Abstract: In a lesson on Belgian history, a teacher mentions: “And we have the most progressive constitution of Europe in 1831, meaning some countries did not have those rights yet. In Russia, serfdom still existed. Farmers were the property of the nobility.” A history textbook chapter on Japan under the Meiji (1867-1912) starts as follows: “19th century Japan was still characterized by feudalism.” Another textbook, dealing with the Ancien Régime, stresses that from the 14th century onwards, in Western Europe serfdom disappeared, while in Eastern Europe serfdom was by contrast reinforced.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-8597

Languages: Dutch, English, Deutsch

In een les over Belgische geschiedenis, stelt een leerkracht: “En wij zijn de meest moderne grondwet van Europa in 1831, dus in andere landen was dat er soms nog niet. Mannen, in Rusland was er nog lijfeigenschap. Behoorden boeren met lijf en leden aan de adel, dat bestond nog.” Een leerboekhoofdstuk getiteld Japan onder de Meiji (1867-1912) opent als volgt: “In 1850 was Japan nog een feodale staat.” Een ander leerboek, over het Ancien Régime, benadrukt dat vanaf de 14e eeuw het lijfeigenschap in West-Europa gradueel verdween, terwijl het in Oost-Europa net versterkt werd.

Een Eurocentrische benadering

Tezelfdertijd negeert het de progressieve politiek van religieuze verdraagzaamheid van de Poolse koning Casimir in de 14e eeuw, die de privilegies en bescherming eerder aan Joden toegekend, bevestigde, en hen aanmoedigde zich in Polen te vestigen (nadat ze uitgewezen waren uit Engeland en Frankrijk). Deze voorbeelden leggen expliciet de erg West-Europees georiënteerde eurocentrische benadering van het verleden bloot. Eurocentrisme in geschiedenisonderwijs verwijst naar twee zaken: (1) een geschiedeniscurriculum dat vooral aandacht besteedt aan (West-)Europese geschiedenis, (West-)Europa in het centrum van de wereldgeschiedenis plaatst, en enkel aan (West-)Europeanen en bij uitbreiding aan Westerlingen agency toekent in het verleden, en (2) het gegeven dat (West-)Europa hoger wordt geacht dan en als maatstaf dient om andere beschavingen aan af te meten, en te beoordelen.

Voornoemde voorbeelden reflecteren de sterke eurocentrische oriëntatie van het geschiedeniscurriculum in Vlaanderen. Dat curriculum lijkt te suggereren dat de belangrijkste ontwikkelingen in de wereldgeschiedenis te vinden zijn in de evolutie van de Europese (en westerse) wereld, gekenmerkt door een geleidelijke maar gestage opgang naar meer democratie en vrijheid. Op die wijze vormt het curriculum een nieuwe articulatie van de tegenstelling die in de 19e eeuw al werd gecreëerd tussen the West and the rest.[1]

Deze eurocentrische benadering draagt belangrijke implicaties in zich, zeker wanneer we de belangrijkste doelstellingen van het Vlaamse geschiedenisonderwijs in acht nemen. Enerzijds wordt van geschiedenisonderwijs verwacht dat het leerlingen introduceert in de academische discipline geschiedenis. Anderzijds moet het leerlingen voorbereiden op hun rol “als lid van de samenleving”, wat onder meer inhoudt dat het leerlingen moet ondersteunen in hun proces van identiteitsvorming. Het curriculum schuift daarbij geen (sub)nationale identiteit naar voor. Integendeel is het basisreferentiekader Westers (Europees) georiënteerd.[2]

Gevolgen van het eurocentrisme

Wat zijn dan die implicaties precies? Eerst en vooral komt de West-Europees georiënteerde eurocentrische benadering van het verleden niet tegemoet aan de verwachting om leerlingen te introduceren in de academische historiografie, op twee niveaus.

(1) Het belemmert een genuanceerd en breed begrip van het verleden. Door enkel te focussen op West-Europa, en andere delen van Europa en bij uitbreiding de wereld te negeren, biedt deze benadering slechts een beperkte, enge en eenzijdige representatie van het verleden. Bovendien wekt het de verkeerde indruk dat West-Europa zich altijd situeerde in de kern van de menselijke beschaving en “dus” als maatstaf kan dienen om andere beschavingen aan af te meten.

(2) Daarenboven belemmert eurocentrisme de competentie van leerlingen om historisch te denken. Het in acht nemen van meerdere perspectieven, en de analyse van uiteenlopende historische bronnen afkomstig van verschillende actoren, is immers grotendeels afwezig in een eurocentrische benadering, net als een reflectie op de agency van staten, volkeren, groepen en individuen van verschillende origine. Leerboeken negeren bv. compleet de rol van het Pools-Litouwse Gemenebest – toentertijd nochtans een van de grootste en meest bevolkte staten van Europa – in het Europa van de vroegmoderne tijd. Ook negeren ze grotendeels (elke agency van) de inheemse volkeren in hun relaas over het 19e eeuwse modern imperialisme.[3]

De afwezigheid van niet-West-Europese stemmen uit het verleden sluit nauw aan bij een tweede belangrijke implicatie, voor de identiteitsvorming van leerlingen. De eurocentrische suggestie dat West-Europa altijd het kerngebied van de menselijke beschaving vormde, kan aanleiding geven tot de vorming van een superioriteitsgevoel. Jongeren in Vlaanderen, behorend tot de blanke meerderheidsgroep, kunnen zo de indruk krijgen dat “hun” cultuur superieur was en is aan elke andere cultuur. Een dergelijk denken leidt vervolgens makkelijk naar een wij-zij denken en een exclusief en uitsluitend proces van identiteitsopbouw. Eerder onderzoek toonde al aan dat een dergelijk mechanisme zich effectief voordoet.[4] Jongeren behorend tot een minderheidsgroep, anderzijds, dreigen zich niet thuis te voelen in een geschiedenisonderwijs dat elke niet-West-Europese cultuur als “achter” beschouwt; op die manier dreigen ze te vervreemden van de huidige samenleving.[5]

Multiperspectiviteit

De vraag rijst dan hoe een West-Europees georiënteerde eurocentrische benadering kan worden doorbroken. Het insluiten van multiperspectiviteit in het geschiedenisonderwijs lijkt een vruchtbare strategie te zijn, die kan ingezet worden op inhoudelijk zowel als didactisch vlak. Op het inhoudelijke niveau stimuleert multiperspectiviteit om andere perspectieven en geschiedenissen dan alleen maar West-Europese te integreren. Dit kan gerealiseerd worden door bv. te focussen op interculturele contacten – als belangrijke motor van verandering in het verleden[6] – of op migratiestromen. Beide benaderingen sluiten per definitie meer dan alleen West-Europese samenlevingen in. Tezelfdertijd vermijden ze de valkuil van een centrumloze wereldgeschiedenis-benadering van het verleden, die het risico in zich draagt dat geschiedenis betekenisloos wordt voor leerlingen in Vlaanderen, bij gebrek aan enige connectie met hun situering in het heden.

Op een didactisch niveau stimuleert multiperspectiviteit de inachtname van meerdere perspectieven in de analyse van historische fenomenen.[7] Dit kan via

– het simultaan analyseren van historische fenomenen in hun lokale, nationale, regionale en globale dimensie, waarbij de verschillende perspectieven worden verstrengeld;[8]

– de integratie van meerdere actoren, historische bronnen, narratieve plots en types historiografie;[9] en

– de toepassing van een interactie – en communicatiemodel in de analyse van interculturele contacten.[10]

Dit model focust op de wederzijdse invloed in de ontmoeting van culturen, en onderzoekt bronnen van de West-Europese “zelf” en “de ander”. De centrale vraag luidt hoe de “zelf” en “de ander” elkaar veranderden ten gevolge van de contacten. In dit model worden alle betrokkenen agency toegekend, en worden wederzijdse representaties onderzocht. Op die manier wordt een West-Europees georiënteerde eurocentrische blik doorbroken. Bovendien beschouwt dit model “wij” en “zij” als een dynamisch en veranderlijk gegeven, in zoverre zelfs dat “wij” en “zij” soms opgaan in een gezamenlijk nieuw “wij”. Dit model laat niet toe “wij” duidelijk te scheiden van “zij”, aangezien beide elkaar beïnvloedden en veranderden. Identiteit wordt dus niet langer beschouwd als een homogeen en onveranderlijk gegeven.

De voornoemde benaderingen tonen aan dat multiperspectiviteit simultaan kan leiden tot een beter begrip van het verleden onder leerlingen, het historisch denken van leerlingen kan bevorderen, en kan bijdragen tot een kritische en open identiteitsvorming onder leerlingen.

_____________________

Verder Lezen

- Saïd,Edward. Oriëntalisten. Antwerpen: Standaard, 2005.

- Stuurman, Siep. De uitvinding van de mensheid. Korte wereldgeschiedenis van het denken over gelijkheid en cultuurverschil. Amsterdam: Bert Bakker, 2010.

Web Resources

- Een voorbeeld van een interculturele aanpak vind je op deze website over ‘Slavenhandel in de Atlantische wereld’: http://atlanticslavetrade.eu/colofon (last accessed 11 February 2017).

- Project van het Centrum voor de Geschiedenis van Migranten: http://www.vijfeeuwenmigratie.nl/ (last accessed 11 February 2017)

_____________________

[1] Tessa Lobbes and Kaat Wils, “National History Education in Search of an Object. The Absence of History Wars in Belgian Schools”, in History Education under Fire. An International Handbook, ed. by Luigi Cajani, Simone Lässig and Maria Repoussi (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, the publiceren). Bert Vanhulle, “The path of history: narrative analysis of history textbooks – a case study of Belgian history textbooks (1945-2004),” History of Education 38, no. 2 (2009): 263-282. Karel Van Nieuwenhuyse and Kaat Wils, “Historical narratives and national identities. A Qualitative Study of Young Adults in Flanders,” Journal of Belgian History 45, no. 2 (2015): 40-72.

[2] Flemish Ministry of Education and Training, “Secundair onderwijs, derde graad ASO: uitgangspunten en vakgebonden eindtermen geschiedenis”, (Brussels, 2000), http://www.ond.vlaanderen.be/curriculum/secundair-onderwijs/derde-graad/ (last accessed 11 February 2017).

[3] Karel Van Nieuwenhuyse, “Increasing criticism and perspectivism: Belgian-Congolese (post)colonial history in Belgian secondary history education curricula and textbooks (1990-present),” International Journal of Research on History Didactics, History Education, and Historical Culture 36 (2015): 183-204.

[4] Van Nieuwenhuyse and Wils, “Historical narratives and national identities. A Qualitative Study of Young Adults in Flanders,” Journal of Belgian History 45, no. 2 (2015): 40-72.

[5] Terri Epstein, Interpreting National History. Race, Identity, and Pedagogy in Classrooms and Communities. (New York-London: Routledge, 2009). Kees Ribbens, “A narrative that encompasses our history: historical culture and history teaching,” in Beyond the canon. History for the twenty-first century, ed. Maria Grever and Siep Stuurman (Hampshire-New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2007), 63-78. Peter Seixas, “Historical understanding among adolescents in a multicultural setting,” Curriculum Inquiry 23, no. 3 (1993): 301-327.

[6] William McNeill, A World History (Oxford: University Press, 1998). Siep Stuurman, The Invention of Humanity. Equality and Cultural Difference in World History (Cambridge, MA – London: Harvard University Press, 2017).

[7] Robert Stradling, Multiperspectivity in History Teaching (Strasbourg: Council of Europe, 2003).

[8] Urte Kocka, “Rethinking the local and the national in a global perspective,” International Journal of Research on History Didactics, History Education, and Historical Culture 37 (2016): 109-118.

[9] Maria Grever, “De antropologische wending op microniveau. Cultureel pluralisme en gemeenschappelijke geschiedenis,” in Grenzeloze gelijkheid. Historisch vertogen over cultuurverschil, ed. Maria Grever, Ido De Haan, Dienke Hondius and Susan Legêne (Amsterdam: Bert Bakker, 2011): 272-288.

[10] Nicolas Standaert, Methodology in View of Contact between Cultures: The China Case in the 17th Century ( Hong Kong: Centre for the Study of Religion and Chinese society, 2002).

_____________________

Afbeelding Credits

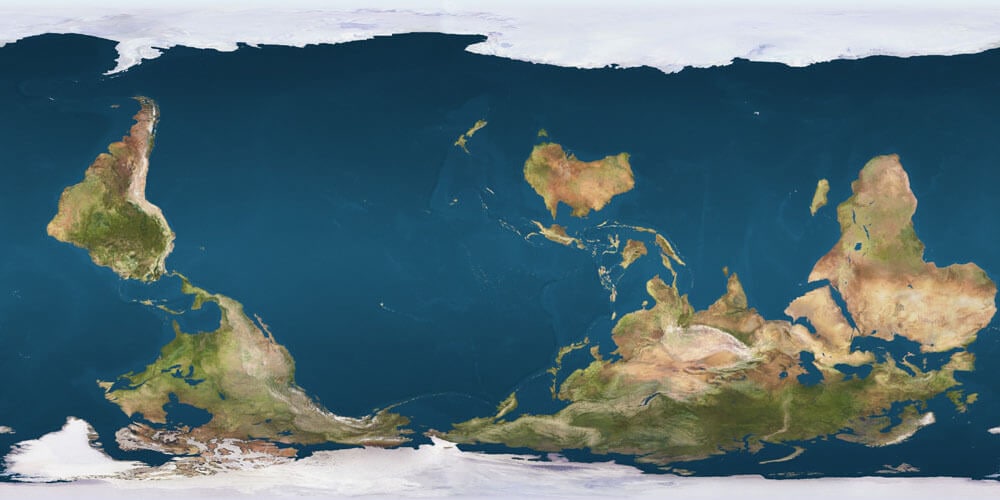

Reversed Earth Map © Poulpy, from a work by jimht at shaw dot ca, modified by Rodrigocd, 2008, public domain, commons wikimedia

Aanbevolen Citation

van Nieuwenhuyse, Karel: Using multiperspectivity to break through Eurocentrism. In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 9, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-8597

In a lesson on Belgian history, a teacher mentions: “And we have the most progressive constitution of Europe in 1831, meaning some countries did not have those rights yet. In Russia, serfdom still existed. Farmers were the property of the nobility.” A history textbook chapter on Japan under the Meiji (1867-1912) starts as follows: “19th century Japan was still characterized by feudalism.” Another textbook, dealing with the Ancien Régime, stresses that from the 14th century onwards, in Western Europe serfdom disappeared, while in Eastern Europe serfdom was by contrast reinforced.

A Eurocentric Approach of the Past

At the same time, the progressive religious toleration policy of Polish king Casimir in the same 14th century, confirming privileges and protections previously granted to Jews and encouraging them to settle in Poland (while exiled from England and France), remains ignored. Those outspoken examples clearly testify of a very Western-European oriented Eurocentric approach of the past. Eurocentrism in history education refers to two things: (1) a curriculum especially paying attention to European history, and (2) (Western) Europe serving as the standard to judge other societies upon.

The abovementioned examples neatly reflect the very Eurocentric orientation of the history curriculum in Flanders, the Dutch-speaking northern part of Belgium.[1] That curriculum seems to suggest that the most important part of world history is to be found in the historical trajectory of Europe (and the Western World), characterized by a slow but steady movement towards democracy and freedom. In that sense, it constitutes a new articulation of the old division, dating back to 19th century Belgian history education, between the West and “The Rest”.[2]

This Eurocentric approach has important implications, especially when taking into account the main goals for Flemish history education. On the one hand, the subject is expected to introduce students in the academic discipline of history. On the other hand, history education should prepare and raise “pupils as members of society”, meaning, among others, to support young people in their identity building process. The curriculum does not refer to, nor tries to support, a (sub)national identity. By contrast, it can be noticed that the main frame of reference is Western (European).[3]

Implications of Eurocentrism

What are those implications then? First, the Western European oriented Eurocentric approach of the past does not meet the expectation of introducing students in academic historiography, on two levels.

(1) It impedes students’ nuanced and broad understanding of the past. By only focusing on Western Europe and largely ignoring other parts of Europe and by extension of the world, such approach only offers a very limited, narrow-minded and one-sided representation of the past; furthermore, it gives the obviously wrong impression as if Western Europe always was in the center of human civilization and could hence serve as the standard to judge other societies upon.

(2) Besides, a Eurocentric account also hinders students’ ability to think historically. For important aspects of historical thinking are simply ignored in Eurocentric approaches. The inclusion of multiple perspectives for instance is absent, just as diverse historical sources from different actors, as well as any reflection on the agency of states, peoples, groups and individuals. Textbook accounts for instance simply do not mention the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth – at the time one of the largest and most populous states in Europe – in accounts on the early modern period. They also ignore the indigenous peoples in accounts on 19th century modern imperialism.[4]

The absence of non-Western European voices closely connects to a second important implication, for students’ identity-building. The Eurocentric suggestion that Western Europe always was in the center of human civilization, might give rise to feelings of superiority. Young people in Flanders, belonging to the white majority group, might get the idea that ‘their’ culture was and still is superior to any other culture. Such thinking can easily lead to an us-versus-them stance and to an exclusive and excluding social identity-building process. Previous research has revealed that this mechanism indeed occurs.[5] Young people from minority groups, on the other hand, risk to not feel at home in such history education that considers every non-Western European culture as backward, hence causing feelings of alienation towards current society.[6]

Multiperspectivity

The question then raises what can be done to go beyond a Western European oriented Eurocentric approach. The inclusion of multiperspectivity in history education might constitute a fertile strategy. This can be done both on a content and on a didactical level. On a content level, multiperspectivity encourages to include other perspectives and histories than solely Western European ones. This can be accomplished by focusing for instance on intercultural contacts – as important motors of change in the past [7] –, or on migration flows. Both approaches per se include more than only Western European societies. At the same time, they avoid the pitfall of a “world history” approach without any center, risking to make history insignificant for students, as they do not discern much connections with their position in the present.

On a didactical level, multiperspectivity encourages to view historical events from several perspectives.[8] This can be accomplished, for instance

– by looking at the same time at local, national, regional and global dimensions of any historical issue, and entangling those perspectives;[9]

– by including multiple actors, historical sources, narrative plots and types of historiography;[10] and

– by applying an interaction- and communication framework when addressing intercultural contacts.[11]

This framework focuses on the reciprocal influences in an encounter, and examines sources of the Western European “self” and “the other”. The central question is how the “self” and “the other” changed each other as a result of the contacts. In this framework, both parties are attributed agency, and also reciprocal representations are examined. It hence breaks through a Western European oriented Eurocentric view. Furthermore, the framework considers “us” and “them” as dynamic and changeable issues, in so far that “us” and “them” may sometimes transform into a new “us”. It does not allow to make a clear-cut distinction between the “us” and “them” since both influence and change each other. Identity is considered as a dynamic, and not a homogeneous and fixed issue anymore.

The abovementioned approaches hence show that multiperspectivity can at the same time lead to enriching young people’s understanding of the past, to fostering their understanding of history and their ability to think historically, and to contributing to a critical and open-minded identity-building process among young people.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Saïd, Edward. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books, 1979.

- Stuurman, Siep. The Invention of Humanity. Equality and Cultural Difference in World History. Cambridge, MA – London: Harvard University Press, 2017.

Web Resources

- Website of the Association of European Migration Institutions: http://aemi.eu/ (last accessed 11 February 2017).

- An example of an intercultural approach is to be found on a website on “Slave trade in the Atlantic world”: http://atlanticslavetrade.eu/colofon (last accessed 11 February 2017).

_____________________

[1] Flanders is mentioned here, not Belgium, because in 1989, the power in matters of education in Belgium was formally transferred from the national, federal level to the three Belgian “communities”, the Dutch (Flemish), French, and (very small) German communities. “Belgian” history education then ceased to exist.

[2] Tessa Lobbes and Kaat Wils, “National History Education in Search of an Object. The Absence of History Wars in Belgian Schools,” in History Education under Fire. An International Handbook, ed. by Luigi Cajani, Simone Lässig and Maria Repoussi (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, forthcoming). Bert Vanhulle, “The path of history: narrative analysis of history textbooks – a case study of Belgian history textbooks (1945-2004),” History of Education 38, no. 2 (2009): 263-282. Karel Van Nieuwenhuyse and Kaat Wils, “Historical narratives and national identities. A Qualitative Study of Young Adults in Flanders,” Journal of Belgian History 45, no. 2 (2015): 40-72.

[3] Flemish Ministry of Education and Training, “Secundair onderwijs, derde graad ASO: uitgangspunten en vakgebonden eindtermen geschiedenis” (Brussels, 2000), http://www.ond.vlaanderen.be/curriculum/secundair-onderwijs/derde-graad/ (last accessed 11 February 2017).

[4] Karel Van Nieuwenhuyse, “Increasing criticism and perspectivism: Belgian-Congolese (post)colonial history in Belgian secondary history education curricula and textbooks (1990-present),” International Journal of Research on History Didactics, History Education, and Historical Culture 36 (2015): 183-204.

[5] Van Nieuwenhuyse and Wils, “Historical narratives and national identities. A Qualitative Study of Young Adults in Flanders,” Journal of Belgian History 45, no. 2 (2015): 40-72.

[6] Terri Epstein, Interpreting National History. Race, Identity, and Pedagogy in Classrooms and Communities. (New York-London: Routledge, 2009). Kees Ribbens, “A narrative that encompasses our history: historical culture and history teaching,” in Beyond the canon. History for the twenty-first century, ed. Maria Grever and Siep Stuurman (Hampshire-New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2007), 63-78. Peter Seixas, “Historical understanding among adolescents in a multicultural setting,” Curriculum Inquiry 23, no. 3 (1993): 301-327.

[7] William McNeill, A World History (Oxford: University Press, 1998). Siep Stuurman, The Invention of Humanity. Equality and Cultural Difference in World History (Cambridge, MA – London: Harvard University Press, 2017).

[8] Robert Stradling, Multiperspectivity in History Teaching (Strasbourg: Council of Europe, 2003).

[9] Urte Kocka, “Rethinking the local and the national in a global perspective,” International Journal of Research on History Didactics, History Education, and Historical Culture 37 (2016): 109-118.

[10] Maria Grever, “De antropologische wending op microniveau. Cultureel pluralisme en gemeenschappelijke geschiedenis,” in Grenzeloze gelijkheid. Historisch vertogen over cultuurverschil, ed. Maria Grever, Ido De Haan, Dienke Hondius and Susan Legêne (Amsterdam: Bert Bakker, 2011): 272-288.

[11] Nicolas Standaert, Methodology in View of Contact between Cultures: The China Case in the 17th Century ( Hong Kong: Centre for the Study of Religion and Chinese society, 2002).

_____________________

Image Credits

Reversed Earth Map © Poulpy, from a work by jimht at shaw dot ca, modified by Rodrigocd, 2008, public domain, commons wikimedia

Recommended Citation

van Nieuwenhuyse, Karel: Using multiperspectivity to break through Eurocentrism. In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 9, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-8597

In einer Lektion über die Geschichte Belgiens erwähnt eine Lehrperson Folgendes: “Und im Jahre 1831 hatten wir die fortschrittlichste Verfassung von Europa, was bedeutet, dass einige Länder diese Rechte noch nicht besaßen. In Russland gab es immer noch die Leibeigenschaft. Bauern waren Besitz des Adels.” Ein Kapitel eines Schulgeschichtsbuchs über Japan unter der Herrschaft von Meiji (1867-1912) beginnt wie folgt: “Japan im 19. Jahrhundert war immer noch charakterisiert durch den Feudalismus.” Ein anderes Schulgeschichtsbuch, welches sich mit dem Ancien Régime befasst, betont, dass die Leibeigenschaft in Westeuropa vom 14. Jahrhundert an langsam zurückging, während sie im Gegensatz dazu in Osteuropa zunahm.

Eine eurozentrische Sichtweise

Gleichzeitig bleibt die fortschrittliche Politik der religiösen Toleranz des polnischen Königs Kasimir in eben diesem 14. Jahrhundert, die die den Juden zuvor gewährten Privilegien und Schutzzusicherungen bestätigte und sie dazu ermutigte, sich in Polen niederzulassen (wohingegen diese aus England und Frankreich verbannt wurden), unbeachtet. Diese aussagekräftigen Beispiele belegen ganz klar eine auf Westeuropa ausgerichtete eurozentrische Sichtweise der Vergangenheit. Eurozentrismus im Geschichtsunterricht verweist auf zweierlei Dinge: (1) Einen Lehrplan, der speziell auf (west)europäische Geschichte fokussiert, und (2) ein (West-)Europa, das zum Standard für die Beurteilung anderer Gesellschaften gemacht wird.

Die oben erwähnten Beispiele spiegeln die eurozentrische Ausrichtung des Geschichtslehrplans in Flandern, dem niederländisch-sprachigen nördlichen Teil Belgiens, wider.[1] Dieser Lehrplan scheint zu suggerieren, dass die wichtigsten Aspekte der Weltgeschichte in der geschichtlichen Entwicklung Europas und der westlichen Welt zu finden sind, die sich vor allem durch eine langsame, aber stetige Bewegung hin zu Demokratie und Freiheit auszeichnet. In diesem Sinne stellt er eine neue Ausprägung des seit dem 19. Jahrhunderts im belgischen Geschichtsunterricht gebräuchlichen Erzählmusters einer alten Teilung der Welt in “den Westen” und “den Rest” dar.[2]

Die eurozentrische Ausrichtung hat erhebliche Auswirkungen, vor allem, wenn man die Hauptziele des flämischen Geschichtsunterrichts in Betracht zieht. Einerseits wird vom Fach erwartet, dass es die Lernenden in die akademische Disziplin der Geschichte einführt. Andererseits soll der Geschichtsunterricht die SchülerInnen auf ihre Rolle als “Mitglieder der Gesellschaft” vorbereiten und in ihrem Prozess der Identitätsbildung unterstützen. Der Lehrplan bezieht sich dabei aber weder auf eine (sub)nationale Identität, noch versucht er eine solche zu fördern. Es kann im Gegenteil festgestellt werden, dass der Westen den Hauptbezugsrahmen bildet.[3]

Auswirkungen des Eurozentrismus

Welches sind dann die Auswirkungen eines solchen Geschichtsunterrichts? Auf zwei Ebenen erfüllt die westeuropäisch ausgerichtete eurozentrische Sichtweise auf die Vergangenheit nicht die Erwartungen an eine Einführung der SchülerInnen in die akademische Historiographie:

(1) Sie erschwert das nuancierte und breite Verständnis der Vergangenheit von SchülerInnen. Indem sie nur auf Westeuropa fokussiert und andere Teile von Europa und – in einer weiteren Ausdehnung – der Welt ignoriert, bietet solch eine Sichtweise nur eine sehr limitierte, enggeführte und einseitige Darstellung der Vergangenheit. Darüber hinaus vermittelt sie den offensichtlich falschen Eindruck, als ob Westeuropa immer das Zentrum der menschlichen Zivilisation gebildet hätte und daher als Standard dienen könne, um andere Gesellschaften zu beurteilen.

(2) Ausserdem beeinträchtigt ein eurozentrischer Zugriff auf die Vergangenheit die SchülerInnen in ihrem Vermögen historisch zu denken. Denn wichtige Aspekte des historischen Denkens werden durch die eurozentrische Perspektive ignoriert. Die Berücksichtigung vielfältiger Perspektiven fehlt zum Beispiel ebenso, wie das Berücksichtigen unterschiedlicher Quellen von verschiedenen Akteuren und das Reflektieren über die Handlungsmöglichkeiten von Staaten, Völkern, Gruppen und Einzelpersonen. Die Schulgeschichtsbücher erwähnen zum Beispiel in Darstellungen über die frühe Neuzeit schlicht nicht die polnisch-litauische Union – zu dieser Zeit einer der grössten und bevölkerungsreichsten Staaten in Europa – und sie übergehen auch die indigenen Bevölkerungsgruppen in den Darstellungen über den modernen Imperialismus des 19. Jahrhunderts.[4]

Das Fehlen von nicht-westeuropäischen Stimmen steht in engem Bezug zu einer zweiten wesentlichen Auswirkung, nämlich die der Identitätsbildung von SchülerInnen. Das eurozentrisch ausgerichtete Suggerieren, dass Westeuropa immer das Zentrum der menschlichen Zivilisation darstellte, könnte möglicherweise Gefühle der Überlegenheit hervorrufen. Jugendliche in Flandern, die der weißen Mehrheitsgruppe angehören, könnten auf die Idee kommen, dass “ihre” Kultur irgendeiner anderen Kultur überlegen gewesen sei und dies immer noch wäre. Solch ein Denken kann leicht zu einer “Wir-gegen-Andere-Haltung” und zu einem exklusiven und ausschließenden sozialen Identitätsbildungsprozess führen. Die bisherige Forschung hat aufgezeigt, dass dieser Mechanismus in der Tat stattfindet.[5] Jugendliche aus Minderheitsgruppen sind andererseits der Gefahr ausgesetzt, sich in solch einem Geschichtsunterricht, der jede nicht-europäische Kultur als rückständig betrachtet, nicht heimisch zu fühlen. Daher mag diese Form des Unterrichts auch Gefühle der Entfremdung gegenüber der heutigen Gesellschaft verursachen.[6]

Multiperspektivität

Es stellt sich so die Frage, was getan werden kann, um die westeuropäisch ausgerichtete eurozentrische Sichtweise zu überwinden. Das Einbeziehen von Multiperspektivität in den Geschichtsunterricht könnte eine ergiebige Strategie darstellen. Das kann sowohl auf einer inhaltlichen als auch auf einer didaktischen Ebene stattfinden. Auf der inhaltlichen Ebene motiviert Multiperspektivität dazu, andere Perspektiven und Darstellungen als nur die westeuropäischen zu integrieren. Dies kann erreicht werden, indem zum Beispiel auf interkulturelle Kontakte oder auf Migrationsbewegungen als wichtige Motoren des Wandels in der Vergangenheit fokussiert wird.[7] Beide Sichtweisen schliessen per se mehr als nur westeuropäische Gesellschaften ein. Gleichzeitig vermeidet die Einbeziehung von Perspektivwechseln die Falle einer “Weltgeschichte” ohne Zentrum. Letztere birgt das Risiko, dass diese Form der “Weltgeschichte” für SchülerInnen aufgrund der Tatsache, dass nur wenige Bezüge zu ihrer eigenen gegenwärtigen Lebenswelt hergestellt werden, als etwas Irrelevantes erscheint.

Auf der didaktischen Ebene motiviert Multiperspektivität dazu, historische Ereignisse von verschiedenen Perspektiven aus zu betrachten.[8] Dies kann zum Beispiel erreicht werden, indem

– gleichzeitig lokale, nationale, regionale und globale Dimensionen eines historischen Themas in Betracht gezogen werden und diese Perspektiven analytisch und narrativ verknüpft werden;[9]

– indem zahlreiche Akteure, historische Quellen, narrative Plots und Arten von Historiographie miteinbezogen werden;[10] und

– indem ein Interaktions- und Kommunikationsrahmen bei der Thematisierung interkulturelle Kontakte angewendet wird.[11]

Dieser Rahmen fokussiert auf die wechselseitigen Einflüsse einer Begegnung und prüft Quellen des westeuropäischen “Selbst” und “des Anderen”. Die zentrale Frage stellt sich darin, auf welche Weise das “Selbst” und “das Andere” einander als Ergebnis des Kontakts beeinflussen. In diesem Rahmen wird beiden Parteien Handlungsautorität zugesprochen und die wechselseitigen Darstellungen werden ebenso untersucht. Somit kann eine westeuropäisch ausgerichtete eurozentrische Sicht überwunden werden. Im Weiteren betrachtet dieser Rahmen das “Uns” und das “Sie” als dynamische und veränderbare Entitäten, insoweit, als dass das “Uns” und das “Sie” sich manchmal in ein neues “Uns” transformieren. Er erlaubt, eine eindeutige Unterscheidung zwischen dem “Uns” und dem “Sie” zu vermeiden, weil sich beide gegenseitig beeinflussen und verändern. Identität wird als eine dynamische und nicht mehr als eine homogene und fixierte Entität betrachtet.

Die oben erwähnten Sichtweisen zeigen daher auf, dass Multiperspektivität gleichzeitig dazu führen kann, dass das Verständnis der Jugendlichen für die Vergangenheit gesteigert, dass deren Geschichtsverständnis und deren Fähigkeit zum historischen Denken gefördert und dass ein Beitrag geleistet wird zu einem kritischen und von Offenheit geprägten Identitätsbildungsprozess.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Edward Saïd: Orientalism. New York 1979.

- Siep Stuurmann: The Invention of Humanity. Equality and Cultural Difference in World History. Cambridge u.a. 2017.

Webressourcen

- Website der Association of European Migration Institutions: http://aemi.eu/ (letzter Zugriff 11.2.2017).

- Die Website “Slave trade in the Atlantic world” ist ein Beispiel für einen interkulturellen Ansatz: http://atlanticslavetrade.eu/colofon (letzter Zugriff 11.2.2017).

_____________________

[1] Flandern und nicht Belgien wird hier erwähnt, weil in Belgien die Kompetenz in Bildungsangelegenheiten im Jahr 1989 formell von der nationalen, bundesstaatlichen Ebene zu den drei belgischen “Kommunen”, der niederländischen (flämischen), französischen und (sehr kleinen) deutschen Kommune transferiert wurde. Ein “belgischer” Geschichtsunterricht besteht seither nicht mehr.

[2] Tessa Lobbes/Kaat Wils: National History Education in Search of an Object. The Absence of History Wars in Belgian Schools. In: Luigi Cajani/Simone Lässig/Maria Repoussi (Hrsg.): History Education under Fire. An International Handbook. Göttingen (in Kürze erscheinend). Bert Vanhulle: The path of history: narrative analysis of history textbooks – a case study of Belgian history textbooks (1945-2004). In: History of Education 38 (2009), H. 2, S. 263-282. Karel Van Nieuwenhuyse/Kaat Wils: Historical narratives and national identities. A Qualitative Study of Young Adults in Flanders. In: Journal of Belgian History 45 (2015), H.2, S. 40-72.

[3] Flemish Ministry of Education and Training: Secundair onderwijs, derde graad ASO: uitgangspunten en vakgebonden eindtermen geschiedenis. Brüssel 2000, http://www.ond.vlaanderen.be/curriculum/secundair-onderwijs/derde-graad/ (letter Zugriff 11. Februar 2017).

[4] Karel Van Nieuwenhuysen: Increasing criticism and perspectivism: Belgian-Congolese (post)colonial history in Belgian secondary history education curricula and textbooks (1990-present). In: International Journal of Research on History Didactics, History Education, and Historical Culture 36 (2015), S. 183-204.

[5] Van Nieuwenhuyse/Wils (Anm. 2).

[6] Terri Epstein: Interpreting National History. Race, Identity, and Pedagogy in Classrooms and Communities. New York/London 2009. Kees Ribbons: A narrative that encompasses our history: historical culture and history teaching. In: Maria Grever/Siep Stuurman (Hrsg.): Beyond the canon. History for the twenty-first century. Hampshire/New York 2007, S. 63-78. Peter Seixas: Historical understanding among adolescents in a multicultural setting. In: Curriculum Inquiry 23 (1993), H. 3, S. 301-327.

[7] William McNeill: A World History. Oxford 1998. Step Stuurman: The Invention of Humanity. Equality and Cultural Difference in World History. Cambridge u.a. 2017.

[8] Robert Stradling: Multiperspectivity in History Teaching. Strasbourg 2003.

[9] Urte Kocka: Rethinking the local and the national in a global perspective. In: International Journal of Research on History Didactics, History Education, and Historical Culture 37 (2016), S. 109-118.

[10] Maria Grever: De antropologische wending op microniveau. Cultureel pluralisme en gemeenschappelijke geschiedenis. In: Maria Grever u.a. (Hrsg.): Grenzeloze gelijkheid. Historisch vertogen over cultuurverschil. Amsterdam 2011, S. 272-288.

[11] Nicolas Standaert: Methodology in View of Contact between Cultures: The China Case in the 17th Century. Hong Kong, 2002.

_____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

Reversed Earth Map © Poulpy, from a work by jimht at shaw dot ca, modified by Rodrigocd, 2008, public domain, commons wikimedia

Übersetzung

Kurt Brügger swiss american language expert

Empfohlene Zitierweise

van Nieuwenhuyse, Karel: Eurozentrismus gegen Mulitperspektivität. In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 9, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-8597

Copyright (c) 2017 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 5 (2017) 9

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-8597

Tags: Belgium (Belgien), Eurocentrism (Eurozentrismus), Language: Dutch, Multiperspectivity (Multiperspektivität), Textbook (Schulbuch)

Thank you, Karel, for mentioning Poland and its historical achievements.

Interestingly, in Poland the school narrative is no less Eurocentric than in Flanders, only Poland is added. Other East-European countries appear only as a background for the events in Poland or in the Western Europe, and–just as in Belgium–serve as points of reference for the [Western] European civilization. It could be explained by the fact that the Polish people have always regarded themselves as part of the Western civilization and despite various historical obstacles tried to keep in touch with the Western science, literature–and historiography, and thus acquired also its Eurocentrism. Both historians and politicians complain from time to time that Poland is largely missing from the European (and world) historical narratives, but at the same time pay little attention to other than Polish and (Western) European perspectives.

I am not sure, however, if the “world history” necessarily makes history teaching insignificant to students. As Anna Clark noticed, Australian students are fascinated with the American history while bored by the Australian one so perhaps you do not have to use school history to help students make “connections with their position in the present” in order to make it attractive and significant for them.[1] Which does not mean that I am against the idea of multiperspectivity in history education, but other options need not be rejected out of hand.

References

[1] Anna Clark, History’s Children: History Wars in the Classroom (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2008).

This is an enlightening and thought-provoking contribution to the generally understudied area of world history curricula and their potential influences on students’ worldviews and attitudes. My reflections generally attempt to help us pay due attention to some nuances that could allow for effectively introducing multiperspectivity to world history curricula. I would propose that such understandings are important if we are to successfully confront exclusivist narratives and “us-versus-them” attitudes that white majority – as well as minority students – might bring into the classroom.

First, Van Nieuwenhuyse offers an extremely helpful distinction of what he calls a “Western European oriented Eurocentric approach” inviting us to further deconstruct and interrogate nuances embedded within conceptions of Eurocentrism. Such an approach to “Eurocentrism” – often simplistically handled as a monolithic, catchall term – allows us to thoughtfully analyze it, thus finding means to potentially counter its dominance in curricula and classrooms. Parallel to such deconstruction, as scholars and educators interested in history education globally, it would be important that we recognize Eurocentrism as one manifestation among other forms of exclusivist or mono-perspectival approaches employed to teach history in or outside of schools in numerous contexts.

Globally, world history is largely dominated by ethnocentrism, where the dominant group perspective serves as the prism through which world history is narrated. This ethnocentrism might manifest itself as Eurocentrism in Western contexts – such as in the Netherlands (Weiner, 2014), the United States (Marino, 2011; VanSledright, 2008), and New Zealand (Sheehan, 2010) – or as other ethnocentric and self-aggrandizing approaches to world history in numerous non-Western contexts. Understanding Eurocentrism as part of a larger global reality carries the promise of offering new insights into the question of minority students, especially those hailing from non-Western backgrounds, and how they interact with history education in Western contexts. Many of those minority students, including immigrants and recent immigrants, would have to negotiate at least two competing historical narratives: a dominant Eurocentric historical narrative, and another potentially equally exclusivist, ethnocentric narrative sustained by their own communities.

These exclusivist and ethnocentric approaches are closely intertwined and feed into the “us-versus-them” stance which students bring into the classroom, as Van Nieuwenhuyse posits. In that context, we tend to focus on understanding minority students’ sense of alienation from history education – and society at large – as a reaction to the exclusion of their communities’ historical narratives and contributions from the dominant narrative. But it might be instructive to widen our scope by examining and investigating other historical narratives these students are exposed to. That would entail analyzing historical narratives and worldviews propagated by families, religious institutions, and other community groups that minority students might be influenced by. These historical narratives – oftentimes mirroring forms of supremacist or exclusivist narratives – potentially gain additional traction because they offer these minority students a sense of pride and belonging that they lack elsewhere in society.

That being said about minority students, it is as important to be cognizant of how such “us-versus-them” stance influences intergroup dynamics among dominant cultural and linguistic groups in contexts where those co-exist, such as in Belgium with its sizeable Dutch and French-speaking communities. The context of Quebec offers helpful insights into how this specific “us-versus-them” stance influences students’ understanding of the past, and how it might shape attitudes and interactions between cultural and linguistic groups such as French-speaking and English-speaking communities in Quebec (e.g., Lévesque, Létourneau, & Gani, 2012). In other words, such a sense of dichotomy or superiority that this approach nourishes is not only potentially problematic for how white students view and interact with non-whites, but becomes a template that informs their interaction with other whites who are culturally or linguistically different, such as Flemish vis-à-vis French-speaking Belgians, or Belgians and Western Europeans vis-à-vis Eastern Europeans.

Finally, Van Nieuwenhuyse rightly warns that such a Eurocentric approach that ignores exposing students to multiple perspectives in world history impedes the development of their historical thinking. I would add that such an approach precludes students’ development of other important historical thinking dimensions as well, such as “continuity and change,” or “cause and consequence” which could be fostered by exposing students to the reciprocal influences that resulted through Western civilizations’ intercultural contacts and exchanges with geographically proximate civilizations, such as those of Eastern Europe, or more distant ones in Asia, Africa, and elsewhere.

References

– Stéphane Lévesque, Jocelyn Létourneau and Gani Raphaël, “Québec Students’ Historical Consciousness of the Nation”, Canadian Issues/Thèmes Canadiens, Spring (2012), 55–60.

– Michael P. Marino, “High School World History Textbooks: An Analysis of Content Focus and Chronological Approaches,” The History Teacher, 44 (2011), 421–446.

– Mark Sheehan, “The Place of ‘New Zealand’ in the New Zealand History Curriculum,” Journal of Curriculum Studies, 42(5) (2010), 671-691. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2010.485247

– Bruce VanSledright, “Narratives of Nation-State, Historical Knowledge and School History Education,” Review of Research in Education, 32(1) (2008), 109–146.

– Melissa F. Weiner (2014), “(E)Racing Slavery,” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 11(02), 329-351.

In this contribution, Karel Van Nieuwenhuyse provides a convincing analysis of the problem of Eurocentrism in European history education. I agree with his diagnosis and share his views on how to tackle it. However, I would argue that for breaking through Eurocentrism in history education, ‘multiperspectivity’ will not be enough. It is the focus on situations of ‘interdependence’ and ‘entanglement’ that holds the most promising answers to the problem.

My comment is based on the question of how ‘Non-European’ and especially ‘African’ history is currently taught in Switzerland. In contrast to what Nieuwenhuyse states for the case of Flanders, Swiss history curriculums do not categorically ignore “other parts of Europe and by extension of the world” by focusing solely on Western Europe. Although curriculums vary from canton to canton and from school to school, many devote considerable parts of the syllabus to the study of African, Latin American, Russian, or Asian history. An interest in ‘Non-Western-European’ history is also reflected in Swiss history text books. The book Weltgeschichte, for instance, contains some highly-nuanced sections on different regions of the world, including one on ‘Africa’ that starts by discussing persisting conceptions of the continent’s history.[1] A second Swiss text book, the Schweizer Geschichtsbuch, includes significant chapters on the history of China, South Eastern Europe and the Middle East.[2] Interestingly, there is no separate chapter on the history of Africa. Instead, aspects of the continent’s past are included in sections on the history of imperialism and decolonisation. There, the book makes good use of the concept of ‘multiperspectivity’. Students are invited, for instance, to compare two speeches that were given in Léopoldville on 30 June 1960, the day of Congolese independence: one by King Baudouin of Belgium and the other by Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba. These two sources represent two very different interpretations of Congolese, Belgian and colonial history and therefore allow for a complex analysis of the topic.[3]

So Eurocentrism is not a problem in Swiss history education? On the contrary. Troubling, for example, is an explanation given on the first pages of the book Weltgeschichte. It justifies the book’s focus on world history “from 1500 to the present” by stating that the years around 1500 mark the beginning of a European “Sonderweg” in history.[4] Europe’s extraordinariness and the continent’s dominance over ‘other parts of the world’ are thus presented as given characteristics of history, which are subsequently explained and substantiated in the book. There is a second, more fundamental problem: As the examples above indicate, a basic distinction between Swiss, European and Non-European histories persists in curriculums and text books. Whenever the boundaries between these categories are lifted, it happens with a unilateral focus on European control and dominance over another part of the world.

In recent years, various scholars have drawn attention to the diverse ways in which Swiss institutions and personalities were part of the colonial and postcolonial world order. Swiss researchers, aid workers, missionaries and entrepreneurs lived and worked in Africa, Latin America, the Middle East and Asia. They did so in a variety of positions of power or dependence, participating in colonial structures and, in rare cases, also contributed in bringing them down. On the other hand, people in Switzerland were highly influenced by encounters with individuals and thoughts from other parts of the world.[5] Such multi-layered encounters – or “intercultural contacts” as Nieuwenhuyse calls them – influenced (self-)perceptions and imaginations that are still powerful today. History lessons should thus not only teach the political history of imperial rule and decline, but also relate to the conflicting experiences of Swiss missionaries in the Gold Coast, the architecture of advertisements for colonial products in Europe, as well as on the long-term consequences of racist children’s books. This is not simply a way to add new perspectives to history, but one that can contribute to breaking down the divisions between what is considered to be ‘Swiss’ and ‘foreign’ or ‘European‘ and ‘African’ history in the first place. In short, so-called ‘Swiss history’ would then be a normal part of lessons on ‘African history’ and vice versa.

There is, finally, an additional possibility to handle the problem of Eurocentrism in history education: it can be addressed head-on. From personal experience, students are very open to reflect on the consequences of Eurocentric perspectives in history and everyday life. Drawing from their own experiences, they know the world to be far more complex than the clear-cut divisions between ‘Swiss’ and ‘Non-European’ history suggest. Thus, class discussions on the issue might teach us that younger generations are much more able and willing to change long-existing patterns of (self-)perception than the ones before them.

References

[1] Weltgeschichte. Von 1500 bis zur Gegenwart, Zürich 2014, pp. 368-384.

[2] Schweizer Geschichtsbuch 4. Zeitgeschichte seit 1945, Berlin 2014, pp. 184-323.

[3] Ibid., pp. 136-7.

[4] Weltgeschichte, p. 22.

[5] See among others Lukas Meier, Swiss Science, African Decolonization and the Rise of Global Health, 1940-2010, Basel 2014; Patricia Purtschert, Harald Fischer-Tiné (Ed.), Colonial Switzerland. Rethinking Colonialism from the Margins, Basingstoke 2015; Bernhard Schär, Tropenliebe. Schweizer Naturforscher und niederländischer Imperialismus in Südostasien um 1900, Frankfurt/M 2014; Lukas Zürcher, Die Schweiz in Ruanda. Mission, Entwicklungshilfe und nationale Selbstbestätigung (1900-1975), Zürich 2014.

Author’s Reply

Multiperspectivist teaching about intercultural contacts in the history classroom practice:

a slippery, yet meaningful and necessary path

Academic scholars can have great (or for that matter: also bad) ideas about how history should be taught in schools, but in the end, history teachers are the ones having to give shape to secondary school history education in daily classroom practice. Scholars therefore should always include, in their thinking, a reflection on the practical feasibility of what they suggest. The comments raised with regard to my initial contribution are hence all the more interesting, as they all partly relate to concrete classroom practice. I will especially further examine that matter, with regard to the challenges of a multiperspectivist history teaching of intercultural contacts.

Along with Patricia Hongler, I agree that multiperspectivity as a concept should be further operationalized. This can be done in terms of so-called societal domains (culture, politics, economy, religion etc.) as I referred indirectly to when writing about including “types of historiography”, corroborating sources, examining different perspectives within one group instead of homogenizing it, and indeed also to reciprocity, interdependency and entanglement, which is inherently part of the interaction- and communication framework, that I mentioned in my initial contribution.

I very much like the idea of Ehaab D. Abdou on connecting the notion of Eurocentrism to ethnocentrism in general, present in so many societies and communities all over the world, and in this respect, to connect formal with non-formal education (a necessary strategy Peter Seixas already in 1993 advocated for).[1] It would be of great interest to examine how different cultures perceive both themselves and “the other”. History teachers and their students could do that, for instance, through comparing excerpts of textbooks from different parts of the world. They could also corroborate school history with family stories, or with movies and oral testimonies circulating on YouTube, in order to connect to young people’s living environment and typical sources of information. A suggestion in this respect, in line with what Joanna Wojdon pertinently raised: why not ask the students themselves what interests them, and which materials they deem worthy to analyze in the history classroom?

This could be used as a starting point to deconstruct both Eurocentrism and ethnocentrism in general (probably also expressing itself through students’ interests) when teaching about intercultural contacts in the past, and to further understand how the phenomenon of ethnocentrism works and affects people’s (lack of) historical-critical thinking, people’s identity-building, and people’s civic attitudes towards “the other”. It might also shed light on how history (education) is (mis)used in intergroup conflicts.[2]

Two dangers, however, occur. The first relates to practical feasibility. It is very difficult and time-consuming for teachers to build an understanding of other societies, before being able to properly teach about them. This requires a great deal of effort, yet at the same time it is a necessary effort. Because if one does not build an in-depth understanding of “the other”, one risks to end up, in most cases, being the in-group majority (wo)man (teacher) telling other in-group majority people (students) how “the other” thinks and behaves.[3] And that is not supposed to be the purpose of course. Academia and academic scholars might be of great support for history teachers in this respect, by providing them with accessible information about (and sources of) other cultures. It clearly cannot be expected from history teachers to make the effort all by themselves.

Secondly, in deconstructing both Eurocentrism and ethnocentrism in general, history teachers should be aware of not reinforcing a relativist stance among students, and not making it seem as if, since societies all over the world behave ethnocentric, the ethnocentric approach is a kind of standard and the only possible one behavior. At the same time, it might also well be that through intercultural teaching, the awareness of an in-group sense of belonging, especially among young people from majority groups, increases, and that students hence will be drawing sharper lines between “us” and “them”.[4] Teaching about ethnocentrism runs the actual risk of reinforcing ethnocentric attitudes. Here, the connection between past, present and future immediately comes to the fore.

It is therefore not sufficient to solely deconstruct Eurocentrism or ethnocentrism in general, and to raise an intercultural historical consciousness among young people. Those should always go hand in hand with fostering students’ intercultural historical-critical thinking skills, in order to engage them in a shared, critical-reflective process about constructing alternative, historiographically grounded historical representations on intercultural contacts, on how various cultures were interdependent and entangled, and on how one could perceive and deal with intercultural contacts in the present.

In so doing, the interaction- and communication framework comes in very handy and useful. For it helps to build an understanding, based on solid historiographical knowledge and various historical sources, of how all parties involved in intercultural contacts throughout the past were influenced by the encounter, of how they represented each other, and also of how they experienced the contacts. As the latter notion of experiencing connects very well to historical empathy, the framework hence provides the opportunity to foster both students’ historical perspective taking, and also to bring into the history classroom the notion of caring.[5] It seems important, as young people are not only cognitive yet at the same time affective human beings, to also explicitly address (and deal with) emotions and affection in the history classroom, especially in response to the earlier mentioned risk of reinforcing us-versus-them feelings. This is all the more important while connecting the past to the present, and while critically reflecting on intercultural contacts in present-day society. Such a strategy might help in building a meaningful, communicative and dialogical, yet critical connection between past, present and future among young people, in preparing them for taking up their role in the multicultural societies of the 21st century. I purposely use the word “might”, because research still should empirically show – in general – this connection between historical thinking and civic attitude assumptions.

References

[1] Peter Seixas, “Historical understanding among adolescents in a multicultural setting,” Curriculum Inquiry 23, no. 3 (1993): 301-327.

[2] For that matter, see Recommendations for the History Teaching of Intergroup Conflicts. Brussels, 2017.

[3] I gratefully refer here to recent, most interesting conversations with Canadian colleagues Carla Peck, Paul Zanazanian, Raphael Gani, Ehaab D. Abdou and Nathalie Popa.

[4] Karel Van Nieuwenhuyse and Ellen Claes, “The impact of historical thinking on civic attitudes. Flemish case study migration history” (presentation at the EARLI conference in Tampere, Finland – Education in the crossroads of economy and politics – Role of research in the advancement of public good, 1 September 2017).

[5] Keith Barton and Linda Levstik, Teaching for the common good (Mahwah, NJ: Larence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, 2004).