Abstract: Debates on the constructed or the real basis of collective identities have persisted for decades, with debate focusing around the extent to which such identities are arbitrary and imposed from above, organic and developed from below, or some permutation of these possibilities. These debates can be enriched by consideration of narratological issues. Collective identity narratives often operate through binary schemas – defining a collective ‘us’ against an other ‘them’ – and through simplistic and melodramatic narrative templates. This article brings these analytical optics to bear on recent populist mobilizations in the UK, exploring ‘austerity’ and ‘Brexit’ populist collective identity stories in their left and right variants and arguing that we can see some recent shifts in narrative strategy in collective identity discourse on the right.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2020-14972.

Languages: English, German

Collective identity narratives aim to “bring together,” “collect” and unify. They tend to do so, however, by positing an ”other” — to distinguish the collective from and against. Contemporary populist narratives tend to foreground “othering” to a remarkable degree. Is there a future for “collectivity” in an age of division?

(De)Construction

Debates about the “constructed” nature of collective identities have persisted for decades. Where national collective identities are concerned, an emphasis on “invention” is frequent — most notably in The Invention of Tradition, a classic of the genre.[1] National collective identities are often thought of as instruments of “legitimation and mobilization, through which leaders and elites stir up mass support for their competitive power struggle.”[2] There have been numerous projects to reshape collective identities in the United Kingdom in recent decades, ranging, on the one hand from Tony Blair’s “Cool Britannia” to talk of creating a “Britannia Unchained” and “Empire 2.0” more recently.[3]

There are problems with thinking of “construction“ in these ways, however. As Thompson argued in The Making of The English Working Class, collective identities can be constituted “from below” as much as “from above.” In addition, whilst recognizing that conceptualisations have the power to shape experienced and lived realities, one has to ask “what” is it that is being shaped and constructed in social constructivist discourse.[4] As Smith has argued, if we must talk of “invention,” then it must be understood, at least in part, as “a novel recombination of existing elements.”[5]

Recognizing that identities are not simply conjured out of thin air does not mean, however, that we should think of collective identities as things that are simply made up of objects “out there.” Processes of identity construction work by gathering “a multitude of individuals with a multitude of experiences” into a collective.[6] These are processes of identification with and identification against through which individuals come “to feel an identity of interests as between themselves” and an identity of interests “as against” some others.[7] Such processes of identification often have material determinants. They also have narrative psychological determinants, as Levi argued, and operate through a “friend-enemy dichotomy” feeding a “Manichean tendency to reduce the river of human events to conflicts and conflicts to duels” between “us and them.”[8] Class identity narratives, such as those that Thompson examined, point to divisions within a national collective. National narratives of the kind analysed by Linda Colley and others posit divisions outside the nation, between a national “us” and a foreign “them.”[9]

Varieties of Austerity Populism

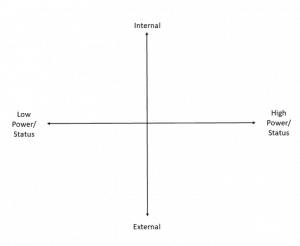

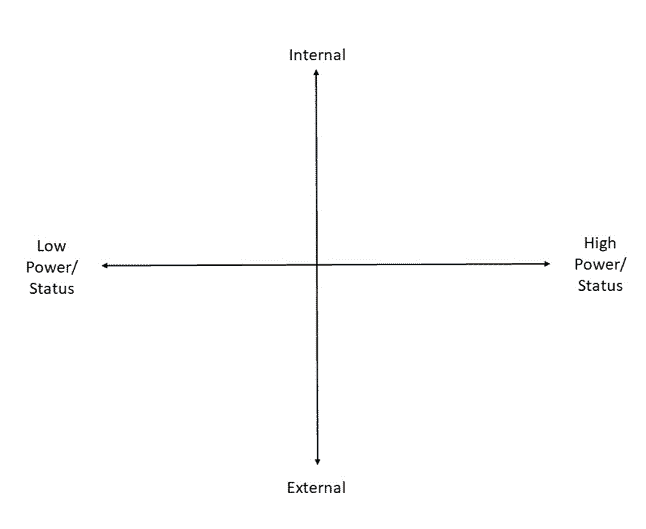

One does not have to look very far to find real material determinants shaping recent collective identity discourses in the United Kingdom — the 2008 economic crash and the decade of “austerity” that followed it. What is particularly striking about the evolution of recent politics, however, is the prevalence of binary identity discourses, which follow the kind of melodramatic narrative structure highlighted by Levi. These are divisive narratives as much as collective ones — about “them” as much as about “us.” We can distinguish between varieties (a) that define “them” as “high“ or “low“ status and varieties (b) that define “them” as either internal “enemies within” or as external “enemies without.”

Differentiating “them” – a schema

As Bolton and Pitts have argued, in the aftermath of the financial crash alternative forms of “austerity populism” arose to explain what had happened.[10] These narratives shared structural features, even though their content differed dramatically: a simplistic moral economy in which material difficulties are represented as damage done to “us” by a culpable “them.”

Right austerity populism — of the kind cultivated by the British government in the first half of the last decade — sought to mobilize “hard working families“ against a posited underclass living fecklessly on benefits. In right austerity populism, the problem was an “enemy within“ and this enemy was low in power and status. In left austerity populism, by contrast, the “enemy” was identified as high status and powerful financial elites outside the country — in “tax havens” and elsewhere — operating “immorally” and placing profit above social need.

Similar narratives arose in the Brexit debate and many varieties of Brexit populism could be identified. Populism that sets up a virtuous “us” against a low-status threat from outside is exemplified by UKIP’s notorious “Breaking Point” poster from the 2016 Brexit campaign which identified the EU with the “threat” of mass migration from Turkey.[11] Brexit populisms focused on an external and high-status enemy are exemplified by the slogans of the campaign itself — such as the notorious claim that “we” sent £350 million in weekly tribute to the EU. This was a narrative that pro-Brexit populists could identify with positively. Anti-Brexit populists, on the other hand, interpreted such slogans as evidence of manipulation of elections by internal high-status figures (media owners, hedge fund managers and so on).[12]

What forms did populist narratives play in the 2019 election? This is no place for a systematic analysis but a gesture in the direction can be achieved in the space available. What contrasts in narrative strategy were apparent in the introductions to their manifestos signed by the leaders of the two main political parties — Labour and Conservative?

Real Change — For the Many, not the Few

The Labour leader’s manifesto introduction has many of the features of the populisms described above. It posits an “us” / “them” binary, positioning “the many” against “the few.” The former is described as suffering cuts and hardships and the latter as immoral free riders.

It’s time to take on the vested interests holding people back. The last decade has seen a wealth grab by a privileged few, supported by the Conservatives, at the expense of the majority. The big polluters, financial speculators and corporate tax-dodgers have had a free ride for too long.[13]

In other words, the text posits an internal enemy with high status and power and blames them for the people’s current predicament.

The table below compares the incidence of a number of words and topics in both the Labour and the Conservative texts. A comparison was made of the use of the personal pronouns “we” and “they” — yet revealed little difference. Similarly, little of importance appeared when the two documents were compared in terms of self-reference to party names. Striking differences emerge when past and future were compared, however. This was also true when reference to past and future threats were compared: 12.1% of the Labour text was about the past and 9.2% of the text focused on those posited as causing present problems.

Table 1: Comparisons of the percentage of words and topics present in the leaders’ introductions to the Conservative and Labour manifestos 2019

| Words | Conservative Party Manifesto Introduction | Labour Party Manifesto Introduction |

| We | 3.42% | 2.6% |

| They | 0.39% | 0.2% |

| References to own party name | 0.16% | 1.4% |

| Past tense | 3.73% | 12.1% |

| References to those blamed for current difficulties | 0.86% | 9.2% |

| Future-focused negative comments on the other party | 16.72% | 1.0% |

| All items in this table | 25.27% | 26.5% |

Release that Lion from its Cage

By contrast with the Labour manifesto introduction, the Conservatives made very little reference to current difficulties or those who might be blamed for them (0.86% of the text). The country was described as “trapped, like a lion in a cage,” as “stuck” and as “paralysed by a broken Parliament.” Again, an internal enemy with high status and power (the Parliament) was blamed for the country’s current predicament but hardly anything else was said about problems in the present. The text also focused almost exclusively on what would be done if the Conservative Party were elected.

By contrast with Labour — who do spend time attributing blame for past actions — the Conservative text devotes significant space (16.72%) to identifying future problems that it claims would arise if the Labour Party were elected, as, for example in the following:

The… modern Labour Party… detest the profit motive… and would raise taxes so wantonly — that they would destroy the very basis of this country’s prosperity.[14]

Conclusion

Since becoming leader, Johnson has sought to distinguish his politics from the Conservativism of the “austerity” period and this is apparent in the text which spent very little time identifying past problems and very little time attributing blame — issues that were key to “austerity populism.” We have a new variant of populist collective identity narrative here, perhaps. One that still offers simple solutions, but one that does so foregrounding positive futures and not negative presents and pasts. Like all populisms, this collective identity story must have an enemy against whom the positive representative of “we” / “us” can be contrasted. Again, however, the focus was on the future – albeit a dystopian one from which the representative of “we” / “us” could save the people.

Whether there is a future for populist collective identity stories is a question for a futurologist. What does seem clear, however, is that future-oriented populisms seem in the ascendant in England.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Bolton, Matt, and Frederick Harry Pitts. Corbynism: a Critical Approach. Bingley: Emerald Publishing, 2018.

-

Barnett, Anthony. Lure of Greatness. Penguin Random House, 2018.

Web Resources

- It’s Time for Real Change: The Labour Party Manifesto 2019: https://labour.org.uk/manifesto-2019/accessible-manifestos/ (last accessed 24 February 2020).

- Get Brexit Done: Unleash Britain’s Potential. The Conservative and Unionist Party Manifesto 2019: https://vote.conservatives.com/our-plan (last accessed 24 February 2020).

_____________________

[1] Eric Hobsbawm and Terrence Ranger (Eds.), The Invention of Tradition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, (2012).

[2] Anthony D. Smith, “Nationalism and the Historians.,” in Mapping the Nation, ed. Gopal Balakrishnan (London: Verso, 1996), 187.

[3] Tom Campbell and Homa Khaleeli, “Cool Britannia Symbolised Hope – but All It Delivered Was a Culture of Inequality,” The Guardian July 5, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/inequality/commentisfree/2017/jul/05/cool-britannia-inequality-tony-blair-arts-industry (last accessed 24 February 2020); Andy Beckett, “Britannia Unchained: the Rise of the New Tory Right,” The Guardian, August 22, 2012, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2012/aug/22/britannia-unchained-rise-of-new-tory-right (last accessed 24 February 2020).

[4] Ian Hacking, The Social Construction of What? (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000).

[5] Anthony D. Smith, “Nationalism and the Historians.,” in Mapping the Nation, ed. Gopal Balakrishnan (London: Verso, 1996), 191.

[6] Edward Palmer Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (London: Penguin Books, 2013), 10.

[7] Edward Palmer Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (London: Penguin Books, 2013), 11.

[8] Primo Levi and Ann Goldstein, The Complete Works of Primo Levi (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, A Division of W.W. Norton & Company, 2015), 2431.

[9] Linda Colley, Britons: Forging the Nation 1707-1837 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

[10] Matt Bolton and Frederick Harry Pitts, Corbynism: a Critical Approach (Bingley: Emerald Publishing, 2018), 33-42.

[11] Heather Stewart and Rowena Mason, “Nigel Farage’s Anti-Migrant Poster Reported to Police,” The Guardian, June 16, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/jun/16/nigel-farage-defends-ukip-breaking-point-poster-queue-of-migrants (last accessed 24 February 2020).

[12] Alan Travis, “The Leave Campaign Made Three Key Promises – Are They Keeping Them?,” The Guardian, June 27, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/jun/27/eu-referendum-reality-check-leave-campaign-promises (last accessed 24 February 2020).

[13] The Labour Party. (2019). It’s Time for Real Change: The Labour Party Manifesto 2019 (Large Print Manifesto). The Labour Party. https://labour.org.uk/manifesto-2019/accessible-manifestos/ (last accessed 24 February 2020).

[14] The Conservative Party. (2019). Get Brexit Done: Unleash Britain’s Potential. The Conservative and Unionist Party Manifesto 2019. The Conservative Party. https://vote.conservatives.com/our-plan (last accessed 24 February 2020).

_____________________

Image Credits

The Britons Protection © 2020 Arthur Chapman.

Recommended Citation

Chapman, Arthur: Collecting and Dividing Identities in the Age of Brexit. In: Public History Weekly 8 (2020) 2, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2020-14972.

Editorial Responsibility

Moritz Hoffmann / Marko Demantowsky (Team Basel)

Kollektive Identitätsnarrative zielen darauf ab, “zusammenzuführen,” “zu sammeln” und zu vereinen. Sie tendieren jedoch dazu, dies zu tun, indem sie ein “Anderes” postulieren — um das Kollektiv von und gegen etwas zu unterscheiden. Zeitgenössische populistische Narrative neigen in bemerkenswertem Maße dazu, das “Othering” in den Vordergrund zu stellen. Hat das “Kollektiv” im Zeitalter der Spaltungen eine Zukunft?

(De)Konstruktion

Die Debatten über die “Konstruiertheit” kollektiver Identitäten dauern seit Jahrzehnten an. Wenn es um nationale kollektive Identitäten geht, wird häufig der Schwerpunkt auf “Erfindung” gelegt — vor allem in The Invention of Tradition (Die Erfindung der Tradition), einem Klassiker des Genres.[1] Nationale kollektive Identitäten werden oft als Instrumente der “Legitimation und Mobilisierung” betrachtet, “durch die Führer und Eliten die Unterstützung der Massen für ihren wetteifernden Machtkampf heraufbeschöwen”.[2] In den letzten Jahrzehnten gab es im Vereinigten Königreich zahlreiche Projekte zur Neugestaltung kollektiver Identitäten, die einerseits von Tony Blairs “Cool Britannia” bis hin zur Rede von der Schaffung eines “Britannia Unchained” und in jüngerer Zeit des “Empire 2.0” reichten.[3]

Es ist jedoch problematisch, auf diese Weise über “Konstruktion” nachzudenken. Wie Thompson in The Making of The English Working Class argumentierte, können kollektive Identitäten sowohl “von unten” als auch “von oben” konstituiert werden. Obwohl man sich bewusst ist, dass Konzeptualisierungen fähig sind, erfahrene und gelebte Realitäten zu formen, muss man sich darüber hinaus jedoch fragen, “was” genau im sozial-konstruktiven Diskurs geformt und konstruiert wird.[4] Wenn wir, wie Smith argumentiert hat, von “Erfindung” sprechen müssen, dann muss sie zumindest teilweise als “eine neuartige Rekombination von bestehenden Elementen” verstanden werden.[5]

Zu erkennen, dass Identitäten nicht einfach aus dem Nichts heraufbeschworen werden, bedeutet jedoch nicht, dass wir kollektive Identitäten als Dinge betrachten sollten, die einfach aus Objekten “da draußen” bestehen. Prozesse der Identitätskonstruktion funktionieren, indem sie “eine Vielzahl von Individuen mit einer Vielzahl von Erfahrungen” zu einem Kollektiv zusammenfassen.[6] Es handelt sich um Prozesse der Identifikation mit und gegen etwas durch die Individuen, “eine Identität der Interessen untereinander” und eine Identität der Interessen “gegen” andere zu empfinden.[7] Solche Identifikationsprozesse haben oft materielle Determinanten. Sie haben auch narrativ-psychologische Determinanten, wie Levi argumentierte, und operieren durch eine “Freund-Feind-Dichotomie”, die eine “manichäische Tendenz, den Fluss menschlicher Ereignisse auf Konflikte und Konflikte auf Duelle zu reduzieren” zwischen “uns und ihnen” nährt.[8] Klassenidentitätsnarrative, wie die von Thompson untersuchten, weisen auf Spaltungen innerhalb eines nationalen Kollektivs hin. Nationale Narrative, wie sie von Linda Colley und anderen analysiert wurden, weisen auf Spaltungen außerhalb der Nation hin, zwischen einem nationalen “wir” und einem fremden “sie”.[9]

Varianten des Austeritätspopulismus

Man muss nicht sehr weit suchen, um echte materielle Determinanten zu finden, die die jüngsten kollektiven Identitätsdiskurse in Großbritannien prägen — den Wirtschaftscrash von 2008 und das darauf folgende Jahrzehnt der “Austerität.” Besonders auffallend an der Entwicklung der jüngsten Politik ist jedoch die Prävalenz binärer Identitätsdiskurse, die der von Levi hervorgehobenen Art der melodramatischen Erzählstruktur folgen. Es handelt sich um spaltende Erzählungen ebenso wie um kollektive — über “sie” ebenso wie über “uns”. Wir können unterscheiden zwischen Varianten (a), die “sie” statusmäßig als “hoch” oder “tief” definieren, und Varianten (b), die “sie” entweder als “Feinde im Inneren” oder als “äußere Feinde” definieren.

Die Differenzierung von “sie” – ein Schema

Wie Bolton und Pitts argumentiert haben, entstanden nach dem Finanzcrash alternative Formen des “Austeritätspopulismus”, um die Geschehnisse zu erklären.[10] Diese Erzählungen hatten strukturelle Merkmale gemeinsam, auch wenn sie sich inhaltlich dramatisch unterschieden: eine vereinfachte moralische Ökonomie, in der materielle Schwierigkeiten als Schaden dargestellt werden, den ein schuldhaftes “sie” “uns” zufügt.

Der rechte Austeritätspopulismus — wie er von der britischen Regierung in der ersten Hälfte des letzten Jahrzehnts gepflegt wurde — versuchte, “hart arbeitende Familien” gegen eine angebliche nutzlose Unterschicht zu mobilisieren, die auf Sozialleistungen angewiesen ist. Im rechten Austeritätspopulismus war das Problem ein “innerer Feind”, mit wenig Macht und Status. Im linken Austeritätspopulismus hingegen wurde dem “Feind” ein hoher Status innerhalb der britischen Gesellschaft zugeschrieben oder er gehörte zu mächtigen Finanzeliten außerhalb des Landes (in “Steueroasen” und anderswo ansässig), die “unmoralisch” operierten und den Profit über die soziale Not stellten.

In der Brexit-Debatte entstanden ähnliche Narrative, und es konnten viele Varianten des Brexit-Populismus identifiziert werden. Populismus, der ein tugendhaftes “wir” gegen eine geringe Statusbedrohung von außen aufstellt, wird durch das berüchtigte “Breaking Point”-Plakat der UKIP aus der Brexit-Kampagne 2016 veranschaulicht, die die EU mit der “Bedrohung” durch eine Massenmigration aus der Türkei identifizierte.[11] Brexit-Populismen, die sich auf einen äußeren und hochrangigen Feind konzentrieren, werden durch die Slogans der Kampagne selbst veranschaulicht — wie die berüchtigte Behauptung, dass “wir” der EU wöchentlich 350 Millionen Pfund zu Ehren schicken. Mit diesem Narrativ konnten sich Pro-Brexit-Populist*innen positiv identifizieren. Anti-Brexit-Populist*innen hingegen interpretierten solche Parolen als Beweis für die Manipulation von Wahlen durch inländische Persönlichkeiten mit hohem Status (Medienbesitzer, Hedge-Fonds-Manager und so weiter).[12]

Welche Formen nahmen populistische Erzählungen bei der Wahl 2019? Dies ist kein Ort für eine systematische Analyse, aber ein kurzer Hinweis ist dennoch möglich. Welche Gegensätze in der Erzählstrategie zeigten sich in den Einleitungen zu ihren Manifesten, die von den Führern der beiden wichtigsten politischen Parteien — Labour und Konservative — unterzeichnet wurden?

Zeit für echte Veränderung — für die Vielen, nicht die Wenigen

Die Manifest-Einführung des Labour-Führers weist viele der oben beschriebenen Merkmale des Populismus auf. Es stellt ein “wir” und “sie” binär einander gegenüber und positioniert “die vielen” gegen “die wenigen”. Erstere leiden an Kürzungen und Entbehrungen während letztere als unmoralischer Trittbrettfahrer beschrieben werden.

Es ist an der Zeit, es mit den versteckten Interessen aufzunehmen, die die Menschen zurückhalten. In den letzten zehn Jahren haben einige wenige Privilegierte, unterstützt von den Konservativen, auf Kosten der Mehrheit nach Reichtum gegriffen. Die großen Umweltverschmutzer, Finanzspekulanten und Unternehmenssteuerhinterzieher hatten zu lange einen Freifahrtschein.[13]

Mit anderen Worten, der Text postuliert einen inneren Feind mit hohem Status und großer Macht und macht ihn für die gegenwärtige Notlage des Volkes verantwortlich.

Tabelle 1 (siehe unten) vergleicht die Häufigkeit einer Reihe von Wörtern und Themen sowohl im Labour- als auch im Konservativen-Manifest. Verglichen wurde die Verwendung der Personalpronomen “wir” und “sie” — dies ergibt kaum Unterschiede, ebenso der Vergleich hinsichtlich des Bezuges zum eigenen Parteinamen. Auffällige Unterschiede ergeben sich jedoch, wenn Vergangenheit und Zukunft verglichen werden, und dies gilt auch, wenn der Bezug auf vergangene und zukünftige Bedrohungen verglichen wird: 12,1 % des Labour-Textes betreffen die Vergangenheit und 9,2 % des Textes konzentrieren sich auf diejenigen, die als Verursacher*innen gegenwärtiger Probleme angeführt werden.

| Wörter | Einleitung zum Manifest der Konservativen Partei | Einleitung zum Manifest der Labour-Partei |

| Wir | 3.42% | 2.6% |

| Sie | 0.39% | 0.2% |

| Verweise auf den Namen der eigenen Partei | 0.16% | 1.4% |

| Vergangenheitsform | 3.73% | 12.1% |

| Verweise auf diejenigen, die für die derzeitigen Schwierigkeiten verantwortlich sind | 0.86% | 9.2% |

| Zukunftsgerichtete negative Kommentare über die andere Partei | 16.72% | 1.0% |

| Alle Elemente in dieser Tabelle | 25.27% | 26.5% |

Den Löwen loslassen

Im Gegensatz zur Einleitung des Labour-Manifests weisen die Konservativen nur sehr wenig auf die aktuellen Schwierigkeiten oder diejenigen, die dafür verantwortlich gemacht werden könnten, hin (0,86% des Textes). Das Land wird als “gefangen, wie ein Löwe im Käfig”, als “festgefahren” und als “durch ein zerbrochenes Parlament gelähmt” beschrieben. Wiederum wird ein interner Feind mit hohem Status und Macht (das Parlament) für die gegenwärtige Notlage des Landes verantwortlich gemacht, aber es wird kaum etwas anderes über die Probleme in der Gegenwart gesagt. Der Text konzentriert sich auch fast ausschließlich darauf, darzulegen, was im Falle einer Wahl der Konservativen Partei geschehen würde.

Im Gegensatz zur Labour-Partei, die vor allem Schuld für vergangene Handlungen zuweist, widmet der konservative Text viel Raum (16,72%) der Identifizierung zukünftiger Probleme, von denen sie behauptet, dass sie im Falle einer Wahl der Labour-Partei auftreten würden, wie z.B. im Folgenden:

Die… moderne Labour-Partei… verabscheut das Profitstreben… und würde die Steuern so mutwillig erhöhen — dass sie die Grundlage des Wohlstands dieses Landes zerstören würden.[14]

Fazit

Seit seiner Wahl zum Partei-Führer hat Boris Johnson versucht, seine Politik vom Konservativismus der “Austeritätsperiode” zu unterscheiden. Dies wird im Text deutlich, der sehr wenig Raum dafür einräumt, vergangene Probleme zu identifizieren und Schuld zuzuweisen — beides Schlüssel zum “Austeritätspopulismus”. Wir haben es hier vielleicht mit einer neuen Variante der populistischen kollektiven Identitätserzählung zu tun. Eine, die immer noch einfache Lösungen bietet, aber eine, bei der die positive Zukunft im Vordergrund steht und nicht die negative Gegenwart und Vergangenheit. Wie alle Populismen muss diese kollektive Identitätsgeschichte einen Feind haben, gegen den die positiven Vertreter*innen des “wir” / “uns” kontrastiert werden kann. Doch auch hier steht die Zukunft im Mittelpunkt — wenn auch eine dystopische, aus der die Vertreter*innen des “wir” / “uns” das Volk retten können.

Ob es eine Zukunft für populistische kollektive Identitätsgeschichten gibt, ist eine Frage für Zukunftsforscher. Klar ist jedoch, dass in England zukunftsorientierte Populismen im Aufstieg begriffen sind.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Bolton, Matt, and Frederick Harry Pitts. Corbynism: a Critical Approach. Bingley: Emerald Publishing, 2018.

- Barnett, Anthony. Lure of Greatness. Penguin Random House, 2018.

Webressourcen

- It’s Time for Real Change: The Labour Party Manifesto 2019: https://labour.org.uk/manifesto-2019/accessible-manifestos/ (letzter Zugriff 24. Februar 2020).

- Get Brexit Done: Unleash Britain’s Potential. The Conservative and Unionist Party Manifesto 2019: https://vote.conservatives.com/our-plan (letzter Zugriff 24. Februar 2020).

_____________________

[1] Eric Hobsbawm and Terrence Ranger (Eds.), The Invention of Tradition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, (2012).

[2] Anthony D. Smith, “Nationalism and the Historians.,” in Mapping the Nation, ed. Gopal Balakrishnan (London: Verso, 1996), 187.

[3] Tom Campbell and Homa Khaleeli, “Cool Britannia Symbolised Hope – but All It Delivered Was a Culture of Inequality,” The Guardian July 5, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/inequality/commentisfree/2017/jul/05/cool-britannia-inequality-tony-blair-arts-industry (letzter Zugriff 24. Februar 2020); Andy Beckett, “Britannia Unchained: the Rise of the New Tory Right,” The Guardian, August 22, 2012, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2012/aug/22/britannia-unchained-rise-of-new-tory-right (letzter Zugriff 24. Februar 2020).

[4] Ian Hacking, The Social Construction of What? (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000).

[5] Anthony D. Smith, “Nationalism and the Historians.,” in Mapping the Nation, ed. Gopal Balakrishnan (London: Verso, 1996), 191.

[6] Edward Palmer Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (London: Penguin Books, 2013), 10.

[7] Edward Palmer Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (London: Penguin Books, 2013), 11.

[8] Primo Levi and Ann Goldstein, The Complete Works of Primo Levi (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, A Division of W.W. Norton & Company, 2015), 2431.

[9] Linda Colley, Britons: Forging the Nation 1707-1837 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

[10] Matt Bolton and Frederick Harry Pitts, Corbynism: a Critical Approach (Bingley: Emerald Publishing, 2018), 33-42.

[11] Heather Stewart and Rowena Mason, “Nigel Farage’s Anti-Migrant Poster Reported to Police,” The Guardian, June 16, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/jun/16/nigel-farage-defends-ukip-breaking-point-poster-queue-of-migrants (letzter Zugriff 24. Februar 2020).

[12] Alan Travis, “The Leave Campaign Made Three Key Promises – Are They Keeping Them?,” The Guardian, June 27, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/jun/27/eu-referendum-reality-check-leave-campaign-promises (letzter Zugriff 24. Februar 2020).

[13] The Labour Party. (2019). It’s Time for Real Change: The Labour Party Manifesto 2019 (Large Print Manifesto). The Labour Party. https://labour.org.uk/manifesto-2019/accessible-manifestos/ (letzter Zugriff 24. Februar 2020).

[14] The Conservative Party. (2019). Get Brexit Done: Unleash Britain’s Potential. The Conservative and Unionist Party Manifesto 2019. The Conservative Party. https://vote.conservatives.com/our-plan (letzter Zugriff 24. Februar 2020).

_____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

The Britons Protection © 2020 Arthur Chapman.

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Chapman, Arthur: Einigende und trennende Identitäten in Brexit-Zeiten. In: Public History Weekly 8 (2020) 2, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2020-14972.

Redaktionelle Verantwortung

Moritz Hoffmann / Marko Demantowsky (Team Basel)

Copyright (c) 2020 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 8 (2020) 2

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2020-14972

Tags: History Politics (Geschichtspolitik), Identity (Identität), UK (Grossbritannien)

To all our non-English speaking readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 8 European languages. Just copy and paste.

Interesting piece that stimulated a number of thoughts. My own work with how young people (YP) use manifestations of social memory to construct their identities was informed, following Hall, 1980 to think about how they decode the construction of identities in order to counter privileging an exploration of the way which artefacts of social memory, such as texts, films etc. are encoded rather than decoded.

What I found was, as here, YP processes of identification are influenced by both material and narrative psychological determinants. Wertsch’s work, offer ways of understanding social memory, accounting for both the way in which it is produced socially but also worked on individually. This approach is grounded in the use of textual resources, especially narratives. Nevertheless critical to his conceptualisation is seeing people as ‘active agents’ in a process of gaining mastery over ‘cultural tools’.

What I found was that was that these processes were located within specific sociocultural moments and reflect particular social and cultural settings. And that these settings are not fixed, but are open to both temporal and spatial changes he says hopefully!

In terms of future-oriented populisms it might be worth reading Bill Schwarz excellent essay in embers of empire in Brexit Britain. He reminds us ‘the properties of the new ethic populism were a product of the age of imperial democracy.’ Not that Farage is Carson rather he suggest ‘if we alter the angel of vision and think conceptually in terms of the contingent, mobile relations between state and nation then this recurrent pattern of different variants of ethnic populism, in the plural, may be helpful.”

To all our non-English speaking readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 8 European languages. Just copy and paste.

Very interesting post, especially in positing a ‘futurist populism’. I suppose the complication is that while the slogans of Leave/Conservative are not necessarily backward looking in the same way as Trumpism – ‘Make America Great Again’ – they are dependent on a lot of spoken or unspoken views of the British past: empire = more good than bad; ‘standing alone’ against the Nazis etc. etc.

I think the attention to the fine detail of language is really important. I’m interested in the use of euphemisms as well: ‘elite’ doesn’t mean rich or posh, it actually means metropolitan/cosmopolitan (another euphemism).