Abstract: The paper explores the ways in which the TV show Yellowstone and its prequels 1883 and 1923 renegotiate the myth of the American West by telling the story of the fictional Dutton family spanning from the late 19th to the early 21st centuries. Whereas complex characters and multiple plotlines bear the potential to complicate an all-too one-dimensional view on the history of the West, the shows’ overall storylines tend to reproduce the hegemonic narrative of settler colonialism.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-22009

Languages: English

Paramount’s TV serial Yellowstone pictures the US American West through the story of the fictional Dutton family and their ranch in the state of Montana. Set in the present day, the show unfolds multiple plotlines negotiating the many conflicts and contradictions between tradition and modernity, between rural conservatism and neoliberal entrepreneurship, between a self-sustained life at the frontier and the politico-economic restrictions and regulations which endanger exactly this life.

A Fictional Family, a Relatable Past

To be precise, the show features John Dutton III, a rancher constantly trying to safeguard his land and livestock, both against the demands of an indigenous community reclaiming their territories and against urban investors that try to turn untouched nature into real estate property.

At the same time, we follow his children in variations of coming-of-age narratives: We witness his daughter Beth, a manager of company mergers and acquisitions, torn in between the logics of finance capitalism and the appeal of rural roughness of ranch life, embodied by her husband Rip Wheeler, the prime ranch hand. We are made to both pity and distrust her brother Jamie, the patriarch’s foster son, a lawyer and wanna-be-politician, whose academic and judicial merits do not count at all on the ranch, and who constantly tries (and fails) to earn his (foster) father’s respect; and we see the youngest son Kayce Dutton, a former Navy SEAL, struggling with the expectation to follow John Dutton’s footsteps as much as with the family’s traditional values in general, not least due to his being married to an indigenous woman.

Providing us with the often intersecting biographies of these characters and their continuous search for belonging, Yellowstone’s narrative thread both explicitly and implicitly evokes the history of exploration and settlement, of claiming (and reclaiming) territories through centuries of violent conflict. Indeed, the Duttons become what Rebecca Weeks has called a “vehicle for history”[1] on TV, which, as she argues, is characterized by the “ability to incorporate multiple storylines” and is thus “an ideal medium for exploring historical stories”.[2]

According to Glen Cleeber, this vehicle “can combine multiple narrative levels and produce more complex histories that incorporate the personal and the political, the micro and the macro”.[3] The past becomes relatable, and at the same time remains contingent through a family who does not have any reference in the historical record, whose fictionality, as Weeks argues, “gives history itself an element of chance; the impression that things could have turned out differently.”[4]

The “Personal” and the “Political” in Yellowstone

On a plot level, the “personal” and the “political” are interwoven, e.g., in the conflict over land rights that shapes the relationship between the Dutton family and the indigenous community living in a reservation nearby – a conflict that runs through the entire serial and motivates the development of plot, conjuring up the history of the American West as a history of colonization and constant contestation. Through its distinct focus on the Dutton’s perspective, this conflict over land rights, at the same time, also unfolds as a fight of the ranching family against the interests of large real estate companies from the urban centers on the US-American East coast that endanger what John Dutton in particular considers a way of life worth defending at all costs.

In this triangular relationship between indigenous demands for restitution and resettlement, white rural conservatism, and the threat of gentrification, the serial indeed connects the personal to the political, as it raises questions about the legitimacy of ownership, which is claimed by different (groups of) characters with different interests and perspectives – more often than not, in a law-abiding and violent fashion. The West is still wild, the show lets us know.[5]

The contested history of the American West is also thematized through the constellation of characters within the Dutton family: John Dutton’s daughter in law, Monica Long-Dutton, a granddaughter of an indigenous elder, whose family had been living on the Northwestern territories for generations, represents the voice of indigeneity: An academic and teacher in the field of indigenous studies, she is torn between the love to her ancestry and the love to her husband Kayce, and at times manages to irritate the overwhelmingly white patriarchal way of life on the ranch. Her husband’s decision to spend part of his family life on the “Broken Rock Indian Reservation” allows the show to (re)produce a specific idea of the indigenous community, which is shown to be characterized by a clash between tradition and modernity.[6]

Between Revisionism and Conservation

According to Taylor Sheridan, this arrangement of personae and their individual trajectories is part of what he considers to be “‘responsible storytelling’ by emphasizing the gravity of consequences. In a Western setting,” as Variety magazine reports, “these consequences often translate to bloody deaths and sacrifice, usually for protection of family or property. The series was inspired in part by Clint Eastwood’s revisionist Westerns and the screenwriter’s first-hand experience growing up on a ranch in Waco, Texas.”[7]

Indeed, one might argue that Yellowstone, through its complex storytelling and character development, gives room to perspectives that do not necessarily reproduce an all-too one-dimensional view of the American West. In this sense, then, the show does justice to de Groot’s characterization of the Western as “a fundamentally revisionist genre […] signaled through its diegetic rejection of easy populist narratives.”[8]

Even more so, through exposing these “easy populist narratives” that de Groot specifically locates in performances of Rodeo as the “ultimate pointless expression of cowboy culture”[9] (which is frequently featured in the show) and through the incorporation of multiple points of view, Yellowstone could be read as reproducing and reflecting on the ways of imagining the West at the same time, “both telling a story and suggesting that the way the story is presented is deeply problematic.“[10] In so doing, the show potentially contributes to “open[ing] up discursive spaces where ideas about the past, desire, time, horror, nationhood, identity, chaos, legitimacy, and historical authority are debated.”[11]

Whereas for Sheridan, Yellowstone “present[s] wildly progressive notions,”[12] there have been other voices that problematize this reading: Variety magazine, for instance, in which Sheridan’s defense of the show is quoted, concludes that “it can sometimes be tricky to balance those progressive notions with promoting a show that appeals to a large swath of the country,”[13] which might well consider Yellowstone an affirmation of patriarchal America.

Indeed, the serial, even though acknowledging the conflicts and contradictions of American expansionism, reproduces hegemonic structures and ideologies much more than it questions them. It does not come as a surprise, then, that critics have labelled it “the Republican show”, “anti-woke”,[14] or – also due to its epic proportions and an astonishingly similar opening soundtrack – a “‘redneck version’” of HBO’s Game of Thrones.[15]

A Word on the Prequels: 1883 and 1923

A similar debate unfolded regarding the show’s prequels 1883 and 1923. The former, which narrativizes the journey of the Dutton family to the American West in the second half of the 19th century, was heralded by some reviewers as a critical variation of the traditional Western, as “a revisionist take on the genre […] Instead of optimism and triumph, it’s a saga of failure and survival.”[16] Equally enthusiastic reviews praised 1923 for its sinister view on the Prohibition and the Great Depression. Moreover, the story of the indigenous girl Teonna and her escape from a white religious school “was universally praised by most critics, with many sighting it as an important acknowledgment of the revisionist way Indigenous Americans were portrayed in older Westerns.”[17]

At the same time, however, the prequels reproduce mainstream historical narratives. Sure, the story of 1883 is told from the perspective of Elsa Dutton (whose voiceover frames and directs the narrative), which might bend the usually male view in historiographical accounts. Yet, it equally reproduces this view through Elsa’s mimicry of a cowboy’s way of life, which helps her gain her father’s respect.[18]

Moreover, in 1883, history is still produced from a white perspective, which may well be more sensitive to the hardship of life at the frontier, but is not revisionist at all. Quite the contrary: It might even be said to affirm the established (hi)story of the American West exactly through its focus on suffering, turning the way West into a way of sacrifice for a better life (in the case of the Duttons, a life in Montana, which is displayed in a Garden-of-Eden fashion at the end of the serial).

Accordingly, other reviewers had different takes on 1883 and its (alleged) revisionist character, arguing that it may paint a darker picture of the American West, but, instead of putting its myth into a question, enhances its cultural and ideological significance.[19]

Productive Ambivalence?

As media of cultural memory, the three shows serialize history and turn its periods into pre- and sequels – with 1883 and 1923 forming an origin story that leads up to and helps explain the Dutton’s way of life in Yellowstone. In so doing, the shows certainly engage in and foster discourse on US American history – they “contribute to the historical imaginary, having an almost pedagogical aspect in allowing a culture to ‘understand’ past moments.”[20]

At the same time, through their ‘pre- and sequelization’ of history, the shows foster a very specific understanding of the past, suggesting linearity and causality as central principles of historical developments. Moreover, though their fictionality might create contingency and options to include alternative visions of the past, it still relies on established, i.e., hegemonic narratives and perspectives in its retelling of the American West.

It is perhaps this ambivalence, then, and the debates it stimulates, which makes the serials even more powerful in the shaping of US American public history.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Rabitsch, Stefan. “’When you look at a calf, what do you see?’ Land(ed) Business, Necrotic Entrepreneurialism, and Competing Capitalisms in the Contemporary West of Yellowstone.” Journal of the Austrian Association for American Studies 3, no. 2 (2022): 235–259.

- Wanzo, Rebeacca. “Taylor Sheridan is Sorry But His Characters are Not: The Messiness of Categorizing Conservative Television.” Film Quarterly 76, no. 2 (2022): 78–82.

- Weeks, Rebecca. History by HBO: Televising the American Past. Lexington: The University of Kentucky Press, 2022.

Web Resources

- Katie Reul, “‘Yellowstone’ Director Taylor Sheridan Defends Series Against ‘Anti-Woke’ Claims,” https://variety.com/2022/tv/news/yellowstone-director-taylor-sheridan-defends-series-against-anti-woke-claims-1235430905/ (last accessed 28 August 2023).

- Katherine Sidnell, “Yellowstone is being described as ‘redneck’ Game Of Thrones and viewers are hooked,” https://www.ladbible.com/entertainment/yellowstone-described-as-redneck-game-of-thrones-092302-20230130 (last accessed 28 August 2023).

_____________________

[1] Rebecca Weeks, History by HBO: Televising the American Past (Lexington: The University of Kentucky Press, 2022), 87.

[2] Ibid., 100.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid., 92.

[5] For a much more comprehensive reading of this dimension of Yellowstone, i.e., its focus on “the entrepreneurial and ideological wranglings over land” (246) and its portrayal of “the latent and ongoing effects that settler colonialism and its entanglements with the necrotic logic of capitalism have on lifeworlds in the contemporary West” (237), see Stefan Rabitsch’s “’When you look at a calf, what do you see?’ Land(ed) Business, Necrotic Entrepreneurialism, and Competing Capitalisms in the Contemporary West of Yellowstone,” in Journal of the Austrian Association for American Studies 3/2 (2022), 235–259.

[6] See Joe Dolce’s “Yellowstone: Gambling for Big Stakes,” in Quadrant Magazine, April 2020, 94–97, which focuses on Yellowstone’s representation of the indigenous communities; see also Rabitsch, specifically 248ff., including his discussion of the character of Monica (ibid., 251).

[7] Katie Reul, “‘Yellowstone’ Director Taylor Sheridan Defends Series Against ‘Anti-Woke’ Claims,” https://variety.com/2022/tv/news/yellowstone-director-taylor-sheridan-defends-series-against-anti-woke-claims-1235430905/ (last accessed August 28, 2023) The article quoted here draws on an interview Sheridan gave The Atlantic.

[8] Jerome de Groot, The Past in Contemporary Historical Fiction (London/New York: Routledge), 55.

[9] Ibid., 56.

[10] Ibid., 61.

[11] Ibid., 2.

[12] Reul, “‘Yellowstone’”.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Katherine Sidnell, “Yellowstone is being described as ‘redneck’ Game Of Thrones and viewers are hooked,” https://www.ladbible.com/entertainment/yellowstone-described-as-redneck-game-of-thrones-092302-20230130 (last accessed August 28, 2023). For a more thorough analysis of this ambivalence in Sheridan’s show, see Rebecca Wanzo’s “Taylor Sheridan is Sorry But His Characters are Not: The Messiness of Categorizing Conservative Television,” in Film Quarterly 76/2 (2022), 78–82.

[16] Adi Tantimedh, “1883 Reveals Taylor Sheridan’s Primal Myth of the American Frontier,” https://bleedingcool.com/tv/1883-reveals-taylor-sheridans-primal-myth-of-the-american-frontier/ (last accessed August 28, 2023).

[17] Zachary Moser, “1923 Reviews: What Critics Thought Of The Yellowstone Prequel Series,” https://screenrant.com/1923-reviews-yellowstone-prequel/ (last accessed August 28, 2023).

[18] Similarly, by the way, to Beth Dutton’s stereotypically masculine way of sorting relationships and solving conflicts, which regularly impresses the Dutton patriarch in Yellowstone.

[19] Daniel Fienberg, for instance, in the Hollywood Reporter, argues that “the series is actually a straightforward period Western and not even of the revisionist variety”, whose first episode is already “packed with stereotypes” and whose message could be “summarized as ‘Man, the Old West was rough’, which is sure to come as a revelation to anybody who hasn’t seen a Clint Eastwood film, Deadwood or played Oregon Trail”, cf. Daniel Fienberg, “Paramount+’s ‘1883’: TV Review,” https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/tv/tv-reviews/1883-review-1235064853/ (last accessed August 28, 2023). Specifically in right-wing and conservative contexts, the serial was characterized as “a compelling and brave depiction of the sacrifices that built this country […] In 1883, we see vividly the blood, sweat, and tears soaked into the foundation of our country.” Emily Jashinsky, “There’s Hope In ‘1883’ And The Dawn Of The ‘Yellowstone’ Universe,” https://thefederalist.com/2022/03/01/theres-hope-in-1883-and-the-dawn-of-the-yellowstone-universe/ (last accessed August 28, 2023). In this sense then, 1883 – and in a similar way, Yellowstone and 1923 – also lend themselves to be cited in populist discourse as embodiments of a ‘true’ – and white – America.

[20] De Groot, The Past, 2.

_____________________

Image Credits

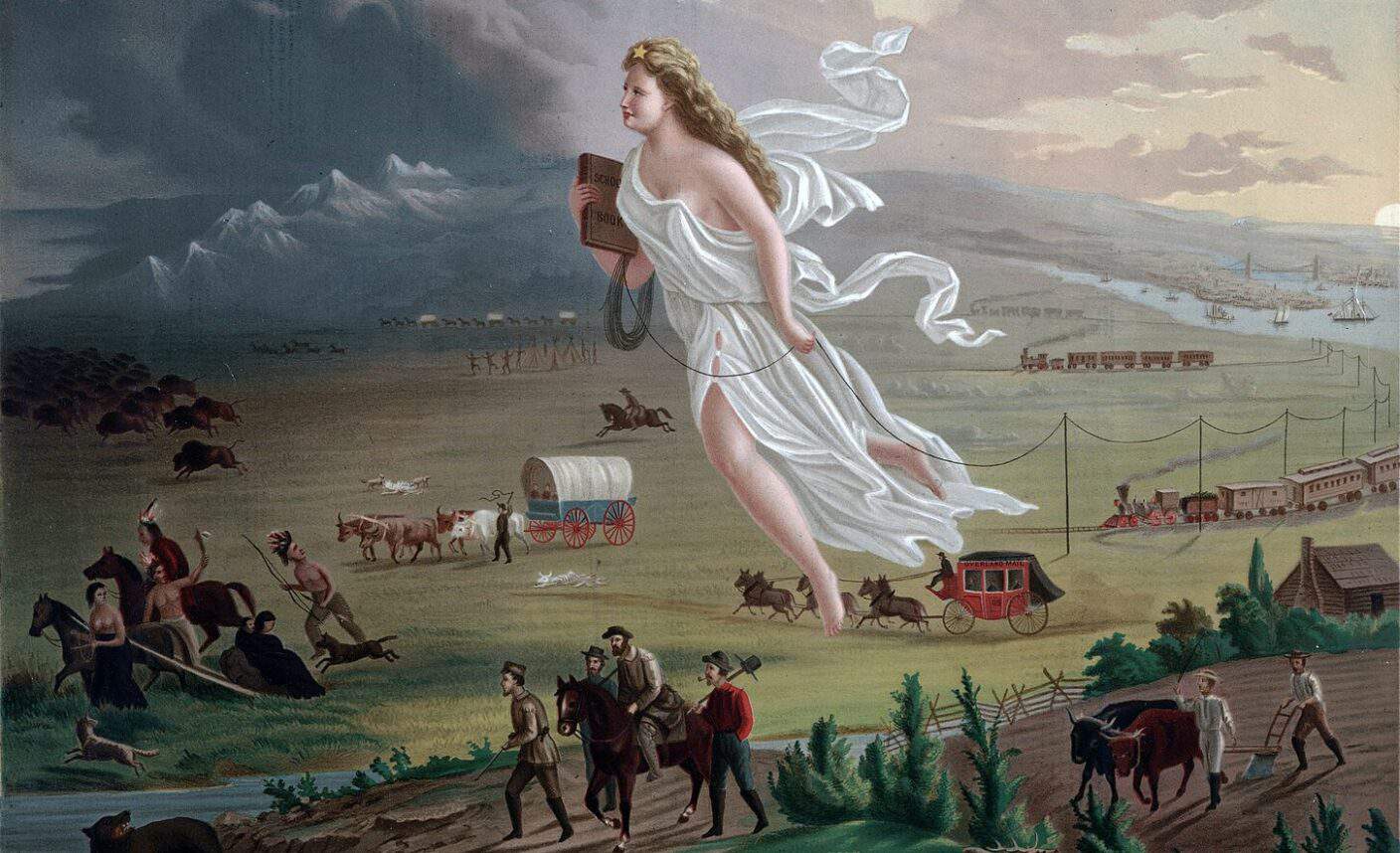

“American Progress” by John Gast, Public Domain via Commons.

Recommended Citation

Butler, Martin: Serial (Hi)Stories: The American West on TV. In: Public History Weekly 11 (2023) 6, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-22009.

Editorial Responsibility

Copyright © 2023 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 11 (2023) 6

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-22009

Tags: Colonial Legacy (Koloniales Erbe), Popular Culture, TV (Fernsehen), USA

To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

OPEN PEER REVIEW

Clint Eastwood’s Western Unforgiven as an inspiration for Yellowstone

According to the author the three successful Western series, 1883, 1923, Yellowstone follow central principles of historical developments: “linearity and causality”. It is therefore not surprising when well-established narratives of this genre like hegemonic ideologies are subtly carried along with this serial (hi)story of the American West. And it’s even less surprising with Clint Eastwood’s Western movies as a main source of inspiration for the creator of the series, Taylor Sheridan. The highly acclaimed TV-series Yellowstone and its prequels are said to be Western, but different, Clint Eastwood’s highly acclaimed Unforgiven is a Western, but different, too. A brief comparison is worthwile.

When we see the main character in Unforgiven, William Munny (Clint Eastwood), the first time, we see him as a bent old man: dirty, poor, weak, trying to catch his pigs. He rather looks like a ‘Pigman’ than a Cowboy – very different from a traditional Western hero and also very different from Clint Eastwood as an actor in former Western movies. At the end of the movie the anti-hero from the beginning is gone. We see Munny’s little farm house, but no longer a bent old, dirty, poor, weak man. The farm is abandoned. Munny changed his life; he left the life we’ve seen at the beginning of the movie. Isn’t that a real (Western-)hero-story: an anti-hero has been transformed into a hero? What caused that transformation? What happened between beginning and ending? A woman has been mistreated. The authorities are not willing to ensure justice. So it’s William Munny’s job to restore justice. Standing for justice is the main task for him and a lot of other main characters in Eastwood films. Those heroes have to fight for justice because the authorities (in the US) are weak and incompetent in that fight. In 1883, 1923 and Yellowstone it is not an individual, but a family – an ‘extended individual’ – who fights for justice. This narrative is often told in Eastwood movies and occurs in, e.g., The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976) and Gran Torino (2008).

Despite the differences between Unforgiven and former Eastwood Western movies there are consistent narratives. Unforgiven was highly acclaimed for its differences, but the unchanged was rarely noticed. Something similar seems evident in Yellowstone and its prequels. The series “still relies on established, i.e., hegemonic narratives and perspectives in its retelling of the American West”, as the author concisely points out. The well-known narratives continue to be carried along, but they are subtly lost in the supposedly new. They are, so to say, visible-invisible remnants and a testimony of a bygone historical culture which is still active in genres of popular culture.