Abstract: Today, public history is a global discipline, which considers the presence of the past—and the construction of history—outside academic settings. The practice of history has always been “public” in a way, but individual and collective memories are now invading the public sphere. Conflicting perceptions of the past, and the inability to forget, require professional mediation. Public historians answer the increasing demand for history worldwide and interpret the past with and for the public. Awareness of their global role fosters the internationalizing of public history.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2014-2647.

Languages: English, Deutsch, Français

Today, public history is a global discipline, which considers the presence of the past—and the construction of history—outside academic settings. The practice of history has always been “public” in a way, but individual and collective memories are now invading the public sphere. Conflicting perceptions of the past, and the inability to forget, require professional mediation. Public historians answer the increasing demand for history worldwide and interpret the past with and for the public. Awareness of their global role fosters the internationalizing of public history.

Everybody’s interpreting their own past

During the last thirty years, not only Anglo-Saxon historians have engaged in public discussions about the past. Especially public historians have been interested in collecting and interpreting memories using oral history and digital technologies. Through social media and the worldwide web, conflicting collective memories of genocidal pasts, dictatorships, and violent civil wars, have been displayed in virtual and physical museums to ensure better public understanding of such history.[1] Truth and reconciliation commissions and remembrance portals, such as the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, have interacted with local communities involving public historians to recover forgotten and uncomfortable civil memories. Even before the initiation of a participatory 2.0 Web, which allows individuals and communities to crowd-source their own vision of history, nonacademic publics were eager to rememorize their families and local histories.[2] People also knew about history from visiting monuments and battlefield parks, from true “Lieux de Mémoire,” and from exploring thematic museums and exhibitions offering popular narratives about nearby pasts. Thus, professional public historians, especially within the digital realm, are confronted with everybody’s public pasts.[3] Historical expertise is needed for acquiring deeper contextualized understandings of history. Working within communities and for the public, public historians are the answer to such an universal interest in the past. Their task is to publicly communicate history.

Different approaches to public history

International public history uses specific professional skills to understand divergent historical approaches to the discipline. Forty years after its institutionalization as a university discipline in California, public history has since spread to other countries. So what makes history public, and what makes public history, become a constantly expanding and self-confident discipline? In September 2014, a 2nd Simpósio Internacional de História Pública was held in Niterói (Rio de Janeiro) in Brazil: “Perspectivas da História Pública no Brasil.” The Rede Brasileira de História Pública showcased different facets of Brazilian public history (multi-ethnic, social, political, and local public history practices) in workshops and participatory media ateliers.[4] But why did the Rede, a federal decentralized network of historians belonging to different universities, use the term “international” for a conference about Brazilian public history? Universal practices and theoretical reflections on the impact of digital history and on the presence of oral history in Brazil were discussed at roundtables and officinas by national and some international scholars. Linda Shopes, a pioneer of American oral history, focused on the close integration of oral and public history. She discussed the concept of “shared authority” (Frisch 1990)[5], introduced into the debate by Raphael Samuel during the 1970s in Oxford.[6]

Glocal public history is surrounding us

Different ideas about what history is about have emerged in various societies and follow different patterns across the world. Nevertheless, public history often remains a discipline without, however, bearing that name. Historians entering the public arena and creating narratives through the media have not always been aware of the existence of a discipline called “Public History.” Academic historians have the tendency to call public history what is, de facto, a “public use of history,” by engaging with the discipline, its skills and practices, within contemporary debates about the past in the polis.[7] Only recently, and caused by the digital turn in history and its profound impact on public history practices, have new forms of awareness and an overwhelming necessity of the field arisen. These phenomena have occurred globally despite the universal ambiguities and contradictions about a common definition of the field. Its internationalization is underway worldwide and resembles a multi-faceted process of globalization. This shift also derives from the crisis of academic history in our post-colonial societies. Emblematic of this process was the creation of the International Federation for Public History (IFPH). In 2010, the International Federation for Public History was established as a internal committee of the Comité International des Sciences Historiques-International Committee for the Historical Sciences. Today, the IFPH is mandated to bring together international public historians, to promote the development of a growing worldwide network of practitioners, and to foster national public history programs and associations.

Asking for a global public role?

This question addresses the “glocal” need for public history. Our world is glocal. Europe has long lost its central role in defining a universal idea of the past through its Eurocentric narrative and its colonial and post-colonial history. Subaltern Studies have meanwhile theorized what has already long been evident: local pasts have emerged everywhere and have formed multi-centered globalized pasts.[8] This decentralization of history has fostered the field worldwide and favored the birth of a glocal history.[9] Public history has often meant working on the past with local communities and for a better understanding of their local-global memories. This process is all about establishing a common definition of international public history using oral interviews, remembering individual and collective memories, collecting and preserving sources, creating museums and exhibitions, and confronting difficult pasts and their interpretation. The usefulness of international public history relies on the universality of these glocal practices.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Serge Noiret, “La digital history: histoire et mémoire à la portée de tous,” in Pierre Mounier (ed.), Read/Write Book 2: Une introduction aux humanités numériques (Marseille: OpenEdition, 2012), pp. 151–177, online: http://press.openedition.org/258 (last accessed 06.10.2014).

- James B. Gardner, Peter S. LaPaglia (eds.), “Public history: essays from the field,” (Malabar, Florida: Krieger Pub. Co., 2nd edition, 2006).

- Guy Zelis (ed.), “L’historien dans l’espace public: l’histoire face à la mémoire, à la justice et au politique,” (Loverval: Labor, 2005).

Web Resources

- Public History Commons, International section: http://publichistorycommons.org/international/ (last accessed 06.10.2014).

- International Federation for Public History: http://ifph.hypotheses.org. (last accessed 06.10.2014).

- Rede Brasileira de Historia Publica: http://historiapublica.com.br/ (last accessed 06.10.2014).

____________________

[1] Silke Arnold-de Simine: Mediating memory in the museum: trauma, empathy, nostalgia., Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013; Wolfgang Muchitsch: Does war belong in museums? The representation of violence in exhibitions., Bielefeld: Transcript, 2013.

[2] Paula Hamilton and Linda Shopes (eds.): Oral History And Public Memories., Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2008.

[3] Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen. The Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life. Columbia University Press, 1998; Paul Ashton and Paula Hamilton: History At The Crossroad: Australians and The Past., Ultimo: Halstead Press, 2010; Margaret Conrad, Jocelyn Létourneau and David Northrup: “Canadians and their Pasts: An Exploration in Historical Consciousness,” in The Public Historian, vol.31, n.1, February 2009, pp.15-34.

[4] Juniele Rabêlo de Almeida and Marta Gouveia de Oliveira Rovai (eds.) Introdução à história pública. São Paulo: Letra e Voz, 2011.

[5] Michael Frisch: A Shared Authority: Essays On The Craft And Meaning Of Oral And Public History, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990.

[6] Raphael Samuel: Past and present in contemporary culture, London: Verso, 1994.

[7] François Hartog and Jacques Revel: Les usages politiques du passé., Paris : Ecole des hautes études en sciences sociales, 2001; Giorgos Antoniou (ed.): History and the Public Sphere in Contemporary Greece in Ricerche Storiche, XLIV/1, January-April 2014, http://www.polistampa.com/asp/sl.asp?id=6222 (last acess 06.10.2014).

[8] Dipesh Chakrabarty: Provincializing Europe: postcolonial thought and historical difference, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

[9] Robert Weyeneth: “Writing Locally, Thinking Globally”, in Public History News, vol.33, n.1, December 2012, p.8.

_____________________

Image Credits

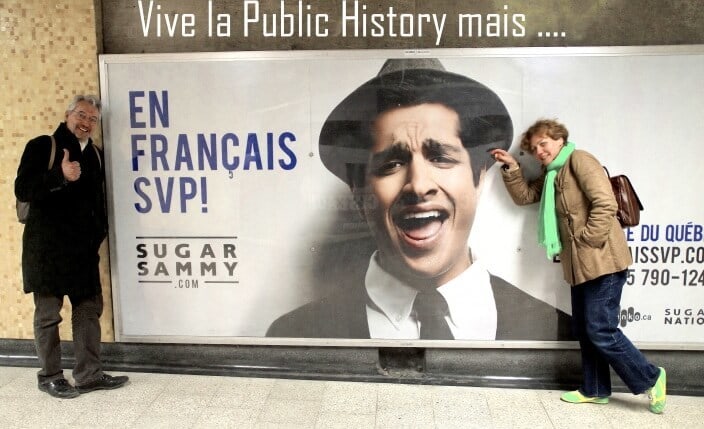

© Serge Noiret, 2013. Public Historians in Montreal before the NCPH-IFPH international conference in Ottawa.

Recommended Citation

Noiret, Serge: Internationalizing Public History. In: Public History Weekly 2 (2014) 34, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2014-2647.

Die Public History hat sich zu einer weltweit tätigen Disziplin entwickelt, die sich mit der Gegenwärtigkeit der Vergangenheit – und mit dem Konstruktionscharakter von Geschichte – außerhalb akademischer Gegebenheiten auseinandersetzt. In gewisser Weise war die Praxis der Geschichtsschreibung schon immer “öffentlich”, doch individuelle und kollektive Erinnerung sind heutzutage in der öffentlichen Sphäre allgegenwärtig. Konkurrierende Vorstellungen von der Vergangenheit und die Unfähigkeit, zu vergessen, erfordern professionelle Vermittlung. Public Historians geben Antwort auf die steigende weltweite Nachfrage von Geschichte und interpretieren die Vergangenheit für die Öffentlichkeit. Das Bewusstsein über ihre globale Bedeutung treibt den Internationalisierungsprozess der Public-History-Idee immer weiter an.

Jeder macht sich ein eigenes Bild von der Vergangenheit

Während der letzten 30 Jahre waren HistorikerInnen nicht nur im angelsächsischen Raum in öffentliche Diskussionen über die Vergangenheit verwickelt. Besonders VertreterInnen der Public History interessierten sich für das Sammeln von Erinnerungen durch Oral History und durch den Gebrauch digitaler Technologien. Dank Social Media und Web-Veröffentlichungen wurden konkurrierende kollektive Erinnerungen, zum Beispiel über Genozide, Diktaturen, Bürgerkriege, in physischen und virtuellen Museen und Ausstellungen sichtbar gemacht und führten zu einem besseren Verständnis der Konflikthaftigkeit in der Öffentlichkeit.[1] Wahrheits- und Aussöhnungskommissionen sowie Erinnerungsportale, wie beispielweise die International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, traten mit lokalen Gemeinschaften in einen Austausch, indem VertreterInnen der Public History vergessene oder unbequeme Erinnerungen bargen. Bereits bevor der Start des partizipativen Webs 2.0 es Personen und Gemeinschaften ermöglichte, ihre Version der Geschichte zu verbreiten, waren nichtakademische Personen darauf aus, ihre Familien- oder Lokalgeschichte zu erforschen.[2] Die geschichtsinteressierte Öffentlichkeit besuchte Denkmäler und Schlachtfelder, wahrhafte “Erinnerungsorte” (Lieux de Mémoire). Thematische Museen und Ausstellungen, die populäre Narrative über jene Vergangenheit präsentieren, die den BesucherInnen nahe ist und sie berührt.[3] Professionelle VertreterInnen der Public History, vor allem im digitalen Bereich, sahen sich folglich mit jedermanns Vorstellung der Vergangenheit konfrontiert. Historische Expertise wird benötigt, um die Erforschung der Vergangenheit besser zu kontextualisieren und ein besseres Verständnis von Geschichte herbeizuführen. Innerhalb von Gemeinschaften und für die Öffentlichkeit beantworten die VertreterInnen der Public History das universelle Interesse an der Vergangenheit. Ihre Aufgabe ist es, Vergangenheit öffentlichkeitswirksam zu kommunizieren.

Verschiedene Entwicklungswege der Public History

Will man die internationale Public History verstehen, muss man die unterschiedlichen Bedingungen ergründen, unter denen sie sich entwickelt hat. Vierzig Jahre nach ihrer Institutionalisierung als universitäre Disziplin in Kalifornien breitete sich die Public-History-Bewegung auch auf andere Länder aus. Aber was verhilft der Public History dazu, zu einer stetig wachsenden und selbstbewussten Disziplin zu werden? Im September 2014 wurde in Niterói (Rio de Janeiro) in Brasilien das zweite “Simpósio Internacional de História Pública” abgehalten unter dem Titel: “Perspectivas da História Pública no Brasil.” Die “Rede Brasileira de História Pública” zeigte in Workshops und partizipativen Medien-Ateliers verschiedene Facetten der brasilianischen Public History (Multiethnizität sowie verschiedene soziale, politische und lokale Praktiken der Public History).[4] Aber warum nutzte die “Rede” ein föderales dezentrales Netzwerk von HistorikerInnen verschiedener Universitäten, den Begriff “international” für eine Konferenz über brasilianische Public History? Universelle Praktiken und theoretische Reflexionen über die Einflüsse der digitalen Geschichtsschreibung und der Präsenz der Oral History in Brasilien sorgten in Diskussionsrunden und Workshops für Gesprächsstoff, die durch einige internationale WissenschaftlerInnen bereichert wurden. Die Pionierin der amerikanischen Public History, Linda Shopes, hob die enge Bindung von Oral und Public History hervor. Sie diskutierte das Konzept der “geteilten Autorität” (Frisch 1990)[5], das von Raphael Samuel in den siebziger Jahren an der Universität Oxford entwickelt wurde.[6]

Wir sind umgeben von einer glokalen Public History

Verschiedene Vorstellungen darüber, was Geschichte ist, haben sich unterschiedlich entwickelt und folgen weltweit anderen Mustern. Ungeachtet dessen zeigt sich Public History oft als eine Disziplin, die nicht als solche bezeichnet wird. Fachwissenschaftliche HistorikerInnen haben oftmals die Öffentlichkeit gesucht und in den Medien eigene Narrative präsentiert, ohne sich darüber im Klaren zu sein, dass es eine Disziplin namens Public History gibt. Fachwissenschaftliche Historiker neigen dazu, das als Public History zu bezeichnen, was de facto ein “öffentlicher Gebrauch von Geschichte” ist, bei dem die Disziplin, ihre Fertigkeiten und Praktiken in zeitgenössischen politischen Debatten über die Vergangenheit in Anspruch genommen werden.[7] Erst seit wenigen Jahren, begünstigt durch den digitalen Wandel in den Geschichtswissenschaften, der einen enormen Einfluss auf die Praktiken der Public History hatte, hat sich neuerlich ein Bewusstsein für die Disziplin und ein überwältigender Bedarf an ihren Angeboten entwickelt. Dieses Phänomen ereignete sich gleichermaßen auf der ganzen Welt. Dessen ungeachtet bleiben die Widersprüche und Mehrdeutigkeiten beim Versuch einer allgemeingültigen Definition der Public History bestehen. Der Internationalisierungsprozess vollzog sich derweil weltweit und folgt dem multifaktoriellen Prozess der Globalisierung. Symbolisch für diesen Prozess war die Bildung der “International Federation for Public History.” Im Jahre 2010 wurde die “International Federation for Public History” gegründet als interner Arbeitskreis des Comité International des Sciences Historiques-International Committee for the Historical Sciences. Heute ist die IFPH damit beschäftigt, internationale Verbindungen zwischen den VertreterInnen der Public History auf der ganzen Welt herzustellen, die Entwicklung eines weltweiten Netzwerks zwischen PraktikerInnen voranzutreiben sowie die nationalen Public-History-Programme und -Verbände zu fördern.

Bedarf an einer globalen öffentlichen Rolle?

Die Antwort auf diese Frage zeigt den „glokalen“ Bedarf an Public-History-Forschung. Unsere Welt ist „glokal“. Längst hat Europa seine zentrale Rolle in der Definition einer universellen Idee von Vergangenheit durch das europäische Narrativ verloren, in dem stets seine koloniale und post-koloniale Geschichte erzählt wurde. Die “Subaltern Studies” beschreiben in der Theorie, was bereits offen ersichtlich ist: Überall haben sich die lokalen Vergangenheiten globalisiert und die Multikulturalität eine globalen Geschichte bestätigt.[8] Diese Dezentralisierung der Geschichte hat die Disziplin der Public History in der ganzen Welt befördert und zugleich einen Bereich der Public History hervorgebracht, den man als “glokale” Dimension bezeichnen könnte.[9] Public History bedeutet die Aufarbeitung der Vergangenheit von lokalen Gemeinschaften, um diese besser in ihre lokal-globale Erinnerung einzuordnen. Der Prozess, mit dem die internationale Public History dies aufarbeitet, ist weltweit der gleiche: Führung von Interviews, Aufarbeitung einer individuellen und kollektiven Erinnerung, Sammeln und Bewahren von Quellen, Erstellung von Museen und Ausstellungen, die sich den schwierigen Bereichen der Vergangenheit und ihrer Interpretation stellen. Der Nutzen der internationalen Public History liegt somit in der Universalität dieser “glokalen” Praktiken.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Noiret, Serge: La digital history. histoire et mémoire à la portée de tous. In: Mounier, Pierre (Hrsg.): Read/Write Book 2. Une introduction aux humanités numériques. Marseille 2012, S. 151-177. Online verfügbar: http://press.openedition.org/258 (zuletzt am 06.10.2014).

- James B. Gardner / Peter S. LaPaglia (Hrsg.): Public history: essays from the field. 2. Aufl. Malabar/Florida 2006.

- Zelis, Guy (Hrsg.): L’historien dans l’espace public: l’histoire face à la mémoire, à la justice et au politique. Loverval 2005.

Webressourcen

- Public History Commons, International section: http://publichistorycommons.org/international/ (zuletzt am 06.10.2014).

- International Federation for Public History: http://ifph.hypotheses.org. (zuletzt am 06.10.2014).

- Rede Brasileira de Historia Publica: http://historiapublica.com.br/ (zuletzt am 06.10.2014).

____________________

[1] Silke Arnold-de Simine: Mediating memory in the museum: trauma, empathy, nostalgia. Basingstoke 2013; Wolfgang Muchitsch: Does war belong in museums? The representation of violence in exhibitions. Bielefeld 2013.

[2] Paula Hamilton and Linda Shopes (eds.): Oral History And Public Memories. Philadelphia 2008.

[3] Roy Rosenzweig / David Thelen. The Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life. Columbia 1998; Paul Ashton / Paula Hamilton: History At The Crossroad: Australians and The Past. Ultimo 2010; Margaret Conrad / Jocelyn Létourneau / David Northrup: Canadians and their Pasts: An Exploration in Historical Consciousness. In: The Public Historian, vol.31, n.1, February 2009, S.15-34.

[4] Juniele Rabêlo de Almeida and Marta Gouveia de Oliveira Rovai (eds.) Introdução à história pública. São Paulo 2011.

[5] Michael Frisch: A Shared Authority: Essays On The Craft And Meaning Of Oral And Public History. Albany 1990.

[6] Raphael Samuel: Past and present in contemporary culture. London 1994.

[7] François Hartog and Jacques Revel: Les usages politiques du passé. Paris 2001; Giorgos Antoniou (Hrsg.): History and the Public Sphere in Contemporary Greece in Ricerche Storiche, XLIV/1, January-April 2014, http://www.polistampa.com/asp/sl.asp?id=6222 (zuletzt am 06.10.2014).

[8] Dipesh Chakrabarty: Provincializing Europe: postcolonial thought and historical difference. Princeton 2000.

[9] Robert Weyeneth: Writing Locally, Thinking Globally. In: Public History News, Ausg. 33, Nr.1, December 2012, S.8.

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

© Serge Noiret, 2013. Public History ForscherInnen in Montreal vor der internationalen NCPH-IFPH Konferenz in Ottawa.

Übersetzung aus dem Englischen

von Marco Zerwas

Übersetzung aus dem Englischen

Noiret, Serge: Internationalisierung der Public History. In: Public History Weekly 2 (2014) 34, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2014-2647.

L’Histoire publique est aujourd’hui une discipline planétaire qui considère la présence du passé -et l’histoire- en dehors des milieux universitaires. La pratique de l’histoire a toujours été «publique» d’une certaine manière, mais les mémoires individuelles et collectives envahissent la sphère publique. Des perceptions contradictoires à propos du passé et une incapacité à oublier, exigent des médiations professionnelles. Les historiens publics répondent à cette demande croissante d’histoire partout dans le monde et interprètent le passé en public. Conscients de leur rôle, ils favorisent aujourd’hui le processus d’internationalisation de la discipline.

Tout le monde interprète son propre passé

Au cours des trente dernières années -et pas seulement dans les pays anglo-saxons-, les historiens se sont engagés dans des discussions publiques sur le passé. En particuliers, les historiens publics ont récolté la mémoire, souvent sans contexte, en utilisant l’histoire orale et les technologies du numérique. Grâce aux médias sociaux et au web, des mémoires collectives contradictoires comme celles qui touchent aux passés génocidaires, aux dictatures, aux guerres civiles et aux conflits violents, ont été montrés dans les musées virtuels et physiques pour en favoriser une meilleure compréhension publique.[1] Des Comissions de vérité et de réconciliation et des portails commémoratifs comme celui de la Coalition internationale des sites de conscience, interagissent avec les communautés locales utilisant des historiens publics pour retrouver des mémoires civiles oubliées et/ou souvent difficiles à manier. Avant même le début d’un web participatif 2.0 permettant aux individus et aux communautés de fournir publiquement leur propre vision de l’histoire, tout le monde avait été impatient de retrouver et de rendre public ses mémoires familiales et l’histoire locale.[2] Le grand public passionné d’histoire et de mémoire, visite les parcs historiques et les champs de bataille, véritables «lieux de mémoire », comme les musées thématiques et les expositions qui offrent des récits populaires et une évocation du passé qui leur est proche et qui touche directement.[3] Des historiens publics professionnels, en particuliers dans le domaine du numérique, sont confrontés à ces passés rendus publics par quiconque. Une expertise historique est nécessaire dans le monde entiers pour acquérir une compréhension plus profonde de l’histoire, la science du contexte. Travaillant au sein des communautés et pour le public, les historiens publics sont en fait la réponse à une telle requête universelle pour le passé. Leur tâche est de communiquer publiquement l’histoire.

Les différents chemins de l’histoire publique

L’histoire international publique vise à comprendre les chemins divergents qui ont permis d’établir la discipline et les compétences professionnelles spécifiques nécessaires pour la pratiquer. Quarante ans après son institutionnalisation comme discipline universitaire en Californie, l’histoire publique a conquis de nouveaux pays. Donc qu’est-ce qui rend l’histoire, publique, et, surtout, l’histoire publique toujours plus consciente d’elle-même aujourd’hui? Cette année au Brésil, lors du 2ème Simpósio Internacional de Historia Pública, intitulé Perspectivas da História Pública no Brasil, la Rede Brasileira de História Pública a présenté une variété de pratiques multi-raciales, sociales, politiques et locales en histoire publique. Les historiens brésiliens ont conçus des ateliers participatifs sur les médias et ont analysé les différentes facettes de l’histoire publique brésilienne.[4] Mais pourquoi la Rede, un réseau décentralisé et fédéral d’historiens appartenant à différentes universités, a utilisé le terme «international» pour qualifier une conférence sur l’histoire publique brésilienne? Des tables rondes et des officinas -séminaires pratiques- ont favorisé des réflexions théoriques universelles dans le domaine de l’histoire publique et se sont intéressés à l’impact de l’histoire numérique et à la présence de l’histoire orale au Brésil avec, aussi, la participation de spécialistes internationaux. Une pionnière de l’histoire orale américaine, Linda Shopes, a axé son intervention inaugurale, sur l’intégration étroite entre l’histoire orale et publique. Elle a discuté la notion d’«autorité partagée» (Frisch 1990)[5] inaugurée par Raphael Samuel au cours des années soixante-dix à Oxford.[6]

L’histoire publique qui nous entoure

Des idées différentes sur ce que l’histoire est socialement, ont évolué différemment et suivant différents modèles à l’échelle mondiale. Néanmoins, l’histoire publique reste souvent une discipline sans le nom. Les historiens qui entrent dans l’arène publique et les historiens auteurs de récits dans les médias, ne sont pas toujours au courant de l’existence d’un sous-champ ou, plutôt, d’une discipline appelée histoire publique. Les historiens universitaires ont tendance à appeler l’histoire publique ce qui est, de facto, un “usage public de l’histoire“, engageant la discipline, ses compétences et ses pratiques dans des débats contemporains sur le passé de la cité instrumentalisé par la politique.[7] Seulement depuis quelques années maintenant, et favorisé par la révolution du numérique en histoire qui a eu un impact énorme sur les pratiques de l’histoire publique, une nouvelle prise de conscience de l’existence de la discipline et de la nécessité impérieuse du champ s’est affirmée. Ce phénomène s’est produit à l’échelle mondiale. Néanmoins, une définition universelle du domaine de l’histoire publique reste ambigue et contradictoire. Le processus d’internationalisation de l’histoire publique suit ce développement mondial qui s’effectue sur des bases différentes et en fonction des phénomènes de globalisation. Il découle également de la crise générale de l’histoire académique dans nos sociétés postcoloniales. La création de la Fédération internationale pour l’histoire publique est de ce fait emblématique de ce processus de globalisation. Un groupe de travail sur l’histoire publique internationale organisé par le National Council for Public History américain (NCPH) s’est transformé en 2010, en une commission interne permanente du Comité International des Sciences Historiques. Aujourd’hui, la FIHP a pour mandat de créer des liens internationaux entre les historiens publics et de promouvoir le développement d’un réseau mondial de la discipline qui compte de plus en plus de praticiens, outre favoriser la création de programmes universitaires nationaux d’histoire publique et d’associations nationales de la discipline.

A la demande d’un rôle public international?

Répondre à cette question rend compte glocalement et, de ce fait, internationalement, du rôle des historiens publics. Notre monde est maintenant glocal. L’Europe a perdu son rôle central dans la définition d’une idée universelle du passé qui découlait d’un récit euro centrique, de son histoire coloniale et postcoloniale. Les subaltern studies ont théorisé ce qui était déjà évident publiquement: partout, les passés locaux se sont mondialisés et un pluri-centrisme de l’histoire mondiale s’est affirmé.[8] Cette décentralisation de l’histoire a favorisé le domaine de l’histoire publique dans le monde entier, outre la naissance de ce qu’on pourrait appeler la dimension glocale de la discipline de l’histoire publique.[9] L’histoire publique signifie travailler sur le passé avec les communautés locales et, en général, pour une meilleure compréhension de leurs passés locaux/globaux. Le processus en lui-même est exactement ce qu’on peut appeler une histoire publique internationale interprétée globalement et de la même manière partout grâce aux pratiques professionnelles comme les entretiens oraux qui récoltent les mémoires individuelles et collectives, la collecte et la préservation des sources, la création de musées et d’expositions qui se confrontent avec des passés difficiles et avec leur interprétation. L’utilité de l’histoire publique internationale repose ainsi sur l’universalité de ces pratiques glocales.

_____________________

Literature

- Serge Noiret, “La digital history: histoire et mémoire à la portée de tous,” in Pierre Mounier (ed.), Read/Write Book 2: Une introduction aux humanités numériques (Marseille: OpenEdition, 2012), pp. 151–177, online: http://press.openedition.org/258 (dernier accès le 6 Octobre 2014).

- James B. Gardner, Peter S. LaPaglia (eds.), “Public history: essays from the field,” (Malabar, Florida: Krieger Pub. Co., 2nd edition, 2006).

- Guy Zelis (ed.), “L’historien dans l’espace public: l’histoire face à la mémoire, à la justice et au politique,” (Loverval: Labor, 2005).

Liens externe

- Public History Commons, International section: http://publichistorycommons.org/international/ (dernier accès le 6 Octobre 2014).

- International Federation for Public History: http://ifph.hypotheses.org. (dernier accès le 6 Octobre 2014).

- Rede Brasileira de Historia Publica: http://historiapublica.com.br/ (dernier accès le 6 Octobre 2014).

____________________

[1] Silke Arnold-de Simine: Mediating memory in the museum: trauma, empathy, nostalgia., Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013; Wolfgang Muchitsch: Does war belong in museums? The representation of violence in exhibitions., Bielefeld: Transcript, 2013.

[2] Paula Hamilton and Linda Shopes (eds.): Oral History And Public Memories., Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2008.

[3] Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen. The Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life. Columbia University Press, 1998; Paul Ashton and Paula Hamilton: History At The Crossroad: Australians and The Past., Ultimo: Halstead Press, 2010; Margaret Conrad, Jocelyn Létourneau and David Northrup: “Canadians and their Pasts: An Exploration in Historical Consciousness,” in The Public Historian, vol.31, n.1, February 2009, pp.15-34.

[4] Juniele Rabêlo de Almeida and Marta Gouveia de Oliveira Rovai (eds.) Introdução à história pública. São Paulo: Letra e Voz, 2011.

[5] Michael Frisch: A Shared Authority: Essays On The Craft And Meaning Of Oral And Public History., Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990.

[6] Raphael Samuel: Past and present in contemporary culture., London: Verso, 1994.

[7] François Hartog and Jacques Revel: Les usages politiques du passé., Paris : Ecole des hautes études en sciences sociales, 2001 ; Giorgos Antoniou (ed.): History and the Public Sphere in Contemporary Greece in Ricerche Storiche, XLIV/1, January-April 2014, http://www.polistampa.com/asp/sl.asp?id=6222 (last acess 06.10.2014).

[8] Dipesh Chakrabarty: Provincializing Europe: postcolonial thought and historical difference., Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

[9] Robert Weyeneth: “Writing Locally, Thinking Globally”, in Public History News, vol.33, n.1, December 2012, p.8.

____________________

Crédits illustration

© Serge Noiret, 2013. Les historiens publiques à Montréal avant la conférence internationale NCPH–IFPH à Ottawa.

Citation recommandée

Noiret, Serge: L’internationalisation de’l Histoire Publique. In: Public History Weekly 2 (2014) 34, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2014-2647.

Copyright (c) 2014 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 2 (2014) 34

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2014-2647

Tags: Academia (Wissenschaftsbetrieb), Glocal Public History, History Politics (Geschichtspolitik), Language: French, Public History

Serge Noiret’s post symbolizes the growing international interest in public history. This month, the International Federation for Public History (IFPH) holds its first annual conference[1] in Amsterdam with public historians coming from Europe, North and South America. Noiret’s post is about this new type of international public history in Europe, Brazil, Colombia, China, Sri Lanka and other countries hardly mentioned in traditional public history literature. In this post, Noiret rightly underlines the major questions raised by discussion on public history: what is public history? How should it be undertaken? Is there an international perspective in public history?

However, when I discuss with fellow historians, curators, archivists, or visitors, very few know about public history. Noiret is right though when he writes that one can do public history without labeling it so. This is because public history is first of all a set of practices that help historians to work for, and with, the public. Curators, archivists, collectors, genealogists, TV or Radio producers have been public historians without the title. The rise of public history since the 1970s has been an acknowledgment that non-professional historians can produce history outside universities. The relevance of non-traditional public history practices explains why the digital turn concurs with the boom of public history. The Internet and digital history are the main advertisers of public history.

If “The practice of history has always been ‘public’ in a way” as Noiret asserts, the internationalization of public history does not go without disagreements though. First, public history was born local. Noiret is perhaps overly optimistic regarding the inherent tension of an “international” public history. Only a minority of public historians has international audiences. Since public history is as much about working for the public as making history a participatory process, international projects appear all the more challenging. It is still unclear how an international public could participate in an international project.

In international discussions about public history, another worry is about the uses of the past for present purposes. Acknowledged by public historians, academic historians are – at the very least – uncomfortable with the applications of the past. Already in the early 1980s, G. Wesley Johnson noticed that German and French scholars refused to hear about historians involved in political and for-profit uses of the past.[2] In 2005 French historians founded the Comité de Vigilance face aux Usages Publics de l’Histoire whose Manifesto[3] made a clear distinction between academic history and public uses of the past. Any attempt to internationalize public history faces disagreements on the definitions and purposes of the field.

Despite the many obstacles, I agree with Noiret on the need to internationalize public history literature, projects, and forums that are mostly in English. For instance, more than 90% of the public history programs surveyed by the NCPH website are in English.[4] It is crucial to give voice to other non-English speaking networks. The international conference in Brazil demonstrates that public history has a potential international dimension. Although they may speak different languages, and be specialists in very different thematic and geographical fields, public historians communicate about practices such as oral history, cultural resources management, or digital history. Public history practices unit practitioners from all over the world. This is why public historians from North America are increasingly paying attention to what other public historians do in New Zealand, Europe, or China.[5]

Noiret finishes his post by underlining how the glocal dimension can be beneficial to public historians. Like Zachary McKiernan in his post about the utility of an international public history, he argues for building strong links between the local and the global.[6]

In focusing only on local events, for local audiences, with local actors, public history projects may become parochial. We touch here upon one crucial role for public historians: to help make sense to the past and provide a broad contextualized understanding of the past that goes beyond the personal use of history. I am convinced, as Noiret, that internationalizing pubic history can help practitioners to contribute to a better public understanding of the past. Noiret’s post opens discussion about how this internationalization can be achieved and supported. Examples of collaboration for international public history teaching, international traveling exhibitions, and international digital history projects may, as a next step, help readers to better understand the assets of an international public history. For instance, the universities of Hertfordshire (UK)[7] and North Carolina at Wilmington (USA) provide their students with the opportunities to collaborate with each-others. Likewise PhotosNormandie[8] encourages international audiences to participate in a crowdsourcing project to identify and analyze photographs of D-Day in Normandy.

Notes

[1] Website: http://publichistory.humanities.uva.nl

[2] G. Wesley Johnson, “An American Impression of Public History in Europe.” in The Public Historian 6:4 (Fall 1984), pp. 87-97.

[3] Website: http://cvuh.blogspot.ch/2007/02/manifesto-of-comite-de-vigilance-face.html

[4] More than 90% of the public history programs surveyed by the NCPH website are in English. See http://ncph.org/cms/education/graduate-and-undergraduate/guide-to-public-history-programs/ (accessed October 2014).

[5] For instance, see Jannelle Warren-Findley “The Globalizing of Public History: A Personal Journey”, in The Public Historian, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Autumn 1998), pp. 11-20.

[6] Zachary McKiernan “The Utility of an International Vision of Public History” in Public History Commons, February 2013, http://publichistorycommons.org/the-utility-of-an-international-vision-of-public-history/(accessed October 2014).

[7] Website: http://www.herts.ac.uk/apply/schools-of-study/humanities/subject-areas/minor-subjects/public-history

[8] Website: https://www.flickr.com/people/photosnormandie/.

Serge Noiret describes Public History as a “global discipline” to the effect that individual and/or societal demand for history is a global phenomenon. A phenomenon for which the practice of a “glocal” Public History seems to be a very good or even the best possible answer. We should absolutely agree with him about that point.

But speaking of Public History as a global discipline and not just a movement, we–once again–have to clarify the character of disciplines in diverse national higher education systems, to begin with the different conceptions of Public History in German Historiography and History Didactics. And first and foremost we have to (re)define the actors who interpret the past with and for the public: Are Professional Public Historians necessarily experts working outside academic settings or do ‘even’ traditional Academic Historians who are ‘willing and able’ to communicate history or rather historical knowledge in and for the public without being aware of a discipline called ‘Pubic History’ at all, belong to this group? Two supplementary notes on the “common definition of international public history” given by Serge Noiret shall encourage us to find answers for questions like these in the nearer future:

First, a research project on National Socialist forced labour in a small country town in the north of the German state Baden-Wuerttemberg during World War II which has been finished only a few months ago has shown all the numerated benefits of working on the past in a local/regional context with and for the public. Glocal research projects are attractive, because the places where history happened are usually known to us and the sound of their terminologies appears familiar. But besides the strengthening of the individuals historical situatedness in a broader living environment, there seems to be another advantage: Glocal research projects always help Public Historians to make a genuine scientific workflow more transparent for the public while working directly with and for the citizens. This is important not only for the simple reason that the legitimation of historical research activities is closely connected to the questions the public addresses at the past.

Second, the participatory Web 2.0 not only helps us to finish the one-way communication of experts who explain and file historical knowledge to the public–no dialog scheduled. Today’s external scientific communication is increasingly based on conversational formats and therefore at least closing the gap between experts, citizen scientist and a politically aware and also historically interested broader public. The participatory Web 2.0 is an important tool to take science, although to a certain extent, back to its roots: to the people who ask essential questions about history, identity, and remembrance.

Both aspects, the transparence of the genuine scientific workflow as well as the positive effects of the participatory Web 2.0, will help Public Historians to fulfil their most vital duties, that is the mediation between science and the public and the creation of a new discussion culture where historical knowledge circulates in the private and the public sphere–in an international dimension. Furthermore, both aspects are of substantial value within the (in Germany and other parts of Europe) badly needed discussion about the common grounds and the differences between History and Public History.

Replik

editorial revision from 2015/3/21, 2.15 p.m.

First of all I would like to thank Thomas Cauvin and Cord Arendes for their insights and for pushing further the discussion about internationalization of the public history field through different common practices and academic teaching. I stressed the fact that Public History with or without using the name–the practice of history everywhere with and for the public–is taking place in Europe and, maybe, always took place. I mentioned also the fact that glocal practices weren’t always referred to as being part of a specific field and/or academic discipline. And this is changing slowly today.

As an example, I quoted the 2nd conference of Brazilian Public Historians but let’s also mention the inauguration of three new Public History Masters that I know of, starting next Academic year 2015-2016 in continental Europe. Two will be launched in France. The first one is called “Histoire Publique” with a subtitle explaining better that it is about “doing history in a different way – radio, tv, web, press, museums, events: the historian is everywhere”, at the University of Paris Est, Créteil. The second one, at the University of Nimes, South of France, called master in “Histoire vivante et Archéologie expérimentale”[1]–living history and experimental archeology–and one in Italy at the University of Reggio Emilia and Modena which will keep the original English name used for the discipline, Public History for the same reasons which were mentioned by Marko Demantowsky in his PHW post last January (“Public History” – Sublation of a German Debate?”).

Furthermore, in Italy this March 2015, the 3rd edition of the 2nd level Master in History Communication (Comunicazione della Storia)[2] was celebrated at the University of Bologna. The master is focusing on public history and the media, alternative narrative, storytelling and digital history, all the different topics which were tackled during last February Public History and the Media conference at the European University Institute, Florence, Italy[3].

So, questions like what is public history and how should it be undertaken raised by Thomas in his comment to my post, are being dealt with in more structured manners in continental Europe. They are now becoming central questions raised in our global world, by new public history practitioners to engage publically with the past and public memories. This does not mean that local practitioners are all aware of such an international dimension of their activities or that a large majority of public history programs aren’t thought mainly in Anglo-Saxon countries. But it does mean in fact that public historians are engaged everywhere in similar dialogue with the past and memories within local communities and that, thanks to new digital media, the participatory web 2.0 mentioned by Cord Arendes, we now have the capacity to compare globally their practices, their methods and their aims. Participatory web and social media are showcasing publically everybody’s knowledge of the past. Even in countries where English is not used, working with the past and history is becoming a public participatory activity attracting local communities. These practitioners are more aware today of the existence of a growing institutionalized field. Hearing what different generations of Public Historians interviewed at the EUI last February[4] answered to the question “what is public history for you”, shows an instinctive convergence of theoretical intentions and practices in different countries and with different languages and culture.

Public Historians without calling themselves as such, would not embrace systematically the field but will more and more interact discussing theoretical issues and developing professional skills that aren’t often thought in classical history programs. This clearer awareness of the skills and methods needed to engage with history and communicate it in non-academic settings. Academic historians always became de facto public historians when they were engaging the past publically and to different communities locally in similar ways globally, is the result of such a new internationalisation process. New types of mediation between the use of the past and historical knowledge in the public sphere should not be undertaken only by everybody wishing to engage with the past: professional public historians should jump into the public sphere. Who’s owning the past in public–trained public historians or amateurs–answers everywhere to a bottom up curiosity and is digging into collective memories and identity issues. This global demand for the past is growing well beyond the English spoken world. Today, the web and digital technologies are supporting such a new challenge.

And this is what Cord Arendes agrees with, when he states that “Public History is a ‘global discipline’ to the effect that individual and/or societal demand for history is a global-local phenomenon”. The field is now better sustained by some new development within universities willing to prepare new professionals of the past aware of being part of a history sub-discipline. I also agree with Cord saying that confronted to what we could call a “public market of history”, traditional academic historians, amateurs and popular historians, journalists and other professionals are working in parallel with professional public historians and engage the past in public everywhere.

Public historians were always living together with academic historians in non-academic settings or academic historians always became public historians when they were engaging the past publically and using communication media like the radio, television, the film industry with their alternative forms of narratives and storytelling. The only–but important–difference between historians and non-historians working with the past is the methodological capacity to contextualize and deepen the facts and memories emerging in the public debate; but this is a fundamental difference which is understood by who’s pushing forward to develop academic public history teaching programs and the skills needed to analyze and communicate the complexity of our pasts.

References

[1] See: http://www.unimes.fr/fr/formations/catalogue/master-lmd-XB/sciences-humaines-et-sociales-SHS/master-histoire-vivante-et-archeologie-experimentale-program-master-histoire-vivante-et-archeologie-experimentale.html

[2] See Master communicazione storica (Univ. of Bologna): http://www.mastercomunicazionestorica.it (last accessed 2015/3/21).

[3] See Workshop Public History and the New Media, Florence 15: http://ifph.hypotheses.org/352; see also my post about thus conference http://dph.hypotheses.org/554 (both last accessed 2015/3/21).

[4] See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SvQnP6KAsJA&feature=youtu.be (last accessed 2015/3/21).