Abstract: The history of food and beverage offers many – often underestimated – public history opportunities. In a recent post, I explored how food history can help historians to connect and engage with local communities. Today, I want to share some recent experiences while teaching a class on public history and brewing practices.[1] I pertain that the history of beer and brewing practices is very rich and connects with larger socio-economic topics. Besides, researching beer and brewing traditions provides many opportunities for student to not only engage with popular audiences and non-traditional partners, but also forces them to reflect on the role of historians in contemporary societies.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-12940.

Languages: Français, English, Deutsch

L’histoire culinaire offre de nombreuses, et souvent sous-estimées, opportunités de faire de l’histoire publique. Dans un article précédent, je montrais en quoi l’histoire culinaire permettait d’impliquer les communautés locales. Je voudrais maintenant partager les expériences d’un cours d’histoire publique de la bière que j’enseigne ce semestre.[1] Je mets en avant que l’histoire de la bière est très riche et permet de mettre en avant de nombreux sujets culturels et socio-économiques. En outre, cette histoire permet aux étudiants non seulement de se confronter aux audiences non académiques, mais les force également à réfléchir aux rôles des historiens dans les sociétés contemporaines.

Un sujet riche et complexe

Un des défis principaux de la formation en histoire publique provient des multiples compétences à acquérir. Afin d’enseigner l’histoire publique, je propose souvent des sujets spécifiques en m’inspirant du patrimoine local. Habitant depuis peu au Colorado (États-Unis), j’ai vite réalisé que la bière et les brasseries étaient des thèmes de discussion très populaires. Ce semestre, j’offre donc un cours d’introduction à l’histoire publique qui se concentre sur l’essor de l’industrie de la bière. J’ai alors découvert un sujet passionnant.

L’histoire de la bière peut être reliée aux thèmes politiques, économiques, socio-culturels, et environnementaux. Des thèmes tels que la naissance de l’agriculture et des civilisations, la vie religieuse et monastique du Moyen-Âge, la modernisation des échanges commerciaux, la révolution industrielle, ou le phénomène migratoire au 19e siècle (notamment les brasseurs allemands qui furent à l’origine des brasseries Coors et Budweiser).[2] L’histoire de la bière est très utile pour combiner les approches globales et transnationales avec l’histoire quotidienne des communautés.

Éviter une histoire « allégée »

Dans un article sur les stratégies d’exposition au Colorado, Patty Limerick – ancienne historienne officielle de l’état du Colorado – regrettait la « légèreté » de la prochaine exposition sur l’histoire de la bière au Colorado, une historie célébrant plutôt que questionnant le passé.[3] Les bières, et en particulier les micro-brasseries, sont très populaires mais leur histoire peut être dénuée d’argumentation et d’analyse critique, se contentant de faire une liste d’événements et de succès, en délaissant des aspects les plus controversés et moins populaires tels que l’alcoolisme, les mouvements pro-prohibition, les discriminations sexuelles et ethniques, ou les dommages environnementaux. Cette histoire « allégée » pose des questions majeures sur le rôle des historiens. Que peuvent apporter les historiens à ces thèmes si populaires ?

Collaboration avec le secteur privé

Les collaborations et la participation du public sont deux critères centraux de l’histoire publique. Toutefois, travailler avec des compagnies à but lucratif pose certains problèmes. Comme l’expliquait Charlotte Bühl-Gramer dans son article « History Marketing Online » dans Public History Weekly, les politiques de marketing peuvent limiter l’histoire de l’entreprise aux aspects les plus favorables. Si les universités mettent en avant des objectifs éducatifs dans leurs formations, les compagnies à but lucratif ont d’autres priorités. Dans mon cours, il s’agit donc pour les étudiants de travailler avec les brasseries en tant que consultant historique et d’appliquer les méthodologies et compétences pour proposer des projets répondant aussi à la fois aux attentes commerciales et éducatives. Les étudiants doivent discuter avec leurs partenaires – ici les brasseries – afin de proposer des projets d’histoire publique et de gestion du patrimoine.

Les étudiants peuvent ainsi contribuer à la préservation des savoir-faire, un sujet parfois délaissé par les historiens. Les savoir-faire sont pourtant devenus un thème majeur de collaboration dans les trente dernières années. Par exemple, Economusée est une association née au Québec et regroupe artisans et spécialistes du patrimoine non seulement pour mettre en avant leurs travaux mais aussi pour préserver des pratiques traditionnelles. Le groupe Economusée explique « Les artisans portent par leurs métiers, l’histoire, les traditions et souvent une partie de l’identité culturelle d’un village, d’une région voire d’un pays. » Collaborer avec les brasseries dépasse la simple glorification de l’entreprise. Economusée affirme « L’artisan est, par sa capacité à préserver un patrimoine immatériel, un atout indispensable à la sauvegarde et à la promotion d’un savoir-faire identitaire contribuant ainsi au rayonnement des cultures dans un monde globalisé. »[4] Les étudiants apprennent à collaborer avec des artisans et des sites de production pour préserver et interpréter un patrimoine culturel.

Travailler avec les brasseries nécessite également pour les étudiants de réfléchir à la place et aux usages de l’histoire dans nos sociétés. Que peuvent apporter les historiens ? Il est nécessaire de replacer l’histoire de l’entreprise dans une histoire plus large et plus complexe. Par exemple, l’histoire d’une brasserie peut être reliée aux réseaux agricoles et aux multiples intermédiaires de la chaine de production, ainsi qu’à l’histoire du territoire – approvisionnement en eau potable – ou les débats sur la prohibition face aux droits des individus. En élargissant l’histoire de l’entreprise, les étudiants questionnent le passé et les conceptions contemporaines d’un sujet populaire.

L’apprentissage du métier d’historien

Grâce aux formations d’histoire publique, les étudiants acquièrent de nouvelles compétences. Écrire pour des publics non-académiques (panneaux d’histoire de l’entreprise dans les brasseries), interpréter le passé grâce aux objets, ou communiquer l’histoire par l’intermédiaire d’une visite guidée permet aux étudiants de travailler avec le public. Les étudiants discutent également des défis que soulève la collaboration avec des partenaires non académiques. Les historiens peuvent ainsi collaborer avec des archéologues, des chimistes, des brasseurs pour recréer des anciennes recettes de bières. Par exemple, Pat McGovern est en charge du projet d’archéologie biomoléculaire pour la cuisine et les boissons fermentées au sein du Musée de l’Université de Pennsylvanie, et a collaboré avec des historiens, des anthropologues, et la populaire brasserie Dogfish Head pour recréer – dans une forme d’archéologie expérimentale – une bière vieille de plus de 4000 ans.[5] L’approche historique est ici cruciale non seulement pour retrouver mais également pour questionner les différents types d’archives amenant à la conception de la recette.

_____________________

Lectures supplémentaires

- Mittelman, Amy. Brewing Battles: A History of American Beer. New York: Algora Publishing, 2007.

- Meussdoerffer, Franz G.. “A Comprehensive History of Beer Brewing”. In Handbook of Brewing: Processes, Technology, Markets, edited by Hans Michael Eßlinger. London: Wiley, 2009.

Resources sur le web

- Smithsonian National Museum of American History, “Brewing History”: http://americanhistory.si.edu/brewing-history (last accessed 13 September 2018).

- Europeana Collections: https://www.europeana.eu/portal/ (last accessed 13 September 2018).

_____________________

[1] Thomas Cauvin: “Personal Page” https://history.colostate.edu/author/tcauvin/ (last accessed 1 October 2018).

[2] Mark Benbow, “German Immigrants in the United States Brewing Industry (1840-1895),” in German Historical Institute February 2017, http://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entry.php?rec=284 (last accessed 1 October 2018).

[3] Patty Limerick, “Prodding a historic friend to do better,” Denver Post, July 23, 2018, https://www.denverpost.com/2018/07/13/history-colorado/ (last accessed 1 October 2018).

[4] Economusée “Our Purpose”, https://www.economusees.com/en/about-us/our-purpose (last accessed 1 October 2018).

[5] Abigail Tucker, “The Beer Archaeologist,” Smithsonian Magazine, August 2011, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-beer-archaeologist-17016372/ (last accessed 1 October 2018).

_____________________

Crédits illustration

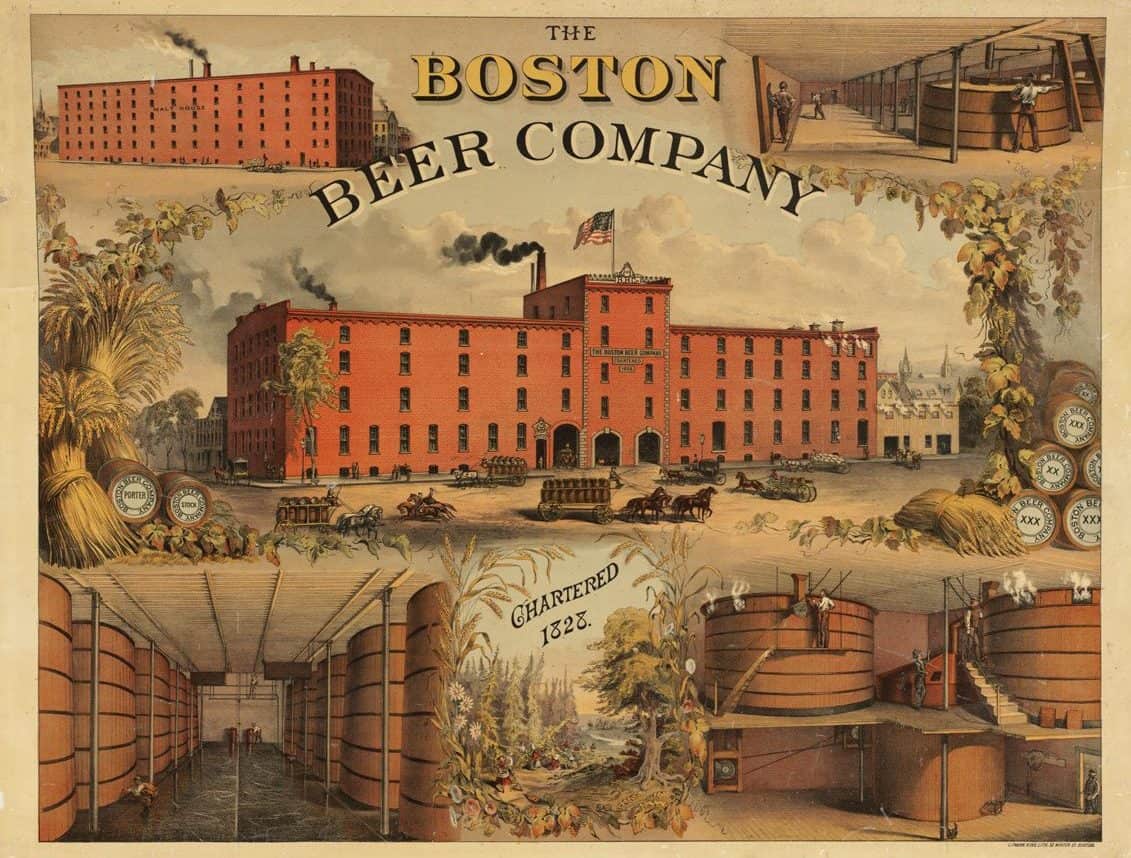

The Boston Beer Company, chartered 1828 © Boston Public Library, CC BY 2.0.

Citation recommandée

Cauvin, Thomas: Bières, Brasseries, et Histoire Publique. In: Public History Weekly 6 (2018) 36, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-12940.

The history of food and beverage offers many – often underestimated – public history opportunities. In a recent post, I explored how food history can help historians to connect and engage with local communities. Today, I want to share some recent experiences while teaching a class on public history and brewing practices.[1] I pertain that the history of beer and brewing practices is very rich and connects with larger socio-economic topics. Besides, researching beer and brewing traditions provides many opportunities for student to not only engage with popular audiences and non-traditional partners, but also forces them to reflect on the role of historians in contemporary societies.

A (surprisingly) challenging topic

One of the challenges for public history training comes from the multiple fields and skills that students should acquire. In order to teach public history, I propose topics on which to apply those skills. I usually turn to the local communities for inspiration. Having recently moved to Colorado (USA), I quickly realized that beers and brewing traditions are very popular topics of discussion. Therefore, this semester I offer one Introduction to Public History course that focuses on the history of beer and brewing in Colorado. While trendy, I did not expect the topic to be so rich and complex.

Beer history is actually a topic one can use to teach political, economic, social, cultural, or environmental history. Brewing has been connected, among other fields, to agriculture and the rise of civilization, religious life in the Middle-Ages (through monasteries), the modernization of transportation and exchanges in the early modern period, the industrial revolution and innovation, and immigration (like German brewers setting up breweries like Coors or Budweiser in the United States)[2]: Beer history is a perfect topic to research both large phenomena (immigration) and everyday life (saloons and public space).

Avoiding a “Lite” History

In a recent article about exhibiting policy in Colorado, former state historian Patty Limerick regretted that the forthcoming exhibition on the history of beer in Colorado was more what she called “history lite and effervescent”, a sort of celebratory and uncritical narrative.[3] Working on popular topics is indeed challenging. Beers – especially craft beers – and breweries are popular topics but their history often remains devoid of argumentation and often limit themselves to lists of events, successes and accomplishments and leave aside more controversial and sensitive topics such as anti-alcohol campaigns, drug addiction, segregation (ethnic and gender) over public behaviors, or environmental pollution. This raises questions about the role of historians while working with the public. What do historians add to popular stories?

Collaboration with For-Profit Companies

Collaboration and public participation are key aspects of public history. However, working with for-profit companies like breweries raises specific challenges. As recently discussed in Charlotte Bühl-Gramer’s article on “History Marketing Online” in Public History Weekly, marketing often ends up in placing “the organization in a favourable light.” Whether universities and schools have educational objectives, for-profit companies have financial and marketing rationales. In my course, I asked students to work with breweries and brewers’ associations as if they were historical consultants proposing projects. Students have to meet and discuss the needs from the breweries in terms of history and heritage management and come up with proposals.

In doing so, students contribute to preserving how-to and traditional practices. This has become a popular field of collaboration in the last three decades. For instance, Economusée is an association that has grouped artisans in Canada – and now in many European countries too – to not only showcase their work but also to preserve traditional practices. Economusée explains that “We believe that through their trades, artisans perpetuate history, tradition and often even a part of the cultural identity of a village, region or country.” Working with breweries is likewise much more than celebrating a company. According to the concept of Economusée, we can assert that “Through their ability to preserve an intangible heritage, artisans are vital contributors to promoting and safeguarding identitarian forms of knowledge that contribute to cultural outreach in a globalized world.”[4] Students learn how they can use and collaborate with artisan and production sites to preserve cultural heritage and communicate historical practices.

This constant relation with breweries also forces my students to reflect upon the use of historical methodology in present-day societies, as well as what they could bring as historians. It is crucial to set the company into a longer and broader context and avoid the traditional self-centered success stories narratives proposed by companies. For instance, the history of breweries should connect to the local agricultural networks, the history of water and land uses, as well as the long term discussions on prohibition versus civil liberties. Broadening the context of interpretation makes the past more meaningful for audiences and help connecting the breweries to local communities.

Student Learning Process

Through this public history training, students acquire new skills such as writing for non-academic audiences – writing panels for breweries – researching and making history through objects – mounting a self-guided tour with brewing tools – or communicating history through a guided-tour (their final project of the semester). Perhaps more importantly than skills, students also reflect upon the assets and challenges of collaboration with non-traditional partners in interdisciplinary projects. Historians, archaeologists, chemists, (home)brewers can work together to (re)create old beers. For instance, Dr. Pat McGovern has run the Biomolecular Archaeology Project for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health at the University of Pennsylvania Museum and collaborated with historians, anthropologists and the Dogfish Head brewery to recreate – in a sort of experimental archaeology – a 4,000 year old beer.[5] Historical methodology is key not only to research archives but also to critically engage with traces from the past.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Mittelman, Amy. Brewing Battles: A History of American Beer. New York: Algora Publishing, 2007.

- Meussdoerffer, Franz G.. “A Comprehensive History of Beer Brewing”. In Handbook of Brewing: Processes, Technology, Markets, edited by Hans Michael Eßlinger. London: Wiley, 2009.

Web Resources

- Smithsonian National Museum of American History, “Brewing History”: http://americanhistory.si.edu/brewing-history (last accessed 13 September 2018).

- Europeana Collections: https://www.europeana.eu/portal/ (last accessed 13 September 2018).

_____________________

[1] Thomas Cauvin: “Personal Page” https://history.colostate.edu/author/tcauvin/ (last accessed 1 October 2018).

[2] Mark Benbow, “German Immigrants in the United States Brewing Industry (1840-1895),” in German Historical Institute February 2017, http://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entry.php?rec=284 (last accessed 1 October 2018).

[3] Patty Limerick, “Prodding a historic friend to do better,” Denver Post, July 23, 2018, https://www.denverpost.com/2018/07/13/history-colorado/ (last accessed 1 October 2018).

[4] Economusée “Our Purpose”, https://www.economusees.com/en/about-us/our-purpose (last accessed 1 October 2018).

[5] Abigail Tucker, “The Beer Archaeologist,” Smithsonian Magazine, August 2011, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-beer-archaeologist-17016372/ (last accessed 1 October 2018).

_____________________

Image Credits

The Boston Beer Company, chartered 1828 © Boston Public Library, CC BY 2.0.

Recommended Citation

Cauvin, Thomas: Brewing History as a Public Experience.. In: Public History Weekly 6 (2018) 36, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-12940.

Die Geschichte des Essens und Trinkens bietet der Public History viele, oftmals unterschätzte Möglichkeiten. In einem meiner früheren Beiträge habe ich ausgeführt, wie Historiker*innen durch die Geschichte des Essens mit der lokalen Bevölkerung in Interaktion treten können. Hier möchte ich einige Lehrerfahrungen aus einem Public-History-Seminar über Brauereipraktiken anführen.[1] Die Geschichte des Bieres und der Brautraditionen ist sehr vielfältig und mit übergeordneten sozio-ökonomischen Themen verknüpft. Die Beschäftigung mit Brauereitraditionen ermöglicht es den Student*innen außerdem, mit nichtakademischen Öffentlichkeiten und untypischen Partner*innen in Kontakt zu treten und die Rolle der Historiker*innen in der gegenwärtigen Gesellschaft zu reflektieren.

Ein (erstaunlich) anspruchsvolles Thema

Eine der Herausforderungen der Public History sind die vielfältigen Fähigkeiten und Themen, die die Studierenden lernen und beherrschen sollen. Um Public History zu vermitteln, biete ich Themen an, bei denen diese Fähigkeiten Anwendung finden können.

Als Inspirationsquelle dient mir meistens die lokale Bevölkerung. Als ich vor kurzem nach Colorado (USA) zog, bemerkte ich, dass Biersorten und Brautraditionen ein sehr beliebtes Diskussionsthema sind. Folglich konzentriert sich mein aktuelles Einführungsseminar in die Public History auf die Geschichte des Brauereiwesens in Colorado. Obwohl offensichtlich ein modisches Thema, hatte ich nicht erwartet, dass es sich als derart weitreichend und komplex erweisen würde. Anhand der Brauereigeschichte lassen sich Politik-, Wirtschafts-, Sozial-, Kultur- und Umweltgeschichte thematisieren. Das Brauereiwesen ist unter anderem verknüpft mit Aspekten der Landwirtschaft und des Aufstiegs von Zivilisationen, dem religiösen Leben im Mittelalter (Kloster), der frühneuzeitlichen Modernisierung des Transport- und Handelswesens, der Industriellen Revolution und der Immigration (etwa deutscher Bierbrauer, die in den Vereinigten Staaten die Brauereien Coors und Budweiser gründeten)[2]: Brauereigeschichte ist ein dankbares Thema, um langwellige Phänomene wie Immigration und zugleich Alltägliches wie Bars und den öffentlichen Raum zu thematisieren.

Ohne “Light“-Versionen

Kürzlich bedauerte die frühere offizielle Historikerin des Bundesstaates Colorado, Patty Limerick, in ihrem Artikel über Colorados Ausstellungswesen, dass eine anstehende Ausstellung über die Geschichte des Bieres in Colorado eine lediglich “spritzig-süffige Angelegenheit“ sei, mit einem rein lobenden, unkritischen Narrativ.[3] Es ist tatsächlich eine Herausforderung, modische Themen zu bearbeiten. Biere – insbesondere Craft-Biere – und Brauereien sind äußerst beliebte Themen, aber ihre Historiographien bleiben oft oberflächlich und beschränken sich auf eine Auflistung von Ereignissen, Errungenschaften und Erfolgen. Kontroversere und sensiblere Aspekte wie Anti-Alkohol-Kampagnen, Drogenmissbrauch, Rassen- und Geschlechtertrennung oder Umweltverschmutzung werden ausgelassen. Dies wirft die Frage auf, welche Rolle Historiker*innen im Kontakt mit der Öffentlichkeit zukommt. Was können Historiker*innen zu populären Erzählungen beisteuern?

Zusammenarbeit mit profitorientierten Firmen

Zusammenarbeit mit und Teilhabe an der Öffentlichkeit sind Schlüsselelemente der Public History. Die Zusammenarbeit mit an Gewinn orientierten Firmen wie etwa Brauereien, birgt besondere Herausforderungen. Wie Charlotte Bühl-Gramer unlängst in ihrem Artikel “History Marketing Online“ auf Public History Weekly anmerkte, läuft das Firmenmarketing oft darauf hinaus, das Unternehmen “massenwirksam zu inszenieren“. Während Universitäten und Schulen didaktische Ziele verfolgen, richten sich Unternehmen nach finanziellen Fragen und Marktanforderungen aus. Ich habe meine Studierenden gebeten, in der Zusammenarbeit mit Brauereien und Brauereigesellschaften wie historische Unternehmensberater*innen aufzutreten, die diesen Projektideen unterbreiten. Die Studierenden müssen sich treffen, die Wünsche der Brauereien hinsichtlich der Darstellung ihrer Firmengeschichte und des historischen Erbes besprechen und Vorschläge entwickeln. Dadurch tragen die Studierenden zur Sicherung von Wissen und Brautraditionen bei. In den letzten drei Jahrzehnten hat sich dies zu einer beliebten Kooperationsform entwickelt. Beispielsweise ist das Economusée eine Gesellschaft, die Handwerker in Kanada – und nun auch in vielen europäischen Ländern – vereint, um nicht nur ihre Erzeugnisse zu präsentieren, sondern auch Handwerkstraditionen zu sichern. Economusée erklärt, dass sie “glauben, dass Handwerker und Künstler durch ihren Handel, Vergangenes, Traditionen und oft sogar die kulturelle Identität eines Dorfes, einer Region oder eines Landes verewigen“. Die Zusammenarbeit mit Brauereien ist gleichfalls vielmehr als die Lobpreisung eines Unternehmens. Wie Economusée vertrete auch ich die Ansicht, dass “Handwerker*innen durch ihre Fähigkeit, immaterielles Erbe zu erhalten, entscheidend zu Verbreitung und Erhalt identitätsstiftenden Wissens beitragen“.[4] Studierende erlernen, wie sie nutzbringend mit Handwerker*innen und Produktionsstätten zusammenarbeiten können, um kulturelles Erbe zu erhalten und historische Praktiken weiter zu vermitteln.

Der stete Kontakt mit Brauereien zwingt meine Studierenden außerdem dazu, über die Anwendung geschichtswissenschaftlicher Methodologie auf die gegenwärtige Gesellschaft sowie über ihren Beitrag als Historiker*innen nachzudenken. Es ist notwendig, das Unternehmen in einem breiteren Kontext zu verorten und das klassische selbstzentrierte Erfolgsnarrativ zu vermeiden, das Firmen anbieten. Beispielsweise sollten Brauereigeschichten an lokale landwirtschaftliche Netzwerke anknüpfen, an die Geschichte der Wasser- und Landnutzung und an langfristige Diskussionen über Prohibition und bürgerliche Freiheiten. Durch die Erweiterung des Interpretationsrahmens gewinnt die Vergangenheit an Bedeutung und hilft, Brauereien mit der lokalen Bevölkerung in Verbindung zu bringen.

Lernprozesse der Studierenden

Dank eines solchen Public-History-Kurses erlangen Studierende neue Fähigkeiten wie etwa das Schreiben von populärwissenschaftlichen Texten – durch das Verfassen von Ausstellungstafeln für Brauereien –, das Erforschen und Vermitteln der Vergangenheit anhand von Objekten – durch die Konzeption eines Lehrpfads entlang der vorhandenen Geräte – oder die Vermittlung von Geschichte durch eine Brauereiführung (ihre Semesterabschlussarbeit). Noch wichtiger als die vermittelten Fähigkeiten ist vielleicht die Tatsache, dass sich Studierende mit den Möglichkeiten und Schwierigkeiten einer solchen Zusammenarbeit mit ungewöhnlichen Partnern in interdisziplinären Projekten auseinandersetzen. Historiker*innen, Archäolog*innen, Chemiker*innen und (Hobby-)Bierbrauer*innen können zusammenarbeiten, um alte Biersorten (wieder)herzustellen. Beispielsweise hat Dr. Pat McGovern das Biomolekulare Archäologieprojekt für Küche, Gärgetränke und Gesundheit des University of Pennsylvania Museums geleitet und dabei mit Historiker*innen, Anthropolog*innen und der Dogfish Head Brauerei in einer Art archäologischem Experiment ein über 4000 Jahre altes Bier rekonstruiert.[5] Die Methoden der Geschichtswissenschaft dienen nicht nur der Forschung in Archiven, sondern auch der kritischen Auseinandersetzung mit Relikten aus der Vergangenheit.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Mittelman, Amy. Brewing Battles: A History of American Beer. New York: Algora Publishing, 2007.

- Meussdoerffer, Franz G.. “A Comprehensive History of Beer Brewing”. In Handbook of Brewing: Processes, Technology, Markets, edited by Hans Michael Eßlinger. London: Wiley, 2009.

Webressourcen

- Smithsonian National Museum of American History, “Brewing History”: http://americanhistory.si.edu/brewing-history (letzter Zugriff 13. September 2018).

- Europeana Collections: https://www.europeana.eu/portal/ (letzter Zugriff 13. September 2018).

_____________________

[1] Thomas Cauvin: “Personal Page” https://history.colostate.edu/author/tcauvin/ (letzter Zugriff 1. Oktober 2018).

[2] Mark Benbow, “German Immigrants in the United States Brewing Industry (1840-1895),” in German Historical Institute February 2017, http://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entry.php?rec=284 (letzter Zugriff 1. Oktober 2018)).

[3] Patty Limerick, “Prodding a historic friend to do better,” Denver Post, July 23, 2018, https://www.denverpost.com/2018/07/13/history-colorado/ (letzter Zugriff 1. Oktober 2018)).

[4] Economusée “Our Purpose”, https://www.economusees.com/en/about-us/our-purpose (letzter Zugriff 1. Oktober 2018)).

[5] Abigail Tucker, “The Beer Archaeologist,” Smithsonian Magazine, August 2011, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-beer-archaeologist-17016372/ (letzter Zugriff 1. Oktober 2018)).

_____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

The Boston Beer Company, chartered 1828 © Boston Public Library, CC BY 2.0.

Übersetzung

Maria Albers

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Cauvin, Thomas: Brauereigeschichte als gemeinschaftliche Erfahrung. In: Public History Weekly 6 (2018) 36, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-12940.

Copyright (c) 2018 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 6 (2018) 36

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-12940

Tags: Food History (Geschichte des Essens), Language: French, University teaching (Hochschuldidaktik), USA

To all our non-English speaking readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator. Just copy and paste.

The Reinheitsgebot in Public History

The Reinheitsgebot, or German Purity Law, is considered to be the oldest consumer protection law of the world. Released in 1516 by the Bavarian duke Wilhelm IV.[1], it can be regarded through the ages. As Thomas Cauvin focused on the local breweries in Colorado, the Reinheitsgebot is also worth being analyzed in a political, an economic, a social, a cultural or an environmental view. With more than 500 years of history, it is a gift to make topics like this more interesting on the one hand for students, on the other hand for the publicity in regard of public history.

In 2016 the Reinheitsgebot celebrated its 500th anniversary. The public history of this event was dominated by the German Brewer Union, who created a website and even a corporate video in German and in English, to demonstrate the power of this tradition.[2] Core of this self-expression is, that the Reinheitsgebot claims to be a seal of quality throughout its existence. The exposure can be criticized the same way Patty Limerick criticized the exhibition of the Colorado beer. In Germany, it was a self-adulation, which played a lot with the emotional part of tradition and the regional origin of beer and its raw materials. Beer in Germany is real, it is handcraft, it is art.[3] This is the German Brewer Union’s quite romantic view on a law, which limits the brewers nowadays and limited them back in time.

However, this branding of German beer is no invention of Wilhelm IV. of Bavaria. It came up in the last 50 years to protect the German market from foreign beers. A propaganda started, which labeled non-German beers as impure. This strategy even brought the EC-commission to intervene and declare this procedure as wrong.[4] Here we have one example in a 500-year history, which can be regarded under several aspects. A focus could be on EU-legislation, the economy in Germany, and so on. This example points out the complexity of something in Germany as present and accepted as the Reinheitsgebot. Studies could be also made about the diction of the German Purity Law. It is called nowadays rather “German Purity Commandment”, because of the latent ambiguity with “Purity Law” during the National Socialism. Another possible research could be engaged in the Middle Ages. Wheat was no ingredient of German beer, because it should be used to bake bread.[5] But why did some breweries earn the privilege to brew weiss bier with this valuable grain?

Thus, are the achievements of the Reinheitsgebot just a romantic lie advertised well by the German Brewer Union? I think, like Thomas Cauvin said, that history of food and drinks, especially traditional alcoholic beverages, have a high potential to be examined in a university context. The romantic view of the Reinheitsgebot is so present in Germany, and beer is such a commonplace part of life, that consternation can be easily created. There is a base, from which students as well as pupils, in a school context, can develop questions about the law itself, brewing history, limits of the law, and so on. Framed in a seminar, these problems can be solved with the steps of historical learning and lead to a historical based opinion.[6]

From my point of view, I worked for four years part-time in a Bavarian beer garden with an own brewery, the step of students into breweries is quite interesting. I saw how Bavarian brewers adhere on the Reinheitsgebot and advertise every bottle they sell with the date of its approval. Tradition plays a very important role in handicraft businesses and is part of their identity. However, I think a destruction of historical guidelines like this is not the way public history should be made. But working together can put the misty-eyed view on the Reinheitsgebot besides, point out problems the law made or limitations it brought, and make a new branding with the handicraft tradition on the one hand and the critical review on the other hand. By involving the companies in the re-branding of their brewery and stating out the achievements they made with the Reinheitsgebot, it can lead to a more critical view on the oldest consumer protection law of the world. Hence, the students have to face the transfigured view of German brewers, step back from their academic view on the case and involve historical methods to influence public history by cooperating with regional nationwide partners with a way higher range.

References

[1] Deutscher Brauer-Bund (Ed.): Verbriefte Reinheit, https://www.reinheitsgebot.de/startseite/reinheitsgebot/entstehung/ (last accessed January 28th 2019).

[2] Deutscher Brauer-Bund (Ed.): Unser Reinheitsgebot, https://www.reinheitsgebot.de/startseite/ (last accessed January 28th 2019).

The German image film of the Reinheitsgebot:

Deutscher Brauer-Bund (Ed.): Das Reinheitsgebot – der Film – 500 Jahre Braukunst und Biervielfalt, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q7S4jVrsWww (last accessed January 28th 2019).

[3] Deutscher Brauer-Bund (Ed.): German purity law for beer – The Reinheitsgebot, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T2MHLuINZGM (last accessed January 28th 2019).

[4] Conrad Seidl: 500 Jahre Reinheitsgebot: von wegen Einheitsgebot, https://derstandard.at/2000032650574/500-Jahre-ReinheitsgebotVon-wegen-Einheitsgebot (last accessed January 28th 2019).

[5] Conrad Seidl: 500 Jahre Reinheitsgebot: von wegen Einheitsgebot, https://derstandard.at/2000032650574/500-Jahre-ReinheitsgebotVon-wegen-Einheitsgebot (last accessed January 28th 2019).

[6] Peter Gautschi, Jan Hodel, Hans Utz: Kompetenzmodell für „Historisches Lernen“ – eine Orientierungshilfe für Lehrerinnen und Lehrer, http://ernst-goebel.hoechst.schule.hessen.de/fach/geschichte/material_geschichte/allpaed_geschichte/kompetenzorientierunggu/litkompetenzorientierunggu/Gautschi-Kompetenzmodell_fuer_historisches_LernenAug09.pdf (last accessed January 28th 2019), S. 5-7.