Abstract: Sports history is an ideal vehicle for conveying historical and socially relevant questions to the public. People are thrilled by sport, it becomes economically more and more important and it is omnipresent in the media. Sports history as a cultural heritage, however, endures a wallflower existence, at least in Switzerland. Underfinanced or heroicizing museums and little presence in classrooms open up opportunities for new forms of public history.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-13304.

Languages: English, Deutsch

Sports history is an ideal vehicle for conveying historical and socially relevant questions to the public. People are thrilled by sport, it becomes economically more and more important and it is omnipresent in the media. Sports history as a cultural heritage, however, endures a wallflower existence, at least in Switzerland. Underfinanced or heroicizing museums and little presence in classrooms open up opportunities for new forms of public history.

Dramatic Situations

In autumn 2018 the Swiss Sports Museum in Basel gone into liquidation had to close its doors. By the liquidation the historically valuable collection even faced the threat of sale: Roger Federer’s racket as well as old photographs on glass plates would then have come under the hammer and have ended up in private collections. At the last minute a rescue plan could be designed so that the collection will now remain preserved as total stock and be brought to Biel. It is still unclear whether and how it will remain accessible to research and to the broad public. Furthermore, owing to disintegration valuable objects, files and photographs threaten to get lost in private collections as well as in the archives of sports clubs and the respective historical knowledge dwindles from generation to generation.

The extreme example of the Swiss Sports Museum is perhaps not even so atypical for the discrepant importance of sports history in Switzerland. On the occasion of major sports events, the media is quick to mention the sporting tradition, past successes and the importance of sport for Switzerland. At the same time, sport is so short-lived that its cultural heritage is neglected in day-to-day business. In several respects, the cultural memory finds itself, as it were, in a strange position: Sport was and still is male-dominated, accordingly are the memories. What’s more, cultural memories strongly focus on popular, high-turnover sport disciplines such as soccer, ice hockey and skiing.

Sports History in Museums

This can also be observed in the current museum landscape of Switzerland. Whereas the Swiss Sports Museum also covered numerous marginal sports and women’s sport, the largest museums, namely the FIFA Museum in Zurich and the Olympic Museum in Lausanne, mainly attract tourists and school classes with up-to-date major sporting disciplines. Particularly striking, moreover, is that both the museums tend to deal with their own past in a rather uncritical manner: Corruption or the role of both the associations during the National Socialist era hardly play a role at all. Both museums are strongly present in dramaturgy and in conveying emotions. The FIFA Museum furthermore puts great emphasis on gamification. An entire floor comprises a kind of play palace for the young and the young at heart, children can color pre-designed templates with exclusively male stars. Digital forms of mediation play a major role in both the sports museums, in particular on interactive maps and concerning sports statistics.[1]

New Forms of Mediation of Sports History

As elsewhere in Europe the mediation of history via digital forms is also promoted in Switzerland. Over the last few years several positive projects were thus created in the field of public history. Last year the FC Zurich Museum played a pioneering role.[2] Because of the neglection of the public memory of women’s soccer in Switzerland a blog was set up which works on the principle of crowdsourcing. Former players bring their photo albums and personal souvenirs to the museum where they are digitized and explained in the blog. Furthermore, there are videos of contemporary witnesses who tell about the beginnings of women’s soccer in Switzerland. For example, the stories of how women had to struggle against any types of resistances and gender-stereotypical prejudices. Sports history comes alive and is emotionally perceivable by contemporary witnesses. What’s more, for 2020 an exhibition for the 50-year anniversary of Swiss women’s soccer is planned which is also designed as a travelling exhibition for schools and sports clubs.

The Swiss Sports History Digital Portal

A project aiming in a similar direction was launched last year as well. The Swiss Sports History Digital Portal which is in the process of being established shall facilitate the access to sports history for different user groups throughout Switzerland and without language barriers. The aim is to preserve and convey the historical heritage of Swiss sports. The portal serves research, the media and the mediation in schools and consists of three pillars:

– Mediation and networking: A timeline and a short video shall provide a first orientation. Researchers and media professionals who for their fields need to work with specific materials, in particular audiovisual sources, are given quick and uncomplicated access to a broad pool.

– Exploitation: The portal shall, on the one hand, make already existing and newly exploited source inventories visible on the net. This pillar also provides know-how and help for associations which want to better preserve their archive material and thus to make available their cultural heritage to future generations.

– Learning tools and low-threshold communication in schools and sports clubs: The portal conveys research findings which are prepared for schools and sports clubs. In a first phase, this happens on the topic of integration and exclusion in Swiss sports. By means of an interactive online tool as well as a direct contact to contemporary witnesses, children and adolescents shall be sensitized for the fact that it is no coincidence who practiced and still practices what kind of sport and when. Young people thereby learn that the history of sports does not limit itself to past victories and defeats.

This project domiciled at the University of Lucerne and Zurich closely cooperates with the University of Teacher Education Lucerne and the Institute of Memory Cultures located there as well as nationwide with museums and other memory and education institutions. This portal will be launched in summer 2019.

Into the Digital Future?

The future will show how successful such web-based projects will be. There is at least hope that reinvigorated research on sports history in Switzerland can lead to a new understanding.[3] The dangers are well-known: Insufficient sustainable financing, neglection of the already existing forms of mediation, simplification of the contents. Nonetheless, it can be said that digitization offers great chances and opportunities: Easy participation of the public, integrability into the curricula, the reaching of new participating target groups. It, however, seems crucial to me to do one thing and not neglect the other: Museums and archives have to continue to exist and to be publicly funded. Also, because the haptic experience of the objects will never be replaceable and the cultural heritage of sports should also continue to exist via museum mediation. Last but not least, the digitization of knowledge will remain a phantasm since it can never comprise all library, archive and museum areas. There is simply a lack of time and resources for this. The discrepancy between medial, economic and present-day-related attention towards sports and the neglection of its cultural heritage becomes also apparent in the funding policy of the Swiss Federal Office of Culture: Sports history did not play any role in the cultural heritage year of 2018 at all.[4] This will hopefully be changed in the future.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Jucker, Michael et al., eds. Masse, Märkte und Macht in der Geschichte des Sports. Zürich: Chronos, 2016.

- Haxal, Daniel, “The National Football Museum and the FIFA World Football Museum,” Journal of Sporthistory 45, no. 1 (2018): 96-98.

- Gautschi, Peter. “Gamification as a Miracle Cure for Public History?,” Public History Weekly 6, no. 37 (2018). dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-13011..

Web Resources

- Projektwebsite des Vermittlungsprojekts: https://www.sportshistory.ch (last accessed 15 January 2019).

- Blog des FC Zürich-Museums zum Frauenfussball: https://seit1968.ch (last accessed 15 January 2019).

- Sportmuseum Schweiz: https://www.sportmuseum.ch (last accessed 15 January 2019)

_____________________

[1] Daniel Haxal, “The National Football Museum and the FIFA World Football Museum,” Journal of Sport History 45, no. 1 (2018): 96-98. Robert Kossuth and Carly Adams, “Reflections on Critical Sport History in the Museum: Opportunities and Challenges from a Local/Regional Project,” Journal of Sport History 40, no. 2 (2013): 285-295.

[2] See the web resources. Both projects also cooperate with the Association for Swiss Sports History, www.sportshistory.ch (last accessed 15 January 2019). Further mediation projects of scientific contents are available at https://www.science-et-cite.ch/de and https://www.grstiftung.ch/de/handlungsfelder/scientainment.html (last accessed 15 January 2019).

[3] Martin Crotty, “Sport, Popular Culture, and the Future: Some Commentary,” Journal of Sport History 40, no. 1 (2013): 57-67. On the latest research in Switzerland see the forthcoming: Thomas Busset, Christian Koller, und Michael Jucker, eds., Nouvelles recherches sur l’histoire du sport en Suisse (Neuchâtel: Editions CIES, 2019) in print, see also: Grégory Quin, “Writing Swiss Sport History: A Quest for Original Archives,” The International Journal of the History of Sport 34, no. 5-6 (2017): 432-436.

[4] See https://kulturerbefueralle.ch (last accessed 15 January 2019).

_____________________

Image Credits

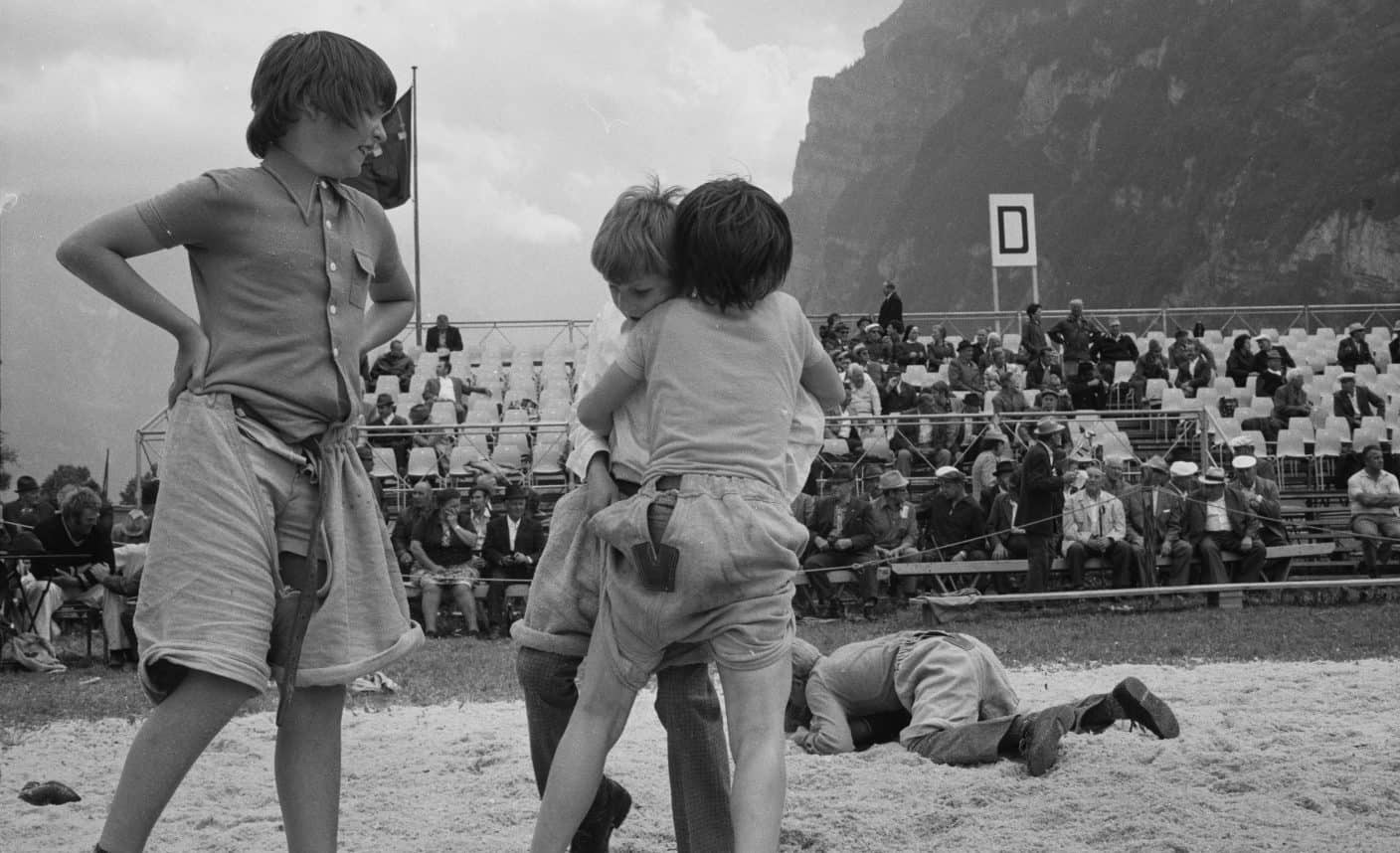

Näfelser Schwingfest, undated © ETH Zürich e-pics

Translation

Kurt Brügger, swissamericanlanguageexpert (www.swissamericanlanguageexpert.ch/)

Recommended Citation

Jucker, Michael: Sports History as Threatened Public History. In: Public History Weekly 7 (2019) 4, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-13304.

Sportgeschichte ist ein ideales Vehikel, um historische und gesellschaftsrelevante Fragen öffentlich zu vermitteln. Sport begeistert, wird ökonomisch immer bedeutender und ist in den Medien omnipräsent. Sportgeschichte als kulturelles Erbe jedoch fristet zumindest in der Schweiz ein Mauerblümchendasein. Unterfinanzierte oder heroisierende Museen und wenig Präsenz im Schulunterricht bilden jedoch Chancen für neue Formen der Public History.

Dramatische Zustände

Im Herbst 2018 musste das in Liquidation gegangene Sportmuseum Schweiz in Basel seine Tore schließen. Durch die Liquidation drohte gar der Verkauf der historisch wertvollen Sammlung: Roger Federers Racket wie auch alte Fotografien auf Glasplatten wären dann versteigert worden und in Privatsammlungen gelandet. In letzter Minute konnte ein Rettungsplan erstellt werden, sodass die Sammlung nun als Gesamtbestand erhalten bleibt und nach Biel gebracht wird. Unklar ist noch, ob und wie sie der Forschung und der breiten Öffentlichkeit zugänglich bleibt. In Privatsammlungen aber auch in Sportvereinsarchiven drohen zudem wertvolle Objekte, Akten, Fotografien durch Zerfall verloren zu gehen und das historische Wissen dazu schwindet von Generation zu Generation.

Das extreme Beispiel des Sportmuseums Schweiz ist vielleicht gar nicht so untypisch für die diskrepante Bedeutung der Sportgeschichte in der Schweiz. Bei großen Sportveranstaltungen wird in den Medien rasch auf die sportliche Tradition, die vergangenen Erfolge und die Bedeutung des Sports für die Schweiz verwiesen. Gleichzeitig ist der Sport so schnelllebig, dass sein kulturelles Erbe im Tagesgeschäft vernachlässigt wird. Es besteht gewissermaßen eine Schräglage der kulturellen Erinnerung, in mehrfacher Hinsicht: Sport war und ist immer noch männlich dominiert, entsprechend wird erinnert. Hinzu kommt ein kulturelles Erinnern, das stark auf populäre, umsatzstarke Sportarten wie Fußball, Eishockey und Skifahren fokussiert ist.

Sportgeschichte im Museum

Dies zeigt sich auch in der aktuellen Museumslandschaft der Schweiz. Während das Sportmuseum Schweiz auch zahlreiche Randsportarten und den Frauensport abdeckte, locken die beiden größten Häuser, nämlich das FIFA-Museum in Zürich und das Olympische Museum in Lausanne, mit tagesaktuellen Hauptsportarten mehrheitlich Touristen und Schulklassen an. Auffallend ist zudem bei beiden Museen, dass ein ziemlich unkritischer Umgang mit der eigenen Vergangenheit dominiert: Korruption oder die Rolle der beiden Verbände zur Zeit des Nationalsozialismus spielen kaum eine Rolle. Stark sind beide Museen in Dramaturgie und Vermitteln von Emotionen. Das FIFA-Museum setzt zudem wesentlich auf Gamification. Ein ganzes Stockwerk besteht aus einer Art Spielpalast für Jugendliche und Junggebliebene, Kinder dürfen vorgefertigte Schablonen mit ausschließlich männlichen Stars ausmalen. Digitale Vermittlungsformen spielen in beiden Sportmuseen eine zentrale Rolle, insbesondere auf interaktive Karten und bei Sportstatistik.[1]

Neue Formen der Vermittlung von Sportgeschichte

Wie andernorts in Europa wird in der Schweiz die Vermittlung von Geschichte über digitale Formen vorangetrieben. So sind in den letzten Jahren mehrere begrüßenswerte Projekte im Bereich der Public History entstanden. Eine Pionierrolle nahm im letzten Jahr das Museum des FC Zürich ein.[2] Aufgrund der Unterbelichtung des öffentlichen Erinnerns an den Frauenfußball in der Schweiz wurde ein Blog errichtet, der nach dem Prinzip des Crowdsourcing funktioniert. Ehemalige Spielerinnen bringen ihre Fotoalben und Erinnerungstücke ins Museum, diese werden digitalisiert und im Blog erläutert. Hinzu kommen Videos von Zeitzeuginnen, die aus den Anfängen des Frauenfußballs in der Schweiz berichten, beispielsweise, wie sich die Frauen gegen jegliche Widerstände und geschlechterstereotypischer Vorurteile durchkämpfen mussten. Sportgeschichte wird durch die Zeitzeuginnen erlebbar und emotional nachvollziehbar. Geplant ist zudem für 2020 eine Ausstellung zu 50 Jahre Schweizer Frauenfußball, die auch als Wanderausstellung für Schulen und Vereine konzipiert ist.

Das Swiss Sports History Digital Portal

Ein in ähnliche Richtung zielendes Projekt wurde ebenfalls letztes Jahr lanciert. Das sich im Aufbau befindende Swiss Sports History Digital Portal soll schweizweit und sprachübergreifend verschiedenen Nutzer*innengruppen den Zugang zur Sportgeschichte der Schweiz erleichtern. Ziel ist der Erhalt und die Vermittlung des historischen Erbes des Schweizer Sports. Das Portal dient der Forschung, den Medien und der schulischen Vermittlung und besteht aus drei Säulen:

– Vermittlung und Vernetzung: Ein Zeitstrahl und ein kurzes Video sollen erste Orientierung schaffen. Forschende und Medienschaffende, welche spezifisches Material, insbesondere audiovisuelle Quellen, für ihre Bereiche benötigen, erhalten hier rasch und unkompliziert Zugang zu einem breiten Fundus.

– Erschließung: Das Portal soll einerseits bestehende und neu erschlossene Quellenbestände im Netz sichtbar machen. Diese Säule bietet auch Know-how und Hilfestellungen für Vereine, welche ihr Archivgut besser aufbewahren und so ihr kulturelles Erbe künftigen Generationen zur Verfügung stellen möchten.

– Lerntools und niederschwellige Kommunikation in Schulen und Sportvereinen: Das Portal vermittelt Forschungsresultate, die aufbereitet sind, für Schulen und Sportvereine. In einer ersten Phase erfolgt dies am Thema Integration und Exklusion im Schweizer Sport. Mit einem interaktiven Online-Tool sowie dem direkten Kontakt mit Zeitzeug*innen sollen Kinder und Jugendliche dafür sensibilisiert werden, dass es nicht Zufall ist, wer wann welchen Sport betrieben hat und betreibt. Jugendliche erlernen dabei, dass die Geschichte des Sports sich nicht auf vergangene Siege und Niederlagen beschränkt.

Das an den Universitäten Luzern und Zürich angesiedelte Projekt arbeitet eng mit der Pädagogischen Hochschule Luzern und dem dortigen Institut für Geschichtsdidaktik und Erinnerungskulturen, sowie landesweit mit Museen und weiteren Gedächtnis- und Bildungsinstitutionen zusammen. Der Launch dieses Portals wird im Sommer 2019 erfolgen.

In die digitale Zukunft?

Die Zukunft wird zeigen, wie erfolgreich solche webbasierten Projekte sein werden. Die Hoffnung besteht zumindest, dass die wiedererstarkte Forschung zur Sportgeschichte in der Schweiz zu neuem Verstehen führen könnte.[3] Die Gefahren sind bekannt: Mangelnde nachhaltige Finanzierung, Vernachlässigung der bestehenden Formen der Vermittlung, vereinfachte Inhalte. Gleichwohl kann gesagt werden, dass die Digitalisierung große Chancen und Möglichkeiten bietet: Einfache Partizipation der Öffentlichkeit, Integrierbarkeit in die Lehrpläne, Erreichen neuer partizipierender Zielgruppen. Zentral scheint mir jedoch, das eine zu tun und das andere nicht zu vernachlässigen: Museen und Archive müssen weiter bestehen bleiben und öffentlich finanziert werden. Auch, weil das haptische Erlebnis der Objekte nie ersetzbar sein wird und das kulturelle Erbe des Sports auch über museale Vermittlung weiterbestehen sollte. Nicht zuletzt wird die Digitalisierung des Wissens ein Phantasma bleiben, denn sie wird nie alle Bibliotheks-, Archiv- und Museumsbereiche umfassen können. Dazu fehlen schlicht Zeit und Mittel. Die Diskrepanz zwischen medialer, ökonomischer und gegenwartsbezogener Aufmerksamkeit gegenüber dem Sport und der Vernachlässigung dessen kulturellen Erbes zeigt sich auch in der Förderpolitik des Bundesamtes für Kultur: Sportgeschichte spielte im Kulturerbejahr 2018 keine Rolle.[4] Das wird sich künftig hoffentlich ändern.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Jucker, Michael et al., eds. Masse, Märkte und Macht in der Geschichte des Sports. Zürich: Chronos, 2016.

- Haxal, Daniel, “The National Football Museum and the FIFA World Football Museum,” Journal of Sporthistory 45, no. 1 (2018): 96-98.

- Gautschi, Peter. “Gamification as a Miracle Cure for Public History?,” Public History Weekly 6, no. 37 (2018). dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-13011.

Webressourcen

- Projektwebsite des Vermittlungsprojekts: https://www.sportshistory.ch (letzter Zugriff am 15. Januar 2019).

- Blog des FC Zürich-Museums zum Frauenfussball: https://seit1968.ch (letzter Zugriff am 15. Januar 2019).

- Sportmuseum Schweiz: https://www.sportmuseum.ch (letzter Zugriff am 15. Januar 2019)

_____________________

[1] Daniel Haxal, “The National Football Museum and the FIFA World Football Museum,” Journal of Sport History 45, no. 1 (2018): 96-98. Robert Kossuth and Carly Adams, “Reflections on Critical Sport History in the Museum: Opportunities and Challenges from a Local/Regional Project,” Journal of Sport History 40, no. 2 (2013): 285-295.

[2] Siehe die Webressourcen. Beide Projekte kooperieren auch mit dem Verein für Schweizer Sportgeschichte, www.sportshistory.ch (letzter Zugriff 15. Januar 2019). Weitere Vermittlungsprojekte von Wissenschaftsinhalten finden sich auf https://www.science-et-cite.ch/de und https://www.grstiftung.ch/de/handlungsfelder/scientainment.html (letzter Zugriff 15. Januar 2019).

[3] Martin Crotty, “Sport, Popular Culture, and the Future: Some Commentary,” Journal of Sport History 40, no. 1 (2013): 57-67. Zur neueren Forschung in der Schweiz siehe demnächst: Thomas Busset, Christian Koller, und Michael Jucker, eds., Nouvelles recherches sur l’histoire du sport en Suisse (Neuchâtel: Editions CIES, 2019) in print, see also: Grégory Quin, “Writing Swiss Sport History: A Quest for Original Archives,” The International Journal of the History of Sport 34, no. 5-6 (2017): 432-436.

[4] Siehe https://kulturerbefueralle.ch (letzter Zugriff 15. Januar 2019).

_____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

Näfelser Schwingfest, undatiert © ETH Zürich e-pics

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Jucker, Michael: Sportgeschichte als bedrohte Public History. In: Public History Weekly 7 (2019) 4, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-13304.

Copyright (c) 2019 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 7 (2019) 4

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2019-13304

Tags: Digital Change (Digitaler Wandel), Museum, Sport History (Sportgeschichte), Switzerland (Schweiz)