Abstract:

Important criticisms of the Western classification of periods and their unreflected transposition to other regions of the world could be complemented by another perspective: Arab ‘own’ epochal classifications, designations and conceptions, derived from both historical sciences and the public culture of memory and history – for example in museums. The consideration of Arab positions in the debate on conceptions of history leads to further differentiations, which above all concern the relationship between ‘Western’ and ‘Arab’ participation in the use and shaping of the concept of the so called Middle Ages. The article focusses on the broader field of the culture of memory and history culture (public history) and discusses on the example of the Louvre Abu Dhabi perspectives on ‘Middle Ages’ in museums in the Arab Golf region.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2020-16559

Languages: Arabic, English, German

ناقش توماس باور مفهوم “العصور الوسطى الإسلامية” قائلاً بأنه لم يكن يومًا موجودًا: فهو مفهوم “غير دقيق”، [1] ويؤدي إلى “استنتاجات غير صحيحة” [2] و “يتركّز أساسًا في أوروبا”. [3] ويمكن استكمال هذا النقد الهام للتصنيف الغربي للفترات وانتقالها غير المنعكس إلى مناطق العالم الأخرى بمنظور آخر، ألا وهو التصنيفات والتسميات والمفاهيم المختلفة للحقبات العربية المستمدة من العلوم التاريخية والثقافة العامة للذاكرة والتاريخ – على سبيل المثال، في المتاحف. ويؤدي النظر في المواقف العربية من النقاش حول تصنيف الحقبات ومفاهيم التاريخ إلى مزيد من التمايز، ولا سيّما على مستوى العلاقة بين الاستخدامات “الغربية” و “العربية” وتشكيل مفهوم ما يسمى بالعصور الوسطى.

ماذا تقصد العصور الوسطى؟

من ناحية أخرى، ينبغي النظر إلى الجانب السلبي والاستيلائي والاستبعادي للتصنيفات التاريخية جنبًا إلى جنب مع مظاهر تمثيل الذات وتصوّر الذات وتأكيد الهوية العربية في أفكار تتمحور حول “العصور الوسطى” التاريخية الخاصة بها، إذ لا تعتمد دائمًا المعايير الغربية لتقسيم الحقبات التاريخية من جانب واحد أو تؤخذ كما هي “من الغرب” وتتطبق على الماضي العربي. فالعلماء والمثقّفون العرب ومختلف العاملين في المجال الثقافي العربي، سواء في الجامعات أو في المتاحف، يساهمون في تحديد هذه المعايير، بصورة محدّدة مرتبطة بالزمان والسياق، وغالبًا ما يكون ذلك من خلال عملية تبادل مع الأفكار الغربية.

ويتم إثراء “العصور الوسطى” بطرق مختلفة في هذه العملية: ففي القرن التاسع عشر، على سبيل المثال، حدد المحافظون الدوليون والمصريون “العصور الوسطى” بالمعنى السني-المملوكي للعاصمة القاهرة وصاغوا تعريف “العصور الوسطى” في سبيل المصلحة الوطنية ضد الحكم العثماني، في حين أن ذكرى الحكم الشيعي-الفاطمي، الذي كان تأسيس مدينة القاهرة مدينًا له، كان بالكاد مرئيًا في معالم المدينة.

إن حصر مفهوم “العصور الوسطى” بسلالة معينة، وما تبعه من عواقب واضحة على المدى الطويل لاسترداد مدينة القاهرة، ليس مجرّد عملية نقل عن الغرب. فقد كان أيضًا في مصلحة مصر والمصريين الذين عملوا على ترسيخ هذا المفهوم. واليوم، يعمل القيمون على المتاحف السورية [5] والمؤرخون العراقيون [6] أو مؤرخو الأسر المالكة الحاكمة في الخليج العربي [7]، على تصنيف حقبات تاريخهم الخاص بصورة مختلفة. فبدلاً من تحديد حقبة واحدة يطلق عليها “العصور الوسطى” وهي عبارة نقلت من “الغرب”، تتعايش عدة “عصور وسطى” من وجهة النظر العربية وفي تفكير العلماء والعاملين في مجال الثقافة. ويتماشى ذلك مع المصطلح العربي “للعصور الوسطى” الذي يستخدم في صيغة الجمع. لذلك نرى أنّ هناك ثمّة مقاومة لعملية نقل، زمنية وثقافية أحادية، لمفهوم التطور الغربي للتاريخ الذي يؤدي إلى الحداثة. ويتيح ذلك للعالم “الغربي” استخدام الدراية والمعرفة الأكاديمية بصورة منفتحة، مع مراعاة العلاقات المتداخلة المعقدة بين الأصل والمصالح والاستخدام، وبالتالي الإنتاجية الثقافية التي يعرف الجانب العربي كيف يؤكّد من خلالها استقلاليته ومصلحته الذاتية.

لا تركز الملاحظات التالية على العلوم التاريخية في الجامعات العربية بالمعنى الضيق، بل على المجال الأوسع لثقافة الذاكرة وثقافة التاريخ (التاريخ العام). وتضمّ وسائل الإعلام البارزة التي تتناول الإنتاجية الثقافية في المجال الأكاديمي غير الحصري للتاريخ العام، على سبيل المثال، متاحفًا تأسست حديثًا في دول الخليج العربي؛ سواء كان متحف قطر الوطني أو متحف الشارقة للحضارة الإسلامية [8] أو متحف اللوفر أبو ظبي. ورغم أن المتاحف تعتبر وسائط ثقافية نشأت في العالم الغربي، إلا أنها تستخدم هنا “كخطوة رئيسية للدبلوماسية الثقافية وكمثال على مؤسسة إقليمية في عالم معولم “. [9] في دول الخليج العربي في القرن الحادي والعشرين، حيث يتجاوز عدد العمال المهاجرين من جميع أنحاء العالم عدد السكان المحليين بأضعاف، تُقدَّم المتاحف على أنها “مراكز ثقافية عالمية، ليس فقط داخل العالم العربي ولكن أيضًا في علاقتها مع الغرب “[10] والأجزاء الشرقية والجنوبية الأخرى من العالم.

ونظرًا لكون هذه المتاحف تعتبر “مراكز عالمية”، فهي تقدم لزوارها نظرة جديدة وتحفًا وأعمالًا فنيّة تاريخية لا تقتصر على تاريخ منطقتهم العربية فحسب، بل تمتدّ على نطاق عالمي. ويتفرّج السكان المحليون والزوار من مختلف أنحاء العالم على المعروضات، سواء كانوا سائحين أو من الطبقة المتوسطة العالمية أو المحلية متعددة الثقافات.

دائما محور بين الشرق والغرب

“تأمل جوهر الإنسانيّة بعيون التاريخ” هو الشعار الذي يستخدمه متحف اللوفر أبو ظبي، الذي فتح أبوابه العام 2017، للإعلان عن معارضه. وعلى الرغم من أن المتحف نشأ نتيجة مشروع مشترك عربي فرنسي، إلا إن مفهومه الأساسي هو أكثر بكثير من مجرد فرع للمتحف الباريسي الشهير، فهو يتمتع بهويته الخاصة، باعتباره “متحفًا عالميًا يروي القصص التي وحّدت البشر متخطيّة حدود الزمان والمكان”.

بهذه العبارات أوجز معالي محمد خليفة المبارك رئيس دائرة الثقافة والسياحة – أبو ظبي، البعد التاريخي لبرامج المتحف الذي يُظهر التصور الذاتي للإمارة على أنها “مكان ترحيب وجسر بين مختلف الثقافات والأديان” في العالم. وتهدف التحف والأعمال التي يحتضنها متحف اللوفر بين جدرانه إلى نقل الأفكار التي تؤكد بأن المنطقة لطالما كانت نقطة تلاق بين الشرق والغرب، حتى في الماضي. ومن الضروري اليوم نسج روابط عالمية بين التاريخ والثقافة، بالتالي يشكّل متحف اللوفر أبو ظبي “الآن هذا العالم المترابط”. [11] يقدّم المتحف نفسه كمتحف عالمي [12] مخصص لهذا الغرض، على الأقل بفضل موقعه الجغرافي. وبحسب سيف سعيد غباش، المدير العام لدائرة الثقافة والسياحة، إن موقع [متحف اللوفر أبو ظبي] مميز في الإمارة. إلى ذلك، كانت المنطقة ولا تزال تتميز بموقع فريد يعزز عمليات التواصل والتبادل؛ فمركزها، وفقًا للتصور الذاتي البرامجي للإمارة، هو اليوم أبو ظبي. بالتالي يشكل موقع متحف اللوفر أبو ظبي امتيازًا لمتحف بارز في القرن الحادي والعشرين ذي أفق عالمي: “يقع المتحف جغرافيًا وفكريًا على مفترق الطرق بين الشرق والغرب”.

إلى ذلل، شكّلت المنطقة لعدّة قرون نقطة مهمة على طريق الحرير، الذي كان يربط شبه الجزيرة العربية مع آسيا وأوروبا والقرن الأفريقيّ. غير أنّ طريق الحرير لم يكن مجرد طريق لتبادل السلع، بل أتاح أيضًا تبادل المهارات والأفكار الجديدة. وفي السوق العالمية اليوم، أصبحت أبو ظبي مجددًا في قلب شبكة قوية من العلاقات الاقتصادية والثقافية. تاليًا، يجمع متحف اللوفر أبو ظبي بين هذه الروابط التاريخية والمعاصرة عبر الثقافات العالمية، فكانت النتيجة متحفًا عالميًّا للقرن الحادي والعشرين “. [13]

من ناحية أخرى، عرف التاريخ الألماني أيضًا، حتى وقت قريب، حالات إشكالية للخيال من العصور الوسطى. غير أنّ هذه التمثيلات العربية لماضي منطقة الخليج ليست خيالًا تاريخيًا، بل هي فكرة تتفق مع الخبرة والمعرفة العربية للعالم في ذلك الوقت وتستند إلى علاقات العرب الخاصة.

تُقدّم “العصور الوسطى” في متحف اللوفر أبو ظبي كفترة من المركزية العالمية والتعددية الثقافية المنتجة وتبادل المعرفة والتعايش والتنقل المكثف والتواصل بين الأديان. وتتماشى هذه المقاربة مع أبحاث حول التاريخ عبر الثقافات التي تتبعها دراسات العصور الوسطى في ألمانيا والدول الغربية الأخرى لمدة عقدين تقريبًا. [14] لكن إذا افترضنا أن اتجاهات الأبحاث الغربية في دراسات العصور الوسطى قد نُقلت فقط بهدف تصميم متحف اللوفر أبو ظبي دون النظر إلى مصالح المبادرين الإماراتيين الخاصة، فسيكون افتراضنا متحيزًا. فالسرد التاريخي للإنتاجية من خلال العلاقات الثقافية، وللشبكات العالمية حيث لطالما احتلت منطقة الخليج العربي موقعًا جغرافيًا هامًّا، يتوافق أيضًا مع الأجندات السياسية الأساسية الحالية في الإمارات العربية المتحدة.

يُمكن أن يُفهم هذا النهج أيضًا على أنه يقدم الهوية الثقافية في مجتمع يوازن بين التقليد والحداثة، من بين أمور أخرى، في ظلّ تعايش الأقليات المحلية والعمال المهاجرين المتعددي الثقافات. وبما أنّ البلاد تواجه تحديات بفعل موقعها العالمي وتثبيت هويتها الداخلية في مجتمع مطّرد التغيّر على مستوى الأديان والثقافات والأعراق المتعددة – حيث تشكل النخبة العربية الإسلامية الحاكمة في الإمارات أقلية، ولكن حيث لا يزال يلعب الدين والتقاليد دورًا حاسمًا- ، يستخدم مثال المتحف النابع من الثقافة الغربية خصيصًا لأبو ظبي اليوم “كأداة في بناء الأمة من خلال إضفاء الشرعية على الأسرة الحاكمة وسرد رواية تاريخية متسقة، وأخيرًا، كوسيلة للعلامة التجارية للوطن ولاكتساب قوة عالمية رمزية من خلال النفاذ إلى رأس المال الثقافي “. [15]

عالم متحرك

يصبح التسلسل الزمني لهذا “السرد التاريخي المتّسق” [16] العمود الفقري للمعرض حيث يجوب الزوار عالم العصور القديمة، لينتقلوا بعدها إلى الإمبراطوريات القديمة، ثمّ يصلون إلى صالات العرض التي تقدم عهودًا تمتدّ من العصور الوسطى إلى عصر النهضة. هذه الصالات مخصصة لأديان العالم دون التركيز على أي منها على وجه الخصوص: البوذية والمسيحية واليهودية والإسلام والهندوسية والكونفوشيوسية والطاوية. أما النقطة المحورية الثانية فهي طرق التجارة مثل طرق الحرير والفخار، والتواصل بين الشرق والغرب عبر البرّ والبحر على طول الطريق وصولا إلى البحر الأبيض المتوسط والمحيط الأطلسي، وأخيرًا، العلم والتكنولوجيا في عمليات التبادل والمفاهيم العالمية واستخدام أمثلة الهندسة ورسم الخرائط والتواصل متعدد اللغات في المحاكم وأساليب الحياة المختلفة.

يشكّل التواصل والتنقل والتبادل الثقافي محور عالم في حركيّة مطّردة. ويسهم العرض المتكرر لثلاث قطع أثرية فردية متزامنة إلى حد ما من أصل ثقافي وديني مختلف تشير إلى بعضها البعض موضوعيًا، في إضفاء سمة هيكلية للمعرض. لا يضمّ المتحف أي توجه غربي أحادي الجانب. فالمعروضات من الصين أو المكسيك أو الهند أو أوروبا مهمة بالقدر نفسه في الفترة الممتدة بين العصور القديمة وفجر الحداثة، وهي تخصّص أيضًا لبعضها البعض.

غير أنّ موقع دولة الإمارات العربية المتحدة في “الوسط” بين الجنوب والشمال والغرب والشرق يظل حاسماً من هذا المنظور. فالصراعات والحروب، والتنافر والعداء يُصار إلى تجاهلها إلى حد كبير. وإذا ذكرت نزاعات شبيهة بالحروب، كما هو الحال في الحروب الصليبية، يُعاد تفسيرها بطريقة مبتكرة على أنها حدثت بهدف التوسّع وتكثيف التواصل، أو مثلا لإرساء علاقات تجارية: “بعيدًا عن النزاع المسلح، اتّخذت حقبة الحروب الصليبية وتأسيس دول الفرنجة القصيرة العمر في بلاد الشام، شكلاً ملموسًا على مستوى تعزيز التجارة بين الغرب اللاتيني والشرق الإسلامي “. [17]

يمكن للزوار، سواء كانوا إماراتيين أو سائحين أو عمال مهاجرين من الطبقة المتوسطة من مختلف أنحاء العالم، الاطلاع على خلفياتهم التاريخية (سواء الهند أو الصين أو مناطق إفريقيا أو أوروبا) في العالم الأممي المترابط. وتنفّذ عمليات “إعادة الترتيب” و”إعادة التوجيه” على أساس مسار تاريخي سابق التوجه نحو الغرب، وضع أوروبا في قلب التطورات التاريخية العالمية. [18] وعلى غرار الروايات التاريخية الأخرى، يتبنى التاريخ العالمي العربي الفرنسي لمتحف اللوفر منظوره الخاص، حيث أنّ “عيون التاريخ” في المتحف العالمي في متحف اللوفر أبو ظبي تضع “الإنسانية” في قلب “تقاليد طويلة قائمة على المركزية والعلاقات المتبادلة” في منطقة الخليج العربي. [19]

_____________________

Further Reading

- Bauer, Thomas. Warum es kein islamisches Mittelalter gab. Das Erbe der Antike und der Orient. München: C.H. Beck, 2018.

- Exell, Karen. Modernity and Museum in the Arabian Peninsula. London: Routledge, 2016.

- Sanders, Paula. Creating Medieval Cairo. Empire, Religion and Architectural Preservation in Nineteenth-Century Egypt. Kairo, New York: The American University in Cairo Press, 2008.

Web Resources

- Louvre Abu Dhabi: https://www.louvreabudhabi.ae/ (last accessed 23 June 2020).

- Artsy: After Years of Controversy, the Louvre Abu Dhabi’s Grand Ambitions Fall Short: https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-years-controversy-louvre-abu-dhabis-grand-ambitions-fall-short (last accessed 23 June 2020).

- New York Times: Louvre Abu Dhabi, an Arabic-Galactic Wonder, Revises Art History: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/28/arts/design/louvre-abu-dhabi-united-arab-emirates-review.html (last accessed 23 June 2020).

_____________________

[1] Thomas Bauer, Warum es kein islamisches Mittelalter gab. Das Erbe der Antike und der Orient (München: C.H. Beck, 2018), 149.

[2] المرجع السابق.

[3] المرجع السابق, 23.

[4] Paula Sanders, Creating Medieval Cairo. Empire, Religion and Architectural Preservation in Nineteenth-Century Egypt (Cairo, New York: The American University in Cairo Press, 2008).

[5] راجع مشروع “عرض التنوع والدفاع عنه في المتاحف السورية” (عمار عبد الرحمن وجيني أوسترل) بتمويل من الأكاديمية العربية الألمانية الشابة للعلوم والإنسانيات ووزارة الاتحادية التعليم والبحوث في ألمانيا (2019).

[6] See Bashar Ibrahim; Jenny Oesterle, “Geschichtswissenschaften an irakischen Universitäten. Eine Bestandsaufnahme,” in: Journal des Verbands der Historikerinnen und Historiker Deutschlands 8 (2019), 64-69.

[7] Jörg Matthias Determann, “Dynastic Periodization and its Limits: Historiography in Contemporary Arab Monarchies,“ in: Der Islam 91, no. 1 (2014), S. 95–114

[8] راجع معرض “مفترق الطرق. التبادل الثقافي بين الحضارة الإسلامية وأوروبا وما بعدها “بالمتحف الإسلامي بالشارقة (2019)، بمشاركة المتحف الإسلامي في برلين. في نفس الوقت تقريبًا، عرض متحف اللوفر أبو ظبي “طرق الجزيرة العربية. كنوز المملكة العربية السعودية الأثرية “، وهو معرض صمم بقيادة ستيفان ويبر (المتحف الإسلامي في برلين).

[9] Karen Exell, Modernity and Museum in the Arabian Peninsula (London: Routledge, 2016) 5.

[10] المرجع السابق. 2.

[11] Louvre Abu Dhabi, The Complete Guide (Abu Dhabi, Paris, 2018), 5.

[12] [12] أدى تصوّر المتاحف العالمية (خاصة في العالم الغربي) إلى نقاشات نقدية حول محاولة جمع تاريخ “الثقافات” المختلفة في معرض واحد. كما أنّ عرض القطع الأثرية التي استحوذت عليها المتاحف خلال الفترة الاستعمارية لبلد ما (أخيرًا وليس آخرًا في متحف اللوفر في باريس) ومشكلة إعادتها إلى الوطن الأم تمت مناقشتها بشكل مثير للجدل. في النقاش حول المتاحف العالمية وانتقادها، راجع، على سبيل المثال، بيرغفيلت، (ed.): “مع وضدّ المتحف العالمي في عصر نابليون وبعده” ، في: إرث نابليون: بروز المتاحف الوطنية في أوروبا ، 1794-1830 ، برلين 2009 ، ص 91-100 ؛ كورتيس : “المتاحف العالمية وتحفها، وإعادتها إلى وطنها: القصص المتشابكة للأشياء”، في: إدارة المتاحف والقوامة 11 (1) ، ص 79-82 ؛ أوبوكو ، كوامي: من المتاحف العالمية إلى متاحف التراث العالمي (http://www.elginism.com/similar-cases/the-universal-museum-concept-rumbles-on/20070908/1144/;، تمّ الاطلاع عليه آخر مرّة في 28 أيار/مايو 2020).

[13] Louvre Abu Dhabi, Complete Guide, S. 7.

[14] See Wolfgang Drews, Christian Scholl, (eds.), Transkulturelle Verflechtungsprozesse in der Vormoderne, Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter, 2016; DFG Netzwerk Transkulturelle Verflechtungen, Transkulturelle Verflechtungen. Mediävistische Perspektiven (Göttingen: Universitätsverlag Göttingen, 2016); Michael Borgolte, (Ed.), Mittelalter im Labor. Die Mediävistik testet Wege zu einer transkulturellen Europawissenschaft (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 2008); Michael Borgolte, Bernd Schneidmüller (Eds.), Hybride Kulturen im mittelalterlichen Europa. Vorträge und Workshops einer Frühlingsschule (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 2010); Michael Borgolte, Matthias Tischler (Eds.), Transkulturelle Verflechtungen im mittelalterlichen Jahrtausend. Europa, Ostasien, Afrika (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 2012); Wolfram Drews, Jenny Rahel Oesterle,Transkulturelle Komparatistik. Beiträge zu einer Globalgeschichte der Vormoderne (Leipzig: Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2008); Daniel König, Katja Rakow, “Transcultural Studies: Areas and Disciplines,“ in: Transcultural Studies Journal 2 (2016).

[15] Exell, 11.

[16] Exell, 11.

[17] Louvre Abu Dhabi, Complete Guide (Jean-Francoise Charnier), 174.

[18] المرجع السابق, 21.

[19] المرجع السابق.

_____________________

Image Credits

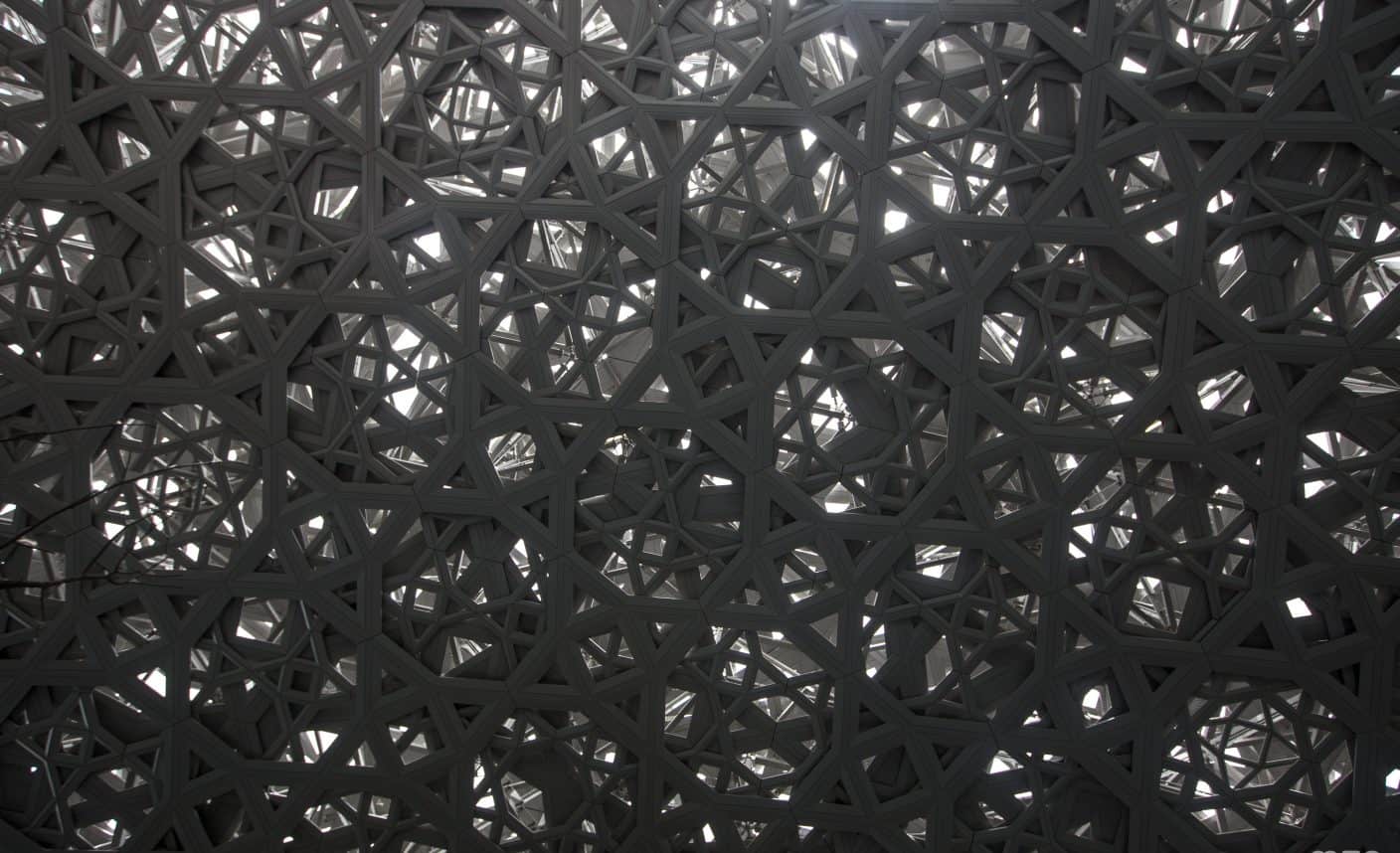

Louvre d’Abu Dhabi © 2018 mzagerp CC BY-ND 2.0 via flickr.

Recommended Citation

Oesterle-El Nabout, Jenny Rahel: وجهات نظر حول “العصور الوسطى” في متحف اللوفر أبوظبي. In: Public History Weekly 8 (2020) 6, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2020-16559.

Editorial Responsibility

Thomas Bauer recently argued that the Islamic Middle Ages never existed: the concept of an “Islamic Middle Ages” is “imprecise,”[1] leads to “incorrect conclusions”[2] and is “deeply Eurocentric.”[3] This important criticism of the Western classification of periods and their unreflected transposition to other world regions could be complemented by another perspective: Arab epochal classifications, designations and conceptions, derived from both the historical sciences and the public culture of memory and history – for example, in museums. Considering Arab positions in the debate on the classifications of epochs and conceptions of history leads to further differentiations, which above all concern the relationship between “Western” and “Arab” uses and shaping of the concept of the so-called Middle Ages.

What do you mean by Middle Ages?

The negative, appropriating and alienating aspect of epochal classifications must be considered alongside Arab self-representations, self-conceptions and assurances of identity in ideas about their own historical “Middle Ages.” Western periodization criteria are not always adopted one-sidedly or taken at face value “from the West” and applied to the Arab past. Arab scholars and culture professionals, whether at universities or in museums, contribute to the specific, time- and context-related definition and contouring of such criteria, often in exchange with Western ideas.

The “Middle Ages” are diversely enriched in the process: In the 19th century, for example, international and Egyptian conservators defined the “Middle Ages” in the Sunni-Mamluk sense for the capital Cairo; they molded this definition of the “Middle Ages” in the national interest against Ottoman rule, while the memory of the Shia-Fatimid rule, to which the foundation of Cairo was indebted, was long barely visible in the public cityscape.[4] Such a narrowing of the “Middle Ages” to a specific dynasty, with long-term visible consequences for the restoration of Cairo, is not a purely Western transposition. It was also in Egypt’s interest and pursued by the Egyptians. Currently, Syrian museum curators,[5] Iraqi historians[6] or historians of the Arab Gulf monarchies[7] are approaching the epochal classifications of their own history differently. Instead of a single epoch called “the Middle Ages” and transposed from “the West,” several “Ages of the Middle” also coexist from the Arab point of view and in the thinking of scholars and culture professionals. This is consistent with the plural Arabic term for the Middle Ages (al-ʿuṣūr al-wusṭa). There is therefore a certain resistance to being appropriated, in a one-sided temporal and cultural manner, into a Western development of history leading to modernity. This allows for the open-minded use of academic know-how from the “western” world, while considering the complex interrelationships between origin, interests and use, and thus also cultural productivity in which the Arab side knows how to assert its independence and self-interest.

The following remarks do not focus on the historical sciences at Arab universities in the narrower sense, but on the broader field of the culture of memory and history culture (public history). Prominent media addressing cultural productivity in the not exclusively academic field of public history are, for example, newly founded museums in the Arab Gulf states. Be it the National Museum of Qatar, the Islamic Museum in Sharjah[8] or the Louvre Abu Dhabi: Although the museum as a medium originated in the Western world, it is used here as a “master stroke of cultural diplomacy and an example of regional agency in a globalized world.”[9] In 21st-century Arab Gulf states, where the number of migrant workers from around the world exceeds that of the natives many times over, museums are staged as “global cultural centers, not just within the Arab world but also in relation to the West”[10] and other Eastern and Southern parts of the world. As “global centers,” they present their visitors with a historical view and historical objects that are not limited to the history of their own Arab region, but are global in scope. Exhibits are viewed by locals and visitors from all over the world, whether they are tourists or members of the local multicultural global middle class.

Always a Hub Between East and West

“See Humanity through the Eyes of History”: This is the slogan that the Louvre Abu Dhabi, which opened in 2017, uses to advertise its exhibitions. Although the museum emerged from a Franco-Arab joint venture, its underlying concept is much more than a mere offshoot of the famous Parisian museum: The Louvre Abu Dhabi has its own identity, as “a universal museum, telling the stories that have united humans beyond the restriction of time and place.” This is how His Excellency Muhammad Khalifa al-Mubarak, the Chairman of the “Department for Culture and Tourism” in Abu Dhabi, outlined the museum’s programmatic historical dimension. The exhibition demonstrates the Emirate’s self-conception as “a welcoming and meeting place for different cultures and religions” in the world. The Louvre’s exhibitions are intended to convey the ideas that the region has always been a hub between East and West, even in the past. At present, it is important to create global connections in history and culture; the Louvre Abu Dhabi is “what is now such an interconnected world.”[11] The museum positions itself as a universal museum[12] that is destined for this purpose, not least thanks to its geographical location.

Its location in Abu Dhabi is special, according to Saif Saeed Ghosbash, Director General of the Department of Culture and Tourism. The region is characterized by a unique disposition for contact and exchange, both past and present; its center, according to the emirate’s programmatic self-conception, is today’s Abu Dhabi. The Louvre Abu Dhabi uses this initial disposition as a privilege for a seminal 21st-century museum with a universal horizon:

“Geographically and intellectually, the museum sits at a crossroad between east and west. For centuries, the region was an important point on the Silk Road, which connected Arabia with Asia, Europe and the Horn of Africa. However, the Silk Road was not simply a route for the exchange of goods, it also made possible the sharing of new skills and new ideas. In today’s global marketplace, Abu Dhabi is once again at the heart of a powerful network of economic and cultural relationships. Louvre Abu Dhabi draws together these historic and contemporary links across global cultures. The result is a universal museum for the twenty-first century.”[13]

Until recently, German history has also known problematic instances of imagination from the Middle Ages. However, these Arab representations of the Gulf region’s past are not historical imaginations, but rather an idea that is consistent with the Arab experience and knowledge of the world at the time and based on their own relations.

The “Middle Ages” are presented in the Louvre Abu Dhabi as a phase of global centrality, productive multiculturalism, exchange of knowledge, coexistence, intensive mobility and inter-religious contacts. This approach is in line with the research of transcultural history being pursued by medieval studies in Germany and other Western countries for about two decades.[14] However, assuming that Western research trends in medieval studies have merely been transposed to designing the Louvre Abu Dhabi without considering the Emirati initiators’ own interests would be biased: A historical narrative of productivity through cultural contact, of global networks, in which the Arab Gulf region has always held a key geographical position, also corresponds to current fundamental political policy in the United Arab Emirates.

It can also be understood as offering cultural identity in a society balancing tradition and modernity, among others, in the coexistence of local minorities and multicultural migrant workers. Since the country faces the challenges of its own global positioning and internal stabilization of identity in a rapidly changing multireligious, multicultural and multiethnic society — where the ruling Arab-Islamic elite of the Emirates is a minority, but where tradition and religion still play a decisive role —, the museum genre originating from Western culture is specifically used for today’s Abu Dhabi

as a “tool in the construction of the nation through the legitimization of the ruling family and the narration of a consistent historical narrative and, finally, as means of branding nations and gaining symbolic global power through accessing cultural capital.”[15]

A World in Motion

The chronology of this “consistent historical narrative”[16] becomes the backbone of the exhibition; visitors wander through the world of Antiquity and then, after the fall of ancient empires, arrive at galleries presenting epochs from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance; these galleries are devoted to the world religions without emphasizing any in particular: Buddhism, Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, Confucianism and Taoism. A second focal point is the trade routes such as the Silk and Pottery Roads, East-West contacts over land and sea all the way to the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, and finally, science and technology in exchange and global world conceptions using the examples of geometry and cartography, polyglot contacts at courts and lifestyle. Connectivity, mobility, transculturality and transfer are the focus of a world in motion.

The recurring compilation of three individual, more or less simultaneous artefacts of different cultural-religious origin that reference each other thematically highlights a structural feature of the exhibition. There is no one-sided Western orientation. Exhibits from China or Mexico, India or Europe are equally important in the period between Antiquity and the dawn of Modernity; they are also assigned to one another. However, the location of the United Arab Emirates in the global “middle” between the South, North, West and East remains critical for this perspective. Conflict and war, dissonance and enmities remain largely ignored. If warlike conflicts are mentioned, as in the case of the Crusades, they are productively reinterpreted as the possibility of expanding and intensifying contacts, for example, to establish trade relations:

“Above and beyond the armed conflict, the period of the Crusades and the founding of shortlived Frankish states in the Levant took tangible form in increased trade between the Latin West and the Islamic East.”[17]

Visitors, be they Emirati, tourists or middle-class migrant workers from all over the world, can recognize their own historical backgrounds (whether India, China, regions of Africa or Europe) in the interdependent global world. “Relocalization” and “reorientation” are being carried out in relation to a previously Western-oriented course of history, which had placed Europe at the center of world historical developments.[18] Like other historical narratives, the Arab-French universal history of the Louvre also adopts its specific perspective: The “eyes of history” in the Universal Museum of the Louvre Abu Dhabi place “humanity” in the Arab Gulf region’s “long tradition of centrality and interrelations.”[19]

_____________________

Further Reading

- Bauer, Thomas. Warum es kein islamisches Mittelalter gab. Das Erbe der Antike und der Orient. München: C.H. Beck, 2018.

- Exell, Karen. Modernity and Museum in the Arabian Peninsula. London: Routledge, 2016.

- Sanders, Paula. Creating Medieval Cairo. Empire, Religion and Architectural Preservation in Nineteenth-Century Egypt. Kairo, New York: The American University in Cairo Press, 2008.

Web Resources

- Louvre Abu Dhabi: https://www.louvreabudhabi.ae/ (last accessed 23 June 2020).

- Artsy: After Years of Controversy, the Louvre Abu Dhabi’s Grand Ambitions Fall Short: https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-years-controversy-louvre-abu-dhabis-grand-ambitions-fall-short (last accessed 23 June 2020).

- New York Times: Louvre Abu Dhabi, an Arabic-Galactic Wonder, Revises Art History: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/28/arts/design/louvre-abu-dhabi-united-arab-emirates-review.html (last accessed 23 June 2020).

_____________________

[1] Thomas Bauer, Warum es kein islamisches Mittelalter gab. Das Erbe der Antike und der Orient (München: C.H. Beck, 2018), 149.

[2] Ibd.

[3] Ibd., 23.

[4] Paula Sanders, Creating Medieval Cairo. Empire, Religion and Architectural Preservation in Nineteenth-Century Egypt (Cairo, New York: The American University in Cairo Press, 2008).

[5] See the project “Exhibiting and Defending Diversity in Syrian Museums” (Ammar Abdulrahman and Jenny Oesterle), funded by the Arab German Young Academy of Sciences and Humanities and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (2019).

[6] See Bashar Ibrahim; Jenny Oesterle, “Geschichtswissenschaften an irakischen Universitäten. Eine Bestandsaufnahme,” in: Journal des Verbands der Historikerinnen und Historiker Deutschlands 8 (2019), 64-69.

[7] Jörg Matthias Determann, “Dynastic Periodization and its Limits: Historiography in Contemporary Arab Monarchies,“ in: Der Islam 91, no. 1 (2014), S. 95–114

[8] See the exhibition Ausstellung “Crossroads. Cultural Exchange between the Islamic Civilization, Europe and Beyond“ at the Islamic Museum of Sharjah (2019), with the participation of the Islamic Museum Berlin, among others. At about the same time, the Louvre Abu Dhabi showed “Roads of Arabia. Archaeological Treasures of Saudi Arabia,” an exhibition designed under the leadership of Stefan Weber (Islamic Museum Berlin).

[9] Karen Exell, Modernity and Museum in the Arabian Peninsula (London: Routledge, 2016) 5.

[10] Ibd., 2.

[11] Louvre Abu Dhabi, The Complete Guide (Abu Dhabi, Paris, 2018), 5.

[12]The conceptualization of universal museums (especially in the Western world) has led to critical discussions of the attempt to bring together the history of different “cultures” in one exhibition. The presentation of artefacts that museums came to own during a country’s colonial period (last but not least also at the Louvre Paris) and the problem of repatriation are controversially discussed. On the debate about and criticism of universal museums, see, for example, Andrew McClellan, “For and against the Universal Museum in and after the Age of Napoleon,“ in: Napoleon’s legacy: the rise of national museums in Europe, 1794-1830, ed. Ellinoor Bergvelt (Berlin 2009), 91-100; N.G. Curtis, “Universal Museums, museum objects and repratriation: the tangled stories of things,“ in: Museum management and Curatorship 11 (1), 79-82; Kwame Opoku, From Universal Museums to Universal Heritage Museums, http://www.elginism.com/similar-cases/the-universal-museum-concept-rumbles-on/20070908/1144/ (last accessed 23 June 2020)

[13] Louvre Abu Dhabi, Complete Guide, S. 7.

[14] See Wolfgang Drews, , Christian Scholl, (eds.), Transkulturelle Verflechtungsprozesse in der Vormoderne, Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter, 2016; DFG Netzwerk Transkulturelle Verflechtungen, Transkulturelle Verflechtungen. Mediävistische Perspektiven (Göttingen: Universitätsverlag Göttingen, 2016); Michael Borgolte, (Ed.), Mittelalter im Labor. Die Mediävistik testet Wege zu einer transkulturellen Europawissenschaft (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 2008); Michael Borgolte, Bernd Schneidmüller (Eds.), Hybride Kulturen im mittelalterlichen Europa. Vorträge und Workshops einer Frühlingsschule (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 2010); Michael Borgolte, Matthias Tischler (Eds.), Transkulturelle Verflechtungen im mittelalterlichen Jahrtausend. Europa, Ostasien, Afrika (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 2012); Wolfram Drews, Jenny Rahel Oesterle,Transkulturelle Komparatistik. Beiträge zu einer Globalgeschichte der Vormoderne (Leipzig: Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2008); Daniel König, Katja Rakow, “Transcultural Studies: Areas and Disciplines,“ in: Transcultural Studies Journal 2 (2016).

[15] Exell, 11.

[16] Exell, 11.

[17] Louvre Abu Dhabi, Complete Guide (Jean-Francoise Charnier), 174.

[18] Ibd., 21.

[19] Ibd.

_____________________

Image Credits

Louvre d’Abu Dhabi © 2018 mzagerp CC BY-ND 2.0 via flickr.

Recommended Citation

Oesterle-El Nabout, Jenny Rahel: Perspectives on the “Middle Ages” in the Louvre Abu Dhabi. In: Public History Weekly 8 (2020) 6, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2020-16559.

Editorial Responsibility

Ein islamisches Mittelalter hat es nicht gegeben, so die These des Islamwissenschaftlers Thomas Bauer in seinem jüngsten Essayband. Der Ausdruck “islamisches Mittelalter” sei “ungenau”[1], führe zu “Fehlschlüssen”[2] und sei “zutiefst eurozentristisch”[3]. Die wichtige Kritik Thomas Bauers an westlichen Periodisierungsschemata und ihren unreflektierten Übertragungen auf andere Weltregionen ist um eine weitere Sichtweise zu ergänzen: Einzubeziehen sind der ‘eigene’ Gebrauch von Epochengliederungen, –bezeichnungen und -vorstellungen in der arabischen Welt und zwar sowohl in der arabischen Geschichtswissenschaft als auch der öffentlichen Erinnerungs- und Geschichtskultur – zum Beispiel in Museen. Die Berücksichtigung arabischer Positionen in der Debatte um Epochengliederungen und Geschichtsvorstellungen führt zu weiteren notwendigen Differenzierungen, die vor allem das Verhältnis ‚westlicher‘ und ‚arabischer‘ Beteiligungen an Verwendung und Ausgestaltung des Mittelalterbegriffs betrifft.

Was heisst hier Mittelalter?

Der negativen, vereinnahmenden, fremd-zuschreibenden Seite von Epocheneinteilungen stehen arabische Selbstentwürfe, Selbstbilder und Identitätsvergewisserungen in Vorstellungen eines eigenen geschichtlichen Mittelalters zur Seite. Nicht immer wird einseitig die westliche Periodisierungsvorgabe übernommen oder einlinig ‘aus dem Westen’ auf die eigene Vergangenheit übertragen. Arabische Wissenschaftler und Kulturschaffende, sei es an Universitäten oder in Museen, tragen zu ihrer je spezifischen, zeit- und kontextbezogenen Bestimmung und Konturierung bei, häufig im Austausch mit westlichen Impulsen.

Dabei wird ‘Mittelalter’ mit verschiedenen Inhalten angereichert: Internationale und ägyptische Restauratoren definierten beispielsweise im 19. Jahrhundert ‘Mittelalter’ im sunnitisch-mamlukischen Sinn für die Hauptstadt Kairo; sie profilierten diese Prägung von ‘Mittelalter’ im nationalstaatlichen Interesse gegen die Osmanenherrschaft, während die Erinnerung an die schiitisch-fatimidische Herrschaft, der sich die Gründung Kairos verdankt, im öffentlichen Stadtbild lange Zeit kaum sichtbar wurde.[4] Eine derartige Verengung von ‘Mittelalter’ auf eine bestimmte Dynastie mit langfristig sichtbaren Folgen für Restaurationsgestaltungen Kairos ist keine rein westliche Übertragung, sondern lag durchaus auch im ägyptischen Interesse und wurde auch von ägyptischer Seite betrieben. Anders gehen aktuell syrische Museumskuratoren,[5] irakische Historiker[6] oder Historiker der arabischen Golfmonarchien[7] mit Epochengliederungen der eigenen Geschichte um. Statt einer einzigen, westlich übertragenen Epoche Mittelalter koexistieren auch aus arabischer Sicht und in den Vorstellungen von Wissenschaftlern und Kulturschaffenden mehrere ‘Zeitalter der Mitte’. Das entspricht dem pluralen arabischen Mittelalterbegriff (al-ʿuṣūr al-wusṭa). Es existiert daher eine gewisse Widerständigkeit gegenüber einer einseitigen zeitlichen und kulturellen Vereinnahmung in eine westliche, auf die Moderne hinführende Entwicklung der Geschichte. Möglich wird dadurch eine aufgeschlossene Nutzung wissenschaftlichen know hows der ‘westlichen’ Welt mit Rücksicht auf vielschichtige Entstehungs-, Interessens- und Verwendungszusammenhänge und damit auch eine kulturelle Produktivität, in der die arabische Seite Eigenständigkeit und Eigeninteresse zu behaupten weiß.

Folgende Ausführungen konzentrieren sich nicht auf die arabische Geschichtswissenschaft im engeren Sinne, sondern auf den weiteren Bereich der Erinnerungs- und Geschichtskultur (public history). Prominente Medien kultureller Produktivität im nicht ausschließlich akademischen Feld der public history sind zum Beispiel neu gegründete Museen in den arabischen Golfstaaten. Sei es das National Museum of Qatar, das Islamic Museum in Sharjah[8] oder der Louvre Abu Dhabi: Das Museum ist zwar ein in der westlichen Welt entstandenes Medium, aber es wird hier eingesetzt als ein “master stroke of cultural diplomacy and a example of regional agency in a globalized world”.[9] In den arabischen Golfstaaten des 21. Jahrhunderts, in denen die Anzahl der global zugewanderten migrant worker die der Einheimischen um ein Vielfaches übertrifft, inszenieren sich Museen zu “global cultural centers, not just within the Arab world but also in relation to the West”[10] und anderen östlichen wie südlichen Weltteilen. Als “globale Zentren” präsentieren sie ihren Besuchern eine geschichtliche Sicht und historische Gegenstände, die sich nicht auf die Geschichte der eigenen, arabischen Region beschränken, sondern global angelegt sind. Sie werden von Einheimischen und Besuchern aus der ganzen Welt betrachtet, seien es Touristen oder Angehörige der dortigen multikulturellen globalen Mittelschicht.

Stets ein Drehkreuz zwischen Ost und West

“See Humanity through the Eyes of History”: mit diesem Slogan wirbt der im Jahr 2017 eröffnete Louvre Abu Dhabi für den Besuch seiner Ausstellungen. Das Museum entstand aus einem französisch-arabischen joint venture; seinem Konzept nach ist es weit mehr als ein bloßer Ableger des berühmten Pariser Museums: Der Louvre Abu Dhabi sei ein Museum mit eigener Identität, “a universal museum, telling the stories that have united humans beyond the restriction of time and place”. So umriss seine Exzellenz Muhammad Khalifa al-Mubarak, der Vorsitzende des “Department for Culture and Tourism” in Abu Dhabi dessen programmatische geschichtliche Dimensionierung. Die Ausstellung führt das Selbstverständnis des Emirats vor Augen, “a welcoming and meeting place for different cultures and religions” der Welt zu sein. Auch in der Vergangenheit, so soll die Ausstellung des Louvre vermitteln, sei die Region über Jahrhunderte stets ein Drehkreuz zwischen Ost und West gewesen. Gegenwärtig gelte es, globale Verbindungen in Geschichte und Kultur stiften; der Louvre Abu Dhabi sei “what is now such an interconnected world”.[11] Dabei positioniert sich das Museum als Universalmuseum,[12] das nicht zuletzt auch dank seiner geographischen Lage dafür prädestiniert sei.

Der Sitz des Louvre in Abu Dhabi ist nach den Worten des Direktor des Departments, Saif Saeed Ghosbash ein besonderer Ort. In Geschichte und Gegenwart zeichnet sich die Region durch eine einzigartige Kontakt- und Austauschdisposition aus; sein Zentrum, so das programmatische Selbstbild des Emirats, ist das heutige Abu Dhabi. Der Louvre Abu Dhabi nutzt diese Ausgangsdisposition als Privilegierung zu einem zukunftshaltigen Museum des 21. Jahrhunderts mit universalem Horizont:

“Geographically and intelectually, the museum sits at a crossroad between east and west. For centuries, the region was an important point on the Silk Road, which connected Arabia with Asia, Europe and the Horn of Africa. However, the Silk Road was not simply a route for the exchange of goods, it also made possible the sharing of new skills and new ideas. In today’s global marketplace, Abu Dhabi is once again at the heart of a powerful network of economic and cultural relationships. Louvre Abu Dhabi draws together these historic and contemporary links across global cultures. The result is a universal museum for the twenty-first century”.[13]

Die deutsche Geschichte kennt bis in die jüngste Zeit folgenreiche Imaginationen des Mittelalters. Doch um eine historische Imagination handelt es sich bei diesen arabischen Vergegenwärtigungen der Vergangenheit der Golfregion nicht, eher um eine Vorstellung, die der damaligen arabischen Welterfahrung und –kenntnis auf der Basis eigener Beziehungen entspricht.

‘Mittelalter’ wird im Louvre Abu Dhabi als Phase globaler Zentralität, produktiver Multikulturalität, des Austauschs von Wissen, Koexistenz, intensiver Mobilität und interreligiösen Kontakte präsentiert. Dieser Ansatz entspricht durchaus einer auch von der Mediävistik in Deutschland und anderen westlichen Ländern seit rund zwei Jahrzehnten verfolgten Erforschung transkultureller Geschichte.[14] Die Annahme einer bloßen Übertragung westlicher Forschungstrends in der Mediävistik auf die Museumsgestaltung in Abu Dhabi ohne eigene Interessen der emiratischen Initiatoren wäre aber verkürzt: Eine Geschichtserzählung von Produktivität durch Kulturkontakt, von globalen Netzwerken, in denen der arabischen Golfregion seit jeher eine geographische Schlüsselstellung zukomme, entspricht auch aktuellen politischen Prämissen in den Vereinigten Arabischen Emiraten.

Sie kann auch als kulturelles Identitätsangebot in einer Gesellschaft zwischen Tradition und Moderne im Zusammenleben lokaler Minderheiten und multikultureller migrant worker verstanden werden. Angesichts der Herausforderungen einer eigenen globalen Positionierung und inneren Identitätsstabilisierung in einer sich rapide wandelnden multureligiösen, multikulturellen und multiethnischen Gesellschaft, in der die herrschende arabisch-islamische Elite der Emirate eine Minderheit darstellt, Tradition und Religion aber nach wie vor eine maßgebliche Rolle spielen, wird das aus der westlichen Kultur stammende Museumsgenre gezielt eingesetzt für das heutige Abu Dhabi

als ein “tool in the construction of the nation through the legitimization oft he ruling family and the narration of a consistant historical narrative and, finally, as means of branding nations and gaining symbolic global power through accessing cultural capital”.[15]

Eine Welt in Bewegung

Die Chronologie dieses “consistant historical narrative”[16] wird dabei zum Rückgrat der Ausstellung; Besucher*innen durchwandern die Welt der Antike und gelangen dann, nach dem Untergang antiker Imperien, in Galerien, die das mittlere Zeitalter bis zur Renaissance vorstellen; sie widmen sich den Weltreligionen, ohne eine einzelne davon besonders hervorzuheben: Buddhismus, Christentum, Judentum, Islam, Hinduismus, Konfuzianismus und Taoismus. Einen zweiten Schwerpunkt stellen Handelsrouten wie die Seiden- und Keramikstrassen, Ost-West Kontakte über Land und Meer bis zum Mittelmeerraum und Atlantik dar, schließlich Wissenschaften und Technik im Austausch und globale Weltentwürfen am Beispiel von Geometrie und Kartographie, polyglotte Kontakte an Höfe und Lebensart. Konnektivität, Mobilität, Transkulturalität und Transfer stehen im Fokus einer Welt in Bewegung.

Die wiederkehrende Zusammenstellung von je drei thematisch und motivlich aufeinander verwiesener, einzelner, mehr oder weniger zeitgleicher Artefakte verschiedener kulturell-religiöser Herkunft markiert ein Strukturmerkmal der Ausstellung. Es gibt keine einseitige Orientierung auf den Westen. In die Zeit zwischen Antike und dem Aufbruch in die Moderne sind Exponate aus China oder Mexiko, Indien oder Europa gleichgewichtig einbezogen und einander zugeordnet. Blickbestimmend aber bleibt die Situierung der Vereinigten Arabischen Emirate in der globalen ‘Mitte’ der Vereinigten Arabischen Emirate zwischen Süd, Nord, West und Ost. Weitestgehend ausgeblendet bleiben Konflikt und Krieg, Dissonanzen, Störungen, Feindschaften. Finden kriegerische Auseinandersetzungen Erwähnung, wie im Fall der Kreuzzüge, werden sie produktiv umgedeutet zur Möglichkeit der Kontakterweiterung und –intensivierung etwa von Handelsbeziehungen:

“Above and beyond the armed conflict, the period of the Crusades and the founding of shortlived Frankish states in the Levant took tangible form in increased trade between the Latin West and the Islamic East”.[17]

Besucher*innen, seien es Emirati, Tourist*innen oder mittelständische migrant workers aus aller Welt, können je eigene Herkunftsgeschichten (sei es Indiens, Afrikas, Chinas oder Europas) in ihrer globalen Verflechtung erkennen. Vollzogen wird eine Re-Lokalisierung und Reorientierung[18] gegenüber einem bislang westlich ausgerichteten Gang der Geschichte, der Europa ins Zentrum der weltgeschichtlichen Entwicklungen gestellt hatte. Wie andere Geschichtserzählungen ist auch die arabisch-französisch gestaltete Universalgeschichte des Louvre perspektivisch ausgerichtet: Durch die “Augen der Geschichte” erscheint die “Menschheit” im Universalmuseum des Louvre Abu Dhabi in einer “long tradition of centrality and interrelations”[19] der arabischen Golfregion.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Bauer, Thomas. Warum es kein islamisches Mittelalter gab. Das Erbe der Antike und der Orient. München: C.H. Beck, 2018.

- Exell, Karen. Modernity and Museum in the Arabian Peninsula. London: Routledge, 2016.

- Sanders, Paula. Creating Medieval Cairo. Empire, Religion and Architectural Preservation in Nineteenth-Century Egypt. Kairo, New York: The American University in Cairo Press, 2008.

Webressourcen

- Louvre Abu Dhabi: https://www.louvreabudhabi.ae/ (letzter Zugriff 23. Juni 2020).

- Artsy: After Years of Controversy, the Louvre Abu Dhabi’s Grand Ambitions Fall Short: https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-years-controversy-louvre-abu-dhabis-grand-ambitions-fall-short (letzter Zugriff 23. Juni 2020).

- New York Times: Louvre Abu Dhabi, an Arabic-Galactic Wonder, Revises Art History: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/28/arts/design/louvre-abu-dhabi-united-arab-emirates-review.html (letzter Zugriff 23. Juni 2020).

_____________________

[1] Thomas Bauer, Warum es kein islamisches Mittelalter gab. Das Erbe der Antike und der Orient (München: C.H. Beck, 2018), 149.

[2] Ibd.

[3] Ibd., 23.

[4] Paula Sanders, Creating Medieval Cairo. Empire, Religion and Architectural Preservation in Nineteenth-Century Egypt (Cairo, New York: The American University in Cairo Press, 2008).

[5] Vgl. dazu das Projekt “Exhibiting and Defending Diversity in Syrian Museums“ (Ammar Abdulrahman und Jenny Oesterle), gefördert von der Arab German Young Academy of Sciences and Humanies und dem Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (2019).

[6] Vgl. Bashar Ibrahim; Jenny Oesterle: “Geschichtswissenschaften an irakischen Universitäten. Eine Bestandsaufnahme,”in: Journal des Verbands der Historikerinnen und Historiker Deutschlands 8 (2019), S. 64-69 sowie das Projekt “Historians and Historical Research at Iraqi Universities“ gefördert von der Arab German Young Academy of Sciences and Humanies und dem Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (seit 2018).

[7] Jörg Matthias Determann, “Dynastic Periodization and its Limits: Historiography in Contemporary Arab Monarchies,“ in: Der Islam 91, no. 1 (2014), S. 95–114

[8] Vgl die Ausstellung Ausstellung “Crossroads. Cultural Exchange between the Islamic Civilization, Europe and Beyond“ im Islamic Museum of Sharjah (2019) unter Mitwirkung unter anderem des Islamischen Museums Berlin. Der Louvre Abu Dhabi zeigte etwa zeitgleich die von Stefan Weber (islamisches Museum Berlin) federführend konzipierte Ausstellung “Roads of Arabia. Archaeological Treasures of Saudi Arabia“.

[9] Karen Exell, Modernity and Museum in the Arabian Peninsula (London: Routledge, 2016) 5.

[10] Ibd., 2.

[11] Louvre Abu Dhabi, The Complete Guide (Abu Dhabi, Paris, 2018), 5.

[12] Die Konzeptionalisierung von Universalmuseen (insbesondere in der westlichen Welt) führte zu kritischen Auseinandersetzungen mit dem Versuch, die Geschichte verschiedener ‚Kulturen‘ in einer oder mehreren Ausstellungen zusammenzuführen. Kontrovers diskutiert wird die Frage der Präsentation von Artefakten, die in der Kolonialzeit eines Landes in den Besitz von Museen gekommen waren (auch im Louvre Paris) und das Problem von Repatriierungen. Zur Debatte um und Kritik an Universalmuseen vgl. etwa Andrew McClellan, “For and against the Universal Museum in and after the Age of Napoleon,“ in: Napoleon’s legacy: the rise of national museums in Europe, 1794-1830, ed. Ellinoor Bergvelt (Berlin 2009), 91-100; N.G. Curtis, “Universal Museums, museum objects and repratriation: the tangled stories of things,“ in: Museum management and Curatorship 11 (1), 79-82; Kwame Opoku, From Universal Museums to Universal Heritage Museums, http://www.elginism.com/similar-cases/the-universal-museum-concept-rumbles-on/20070908/1144/ (letzer Zugriff 23. Juni 2020)

[13] Louvre Abu Dhabi, Complete Guide, S. 7.

[14] Vgl. Wolfgang Drews, Christian Scholl, (eds.), Transkulturelle Verflechtungsprozesse in der Vormoderne, Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter, 2016; DFG Netzwerk Transkulturelle Verflechtungen, Transkulturelle Verflechtungen. Mediävistische Perspektiven (Göttingen: Universitätsverlag Göttingen, 2016); Michael Borgolte, (Ed.), Mittelalter im Labor. Die Mediävistik testet Wege zu einer transkulturellen Europawissenschaft (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 2008); Michael Borgolte, Bernd Schneidmüller (Eds.), Hybride Kulturen im mittelalterlichen Europa. Vorträge und Workshops einer Frühlingsschule (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 2010); Michael Borgolte, Matthias Tischler (Eds.), Transkulturelle Verflechtungen im mittelalterlichen Jahrtausend. Europa, Ostasien, Afrika (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 2012); Wolfram Drews, Jenny Rahel Oesterle,Transkulturelle Komparatistik. Beiträge zu einer Globalgeschichte der Vormoderne (Leipzig: Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2008); Daniel König, Katja Rakow, “Transcultural Studies: Areas and Disciplines,“ in: Transcultural Studies Journal 2 (2016).

[15] Exell, 11.

[16] Exell, 11.

[17] Louvre Abu Dhabi, Complete Guide (Jean-Francoise Charnier), 174.

[18] Ibd., 21.

[19] Ibd.

_____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

Louvre d’Abu Dhabi © 2018 mzagerp CC BY-ND 2.0 via flickr.

Übersetzung

Translated from English by Dr Mark Kyburz (http://www.englishprojects.ch/)

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Oesterle-El Nabout, Jenny Rahel: Perspektiven auf das “Mittelalter” im Louvre Abu Dhabi. In: Public History Weekly 8 (2020) 6, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2020-16559.

Redaktionelle Verantwortung

Copyright (c) 2020 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 8 (2020) 6

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2020-16559

Tags: Arab world, Islam, Language: Arabic, Middle Ages (Mittelalter), Museum, Speakerscorner