Abstract: Food is universal, popular and familiar. Despite these adjectives, food remains an isolated topic in academic scholarship. However, in 2012, The Public Historian (the leading public history journal) had a whole issue on food and public history.[1] The public history focus stems from both the rich food’s potential to connect historians and the public as well as the fantastic sets of sources and questions – diets, culinary instruments, agricultural and industrial production, and behavior – that can be studied. I posit that food, in its complexity, can, not only be a source for historians, but is actually very much symbolic of the development of public history. Public history of food encompasses new interests in everyday life, family history, local memories, participatory model, and visitors’ wish to experience the past.

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-11546

Languages: English, Francais, Deutsch

Food is universal, popular and familiar. Despite these adjectives, food remains an isolated topic in academic scholarship. However, in 2012, The Public Historian (the leading public history journal) had a whole issue on food and public history.[1] The public history focus stems from both the rich food’s potential to connect historians and the public as well as the fantastic sets of sources and questions – diets, culinary instruments, agricultural and industrial production, and behavior – that can be studied. I posit that food, in its complexity, can, not only be a source for historians, but is actually very much symbolic of the development of public history. Public history of food encompasses new interests in everyday life, family history, local memories, participatory model, and visitors’ wish to experience the past.

Everyday Life and Primary Sources

Pillar of living history interpretation since the 1930s, food is not a new topic for historians.[2] Nonetheless, the relations between food and historical narratives were affected by more recent and broader shifts in historiography. Through social and oral practices, historians have, since the 1960s, paid increasing attention to ordinary people. A focus on everyday life has opened up a brand-new range of topics for (public) historians, including but not limited to, shopping and consumption, housing, health, criminality, poverty, and food. Alongside this trend, food history has also benefited from the rise of family history – from which genealogy is a widespread example – as a popular but also increasingly as an academic and now marketing interest.

As demonstrated by Rosenzweig and Thelen, family is the main vector for Americans to understand and access their past, so the historians’ interest in everyday life and family would only be a natural reconnection with the public.[3] Symbolized by family cookbooks, food can be a very powerful and popular practice to preserve family memories. A focus on food contributes to a plurality of historical studies on technology, agriculture, housekeeping, domestic tasks, and living conditions. Cathy Stanton and Michelle Moon detail, for instance, how the study of recipes can help understand the impact of “domestic science” and dietary reforms since the 1960s in which women gained additional training and power.[4] Food is a wonderful medium because it can connect historians with large audiences and symbolize a global shift in historiography that leaves more space to ordinary people.

Sites, Food and Audiences

New interest in food history also derives from new practices within cultural institutions. Wishing to attract and diversify their audiences, some institutions have explored new projects. Related to the overall public history movement, many cultural institutions have, since the 1980s, developed visitor experiences and public participation. Food can be an incredible hook to connect visitors to the past. Megan Elias has used food – and smell – to connect visitors to the period rooms and neighboring stores of the Tenement Museum in New York City.[5] Period kitchens with costume interpreters in historic sites have proposed to experience the past through food. For instance, costume interpreters prepare historical dishes at Governor’s Palace kitchen at Colonial Williamsburg (Virginia, USA). In many sites, visitors can actually participate in culinary activities, giving them another layer of experience.

The Internet and digital technology have developed public participation. Some food history projects rely on crowdsourcing and co-creation. The New York Public library developed “What’s on the Menu?” that asks people to help transcribe the corpus of historical restaurant menus, dish by dish. In early March 2018, users had transcribed 17,545 menus and 1,333,403 dishes that can be used by “historians, chefs, novelists and everyday food enthusiasts”. It would be very interesting to evaluate the impact of that project on current food uses.

History, Activism and the Environment

In spite of this renewed interest from cultural institutions, food is too often simply considered a “hook to attract audiences and redirect their interest to other interpretive messages deemed more significant”.[6] This may result in the history of food merely contributing to nostalgia and/or celebrating a romantic vision of the past. Some sites have critically explored the relations between food and socio-cultural changes. For instance, in 2012, the American Museum of Natural History displayed “Our Global Kitchen: Food, Nature, Culture” while the American Museum of National History proposed “Food: Transforming the American Table, 1950-2000”. In 2017, this latter museum hired a “brewing historian”. Theresa McCulla works as historian to oversee the American Brewing History Initiative, part of the Food History program. Interestingly, McCulla has both a doctorate in American Studies as well as a culinary arts diploma from a Professional Chefs Program, showing the need for public history practitioners to diversify their skills.

From Food to Communities

I was recently invited to talk about public history and culinary heritage in Canada and I was amazed by the variety of interlocutors – local historians, cooks, but also biologists, nutritionists, farmers, and marketing companies – that such a topic can bring together. Public history of food can also connect to environmental policy, but also actors of the green revolution, the slow food movement, and regional foodscapes. The slow food movement as well as public-supported brands such as AOC (Controlled Name of Origin) in France are based on a revival of local identity for which historians can contribute by giving historical methodology. Historians can connect local food-based movements with broader understanding of the past that include the history of the food system – farming, environment, food-industry, transportation, consumption, and policy – as well as historic sites and institutions. This glocal approach is, Serge Noiret and I argue, a crucial dimension of international public history.[7] For instance, a glocal approach of food and technology would be the study the relation between the evolution of one local dish in connection with the broader impact of the invention and spread of refrigerator on local cooking, housework, and preservation practices.

Finally, food can help connecting teaching practices with wider audiences. My current students organize an exhibition on the history of immigration in Colorado using recipes as primary sources.[8] In addition to migrations, recipes and dishes show, through their evolution and adaptation to new environments, how immigrants have both participated in local foodscape as well as integrated to their new communities. Recipes come from the public, attract new audiences, and allow new historical interpretation, plenty of reasons to support the idea that food may be a symbol of the development of public history.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Moon, Michelle, and Cathy Stanton. Public History and the Food Movement: Adding the Missing Ingredient. New York/London: Routledge, 2017.

- Gardner, James, and Paula Hamilton eds. Oxford Handbook of Public History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Web Resources

- New York Public Library “What’s on the Menu?” www.menus.newyorkpubliclibrary.org/about (last accessed 8 March 2018).

- National Museum of American History “Smithsonian Hires Scholar to Document Brewing History” January 2017, www.americanhistory.edu/brewing-history (last accessed 8 March 2018).

- Sainte Anne University “Qu’est ce qu’on mange?” Workshop on Food and Public History, March 8, 2018, www.youtube.com/Patrimoine_culinaire_et_mémoire_culturelle (last accessed 8 March 2018).

_____________________

[1] The Public Historian 34, no. 2, (2012).

[2] Michelle Moon and Cathy Stanton, Public History and the Food Movement: Adding the Missing Ingredient (New York/London: Routledge, 2017), 111.

[3] Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen, The Presence of the Past. Popular Uses of History in American Life (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998).

[4] Michelle Moon and Cathy Stanton, Public History and the Food Movement: Adding the Missing Ingredient (New York/London: Routledge, 2017), 25.

[5] Megan Elias, “Summoning the Food Ghosts: Food History as Public History,” The Public Historian 34, no. 2 (2012): 13-29.

[6] Cathy Stanton, “Between Pastness and Presentism: Public History and Local Food Activism,” in James Gardner and Paula Hamilton (eds.), Oxford Handbook of Public History, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017: 225

[7] Thomas Cauvin and Serge Noiret, “Internationalizing Public History” in Oxford Handbook of Public History, eds.James Gardner and Paula Hamilton (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).

[8] CSU Graduate Students, “Bags Packed and Headed to the Rockies: Fort Collins and the Legacy of Immigration”, Facebook page, www.facebook.com/Bags-Packed-and-Headed-to-the-Rockies (last accessed 9 March 2018).

_____________________

Image Credits

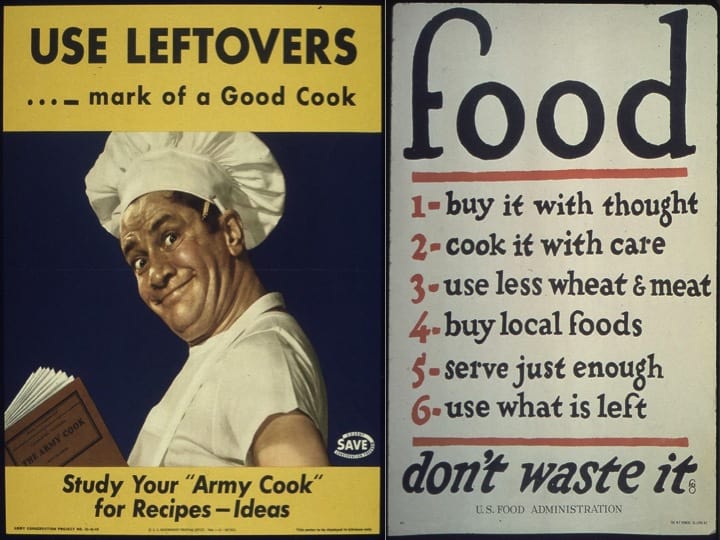

Photomontage „Food, a central issue in history“. Left Image: “USE LEFTOVERS – MARK OF A GOOD COOK – STUDY YOUR ‘ARMY COOK’ FOR RECIPES, IDEAS” © Office for Emergency Management. Office of War Information. Domestic Operations Branch. Bureau of Special Services (9 March 1943 – 15 September 1945). www.commons.wikimedia.org, public domain (last accessed 17 March 2018). Right Image: “Food. 1-buy it with thought, 2-cook it with care, 3-use less wheat and meat, 4-buy local foods, 5-serve just enough, 6- use what is left. Don’t waste it.” © U.S. Food Administration. Educational Division. Advertising Section. (15 January 1918 – January 1919). www.commons.wikimedia.org, public domain (last accessed 17 March 2018).

Recommended Citation

Cauvin, Thomas: Bon Appétit: Food and Public History. In: Public History Weekly 6 (2018) 14, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-11546

La cuisine est un élément universel, populaire, et familier. Pour autant et malgré de belles exceptions, elle reste un sujet trop peu étudié dans les milieux académiques. Toutefois, en 2012, The Public Historian, la principale revue d’histoire publique outre-Atlantique, a dédié un numéro complet à la nourriture.[1] Les liens entre l’histoire publique et le patrimoine culinaire proviennent des multiples sources pour l’historien tels que les plats, les instruments de cuisine, l’agriculture et l’industrie, et les savoir-faire. La cuisine, dans sa complexité, n’est pas simplement une source pour l’historien, mais est aussi le symbole de l’essor de l’histoire publique. Une histoire publique et culinaire met en avant les études de la vie quotidienne, des familles, des mémoires locales, tout autant qu’une construction participative de l’histoire et une demande d’expérience de la part des visiteurs.

Vie quotidienne et Archives

Elément majeur de la naissance des sites d’interprétation scandinaves des années 1930, le patrimoine culinaire n’est pas un nouveau sujet pour l’historien.[2] Toutefois, les relations entre la nourriture et les discours historiques ont fondamentalement changé par l’intermédiaire de nouveaux courants historiographiques. Par exemple, l’histoire orale et l’histoire sociale ont, depuis les années 1960, donné plus d’importance à la vie quotidienne. Cette dernière pouvait comprendre des sujets tels que la culture de consommation, le logement, la santé et l’hygiène, la pauvreté, et aussi la nourriture. Les études du patrimoine culinaire ont aussi bénéficié du regain d’intérêt pour l’histoire familiale à la fois comme sujet de recherche – pensons ici à la généalogie – et comme vecteur de savoir. Comme l’ont très bien montré Rosenzweig et Thelen, la famille est le principal vecteur d’accès au passé pour les Américains.[3] Symbolisé par les livres de recettes familiales, le patrimoine culinaire peut être un des modes de compréhension de l’histoire familiale. En outre, l’histoire de la cuisine peut renseigner sur des domaines adjacents comme la technologie, l’agriculture, les tâches domestiques, et les conditions de vie. Cathy Stanton et Michelle Moon expliquent comment l’étude des recettes de cuisine peut aider à mieux comprendre les changements d’activités des femmes au foyer en lien avec la “science domestique” et les réformes diététiques depuis les années 1960.[4] La cuisine est un formidable medium pour relier les historiens à un public plus large et symbolise un changement historiographique plus global qui bouleverse les pratiques.

Lieux, Cuisine et Public

L’intérêt pour la cuisine et le patrimoine culinaire est également lié à de nouvelles pratiques au sein des institutions culturelles. Dans le but d’attirer de nouvelles audiences, certaines institutions se sont, depuis au moins les années 1980, concentrées sur les expériences et la participation du public. La cuisine peut service d’accroche pour connecter les visiteurs au passé. Megan Elias a ainsi utilisé la cuisine – et les senteurs – pour enrichir les discours historiques du Tenement Museum à New York.[5] Des cuisines avec des interprètes en costume proposent aux visiteurs de revivre le passé à travers la préparation de certains plats. Par exemple, des figurants préparent des plats historiques au Palais du Gouverneur à Colonial Williamsburg (Virginie, États-Unis). Dans certains sites, le public peut aussi participer aux activités culinaires et contribuer à l’interprétation du passé. Le développement de l’internet a aussi contribué à la participation du public – au travers du crowdsourcing et de la création partagée. La bibliothèque publique de New York a créé “Qu’y a-t-il au menu ?”, un projet qui demande au public d’aider à la transcription d’un corpus historique de menus de restaurants de la ville, plat par plat. En mars 2018, le public avait aidé à transcrire plus de 17 000 menus et 1 333 400 plats qui peuvent être utilisés par “des historiens, des cuisiniers, des romanciers, et des amateurs de cuisine”. Il serait très intéressant de pouvoir analyser l’impact éventuel de ce projet sur les pratiques culinaires des utilisateurs.

Histoire, Activisme et Environnement

Malgré un regain d’intérêt auprès de certaines institutions culturelles, la cuisine est trop souvent considérée comme un simple “moyen d’attirer le public et de le rediriger vers d’autres sujets jugés plus important”.[6] Cela contribue à une histoire du patrimoine culinaire soit nostalgique soit glorifiant une vision romantique du passé. D’autres sites se sont lancés dans une étude critique des relations entre nourriture et changements socio-culturels. En 2012 par exemple, le Musée Américain d’Histoire Naturelle a organisé “Notre Cuisine Globale: Nourriture, Nature, Culture” pendant que le Musée Américain d’Histoire Nationale proposait “Nourriture: Transformations de la Cuisine Américaine, 1950-2000”. En 2017, ce dernier musée a engagé une “historienne de la bière”. Theresa McCulla travaille ainsi comme historienne en charge du Projet de l’Histoire Américaine de la Bière. Il est intéressant de noté que McCulla possède à la fois un doctorat d’Études Américaines et un diplôme des arts culinaires, démontrant l’intérêt d’une diversification des compétences de l’historien public.

De la cuisine aux communautés

Je fus récemment invité au Canada pour parler d’histoire publique et de patrimoine culinaire, et je fus surpris de la variété des interlocuteurs – historiens amateurs, cuisiniers, biologistes, nutritionnistes, agriculteurs, et compagnies privées – qu’un tel sujet pouvait rassembler. L’histoire publique du patrimoine culinaire peut être faite en lien avec les politiques environnementales, des partisans de la révolution verte, du mouvement slow-food, et du terroir. Le mouvement slow-food ainsi que les acteurs des marques déposées – comme les AOCs en France – sont portés en partie par une volonté de défendre une identité locale. Les historiens peuvent, grâce à leur approche critique, relier les acteurs de ces mouvements à une compréhension plus historique et plus globales du passé, notamment en incluant l’histoire des multiples acteurs de la production – agriculteurs, industrie agro-alimentaire, transporteurs, consommateurs, et politiques – et les espaces de production. L’approche “glocale” est, comme je le propose avec Serge Noiret, une dimension très importante de l’histoire publique internationale.[7] Par exemple, une approche “glocale” de la cuisine et de la technologie pourrait relier l’évolution de certains plats, des pratiques culinaires, des tâches domestiques, avec le développement de l’utilisation du réfrigérateur dans les foyers.

Enfin, l’étude des pratiques et du patrimoine culinaires peut permettre de connecter la pédagogie avec un public plus large. Ce semestre, mes étudiants organisent une exposition sur l’histoire de l’immigration au Colorado grâce à des recettes de cuisine.[8] Outre les migrations, les plats et les recettes démontrent, au travers leur évolution et leur adaptation à de nouveaux environnements, en quoi les migrants ont participé aux patrimoines culinaires locaux. Les recettes proviennent du public, attirent de nouveaux acteurs, et permettent de nouvelles interprétations historiques, bon nombre de raisons qui justifient l’idée que la cuisine peut être un symbole du développement de l’histoire publique.

_____________________

Lectures supplémentaires

- Moon, Michelle, and Cathy Stanton. Public History and the Food Movement: Adding the Missing Ingredient. New York/London: Routledge, 2017.

- Gardner, James, and Paula Hamilton eds. Oxford Handbook of Public History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Resources sur le web

- New York Public Library “What’s on the Menu?” www.menus.newyorkpubliclibrary.org/about (dernier accès le 8 mars 2018).

- National Museum of American History “Smithsonian Hires Scholar to Document Brewing History” January 2017, www.americanhistory.edu/brewing-history (dernier accès le 8 mars 2018).

- Sainte Anne University “Qu’est ce qu’on mange?” Workshop on Food and Public History, March 8, 2018, www.youtube.com/Patrimoine_culinaire_et_mémoire_culturelle (dernier accès le 8 mars 2018).

_____________________

[1] The Public Historian 34, no. 2, (2012).

[2] Michelle Moon and Cathy Stanton, Public History and the Food Movement: Adding the Missing Ingredient (New York/London: Routledge, 2017), 111.

[3] Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen, The Presence of the Past. Popular Uses of History in American Life (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998).

[4] Michelle Moon and Cathy Stanton, Public History and the Food Movement: Adding the Missing Ingredient (New York/London: Routledge, 2017), 25.

[5] Megan Elias, “Summoning the Food Ghosts: Food History as Public History,” The Public Historian 34, no. 2 (2012): 13-29.

[6] Cathy Stanton, “Between Pastness and Presentism: Public History and Local Food Activism,” in James Gardner and Paula Hamilton (eds.), Oxford Handbook of Public History, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017: 225

[7] Thomas Cauvin and Serge Noiret, “Internationalizing Public History” in Oxford Handbook of Public History, eds.James Gardner and Paula Hamilton( Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).

[8] CSU Graduate Students, “Bags Packed and Headed to the Rockies: Fort Collins and the Legacy of Immigration”, Facebook page, www.facebook.com/Bags-Packed-and-Headed-to-the-Rockies (dernier accès le 8 mars 2018).

_____________________

Crédits illustration

Photomontage „Food, a central issue in history“. Image de gauche: “USE LEFTOVERS – MARK OF A GOOD COOK – STUDY YOUR ‘ARMY COOK’ FOR RECIPES, IDEAS” © Office for Emergency Management. Office of War Information. Domestic Operations Branch. Bureau of Special Services (9 March 1943 – 15 September 1945). www.commons.wikimedia.org, public domain (dernier accès le 8 mars 2018). Image de droite: “Food. 1-buy it with thought, 2-cook it with care, 3-use less wheat and meat, 4-buy local foods, 5-serve just enough, 6- use what is left. Don’t waste it.” © U.S. Food Administration. Educational Division. Advertising Section. (15 January 1918 – January 1919). www.commons.wikimedia.org, public domain (dernier accès le 8 mars 2018).

Citation recommandée

Cauvin, Thomas: Bon Appétit: Cuisine et Histoire Publique. In: Public History Weekly 6 (2018) 14, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-11546

Essen ist universell, beliebt und vertraut. Trotz dieser positiven Zuschreibungen bleibt Essen ein isoliertes Thema in der Wissenschaft. Doch im Jahr 2012 widmete ‘The Public Historian’ eine ganze Ausgabe dem Essen und den Lebensmitteln.[1] Public History profitiert bei der Thematisierung von Essen und Lebensmitteln sowohl vom Potential, mit diesem Thema Wissenschaft und Öffentlichkeit zu verbinden, als auch von den fantastischen Quellen und Fragen – Ernährung, kulinarische Instrumente, landwirtschaftliche und industrielle Produktion und Verhalten – die untersucht werden können. Ich gehe davon aus, dass Essen und Lebensmittel in ihrer Komplexität nicht nur eine Quelle für HistorikerInnen sein können, sondern heute auch symbolisch aufzeigen, wie sich Public History entwickelt. Public History zum Thema Essen und Lebensmittel verdeutlicht neues Interesse für Alltag, Familiengeschichte, lokale Erinnerungen, partizipatives Modell und den Wunsch, Vergangenheit zu erleben.

Alltag und primäre Quellen

Das Thema Essen ist seit den 1930er Jahren zentraler Bestandteil von Alltagsgeschichte und also auch kein neues Thema für HistorikerInnen.[2] Gleichwohl wurden die Beziehungen zwischen Essen und historischen Erzählungen durch neuere und breitere Verschiebungen in der Geschichtswissenschaft beeinflusst. Durch soziale und mündliche Praktiken haben HistorikerInnen seit den 1960er Jahren den gewöhnlichen Menschen immer mehr Aufmerksamkeit geschenkt. Die Fokussierung auf das Alltagsleben hat den HistorikerInnen und den Public Historians ein völlig neues Themenspektrum eröffnet, das unter anderem Einkaufen und Konsumieren, Wohnen, Gesundheit, Kriminalität, Armut und Ernährung umfasst. Neben diesem Trend profitiert die Geschichte zum Essen und den Lebensmitteln auch vom Aufstieg der Familiengeschichte – zu der die Genealogie ein weit verbreitetes Beispiel ist – und zwar sowohl im Bereich der Geschichtswissenschaften als auch in der Public History oder im Marketing.

Wie Rosenzweig und Thelen zeigen, ist die Familie für die AmerikanerInnen der hauptsächliche Türöffner, um ihre Vergangenheit zu verstehen und darauf zuzugreifen, sodass das Interesse der HistorikerInnen an Alltag und Familie ein naheliegender Weg ist, um sich mit der Öffentlichkeit zu verbinden.[3] Durch Familienkochbücher symbolisiert, kann Essen eine sehr mächtige und beliebte Praxis sein, um Familienerinnerungen zu bewahren. Eine Fokussierung auf Essen und Lebensmittel trägt zu einer Vielzahl von historischen Studien über Technik, Landwirtschaft, Hauswirtschaft, häusliche Aufgaben und Lebensbedingungen bei. Cathy Stanton und Michelle Moon erläutern zum Beispiel, wie das Studium von Rezepten dazu beitragen kann, die Auswirkungen von “Hauswirtschaft” und Ernährungsreformen seit den 1960er Jahren zu verstehen, in denen Frauen zusätzliche Ausbildung und Macht erhielten. Essen ist ein wunderbares Medium, weil es erstens HistorikerInnen mit einem grossen Publikum verbinden kann und weil zweitens dadurch ein globaler Wandel in der Geschichtsschreibung verdeutlicht wird, der gewöhnlichen Menschen mehr Aufmerksamkeit zukommen lässt.

Standorte, Essen und Publikum

Neues Interesse an Essens- und Lebensmittelgeschichte ergibt sich auch aus neuen Praktiken innerhalb von Kultureinrichtungen. Im Wunsch, mehr und vielfältigeres Publikum anzuziehen, haben einige Institutionen neue Projekte lanciert. Mit Blick auf die gesamte öffentliche Geschichtsbewegung haben viele Kultureinrichtungen seit den 1980er Jahren darauf hingearbeitet, BesucherInnen neue Erfahrungen zu ermöglichen und sie zu aktivieren. Essen kann eine sehr gute Möglichkeit sein, um BesucherInnen mit der Vergangenheit in Verbindung zu bringen. Megan Elias hat Essen, Lebensmittel und Gerüche verwendet, um die BesucherInnen mit den historischen Räumen und den benachbarten Geschäften des Tenement Museums in New York City zu verbinden.[5] Zeitgenössische Küchen mit DarstellerInnen in historischen Kostümen an historischen Orten laden ein, Vergangenheit durch Essen zu erleben. So bereiten zum Beispiel DarstellerInnen in historischen Kostümen historische Gerichte in der Küche des Governor’s Palace in Colonial Williamsburg (Virginia, USA) zu. An vielen weiteren Orten können BesucherInnen an kulinarischen Aktivitäten teilnehmen, was ihnen eine neue Dimension des Erlebens bietet.

Auch haben das Internet und digitale Technologien die Öffentlichkeit zusätzlich aktiviert. Einige lebensmittelgeschichtliche Projekte sind auf Crowdsourcing und Zusammenarbeit angewiesen. Die New York Public Library entwickelte das Projekt “What’s on the Menu?”, bei dem die NutzerInnen aufgefordert werden, den Bestand der Menukarten historischer Restaurants zu transkribieren, Gericht für Gericht. Anfang März 2018 hatten die NutzerInnen 17.545 Menüs und 1.333.403 Gerichte transkribiert, die von “HistorikerInnen, KöchInnen, SchriftstellerInnen und LiebhaberInnen des täglichen Essens” verwendet werden können. Es wäre sehr interessant, die Auswirkungen dieses Projekts auf die derzeitige Verwendung von Lebensmitteln zu untersuchen.

Geschichte, Aktivismus und Umwelt

Trotz dieses erneuten Interesses von Kulturinstitutionen wird Essen allzu oft einfach als “Haken betrachtet, um das Publikum anzuziehen und sein Interesse auf andere Themen zu lenken, die als wichtiger erachtet werden”.[6] Dies kann dazu führen, dass die Geschichte des Essens lediglich zur Nostalgie beiträgt und/oder eine romantische Vision der Vergangenheit feiert. Einige AkteurInnen haben sich jedoch kritisch mit den Zusammenhängen zwischen Ernährung und soziokulturellen Veränderungen auseinandergesetzt. So zeigte das American Museum of Natural History 2012 die Ausstellung “Unsere globale Küche: Lebensmittel, Natur, Kultur”, und das American Museum of National History zeigte “Lebensmittel: die Veränderung des amerikanischen Angebots, 1950-2000”. Im Jahr 2017 stellte dieses Museum eine “Brauhistorikerin” ein. Theresa McCulla arbeitet als Historikerin für die American Brewing History Initiative, die Teil des Food History Programms ist. Interessanterweise hat McCulla sowohl einen Doktortitel in Amerikanistik als auch ein Diplom einer professionellen Kochausbildung, was die Notwendigkeit zeigt, dass PraktikerInnen der Public History ihre Fähigkeiten diversifizieren müssen.

Vom Essen zur Gemeinschaft

Vor kurzem wurde ich eingeladen, um über die öffentliche Geschichte und das kulinarische Erbe in Kanada zu sprechen, und ich war erstaunt über die Vielfalt der GesprächspartnerInnen – lokale HistorikerInnen, KöchInnen, aber auch BiologInnen, ErnährungswissenschaftlerInnen, LandwirtInnen und Marketingfirmen – die ein solches Thema zusammenbringen kann. Public History zu Essen und Lebensmitteln kann auch mit der Umweltpolitik in Verbindung gebracht werden, ebenso mit den AkteurInnen der Grünen Revolution, der Slow-Food-Bewegung und den VertreterInnnen regionaler Produkte. Die Slow-Food-Bewegung sowie öffentlich unterstützte Marken wie AOC (geschützte Herkunftsbezeichnung) in Frankreich basieren auf einer Wiederbelebung der lokalen Identität, zu der HistorikerInnen mit historischer Methodologie beitragen können. HistorikerInnen können lokale Lebensmittelbewegungen mit einem breiteren Verständnis der Vergangenheit unterstützen, das die Geschichte des Ernährungssystems – Landwirtschaft, Umwelt, Lebensmittelindustrie, Transport, Konsum und Politik – sowie historische Stätten und Institutionen umfasst. Dieser “glokale” Ansatz ist, so argumentieren Serge Noiret und ich, eine entscheidende Dimension der internationalen Public History. Ein “glokaler” Ansatz bezüglich Nahrung und Lebensmittel-Technologie wäre zum Beispiel die Untersuchung des Zusammenhangs zwischen der Entwicklung eines lokalen Gerichts mit dem Einfluss der Erfindung und Verbreitung des Kühlschranks auf die lokale Küche, die Hausarbeit und die Konservierungspraktiken.

Schliesslich kann die geschichtliche Thematisierung von Essen und Lebensmitteln helfen, Geschichte einem breiteren Publikum zu vermitteln. Meine derzeitigen Studierenden organisieren eine Ausstellung über die Geschichte der Einwanderung in Colorado unter Verwendung von Rezepten als Hauptquellen. Neben den Migrationen zeigen Rezepte und Gerichte durch ihre Entwicklung und Anpassung an neue Umgebungen, wie EinwandererInnen sowohl die lokale Ernährungslandschaft geprägt haben als auch von ihr geprägt wurden. Rezepte kommen aus der Öffentlichkeit, ziehen ein neues Publikum an und erlauben neue historische Interpretationen – wirklich viele Gründe, um die Idee zu unterstützen, dass der geschichtliche Umgang mit Essen und Lebensmittel ein Symbol für die Entwicklung von Public History ist.

_____________________

Literaturhinweise

- Moon, Michelle, and Cathy Stanton. Public History and the Food Movement: Adding the Missing Ingredient. New York/London: Routledge, 2017.

- Gardner, James, and Paula Hamilton eds. Oxford Handbook of Public History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Webressourcen

- New York Public Library “What’s on the Menu?” www.menus.newyorkpubliclibrary.org/about (letzter Zugriff 8.3.2018).

- National Museum of American History “Smithsonian Hires Scholar to Document Brewing History” January 2017, www.americanhistory.edu/brewing-history (letzter Zugriff 8.3.2018).

- Sainte Anne University “Qu’est ce qu’on mange?” Workshop on Food and Public History, March 8, 2018, www.youtube.com/Patrimoine_culinaire_et_mémoire_culturelle (letzter Zugriff 8.3.2018).

_____________________

[1] The Public Historian 34, no. 2, (2012).

[2] Michelle Moon and Cathy Stanton, Public History and the Food Movement: Adding the Missing Ingredient (New York/London: Routledge, 2017), 111.

[3] Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen, The Presence of the Past. Popular Uses of History in American Life (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998).

[4] Michelle Moon and Cathy Stanton, Public History and the Food Movement: Adding the Missing Ingredient (New York/London: Routledge, 2017), 25.

[5] Megan Elias, “Summoning the Food Ghosts: Food History as Public History,” The Public Historian 34, no. 2 (2012): 13-29.

[6] Cathy Stanton, “Between Pastness and Presentism: Public History and Local Food Activism,” in James Gardner and Paula Hamilton (eds.), Oxford Handbook of Public History, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017: 225

[7] Thomas Cauvin and Serge Noiret, “Internationalizing Public History” in Oxford Handbook of Public History, eds.James Gardner and Paula Hamilton( Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).

[8] CSU Graduate Students, “Bags Packed and Headed to the Rockies: Fort Collins and the Legacy of Immigration”, Facebook page, www.facebook.com/Bags-Packed-and-Headed-to-the-Rockies (letzter Zugriff 8.3.2018).

____________________

Abbildungsnachweis

Fotomontage „Food, a central issue in history“. Linke Abbildung: “USE LEFTOVERS – MARK OF A GOOD COOK – STUDY YOUR ‘ARMY COOK’ FOR RECIPES, IDEAS” © Office for Emergency Management. Office of War Information. Domestic Operations Branch. Bureau of Special Services (9 March 1943 – 15 September 1945). www.commons.wikimedia.org, public domain (letzter Zugriff 17.3.2018). Rechte Abbildung: “Food. 1-buy it with thought, 2-cook it with care, 3-use less wheat and meat, 4-buy local foods, 5-serve just enough, 6- use what is left. Don’t waste it.” © U.S. Food Administration. Educational Division. Advertising Section. (15 January 1918 – January 1919). www.commons.wikimedia.org, public domain (letzter Zugriff 17.3.2018).

Übersetzung

Empfohlene Zitierweise

Cauvin, Thomas: Bon Appétit: Essen und Public History. In: Public History Weekly 6 (2018) 14, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-11546

Copyright (c) 2018 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 6 (2018) 14

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2018-11757

Tags: Food History (Geschichte des Essens), Glocal Public History, Language: French, Nostalgia (Nostalgie)