Abstract: Imagine you are in school and asked to write down, in a page or two, the history of your country, your nation or your homeland (patria) as you know it. While this task may sound trivial, it tells us some important facets of people’s ability to use knowledge of the past for constructing a meaningful historical narrative.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2015-3819.

Languages: English, Deutsch, Français

Imagine you are in school and asked to write down, in a page or two, the history of your country, your nation or your homeland (patria) as you know it. While this task may sound trivial, it tells us some important facets of people’s ability to use knowledge of the past for constructing a meaningful historical narrative.[1]

A bunch of “stuff” that needs to be remembered

From a practical, pedagogical standpoint, historical narratives matter for at least three reasons:

– Historical narratives represent the linguistic and structural form with which it becomes possible for people to organize the “course of time” in a coherent way, thus giving everyday life a temporal frame and matrix of historical orientation.

– Historical narratives serve to establish the identity of their authors and their audience. Whether the historical narrative is from the family, the school or the community, it comprises a continuous temporal experience, from the past to the present, making it possible for people to situate themselves – individually and collectively – in reference to others in the course of time.

– Historical narratives give people reasons for action. Although a historical narrative is primarily aimed at making sense of past realities, its purpose is to orient life in time in a way which confers upon past actualities a possible future perspective. As such, historical narratives serve to define an imaginable course of actions for individuals and groups guided by the agency of historical knowledge and memory.[2]

This narrative approach to history departs significantly from what typically captures media headlines in my country: “Canada’s failing history.” For the most past, studies in the field of history education have traditionally been concerned with what students know (or don’t know) about the past in relation to canonical knowledge and prescribed curriculum expectations. Annual exams and recurring surveys of young people’s historical knowledge dominate public debate and fuel “history wars.” Unfortunately, These “tests” tell us very little about the significant aspects and specific realities of the past that students acquire, internalize, and use to orient their life and make sense of their world. Years of schoolings and standardized testing have conditioned students – and adults – to believe that history is about a bunch of “stuff” that needs to be remembered or alternatively retrieved instantly from the Internet.

Historical narrative and consciousness

But historical narratives are more complex than aggregated bits of “stuff” and do not emerge spontaneously. They are developed gradually over the course of time as a result of an internalization process by which “individuals acquire beliefs, attitudes, or behavioral regulations from external sources”[3] and progressively transform those external regulations into their personal “historical consciousness.” First devised by German scholars decades ago, and still relatively new to North American scholarship, the concept of historical consciousness goes beyond the accumulation of historical knowledge in memory. It takes into account the mental reconstruction and appropriation of historical information and experiences – acquired at home, in the community, in school, and in popular culture – that are brought into the mental household of an individual.[4] This concept involves a complex process of combining the past, the present, and the envisioned future into meaningful and sense-bearing time. For German historian Jörn Rüsen, historical consciousness serves the reflexive and practical function of orienting our life in time, thus offering narrative visions – big pictures – to guide our contemporary actions and moral behaviors in reference to a usable past.[5]

Students’ history knowledge

If, as French philosopher Paul Ricoeur contends, “time becomes human time to the extent that it is organized after the manner of a narrative,”[6] then we have to be far more attentive to the various narratives that students acquire and tell. Studies, and including our ones, suggest that young people tend to develop “simplified narratives” of the past which, in the words of Denis Shemilt, are “event-space” changes separated by long periods of quiescence in which nothing happens.[7] Students typically compress the collective past into a limited series of historical happenings as if history was like a volcano “occasionally convulsed by random explosions.”[8] These narrative simplifications of the collective past often develop very early in life and can prove to be very robust because they act as “heuristics” and mental frameworks for structuring new learning. So unless these simplified narratives are problematized in school, young people’s historical consciousness is unlikely to be transformed by formal history education alone.

In fact, in their intergenerational study assessing young Americans’ historical consciousness, Wineburg et al. discovered that by restricting our notions of history to the official knowledge of the state-sponsored curriculum, we completely escape the powerful external forces that permeate the historical narratives acquired by today’s youth. In their view, this “cultural Curriculum” can prove to be “more powerful in shaping young people’s ideas about the past than the mountains of textbooks that continue to occupy historians’ and educators’ attention.”[9]

Challenging students’ historical narratives

Today, most teachers are aware of the theory of constructivism and the need to consider the learner’s prior knowledge. But students are rarely assessed on their own historical narratives of the collective past. Rather, teachers typically designed assessment tools meant to gather information on the various learning expectations of the curriculum that students are supposed to master. As a result, students in countries like Canada have no pedagogically-structured opportunity in school to express and confront their pre-conceived knowledge and simplified stories acquired from the “real-life” cultural curriculum and that they bring to formal classroom learning.

As a history educator, I consider it important that we challenge students’ own historical narratives. If school is to play a significant role in shaping the education of young citizens, I believe it must find new ways to engage and make more complex their narrative visions of the past – to provide them with multifaceted “big Pictures” of the past. One way to do so is precisely to invite them to write their own stories of the past, as they know it. Failing to do so will deprive educators of one of the most fundamental means that people use to make sense of the past for contemporary meaning-making.[10]

_____________________

Further Reading

- Bruner, Jerome, ‘Narrative and paradigmatic modes of thought,’ in Elliot Eisner (ed.), ‘Learning and Teaching the ways of knowing,’ Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1985, p. 97-115.

- Carr, David, ‘Time, narrative and history,’ Indiana: Indiana University Press 1986.

- Ricoeur, Paul, ‘Time and narrative,’ 2 vols, Chicago: Univerity of Chicago Press 1984.

Web Resources

- Centre for the Study of Historical Consciousness. The University of British Columbia: http://www.cshc.ubc.ca (last accessed 30.03.2015).

- Historical Encounters, Journal of historical consciousness, historical culture and history education: http://hej.hermes-history.net (last accessed 30.03.2015).

____________________

[1] The author would like to thank doctoral student Raphaël Gani (rgani011@uottawa.ca) for his insightful comments and feedback on drafts of this article.

[2] J. H. Liu, & D. J. Hilton, “How the Past Weighs on the Present: Social Representations of History and Their Role in Identity Politics,” The British Journal of Social Psychology, 44(2005), 537–556.

[3] W. Grolnick, E. Deci and R. Ryan, “Internalization within the family: The self-determination theory perspective” as quoted in James Wertsch, Voices of collective remembering (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 121.

[4] See P. Seixas (ed.), “Theorizing historical consciousness” (Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2004); J. Rüsen, “History: Narration, interpretation, orientation” (New York, NY: Berghahn Books, 2005); and J. Létourneau, Je me souviens ? Le passé du Québec dans la conscience de sa jeunesse (Montréal, QC: Fides 2014).

[5] Rüsen, History: Narration, interpretation, orientation, 25.

[6] Ricoeur, Time and Narrative, 3.

[7] See B. VanSledright and J. Brophy, “Storytelling, imagination, and fanciful elaboration in children’s historical reconstructions,” American Educational Research Journal, 29 (1992), 837-859; K. Barton, “Narrative simplifications in elementary students’ historical thinking,” in J. Brophy (ed.), “Advances in Research on Teaching,” vol. 6 (Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 1996), 51-84; D. Shemilt, “The Caliph’s Coin: The currency of narrative frameworks in history teaching,” in P. Seixas, P. Stearns, and S. Wineburg (eds.), “Knowing and teaching history: National and international perspectives” (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2000), 83-101; S. Lévesque, J. Létourneau, and R. Gani. “A Giant with Clay Feet: Québec Students and Their Historical Consciousness of the Nation.” International Journal of Historical Learning, Teaching and Research 11, 2 (2013); M. Robichaud, “L’histoire de l’Acadie telle que racontée par les jeunes francophones du Nouveau-Brunswick : construction et déconstruction d’un récit historique,” Acadiensis 40, 2 (2011): 33-69 ; and J. Létourneau and S. Moisan, “Mémoire et récit de l’aventure historique du Québec chez les jeunes Québécois d’héritage canadien-français: coup de sonde, amorce d’analyse des résultats, questionnement,” Canadian Historical Review 84, 2 (2004): 325-357.

[8] D. Shemilt, “History 13-16: Evaluation Study” (Edinburgh, UK: Holmes McDougall, 1980), 35.

[9] S. Wineburg, S. Mosborg, D. Porat, and A. Duncan, “Forrest Gump and the future of teaching history,” Phi Delta Kappan (November 2007), 176.

[10] On the importance of the narrative structure for the mind and history, see, for example, B. Hardy, “Narrative as a primary act of mind,” in M. Meek, A. Warlow, and G. Barton, The Cool Web: The pattern of children’s reading (London, UK: Bodley Hean, 1977), 135-141; P. Ricoeur, Time and Narrative, vol. I (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983); D. Carr, Time, Narrative and History (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986); and J. Bruner, “Narratives and paradigmatic modes of thought,” in E. Eisner (ed.), Learning and teaching the ways of knowing (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1985), 97-115.

_____________________

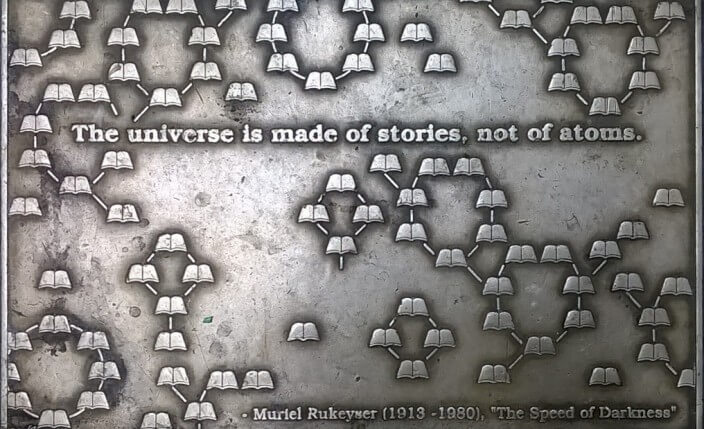

Image Credits

© Lesekreis. Wikimedia Commons (public Domain).

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ALibrary_Walk_6.JPG

Recommended Citation

Levesque, Stéphane: Why historical narrative matters? Challenging the stories of the past. In: Public History Weekly 2 (2015) 11, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2015-3819.

Stellen Sie sich vor, Sie seien in der Schule und würden gebeten, auf ein bis zwei Seiten die Geschichte Ihres Landes, Ihrer Nation oder Ihrer Heimat (patria) so niederzuschreiben, wie Sie diese kennen. Während diese Aufgabe vielleicht trivial klingt, zeigt uns das Resultat doch wichtige Facetten der individuellen Fähigkeit, das Wissen über die Vergangenheit in ein sinnvolles historisches Narrativ zu überführen.[1]

Ein Bündel “Zeugs”, das man sich merken muss

Von einem praktischen, pädagogischen Standpunkt aus betrachtet, sind historische Narrative aus mindestens drei Gründen bedeutsam:

– Historische Narrative repräsentieren die linguistische und strukturelle Form, die es uns ermöglicht, den “Verlauf der Zeit” in einer kohärenten Weise darzustellen, was wiederum dem Alltag einen zeitlichen Rahmen und eine Matrix historischer Orientierung verleiht.

– Historische Narrative dienen der Herausbildung einer Identität für ihre VerfasserInnen und deren Publikum. Ob es sich um das historische Narrativ einer Familie, einer Schule oder einer Gemeinde handelt: Es umfasst eine fortlaufende Zeiterfahrung, die sich von der Vergangenheit bis zur Gegenwart erstreckt. Damit ermöglichen Narrative den Menschen, sich individuell und kollektiv in Bezug zu anderen und der fortschreitenden Zeit zu situieren.

– Historische Narrative liefern eine Handlungsbegründung. Obwohl ein historisches Narrativ vorwiegend darauf abzielt, der vergangenen Wirklichkeit Sinn zu verleihen, ist sein Zweck doch vor allem, in einer Art und Weise der eigenen Existenz in der Zeit Orientierung zu vermitteln, die der vergangenen Wirklichkeit eine mögliche zukünftige Perspektive gewährt. Als solche dienen historische Narrative Personen und Gruppen dazu, vorstellbare Handlungsmöglichkeiten zu definieren vermittels historischen Wissens und Erinnerung.[2]

Dieser narrative Ansatz unterscheidet sich erheblich von dem, was als typische Überschrift in den Medien meines Landes zu lesen ist: “Kanada versagt in Geschichte”. In der Vergangenheit waren die meisten Studien auf dem Gebiet der Geschichtsdidaktik traditionellerweise darüber besorgt, was SchülerInnen von der Vergangenheit wissen (oder nicht wissen). Bezugsgröße war dabei das kanonische Wissen und die in Lehrplänen vorgeschriebenen Anforderungen. Jährliche Prüfungen und wiederkehrende Überprüfungen des historischen Wissens junger Leute dominieren den Diskurs in der Öffentlichkeit und befeuern “Geschichtskriege”. Leider berichten uns diese “Tests” sehr wenig über die wichtigsten Aspekte und die spezifischen Vorstellungen von der Vergangenheit, die von den SchülerInnen erworben, verinnerlicht und angewendet werden, um sich im Leben zu orientieren und ihrer Welt Sinn zu verleihen. Jahrelange Beschulung und standardisierte Testung hat die SchülerInnen – und die Erwachsenen – dazu konditioniert zu glauben, dass Geschichte ein Bündel von “Zeugs” ist, das man sich merken muss oder alternativ sofort aus dem Internet abrufen kann.

Historisches Narrativ und Bewusstsein

Historische Narrative sind jedoch komplexer als zusammengewürfelte Häppchen von “Zeugs” und entstehen nicht spontan. Sie werden nach und nach als Folge eines Internalisierungsprozesses erworben, in dem sich “Individuen Überzeugungen, Einstellungen oder Verhaltensweisen von externen Einflüssen aneignen”[3] und nach und nach aus diesen externen Vorgaben in ihrer persönlichen Entwicklung ein “Geschichtsbewusstsein” ausbilden. Dieses wurde bereits vor Jahrzehnten von deutschen WissenschaftlerInnen beschrieben, ist aber im nordamerikanischen Wissenschaftsdiskurs noch immer vergleichsweise neu. Das Konzept des Geschichtsbewusstseins geht über die Anhäufung historischen Wissens im Gedächtnis hinaus. Es berücksichtigt die mentale Verarbeitung und die Aneignung historischen Wissens und Erfahrungen – erworben im häuslichen Umfeld, im öffentlichen Leben, in der Schule oder im Zuge der Populärkultur – die nun in den mentalen Haushalt des Individuums mit eingebracht werden.[4] Dieses Konzept umfasst einen komplexen Prozess der Kombination von Vergangenheit, Gegenwart und vorgestellter Zukunft in eine sinnvolle und sinnführende Vorstellung von Zeit. Für Jörn Rüsen dient Geschichtsbewusstsein der reflexiven und angewendeten Funktion, das Leben hinsichtlich der Zeit zu orientieren. Es bietet damit narrative Vorstellungen – das große Ganze –, um gegenwärtige Handlungsweisen und moralische Verhaltensweisen mit Bezug auf eine dafür nutzbare Vergangenheit anzuleiten.[5]

Schülervorstellungen von Geschichte

Wenn, wie der französische Philosoph Paul Ricoeur behauptet, “Zeit in dem Maße zur menschlichen Zeit wird, wie sie im Sinne einer Erzählung organisiert wird”,[6] dann müssen wir weit mehr Aufmerksamkeit den verschiedenen Narrativen widmen, die SchülerInnen entwickeln und erzählen. Studien, einschließlich unserer, deuten darauf hin, dass junge Menschen dazu neigen, “vereinfachte Narrative” der Vergangenheit zu entwickeln, die, in den Worten von Denis Shemilt, Veränderungen in einem “Ereignisraum” zwischen langen Ruheperioden darstellen, in denen nichts passiert.[7] In der Regel komprimieren SchülerInnen die kollektive Vergangenheit in eine limitierte Abfolge von historischen Ereignissen, als wäre die Geschichte ein Vulkan, der “gelegentlich durch zufällige Explosionen ausbricht”.[8] Diese vereinfachten Narrative der kollektiven Vergangenheit entwickeln sich oftmals sehr früh im Leben und erweisen sich als äußerst robust, da sie als “heuristische” und mentale Strukturen das neu Gelernte ordnen. Falls diese vereinfachten Narrative nicht in der Schule problematisiert werden, ist es sehr unwahrscheinlich, dass sich das Geschichtsbewusstsein junger Menschen durch formalen Geschichtsunterricht allein verändern lässt.

In der Tat zeigen Wineburg et al. in ihrer generationsübergreifenden Studie zum Geschichtsbewusstsein junger AmerikanerInnen, dass durch die Beschränkung unserer Vorstellungen von Geschichte auf das offiziell bestätigte Wissen der Lehrplaninhalte, uns die mächtigen äußeren Einflüsse völlig entgehen, die die historischen Narrative der heutigen Jugend beeinflussen. Ihrer Meinung nach könnte sich dieser “kulturelle Lehrplan” als “einflussreicher bei der Herausbildung von Vorstellungen über die Vergangenheit von jungen Leuten herausstellen als die Berge von Schulbüchern, die weiterhin die Aufmerksamkeit von Historikern und Pädagogen besetzen.”[9]

Förderung der historischen Narrative bei SchülerInnen

Heutzutage sind sich die meisten Lehrpersonen der Theorie des Konstruktivismus bewusst und wissen um die Notwendigkeit, das Vorwissen der Lernenden zu berücksichtigen. Allerdings werden bei den Lernenden kaum deren eigenen historischen Narrative über die kollektive Vergangenheit bewertet. Sie werden vielmehr regelmäßig von ihren Lehrpersonen mit eigens dafür entwickelten Bewertungsinstrumenten konfrontiert, die der Überprüfung der Lernerwartungen des Lehrplans dienen, deren Meisterung von den Lernenden erwartet wird. Aus diesem Grund haben SchülerInnen in Ländern wie Kanada keine pädagogisch strukturierte Möglichkeit, sich mit ihrem vorgefassten Wissen und ihren einfachen Narrativen, die sie im kulturellen Curriculum des Alltags erworben haben, im Rahmen schulischen Lernens auseinanderzusetzen.

Als Geschichtsdidaktiker halte ich es für wichtig, von den SchülerInnen eine Auseinandersetzung mit ihren eigenen historischen Narrativen zu verlangen. Wenn die Schule eine bedeutende Rolle bei der Bildung junger BürgerInnen spielen soll, dann muss sie neue Wege finden, sich mit den narrativen Vorstellungen der Jugendlichen auseinander zu setzen und diese komplexer zu machen – um sie dadurch mit vielfältigen “Gesamtsichten” der Vergangenheit zu versorgen. Eine Möglichkeit wäre eben, sie dazu zu ermutigen, ihre eigenen Narrative über die Vergangenheit, so wie sie sie kennen, zu schreiben. Dies zu versäumen, entzieht den Lehrpersonen eines der grundlegendsten Mittel, mit dem Menschen für gewöhnlich der Vergangenheit Sinn verleihen, um sich zur Meinungsbildung in der Gegenwart zu befähigen.[10]

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Bruner, Jerome: Narrative and paradigmatic modes of thought, in: Elliot Eisner (Hrsg.): Learning and Teaching the ways of knowing. Chicago, S. 97-115.

- Carr, David: Time, narrative and history. Indiana 1986.

- Ricoeur, Paul: Time and narrative, 2 Bd., Chicago 1984.

Webressourcen

- Centre for the Study of Historical Consciousness. The University of British Columbia: http://www.cshc.ubc.ca (last accessed 30.03.2015).

- Historical Encounters, Journal of historical consciousness, historical culture and history education: http://hej.hermes-history.net (last accessed 30.03.2015).

____________________

[1] Der Autor dankt dem Doktoranden Raphaël Gani (rgani011@uottawa.ca) für seine aufschlussreichen Kommentare und sein Feedback zu Entwürfen dieses Beitrages.

[2] J. H. Liu, D. J. Hilton: How the Past Weighs on the Present: Social Representations of History and Their Role in Identity Politics. In: The British Journal of Social Psychology 44 (2005), S. 537-556.

[3] W. Grolnick, E. Deci, R. Ryan: Internalization within the family: The self-determination theory perspective as quoted in James Wertsch, Voices of collective remembering. New York 2002, S. 121.

[4] Vgl. P. Seixas (Hrsg.): Theorizing historical consciousness. Toronto 2004; J. Rüsen: History: Narration, interpretation, orientation. New York 2005 und J. Létourneau: Je me souviens? Le passé du Québec dans la conscience de sa jeunesse. Montréal 2014.

[5] Rüsen, History: Narration, interpretation, orientation, S. 25.

[6] Ricoeur, Time and Narrative, S. 3.

[7] Vgl. B. VanSledright / J. Brophy: Storytelling, imagination, and fanciful elaboration in children’s historical reconstructions. In: American Educational Research Journal 29 (1992), S. 837-859; K. Barton: Narrative simplifications in elementary students’ historical thinking. In: J. Brophy (Hrsg.): Advances in Research on Teaching, Ausg. 6. Greenwich 1996, S. 51-84; D. Shemilt: The Caliph’s Coin: The currency of narrative frameworks in history teaching. In: P. Seixas, P. Stearns / S. Wineburg (Hrsg.): Knowing and teaching history: National and international perspectives. New York 2000, S. 83-101; S. Lévesque / J. Létourneau / R. Gani: A Giant with Clay Feet: Québec Students and Their Historical Consciousness of the Nation. In: International Journal of Historical Learning, Teaching and Research 11 (2013) 2; M. Robichaud: L’histoire de l’Acadie telle que racontée par les jeunes francophones du Nouveau-Brunswick: construction et déconstruction d’un récit historique. In : Acadiensis 40 (2011) 2, S. 33-69; und J. Létourneau / S. Moisan: Mémoire et récit de l’aventure historique du Québec chez les jeunes Québécois d’héritage canadien-français: coup de sonde, amorce d’analyse des résultats, questionnement. In: Canadian Historical Review 84 (2004) 2, S. 325-357.

[8] D. Shemilt: History 13-16: Evaluation Study. Edinburgh 1980, S. 35.

[9] S. Wineburg / S. Mosborg / D. Porat / A. Duncan: Forrest Gump and the future of teaching history. In: Phi Delta Kappan, Ausg. November 2007, S. 176.

[10] Zur Bedeutung der narrativen Struktur von Erinnerung und Geschichte vgl. z.B. B. Hardy: Narrative as a primary act of mind. In: M. Meek / A. Warlow / G. Barton: The Cool Web: The pattern of children’s reading. London 1977, S. 135-141; P. Ricoeur: Time and Narrative Ausg. 1. Chicago 1983; D. Carr: Time, Narrative and History. Bloomington 1986; und J. Bruner: Narratives and paradigmatic modes of thought. In: E. Eisner (Hsrg.): Learning and teaching the ways of knowing. Chicago 1985, S. 97-115.

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

© Lesekreis. Wikimedia Commons (gemeinfrei).

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ALibrary_Walk_6.JPG

Übersetzung aus dem Englischen

von Marco Zerwas

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Levesque, Stéphane: Was macht historische Narrative bedeutsam? Förderung der geschichtsbezogener Erzählkompetenz. In: Public History Weekly 3 (2015) 11, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2015-3819.

Imaginez que vous êtes de retour sur les bancs d’école et qu’on vous demande tout bonnement de raconter, en une page ou deux, l’histoire de votre pays, votre nation ou votre patrie comme vous la savez. Bien que cet exercice de mise en récit du passé peut vous sembler anodine, il n’en demeure pas moins révélateur de la capacité des gens à mobiliser certains savoirs historiques entassés dans la mémoire dans la construction de sens, d’une narration qui lien le passé au présent. [1]

Un “tas de choses” qu’on doit se rappeler

D’un point de vue pédagogique et pratique, on peut affirmer que les récits historiques revêtent une importance pour au moins trois raisons:

– Le récit historique permet d’établir l’identité de son auteur et de son auditoire. L’acte de raconter, qu’il procède de la famille, du milieu scolaire ou de la communauté d’appartenance, permet à l’individu de découvrir et d’établir sa propre identité historique en référence à un groupe, une communauté, un monde temporel qui se présente comme ordonné et dans lequel toutes les composantes du récit trouvent leur place dans la durée. Le récit attribue donc au passé un sens identitaire pour soi et pour les autres.

– Le récit historique représente la forme linguistique et structurelle grâce à laquelle il devient possible pour tout individu d’organiser de manière cohérente l’expérience chaotique du temps et ainsi donner un sens aux expériences de vie. C’est donc par la narration que le “temps devient temps humain”.

– Le récit historique favorise une mobilisation du passé pour l’action. Bien que le récit historique soit d’abord orienté vers la compréhension des réalités du passé, son but est une actualisation de ce passé dans le monde présent et l’avenir possible. Ainsi, par le récit l’individu peut donner un sens particulier aux dimensions du temps et par là même d’imaginer un avenir personnel et collectif, une sorte “d’horizon d’attente” guidé par une démarche comparative liant le passé au présent. Le récit se fait donc porteur d’une certaine vision de ce que pourrait être l’avenir de l’individu, du groupe, de la société.

Cette approche narrative de l’histoire est fort peu reconnue et considérée dans la compréhension qu’ont les autorités et les médias canadiens de l’apprentissage historique chez les jeunes, affirmant volontiers que ces derniers ne connaissent à peu près rien de l’histoire du Canada. Il est vrai que les études dans le domaine de l’éducation historique ont tradionnellement mis l’emphase sur la maitrise des connaissances et le déficit flagrant d’une certaine culture historique commune chez les élèves. Les résultats d’examens ministériels et de sondages épisodiques fortement publicisés rappellent au public l’ignorance chronique des jeunes et alimentent une sorte de “guerre de l’histoire” (history wars) concernant la “véritable” matière à enseigner dans les écoles.

Malheureusement, tous ces résultats et ces débats publics nous renseignent peu sur la pensée historique des jeunes, sur leur capacité à appréhender, intégrer, organiser et transformer les réalités historiques par l’intellection humaine sous forme de visions narratives; visions servant à orienter leur vie personnelle dans le temps. C’est que l’expérience scolaire des élèves issue d’un curriculum formel et prescrit laisse souvent croire – tant chez les jeunes que les adultes – que l’histoire peut se réduire à un “tas de choses” qu’on apprend dans un programme scolaire, dans les manuels et les cahiers d’exercices qui incarnent ce qu’est l’histoire.

Les récits historiques comme manifestation de la conscience historique

L’élaboration de récits historiques est plus complexe que la maitrise de connaissances brutes et désincarnées issues de programmes scolaires. En fait, ce serait par le récit que l’apprenant élabore des structures d’explication des réalités passées et présentes qui, de ce fait, deviennent intelligibles, signifiantes et graduellement intériorisées dans sa “conscience historique”.[3] Élaboré par des théoriciens allemands, le concept de conscience historique est encore fort peu connu et utilisé en Amérique du Nord. Mais il s’avère, à mon point de vue, extrêmement utile pour la recherche sur l’apprentissage historique. En effet, la conscience historique va bien au-delà de la maitrise du savoir formel. Car, selon cette approche, les connaissances historiques et les expériences de vie – acquises à la maison, à l’école, dans la communauté et au sein de la culture – sont transformées par l’intellection humaine en véritables histoires personnelles qui donnent sens aux événements, c’est à dire qu’elles donnent une signification particulière à tirer du passé ainsi qu’une direction pour l’avenir.[4] En ce sens, on voit bien que la conscience historique sert à articuler non seulement les dimensions du passé et du présent mais également du passé et de l’avenir permettant à tout individu de s’orienter dans la durée. Pour l’historien allemand Jörn Rüsen, cette conscience historique relève d’une compréhension active et réfléchie des dimensions du temps sous forme narrative qui guide nos actions et nos jugements moraux.[5] Bref, la conscience historique ne peut être réductible à un “tas de choses” issues de la mémoire.

Le savoir historique des jeunes

Si, comme le soutient Paul Ricoeur, le temps devient véritablement “temps humain dans la mesure ou il est articulé de manière narrative”[6] et si ces récits sont bel et bien la manifestation de la conscience historique, il faut donc être plus attentif aux histoires que les jeunes apprennent et nous racontent. Plusieurs études, dont les nôtres, suggèrent que les jeunes développent des récits historiques excessivement simplifiés et réducteurs qui, selon le didacticien Denis Shemilt, sont des “condensés évènementiels” de changements historiques séparés par de longues périodes de silence au cours desquelles rien ne se passe.[7] En fait, les jeunes ont tendance à compresser le temps humain en une série d’événements épisodiques comme si l’histoire ressemblait à un “un volcan qui entre en action lors d’éruptions sporadiques”.[8]

Ces simplifications narratives se développent souvent très tôt dans l’évolution des jeunes et peuvent être extrêmement robustes face au changement car elles servent de schémas pour organiser leurs représentations du passé et d’heuristiques pour structurer l’apprentissage de nouvelles connaissances. On voit bien ici que les récits et les connaissances préalables des jeunes doivent être activées et examinées attentivement si l’on souhaite transformer leurs visions narratives du passé, sans quoi l’éducation risque d’avoir peu d’effet sur la conscience historique des jeunes. En fait, l’étude de Sam Wineburg et de son équipe sur la conscience historique d’adolescents américains démontre qu’en véhiculant une conception strictement curriculaire de l’histoire au sein du système scolaire, les éducateurs et les chercheurs négligent toute une panoplie d’expériences réelles et formatrices provenant de sources sociétales externes à l’école qui affectent sérieusement les représentations historiques des jeunes. Selon eux, ce “curriculum culturel” joue un rôle de premier plan dans l’élaboration des visions historiques des élèves et peut s’avérer “plus puissant que toute une montage de manuels scolaires”.[9]

Complexifier les récits historiques

La plus part des éducateurs canadiens sont au jour des théories dites “constructivistes” et de la nécessité de prendre en compte les connaissances préalables des apprenants. Or, ces derniers sont rarement évalués sur leurs propres représentations narratives du passé collectif. Les éducateurs élaborent plutôt des outils d’analyse diagnostique qui visent à jauger leur niveau de connaissance des objectifs d’apprentissages tirés des programmes d’études. La conséquence est que les jeunes canadiens ne disposent pas de mécanismes au sein du système scolaire leur permettant de raconter et de confronter leurs divers récits historiques acquis au gré d’expériences formatrices provenant du curriculum culturel.

A titre de didacticien, il m’apparaît important, voire nécessaire, de sonder les visions narratives des jeunes qui, trop souvent dans nos sociétés hyper-scolarisées, échappent à la conscience des principaux intéressés, enseignants, élèves, et parents. Précisons que ces visions sont puissantes du fait de leur simplicité et fortement encrés dans leur conscience historique. Dans ces conditions, on comprend pourquoi l’éducation historique doit mieux évaluer, questionner et complexifier les récits que les jeunes apprennent, partagent et utilisent pour s’orienter dans le temps et donner un sens au monde qui les entoure. La classe d’histoire doit devenir un lieu où le curriculum culturel est pris en compte dans l’évaluation des apprenants et le développement de leur conscience historique et citoyenne. Inviter les jeunes à raconter l’histoire de leur société, telle qu’ils la savent, constitue un moyen pratique et efficace de sonder leurs connaissances, leurs visions et leurs représentations signifiantes du passé. En occultant la pensée narrative, on prive les éducateurs d’un des grands modes culturels d’appréhension de la réalité humaine.[10]

____________________

Literature

- Bruner, Jerome, ‘Narrative and paradigmatic modes of thought,’ in Elliot Eisner (ed.), ‘Learning and Teaching the ways of knowing,’ Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1985, p. 97-115.

- Carr, David, ‘Time, narrative and history,’ Indiana: Indiana University Press 1986.

- Ricoeur, Paul, ‘Time and narrative,’ 2 vols, Chicago: Univerity of Chicago Press 1984.

Liens externe

- Centre for the Study of Historical Consciousness. The University of British Columbia: http://www.cshc.ubc.ca (last accessed 30.03.2015).

- Historical Encounters, Journal of historical consciousness, historical culture and history education: http://hej.hermes-history.net (last accessed 30.03.2015).

____________________

[1] L’auteur voudrait remercier le doctorant Raphaël Gani (rgani011@uottawa.ca) pour ses commentaires judicieux sur l’ébauche de cet article.

[2] J. H. Liu, & D. J. Hilton, “How the Past Weighs on the Present: Social Representations of History and Their Role in Identity Politics,” The British Journal of Social Psychology, 44 (2005), 537–556.

[3] W. Grolnick, E. Deci et R. Ryan, “Internalization within the family: The self-determination theory perspective” dans James Wertsch, Voices of collective remembering (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 121.

[4] Voir N. Tutiaux-Guillon & D. Nourrisson (dir.), Identités, mémoires, conscience historique (St-Étienne: Publications de l’Université de St-Étienne, 2003); P. Seixas (dir.), Theorizing historical consciousness (Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2004); J. Rüsen, History: Narration, interpretation, orientation (New York, NY: Berghahn Books, 2005); C. Duquette, “Le rapport entre la pensée historique et la conscience historique: Élaboration d’un modèle d’interaction lors de l’apprentissage de l’histoire chez les élèves de 5e secondaire des écoles francophones du Québec,” thèse de doctorat, Université Laval, 2011; et J. Létourneau, Je me souviens ? Le passé du Québec dans la conscience de sa jeunesse (Montréal, QC: Fides 2014).

[5] Rüsen, History: Narration, interpretation, orientation, 25.

[6] Paul Ricoeur, Temps et récit, vol.1 (Paris : Editions du Seuil, 1983), 17.

[7] Voir B. VanSledright and J. Brophy, “Storytelling, imagination, and fanciful elaboration in children’s historical reconstructions,” American Educational Research Journal, 29 (1992), 837-859; K. Barton, “Narrative simplifications in elementary students’ historical thinking,” dans J. Brophy (dir.), Advances in Research on Teaching, vol. 6 (Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 1996), 51-84; D. Shemilt, “The Caliph’s Coin: The currency of narrative frameworks in history teaching,” dans P. Seixas, P. Stearns, and S. Wineburg (dir.), Knowing and teaching history: National and international perspectives (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2000), 83-101; S. Lévesque, J. Létourneau, and R. Gani. “A Giant with Clay Feet: Québec Students and Their Historical Consciousness of the Nation.” International Journal of Historical Learning, Teaching and Research 11, 2 (2013); M. Robichaud, “L’histoire de l’Acadie telle que racontée par les jeunes francophones du Nouveau-Brunswick : construction et déconstruction d’un récit historique,” Acadiensis 40, 2 (2011): 33-69 ; et J. Létourneau and S. Moisan, “Mémoire et récit de l’aventure historique du Québec chez les jeunes Québécois d’héritage canadien-français: coup de sonde, amorce d’analyse des résultats, questionnement,” Canadian Historical Review 84, 2 (2004): 325-357.

[8] D. Shemilt, History 13-16: Evaluation Study (Edinburgh, UK: Holmes McDougall, 1980), 35.

[9] S. Wineburg, S. Mosborg, D. Porat, et A. Duncan, “Forrest Gump and the future of teaching history,” Phi Delta Kappan (November 2007), 176.

[10] Sur l’importance de la structure narrative et de la narration en histoire, voir B. Hardy, “Narrative as a primary act of mind,” dans M. Meek, A. Warlow, et G. Barton, The Cool Web: The pattern of children’s reading (London, UK: Bodley Hean, 1977), 135-141; P. Ricoeur, Temps et récit, 3 vol. (Paris : Editions du Seuil, 1983-1985); D. Carr, Time, Narrative and History (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986); et J. Bruner, “Narratives and paradigmatic modes of thought,” dans E. Eisner (dir.), Learning and teaching the ways of knowing (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1985), 97-115.

____________________

Crédits Illustration

© Lesekreis. Wikimedia Commons (public Domain).

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ALibrary_Walk_6.JPG

Citation recommandée

Levesque, Stéphane: Quelle est l’importance des récits historiques? Complexifier les histoires que nous racontent les jeunes. In: Public History Weekly 3 (2015) 11, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2015-3819.

Copyright (c) 2015 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact: elise.wintz (at) degruyter.com.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 3 (2015) 11

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2015-3819

Tags: Canada (Kanada), Historical Consciousness (Geschichtsbewußtsein), History Teaching (Geschichtsunterricht), Language: French

Great post’s!

I agree that prior knowledge and possible alternative narratives are exactly the sweet spots for enriched educational encounters.

If readers are interested in a way that historical narratives have and can be pedagogically applicable across the grades (in this case with social studies pre service teachers) we have been doing this here at the University of Alberta for years. See both the method and research results at the literature cited.

References

den Heyer, K., Abbott, L. (2011) Reverberating echoes: Challenging teacher candidates to tell and learn from entwined narrations of Canadian history Curriculum Inquiry, 41 (5), 610-635.

Lucas Garske is Research Fellow at Georg-Eckert-Institut, Braunschweig (Germany).

Stèphane, I´m following your research since you had a presentation at our institute and I love the rich research material that you are generating by giving students the appearently simple task to tell the story of their homeland. I also agree that history education can learn a lot from narrativist approaches and that it should challenge students “own” historical narratives.

I have some considerations with regard to what you write about students typyically compressing the “collective past”: Should we really discuss this as a students issue? Can we claim it is typically compressed (which implicetly means that it can be – even if atypically – uncompressed)? I believe that whatever students do may differ quantitatively, but not qualitativey from what “professional historians” do: they select and exclude. To use Shemilts’ metaphor, students don´t act as if history was like a volcano – it is this volcano. No matter which historical narrative we look at, we will find a highly anachronical structure, full of analepses and prolepses. Of course, we can make students narratives more complex, but I believe that the only reason why we may believe that at some point we turned the volcano into coagulating lava is because it became so complex to us that we are not able to see the hollow spaces and lumps between the particles anymore. Should it be our goal to turn our students into painters of “big pictures”? Maybe. Nonetheless, not everyone’s an artist. At least some should become critics.

Replik

Thank you Lucas for this very thoughtful review of my post and sorry for this long delay. To avoid any confusion here, I agree with you on both counts — that narrative form is imposed not rescued from the past and students’ ideas are no different from adults in many ways.

What I should have said is that students tend to “oversimplify” the past in narrative. They interpret historical changes as though they involved only the actions and intentions of a few individuals rather than societal structures or collective action. Students also think of the past as taking the form of a relatively linear story (generally one of human progress), with a limited number of characters and a clear sequence of events.

These depart significantly from what historians do and think about history in their narrative explanations. While both attempt to generate intelligible “big pictures” of the past, students’ ideas typically lack the sophistication needed to understand the complex, polythetical nature of history – and human experiences.

This is, in my view, what history education should do …