From our “Wilde 13” section.

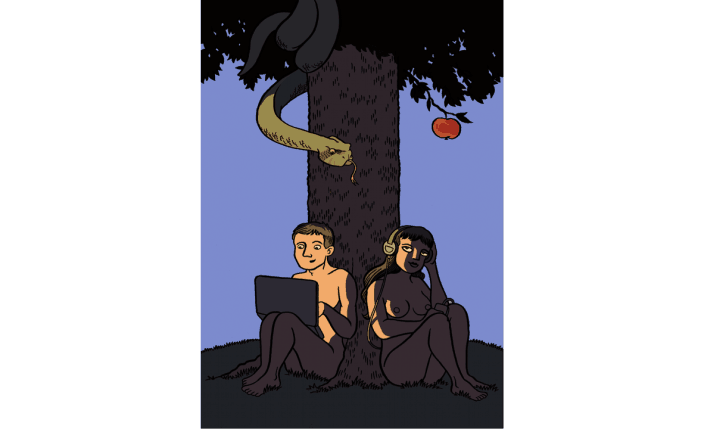

Abstract: Are you still listening to the promises that interconnectedness would abolish all hierarchies, that that mythical entity, “The Web,” would dissolve all boundaries, providing everything for everyone, a promised digital realm within immediate reach? All one had to do, so the claim went, was to be creative yet highly disciplined, and permanently online with everyone else, all of us using the new, smart programmes.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2014-1413.

Languages: English

Are you still listening to the promises that interconnectedness would abolish all hierarchies, that that mythical entity, “The Web,” would dissolve all boundaries, providing everything for everyone, a promised digital realm within immediate reach? All one had to do, so the claim went, was to be creative yet highly disciplined, and permanently online with everyone else, all of us using the new, smart programmes.

“A single liquid fabric of interconnected words and ideas”

This is the sermon of the digital revolution that has been preached for almost thirty years—in manifold forms, persistently couched in the same phrases, no matter whether personal computers or the Web 2.0 are concerned, or indeed science communication. The old information elites were crumbling, a Californian counterculture manifesto proclaimed in 1988: “The kids are at the controls.” 1 The farewell to the private documents of the Gutenberg Galaxy, as Norbert Bolz asserted in 1993, was also a “a farewell to hierarchy, category, and sequence”2; all that counted now were “authorless texts, written while being read.” From the turn of the millenium, weblogs and discussion platforms were welcomed with the same fantasies of redemption. In an article about Google’s new digitisation projects, published in The New York Times in 2006, writer and Internet activist Kevin Kelly was perfectly sure that all texts, past and present, and in all languages, would within a few years be transformed into “a single liquid fabric of interconnected words and ideas” available to everyone, at any time, everywhere.3

Prophecy and Speaking in Tongues

What makes prophecies so readily exchangeable is that they come from the past. They are heavily contaminated with history, above all with religious vocabulary. Cyberspace thereby becomes a self-administered paradise, in which we feel nestled, at long last, in the community of believers. Cyberspace, we know, includes a speaking in tongues. The same is equally true of its gloomy alternatives: a digitally-induced end of the world, caused by stultification and distraction, a sinful flood of images and information overload. It seems far from simple to discuss the possibilities, limits, and constraints of the new channels without resorting to esoteric kitsch and pessimistic penitential sermons. Yet even a cursory glance back reveals that previous technologies were embraced with similar hopes. In 1912, Thomas Alva Edison prophesied that books would become superfluous in the future because films would convey all human knowledge. Alvin Toffler popularised the notion of information overload in 1970, in the age of the golf ball typewriter; a few years earlier, writing about the photocopier, Marshall McLuhan had cheerfully trumpeted that authors were now their own publishers.4

Science Communication, Self-Managed

The photocopier, as a cheap reproduction technology, had brought forth new forms of communication in the sciences between the late 1960s and the early 1980s. Today, these forms are called “grey literature”: informal micro-publications, self-typed and stapled brochures, documentation and manifestoes published in small print runs, from a few dozen to several hundred copies depending on the context and the occasion. Some of these publications became regularly appearing journals and periodicals whereas most, however, were very short-lived. Contemporary historians are familiar with these bodies of material: it is hardly possible to write the history of protest movements (and universities) in the second half of the twentieth century without recourse to these sources. And yet their sheer mention makes university archivists knit their brows: produced on cheap material, designed for ready use, these collections present documentalists with a highly practical problem: disintegration. “Grey literature,” with its unruly diversity, its ultra-small print runs, and its relentless transformation, was not only a medium of communication but also one of disappearance. In the age of blogs, discussion platforms, and social media, this sounds familiar. Curiously, “grey literature” remains unmentioned in discussions on the future of scientific publishing, even though it was intimately related both to the communities of prosumers, who were authors and readers at one and the same time, and to serious scientific articles and books. The message for those seeking the immediate precursors of the digital channels in the sciences, with their topical, informal, and tentative references: here they are.

A Revolution Gone Grey

The lesson learned? Well, the new media provide no redemption, nor do they spell the end of the world. Fast digital transmission channels, and their constant refinement, do not abolish their slow, analog, paper-bound precursors. Never before have printed articles and books been as necessary as today, as filters for attaining stable outcomes: highly frequented “hot” media of digital communication—such as this one—support and promote “cooler” storage, which ensures longer storability and shelf life. Hence constant reference to print publications is made in digital formats. The same can be said of online scientific publications, as of every usable Wikipedia entry. And really good blogs become—books. Hello, digital revolution: is there anyone out there? Only collected volumes, as we all know, are read by no one. And yet they continue to multiply.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Groebner, Valentin. Wissenschaftssprache digital: Die Zukunft von gestern (Constance: Constance University Press, 2014) [forthcoming].

- idem. “Nach der Megabit-Bombe,” Mittelweg 36 22 (2013) 4, pp. 29-37.

- idem. Wissenschaftssprache: Eine Gebrauchsanweisung (Constance: Constance University Press, 2012).

Web Resources

- “Muss ich das lesen?” FAZ online, 10.2.2013 (last retrieved 21.1.14).

- Video recording of a lecture delivered by Valentin Groebner at the RKB Conference (Munich, January 2013) (last retrieved 21.1.14).

_____________________

Image Credits

© Andreas Kiener (http://andreaskiener.ch) 2013, with the kind support of Data Quest AG (http://www.dataquest.ch)

Recommended Citation

Groebner, Valentin: Hot Property, Cool Storage, Grey Literature. In: Public History Weekly 2 (2014) 6, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2014-1413.

Translation (from German)

by Kyburz&Peck, English Language Projects (www.englishprojects.ch)

Copyright (c) 2014 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

- Quoted from Fred Turner, From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network and the Rise of Digital Utopianism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), p. 164. ↩

- Norbert Bolz, Am Ende der Gutenberg-Galaxis: Die neuen Kommunikationsverhältnisse (Munich: Fink, 1993), pp. 217 and 223. ↩

- Kevin Kelly, “Correction Appended,” New York Times, 14 May 2006. ↩

- Claus Pias, “Eine kurze Geschichte der Unterrichtsmaschinen,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 4 December 2013, p. N5; Alvin Toffler, The Future Shock (New York: Bantam Books, 1970); Monika Dommann, Autoren und Apparate: Copyright im Medienwandel (Frankfurt/M.: Fischer, 2014), p. 249 ff. ↩

Categories: 2 (2014) 6

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2014-1413

Tags: Digital Change (Digitaler Wandel), Science Communication (Wissenschaftskommunikation), Wilde13

Anything goes

While I appreciate Groebner Valentin’s framing of digital publication as grey literature, I’m afraid that this brief essay repeats yet again the false binary of digital vs. analog scholarship as though we are somehow forced to chose one or the other. More useful, to my mind, is the notion that “scholarship” is a much more inclusive notion, one that takes in various forms of publication ranging from the shortest of all, i.e., the carefully considered tweet on a pressing issue facing researchers, to longer versions, i.e., the 300-400 word research note written by a biologist working in the field, or a blog post that grapples with an important disciplinary issue, such as an article in a journal or a book. Each of these forms of scholarly engagement takes place in the same medium — text — and each is subject to a form of peer review, whether pre- or post-publication. And each asks others, whether in the general public or in the scientific community (or both simultaneously) to engage with the ideas, analysis, new data, or polemics of the researcher.

What matters is not the form, but the result. As scholars, we are expected to find new data, analyze what we’ve found, and then circulate our findings to a larger community of peers and the wider public. How we choose to do that, it seems to me, matters much less than the impact of our work. Does a new finding, or a new way of looking at previously known information change perceptions of a historical moment, an endangered species, or the motion of charged particles? If the answer is yes, then it matters not that the finding appeared first in a blog, at a conference, in a scientific paper, or in a book published by a well-established academic press. Circulation of knowledge and the impact of that knowledge is what matters.

Thus, I am troubled by Valentin’s dismissal of grey literature, whether digital or analog. If, as he asserts, the collection of essays is read by almost no one, what are we to make of my own blog on historical pedagogy that has had over 1.5 million page views since 2007? Or of a digital historical project I created on the revolutions of 1989 that since 2007 has had more than 1.3 million page views? If our goal is the circulation of knowledge, then I would assert that these “grey” publications of mine have circulated much farther and much wider than any book on either subject.

Anm. der Redaktion

T. Mills Kelly’s Weblog: Edwired. Teaching History in the Digital Age

Anything goes, but who gets to join in?

Thank you to both Valentin Groebner and Mills Kelly for a thought-provoking discussion. Mills Kelly’s emphasis is on impact – how we choose to circulate our findings matters less than that we do so effectively. A good point, and well made. But that particular argument is concerned with dissemination as the final stage in a long process of scholarly enquiry. What are the implications of working in an environment in which the new media play a powerful role (however we conceive of how they relate to, coexist with or complement ‘analogue’ scholarship) for the process of scholarship itself? Crowd-sourcing of data and pattern-identification isn’t that new in the sciences, and in the humanities, projects such as Trove in Australia are drawing in thousands of users to correct texts, tag items, upload content and contribute to the interpretation of material.

Nonetheless, old hierarchies, as Valentin Groebner notes – the book, the journal article – persist. Crowd-sourcing doesn’t change where the ‘real business’ of scholarship happens; it out-sources some of the graft involved to volunteer research assistants in cyberspace. Crowd-sourcing is valuable; it undoubtedly has an impact on research and on the circulation of knowledge. But does it fundamentally transform the process of knowledge creation? Mills Kelly is undertaking some impressive, and impressively radical, work with his students that is enabling them to move into the space of making and re-making history. Can we extend this from the classroom and into our core work, and identity, as historians – without that implying a compromise in intellectual rigour?

Public history talks the language of co-production of knowledge (and co-curation in museums is an emerging concept) and, in certain forms, the involvement of people as the subjects and audiences of historican enquiry is taken seriously. I think we can be more ambitious, however. There are some excellent public history platforms out there; the Old Bailey Online is a pioneering example, and even relatively simple platforms such as WordPress and HistoryPin are allowing students, community groups, heritage organisations and many others to contribute to historical knowledge. But what is the next stage? How can the scholarly conversation be opened up – as opposed to just scholarly knowledge? How can both ‘new’ and ‘old’ media, and the blurring of the boundaries between them, help create a much broader community of enquiry, not just a wider audience?

Anm. der Redaktion

Alix Greens Weblog: thehistoricalimperative. History, policy, higher education and public life