from our “Wilde 13” section

Abstract: Although recent research advises that professional development should be active and engage participants through personal discovery, most Australian history teachers tend to experience passive, didactic teaching delivered in lectures, symposia, and workshops. Few offerings provide opportunities for teachers to participate in immersive discovery learning that is relevant to their teaching needs. In this article we examine the impact of a 5-day archaeology professional development experience designed to give teachers practical knowledge and experience of archaeology, enliven their teaching of history, and improve their students’ literacy capabilities.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21021

Languages: English

For most history teachers in Australia, professional development (PD) tends to be a passive experience delivered by experts at conferences in the form of didactic lectures, symposia, and workshops. More recently, passive learning for PD became more common during COVID-19 lockdowns with the switch to virtual conferences. Although teachers have enthusiastically embraced student-centred learning in their own classrooms, the delivery of teacher PD has managed to resist the constructivist movement of the 1980s and ‘90s which places the learner at the centre of the pedagogy.[1] Few PD sessions focus on skills acquisition facilitated by the teacher’s participation in active, discovery learning.

Teacher Professional Development

In contrast, research advises that teacher PD is most effective when it is content focused, incorporates active learning and supports collaboration in job-embedded contexts.[2] Active, experiential learning engages participants in learning through personal discovery. It has the potential to improve learning and retention because the learner focuses their attention on knowledge acquisition and is then required to apply it to their work context. Effective PD for teachers should include a central problem of practice that it aims to inform, and a pedagogy that will help teachers enact new ideas, translating them into the context of their own practice.[3]

While plenty of research exists on history pedagogy, little attention has been paid to the impact of history PD on teachers’ pedagogy when they return to the classroom, and its subsequent impact on their own students. There is also a notable lack of research on the impact of archaeology PD on teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge[4] and its impact on teachers’ personal and professional praxis.

Since the introduction of the Australian Curriculum in schools from 2013, archaeology has become integrated in mandatory history in Years 7 and 8 (ages 12-14) and elective senior Ancient History (ages 17-18).[5] The dilemma is that teachers are expected to teach about archaeology, even though it is likely they did not study archaeology in their initial teacher education course or participate in an archaeological excavation. Most teachers can teach about the discoveries of archaeology but find it difficult to understand the details of archaeological research methods because they have not actively participated in the process.

In January 2019, I [Zarmati] ran an archaeology field school for five secondary history teachers who participated in the excavation of a demolished 1827 military guard house in the colonial heritage town of Oatlands, Tasmania (Australia). What follows is an insight from a teacher participant into the impact of that experience on his praxis.

Archaeology Professional Development

My aim was to provide a small number of Australian history teachers with a practical, immersive experience of excavation that would increase their knowledge and skills of archaeological methods and encourage deep learning through personal discovery and collegial collaboration. The excavation also had a practical purpose for the Oatlands community; the site was to be investigated and prepared for the local council to provide safe, public access and interpretive signage.

Five teachers participated in:

- Preparatory learning. Before they arrived in Tasmania, teachers accessed a custom-designed website containing information about the history of Oatlands, the historical context of the guard house site, and information about the processes of excavation;

- Pedagogy workshops focused on archaeological thinking[6] and creative ideas for teaching and learning archaeology in and out of the classroom (e.g., ‘Dig-in-a-box’, ‘How to set up a simulated excavation in your school’ and 3-D photogrammetry) and transferring knowledge from one context (excavation) to another (classroom).

- Five days of excavation, including measuring and laying out an excavation trench, taking electronic measurements, recording, categorising and labelling finds and features, analysing and interpreting finds in context and interpreting archaeological features and artefacts.

In the next section, history teacher David Nally describes the knowledge and skills he acquired during the excavation and explains how he applied them to teaching his own students about Australian history.

Bringing Archaeology into the Classroom

I [Nally] was motivated to sign up for the dig because each time I had to teach my students about archaeology, I suffered from imposter syndrome! Despite having taught history for 7 years, I worried about my capability because I was required to have practical knowledge of archaeological excavation. Although I was confident about teaching archaeological methods and historiography from what I had learnt in textbooks, I also realised the learning activities I developed for my classes were not genuinely prompting open-ended inquiry, but rather eliciting a closed loop of standard, comprehension answers.

The skills I learned on the dig were the direct result of immersive, experiential learning. They helped me expand my ideas about what might take place in my own classroom, and how I could replicate real-world, authentic experiences for my students. Inspired by my own learning during the dig, I designed learning activities for students that were carefully sequenced to deepen the process of inquiry. The slow process of putting together the pieces of artefacts and reimagining the site did, however, demonstrate the difficulties of conducting a genuine open-ended inquiry in the classroom. I learned that sometimes there is simply not enough evidence to answer inquiry questions and that some things will remain unresolved.

These are the considerations that influenced the learning activity I implemented in my school after the Oatlands dig. They had a profound impact on the lessons I designed to enliven my teaching of history and prompt my students to ‘think archaeologically’.

Hands on History

I designed an archaeology-based intervention in collaboration with a Literacy Consultant to produce a set of resources that would encourage students’ engagement and, hopefully, improve their written literacy skills. The teaching team for Year 9 [15-year-olds] consisted of five teachers for six classes, who taught a unit on the Industrial Revolution.

The first activity involved students examining artefacts from the Oatlands excavation and following the process of archaeological analysis by responding to these prompts:

- What do you think the artefact is? Why do you think that?

- How would you describe the artefact?

- What else would you need to find out to better understand the artefact?

- After handling the artefact, what questions do you have about nineteenth century Australia?

In one of the excavation workshops, I learned how to facilitate inquiry learning by prompting students to draw interpretations about how artefacts used by people in Oatlands in the 19th and 20th centuries reflected significant changes in technology over time. For example, we discovered that nails demonstrated the shift from a cottage-based industry to factory-based production, a small marble was the remnant of a bespoke small-scale glass production. Sheep bones prompted a lively discussion amongst students about which animal they belonged to, as well as how they might reflect aspects of everyday life in the town.

The artefacts anchored students’ archaeological thinking and theorising via ‘history as mystery’ learning activities, where students discussed their interpretations of the contexts and circumstances in which they were found. I was able to tell students that after its initial life as a military building, the guard house was used by four generations of a family who ran a butchery business on the site – hence the proliferation of sheep bones.

My students’ exposure to material evidence allowed them to see how much their own world had changed since this time. In the process, my teaching was more explicitly linked to showing how human experiences in the classroom can be anchored in a real-world context by repeated exposure to these artefacts throughout the unit.

Writing History from Archaeology

Students’ development in archaeological thinking was measured in their writing samples. We began our first lesson with teachers explaining to students the historical context and how the Oatlands artefacts were products of the Industrial Revolution. The teaching team collected writing samples every three lessons. Every fourth lesson, students reviewed writing samples from across the grade as part of a marking workshop. Students produced their writing samples by independently analysing additional visual and written evidence about the Industrial Revolution and its impact on Australian culture.

After samples were collected, teachers selected 3-4 exemplars from across the grade to analyse how well students had responded to the writing stimulus. Teachers then conferred to moderate standards for high, medium, and low responses. The result of four cycles of the writing process over 13 weeks was reflected in students’ summative assessment results. Across Year 9, with a sample size of 170 students, 96% demonstrated improvement from their first assessment task of between 2-47% in their second assessment task. The majority of gains were between 10-15%, with the lower percentage gains being amongst the already higher scoring grades.

Impacts of Archaeology on Students’ Literacy

This case study demonstrates that by combining an archaeology-based pedagogy with a literacy focus, teachers can boost the quality of students’ writing about history. Students’ writing samples showed measurable improvements in sentence construction, grammar, and logical flow of argument. Students also demonstrated increased clarity in their descriptions of primary sources and their understanding of large-scale changes in technology over time.

For teachers, learning how to think archaeologically helped them understand the process of historical inquiry and refine their skills of teaching primary source analysis and interpretation. Continued professional dialogue about improvements in students’ writing increased teachers’ collegiality and confidence in their pedagogical content knowledge.

We conclude with the words of one 15-year-old student who describes the impact of using archaeology to learn about history:

‘One of the main things that helped was the artefacts. It helped me really think about where these things had come from and how they were originally used. […] The interactive activities [got] me involved in what we are learning.’

_____________________

Further Reading

- Zarmati, Louise. “Sparking the flame, not filling the vessel: How museum educators teach history in Australian museums.” Historical Encounters 7, (3) 2020: 76-91, https://www.hej-hermes.net/vol7-no3 (last accessed 9 January 2023).

- Gibbs, Martin, Sarah Colley. “Digital preservation, online access and historical archaeology ‘grey literature’ from New South Wales, Australia.” Australian Archaeology, 75:1 2012, 95-103, DOI: 10.1080/03122417.2012.11681957.

Web Resources

- The Big Dig Archaeology Education Centre: https://thebigdig.com.au/ (last accessed 9 January 2023).

- Australian Museum Archaeology: https://australian.museum/learn/cultures/atsi-collection/australian-archaeology/ (last accessed 9 January 2023).

- ABC Ancient Archaeology: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iuCfZk0jsMo (last accessed 9 January 2023).

_____________________

[1] For a summary of the development of constructivism in education, see Chu Chih Liu and I Ju (Crissa) Chen, “Evolution of Constructivism,” Contemporary Issues in Education Research (CIER) 3 (4) 2010: 63. https://doi.org/10.19030/cier.v3i4.199.

[2] Linda Darling-Hammond, Maria E. Hyler, and Madelyn Gardner, Effective Teacher Professional Development (Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute, 2017), https://doi.org/10.54300/122.311.

[3] Mary M. Kennedy, “How Does Professional Development Improve Teaching?,” Review of Educational Research 86 (4) 2016: 945–80. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315626800.

[4] Lee Shulman, “Knowledge and Teaching: Foundations of the New Reform,” Harvard Educational Review 57 (1) 1987: 1–23. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411. Shulman defines pedagogical content knowledge as ‘a complex system of knowing the material to be taught, having an understanding of children, of learning and teaching, effective classroom management and having a mastery of techniques for teaching the material to learners’.

[5] Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Rerporting Authority, Australian Curriculum (ACARA), https://v9.australiancurriculum.edu.au/ (last accessed 9 January 2023).

[6] Louise Zarmati, “Thinking Archaeologically About Australia’s Deep Time History,” Teaching History: Journal of the History Teachers’ Association of NSW, 56 (1) 2022: 14-21. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.476383508594717 (last accessed 9 January 2023).

_____________________

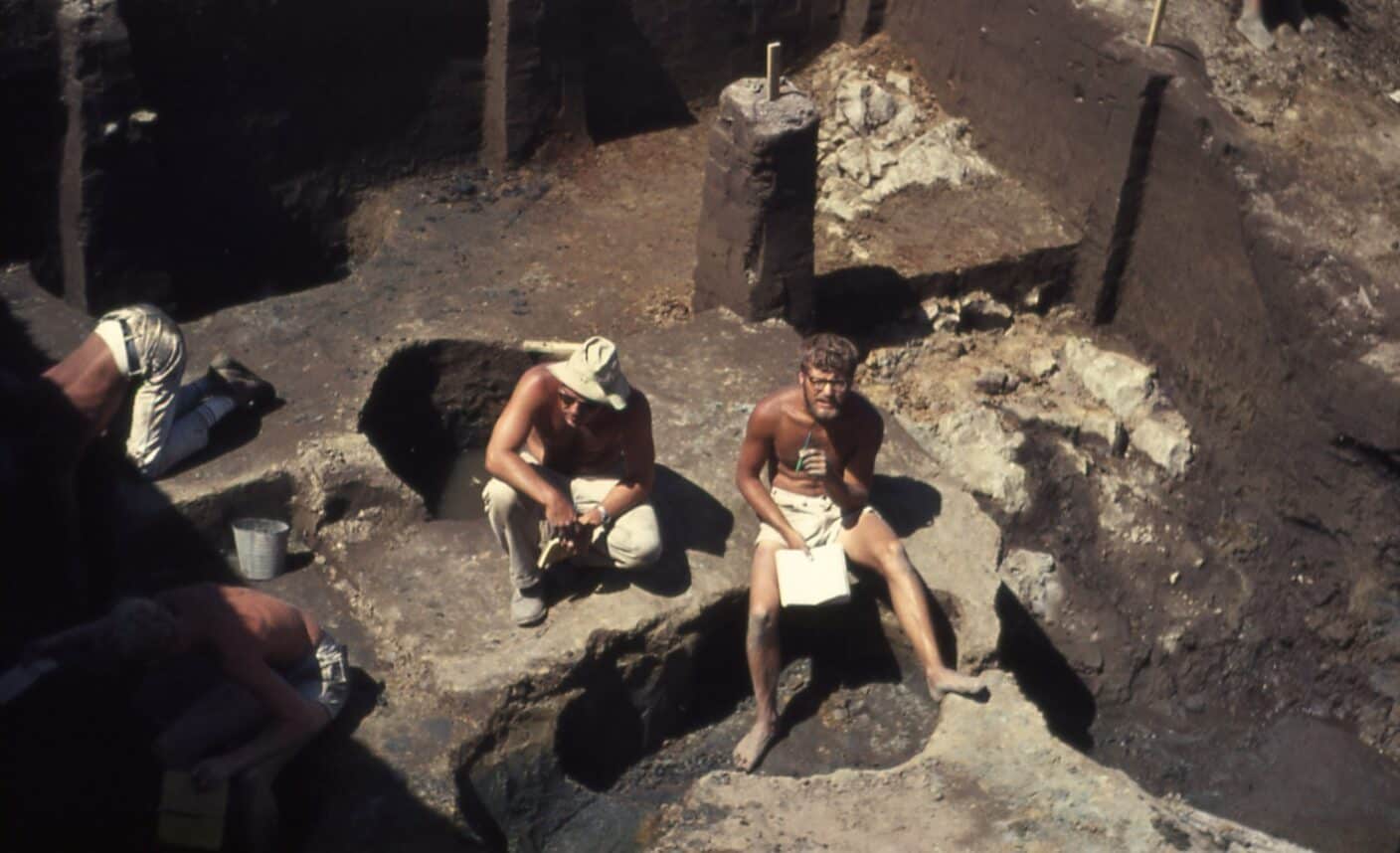

Image Credits

Archaeological excavations at the Wildcat Canyon site, Oregon (USA), 1966 © John Atherton CC BY-SA-2.0 via flickr.

Recommended Citation

Zarmati, Louise, David Nally: The Impact of Archaeology on History Teachers’ Pedagogy. In: Public History Weekly 11 (2023) 1, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21021.

Editorial Responsibility

Copyright © 2023 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 11 (2023) 1

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21021

Tags: Archaeology (Archäologie), Australia (Australien), History Didactics (Geschichtsdidaktik), Participation (Partizipation)

To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

OPEN PEER REVIEW

Direct and Indirect Benefits

This article highlights both direct and indirect benefits of archaeology professional development (PD) on pedagogy. The authors’ opening observation that PD tends to be passive and didactic and therefore relatively ineffective in changing practice prompts some valuable reflection. A great deal of professional development for teachers is provided by other teachers, yet the pedagogies used in PD are generally not reflective of what is regarded as good practice, particularly in the discipline of history. With the strong influence of Peter Sexias’ historical thinking in the Australian Curriculum: History,[1] we expect our students to be actively engaged in their learning through inquiry, yet we accept ‘death by powerpoint’ for our own learning. The author’s description of effective PD could equally apply to the goals teachers have for their own history students: “Effective PD for teachers should include a central problem of practice that it aims to inform, and a pedagogy that will help teachers enact new ideas, translating them into the context of their own practice”. This active and inquiry-driven approach to PD is under-researched, a gap which this paper aims to fill.

The approach which underpinned the PD included preparatory learning focusing on content about the area, pedagogy workshops focused on archaeological thinking and a five day excavation. This blend of substantive knowledge acquisition, explicit engagement with skills and then application in an authentic setting closely mirrors the process of effective student-centred inquiry pedagogy.[2] The teacher narrative included in the paper also emphasised how active and authentic engagement in their PD was mirrored in their later teaching practice; “In the process, my teaching was more explicitly linked to showing how human experiences in the classroom can be anchored in a real-world context by repeated exposure to these artefacts throughout the unit”. This transmission of inquiry-driven practice from the PD to the classroom would be a space that warrants further research and discussion and this paper makes a strong first contribution to this space.

The author has a strong focus on the way in which engagement with archaeological artefacts had an impact upon student literacy, showing meaningful gains. The teacher’s focus on “archaeological thinking” clearly showed how the pedagogy workshops influenced their practice directly, with the archaeological experience itself being a support for this pedagogical innovation. It is important to note the explicit and iterative teaching of historical writing skills as part of this approach: it is a skill to be developed and refined, rather than good historical writing being perceived as a logical outcome of historical learning. The implications for student skill development and assessment performance here are a valuable finding and highlight the connections between inquiry learning and assessment.[3]

A perhaps underexplored element was the significance of local connections to both the PD and the later teaching that took place. PD tends to be a closed process, one of knowledge transmission and personal implementation which is context-agnostic. However, both the teacher narrative and the student comments highlight how influential the use of local artefacts and archaeological experience was to their learning and teaching. As I have argued elsewhere,[4] local area studies provide rich opportunities to bring history to life and make connections to students’ own experiences, something that both the teacher and student noted as a major benefit of this PD and subsequent teaching and learning. While this particular study focused on a colonial site, there is also clear potential for connections to be made to local First Nations histories in applying this PD approach in other archaeological projects.

This paper is a valuable conversation-starter in the under-researched area of history teacher professional development. The benefit of the inquiry-centred and practical PD on teacher practice and subsequent student outcomes is clearly articulated. The paper also raises some interesting prompts for further investigation into the effective implementation of local area studies (including archaeology) and the explicit teaching of skills like historical writing. This will be of particular interest to History teaching associations and other organisations that offer teacher professional development, and also provide archaeologists with a model for involving history teachers in practical learning on dig sites as well as the wider history teacher educator and researcher communities.

_____

[1] Seixas, P. (2006), Benchmarks of Historical Thinking: A Framework for Assessment in Canada. http://historicalthinking.ca/sites/default/files/files/docs/Framework_EN.pdf

[2] Bedford, A. (2022). Critical and Collaborative Problem-solving: An Action Research Project on the Development of Cognition-Centred Inquiry for Year 11 Senior History. International Coalition of Girls’ Schools Global Action Research Collaborative. https://girlsschools.org/research/garc/categories/building-problem-solving-capacity/page/2/

[3] Sharp, H. (2021), “Assessment in the History classroom: Incorporating inquiry approaches”, Agora, 56(2), 21-24.

[4] Bedford, A. (2021). “An Education in Commemoration: The Australian Curriculum, Commemoration and Memorials” in Kerby, M., Baguley, M., Gehrmann, R., & Bedford, A. A Possession Forever: A Guide to Using Commemorative Memorials and Monuments in the Classroom https://usq.pressbooks.pub/apossessionforever/chapter/chapter-6-education-in-commemoration-the-australian-curriculum-commemoration-and-memorials/