Abstract:

The key participants of the public discussions about the past in contemporary Russia are both official state institutions and public memorial and urban projects. The concept of cultural heritage has a defining role in their discourses and practices. Though participants appeal to the international definitions of cultural heritage adopted by UNESCO, their interpretations and uses vary. It impedes public discussions about the past in general and heritage in particular in Russia.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-19140

Languages: English, Russian

Мы анализируем интерпретации и пути использования концепции культурного наследия в дискурсах и практиках государственных институтов и публичных мемориальных проектов в России на пересечении двух исследовательских программ[1]: public history и critical heritage studies. Применение подходов публичной истории позволяет изучить проблему «разделяемой власти» (shared authority),[2] которая крайне важна при изучении негосударственных публичных форм разговора о прошлом и наследии.

Критические исследования наследия (critical heritage studies)

Понятие культурного наследия играет определяющую роль и в практиках, и в дискурсах российских мемориальных проектов. Лораджейн Смит, австралийский археолог и ведущий теоретик critical heritage studies, указывает на то, что культурное наследие –продукт культурной политики, а не некое свойство того или иного памятника.[3] Для описания использования данного понятия она ввела термин «авторизованный дискурс наследия». Он маркирует механизм, посредством которого обладающий авторитетом эксперт, «законный представитель прошлого», идентифицирует (и одновременно с этим конструирует) якобы очевидную «врожденную» ценность объектов наследия.

В результате критики «авторизованного дискурса наследия» культурное наследие стало пониматься как социальное действие, что подразумевает требование отказа от монополизации права экспертов (обычно закрепленного на государственном уровне) на определение и признание того или иного объекта частью культурного наследия. Одновременно с этим представители critical heritage studies указывают на внутренние противоречия официального дискурса, невозможного без асимметричных властных отношений. Он не предлагает ни четкого распределения власти во взаимоотношениях между администраторами, экспертами и активистами, ни последовательных эпистемологических оснований концепции наследия, которые бы дали возможность публичного обсуждения изменений этого понятия.

Авторизованный дискурс наследия в России

В России ключевым центром «авторизации» и изучения культурного наследия является Российский научно-исследовательский институт культурного и природного наследия имени Д.С. Лихачёва, созданный в 1992 г. Министерством культуры РФ для реализации положения Конвенции ЮНЕСКО «Об охране Всемирного культурного и природного наследия».[4] Институт стал преемником Советского фонда культуры и Российского института культурологии, одной из его основных задач стало составление реестров объектов культурного наследия в России в постсоветское время. Институт стал главной государственной организацией, осуществляющей сотрудничество с ЮНЕСКО в рамках программы Всемирного наследия (World Heritage sites). Поскольку СССР практически не участвовал в проектах ЮНЕСКО и оставался terra incognita на карте объектов всемирного наследия (World Heritage map) до окончания холодной войны, Институт содействовал включению России в основные международные программы.[5]

С 2015 г. в рамках реализации Указа Президента Российской Федерации от 24.12.2014 г. № 808 «Об утверждении Основ государственной культурной политики» программа Института наследия им. Д.С. Лихачёва включает задачу изучения наследия «российской цивилизации» в контексте «революционных трансформаций, угрожающих идентичности и историческому самосознанию нации».[6] Это предполагает де факто формирование собственной системы оценивания наследия. Впервые это стало очевидно на примере обоснования необходимости передаче культурного и исторического наследия Крыма России после событий 2014 г.[7] В работах Института культурная значимость памятников Крыма обосновывается через апелляцию к универсальным категориям аутентичности, исторической и культурной ценности для потомков, закрепленных в документах ЮНЕСКО. Обоснование же юридического статуса памятников Крыма происходит на основе российских, а не международных правовых норм. Таким образом, государственные институты России используют внутренние противоречия «авторизованного дискурса наследия», сохраняя закрепленное в международном праве определение культурного наследия.

Мемориальные проекты и «неудобное прошлое»

Существующие на данный момент в России публичные проекты, связанные с наследием, условно можно разделить на два типа. Первый тип в большей степени сосредоточен на изучении «неудобного прошлого»[8] – прежде всего, памяти о жертвах государственных репрессий. Так, гражданская инициатива «Последний адрес»[9] с 2013 г. объединяет историков, культурологов, общественных деятелей и горожан, заинтересованных в изучении и обозначении на карте России мест (не ограничиваясь только лишь Москвой), связанных с «неудобным прошлым». Деятельность проекта нацелена на введение в российскую публичную сферу информации о государственных репрессиях. Результатом этой работы стало установление памятных табличек репрессированным и умершим в заключении в советское время, что не входит в сферу деятельности ни Института наследия, ни Министерства культуры, то есть «авторизованного дискурса наследия». Установлено уже несколько сотен таких табличек и подано еще несколько десятков заявок на установку таких табличек. Проект регулярно сталкивается с трудностями установки мемориальных табличек на зданиях, которые внесены в реестры объектов культурного наследия и находятся под государственной охраной.

С трудным прошлым также работает проект «Это прямо здесь»[10] (прежнее название – «Топография террора», отсылавшее к одноименному берлинскому проекту), который был создан в 2013 г.[11] на базе международного историко-просветительского и правозащитного общества «Мемориал». Центральной задачей проекта является не только составление онлайн-карты мест, связанных с государственными репрессиями в СССР, но шире – осмысление специфики несвободы человека в условиях советского государства. Топографическая оптика позволяет сделать десятки историй репрессированных в Москве ближе современному горожанину и гражданину. В публикациях на сайте и деятельности проекта регулярно противопоставляются разные аспекты понятия «культурного наследия». С одной стороны, в описании топографии Москвы фигурируют конструктивистские постройки и постройки в духе «сталинского ампира» как «сталинского», «советского» наследия и «наследия культа». С другой стороны, онлайн-карта призвана расширить представление об этом наследии, показать его «оборотную сторону» через указание тех мест, которые были связаны с жертвами репрессий, тюрьмами и любыми проявлениями несвободы в условиях тоталитарного режима.

Несмотря на то, что в данных проектах преобладает фокус на категории памяти, именно память о трудном, неудобном и травматичном прошлом в риторике данных проектов рассматривается как советское наследие, которое требует осмысления на разных уровнях – публичном и государственном.

Архитектурное и городское наследие

Второй тип публичных проектов, связанных с наследием, в России составляют градозащитные общественные организации, которые ставят своей целью сохранение исторических построек, представляющих культурную ценность и находящихся под угрозой. Проект «Москва, которой нет»[12] был начат в 2003 г. московскими краеведами и стал первой попыткой объединить исследователей и активистов, которые были озабочены сносом или перестройкой памятников архитектуры в столице, Подмосковье и в других российских городах. Участники проекта интересуются не только культурной ценностью отдельных построек или городских районов, но и тем, какое значение они имели и имеют для горожан. За прошедшие годы проект привлек внимание к широкой агентности определения понятия культурного наследия, обращая внимания на разные социальные группы, включенные в процессы означивания городского пространства и отдельных мест. «Москва, которой нет» организует регулярные экскурсии и поездки, связанные с разным наследием: от более конвенционального литературного, церковного, монастырского и архитектурного до университетского и промышленного.

Проект «Архнадзор»[13] возник в 2009 г. благодаря деятельности проекта «Москва, которой нет», объединив не только исследователей и краеведов, но и активных горожан, заинтересованных в защите и охране отдельных строений Москвы. Среди ключевых результатов работы проекта – «Красная книга Архнадзора», перечень находящихся под угрозой уничтожения и защищенных объектов культурного наследия Москвы, и «Черная книга Архнадзора», перечень утраченных объектов культурного наследия Москвы. Проект апеллирует к официальному определению культурного наследия и принципам защиты и охраны культурного наследия, разработанными ЮНЕСКО. Однако он обращает внимание и на то, как горожане разных поколений определяют и оценивают разные места и постройки в Москве. Проект выступает как общественное движение, которое организует публичные выступления против сноса и некорректной реставрации разных памятников, оспаривая «авторизованный дискурс наследия». Примечателен недавний пример дискуссии, которую начал «Архнадзор» вокруг проекта реконструкции павильона «Шестигранник» в Парке Горького в Москве.[14] Павильон – памятник раннесоветской архитектуры, но не включен в реестры объектов наследия и долгие годы находился в заброшенном состоянии. Музей современного искусства «Гараж» предложил проект реконструкции «Шестигранника», что помогло бы создать новые выставочные залы. Реконструкция была одобрена Департаментом культурного наследия Москвы, однако результаты экспертизы в открытом доступе опубликованы не были. Проведя собственную экспертизу проекта реконструкции павильона, участники «Архнадзора» высказали опасения о том, что данная реконструкция будет проведена корректно и позволит сохранить исторический облик здания, призывая к необходимости публичной дискуссии с участием горожан о том, как и для кого необходимо реконструировать «Шестигранник».

Участники обоих проектов не подвергают критике позицию эксперта и связанных с ним «авторизованных дискурс наследия», однако уделяют большое внимание возможностям разделения власти в определении наследия с заинтересованными сообществами горожан.

Сложность публичной дискуссии о прошлом в России характеризуется различным отношением мемориальных и градозащитных проектов с глобальным и национальным (российским) уровнем «авторизованного дискурса наследия». Кроме того, пользуясь возможностями внутренних противоречий «авторизованного дискурса наследия», участники проектов обращают внимание на разные аспекты наследия, акцентируя его материальность и нематериальность. Первый тип мемориальных проектов стремится к переосмыслению и расширению понятия наследия. Во многом их понимание наследия можно сопоставить с интерпретациями, предлагаемые critical heritage studies. Второй тип проектов, несмотря на использование «авторизованного дискурса наследия», адаптирует практики публичной истории, выступая посредниками между государством и обществом в публичных дискуссиях о наследии.

_____________________

Литература

- Geering, Corinne. Building a Common Past. World Heritage in Russia under Transformation, 1965-2000. Göttingen: V&R unipress GmbH, 2019.

- Smith, Laurajane. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge, 2006.

Ссылки в Интернете

- Arhnadzor [Architectural supervision]: http://www.archnadzor.ru (last accessed 13 December 2021).

- Rossiyskiy Institut nasledija [Russian Heritage Institut]: https://heritage-institute.ru (last accessed 13 December 2021).

- Moskva, kotoroj net [The Moscow That Doesn’t Exist]: https://moskva.kotoroy.net (last accessed 13 December 2021).

_____________________

[1] В статье использованы результаты, полученные в ходе выполнения работы по гранту № МК‑1474.2021.2 в рамках программы грантов Президента Российской Федерации для государственной поддержки молодых российских ученых — кандидатов наук (конкурс — МК‑2021).

[2] Michael Frisch, A Shared Authority: Essays on the Craft and Meaning of Oral and Public History (New York: State University of New York Press, 1990).

[3] Laurajane Smith, Uses of Heritage (London: Routledge, 2006).

[4] Институт наследия: https://heritage-institute.ru (дата обращения 15.11.2021).

[5] Corinne Geering, Building a Common Past. World Heritage in Russia under Transformation, 1965-2000. (Göttingen: V&R unipress GmbH, 2019), 32.

[6] Закунов, Ю.А. Наследование ценностей культуры и цивилизации: о новом содержании НИР в Институте Наследия // Журнал института наследия. 2018. №3(14). С. 1.

[7] Gertjan Plets, “Ethno-nationalism, asymmetric federalism and Soviet perceptions of the past: (World) heritage activism in the Russian Federation,” Journal of Social Archaeology, 15, no. 1 (2015): 67-93.

[8] Эппле, Н. Неудобное прошлое. Память о государственных преступлениях в России и других странах. Москва: Новое литературное обозрение, 2020.

[9] Последний адрес [Электр. ресурс]. Режим доступа: https://www.poslednyadres.ru, свободный (дата обращения 15.11.2021).

[10] Это прямо здесь: https://topos.memo.ru (дата обращения 11.11.2021).

[11] Поливанова, А., Петрова, Н. «ГУЛАГ — это прямо здесь»: о проекте «Топография террора» // Фольклор и антропология города. 2019. № II(1–2). С. 362–373.

[12] Москва, которой нет: https://moskva.kotoroy.net (дата обращения 11.11.2021).

[13] Архнадзор: http://www.archnadzor.ru (дата обращения 11.11.2021).

[14] «Шестигранник»: нужна дискуссия // Архнадзор. 24.11.2021. http://www.archnadzor.ru/2021/11/24/shestigrannik-nuzhna-diskussiya/#more-36719 (дата обращения 25.11.2021).

_____________________

Авторы фотографий

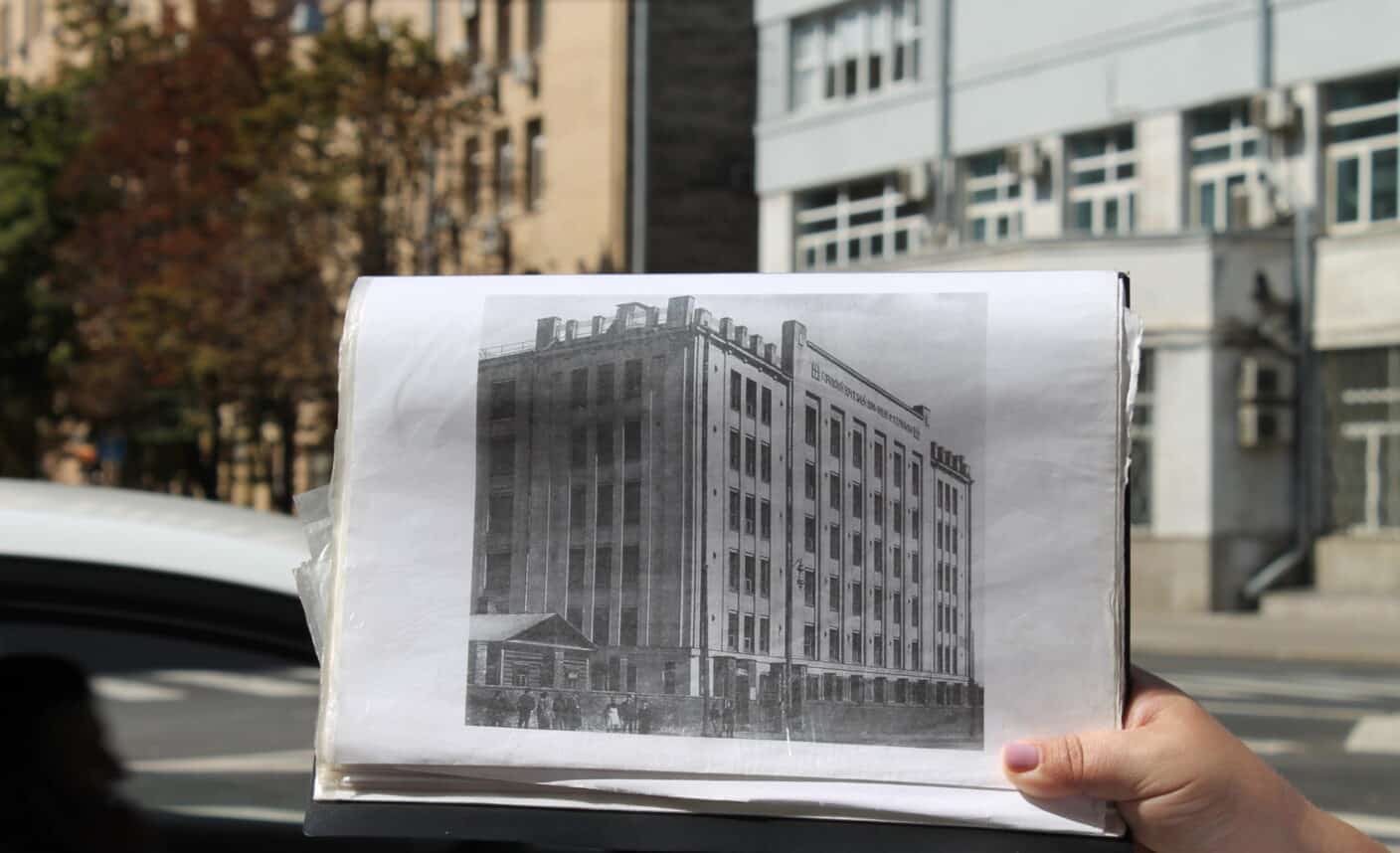

Москва, которой нет, экскурсия © 2021 The Authors.

Рекомендация для цитирования

Kolesnik, Alexandra Sergeevna, Aleksanr Vitalievich Rusanov: Использование понятия культурного наследия в мемориальных и градозащитных проектах в России. In: Public History Weekly 9 (2021) 10, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-19140.

Редакционная ответственность

We analyse how the concept of cultural heritage is interpreted and used by both official state institutions and public memorial projects.[1] Our investigation lies at the intersection of two research programs: public history and critical heritage studies. The public history approaches allow us to study the problem of “shared authority,”[2] which is extremely important for the study of non-state public forms of talking about the past and heritage.

Critical Heritage Studies

The concept of cultural heritage has a decisive role in both the practices and discourses of Russian memorial projects. Laurajane Smith[3], Australian archaeologist and leading theorist of the critical heritage studies, notes that cultural heritage is a product of cultural policy, and not an essential feature of a particular monument. She proposed the term of the “authorized heritage discourse” (AHD) to describe this process. The AHD marks the discursive strategy by which an authoritative expert, a “legitimate representative of the past,” identifies (and at the same time constructs) the ostensibly obvious “innate” value of heritage monuments, sites and practices. At the same time, the critical heritage studies emphasise the internal contradictions of the AHD, which is impossible without asymmetrical power relations. It provides neither an explicit distribution of power between administrators, experts and activists, nor any consistent epistemological foundation of the “cultural heritage” concept, that would facilitate public discussion about its transformation.

Authorized Heritage Discourse (AHD) in Russia

In Russia, the key centre for “authorization” and study of cultural heritage is Likhachev Research Institute for Cultural and Natural Heritage[4], founded in 1992 by the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation to implement the UNESCO World Heritage Convention. While “the Soviet Union remained a blank space on the World Heritage map until the end of the Cold War,”[5] the Institute contributed to the inclusion of Russia in the international heritage programs. It became successor of the Soviet Culture Fund and the Russian Institute for Cultural Studies, revising the cultural heritage lists in the post-Soviet period. The Institute is the main state organization cooperating with UNESCO in the framework of the World Heritage Sites program.

Since 2015, the program of the Russian Heritage Institute includes the task of comprehending heritage of “Russian civilization” in the context of “revolutionary transformations that threaten the historical identity of the nation.”[6] This transformation was associated with the implementation of the Decree of the President of the Russian Federation No. 808 (December 24, 2014) “On Approval of the Fundamentals of State Cultural Policy.” It presupposes formation of Russia’s own system of heritage assessment, which directly contradicts the cultural policy of UNESCO. These changes became evident during the justifying of the transfer of the cultural and historical heritage of Crimea to Russia after 2014.[7] Within the work of the Institute, the cultural significance of the Crimean monuments is substantiated through the universal categories of authenticity, historical and cultural value for descendants, enshrined in UNESCO documents. The substantiation of the legal status of the Crimean monuments is based on Russian, not international legal norms.

Memorial Projects and “Inconvenient Past”

In Russia, public projects related to heritage can be conditionally divided into two types. The first type is more focused on studying the “inconvenient past” (neudobnoe proshloe)[8]–firstly, memory of victims of political repressions. Since 2013, the civil initiative “Last Address” (Posledniy adres)[9] has been bringing together historians, public intellectuals and citizens interested in marking places associated with “inconvenient past” on the map of Russia. The project is aimed at introducing information about state repressions into the Russian public sphere. The result of this work is the establishment of memorial signs for the repressed and those who died in prison during the Soviet period, which is outside the scope of activities of the AHD–either the Heritage Institute or the Ministry of Culture. Several hundreds of such signs have already been installed and several dozen more applications have been submitted. The project regularly encounters difficulties in installing memorial signs on buildings that are included in the cultural heritage lists and are under state protection.

The project “It’s Right Here”[10] (Eto pryamo zdes’),[11] which was created in 2013 on the basis of the international historical society “Memorial,” is also focused on “inconvenient past.” Its central task is not only to compile an online map of places associated with state repressions in the USSR, but more broadly–to comprehend human lack of freedom in the Soviet state.[12] Topographic optics gives possibility to make dozens of stories of the repressed in Moscow closer to the modern city dwellers and citizens. In their online publications and activities, different aspects of the concept of “cultural heritage” are regularly contrasted. On the one hand, constructivism and Stalinist architecture are marked as the “Stalinist” and “soviet” heritage. On the other hand, the online map is designed to broaden the understanding of this heritage, to show its “downside” by indicating the places associated with victims of political terror that are right here, in Moscow and other cities.

Despite the fact that the focus on memory prevails in these projects, it is the memory of difficult, inconvenient and traumatic past that is considered in the rhetoric of these projects as a Soviet legacy and heritage[13] that requires understanding at different levels, public and state.

Architectural and Urban Heritage

The second type are urban protection public projects that aim to preserve historical buildings of cultural value. “The Moscow That Doesn’t Exist”[14] (Moskva, kotoroy net) project was launched in 2003 by Moscow local historians and was the first attempt to unite researchers and activists who were concerned about the demolition or rebuilding of architectural monuments in Moscow and other Russian cities. The project participants are interested not only in the cultural value of buildings or urban areas, but also in what significance they had and have for the citizens. Over the years, the project has been legitimising the broad agency of defining the concept of cultural heritage, paying attention to different social groups included in the processes of denoting urban spaces and places. The project organizes regular tours related to different heritage: from the more conventional literary, ecclesiastical, monastic and architectural to university and industrial.

“The Arkhnadzor” (Architectural supervision)[15] project arose in 2009 thanks to the activities of “The Moscow That Doesn’t Exist” project, bringing together not only researchers and local historians, but also active citizens interested in the protection and conservation of historical buildings in Moscow. Among the key results of the project are the “Arkhnadzor Red Book” (Moscow cultural heritage under threat of destruction) and “Arkhnadzor Black Book” (list of lost cultural heritage objects in Moscow). The project appeals to the official definition of cultural heritage and the principles of its protection and conservation developed by UNESCO. However, it also pays attention to how the citizens of different generations define and evaluate different places and buildings in Moscow. “The Arkhnadzor” organizes protests against the demolition and incorrect restoration of various monuments, challenging the AHD. Notable is the recent discussion of the reconstruction of the Hexagon pavilion in Gorky Park in Moscow.[16] The pavilion is a monument of early Soviet architecture, but it is not included in heritage sites list and was abandoned for many years. The Garage Museum of Contemporary Art proposed a project for the reconstruction of the Hexagon, which would help create new exhibition halls. The reconstruction was approved by the Moscow Department of Cultural Heritage, but the results of the examination were not published in the public domain. Having conducted their own expertise of the pavilion reconstruction project, the Arkhnadzor expressed their fears that this reconstruction would not allow preserving the historical appearance of the building, urging for public discussion about how and for whom it is necessary to reconstruct the Hexagon.

The participants in both projects do not criticize the position of the expert and the AHD associated with it, but pay great attention to the possibilities of sharing authority in defining heritage with the interested urban communities.

The complexity of public discussion about the past in Russia is characterized by the conflicting attitudes of memorial and urban projects to the global and national (Russian) levels of “authorized heritage discourse.” In addition, using the potential of the internal contradictions of the AHD, project participants scrutinise the different aspects of heritage, emphasizing its materiality or intangibility. The first type of memorial projects seeks to rethink and expand the concept of heritage. It seems to us that in many ways their understanding of heritage can be compared with the interpretations offered by critical heritage studies. The second type of projects, despite using “authorized discourse of heritage,” adapts the practices of public history, expanding agency into the debate about heritage.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Geering, Corinne. Building a Common Past. World Heritage in Russia under Transformation, 1965-2000. Göttingen: V&R unipress GmbH, 2019.

- Smith, Laurajane. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge, 2006.

Web Resources

- Arhnadzor [Architectural supervision]: http://www.archnadzor.ru (last accessed 13 December 2021).

- Rossiyskiy Institut nasledija [Russian Heritage Institut]: https://heritage-institute.ru (last accessed 13 December 2021).

- Moskva, kotoroj net [The Moscow That Doesn’t Exist]: https://moskva.kotoroy.net (last accessed 13 December 2021).

_____________________

[1] The publication was prepared within the framework of the President of the Russian Federation grants program for state support of young Russian PhD scientists and scholars (competition–MK-2021; grant No. MK-1474.2021.2).

[2] Michael Frisch, A Shared Authority: Essays on the Craft and Meaning of Oral and Public History (New York: State University of New York Press, 1990).

[3] Laurajane Smith, Uses of Heritage (London: Routledge, 2006).

[4] Russian Heritage Institute: https://heritage-institute.ru/?page_id=23674 (last accessed 15 November 2021).

[5] Corinne Geering, Building a Common Past. World Heritage in Russia under Transformation, 1965-2000. (Göttingen: V&R unipress GmbH, 2019), 32.

[6] Yuri A. Zakunov, “Nasledovanie cennostej kul’tury i civilizacii: o novom soderzhanii NIR v Institute Naslediya,” Zhurnal instituta naslediya, 3, no. 14 (2018): 1.

[7] Gertjan Plets, “Ethno-nationalism, asymmetric federalism and Soviet perceptions of the past: (World) heritage activism in the Russian Federation,” Journal of Social Archaeology, 15, no. 1 (2015): 67-93.

[8] Here we use the notion “inconvenient past” (neudobnoe proshloe) developed by Nikolay Epple in his recent book “Neudobnoe proshloe. Pamyat’ o gosudarstvennyh prestupleniyah v Rossii i drugih stranah” (Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 2020).

[9] Posledniy adres: https://www.poslednyadres.ru (last accessed 11 November 2021).

[10] Eto pryamo zdes’: https://topos.memo.ru (last accessed 11 November 2021).

[11] Previous name “Topography of Terror” referred to the Berlin project of the same name.

[12] Alexandra Polivanova and Natalia Petrova, “‘GULAG–eto pryamo zdes’’: o proekte ‘Topografiya terrora’,” Fol’klor i antropologiya goroda, II, no. 1–2 (2019): 362-373.

[13] The meaning of the Russian word “nasledie” is equal to the English words “legacy” and “heritage.”

[14] Moskva, kotoroy net: https://moskva.kotoroy.net (last accessed 11 November 2021).

[15] Arkhnadzor: http://www.archnadzor.ru (last accessed 11 November 2021).

[16] “Shestigrannik”: nuzhna diskussiya, Arkhnadzor: http://www.archnadzor.ru/2021/11/24/shestigrannik-nuzhna-diskussiya/#more-36719 (last accessed 25 November 2021).

_____________________

Image Credits

The Moscow That Doesn’t Exist tour © 2021 The Authors.

Recommended Citation

Kolesnik, Alexandra Sergeevna, Aleksanr Vitalievich Rusanov: Cultural Heritage in Russian Public Memorial Practices. In: Public History Weekly 9 (2021) 10, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-19140.

Editorial Responsibility

Copyright © 2021 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 9 (2021) 10

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-19140

Tags: Conflict of Memory, Cultural Heritage (Kulturerbe), Language: Russian, Russia (Russland)

Russian version below. To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

OPEN PEER REVIEW

At the intersection of public history and critical heritage studies

This article examines issues of non-academic and non-governmental work with the past that are highly topical for contemporary Russian civil society (although, unfortunately for many historians and civic activists, by no means nearly as topical for the rest of Russia’s population). The past, whether in the form of its representations or in the form of its material remains, is often used in Russia as a battleground for the present and the future. It is therefore not surprising that the cases to which this article pays particular attention are related to the hottest topics in the history of the relationship between the authorities and the population of Russia/USSR. The first two case studies deal with projects aimed at introducing into the public domain pieces of information about Soviet state repression, information that is largely unknown or forgotten. In this way, they do the job that the social memory could have done, if there were one. In order to introduce as correct and complete information as possible, these projects include research into the history of individuals and places, and this information is published by them on the Internet, making it available to Russian-speaking readerships around the world. Whereas the “Last address” memorial plaques contain a minimum of information, the comments on the project’s website are often larger than encyclopedic articles, and in many cases they contain more information than people’s memories that inspired the plaque’s installation. It is important to emphasize that both projects fundamentally abandon the criterion of “importance” or “celebrity” of this or that victim of repression: both the stories told within the framework of the “It’s is Right Here” project and the “Last Address” plaques tell about any people, regardless of their prominence or the role they played in the history of the country (except for the perpetrators of repression).

By contrast, the third and fourth projects discussed in the article are not so much about resurrecting the memory of people who were killed by the state during the Soviet era, but, rather, about preserving such cultural heritage sites that, in the view of activists, have artwork value as pieces of architecture or are historically interesting places associated with particularly notable events and persons of the past. Ironically, sometimes a building’s status as a protected architectural monument proves to be a hindrance to placing a “Last Address” plaque on it, the two concepts of dealing with the past thus colliding with each other.

Operating at the intersection of public history and critical heritage studies, the article convincingly uses Laurajain Smith’s concept of authorized heritage discourse (AHD) as the theoretical framework. It shows how in some cases activists challenge the state’s monopoly on authority in identifying and memorializing sites (“Last Address” relies on state authority in only one point: plaques are installed only if victims have been officially rehabilitated), in other cases activists confront the public and monitoring authorities with violations of state-imposed rules regarding heritage status, when certain state authorities assign to buildings the status of protected heritage sites, while other authorities allow them to be neglected, destroyed, or demolished. While it is impossible to resurrect victims of repression or restore lost heritage sites, public historians, art historians, and civic activists do what is still possible and necessary: they prevent the memory of atrocities and their victims from effacing. And this, as the article correctly argues, is the similarity between the projects described.

It would have allowed the article to make a stronger case for its point if it had demonstrated examples of how the notion of cultural heritage plays a defining role in the discourses of the “Last Address” and “It’s is Right Here” projects.

__________

В данной статье рассматриваются вопросы неакадемической и неправительственной работы с прошлым, весьма актуальные для современного российского гражданского общества (хотя – к сожалению для многих историков и гражданских активистов – отнюдь не столь актуальные для остального населения России). Прошлое, будь то в форме его репрезентаций или в форме его материальных остатков, часто используется в России как поле битвы за настоящее и будущее. Поэтому неудивительно, что случаи, которым уделяется особое внимание в данной статье, связаны с самыми горячими темами в истории взаимоотношений между властями и населением в России/СССР. Первые два кейса посвящены проектам, направленным на то, чтобы сделать достоянием общественности информацию о периоде государственных репрессий – информацию, которая в значительной степени неизвестна или забыта. Таким образом, они выполняют работу, которую могла бы выполнить социальная память, если бы таковая существовала. Для того чтобы представить как можно более правильную и полную информацию, эти проекты включают исследования истории отдельных людей и мест, и эта информация публикуется ими в Интернете, благодаря чему она становится доступной для русскоязычных читателей во всем мире. Если мемориальные таблички “Последнего адреса” содержат минимум информации, то комментарии на сайте проекта зачастую превосходят объемом энциклопедические статьи, а во многих случаях они содержат больше информации, чем сохранилось в памяти у людей, инициирующих установку таблички. Важно подчеркнуть, что оба проекта принципиально отказываются от критерия “значимости” или “известности” той или иной жертвы репрессий: и истории в рамках проекта “Это прямо здесь”, и таблички “Последнего адреса” рассказывают о любых людях, независимо от их известности или роли, которую они сыграли в истории страны (за исключением собственно палачей).

Напротив, третий и четвертый проекты, о которых идет речь в статье, направлены не столько на воскрешение памяти людей, убитых государством в советское время, сколько на сохранение таких объектов недвижимого культурного наследия, которые, по мнению активистов, имеют художественную ценность как произведения архитектуры или являются исторически интересными местами, связанными с особо выдающимися событиями и личностями прошлого. По иронии судьбы, иногда статус охраняемого памятника архитектуры оказывается препятствием для размещения на здании таблички “Последнего адреса”, т.е. две концепции работы с прошлым приходят в столкновение друг с другом.

В качестве теоретической основы этого небольшого исследования, располагающегося на пересечении публичной истории и критических исследований наследия, убедительно используется концепция авторизованного дискурса наследия (AHD), которую ввела австралийская исследовательница Л. Смит. В статье показано, как в одних случаях активисты оспаривают монополию государства на авторитет в выявлении и мемориализации объектов (“Последний адрес” опирается на государственную власть лишь в одном пункте: таблички устанавливаются только если человек был официально реабилитирован), а в других случаях активисты заставляют общественность и контролирующие органы обратить внимание на случаи, когда одни государственные органы присваивают зданиям статус охраняемых объектов наследия, а другие государственные инстанции попустительствуют тому, что эти объекты оказываются в запустении, разрушаются или сносятся. Хотя невозможно воскресить жертв репрессий или восстановить утраченные объекты наследия, публичные историки, искусствоведы и гражданские активисты делают то, что все еще возможно и необходимо: они предотвращают стирание памяти о злодеяниях и их жертвах. И в этом, как правильно подразумевается в статье, заключается сходство между описанными проектами.

Статья выиграла бы в убедительности, если бы в ней были приведены примеры того, как понятие культурного наследия играет определяющую роль в дискурсах проектов “Последний адрес” и “Это прямо здесь”.