Abstract: History educators frequently — and, I think, rightly — insist on the power and, even, the critical importance of knowing history and of thinking historically about our collective pasts. Should we, then, expect history education to display a heightened awareness of its own past and, if yes, what kind of relationship to this past should we expect history education to construct?

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10381.

Languages: English, Deutsch

History educators frequently — and, I think, rightly — insist on the power and, even, the critical importance of knowing history and of thinking historically about our collective pasts. Should we, then, expect history education to display a heightened awareness of its own past and, if yes, what kind of relationship to this past should we expect history education to construct?

Relationships to the Past

As theorists of historical consciousness have pointed out, there are many modes of relationship to the past. Crudely, we can distinguish between approaches to the past that are concerned with memory and identification, and approaches that not only treat the past as strange rather than familiar but that are also more concerned with building new and methodologically robust claims about the past than with present-affirming doxa.[1] The distinction is a crude one because “there is no such thing as ‘pure history,’ a science devoid of the characteristics of collective memory”.[2] Nevertheless, it remains analytically useful to separate dimensions of difference in our various modes of relationship to the past, including aesthetic, ethical, and material aspects. Doing so increases self-awareness of the plurality of our past-referencing practices, their purposes, and their various affordances and constraints.[3]

The distinction between history and memory is frequently used in discussions of school history to distinguish between contrasting approaches to curriculum. The distinction can also be used, I want to suggest, to increase reflexivity and criticality amongst history educators when they think about the history of their subject. I will make this case by discussing two dominant practical-historical narratives about history education in England, and by presenting an example to show how disciplinary-historical engagement with the past can destabilise such narratives and point to their limitations.

Declinist and Triumphalist Narrative Templates

Debates about history in education in England are frequently polarised and disfigured by ‘dialysis’ — the rhetorical trope that feeds off, and that seeks to create and deepen, ‘either/or’ and ‘us/them’ dichotomies.[4] The histories of school history deployed in the public sphere often construct pasts that are more practical than historical and that are driven as much by the need to locate and motivate their authors’ positions in present debates as by the desire to understand the past itself.

One influential trope organizing practical historical pasts in England has been ‘the New History,’ a term that denotes the replacement of highly didactic narrative-based pedagogies with approaches to teaching and learning organised through enquiry and the use of historical sources. Schematising somewhat, we can identify two mirror-image narrativisations of this trope that have been frequently deployed to support or to criticise the status quo.

Template 1: Neotraditional ‘declinist’ narratives

For critics of ‘the New History’, such as Derek Matthews, all was well in history education before the late 1960s when progressive theorists precipitated decline by implementing misguided reforms.[5] This narrativisation functions as a call to arms to roll back unwelcome changes and return to a ‘better’ past.

Template 2: Reforming ‘progressivist’ narratives

The narratives of those who identify with or advocate ‘the New History’ reform, such as David Sylvester, tend to position school history as in a very poor state before the late 1960s when progressive educationalists are said to have introduced dramatically new approaches to history education that saved history from irrelevance and that revived it.[6]

Both these narrative schematizations note something important – there was significant change in history education in the late 1960s and early 1970s, best exemplified in the Schools Council History Project (SCHP).[7] However, as the historian of education Richard Aldrich has pointed out, they are too neat and draw much too stark a line between past and present – there were numerous cases of ‘new’ history before the SCHP and, as Peter Lee has argued, ‘the’ new history is a simplification that lumps together at least three different positions on the nature and aims of history education.[8] A further objection to both narrativisations is that they interpret the past using our contemporary categories to measure presence and absence, mirroring present concerns more than past realities.

School History, Suggestion and Hypnotism

Where practical pasts are presentist, disciplinary history aims to be historicist — to understand the past in terms that made sense in the past. Thus, Peter Yeandle’s detailed historical investigation of English history teaching between the 1870s and the 1930s has shown that educational theory — the ‘villain’ of the 1960s in neo-traditionalist tales — was central to educational practice in the Edwardian period but that this ‘theory’ had forms and value commitments that we might not expect, thinking present-centredly.[9]

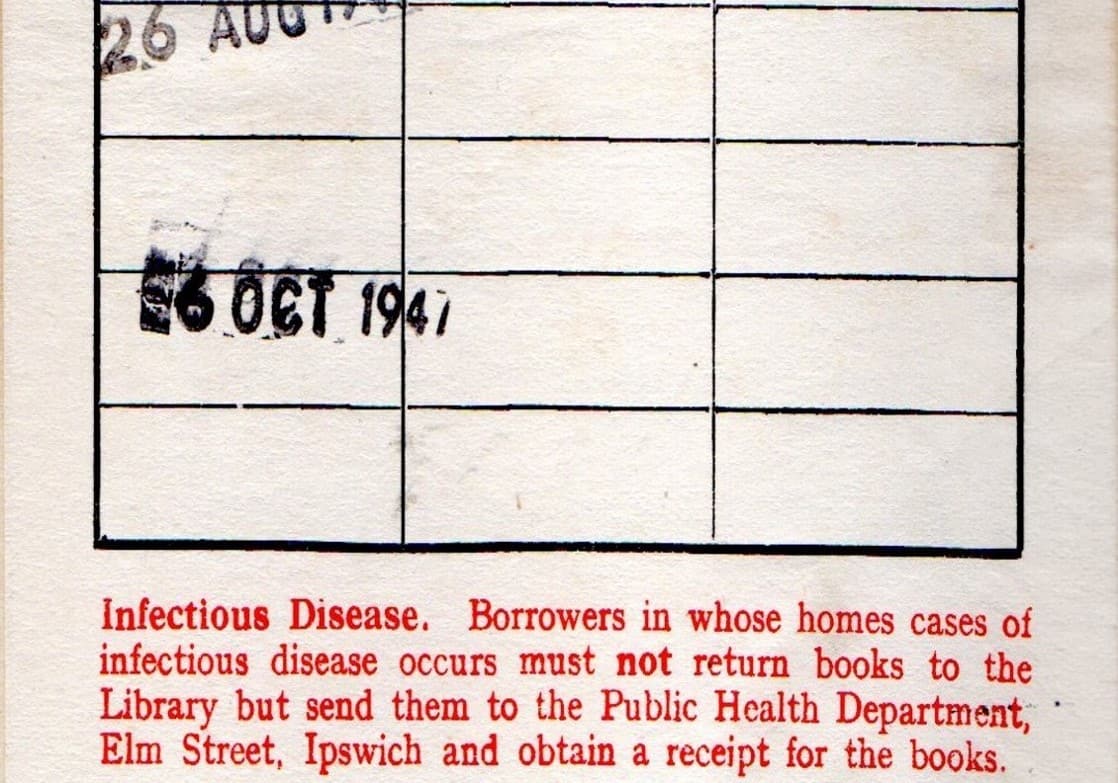

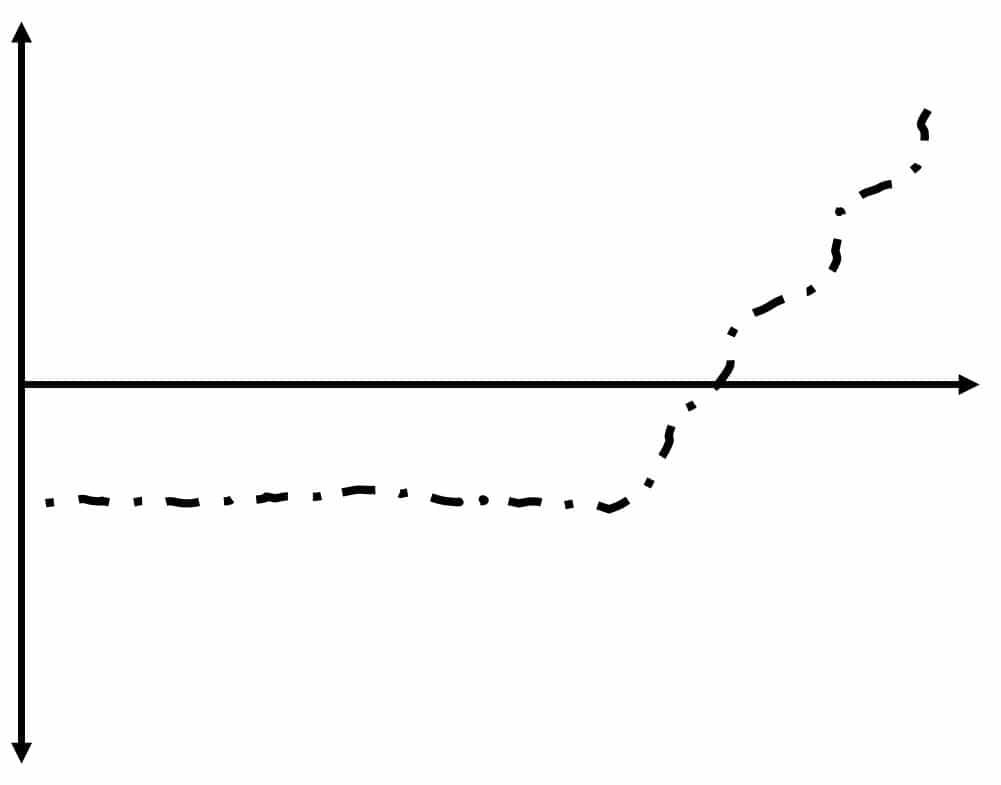

A few years back, at the height of recent English history wars, I was given a discontinued library book, a 1913 edition of Maurice Keatinge’s Studies in the Teaching of History. Where Keatinge (1868-1935) figures in history education’s practical pasts it is typically as a ‘precursor’ — someone who attempted a ‘New History’-style document-based approach ahead of its time. In many ways, this seems an apt description; Studies is, primarily, about developing rigorous historical thinking in schools using historical documents. However, this is to read Keatinge anachronistically — his work is of its time not ours and we should expect it to have a distinctive conceptual architecture. This fact is present in the text itself, as the library issuing-stamp page in the book shows: Studies comes from a world in which books were regularly quarantined and — perhaps — fumigated to control infectious disease.

Reading Studies and other Keatinge books — such as Suggestion in Education, a book on hypnotism — makes it clear that Keatinge’s rationale for using documents is as distant from our contemporary practice as book quarantining is. For Keatinge, the purpose of school history was to build citizens more than it was to build disciplinary thinkers. He thought that this could not be done by telling children uplifting stories — hypnotism research showed that students would react in a ‘contrariant’ manner to such an approach and that narrative was not enough. ‘Suggestion’ rather than explicit instruction, was needed, Keatinge claimed, and distracting children with a difficult task (document analysis) would encourage them to treat history seriously. It would also absorb their attention whilst the content and themes of the documents would help to shape their thinking in the ways educators might want from a citizenship perspective without the students being aware of this.[9]

Against Analogy

Using history for practical purposes in the present has value. History education should, however, think historically about history teaching. Although drawing analogies with the past can be informative, attending to its specific difference is critical. It is only by recognising conceptual and practical discontinuities between pasts and the present that we can truly appreciate both the identities of the past and the specific challenges of our own times.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Aldrich, Richard. Lessons from History of Education: The selected works of Richard Aldrich. London: Routledge, 2011.

- Lee, Peter J. “Fused horizons? UK research into students’ second-order ideas in history — A perspective from London.” In Researching history education: International perspectives and disciplinary traditions, ed. Manuel Köster, Holger Thünemann and Meik Zülsdorf-Kersting, 170–194. Schwalbach: Wochenschau Verlag, 2014.

Web Resources

- Institute of Historical Research. “History in education: About the project.” http://history.ac.uk/history-in-education/ (last accessed on 27 October 2017).

- History of Education Society. http://historyofeducation.org.uk/ (last accessed on 27 October 2017).

_____________________

[1] David Lowenthal, The Past is a Foreign Country (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

[2] Peter Seixas, “A History/Memory Matrix for History Education,” Public History Weekly 4, no. 6 (2016): DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-5370 (last accessed on 19 October 2017); Herman Paul, Key Issues in Historical Theory (Abingdon: Routledge, 2015).

[3] Seixas, A History/Memory Matrix for History Education.

[4] Sam Leith, “You Talkin’ To Me?”: Rhetoric from Aristotle to Obama (London: Profile Books, 2012).

[5] Derek Matthews, The strange death of history teaching (fully explained in seven easy-to-follow lessons) (Cardiff: self-published, 2009).

[6] David Sylvester, “Change and continuity in history teaching 1900–1993,” in Teaching History, ed. Hilary Bourdillon (London: Routledge, 1994), 9–25.

[7] Denis Shemilt, History 13–16 Evaluation Study (Edinburgh: Holmes McDougall, 1980).

[8] Richard Aldrich, Lessons from History of Education: The selected works of Richard Aldrich (London: Routledge, 2011); Peter J. Lee, “Fused horizons? UK research into students’ second-order ideas in history — A perspective from London,” in Researching history education: International perspectives and disciplinary traditions, ed. Manuel Köster, Holger Thünemann and Meik Zülsdorf-Kersting (Schwalbach: Wochenschau Verlag, 2014), 170–194.

[9] Peter Yeandle, Citizenship, Nation, Empire: The Politics of History Teaching in England 1870–1930 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015).

[10] Maurice Walter Keatinge, Studies in the Teaching of History (London: Adam and Charles Black, 1913); Maurice Walter Keatinge, Suggestion in Education (London: Adam and Charles Black, 1911).

_____________________

Image Credits

Library issuing-stamp page in a copy of Maurice Keatinge’s Studies in the Teaching of History (1913) © Arthur Chapman (2017).

Recommended Citation

Chapman, Arthur: Make It Strange — History as an Enigma, not a Mirror. In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 37, DOI:dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10381.

GeschichtslehrerInnen weisen – und aus meiner Sicht zu Recht – auf die Bedeutung des historischen Wissens und Denkens für unsere kollektiven Vergangenheiten hin. Sollen wir also von der historischen Bildung ein verstärktes Bewusstsein für die eigene Vergangenheit erwarten und welche Art von Verbindung zur Vergangenheit können wir uns dabei erhoffen?

Verbindungen zur Vergangenheit

TheoretikerInnen, die sich mit dem Thema Geschichtsbewusstsein beschäftigen, haben darauf hingewiesen, dass es mehrere Arten von Verbindungen zur Vergangenheit gibt. Der eine Ansatz befasst sich mit Erinnerung und Identifikation; der andere stuft die Vergangenheit als fremdartig und alltagsfern ein und beschäftigt sich zudem mehr mit dem Formulieren neuer und methodisch-stabiler Aussagen über die Vergangenheit als mit gegenwartsbejahenden Wahrnehmungen.[1] Dies ist eine merkwürdige Unterteilung, denn “es ist allgemein anerkannt, dass so etwas wie ‘reine Geschichte’ nicht existiert: eine Wissenschaft frei von den Eigenschaften des kollektiven Gedächtnisses”.[2] Trotzdem macht es analytisch gesehen Sinn, Unterscheidungstypen, sei es ästhetischer, ethischer oder materieller Natur, auseinanderzuhalten. So wird die Selbstwahrnehmung der Pluralität der vergangenheitsorientierten Praktiken, deren Zweck und zahlreiche Angebotscharakter und Restriktionen verstärkt.[3]

In Diskussionen über historische Bildung wird zwischen Geschichte und Erinnerung unterschieden, um Curricula unterschiedlich zu betrachten. Diese Unterscheidung kann auch eine reflexive und kritische Haltung unter GeschichtslehrerInnen fördern, wenn sich diese mit der Geschichte ihres Faches auseinandersetzen. Anhand von zwei praktisch-historischen Narrativen der historischen Bildung in England werde ich dies verdeutlichen. Zudem verweise ich auf ein Beispiel, bei dem die fachwissenschaftliche Beschäftigung mit der Vergangenheit solchen Narrativen entgegenwirkt.

Narrative des Niedergangs und des Triumphs

Debatten über die historische Bildung in England werden oft polarisiert und von einer Art “Dialyse” deformiert – einer rhetorischen Trope, die durch “entweder/oder”- und “wir/sie”-Dichotomien fortbesteht und die versucht, diese neu zu kreieren und zu vertiefen.[4] Die Geschichten, die in der historischen Bildung transportiert werden und in der Öffentlichkeit kursieren, konstruieren oft Vergangenheiten in einem eher praktischen als historischen Verständnis. Sie sind ebenso sehr vom Bedürfnis geleitet, die Positionen der AutorInnen in gegenwärtigen Debatten zu festigen, wie auch vom Verlangen, die Vergangenheit selbst zu verstehen.

Eine Trope, die den praktischen Umgang mit Vergangenheit in England prägt, nennt sich “New History” – ein Begriff, der die Ablösung einer didaktischen, narrativorientierten Pädagogik durch Lehr- und Lernansätze, die auf Recherchen und den Gebrauch historischer Quellen beruhen, umschreibt. Es können zwei spiegelbildliche Narrative dieser Trope identifiziert werden, um den Status quo zu unterstützen bzw. zu kritisieren.

Neotraditionales Narrativ der Ablehnung

Für KritikerInnen der “New History”, etwa Derek Matthews, wurde in den 1960er Jahren durch fehlgeleitete Reformen progressiver TheoretikerInnen der Niedergang der historischen Bildung eingeläutet.[5] Diese Erzählung fungiert als Weckruf, um Veränderungen rückgängig zu machen bzw. um zu einer “besseren” Vergangenheit zurückzukehren.

Progressives Narrativ der Befürwortung

BefürworterInnen der “New History”-Reform, etwa David Sylvester, rücken die schulische historische Bildung bis in die späten 1960er Jahre in ein eher schlechtes Licht. Durch neue Ansätze hätten progressive DidaktikerInnen entscheidend dazu beigetragen haben, die Geschichte vor Irrelevanz zu retten und wiederzubeleben.[6]

Beide Narrative weisen eine bedeutende Eigenschaft auf: In den späten 1960er und frühen 1970er Jahren gab es einen Wandel in der historischen Bildung, der sich am Beispiel des Schools Council History Projects (SCHP) zeigt.[7] Wie Richard Aldrich jedoch erläutert, sind diese Narrative übergenau und zeigen einen zu starken Kontrast zwischen Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. Außerdem gab es bereits vor dem SCHP zahlreiche Beispiele für “neue” Geschichte. Wie Peter Lee erörtert, ist “die” neue Geschichte ein inadäquater Begriff, der mehrere Ansätze der historischen Bildung kombiniert.[8] Ferner wird den beiden Narrativen vorgeworfen, die Vergangenheit mit Hilfe zeigenössischer Kategorien zu interpretieren, um An- und Abwesenheit zu messen, indem sie mehr aktuelle Anliegen als Vergangenes widerspiegeln.

Schulgeschichte, Vorschläge und Hypnose

Während die “praktische Geschichte” gegenwartsorientiert ist, versucht die “disziplinäre Geschichte” historistisch zu sein, d.h. dass Geschichte verstanden werden soll, indem man sich in Vergangenes hineinversetzt. Peter Yeandles Untersuchung des englischen Geschichtsunterrichts zwischen den 1870er und den 1930er Jahren zeigt, dass die Pädagogik eine zentrale Rolle in Bildungspraktiken der Edwardianischen Epoche spielte. Jedoch beinhaltete die pädagogische “Theorie” Formen und Werte, die wir aus heutiger Sicht nicht erwartet hätten.[9]

Vor ein paar Jahren, am Höhepunkt der englischen “history wars“, wurde mir ein ausrangiertes Bibliotheksbuch überreicht – eine 1913 erschienene Edition von Maurice Keatinges Studies in the Teaching of History. In der “praktischen Vergangenheit” des Geschichtsunterrichts fungiert Keatinge (1868–1935) eigentlich als Vorläufer, indem er den quellenorientierten Ansatz der “New History” umzusetzen versuchte und das historische Denken an Schulen durch die Verwendung historischer Quellen zu entwickeln versuchte. Dies wäre allerdings eine anachronistische Interpretation zu Keatinge – sein Werk stammt nicht aus unserer Zeit, weshalb wir von ihm eine konzeptuelle Struktur erwarten. Diese Tatsache lässt sich im Text anhand eines Ausleihvermerks der Bibliothek im Buch selbst feststellen: Studies stammt aus einer Zeit, in der Bücher der Quarantäne unterzogen und ausgeräuchert wurden, um ansteckende Krankheiten einzudämmen. Studies und andere Bücher Keatinges wie Suggestion in Education, ein Buch über Hypnose, verdeutlichen, dass Keatinges Argument, Dokumente zu verwenden, uns so fern ist wie die Buchquarantäne.

Keatinge zufolge sollte der Geschichtsunterricht eher MusterbürgerInnen als FachwissenschafterInnen ausbilden. Er war der Überzeugung, dass dies nicht durch die kindgerechte Erzählung von Geschichten erreicht werden könne. Die Hypnoserecherche ergab, dass SchülerInnen auf einen solchen Ansatz konträr reagierten und dass Narrative allein nicht genügten. Keatinge forderte Aufgabenstellungen anstatt expliziter Anweisungen. Die Beschäftigung von Kindern mit einer schwierigen Aufgabe (der Dokumentanalyse) würde sie ermutigen, die Geschichte ernst zu nehmen. Dies würde außerdem ihre Aufmerksamkeit wecken und der Inhalt und die Themen der Dokumente zudem zur Entwicklung ihrer Denkweisen beitragen – und zwar so, wie LehrerInnen es aus der Perspektive bürgerlicher Erziehung, ohne das Wissen der SchülerInnen, erstreben würden.[10]

Gegen die Analogie

Die praktische Verwendung von Geschichte liegt im Interesse der Gegenwart. Die historische Bildung sollte in ihrer historischen Dimension wahrgenommen werden. Obwohl es informativ sein kann, Vergleiche mit der Vergangenheit zu ziehen, ist es entscheidend, auf die Unterschiede einzugehen. Nur durch das Wahrnehmen konzeptueller und praktischer Diskontinuitäten zwischen Vergangenheiten und der Gegenwart können wir sowohl die Identitäten der Vergangenheit als auch die Herausforderungen unserer Zeit schätzen.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Aldrich, Richard. Lessons from History of Education: The selected works of Richard Aldrich. London: Routledge, 2011.

- Lee, Peter J. “Fused horizons? UK research into students’ second-order ideas in history — A perspective from London.” In Researching history education: International perspectives and disciplinary traditions, Hrsg. Manuel Köster, Holger Thünemann und Meik Zülsdorf-Kersting, 170–194. Schwalbach: Wochenschau Verlag, 2014.

Webressourcen

- Institute of Historical Research. “History in education: About the project.” http://history.ac.uk/history-in-education/ (letzter Zugriff am 27.10.2017).

- History of Education Society. http://historyofeducation.org.uk/ (letzter Zugriff am 27.10.2017).

_____________________

[1] David Lowenthal, The Past is a Foreign Country (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

[2] Peter Seixas, “Eine Geschichts-/Gedächtnis-Matrix für den Geschichtsunterricht,” Public History Weekly 4, no. 6 (2016): DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2016-5370 (letzter Zugriff am 19.10.2017); Herman Paul, Key Issues in Historical Theory (Abingdon: Routledge, 2015).

[3] Seixas, “Eine Geschichts-/Gedächtnis-Matrix”.

[4] Sam Leith, “You Talkin’ To Me?”: Rhetoric from Aristotle to Obama (London: Profile Books, 2012).

[5] Derek Matthews, The strange death of history teaching (fully explained in seven easy-to-follow lessons) (Cardiff: Eigenveröffentlichung, 2009).

[6] David Sylvester, “Change and continuity in history teaching 1900–1993,” in Teaching History, Hrsg. Hilary Bourdillon (London: Routledge, 1994), 9–25.

[7] Denis Shemilt, History 13–16 Evaluation Study (Edinburgh: Holmes McDougall, 1980).

[8] Richard Aldrich, Lessons from History of Education: The selected works of Richard Aldrich (London: Routledge, 2011); Peter J. Lee, “Fused horizons? UK research into students’ second-order ideas in history — A perspective from London,” in Researching history education: International perspectives and disciplinary traditions, Hrsg. Manuel Köster, Holger Thünemann und Meik Zülsdorf-Kersting (Schwalbach: Wochenschau Verlag, 2014), 170–194.

[9] Peter Yeandle, Citizenship, Nation, Empire: The Politics of History Teaching in England 1870–1930 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015).

[10] Maurice Walter Keatinge, Studies in the Teaching of History (London: Adam and Charles Black, 1913); Maurice Walter Keatinge, Suggestion in Education (London: Adam and Charles Black, 1911).

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

Bibliotheksstempel in einem Exemplar von Maurice Keatinges Studies in the Teaching of History (1913) © Arthur Chapman (2017).

Übersetzung

Stefanie Svacina and Paul Jones (paul.stefanie at outlook.at)

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Chapman, Arthur: Make It Strange – Geschichte als Mythos, nicht als Reflexion. In: Public History Weekly 5 (2017) 37, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10381.

Copyright (c) 2017 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 5 (2017) 37

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2017-10381

Tags: Analogies (Vergleiche), History Teaching (Geschichtsunterricht), Narratives (Narrative), UK (Grossbritannien)