Abstract: Etymology makes for fascinating study, even if the history of a word does not necessarily tell us anything important about its contemporary meaning. Despite its limitations, perhaps etymology can point to subterranean connections between words, spark possibilities for reflection and, thus, create or make explicit neglected semantic possibilities?

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-14054.

Languages: English, Deutsch

Etymology makes for fascinating study, even if the history of a word does not necessarily tell us anything important about its contemporary meaning. Despite its limitations, perhaps etymology can point to subterranean connections between words, spark possibilities for reflection and, thus, create or make explicit neglected semantic possibilities?

Stet – ‘let it stand’

Consider the words “statue”, “constitution” and “restitution.” All share a common Latin root in “statuĕre, to set up place.”[1] A statute is raised-up and made to “stand.” Something that is constituted is “set up” and established. Finally, “restitution” stands something back up again – restoring a status that it is claimed it had before damage or injustice was done. “Stet” one used to write – when reading proofs of text – where one changed one’s mind about a deletion and wanted, instead, to “let it stand.” These considerations came to mind – some years back – reading a passage in Pierre Bourdieu’s Language and Symbolic Power and they resonate with contemporary debate and action about erecting and/or taking-down statues and monuments, mainstreamed in contemporary culture by controversies in Bristol, Charlottesville and elsewhere.[2]

Destituting and Instituting: Pierre Bourdieu

Bourdieu writes of “more or less socially based acts of institution and destitution” through which status-bearing predicates are attached to (or detached from) individuals. He argues that such acts of destitution/institution help “to construct the reality” of the “world” by “helping to impose a more or less authorized way of seeing the social world.”[3]

Bourdieu’s usage is unconventional in English – the terms “institution” and “institute” are typically used as nouns not as verbs and are rarely used to refer to acts. An “institution” – a school, a university, a church – is often simply spoken of as a given: as a framework within which action takes place, rather than as something whose ongoing existence depends on continuous social action. “Destitution”, similarly, is often thought of as a state of affairs – when one speaks of “the destitute” to refer to the poor, it is typically to speak of those “in” a state of absolute poverty and, as often as not, speaking in this way does not entail considering possible agents of destitution who have “acted” to bring out this state of affairs.

Schematizing Bourdieu

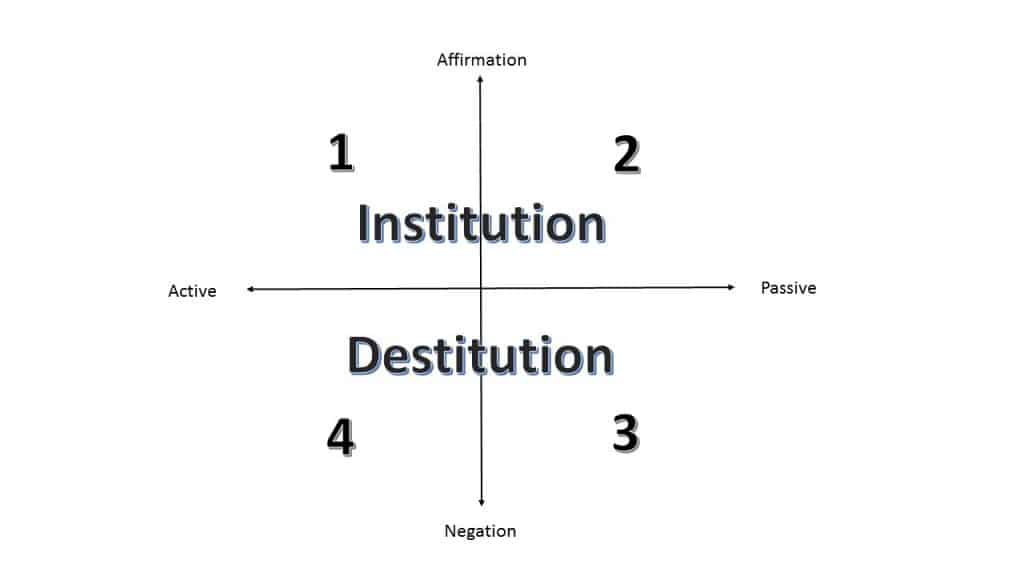

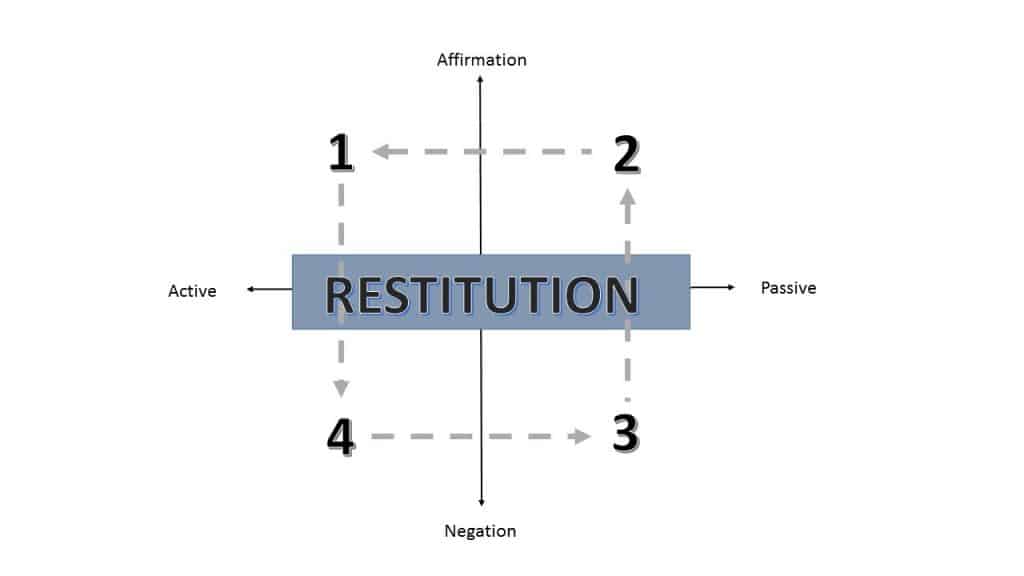

Destitution and institution clearly have applications in discussions of historical culture. Why are certain memories, events and historical figures “instituted” – raised-up in statues, in road signs, in libraries, in school curricula, and so on? Why are other memories, events and historical figures “destituted” – given a negative meaning or actively or passively erased from the “record” or – in the case of statues whose status is revised – razed to the ground? One can imagine typologies and continua that could be developed for analysing processes of “institution” and “destitution” of various kinds, such as that represented in the Figure 1, below.

Fig. 1: Schema for Institution/Destitution

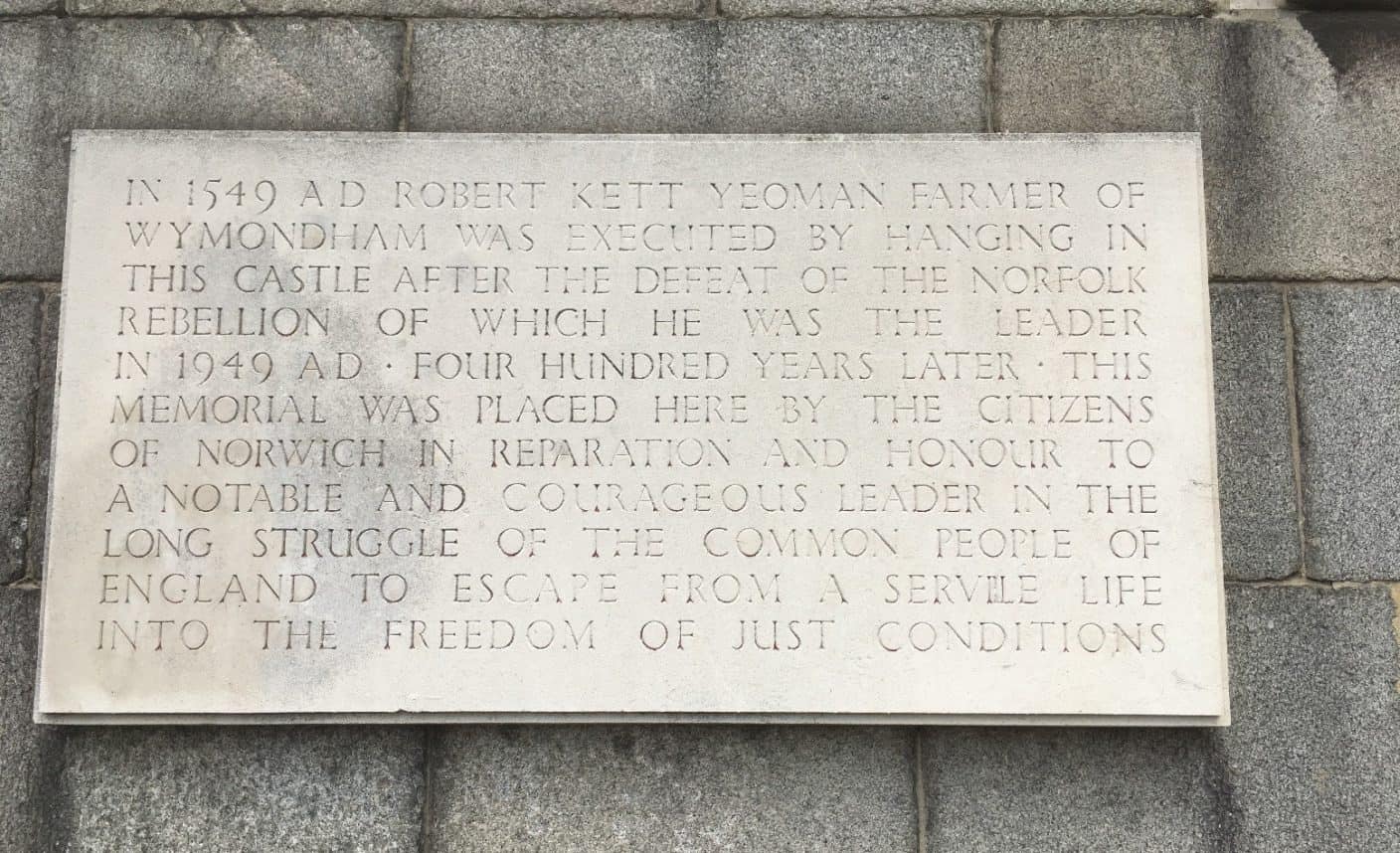

We can distinguish between remains or representations of the past that are actively affirmed or actively negated – such as statues that are erected (Quadrant 1 on the figure) or taken down (Quadrant 4 on the figure). We can also distinguish between remains or representations of the past that are simply present and passively maintained – say an old building, still in use, and still named after its founder who no one notices or remembers (Quadrant 2) – or passively neglected – say a grave that is forgotten and allowed to fall into decay (Quadrant 3). Sometimes – as in our image of the plaque commemorating Robert Kett on the wall of Norwich Castle where he was executed – we can talk of institution and destitution taking place simultaneously – the plaque “rescues” Kett from oblivion and celebrates him as a hero in the fight for social justice and represents the castle as a tool of repression imposing a “servile life” on the people for centuries. We can use these distinctions to model processes of challenge and contestation in the present also, as in Figure 2 below.

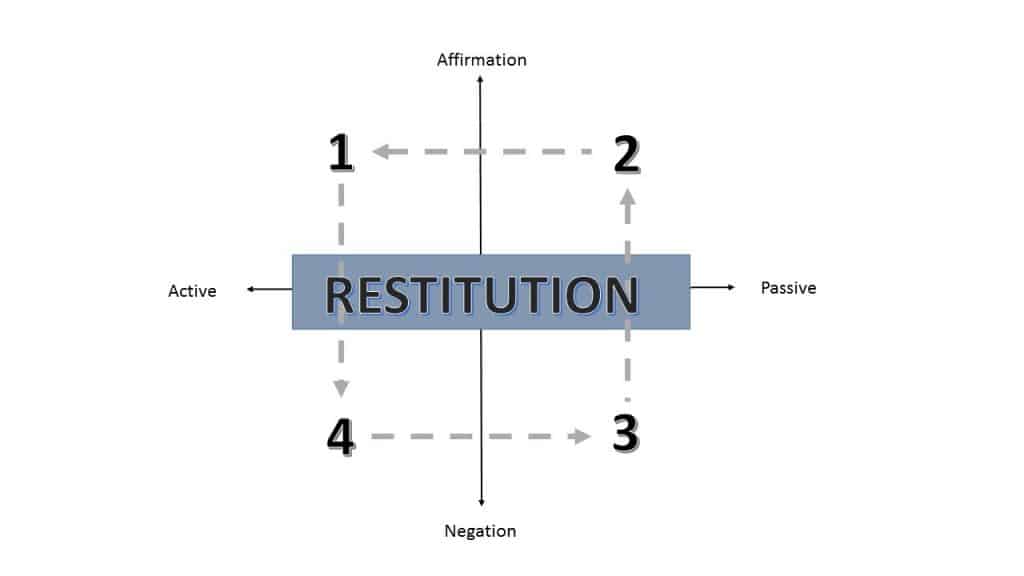

Fig. 2: Schema for Restitution and Reversal

Re-presentation as Restitution

To illustrate with a practical example. Many British cities have historic links with the slave trade and have often “honoured” prominent citizens with links to these difficult pasts in ways that celebrate them as benefactors without explicitly mentioning the origins of their wealth. The Liverpool slave trader James Penny, for example, is commemorated in “Penny Lane” and the Bristol slave trader, and leading figure in the Royal Africa Company, Edward Colston is “honoured” in a statue and in various other ways.[4] The Colston statue illustrates processes of restitution, whereby changes occur in the affirmative / negative presence of the past in public spaces. Colston was actively affirmed (Quadrant 1) by the citizens of Bristol in 1895, when they erected the statue, whose plaque reads “Erected by the citizens of Bristol as a memorial to one the most virtuous and wise sons of their city.” In recent years, the statue has been actively negated by protestors drawing attention to Colston’s role as a slave trader – the statue has been attacked with paint, has had items added to it (such as a blood red shackles) to symbolise Colston’s slave trading, and had a temporary installation erected in front of it, representing the captured Africans from whose enslavement Colston profited.[5] Finally, an additional plaque is in preparation that will officially acknowledge Colston as a slave trader noting, for example, that as “a high official of the Royal African Company” he played “an active role in the enslavement of over 84,000 Africans (including 12,000 children) of whom over 19,000 died en route to the Caribbean and America.”[6] These processes move the Colston statue from Quadrant 1 to Quadrant 4 – refunctioning its meaning.

Other processes can be modelled on the figure. James Penny’s lane, for example, no longer means what it did when it was named after him, having been the subject for a Beatles song (”Penny Lane”) through which it has come to signify, first, Lennon and McCartney’s nostalgic celebration of childhood and, second, contemporary nostalgic celebration of the Beatles era. James Penny was first forgotten, then, and finally overwritten through the affirmation of a different private and public past associated with The Beatles and their memory – a process that tends to obliviate Penny by instituting an alternative and separate narrative of Penny Lane – at least until campaigners for historical restitution remind us of the origin of the street’s name. [7]

Constituting – A Caveat

The talk of “hidden” histories that often accompanies campaigns to change public representations of the past often implies that the “hidden” stories they seek to tell have been present for centuries in repressed form and must now be uncovered. There is truth in this – we should not underestimate the importance of historical censorship. However, presenting such stories as merely waiting to be uncovered tends to understate the role that “constituting the past” plays in historical thinking and knowing.[8] Bourdieu praises the neo-Kantians’ emphasis on the “symbolic efficacy” of representations “in the construction of reality.”[9] His concepts “institution” and “destitution” sit well alongside Leon Goldstein’s concept of “historical constitution”, developed to contest “common sense… historical realism” by underlining the fact that “we have no access to the historical past except through its constitution in historical research.”[10] Those who contest “destitution” and argue for “restitution” are often advocating novel constructions of the past that challenge those generated by previous generations who drew on different cognitive resources and on differing values when constituting the pasts that they sought to institutionalise in their presents.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Bourdieu, Pierre. Language and Symbolic Power. Edited by John B. Thompson. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1991, 105-159.

- Goldstein, Leon. Historical Knowing. Austin and London: University of Texas Press, 1976, xvi-xxiii and 29-61.

Web Resources

- Emine Saner, “Renamed and shamed: taking on Britain’s slave-trade past, from Colston Hall to Penny Lane,” The Guardian, April 29 2017: https://www.theguardian.com/slave-trade-past-from-colston-hall-to-penny-lane (last accessed May 31 2019).

- Helena Horton, “Edward Colston plaque listing his links to slavery scrapped after mayor says wording isn’t harsh enough,” The Telegraph March 25 2019: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/plaque-acknowledging-slave-owning-history-edward-colston-scrapped/ (last accessed May 31 2019).

_____________________

[1] Oxford English Dictionary (n.d.) OED Online, http://www.oed.com (last accessed May 31 2019)

[2] I was privileged to present these ideas in the seminar series “Postkoloniale Perspektiven und die historisch-politische Bildung heute” in Basel in May 2017. I am grateful to Professor Marko Demantowsky for the invitation and to those attending the seminar for their comments and questions.

[3] Pierre Bourdieu, Language and Symbolic Power, ed. J. B. Thompson (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1991), 105-106.

[4] Emine Saner, “Renamed and shamed: taking on Britain’s slave-trade past, from Colston Hall to Penny Lane,” The Guardian April 29, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/apr/29/renamed-and-shamed-taking-on-britains-slave-trade-past-from-colston-hall-to-penny-lane (last accessed May 31 2019).

[5] Tristan Cork, “100 human figures placed in front of Colston statue in city centre,” Bristol Live October 18, 2018, https://www.bristolpost.co.uk/news/bristol-news/100-human-figures-placed-front-2122990 (last accessed May 31 2019).

[6] Martin Booth, “Proposed wording for new plaque on Colston statue revealed,” Bristol 24/7 July 17, 2018, https://www.bristol247.com/news-and-features/news/proposed-wording-new-plaque-colston-statue-revealed/ (last accessed May 31 2019).

[7] Lee Glendinning, “Renaming row darkens Penny Lane’s blue suburban skies,” The Guardian July 10, 2006, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2006/jul/10/arts.artsnews (last accessed May 31 2019).

[8] I borrow this term from Leon Goldstein, Historical Knowing (Austin and London: University of Texas Press, 1976).

[9] Pierre Bourdieu, Language and Symbolic Power, ed. J. B. Thompson (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1991, 105.

[10] Leon Goldstein, Historical Knowing (Austin and London: University of Texas Press, 1976), xvi-xxiii.

_____________________

Image Credits

Plaque for Robert Kett at Norwich Castle © 2019 Arthur Chapman.

Recommended Citation

Chapman, Arthur: On the Presences and Absences of Pasts. In: Public History Weekly 7 (2019) 24, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-14054.

Etymologie bildet ein faszinierendes Studienfeld, selbst wenn die Geschichte eines einzelnen Wortes nicht unbedingt etwas Wichtiges preisgibt über seine effektive Bedeutung in der Gegenwart. Kann die Etymologie, trotz ihrer Begrenzungen, unter der Oberfläche liegende Verbindungen zwischen Wörtern aufzeigen, Möglichkeiten zur Reflexion entfachen, und so vernachlässigte semantische Einsichten ermöglichen und explizit machen?

Stet – ‘lass es stehen’

Ziehen wir einmal die Wörter “Statue”, “Konstitution” und “Restitution” in Betracht. Alle teilen eine gemeinsame latinische Wurzel in “statuĕre, aufrichten, platzieren.”[1] Etwas, das konstituiert wird, wird “errichtet” und eingerichtet. “Restitution” schliesslich richtet etwas erneut auf – stellt einen Status wieder her, von dem gesagt wird, er hätte vor der Beschädigung bestanden, oder bevor ein Unrecht geschehen sei. “Stet” pflegte man zu schreiben – während man Textbeweise las – wenn man seine Meinung über eine Beseitigung änderte und, stattdessen, “diese stehen lassen” wollte. Diese Reflexionen kamen mir – vor einigen Jahren – beim Lesen einer Passage in Pierre Bourdieus Language and Symbolic Power. und sie schwingen in der gegenwärtigen Debatte und Massnahmen in Bezug auf das Errichten und/oder Entfernen von Statuen und Denkmälern mit und finden Ausdruck in der Gegenwartskultur beispielhaft dargestellt durch Kontroversen in Bristol, Charlottesville und anderswo.[2]

Destitution und Institution: Pierre Bourdieu

Bourdieu schreibt über “mehr oder weniger sozial abgestützte Handlungen von Institution und Destitution”, durch welche Individuen status-innehabende Prädikate zugeordnet (oder abgesprochen) werden. Er ist der Auffassung, dass solche Akte von Destitution/Institution helfen, “die Realität zu konstruieren” von der “Welt”, indem “geholfen wird, eine mehr oder weniger autorisierte Weise, die Welt zu sehen, einzuführen.”[3]

Bourdieus Wortgebrauch ist im Englischen unkonventionell – die Begriffe “Destitution” und “Institution” werden typischerweise als Nomen und Verben gebraucht und werden selten dazu benutzt, um auf solche Akte Bezug zu nehmen. Eine “Institution” – eine Schule, eine Universität, eine Kirche – findet oft einfach Erwähnung als etwas Gegebenes: mehr ein Rahmen, in dem Handlung stattfindet, weniger etwas, dessen permanentes Bestehen von einer fortdauernden sozialen Handlung abhängt. “Destitution” wird, in ähnlicher Weise, oft als Gegebenheit verstanden – wenn man von “Destituierten” spricht, um sich auf die Armen zu beziehen, meint man typischerweise diejenigen, die sich “in” einem Zustand von völliger Armut befinden und nicht, dass mögliche Akteur*innen von Destitution entsprechend “gehandelt” haben, um dieses Gegebenheit zu bewirken.

Bourdieu schematisieren

Destitution und Institution finden zweifellos auch Anwendung in Diskussionen über Geschichtskultur. Weshalb werden gewisse Erinnerungen, Ereignisse und historische Persönlichkeiten “instituiert” – manifestiert in Statuen, auf Straßenschildern, in Bibliotheken, in Schullehrplänen etc.? Weshalb werden wiederum andere Erinnerungen, Ereignisse und historische Persönlichkeiten “destituiert” – mit einer negativen Bedeutung versehen oder aktiv oder passiv aus den “Protokollen” gelöscht oder – im Falle von Statuen, deren Status neu bewertet werden – dem Erdboden gleichgemacht? Man kann sich Typologien vorstellen und Kontinua, welche entwickelt werden könnten, um Prozesse der “Destitution” und “Institution” verschiedener Art zu analysieren, wie unten in Abbildung 1 dargestellt.

Wir können zwischen Überresten und Darstellungen der Vergangenheit unterscheiden, welche aktiv bestätigt oder aktiv negiert werden – wie zum Beispiel Statuen, die aufgestellt (Quadrant 1 in der Abbildung) oder dekonstruiert (Quadrant 4 in der Abbildung) werden. Wir können auch zwischen Überresten und Darstellungen der Vergangenheit unterscheiden, welche einfach vorhanden sind und passiv erhalten werden (beispielsweise ein altes, immer noch genutztes Gebäude, welches noch den Namen seines Gründers trägt, welchen niemand bemerkt und an den sich niemand mehr erinnern kann [Quadrant 2]) oder passiv vernachlässigt werden (zum Beispiel ein Grabmal, welches vergessen gegangen ist und dessen Zerfall von niemandem verhindert wurde [Quadrant 3]). Zuweilen – wie auf unserem Bild von der Gedenktafel von Robert Kett auf der Mauer von Norwich Castle, wo er exekutiert wurde – können wir sogar von gleichzeitig stattfindender Institution und Destitution sprechen: Die Tafel “rettet” Kett davor, in Vergessenheit zu geraten, und feiert ihn als Helden im Kampf für soziale Gerechtigkeit und stellt gleichzeitig das Schloss als Werkzeug der Unterdrückung dar, welches dem Volk über Jahrhunderte ein “unterwürfiges Leben” aufgebürdet hatte. Diese Unterscheidungen können auch dazu genutzt werden, die Prozesse von Herausforderung und streitbarer Auseinandersetzung in der Gegenwart zu formen, wie unten in Abbildung 2:

Abb. 2: Schema für Restitution und Reversion

Re-präsentation als Restitution

Dies soll mit einem praktischen Beispiel illustriert werden. Vielen britischen Städten sind historische Verbindungen zum Sklavenhandel inhärent; Verbindungen, welche von diesen Städten dahingehend perpetuiert wurden, indem sie ihre prominenten Bürger*innen, die vom Sklavenhandel profitiert hatten, “geehrt” und als Wohltäter*innen gepriesen haben, ohne dass der Ursprung ihres Reichtums explizit erwähnt wurde. Dem Sklavenhändler James Penny aus Liverpool wird zum Beispiel durch “Penny Lane” gedacht und der aus Bristol stammende Sklavenhändler und führende Kraft in der Royal Africa Company, Edward Colston, wird durch eine Statue und auf verschiedene andere Arten “geehrt”.[4] Die Statue von Colston veranschaulicht Prozesse der Restitution, wobei Wechsel vorkommen in der affirmativen/negativen Präsenz der Vergangenheit in öffentlichen Räumen. Colston wurde durch die Bürger*innen von Bristol im Jahre 1895 aktive Affirmation zugestanden (Quadrant 1), als sie die Statue errichteten, auf deren Tafel zu lesen ist, “Aufgestellt von den Bürgern von Bristol als Erinnerungsstätte für einen der tugendhaftesten und klügsten Söhne der Stadt”. In den letzten Jahren hat die Statue dann aktive Negation von Demonstrant*innen erfahren, welche auf die Rolle von Colston als Sklavenhändler aufmerksam gemacht haben – die Statue wurde mit Farbe beworfen, ihr wurden Objekte angeheftet (wie zum Beispiel blutrote Fussketten), um Colstons Sklavenhandel zu symbolisieren, und vorübergehend wurde eine Installation davor hingestellt, welche die gefangenen Afrikaner*innen versinnbildlichte, aus deren Versklavung Colston Profit schlug.[5] Zu guter Letzt ist nun eine zusätzliche Tafel in Vorbereitung, welche Colston offiziell zum Sklavenhändler erklären und dem Publikum zur Kenntnis bringen wird, dass er “als hoher Funktionär der Royal Africa Company eine aktive Rolle in der Versklavung von über 84’000 Afrikaner*innen (mit eingeschlossen 12’000 Kinder), von denen über 19’000 en route zur Karibik und nach Amerika zu Tode kamen”, innehatte.[6] Diese Prozesse verschieben die Colston Statue von Quadrant 1 nach Quadrant 4 – dabei wird ihre Bedeutung umgewandelt.

Andere Prozesse können auf der Abbildung dargestellt werden. James Pennys Gasse (Penny Lane) hat zum Beispiel nicht mehr die Bedeutung, welche sie innehatte, als sie nach ihm benannt wurde, weil diese zum Gegenstand des gleichnamigen Beatles-Songs wurde, was Penny Lane neue Bedeutung zuschrieb: erstens Lennon and McCartneys nostalgische Verherrlichung der Kindheit und zweitens das gegenwärtige nostalgische Schwärmen für die Beatles-Ära. James Penny wurde zuerst vergessen, und schliesslich überschrieben durch die Affirmation einer anderen privaten und öffentlichen Vergangenheit, welche mit The Beatles und ihrer Erinnerung assoziiert wird. Dabei handelt es sich um einen Prozess, der dazu neigt, Penny in Vergessenheit geraten zu lassen, indem eine Alternative und ein eigenes Narrativ von Penny Lane instituiert wird – wenigstens bis die Aktivisten für historische Restitution uns den Ursprung des Strassennamens in Erinnerung bringen.[7]

Konstituieren – Ein Vorbehalt

Das Gerede von “unsichtbaren” Narrativen, welche nicht selten Kampagnen begleiten, die dazu dienen, die öffentlichen Darstellungen der Vergangenheit zu ändern, impliziert oft, dass die “unsichtbaren” Geschichten, auf welche es den Fokus zu legen sucht, in unterdrückter Form über Jahrhunderte vorhanden gewesen seien und jetzt ans Licht gebracht werden müssen. Darin steckt Wahrheit – wir sollten die Bedeutung von historischer Zensur nicht unterschätzen. Allerdings birgt das Darstellen von Geschichte, als ob sie einfach darauf wartete, entdeckt zu werden, die Gefahr, die Rolle, welche “das Konstituieren der Vergangenheit” im historischen Denken und Wissen spielt, als zu niedrig zu bewerten.[8] Bourdieu lobt, dass die Neukantianer die “symbolische Wirksamkeit” von Darstellungen “in der Konstruktion von Realität” betonen.[9] Seine Konzepte der “Institution” und der “Destitution” kommen Leon Goldsteins Konzept der “historischen Konstitution” sehr nahe, das entwickelt wurde, um den “gesunden Menschenverstand … den historischen Realismus” anzufechten, weil sie die Tatsache unterstreichen, dass “wir keinen Zugang zur historischen Vergangenheit haben, ausser durch deren Konstitution in der Geschichtsforschung.”[10] Diejenigen Wissenschaftler*innen, welche die “Destitution” anfechten und sich für die “Restitution” stark machen, plädieren oft für neuartige Konstruktionen der Vergangenheit, welche diejenigen, die von früheren Generationen geschaffen wurden, stark in Frage stellen; Generationen, die auf andere kognitive Ressourcen und unterschiedliche Werte zurückgriffen, als sie die Vergangenheiten konstituierten, welche sie in ihren Gegenwarten institutionalisieren wollten.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Bourdieu, Pierre. Language and Symbolic Power. Edited by John B. Thompson. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1991, 105-159.

- Goldstein, Leon. Historical Knowing. Austin and London: University of Texas Press, 1976, xvi-xxiii and 29-61.

Webressourcen

- Emine Saner, “Renamed and shamed: taking on Britain’s slave-trade past, from Colston Hall to Penny Lane,” The Guardian, April 29 2017: https://www.theguardian.com/slave-trade-past-from-colston-hall-to-penny-lane (letzter Zugriff 31. Mai 2019).

- Helena Horton, “Edward Colston plaque listing his links to slavery scrapped after mayor says wording isn’t harsh enough,” The Telegraph March 25 2019: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/plaque-acknowledging-slave-owning-history-edward-colston-scrapped/ (letzter Zugriff 31. Mai 2019).

_____________________

[1] Oxford English Dictionary (n.d.) OED Online, http://www.oed.com (letzter Zugriff 31. Mai 2019)

[2] Ich hatte das Privileg, diese Gedanken in der Seminarreihe “Postkoloniale Perspektiven und die historisch-politische Bildung heute” in Basel im Mai 2017 zu präsentieren. Professor Marko Demantowsky bin ich dankbar für die Einladung und den am Seminar Anwesenden für ihre Kommentare und Fragen.

[3] Pierre Bourdieu, Language and Symbolic Power, ed. J. B. Thompson (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1991), 105-106.

[4] Emine Saner, “Renamed and shamed: taking on Britain’s slave-trade past, from Colston Hall to Penny Lane,” The Guardian April 29, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/apr/29/renamed-and-shamed-taking-on-britains-slave-trade-past-from-colston-hall-to-penny-lane (letzter Zugriff 31. Mai 2019).

[5] Tristan Cork, “100 human figures placed in front of Colston statue in city centre,” Bristol Live October 18, 2018, https://www.bristolpost.co.uk/news/bristol-news/100-human-figures-placed-front-2122990 (letzter Zugriff 31. Mai 2019).

[6] Martin Booth, “Proposed wording for new plaque on Colston statue revealed,” Bristol 24/7 July 17, 2018, https://www.bristol247.com/news-and-features/news/proposed-wording-new-plaque-colston-statue-revealed/ (letzter Zugriff 31. Mai 2019).

[7] Lee Glendinning, “Renaming row darkens Penny Lane’s blue suburban skies,” The Guardian July 10, 2006, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2006/jul/10/arts.artsnews (letzter Zugriff 31. Mai 2019).

[8] Ich übernehme diesen Begriff von Leon Goldstein, Historical Knowing (Austin and London: University of Texas Press, 1976).

[9] Pierre Bourdieu, Language and Symbolic Power, ed. J. B. Thompson (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1991, 105.

[10] Leon Goldstein, Historical Knowing (Austin and London: University of Texas Press, 1976), xvi-xxiii.

_____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

Gedenktafel am Norwich Castle für Robert Kett © 2019 Arthur Chapman.

Übersetzung

Übersetzung Kurt Brügger swissamericanlanguageexpert

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Chapman, Arthur: Über die An- und Abwesenheit von Vergangenheiten. In: Public History Weekly 7 (2019) 24, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-14054.

Copyright (c) 2019 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 7 (2019) 24

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-14054

Tags: Language (Sprache), Monument (Denkmal), UK (Grossbritannien)