innen anzusprechen; oder für den Unterschied, den es in einem Geschichtsunterricht macht, wenn die Schüler:innen Computerspiele spielen, anstatt mit Texten zu arbeiten. Aber vielleicht ist ein Hauptgrund für das Lehren und Lernen mit Spielen, das Gummiband neu zu gestalten, indem traditionelle Wissenspraktiken dissoziiert und andere Wissenspraktiken im Geschichtsunterricht neu assoziiert werden.[8]

Ebenso zeigen Apps, wie zum Beispiel “History Timeline“, eine Vielzahl an weltgeschichtlicher Einträge und verschränken damit die Geschichte von Wissenschaft, Kunst, Literatur, Nationen, Führern, Kriegen, Philosophie und Musik.[9] Diese Art von Daten zu integrieren, denke ich, ist der nächste Schritt für Geschichtslehrbücher. Die “Lehre” bleibt Lehre und das “Buch” ist immer noch ein Buch, aber eher an Mark Z. Danielewskis “House of Leaves” angelehnt als an ein handelsübliches Buch mit Kapitelstruktur.[10]

Unbestimmte Wirkung(en)

Ich habe an dieser Stelle argumentiert, dass die Materialität von Schulbüchern – ob gedruckt oder digital – zu einer elastischen Verknüpfung mit der national(istisch)en Vergangenheit des Geschichtsunterrichts einlädt. Ich bin nicht der Meinung, dass die Autor:innen oder Entwickler:innen dies beabsichtigen. Trotz der beherzten Versuche, die Art und Weise, wie Lehrbücher Geschichte für Schüler:innen zugänglich machen, zu verändern, sei es durch die Einbeziehung postkolonialer Reflexionen oder die Ausrichtung auf Kompetenzen, hat die Materialität des Gummibandes ihre eigene Wirkung. Gleichermassen könnte es sein, dass AR- oder vernetzte Technologien das Gummiband zerreissen, umgestalten oder aber es auch nur weiter ausdehnen.

Ethnographische Forschung zur Nutzung von Lehrbüchern durch Schüler:innen haben jedoch ziemlich klar gezeigt, dass ihre Interpretationen durchwegs die Autor:innen oder Entwickler:innen überraschen. Zuweilen machen sie aus dekolonialen Texten nationale Narrative; in anderen Fällen dekonstruieren sie kritisch die nationalsten aller Lehrbuchmaterialien.[11] Während versucht wird zu vermeiden, Schüler:innen zu unschuldigen Held:innen von Unterrichtspraktiken zu machen, hat diese Forschung die Beobachtung gemacht, dass Schüler:innen ständig am Gummiband arbeiten, auf vielfältige, widersprüchliche und innovative Weise.[12] Ich freue mich darauf zu sehen, was sie aus AR oder verflochtenen Zeitachsen machen.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Ahlrichs, Johanna. Die Relevanz des Beiläufigen. Alltägliche Praktiken im Geschichtsunterricht und ihre politischen Implikationen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2020.

- Fuchs, Eckhardt and Annekatrin Bock. Palgrave Handbook of Textbook Studies. London: Palgrave, 2018.

- Bowker, Geoffrey C. Memory Practices in the Sciences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006.

Webressourcen

- Christophe, Barbara: Historisch Denken mit digitalen Spielen http://basement.gei.de/index.php/2021/03/04/historisch-denken-mit-digitalen-spielen (letzter Zugriff 3. März 2021).

- Augmented Reality App: https://www.lessonsinherstory.com (letzter Zugriff 3. März 2021).

_____________________

[1] Petar Jandrić et al., “Postdigital Dialogue,” Postdigital Science and Education 1, no. 1 (2019): 163-189, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-018-0011-x. Für einen ähnlichen Überblick der aktuellen Situation, siehe auch Felix Stalder, Kultur der Digitalität (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2015); in English: Felix Stalder, The Digital Condition (London: Polity, 2018).

[2] Paul Baker, Jarice Hanson, and Jeremy Hunsinger, eds., The Unconnected: Social Justice, Participation, and Engagement in the Information Society (New York: Peter Lang, 2013).

[3] Eckhardt Fuchs and Annekatrin Bock, Palgrave Handbook of Textbook Studies (London: Palgrave, 2018).

[4] Zu Datenbanken, siehe Geoffrey C. Bowker, Memory Practices in the Sciences (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006).

[5] Zur Materialität in Bezug auf wie die (ungewollten) Nutzung von Schulbüchern die lineare Zeitachse umsetzt, siehe Johanna Ahlrichs, Die Relevanz des Beiläufigen. Alltägliche Praktiken im Geschichtsunterricht und ihre politischen Implikationen (Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2020).

[6] Barbara Christophe and Maren Tribukait, Learning to Disagree: Needs Assessment (Eckert.Dossiers 5.2019), https://repository.gei.de/handle/11428/305; Martin Lücke, “Multiperspektivität, Kontroversität, Pluralität,” in Handbuch Praxis des Geschichtsunterrichts, ed. Michele Barricelli and Martin Lücke (Schwalbach/Ts: Wochenschau, 2012), 281-288.

[7] https://www.lessonsinherstory.com (letzter Zugriff 3. März 2021).

[8] Bspw. Through the Darkest of Times (https://paintbucket.de/en/ttdot), When We Disappear (https://www.inlusio.com/whenwedisappear) or Attentat 1942! (http://attentat1942.com). See also Barbara Christophe, Historisch Denken mit digitalen Spielen http://basement.gei.de/index.php/2021/03/04/historisch-denken-mit-digitalen-spielen (letzter Zugriff 3. März 2021).

[9] History Timeline ist nur auf Android verfügbar, siehe https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.timleg.historytimeline (letzter Zugriff 3. März 2021).

[10] Mark Z. Danielewski, House of Leaves (New York: Pantheon Books, 2000).

[11] In unserer Forschung, beispielsweise, Felicitas Macgilchrist et al., “Memory practices and colonial discourse: Tracing text trajectories and lines of flight,” Critical Discourse Studies 14, no. 4 (2017): 341-361 http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17405904.2017.1325382. Siehe auch Patrick Mielke, Die Aushandlung von Zugehörigkeit und Differenz im Geschichtsunterricht. Eine ethnographische Diskursanalyse (University of Goettingen, 2020); Annekatrin Bock and Felicitas Macgilchrist, “‘Born digital‘-Schulbücher in der empirischen Forschung – Fragen, Forschungsdesign, erste Erkenntnisse,” ed. Florian Sochatzy and Marcus Ventzke, Bildung digital gestalten (Eichstätt, 2020). https://bildung-digital-gestalten.institut-fuer-digitales-lernen.de/inhalt/empirische-forschung. For more on indeterminate and unruly ways of doing history education with various media, see Maren Tribukait and Felicitas Macgilchrist, Historical Encounters: Special Issue on the Politics of Doing History Education 7, no. 2 (2020). Available here http://hej.hermes-history.net/index.php/HEJ/article/view/167 (letzter Zugriff 3. März 2021).

[12] Für eine kritische Betrachtung zur Annahme, dass Schüler unschuldig sind, siehe Lisa Farley, “Innocence,” in Trickbox of Memory: Essays on Power and Disorderly Pasts, ed. Felicitas Macgilchrist and Rosalie Metro (Earth, Milky Way: punctum books, 2020). Available here: https://punctumbooks.com/titles/trickbox-of-memory-essays-on-power-and-disorderly-pasts (letzter Zugriff 3. März 2021).

_____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

Bind Colors © Pierre Stickney CC-0.

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Macgilchrist, Felicitas: Elastische Lehrbücher: Von mitgezogenen Vergangenheit(en). In: Public History Weekly 9 (2021) 2, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17609.

Redaktionelle Verantwortung

Christian Bunnenberg / Lukas Tobler / Peter Gautschi (Team Lucerne)

Copyright (c) 2020 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 9 (2021) 2

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17609

Tags: Augmented Reality (AR), Digital Change (Digitaler Wandel), National History (Nationalgeschichte), National Narrative (Nationales Narrativ), Textbook (Schulbuch)

For a German translation see below.

OPEN PEER REVIEW

Discursive Nodes

Textbooks, the author writes, pull narratives of the past into the present because they follow the long-term logics of knowledge production that shape new accounts into the mould of old patterns. The author is critical of this tradition and highlights persisting, agreeably harmful narratives that would most probably be rejected by many textbook authors today: nationalist, colonial, homogenizing historical narratives regarding race, gender, class, and other power categories. S/he argues that, even if textbook authors are critical of such narratives, the material-discursive circumstances are so dominant that they reproduce them anyway.

When I argued lately that textbooks are discursive nodes, I thought of textbooks as entanglements. I conceptualized them as social occasions and material objects which are the condensed product of interlacing discursive threads and practices regarding specific topics and educational intentions.[1] Methodologically-metaphorically, I outlined a broad array of threads that are mingling in complex, not always intelligible ways. Each thread represents one stakeholder who contributes to textbook production: individuals, communities of knowledge, institutions, all the discursive agents with regard to one textbook. Due to the diversity of the threads their combination produces knowledge that sounds true to specific communities at a specific time and place.[2] The metaphor of the discursive node helped me support my claim that textbooks are not monovocal in a discursive and social sense. It also helps explain the surprisingly high acceptance most textbooks enjoy.

The metaphor of the node is neither static nor is it one-directional, but it lacks a quality the author is using in her/his reflections about textbooks. S/he writes of textbooks as elastic bands.

I am intrigued by the idea of elasticity, because it invokes the image of (discursive) movement, a neglected dimension which connects textbooks to society: time. Exploring the elastic band against the background of the node, I want to understand how the author’s thoughts impact a critical and self-critical perspective on textbook production and research. Hopefully, the elastic band and the node complement each other in such a way that they contribute to a narratively and socially more just product: the textbook of the future.

The author’s perspective represents a recent, novel way of looking at textbooks: S/he argues that we must not only look at the surface structures of a text, such as the words it uses, the selection of images, or explicit judgements about past events, people and places, even design.[3] Rather, we should take notice of what production processes and the material properties of the medium, such as print or digital, “do” to a textbook’s message.

One example the author uses is the order of textbook chapters: a both hierarchical and linear structure orients printed and digital books. S/he argues that the linear order stems from the material qualities of printed books: They consist of individual pages, bound in such a way that moving through content means turning one page after the other, proceeding from the beginning to the end. Textbook publishers thus conceptualize their narratives progressively through a textbook. Linear progression is a core element of knowledge building in textbooks. Although some textbooks have a more modular structure, those books are usually designed for one specific grade. It is worthwhile, however, to distinguish between the (anticipated) use of textbooks on the production side and teachers’ everyday classroom practices I would rather describe as sampling, mixing, hybridization: They switch between chapters, books, printed and online material. Textbooks face powerful competition by folders and notebooks. Nonetheless, the logic of the print continues into the digital book.

How does hierarchic narrative progression impact educational historiography? The author writes that textbook authors struggle to fit complex, entangled histories which contest the centrality of the nation (as well as other hegemonial speaking positions) into linear chapter structures. S/he suggests that the linear order contributes to the continuation of negative power narratives.

Textbooks are elastic in the sense that they continuously pull unwanted, “traditional” is the notion the author uses, knowledge and knowledge practices into the minds of today’s children and future citizens. The metaphor of the elastic band does not primarily explain how historical narratives are generated. This is not necessary, other authors have already provided us with respective tools and insights.[4] Rather, the metaphor raises awareness for their unexpected continuities by focusing on materiality and material-based practices.

Although digital educational media differ technically-materially from the cellulose-fiber object used for centuries for teaching, and although they offer new options for knowledge organization which printed books do not have, they still pull the established, familiar structures and hence also unwanted narratives along into the “new”.

I think it would be missing the point to push away the metaphor of the elastic band by listing that not all books work in a linear way, nor do many curricula, that chronology is relevant for orientation and knowledge of chronology is a widely accepted foundation to further critical engagement with history, or that many more factors shape and consolidate the mentioned negative power narratives.

The metaphor of the elastic band is very useful in a practical and political way: What do history didactics need in order to interrupt such narratives not only at the level of the explicit – the words in a text et cetera – but also with regard to (i) the analysis and (ii) the production of digital educational media? How can didactical tools help untangle elastic-band-narratives, and conceptualize teaching use cases for multi-entry textbooks? It remains crucial to reflect on what and who is missing, how the graphic and the technological form impact the narratives and how they support elasticity. We need many teachers in many classrooms who know how to interrupt linear narratives, how to address linearity if it provokes negative effects. Teachers who know how to translate their ability to read against the grain into a safe practice they share, train, and develop with their students.

The author is already looking one step ahead. Based on recent research, s/he notes that students already resist the logic of the textbooks in front of them, the intention of its producers, sometimes even the teaching strategies in their classroom. They already are “constantly working at the elastic band” in multiple and innovative ways. I read this as a call to trust students. To see them not only as recipients and learners of deconstruction techniques, but also as initiators. The metaphor of the elastic band can thus initiate research in the classroom: What kind of knowledge does this textbook pull into the present? How can we push back and send alternative voices (whose?), narratives (whose?), facts and judgements (whose?) back to what we declare to be a past account?

The metaphor of the discursive node allows us to see that educational media are shaped by a range of diverse stakeholders. To add the image of the elastic band opens a didactical, historiographical, and political way of exploring how textbook narratives change over time. Let us find out which of the threads are more elastic than others and thus worthwhile following through from one end to the other, from one textbook to another, from one history lesson to another.

Post Scriptum: Textbooks are an educational good, produced for a globally lucrative market. Education is currently valued around $6.3 trillion U.S. a year.[5] In a recent interview with Bob Peterson from Rethinking Schools, Angelo Gavrielatos, former leader at Education International, said that “some five or six years ago there was a meeting of venture capitalists in the U.S., and they declared […] that their new frontier was education,” because education is not just lucrative but also the most sustainable market in the world.[6] Pearson, the biggest global actor that has started off as a textbook publisher and now made a conscious decision to move almost entirely into the digital space. I wonder whether the nation as a focal point in many textbook narratives is not the worst version we have. How are such global educational players held accountable? How do (we as) textbook authors work with them, or as teachers with their products? The author points to the nationalistic, colonial narratives – what else should we focus our analytic attention, our research, and our didactic development on?

___________

[1] Alexandra Binnenkade, “Doing Memory: Teaching as a discursive node,” Journal of Educational Media and Memory, and Society 7, no. 2 (2015): 29-43.

[2] Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2016), 9-29.

[3] Theo van Leeuwen, “The Schoolbook as a Multimodal Text,” Internationale Schulbuchforschung 14, no. 1 (1992): 35-58.

[4] Pierre Bourdieu and Jean Claude Passeron, Reproduction in Education, Society, and Culture (London: Sage Publications, 1990). Michael Apple, The Politics of the Textbook (New York: Routledge, 1991). Michael Apple, Ideology and Curriculum (New York: Routledge, 2004). Henry Giroux, On Critical Pedagogy (New York: Continuum International Publishing, Group 2011). Mario Carretero, Stefan Berger and Maria Grever, eds., Palgrave Handbook of Research in Historical Culture and Education (London: Palgrave Macmillian, 2017).

[5] Bob Peterson, “Education and Social Justice: A Global View,” Rethinking Schools 35, no. 2 (2020): 34-38.

[6] Bob Peterson, “Education and Social Justice: A Global View,” Rethinking Schools 35, no. 2 (2020): 35.

_________________________________

Schulbücher, schreibt die Autorin/der Autor, ziehen Narrative der Vergangenheit in die Gegenwart, weil sie jenen langfristigen Logiken der Wissensproduktion folgen, die neue Darstellungen in alten Mustern präsentieren. Die Autorin/der Autor steht dieser wortwörtlichen “Tradition” kritisch gegenüber und hebt hervor, dass damit gesellschaftlich und politisch schädliche Narrative wiederholt und gefestigt werden, die von vielen Schulbuchautor:innen heute höchstwahrscheinlich abgelehnt würden: nationalistische, koloniale, homogenisierende historische Narrative in Bezug auf Rasse, Geschlecht, Klasse und andere Machtkategorien. Sie oder er argumentiert, dass, selbst wenn Schulbuchautoren solchen Narrativen kritisch gegenüberstehen, die materiell-diskursiven Verhältnisse so dominant sind, dass sie diese trotzdem reproduzieren.

Als ich kürzlich argumentierte, dass Schulbücher diskursive Knoten sind (discursive nodes), wollte ich damit herausheben, das Schulbücher das Resultat vielfältiger Verflechtungen sind. Ich zeigte, dass Schulbücher verdichtete Produkte sind, sozial und materiell zugleich, in denen ganz unterschiedliche (im Englischen kann man von “diverse” sprechen und damit eine weitere Dimension von Vielfalt ins Spiel bringen) diskursive Fäden und Praktiken zusammenkommen. Dies geschieht im Hinblick auf bestimmte Themen und Bildungsabsichten. Zusammenkommen heisst interagieren, das heisst, die Mischung ist zeitlich und inhaltlich spezifisch und damit nicht notwendigerweise stabil.[1]

Methodisch-metaphorisch skizzierte ich eine ganze Menge von Fäden, die sich auf komplexe, nicht immer verständliche Weise verflechten. Jeder Faden repräsentiert einen Akteur, der zur Schulbuchproduktion beiträgt: Individuen, Wissensgemeinschaften, Institutionen, kurz alle diskursiven Akteure die für die Erzeugung von historischem Wissen in der Schule relevant sind. Gerade weil diese Akteure und ihre diskursiven Fäden so vielfältig sind, entsteht aus ihrer Kombination Wissen, das für bestimmte Gemeinschaften zu einer bestimmten Zeit und an einem bestimmten Ort wahr ist.[2] Die Metapher des diskursiven Knotens half mir, meine Behauptung zu belegen, dass Schulbücher in einem diskursiven und sozialen Sinn nicht einstimmig sind. Sie hilft auch, die überraschend hohe Akzeptanz zu erklären, welche die meisten Schulbücher genießen.

Die Metapher des Knotens ist weder statisch noch ist sie eindimensional, aber es fehlt eine Eigenschaft, die die Autorin/der Autor/ in ihren/seinen Überlegungen über Schulbücher verwendet. Sie/er bezeichnet Schulbücher als Gummibänder.

Ich bin von der Idee der Elastizität fasziniert, weil sie ein Bild von (diskursiver) Bewegung hervorruft. Sie bringt eine vernachlässigte Dimension ins Spiel: Zeit. Ich möchte das Gummiband zum diskursiven Knoten in Verbindung bringen und dadurch verstehen, wie die Überlegungen der Autorin, des Autors eine (selbst)kritische Perspektive auf Schulbuchproduktion und -forschung begünstigen. Im besten Fall ergänzen sich die beiden Metaphern so, dass sie zu einem narrativ und gesellschaftlich gerechteren Produkt beitragen: dem Schulbuch der Zukunft.

Die Perspektive der Autorin/des Autors repräsentiert eine neuartige Sichtweise auf Schulbücher: Sie/er argumentiert nämlich, dass wir nicht nur die Oberflächenstrukturen eines Textes betrachten dürfen, also beispielsweise die verwendeten Worte, die Auswahl der Bilder oder explizite Urteile über vergangene Ereignisse, Personen und Orte, sogar das Design.[3] Vielmehr sollten wir darauf achten, was Produktionsprozesse und die materiellen Eigenschaften des Mediums (gedruckt oder digital) die Botschaft eines Schulbuchs mitprägen. Obwohl sich digitale Bildungsmedien technisch-materiell von dem jahrhundertelang für den Unterricht genutzten Zellulosefaser-Objekt unterscheiden und obwohl sie Möglichkeiten der Wissensorganisation bieten, die das gedruckte Buch nicht hat, ziehen sie die etablierten, gewohnten Strukturen und damit auch unerwünschte Narrative mit ins “neue” Lehrmittel.

Ein Beispiel, das sie/er verwendet, ist die Reihenfolge der Lehrbuchkapitel: Gedruckte wie auch digitale Bücher orientieren sich an einer Struktur, die sowohl hierarchisch als auch linear Struktur ist. Die lineare Ordnung resultiert aus den materiellen Eigenschaften gedruckter Bücher resultiert: Sie bestehen aus einzelnen Seiten, die so zusammengefügt sind, dass man während man Seite um Seite durchblättern auch zugleich Schritt für Schritt den Inhalt kennenlernt. Schulbuchverlage konzipieren ihre Erzählungen also progressiv. Die lineare Progression ist ein Kernelement davon, wie in Lehrmitteln Wissen aufgebaut wird, schreibt die Autorin/der Autor. Zwar gibt es auch Lehrbücher mit einem modularen Konzept, doch bleiben diese Module in einem engen Rahmen, denn Schulbücher sind in der Regel für eine bestimmte Klassenstufe konzipiert. Dennoch lohnt es sich, zwischen der (antizipierten) Verwendung von Schulbüchern auf der Produktionsseite und der alltäglichen Unterrichtspraxis von Lehrpersonen zu unterscheiden. Diese Praxis würde ich eher als Sampling, Mischen, Hybridisieren beschreiben: Sie wechseln zwischen Kapiteln, Büchern, gedrucktem und Online-Material. Das Lehrmittel, aus dem viele Schüler:innen lernen, ist oft nicht ein Buch, sondern ein Ordner oder ein Heft. Trotz dieses Einwands aus der Praxis hat die Autorin/der Autor recht: Die Logik des Gedruckten setzt sich im digitalen Buch fort.

Wie wirkt sich die hierarchische Erzählprogression inhaltlich aus? Die Autorin/der Autor schreibt, dass Schulbuchautor:innen damit kämpfen, komplexe, verwickelte Erzählungen, die die Zentralität der Nation (sowie andere hegemoniale Sprechpositionen) anfechten, in lineare Kapitelstrukturen einzupassen. Ihrer/seiner Ansicht nach trägt die lineare Ordnung zur Fortführung negativer Machtnarrative bei.

Schulbücher sind elastisch in dem Sinn, dass sie kontinuierlich unerwünschtes, im originalen Beitrag ist die Rede von “traditionellem” Wissen in die Köpfe heutiger Schüler:innen und zukünftigen Bürger:innen ziehen. Die Metapher des Gummibandes erklärt nicht in erster Linie, wie historische Narrative entstehen. Das ist auch nicht nötig, andere Autor:innen haben uns bereits entsprechende Werkzeuge und Einsichten geliefert.[4] Vielmehr schärft die Metapher das Bewusstsein und zeigt, wie unwillkommene Kontinuitäten entstehen, indem sie den Fokus auf Materialität und materialbasierte Praktiken legt.

Es wäre verfehlt, die Metapher des Gummibandes zurückzuweisen, indem man daran erinnert, dass weder alle Bücher noch alle Lehrpläne linear funktionieren, dass Chronologie für die Orientierung relevant ist und dass chronologisches Wissen eine weithin akzeptierte Grundlage für die weitere kritische Auseinandersetzung mit Geschichte ist, oder dass viele weitere Faktoren die erwähnten negativen Machtnarrative formen und verfestigen.

Die Metapher des Gummibandes ist in praktischer, politischer und fachlicher Hinsicht sehr nützlich: Was braucht die Geschichtsdidaktik, um solche Narrative nicht nur auf der Ebene des Expliziten zu unterbrechen, sondern auch im Hinblick auf (i) die Analyse und (ii) die Produktion von digitalen Bildungsmedien? Wie können didaktische Werkzeuge dabei helfen, die Elastizität von Schulbüchern zu beenden? Welche didaktischen Anwendungsfälle können wir für Multi-Entry-Lehrbücher konzipieren? Es bleibt entscheidend, gut und kritisch darüber nachzudenken, was und wer in einer historischen Erzählung fehlt, wie grafische und technologische Formen die Narrative beeinflussen und wodurch die kritisierte Elastizität unterstützt wird. Es braucht viele Lehrpersonen in vielen Klassenzimmern, die Bescheid wissen, wie sie lineare Narrative unterbrechen können, wie sie Linearität ansprechen, sobald sie negative Effekte provoziert. Lehrerinnen und Lehrer, die wissen, wie sie ihre historische Kompetenz, gegen den Strich zu lesen, in eine sichere Unterrichtspraxis umsetzen können, die sie mit ihren Schüler:innen teilen, trainieren und weiterentwickeln.

Die Autorin/der Autor blickt bereits einen Schritt voraus. Basierend auf neuen Forschungsergebnissen stellt sie/er fest, dass Schüler:innen bereits der Logik der vor ihnen liegenden Lehrbücher, der Intention ihrer Produzent:innen, manchmal sogar den Unterrichtsstrategien in ihrem Klassenzimmer widerstehen. Sie arbeiten auf vielfältige und innovative Weise bereits “ständig am Gummiband”. Ich verstehe dies als Aufruf, den Schüler:innen zu vertrauen. Sie nicht nur als Rezipient:innen und Lernende von Dekonstruktionstechniken zu sehen, sondern auch als Initiator:innen. Die Metapher des Gummibandes kann also eine Forschung im Klassenzimmer in Gang setzen: Welches Wissen zieht dieses Schulbuch in die Gegenwart? Wie können wir dem entgegenwirken und alternative Stimmen (wessen?), Erzählungen (wessen?), Fakten und Urteile (wessen?) in die vergangene Darstellung zurückschicken?

Die Metapher des diskursiven Knotens erlaubt es uns zu erkennen, dass Bildungsmedien von einer Reihe unterschiedlicher Akteure geprägt werden. Fügt man diesem Verständnis das Bild des Gummibandes hinzu, dann eröffnet das einen didaktischen, historiographischen und politischen Weg, um zu untersuchen, wie sich Schulbuchnarrative im Laufe der Zeit verändern. Lassen Sie uns herausfinden, welche Fäden elastischer sind als andere und dass es sich daher lohnt, sie von einem Ende zum anderen, von einem Schulbuch zum anderen, von einer Geschichtsstunde zur anderen zu verfolgen.

Post Scriptum: Schulbücher sind ein Bildungsgut, produziert für einen weltweit lukrativen Markt. Bildung wird derzeit mit rund 6,3 Billionen US-Dollar pro Jahr bewertet.[5] In einem Interview mit Bob Peterson von Rethinking Schools sagte Angelo Gavrielatos, ehemaliger Leiter von Education International, kürzlich, dass “vor etwa fünf oder sechs Jahren ein Treffen von Risikokapitalgebern in den USA stattfand, und sie erklärten […], dass ihr neues Ziel [frontier] die Bildung sei”, denn Bildung sei nicht nur lukrativ, sondern auch der nachhaltigste Markt der Welt.[6] Ein Beispiel dafür ist Pearson, der größte globale Bildungs-Akteur, der als Schulbuchverlag begonnen hat und nun entschieden hat, fast vollständig ins Digitale zu investieren. Ich frage mich, ob die Nation/der Nationalstaat als Fluchtpunkt in vielen Schulbuchnarrativen nicht einmal die schlechteste Variante ist, die wir haben. Wie werden solche globalen Bildungsakteure zur Verantwortung gezogen? Wie arbeiten (wir als) Schulbuchautor:innen mit ihnen, oder als Lehrer:innen mit ihren Produkten? Die Autorin/der Autor verweist kritisch auf die nationalistischen, kolonialen Narrative. Angesichts der globalen Märkte frage ich, worauf sollten wir unsere analytische Aufmerksamkeit, unsere Forschung und unsere didaktische Entwicklung ausserdem richten, wenn wir uns mit Schulbüchern beschäftigen?

___________

[1] Alexandra Binnenkade, “Doing Memory: Teaching as a discursive node,” Journal of Educational Media and Memory, and Society 7, no. 2 (2015): 29-43.

[2] Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2016), 9-29.

[3] Theo van Leeuwen, “The Schoolbook as a Multimodal Text,” Internationale Schulbuchforschung 14, no. 1 (1992): 35-58.

[4] Pierre Bourdieu and Jean Claude Passeron, Reproduction in Education, Society, and Culture (London: Sage Publications, 1990). Michael Apple, The Politics of the Textbook (New York: Routledge, 1991). Michael Apple, Ideology and Curriculum (New York: Routledge, 2004). Henry Giroux, On Critical Pedagogy (New York: Continuum International Publishing, Group 2011). Mario Carretero, Stefan Berger and Maria Grever, eds., Palgrave Handbook of Research in Historical Culture and Education (London: Palgrave Macmillian, 2017).

[5] Bob Peterson, “Education and Social Justice: A Global View,” Rethinking Schools 35, no. 2 (2020): 34-38.

[6] Bob Peterson, “Education and Social Justice: A Global View,” Rethinking Schools 35, no. 2 (2020): 35.

To all our non-English speaking readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 11 languages. Just copy and paste.

Author’s Reply

I thank Alexandra Binnenkade for the thought-provoking open peer review. The concept of ‘discursive node’ also captures beautifully the observations I made when I was doing ethnographic research at the major textbooks publishing houses in Germany [1]: the multiple material and semiotic threads, flows and practices that play into the knowledges and the stories which, as Alexandra writes, ‘sounds true to specific communities at a specific time and place’. I agree, it is, indeed, all very plural and multiple during the development stages.

With the ‘elastic textbooks’, I was trying specifically to highlight the pull of past practices. I drew in some writing back then on Halbwachs’ notion of the ‘echo’ to try to highlight on the role of these past memory practices, but an echo is fleeting, it vanishes after a short time. Elastic practices are stabilized, they move and stretch, but they are also held in place. Even if everyone around the table explicitly states that they want to overturn these very practices.

Alexandra also rightly points to the hybrid, sampling uptake by teachers. This can, I completely agree, snip the elastic band in two. But, I would suggest, in everyday teaching, by those teachers who are not activists, it doesn’t often. (And, saying this, I should note, I don’t expect teachers to be activists, their priority is to be teachers of students!) Partly because the alternative materials that teachers are using are developed in the same way: Often, teachers mix and mashup the materials that fit their specific learning focus and their specific classes from other published textbooks or other officially published materials.

A key movement here could be OER. A student of mine recently compared the representation of migration in current textbooks and teacher-generated OER. She only found explicitly anti-racist materials in the OER. Admittedly, this was a very small sample, and it would be fantastic if research undertook a more systematic analysis, but I found this very intriguing. The OER is far less of a discursive node, it is far more in the hands of one specific teacher. And here we find high quality teaching materials that ‘sound true’ to a slightly different community, with powerful knowledge-making effects.

I appreciate this comment: “We need many teachers in many classrooms who know how to interrupt linear narratives, how to address linearity if it provokes negative effects. Teachers who know how to translate their ability to read against the grain into a safe practice they share, train, and develop with their students.” I would add that one dimension of this is that, although many teachers know how to interrupt linear narratives, they sometimes underestimate how students are interpreting their (teachers’) narratives or explanations as linear. Here, some strong examples have been analysed for history teaching, in which it becomes clear that the teacher aims to interrupt, aims to address a problematic linearity and aims to shape a safe space. But she has no access to how her students read and hear.

Linking this to teaching during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, in other studies we have heard from students that in some schools, only a few teachers asked them, how they were dealing with the work, if it was manageable amounts. And perhaps there is even a parallel to Cockpit Resource Management: the dramatic shift in aviation to remove the absolute authority from the captain of the plane. In many school cultures today, teachers co-teach, and invite participation from their students. In other school cultures, the teacher still has complete authority to decide autonomously. This authority/participation nexus is perhaps also part of the discursive node that we are discussing here.

The review ends with a PS which opens a massive issue for education (or educational technology) today: The discursive node is getting more and more complex, it is integrating powerful global actors, with clear ideas of what ‘good education’ should be. These ideas are being encoded into the very fabric of the technology used in schools. This adds a whole new elastic band, on top of the elastic band we have been discussing: This new elastic band is connected to what has been called the Californian ideology [3]. It in turn opens up a new ‘frontier’ for textbooks users, writers, activists and analysts.

_______________________________________

[1] Macgilchrist, F. (2011). Schulbuchverlage als Organisationen der Diskursproduktion: Eine ethnographische Perspektive [Educational publishers as organisations of discourse production: An ethnographic perspective]. Zeitschrift für Soziologie der Erziehung und Sozialisation, 31(3), 248-263. Macgilchrist, F. (2017). Textbook Production: The entangled practices of developing educational media for schools. Eckert.Dossiers 15/2017, https://repository.gei.de/handle/11428/267

[2] Mielke, P. (2020). Die Aushandlung von Zugehörigkeit und Differenz im Geschichtsunterricht. Eine ethnographische Diskursanalyse. Goettingen Universität. DOI: http://hdl.handle.net/21.11130/00-1735-0000-0005-1349-4

[3] Barbrook, R. & Cameron, A. (1995). The Californian Ideology. Mute, 1(3). http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/californian-ideology.