Abstract:

There is agreement amongst media commentators that the spread of so-called fake news poses a serious threat to democratic society, and as history educators, we have an obligation to help stem the rising tide of misinformation. Until now, not many have accepted the challenge, perhaps from a misconception of “fake news” as a modern, post-Internet phenomenon. But disinformation has been with us for millennia, and historical examples may provide the key to developing a critical sense among students.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-19199

Languages: English

During the catastrophic floods that swept across Germany in July 2021, the waters breached a hydroelectric dam on the river Wupper, putting thousands of lives at risk. In the video clip shared on Telegram, more than 30,000 users could see for themselves the water cascading over the edge and carving great gashes through the embankment. Except that it never happened. The river was not the Wupper and the video did not show a crumbling hydroelectric dam, but a flooded lignite quarry.[1]

Can fake news be stopped – and how?

Fake news, defined by the Cambridge English Dictionary as “false stories that appear to be news, spread on the internet or using other media, usually created to influence political views or as a joke” pose a challenge to modern open, democratic societies. Fake news may cause panic, it can determine the outcome of elections, it can cost lives. In January 2021, armed supporters of Donald Trump stormed the U.S. capitol in Washington. Five persons died during the fighting, which was fueled by claims that the presidential election had been “stolen”. Many more lives will be lost among those who refuse to let themselves be vaccinated against Covid-19 from fear of being injected with a microchip.

The seemingly simple solution is to stop fake news at its source by removing fake information from websites and excluding users who use social media platforms to spread disinformation (a well-known example is then-US President Trump, who was permanently barred from Twitter). But if the aim is to protect democracy, then censorship is not the best way forward and in a globalized world, governments have no means to check the flow of misinformation across their borders.

Another approach is to tackle the problem at the receiving end. A fake news item spreads like wildfire because social media users believe it and pass it on to others. If internet users can learn to spot fake news, they will not pass it on, and it will eventually die out. Part of the solution is to improve students’ “media literacy” by teaching them to choose reliable websites, for instance government agencies and universities, in preference to sites sponsored by corporations, political parties or religious groups. But uncritical belief in government institutions is not good for democracy either and in any case, most recipients of fake news do not obtain their information directly from a website but indirectly from retweets on social media. Students must be empowered to judge for themselves and spot dubious arguments and spurious documentation when they encounter them.

Fake news is not always new

As history educators, we should be among the first to take up the challenge. After all, the judicious analysis and evaluation of sources is central to the historian’s craft. And not all fake news is “news” in the usual sense of the word, i.e. reports of recent or current events. That “Barack Obama is a Muslim” is a statement about the present, but “Barack Obama was born outside the United States” (which, if true would make him ineligible for the US presidency) is a statement about the past; it is fake history.

An early example of fake history is the Book of Daniel in the Old Testament, which tells the story of the Jewish prophet Daniel, astrologer to Babylon’s king Nebuchadnezzar in the sixth century BC. In the book, Daniel predicts the fall of the Persian empire, the advent of a hero-king (Alexander the Great) and many other events down to the Jewish rebellion in the 160s BC. For the rebels, it was encouraging to know that events of their own time had been foreseen by Daniel four centuries previously, clear proof that the decline of the Seleucid empire formed part of a divine plan and that God was on their side.

Strangely enough, the Book of Daniel is far less reliable when describing events of the prophet’s own time, the sixth century BC, and most Biblical researchers agree that the book as we now have it is a product of the second century. The author-compiler took some old stories about a sixth-century prophet named Daniel and added a series of “prophecies” about events which had already taken place at the time of writing.

Historical fakes abound. Many are crude forgeries and soon unmasked: the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the “Hitler diaries” of Konrad Kujau or the Kensington runestone which supposedly documents a Scandinavian expedition to Minnesota in the 14th century.

The Historia Augusta, a collection of Roman biographies by six different authors, had a longer afterlife and was used as a source text by generations of historians. Even the nestor of German source criticism, Leopold von Ranke (1795-1886) was taken in and praised the source value of the History in his Weltgeschichte, published 1883. Six years later, another German, Hermann Dessau (1856-1931), demonstrated that the entire collection was the work of one author, not six, and completed at least half a century after its ostensible date.

In the twelfth century a Welsh monk, Geoffrey of Monmouth, composed a History of the kings of Britain. In the Preface, he explains that he did not write it himself but translated “a very ancient book in the British tongue” (i.e., Welsh) into Latin. No one apart from Geoffrey himself saw the book, and there is no reason to believe that it ever existed. Part of his History is a hotchpotch of material taken from other writers, other parts – such as the stories of King Arthur and his court magician Merlin – are clearly the product of Geoffrey’s own imagination. Though its veracity was questioned from an early date, Geoffrey’s work was still being read and quoted as late as the sixteenth century, and his stories about king Arthur live on to this day.

Faking it – why?

Creating the Historia Augusta, the Hitler diaries or Geoffrey’s History clearly involved a lot of work. Why did the forger go to such trouble; what were his (or her) motives? If we look at other classes of historical forgery – artworks, coins, archaeological artefacts – money and the desire for recognition are the two most obvious motives. Money was no doubt uppermost in the mind of Konrad Kujau, who received more than 2 million DM for his “Hitler” diaries. Other forgers, however, did not become as rich: the owner of the Kensington runestone was offered five dollars for his “find”. As for recognition, the art forger may derive satisfaction from seeing his work accepted as a genuine Picasso or Rembrandt, but the text forger cannot achieve recognition without unmasking himself.

One thread running through many historical forgeries is an underlying sense of frustration. The forger and his circle find themselves in circumstances from which they are unable to escape. As a Welshman, Geoffrey was frustrated at the loss of Celtic Britain to Germanic invaders; as a pagan, the author-forger of the Historia Augusta was frustrated that Christianity was being imposed on the subjects of the Roman Empire. To Scandinavian-Americans, it seemed insufferable that an Italian should get all the credit for discovering America when Vikings had crossed the Atlantic five hundred years before Columbus. And some Americans found it so unbearable that Biden should be inaugurated as president when they believed, incorrectly, that Trump had won the election that they determined to set things right. While it is a truism that “history is written by the victors”, it is rewritten by the losers.

Just as past creators of historical forgeries found themselves facing formidable adversaries (the Seleucid Empire, Christianity, the Anglo-Saxon invaders), present-day creators of fake news often target powerful persons or institutions: Bill Gates, George Soros, “big government”, the medical industry or ‘big pharma’, the “deep state”.

A third point in common is that forged historical narratives, like fake news, gain credence because readers want them to be true. The Jews wanted the fall of the Seleucid Empire to be part of God’s plan; the Welsh wanted a glorious Celtic past under king Arthur, just as the followers of Donald Trump wanted him to be the rightful president.

Lessons from the past

That a source text is forged does not mean that it is of no interest to historians. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion are an important source for nineteenth-century anti-Semitism and with care, it is possible to extract bits and pieces of authentic history from the tangled skein of fact and fiction in the Historia Augusta or the History of the Kings of Britain. Even more important in the present context is the didactic potential of historical forgeries in the history classroom. By studying a historical hoax, students can learn to analyse arguments and spot some of the typical techniques used by purveyors of misinformation.

For classroom use, the Kensington runestone offers a particularly good case study. Hjalmar Rued Holand (1872-1963), a Norwegian-American writer, devoted much of his life and several books to proving that the runic inscription was genuine and in Westward from Vinland (1940) he collected the arguments in its favour. In the book, Holand employs argumentative techniques familiar to observers of the fake news phenomenon, such as cherry-picking from the scientific literature, selectively amassing peripheral or circumstantial “evidence” that appears to support the theory of a Norse expedition while ignoring evidence against it and shifting the burden of proof on to his critics: “No valid evidence to show that the inscription is a forgery has been presented”.[2]

Holand also took the stone on a tour of European universities and museums. Most of the experts he consulted rejected it as a fake, but a few academics went against the majority view and declared it authentic – just as today’s news fakers will often find a maverick academic to support their claims that quinine (medication used to treat malaria) is effective against Covid-19, that 5G networks cause cancer, or that the moon landing of 1969 never took place. A small circle of loyalists continues to believe in the authenticity of the Kensington runestone, which even has its own museum.

Analysing a historical forgery as a classroom case, students will learn to see through dubious arguments, appreciate the value of scientific documentation and understand why some people continue to insist that a forgery is authentic. At the end of their quest, they will be better equipped to deal with the flood of fake news and misinformation flowing through their smartphones.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Roland Bernhard, “Fake News, Conspiracy Theories and Textbooks”, Public History Weekly 2021, no. 9 (March 2021), DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17608.

- Gordon Pennycook and David G. Rand, “The Psychology of Fake News”, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, vol. 25, no. 5 (May 2021), DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.02.007.

- Hjalmar Rued Holand, Westward from Vinland: An Account of Norse Discoveries and Explorations in America, 982-1362 (New York: Duell, Sloane & Pierce, 1940).

Web Resources

- European Parliament, “The impact of disinformation on democratic processes”, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/653635/EXPO_STU(2021)653635_EN.pdf (last accessed 8 Dec 2021).

- World Health Organization, “Fighting misinformation in the time of COVID-19, one click at a time”, https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/fighting-misinformation-in-the-time-of-covid-19-one-click-at-a-time (last accessed 8 Dec 2021).

- Website of the Runestone Museum (Alexandria, Minnesota), https://runestonemuseum.org/ (last accessed 8 Dec 2021).

_____________________

[1] CORRECTIV, “Faktencheck. Hochwasser: Nein, dieses Video zeigt nicht den Bruch einer Talsperre bei Wuppertal”, https://correctiv.org/aktuelles/2021/07/16/hochwasser-nein-dieses-video-zeigt-nicht-den-bruch-einer-talsperre-bei-wuppertal/ (last accessed 8 Dec 2021).

[2] Hjalmar Rued Holand, Westward from Vinland: An Account of Norse Discoveries and Explorations in America, 982-1362 (New York: Duell, Sloane & Pierce, 1940), 252.

_____________________

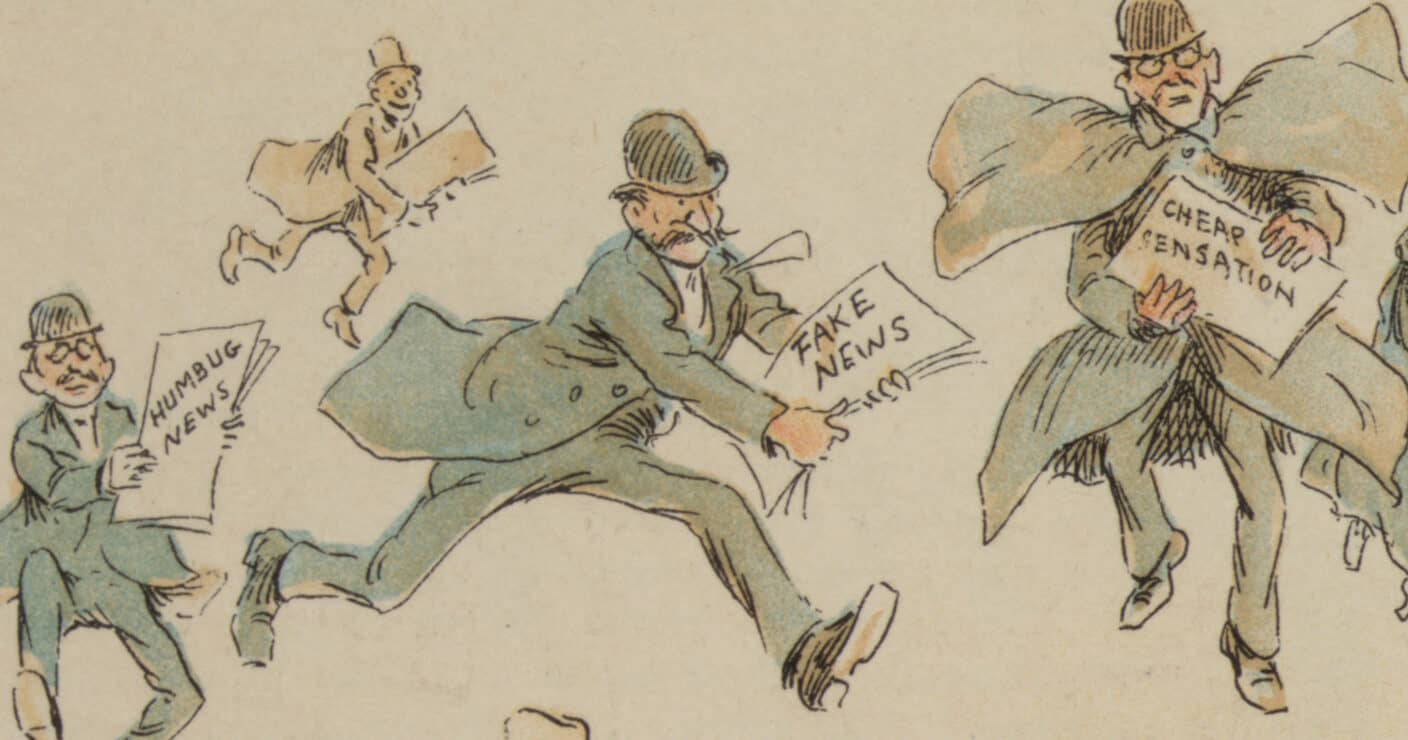

Image Credits

Public Domain via Flickr.

Recommended Citation

Bekker-Nielsen, Tønnes: Fake News from the Past – Lessons For the Future. In: Public History Weekly 9 (2021) 10, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-19199.

Editorial Responsibility

Copyright © 2021 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 9 (2021) 10

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-19199

Tags: Civics Education (Politische Bildung), Digital Change (Digitaler Wandel), Fake News, Speakerscorner

To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

OPEN PEER REVIEW

Conceptual Vagueness

In his text, the author takes on a phenomenon that is probably associated with the first years of the 45th U.S. President Donald J. Trump’s term in office like few others: “fake news,” used by Trump primarily as a fighting term to defame critical media. These media, first and foremost the New York Times or CNN, in turn used the term to attack Trump himself and his “alternative facts.” The central claim of the article is specifically to discuss how we, as historians and as teachers of history, can deal with this seemingly topical phenomenon. As is so often the case, the author explains that a supposedly particularly recent phenomenon is not so new at all, but that a multitude of examples of it can be found in history. Unfortunately, in this endeavor, the article remains at a somewhat superficial level. This already starts with the definition of “fake news” used in the introduction, which is borrowed from a dictionary.

While one can easily go along with the first part of the definition, that fake news is news that is “usually created to influence political views”, the following words “or as a joke” at the end of the definition should actually make us wonder. This would mean that even popular satirical magazines such as the German “Postillion” would spread fake news. Whether such a broad definition of “fake news” really helps is more than questionable. The very abitrare selection of historical examples of alleged “fake news” also raises numerous questions – such as whether, for example, the fake Hitler diaries, which the German “Stern” fell for, actually belong in the same category as the very claim by Donald Trump that the Democrats stole the election. Here, the article partly does not even live up to its own very basal definition of “fake news.”

In general, the article has weaknesses, especially on a theoretical meta-level – for example, it does not reflect on who actually determines what is and what is not “fake news” – a process that, as the example of Trump used in the introduction of this review shows, is often the subject of sometimes fierce social debates. Once again, it seems as if the historian, as the guardian of truth, is the one who governs what is true, right, and reasonable and what is not.

The article would have benefited if significantly more recent research literature had been considered. Few other phenomena have seen as many papers published in recent years – especially since the beginning of the current “Covid-pandemic” – as the conglomerate of “fake news,” “misinformation,” and “conspiracy theories.” The author could probably have spared himself some theoretical fuzziness if he had better situated his article within these ongoing research debates. For example, the central question of what distinguishes these terms from each other – because in some passages in the article it seems as if everything is actually the same and the terms can be used synonymously.

This conceptual vagueness also applies to the question of how to deal with these phenomena. Above all, the uncritical use of the term “censorship” once again raises eyebrows: Is the decision of private companies, such as Facebook, Twitter and others, not to publish certain content or to exclude certain people from using their services really “censorship,” i.e., state control or restriction of freedom of speech?

Towards the end of the article, the idea of letting schoolchildren and students work on source and media competence using the example of historical “fake news” – the term “forgeries” would probably be better. In this part aimed at educational purposes, too, the wheel is not reinvented, but at least it is rolling better than in other parts of the article.

To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

Conspiracy Theories in History Classes

The author describes a topic that currently clearly meets with great resonance in the media, but also in public history and history didactics.

As already mentioned by Martin Tschiggerl, it also strikes me that the terms “fake news”, “conspiracy theories” and “alternative facts” appear side by side in the article without being more precisely differentiated or distinguished from each other. Thus, I would categorize some of the examples described by the author as “fake news” not merely as “false stories that appear to be news,” but as elements or condensates of conspiracy theories. I use the term conspiracy theories here rather than “conspiracy myths,” “conspiracy ideologies,” or “conspiracy narratives” as a working term, as is often suggested in the German-speaking world, assuming a pejorative reading of this term. In my opinion, conspiracy theories pose different challenges to history didacticians than “fake news.”

Conspiracy theories serve several functions.[1] For example, they convey a sense of belonging (identity function) to a group or simply to the good, and can develop a religious dimension in the process. In addition, they are used as a cognitive tool that allows a reduction of complexity. They can also be used intentionally as a manipulation tool to create an image of the enemy or a basis of legitimacy for claims to power and discriminatory action against said enemies. Moreover, lucrative business is being done with conspiracy theories, especially nowadays.[2]

The causes[3] for conspiracy belief are manifold and not only due to the “non-recognition” of false facts. Psychological factors (although a pathologizing approach alone does not do justice to the subject, of course), social factors (e.g., crisis theory [4]), and political factors all play a role in the adoption of conspiracy theory beliefs. Most often, it is a combination of these factors that leads to belief in a threatening conspiracy. Times of crisis are particularly dangerous, because they also trigger crises of confidence and are accompanied by a feeling of alienation, powerlessness and disadvantage in many people.[5] Or, as the author aptly states for the production of historical forgeries, “an underlying feeling of frustration.”

As historians and history educators or history didacticians, we can do little to counteract many of these causes and factors. The suggestion to equip the addressees of such narratives with media literacy is certainly one possibility. If young people learn to recognize and use reliable sources as such, it will be easier for them to recognize fake news from dubious websites and channels as such and, as desired by the author, to rather obtain their information from “reliable websites, e.g., of government agencies and universities.” In the case of conspiracy theories, however, this approach may fall short, because it is precisely the state and its institutions that are often portrayed by conspiracy theorists as the enemy and spreaders of false information.[6] Facts contradicting the conviction are usually categorically rejected and dismissed as originating from conspirators or the ignorant. Conspiracy theories also often immunize themselves against falsification by constantly adding new elements to explain away contrary evidence.

One way to counter conspiracy beliefs might be to make this very problem a topic. For example, history classes could examine historical narratives with conspiracy theories and the epistemological processes that underlie them. In my opinion, education about the causes and functioning of conspiracy theories would be an important supplement to learning media literacy.

________

[1] See Pfahl-Traughber, 2002 S. 37- 39; and also Seidler, 2016, S. 58/59

[2] See Butter, Caumanns, Grewe, Großmann, & Kuber, 2020, S. 18

[3] See S. 10/11; Götz-Votteler & Hespers, 2019, S, 39; and also Anton, Schetsche, & Walter, Konspiration. Soziologie des Verschwörungsdenkens, 2014

[4] See Seidler, 2016, S. 47

[5] See Götz-Votteler & Hespers, 2019, S.47-58; and also Seidler, 2016

[6] See Lanius, 2021, S 195

Sources

– Anton, A., Schetsche, M., & Walter, M. (2014). Konspiration. Soziologie des Verschwörungsdenkens. Wiesbaden: SpringerVS.

– Butter, M., Caumanns, U., Grewe, B.-S., Großmann, J., & Kuber, J. (2020). Verschwörungsdenken in Geschichte und Gegenwart zur Einführung. Im Dialog. Beiträge aus der Akademie der Diözese Rottenburg-Stuttgart, 5-24.

– Götz-Votteler, K., & Hespers, S. (2019). Alternative Wirklichkeiten? Wie Fake News und Verschwörungsteorien funktionieren und warum sie Aktualität haben. Bielefld: transcript.

– Lanius, D. (2021). Wie sollen Lehrende mit Fake News und Verschwörungstheorien im Unterricht umgehen? In J. Drerup, M. Zulaica y Mugica, & D. Yacek , Dürfen Lehrer ihre Meinung sagen? Demokratische Bildung und die Kontroverse über Kontroversitätsgebote (S. 188-205). Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer.

– Pfahl-Traughber, A. (2002). “Bausteine” zu einer Theorie über “Verschwörungstheorien”: Definitionen, Erscheinungsformen, Funktionen und Ursachen. In H. Reinalter, Verschwörungstheorien. Theorie – Geschichte – Wirkung (S. 30-44). Studienverlag.

– Seidler, J. D. (2016). Die Verschwörung der Massenmedien. Eine Kulturgeschichte vom Buchhändler-Komplott bis zur Lügenpresse. Bielefeld: transcript.