Abstract: When International “Memorial” created its database of the Soviet political terror victims, it became easier to search the names of repressed relatives. But still this theme is a point of discussion only in narrow circles of historians, researches and relatives of the sufferers. The “Open list” project gives more people a chance to involve in this discussion. It let people not only to search, but to form their memory online through adding new names to endless victims list and telling us their stories on the project’s pages.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-19141

Languages: English, Russian

Советское государство хорошо знало, как справляться со своими политическими оппонентами – реальными или мнимыми. За почти 75 лет существования СССР миллионы человек были расстреляны, направлены в лагеря или в психиатрические больницы на принудительное лечение по политическим мотивам. В ходе коллективизации и сопровождавшего ее «раскулачивания» наиболее трудолюбивые крестьяне были высланы в Сибирь на спецпоселение, тысячи из них погибли по дороге или вскоре после прибытия на новое место жительства. Депортации, совершенные по национальному признаку в годы Великой Отечественной войны, стали наказанием для целых народов за военные преступления их отдельных представителей. Эти кампании навсегда изменили этническую географию всей страны.

Что мы знаем о жертвах советского террора?

Большая часть населения стала жертвами репрессий во время правления Сталина. Почти никто из них в реальности не совершал никаких «контрреволюционных преступлений» и не был коллаборационистом в годы войны. Почти все они впоследствии были реабилитированы, а их имена составили бесконечный скорбный список невинных жертв государственного террора.

Несмотря на формальное существование Концепции по сохранению памяти жертв политических репрессий, предложенной президентом РФ, сегодня эта тема является предметом дискуссии лишь в узких кругах ее исследователей и родственников жертв репрессий. Закон о реабилитации жертв политических репрессий был принят в 1991 году, но с того времени стало очевидно, что он нуждается в пересмотре и в расширении списка тех, кто подлежит реабилитации. Сам процесс реабилитации практически остановлен и проходит только на основании личных заявлений. В обществе разговор о теме советских репрессий все чаще вызывает отторжение и немотивированную агрессию в силу посредственных знаний об истории своей страны и искаженного государственного взгляда на нее. В таких условиях задача по сохранению памяти о жертвах советского террора и правдивый рассказ об одном из самых травмирующих эпизодов истории России ложится на плечи историков, исследователей и неравнодушных организаций. Лидирующая роль в этом процессе по праву принадлежит историко-просветительскому обществу «Мемориал», признанному в России «иностранным агентом». Именно «Мемориал» еще в начале 1990-х годов начал активную работу по составлению списков жертв советских политических репрессий.

«Бумажная память»

Сегодня у подавляющего большинства российских регионов есть собственные «Книги памяти». Историки, архивисты и общественные деятели создают их в сотрудничестве с ведомственными архивами. Процесс сбора и обработки информации является очень трудоемким и дорогостоящим и нередко занимает более одного года. 30 лет спустя выпуска первой книги известны имена только 20% от всех жертв советских репрессий. В первую очередь, в книги включаются имена тех, кто был приговорен к расстрелу и части направленных в исправительно-трудовые лагеря.

В каждом регионе издавались несколько томов «Книг памяти», имевшие ограниченный тираж, который почти не поступал в продажу. Книги оставались труднодоступными для всех желающих, а базы данных, ложившиеся в их основу, не публиковались в открытом доступе. В 2001 году с целью популяризации «Книг памяти» «Мемориал» начал работу по объединению их данных в единой базе. Она обновляется каждые несколько лет и на сегодняшний день содержит более трех миллионов записи. Тем не менее, бумажное издание остается символом «Книги памяти».

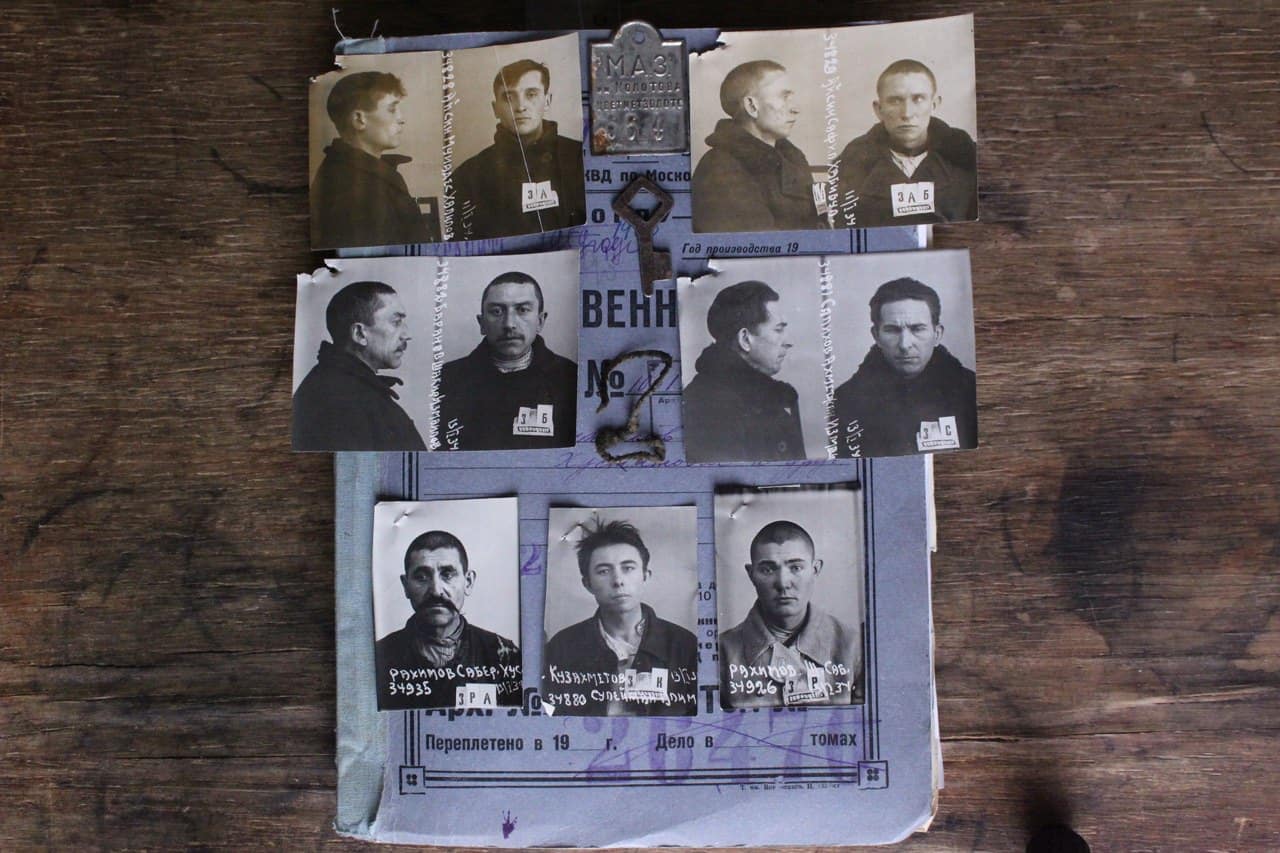

Краудсорсинг в помощь собирателям имен

В 2016 году с целью помочь «Мемориалу» в сборе имен и популяризации истории советских политических репрессий был запущен проект «Открытый список». Его главная особенность – википедийный формат, где любой зарегистрированный пользователь может добавить новое имя в список онлайн или поправить уже существующую страницу, написать биографическую заметку или опубликовать фотографии или документы репрессированного человека. С момента запуска проекта в списке появилось более 35 тысяч новых имен. Цифровой архив «Открытого списка» насчитывает более 30 тысяч фотографий и 2,5 тысяч документов. Сотни историй составляют новый исторический источник, – корпус воспоминаний, который еще ждет своего исследователя. Эти истории показывают «народное» понимание государственного террора, где господствует миф о миллионах доносов, обвинение перекладывается с организаторов на исполнителей, а семейные легенды приукрашивают и без того страшные воспоминания.

Эта электронная «Книга памяти» пополняется каждый день. «Бумага», которую «Мемориал» превратил в «цифру», обретает новое наполнение по мере того, как люди редактируют страницы жертв репрессий. Рассказывая нам их истории и делясь своими мыслями об этом, люди освобождаются от секретности, на которую их обрекла советская власть, годами сковывавшей их семьи. Таким образом люди делают огромный шаг к проработки травмы их проблемного прошлого.

«Книга памяти», рожденная в «цифре»

В 2017 году команда «Открытого списка» начала составлять собственную «Книгу памяти», посвященную репрессированным москвичам. В центральном российском регионе до сих пор нет единой книги. Созданные ранее включают в себя только имена без подробной информации о биографии и аресте или же приводят только имена тех, кто был расстрелян. Те же, кто был направлен в лагеря, чьи приговоры впоследствии были отменены, кто был направлен на принудительное лечение или привлечен по политическим мотивам без дальнейшего осуждения в основном не упомянуты в существующих списках. «Открытый список» решил закрыть этот пробел изучением самой большой московской коллекции следственных дел, которая хранится в Государственном архиве РФ в фонде 10035. Договор с архивом помог начать беспрецедентный проект по сплошной оцифровке следственных дел и созданию на их основе электронной «Книги памяти».

В составлении книги реализованы все основные принципы работы «Открытого списка», двигатель которого – краудсорсинг. Каждый день волонтеры проекта снимают следственные дела в архиве. В то же время другие волонтеры и редакторы проекта заполняют страницы репрессированных, используя шаблон по разбору следственного дела, составленный историками – сотрудниками проекта. Каждый день страницы проекта дополняются в режиме онлайн. За 4 года работы проекта названо 20 тысяч имен людей, осужденных с 1930 по 1945 год. Некоторые из них родственники репрессированных уже дополнили биографиями и материалами из личных архивов.

Составление «Книги памяти» помогает исправлять ошибки на существовавших ранее страницах, такие, как объединение на одной странице данных на полных тезок или опечатки и ошибки в справках о реабилитации, изданных Прокуратурой г. Москвы. Электронная «Книга памяти» содержит не только информацию из следственных дел, но из книг других регионов. Иногда это помогает проследить судьбу человека после первого ареста. Материалы от родственников репрессированных способствуют более глубокой источниковедческой работе со следственными делами. С ее помощью удается дополнить подчас искаженные семейные истории достоверными фактами, а иногда эти истории дополняют сухие материалы следственных дел. Такая работа с «народной» памятью и рассказ о ней в социальных сетях проекта способствуют популяризации истории советского политического террора и раскрытию роли индивидуального в каждом конкретном государственном преступлении.

_____________________

Литература

- Kurilla, Ivan. “Presentism, Politicization of History, and the New Role of the Historian in Russia.” In The Future of the Soviet Past: The Politics of History in Putin’s Russia, edited by Anton Weiss-Wendt and Nanci Adler, 29-47. Bloomington, IN.: Indiana University Press, 2021.

- Epple, Nikolay. An Inconvenient Past: Memory of the State Crimes in Russia and Other Countries. Moscow: New Literary Review, 2020.

Ссылки в Интернете

- Arsenii Roginskii and his lection about Soviet political terror https://urokiistorii.ru/articles/masshtaby-sovetskogo-terrora (last accessed 13 December 2021).

- Book of Memory of repressed Muscovites https://ru.openlist.wiki/Категория:Электронная_Книга_памяти_Москвы_и_Московской_области (last accessed 13 December 2021).

- International “Memorial” database https://base.memo.ru/ (last accessed 13 December 2021).

_____________________

Авторы фотографий

© 2021 The Author.

Рекомендация для цитирования

Мишина Екатерина Максимовна: Как оцифровать память о терроре: опыт «Открытого списка». In: Public History Weekly 9 (2021) 10, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-19141.

Редакционная ответственность

The Soviet state knew well how to handle its real or false political opponents. In almost 75 years of existence of the USSR, millions were shot, sent to labor camps or to compulsory treatment for political reasons. During the dispossession of the “kulaks”, the most workable peasants were sent to Siberia on special settlement, thousand died on the way or shortly after its end. Deportations on a national basis were a punishment for the whole nations for crimes of some of its representatives during the Great Patriotic War. After all these campaigns the whole country changed its ethnic geography forever.

Our Knowledge about Soviet Terror Victims

Most parts of terror victims got this status during Stalin’s rule. Almost every one of them never committed any “counterrevolutionary crimes” and were not collaborators during the war. Almost every one of them was subsequently rehabilitated, and their names started to compile an endless sorrow list of innocent state terror victims.

Today this theme is a point of discussion only in narrow circles of its researches and relatives of sufferers despite the formal existing of conception for the perpetuation of the memory of political terror victims suggested by the Russian President. The law on the rehabilitation of political terror victims was adopted in 1991, but since that time it became clear that the law needs to be revised and previously unrecorded categories of the repressed persons to be included in it. The process of rehabilitation itself has practically stopped and is taking place only on the basis of individual applications. In society talks about Soviet political repressions causes rejection and outright aggression more often due to mediocre knowledge of our country’s history and distorted state governmental view on it. In such conditions preservation of memory of Soviet terror victims and fair presentation of the most complicated episodes in Russian history become a fate for indifferent organizations, researchers, and historians. The main role in this process rightfully belongs to the International “Memorial”, which has “the foreign agent” status in Russia. It was “Memorial” who in the early 1990s started active work on compiling lists of Soviet terror victims.

The Memory “in Paper”

Today, majority of Russian regions have its own Books of Memory of political terror victims. Historians, archival workers, public figures compile them in collaboration with the staff of departmental archives. The process of collecting and organizing the data is very laborious and expensive and takes more than one year. 30 years after its start all issued books contain only 20% of all names of repressed persons. Primarily, they include people who were condemned to death and a part of those who were sent to labor camps.

Every region that issued Books has several volumes of them with a limited circulation. They practically did not go on sale and remained difficult to approach for everyone, and databases which were created in some regions did not publish in open access. In 2001 “Memorial” started to unite all Books data in one base to popularize their content. This database is updated every few years and nowadays includes more than three million names.

Crowdsourcing helps the Collectors

In 2016 the «Open list” project was launched to help “Memorial” in collecting names and popularizing history of Soviet political repressions. Its main feature is “Wikipedia” format, where every registered person can add new names to the list or edit already existing pages, write biographies or complement pages with photos and documents online. Since the project has run, users have added more than 35 000 new names. Today digital archive contains almost 30 000 photos and 2500 pages with documents. Hundreds of stories make up a new historical source like memoirs corpora, which is still waiting for its researcher. These stories demonstrate popular understanding of state terror with the myth of the leading role of denunciations, an accusation of not the state, but the executors, different family legends with some fact that makes already horrifying moments more dramatic.

This electronic book is supplemented every day. A paper that “Memorial” turned into digital data gains new content as far as users editing terror victims pages. Telling us the fates of their relatives and sharing their thoughts with others, people get rid of secrecy that shackled their families for years, and oblivion which the Soviet state doomed them on. That way people can make a huge step to work out their trauma from their troubled past.

Digital-born Book of Memory

In 2017 “Open list” team started to compile a new book– the electronic Book of Memory of repressed Muscovites. State’s central region still has not got a unified Book of Memory. Already existing books contain only names without information about repression or include only those who were shot. Names of terror victims sent to labor camps or to compulsory treatment, were arrested for political reasons, and had cases closed by rehabilitating causes are not mentioned in any list. “Open list” decided to solve this problem by researching one of the biggest collections of investigative cases no. 10035, which is preserved in the State archive of the Russian Federation. The agreement with archive allowed to begin an unprecedented project on partly digitalization of investigative materials and compiling list of repressed Muscovites in digital form.

Compilation of book unites all principles of “Open list” working. Crowdsourcing is like an engine of this process. Every day project’s volunteers digitize investigative cases in the archive. At the same time “Open list” editors and other volunteers fill in the book’s pages online using the template for describing the investigative case, which was created by historians working in the project. Every day new names emerge in the book’s digital pages, in four years 20 000 in total, covers people who were arrested between 1930 and 1945. Some of them have been already complemented with photos and biographies provided by relatives of repressed persons.

Compilation of book helps to correct mistakes in other already existing books such as a merge of full namesakes on one page or misprints in certificates of rehabilitation issued by Prosecution Office of Moscow. The book contains not only information from investigative cases, but also from Books of memory of other regions. Sometimes it helps to trace a person’s fate after the first repression. Materials from relatives assist in deeper source-study of investigative cases, as they fulfill formal clerical documentation with emotional facts from real-life stories, or sometimes family stories come into compliance with investigative materials. Such work with popular memory and sharing it as posts in the project’s social networks aids to popularize history of the Soviet terror and personal in every certain state crime.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Kurilla, Ivan. “Presentism, Politicization of History, and the New Role of the Historian in Russia.” In The Future of the Soviet Past: The Politics of History in Putin’s Russia, edited by Anton Weiss-Wendt and Nanci Adler, 29-47. Bloomington, IN.: Indiana University Press, 2021.

- Epple, Nikolay. An Inconvenient Past: Memory of the State Crimes in Russia and Other Countries. Moscow: New Literary Review, 2020. (In Russian)

Web Resources

- Arsenii Roginskii and his lection about Soviet political terror https://urokiistorii.ru/articles/masshtaby-sovetskogo-terrora (last accessed 13 December 2021).

- Book of Memory of repressed Muscovites https://ru.openlist.wiki/Категория:Электронная_Книга_памяти_Москвы_и_Московской_области (last accessed 13 December 2021).

- International “Memorial” database https://base.memo.ru/ (last accessed 13 December 2021).

_____________________

Image Credits

© 2021 The Author.

Recommended Citation

Mishina, Ekaterina: Making Memory of Repressions Digital. In: Public History Weekly 9 (2021) 10, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-19141.

Editorial Responsibility

Copyright © 2021 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 9 (2021) 10

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-19141

Tags: Collaboration, Culture of Remembrance (Erinnerungskultur), Digital Change (Digitaler Wandel), History Politics (Geschichtspolitik), Language: Russian, Russia (Russland)

Russian version below. To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

OPEN PEER REVIEW

A Clear Overview

Ekaterina Mishina gives a clear overview of the history and ideology of one of the most outstanding projects among the newest online databases. Such projects are changing not only the digital landscape of the Runet, but also the very conditions in which the memory about the political repressions of the Soviet era exists.

Instruments

An important function of the new databases is to facilitate access to personal and official documents and information as well as the restoration of family history. Here, an important role belongs to databases on the history of repressions (supported by Memorial or other independent institutions, by regional researchers and, which is much more rare, by official institutions), on the one hand, and projects like «Memory of the People» (https://pamyat-naroda.ru), «OBD Memorial» (https://obd-memorial.ru/), «In the Memory of Great War Heroes. 1914-1918» (https://gwar.mil.ru/heroes/), on the other. These databases were created by the Archive of the Russian Ministry of Defence in order to provide documents about those who fought in the First and Second World Wars. They contain essential information and documents which help find information about family members, as most Russian citizens have relatives who fought in the wars and/or were repressed.

An important limiting factor for use of and work on such databases continues to be the underdevelopment of national digital index systems: the authority files of the main libraries are closed, the largest indices and gazetteers are not adapted for external databases.

Communities

As Ekaterina Mishina points out, sites like the «Open List» contribute to the formation of digital communities of memory around them. These communities are not localised in one particular city and can’t, therefore, look after monuments or graves of the repressed, etc. However, their work is invaluable in terms of collecting information and publishing archival documents (often inaccessible to individual researchers). Striking examples are the community risen around the history of Dmitry Karagodin’s investigation (https://karagodin.org) and the community of the site “Personnel of the USSR State Security Bodies, 1935-1939” (https://nkvd.memo.ru/). For decades, information about individual families and settlements in Russia has been gathered at the forum of the All-Russian Genealogical Tree (https://forum.vgd.ru).

Digital transformation and new media

Digital transformation, easier access to data and emerging of digital communities lead to the fact that surviving family stories of terror and state violence find representation in new media and a wide response among a wider audience.

Based on the databases of repressed and archival research, «The Last Address» community (https://www.poslednyadres.ru) has already installed more than 1220 information signs (in over 60 cities all over the world) on the houses from which the political repressed were taken away. Each sign requires the approval of all dwellers of the house and therefore represents social consensus about the attitude to the political terror.

In recent years, the theme of repression and family memory has become central in several graphic novels, namely «The Survivors» (Gulag Museum, 2019) and «Survilo» (O. Lavrentieva, 2019). Both novels have been a milestone for Russian graphic novel art: while novels like «Maus: A Survivor’s Tale» (A. Spiegelman) or «Persepolis» (M. Satrapi) are widely known, the representation of repressions, Leningrad’s blockade and other «serious» topics of Russian history on the pages of graphic novels provoked debates. The topic of political repressions and families struggling through the Soviet era lies behind the board game “74. Board game on Soviet history» (https://74game.ru) issued in 2018. The game shows the connection between «global» and personal history and differs from many games portraying the Soviet era in a nostalgic way. The topic of political repressions is also important in new Russian documental animation. The recent cartoons «Harbin. The story of Galina Deyeva» (P. Campioni, 2019) and «I can’t add anything» (T. Stefanenko, 2021) were well received at many cartoons festivals.

The examples provided allow us to talk about the beginning of a new era in the history of memory about the 20th century and question one of the points made by Ekaterina Mishina, namely little interest in the topic of repression in society. Probably (and temporarily?), the «human rights» discourse of the topic, very popular in 1980-1990s, is becoming less and less loud. However, after decades of ignorance, continuing lack of documents and limited access to the archives, society is gradually beginning to accept and process this topic as part both of personal experience and community history. This certainly requires a new language, new tools, and new approaches.

_________

В своей статье Екатерина Мишина прекрасно показала историю и идеологию одного из наиболее ярких проектов в плеяде новых баз данных. Такие проекты (некоторые существуют десятилетиями, некоторые появились в последние несколько лет)

меняют не только цифровой ландшафт рунета, но и сами условия, в которых сейчас существует память о репрессиях советской эпохи.

# инструменты

Важной функцией новых баз данных стало облегчение доступа к документам и восстановлении истории семьи. Большую роль здесь играют как базы по истории репрессий, так и проекты вроде Памяти народа (https://pamyat-naroda.ru), ОБД Мемориал (https://obd-memorial.ru/), 1914-1918 (https://gwar.mil.ru/heroes/). Эти базы сделаны архивом Министерства обороны для представления документов о воевавших в Первой и Второй мировой войне и содержат важнейшую информацию для поиска сведений о родственниках.

Важным сдерживающим фактором для развития и использования таких баз до сих пор остаётся неразвитость национальных систем цифровых указателей: авторитетные файлы главных библиотек закрыты для пользователей, крупнейшие справочники не приспособлены для использования сторонними базами данных.

# сообщества

Как отмечала Екатерина Мишина, сайты вроде «Открытого списка» способствуют формированию цифровых сообществ памяти вокруг них. Новые сообщества не локализуются в одном городе, поэтому, например, не заняты уходом за памятниками или могилами репрессированных. Однако их работа бесценна в том, что касается сбора информации и публикации архивных документов (зачастую недоступных индивидуальным исследователям). Яркими примерами может послужить сообщество, сложившееся вокруг истории расследования Дмитрия Карагодина (https://karagodin.org), или сообщество сайта «Кадровый состав органов государственной безопасности СССР, 1935-1939» (https://nkvd.memo.ru/). Десятилетиями информация об отдельных семьях и населенных пунктах России накапливается на форуме Всероссийского генеалогического древа (forum.vgd.ru).

# цифровая трансформация и новые медиа

Цифровая трансформация, облегчение доступа к данным ведут к тому, что сохранившиеся семейные истории о терроре и государственном насилии находят репрезентации в новых медиа и широкий отклик во все новых сегментах аудитории.

Основываясь на базах данных репрессированных и архивных исследованиях, сообщество «Последний адрес» (https://www.poslednyadres.ru) установило уже более 1220 информационных знаков (более 60 городов мира) на домах, откуда забирали политических репрессированных. В последние годы вышло несколько комиксов, где тема репрессий и семейной памяти стала центральной — это «Вы-жившие» (Музей ГУЛАГа), «Сурвило» (О. Лаврентьева). Тема политических репрессий является одним из драйверов настольной игры «74. Настольная игра по советской истории» (74game.ru). Эмоциональными и рефлексивными стали высказывания режиссеров мультфильмов «Харбин. История Галины Деевой» (П. Кампиони, 2019) и «Дополнить ничего не могу» (Т. Стефаненко, 2021).

Всё это, как кажется, позволяет говорить о начинающейся новой эпохе в истории памяти о 20 веке и ставит вопрос к одному из тезисов Е. Мишиной – о невостребованности темы репрессий в обществе. Наверное, все менее громко звучит характерное для 1980-1990-х “правозащитное” прочтение темы. Однако общество начинает постепенно принимать и перерабатывать эту тему как часть личной, семейной и городской истории. Это, безусловно, требует нового языка, новых инструментов и новых подходов.