Abstract:

A statement frequently heard in everyday conversations in Colombia and in the country’s local media is that this is “a violent country by nature.” The violent 16th-century conquest or the numerous civil wars in the 19th century are recounted time and again as stages of a long and continuous history of violence, of which the half-century long armed conflict is simply one more phase. Has this recent past fashioned our expectations of the future and also our past? Do we historians have any responsibility in the naturalization of violence? And if so, what might we do from a public history perspective?

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-18867

Languages: English, Spanish

Escribiendo desde Colombia, un país que se encuentra en una coyuntura desesperanzadora, la autora nos invita a pensar cómo la imaginación histórica puede ayudarnos a salir del tiempo-trauma de las narrativas de permanente violencia y contribuir en la formación de una sociedad que pueda pensar un futuro por fuera de la guerra.

Violencia como pasado y como destino

Una de las premisas sobre las que se funda la historia como disciplina es la critica a la imposición de preocupaciones, intereses y valores del presente en los actores del pasado. Desde hace unas décadas, sin embargo, la relación del historiador con el presente se ha complejizado y lo que denominamos “presentismo,” ha dejado de ser un pecado y se ha convertido en un campo en disputa. Existe hoy entre los historiadores un consenso generalizado acerca de que cierto presentismo es inescapable, pues el pasado no es una realidad objetiva susceptible de ser interpretada en sus propios términos.[1] Pero además, si no hubiera motivaciones presentistas ¿que sería de la historia desde abajo, los estudios feministas y postcoloniales y, por supuesto, de la historia pública?

Sin embargo, convertir el pasado remoto en espejo del presente, es otra cosa. En el caso colombiano puede ser una forma quizás inevitable, pero también peligrosa, de lidiar con los dolores de una guerra de más de medio siglo. Las narraciones que escuchamos a menudo en los medios, el cine, o las conversaciones cotidianas, deshistorizan la violencia en Colombia al construir pasados coloniales o republicanos como mitos de origen de un violento presente aparentemente inescapable. Según François Hartog, este tiempo-presentista es siempre tiempo-trauma. Es el tiempo de un presente omnipresente, que clausura el futuro y en el que el pasado no termina de pasar.[2] Es un tiempo que nos impide desentrañar otros posibles pasados, y con ellos, imaginar posibles futuros.

Apoyados en las teorías de la modernización, el desarrollo, o la dependencia, numerosos historiadores en América Latina construyeron, durante la segunda mitad del siglo XX, un pasado que, ya fuera por la imposición de instituciones españolas, las constantes guerras civiles en el siglo XIX, o una economía dependiente, solo podía anteceder o explicar el considerado atraso de la región. Aunque por motivaciones distintas, no poca de la historia narrada y escrita sobre la violencia contemporánea ha construido pasados remotos inexplicables por fuera de esta narrativa comprensiva de la violencia. Hace solo unos meses un reconocido historiador publicó un libro sobre los argumentos que han justificado el uso de la violencia en Colombia. En una entrevista dijo: “En la Conquista era lícito matar indios. En la Colonia, la violencia contra los rebeldes era permitida. En la Independencia era válida para reemplazar al tirano, y en el siglo XIX, para eliminar al enemigo político. En los últimos sesenta años se la ha defendido como legítima para destruir un régimen opresivo y, en respuesta, para defenderse de la respuesta subversiva.”[3] Un libro histórico sobre la justificación del uso de la violencia a través del tiempo es fundamental, sin duda, y el alcance, las preguntas y las fuentes de este libro son particularmente notables.

En la introducción el autor explica además que las violencias presentes “no son simples prolongaciones del pasado” como argumentó por mucho tiempo la historiografía nacional. Sin embargo, en una entrevista que llega a públicos amplios, la violencia se presenta como característica inescapable en la historia de Colombia. La conquista por supuesto fue violenta, pero no solo en lo que hoy es Colombia, sino en toda la América española. Los españoles justificaron el uso de la violencia de la misma manera a lo largo de todo el territorio conquistado. Las guerras civiles tras las independencias sacudieron a la gran mayoría de nuevas Repúblicas y el derecho de rebelión fue invocado en general por todos los alzados en armas. Los intentos de paz fueron también constantes en todas las Repúblicas a lo largo del mismo siglo, aunque se hayan estudiado mucho menos que la guerra. Según el mismo historiador, “esta realidad” siempre violenta, “ha creado en los colombianos, independientemente de la corriente ideológica a la que pertenezcan, el imaginario de que la violencia es legítima cuando se utiliza para someter a los enemigos políticos.” ¿Pero no es, más bien, esta caracterización de nuestra historia la que ha creado, en alguna medida, este imaginario?

Antropólogos e historiadores han estudiado cómo lo que aprendemos del pasado, así como lo que recordamos y los recuerdos que transmitimos, constituyen nuestras identidades.[4] También han estudiado cómo desde estas identidades percibimos el mundo que nos rodea, hacemos juicios, tomamos decisiones y actuamos. No solo el horror del presente parece haber naturalizado la violencia. También el pasado que desde este presente narramos y que se convierte eventualmente en fundamento de nuestras identidades y de nuestros posibles futuros. Y de ahí los peligros. Una violencia naturalizada puede invocar repuestas generalizadoras, normativas y moralizantes que igualen en el presente, por ejemplo, los crímenes de Estado y la protesta civil, y en consecuencia oculten, tras un aparente y generalizado pacifismo, un utillaje reaccionario. Pero una sociedad que asume que la violencia, así como el atraso o la derrota son condiciones inescapables o destinos ineludibles podría condenarse también a la inacción y, como decía Michel-Rolph Trouillot, a reducir el rango de lo pensable y de lo posible.[5]

Alteridad del pasado como resistencia

Los historiadores tenemos un papel importante, aunque no exclusivo, en la producción de estas narrativas. No estamos por fuera del presente abrumador que las sustenta y nuestras investigaciones son, en buena medida, resultado de las preguntas que nos resultan políticamente apremiantes hoy, pero también de las preguntas que, siguiendo a Trouillot, nos es concebible formular. En medio de un difícil proceso de paz y de una violencia política de nuevo en ascenso, resulta urgente reconocer las diferentes formas y experiencias de violencia.[6] A pesar de la oposición del gobierno, este reconocimiento avanza hoy en Colombia a través de organizaciones civiles y de las instituciones creadas con el Acuerdo de Paz. Investigaciones históricas recientes intentan también recuperar el significado de lo sucedido y contribuir con el necesario duelo colectivo.[7] Pero es también urgente, no solo como requisito disciplinar sino como ejercicio político, contrarrestar el peso que el presente ha impuesto sobre nuestras narrativas históricas reconociendo y desentrañando la alteridad del pasado. En este sentido, la producción historiográfica se ha diversificado y expandido también de manera dramática, incluyendo historias de resiliencia y dignidad no solo de sobrevivientes del último medio siglo de violencia sino también de nuestros pasados más remotos. No pocos historiadores han tratado de hacerse preguntas antes impensables para discernir la agencia política de los actores del pasado con sus contingencias y contradicciones, visibilizar sus esperanzas y sus expectativas, y complejizar así persistentes narrativas derrotistas y victimizantes.[8] Tal y como escribió el historiador Samuel Moyn: “nuestros ancestros estaban tratando de ser ellos mismos, no de anteceder a alguien que vendría después. El pasado no es solamente un espejo en el que nos vemos a nosotros mismos.”[9] Y no es, necesariamente, un espejo de nuestra violencia contemporánea.

El esfuerzo por reconocer y hacer visible la alteridad del pasado remoto con respecto a la violencia de hoy, puede permitirnos quizás resistir las trampas de nuestro dolor presente y, por qué no, reconstruir lentamente nuestras identidades y el rango de lo que consideramos que nos es posible como sociedad. La visibilización de actores y acciones del pasado, hasta ahora encerrados en narrativas monolíticas y totalizadoras, puede ser un paso para crear lo que Henry Giroux llamó contramemorias, es decir, memorias de resistencia con las que se haga frente al relato oficial, que “desajusten” las representaciones generalizadas de nuestro pasado, que desnaturalicen la victimización, el atraso, la derrota, o la violencia, o que las desafíen como historias únicas. Tal y como hemos aprendido de la historia decolonial, repensar la historia es fundamental para deconstruir narrativas que han ocultado o ignorado pasados que pueden ser determinantes hoy en procesos de autodeterminación y de dignidad.

Historia pública y contramemoria

De parte de los historiadores, la construcción de contramemorias requiere también de estrategias para la circulación pública y crítica de los pasados hasta hace poco impensables con los que nuevas generaciones de historiadores nos retan. En Colombia se avanza en esta tarea con ejercicios de memoria histórica, y con la divulgación de investigaciones recientes a través de proyectos de historia pública.[10] Sin embargo, se ha hecho aun poco por reconocer el carácter político del pensamiento histórico y entonces, por crear pedagogías para incentivarlo más allá de las aulas y de los departamentos de historia.[11] La existencia de una relación activa con el pasado, como han escrito, entre otros, filósofos como Hans-Georg Gadamer o historiadores como Jörn Rüsen, es antecedente necesario para motivar y orientar las acciones humanas.[12] La conciencia de la historicidad del presente tiene entonces efectos no solo en las formas de conocer, sino en las formas de actuar. El pensamiento histórico es entonces, profundamente político. Permite desnaturalizar lo que es histórico y romper así con la idea de que algo siempre ha sido de cierta manera y entonces siempre lo será. Las posibilidades de futuro, y la voluntad de actuar para lograr ese futuro, provienen de lo que el pasado nos muestra: que una guerra no es igual a otra guerra; que en los momentos de crisis ha habido no solo destrucción y muerte, sino resistencia y creatividad: que en el pasado ha habido no solo opresión o indiferencia, sino también acciones desafiantes, solidaridad, y compasión. Así la historia no solo nos enfrenta con el dolor, la devastación y la injusticia, sino también nos permite imaginar otros futuros y buscarlos. El pensamiento histórico impide entonces que vivamos en un eterno presente claustrofóbico y sin salida y, así mismo, en un presente indiferente o despolitizado.

“Pensar acerca de la historia” no es lo mismo que “pensar con la historia,” pero la manera en que nos acercamos a lo primero, contribuye en la manera en que logramos lo segundo. Pensar con la historia es urgente hoy, cuando el capitalismo avanzado y las democracias occidentales parecen obsesionadas con el presente, y cuando son innegables las amenazas políticas de la postverdad que parece ser otra forma de presentismo. Pero también es urgente para emanciparnos de la historia de permanente violencia y fracaso que, al menos en Colombia, hemos construido y narrado. Aunque parezca paradójico, reconocer la alteridad del pasado es, en este caso, una forma de abrazar el presentismo y la necesidad presente de sanarnos. Escribo desde un país que se encuentra en una coyuntura desesperanzadora. La imaginación histórica puede ayudarnos a salir del tiempo-trauma de las narrativas de permanente violencia y contribuir en la formación de una sociedad que pueda pensar un futuro por fuera de la guerra.[13] Puede ser entonces una forma de resistencia no solo frente al encarcelamiento del presente, sino frente a la muerte misma.

_____________________

Bibliografía

- François Hartog, Regímenes de historicidad: presentismo y experiencias del tiempo, México: Universidad Iberoamericana, 2007.

- Henry Giroux, Pedagogía y política de la esperanza, Buenos Aires: Amorrortu, 2003.

- John Tosh, Why History Matters, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Vínculos externos

- Historia de Par en Par Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/historiadeparenpar/ (last accessed 18 October 2021).

- Historias para lo que viene, Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/historiasparaloqueviene/ (last accessed 18 October 2021).

- ¡BASTA YA! Colombia: memorias de guerra y dignidad: https://www.centrodememoriahistorica.gov.co/micrositios/informeGeneral/ (last accessed 18 October 2021).

_____________________

[1] Armitage, David, “In Defense of Presentism,” Darrin M. McMahon ed., History and Human Flourishing Oxford, 2020; Coss, Peter, “Presentism and the ‘Myth’ of Magna Carta,” Past and Present, 234 (2017): 227–35.

[2] Francois Hartog, Regimes of Historicity: Presentism and Experiences of Time, New York, 2015.

[3] Entrevista a Jorge Orlando Melo por María Paulina Ortiz, “En Colombia existe una tradición que hizo aceptable el uso de la violencia,” El Tiempo, 5 de septiembre, 2021.

[4] Rüsen, J. “Historical consciousness: Narrative structure, moral function, and ontogenetic development.” P. Seixas ed., Theorizing historical consciousness, University of Toronto Press, 2004, 63–85; Gillis, John R., ed., Commemorations. The Politics of National Identity, PrincetonUniversity Press, 1994.

[5] Trouillot, Michel-Rolph, Silencing the Past. Power and the Production of History, Boston: Beacon Press, 1995.

[6] Entre otros ver: Roldán, Mary, Blood and Fire. La Violencia in Antioquia, Colombia, 1946-1953, Duke University Press, 2002; Ortiz, Carlos Miguel, Estado y subversión en Colombia. La Violencia en el Quindío, años 50, Bogotá: CEREC, 1985; Betancour, Darío y Marta Luz García, Matones y Cuadrilleros. Origen y evolución de la violencia en el occidente colombiano, Bogotá: TM, 1991.

[7] Ver: Bolívar, Ingrid, Discursos emocionales y experiencias de la política. Las FARC y las AUC en los procesos de Negociación del Conflicto (1998-2005), Bogotá: Uniandes, 2006; Orozco, Iván, Combatientes, rebeldes y terroristas: guerra y derecho en Colombia, Bogotá: Temis, 2006; Wills, María Emma, “Los tres nudos de la guerra en Colombia.” Comisión Histórica del Conflicto y sus Víctimas, Bogotá, 2015.

[8] Entre otros ver: Sanders, James E., The Vanguard of the Atlantic World. Creating Modernity, Nation, and Democracy in Nineteenth-Century Latin America, Durham: Duke University Press, 2014; Lasso, Marixa, Myths of Harmony: Race and Republicanism during the Age of Revolution, Colombia, 1795-1831, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2007; Garrido, M., Gutiérrez, D., y Camacho, C., Paz en la República. Colombia, siglo XIX, Bogotá: U. Externado, 2018; Robert Karl, Forgotten Peace: Reform, Violence, and the Making of Contemporary Colombia, U. California Press 2017.

[9] Moyn, Samuel. Human Rights and the Uses of History, Verso, 2014.

[10] Ver: A. Pérez y S. Vargas, “Historia Pública e investigación colaborativa: perspectivas y experiencias para la coyuntura actual colombiana,” ACHSC, Vol 46 No. 1 (2019): 297-329.

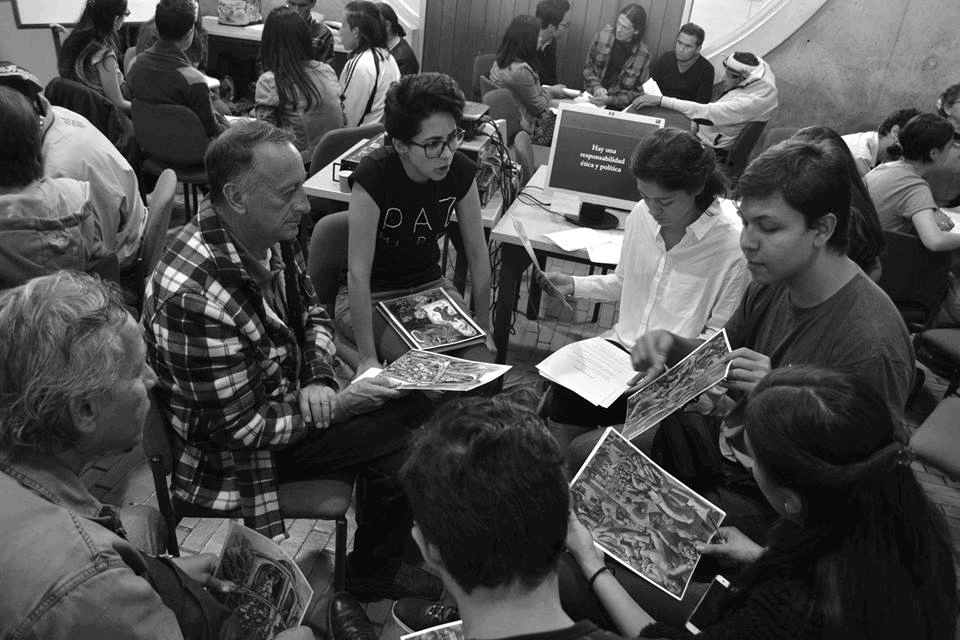

[11] En el año 2015, durante el plebiscito que refrendaría el acuerdo de paz, formamos, con un grupo de estudiantes y jóvenes historiadores, Historia entre todos, un proyecto de pedagogía para la paz desde la historia. Basados en algunas de las ideas aquí escritas hemos trabajado desde entonces en zonas urbanas y rurales en Colombia.

[12] Gadamer, Hans-Georg. El problema de la conciencia histórica, Madrid: Tecnos, 1993; Russen, Jörn. “Historical consciousness.”

[13] Dominick LaCapra, Escribir la historia, escribir el trauma, Buenos Aires, Nueva Visión, 2005.

_____________________

Créditos de imagen

Workshop Historia entre todos, Public Library, Bogotá. Courtesy of: Jimena Urbina.

Citar como

Castro, Constanza: Historizar la violencia, politizar el presente. In: Public History Weekly 9 (2021) 8, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-18867.

Responsabilidad editorial

Writing from Colombia, a country that finds itself at a hopeless juncture, the author invites us to think about how historical imagination can help us to move out of the time-trauma of the narratives of permanent violence and to contribute to shaping a society that can think of a future outside of war.

Violence as Past and Fate

One of the premises on which history as a discipline has been built is critiquing the imposition of present-day concerns, interests, and values on past actors. In recent decades, however, the historian’s relationship with the present has become more complex. So-called “presentism” has ceased being considered transgressive and has become contested instead. There is, in fact, a general consensus among historians today that a certain presentism is inescapable, for the past is not an objective reality that can be interpreted on its own terms.[1] Also, if there were no presentist motivations, what would become of history from below? What about feminist and postcolonial studies? And what about public history?

But turning the past into a mirror of the present is another matter. In the Colombian case, this is perhaps an inevitable, yet also dangerous way of dealing with the pains of a war spanning half a century-long. The narratives we often hear in the media, in films, and in everyday conversations dehistoricize the violence in Colombia by constructing colonial or republican pasts that are essentially myths of origin of an apparently inescapable violent present. According to François Hartog, this presentist-time is always trauma-time. That is, it is the time of an omnipresent present, marked by the closure of the future and by a never-ending past.[2] It is a time that prevents us from unraveling other possible pasts, and with them, imagining different possible futures.

Supported by theories of modernization, development or dependency, during the second half of the twentieth century, many historians in Latin America constructed a past that, whether due to the imposition of Spanish institutions, or the constant civil wars in the 19th century, or a dependent economy, could only precede or explain the region’s alleged backwardness. Similarly, albeit for different reasons, much of the history narrated and written about Colombia’s violent 20th century has constructed Republican and even colonial pasts that are inexplicable outside this comprehensive narrative of violence. Only a few months ago, Jorge Orlando Melo, a renowned Colombian historian, published a book on the arguments used to justify the use of political violence in Colombia. In a recent interview, he affirmed: “In the Conquest, it was licit to kill Indians. In the Colony, violence against rebels was allowed. During Independence, it was valid to replace the tyrant, and in the 19th century, to eliminate the political enemy. In the last sixty years, violence has been defended as a legitimate means to destroy an oppressive regime and, in response, to defend against the subversive response.”[3] A historical book on the justifications of violence through time is undoubtedly important, and this book’s scope, questions and sources are particularly impressive. In his introduction, the author explains also that the present violence “is not simply a prolongation of the past” as national historiography has long argued. However, in an interview reaching out to a wide audience, violence is presented as an inescapable feature of Colombia’s history. The conquest was of course violent, and this violence was not limited to present-day Colombia, but prevailed across Spanish America. The Spaniards justified violence against the Indians in the same way throughout the conquered territory. The post-independence civil wars of the nineteenth century shook most of the new republics, and the right of rebellion was invoked by those who took up arms. Throughout the same century, attempts to achieve peace were also constant and widespread throughout Latin America, although these have received much less attention than war. According to Melo, “this reality,” which has always been considered violent, “has created in Colombians, regardless of the ideological current to which they belong, the imaginary that violence is legitimate when it is used to subdue political enemies.” But is it not rather that this very characterization of our history has created this imaginary, at least to some extent?

Historians and anthropologists have found that our identities are built on what we learn from the past, on what we remember, and on the memories we pass on.[4] They have also studied how we perceive the world around us, and how we judge, decide, and act based on these identities. It is not only the present horror that seems to have naturalized violence; it is also the past that we narrate from this present, and which eventually becomes the foundation of our identities and our possible futures. It is precisely here that danger lurks. A naturalized violence can invoke normative, and moralizing responses that in the present equate state crimes and civil protest, for example. These responses can conceal a rather reactionary attitude, one lying behind an apparent and generalized pacifism. But a society that assumes that violence, backwardness, or defeat are inescapable conditions or unavoidable fates could also condemn itself to inaction. Or as the historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot put is, to allow the range of the thinkable and the possible to be reduced.[5]

The Alterity of the Past as Resistance

Historians have played an important, though not exclusive role in producing these narratives. We are not removed from the overwhelming present that sustains them. Our research results quite considerably from the questions we find politically pressing today, but also from those, which following Trouillot, we can conceivably ask. Amid a difficult peace process, and with political violence once again on the rise, it is crucial to continue recognizing the different forms and experiences of violence.[6] Despite the government’s opposition, this recognition is progressing today through civil organizations and the institutions created with the signing of the Peace Accord. Recent historical research continues to recover the meaning of what happened, and to pave the way to a much-needed collective mourning.[7] But it is also crucial — as a disciplinary requirement and as a political exercise — to counteract the weight imposed by the present on our historical narratives by acknowledging and unravelling the alterity of the past.

In this sense, historiographical production in Colombia has also diversified and expanded dramatically, including stories of resilience and dignity — not only of survivors of the last half-century of violence but also of our more remote pasts. Some historians have attempted to ask previously unthinkable questions in order to discern the political agency of past actors with their contingencies and contradictions, to make their hopes and expectations visible, and thus to challenge persistent defeatist and victimizing narratives.[8] As historian Samuel Moyn observes: “Our ancestors were trying to be themselves rather than to anticipate somebody else. The past is not simply a mirror for our own self-regard.”[9] Neither is it necessarily a mirror of our contemporary violence.

The effort to acknowledge and render visible the alterity of the past in relation to contemporary violence can perhaps allow us to resist the traps of our present and — why not — to slowly rebuild our identities and the range of what we consider possible for us as a society. Visibilizing past actors and actions past, until now enclosed in monolithic and totalizing narratives, can constitute a step towards creating what Henry Giroux has called counter-memories; that is, memories of resistance that challenge the official narrative, that “unsettle” the generalized representations of our past, that denaturalize victimization, backwardness, defeat, or violence, or that challenge them as single stories. As we have learned from decolonial history, rethinking history is fundamental to deconstructing narratives that have hidden or ignored pasts, which can be decisive in contemporary processes of self-determination and dignity.

Public History and Counter-Memory

At least for historians, constructing counter-memories also requires strategies for the public and critical circulation of the hitherto unthinkable pasts with which new generations of historians are challenging us. In Colombia, we have pursued this task through historical memory exercises, as well as by disseminating recent and challenging research through public history projects.[10] However, little has been done to recognize the political character of historical thinking and thus to create pedagogies that encourage such thinking beyond the classroom — and beyond history departments.[11] The existence of an active relationship with the past, as articulated by philosophers such as Hans-Georg Gadamer or historians such as Jörn Rüsen, is a necessary prerequisite to motivating and guiding human actions.[12] This consciousness of the historicity of the present affects not only our modes of knowing, but also our modes of acting. Historical thinking is thus profoundly political. It denaturalizes what is historical, dispelling the idea that things have always been and will remain as they are. Possible futures, and the will to act to achieve them, come from what the past shows us: that one war is not equal to another war; that in moments of crisis there has been not only destruction and death, but resistance and creativity; that we can find in the past, not only oppression or indifference, but also defiant actions, solidarity, and compassion. Thus, history not only confronts us with pain, devastation and injustice, but also allows us to imagine other futures and look for them. Thus, historical thinking keeps us from living in an eternal and claustrophobic, yet at the same time indifferent and depoliticized present.

“Thinking about history” is not the same as “thinking with history.” But how we approach the former contributes to how we achieve the latter. Thinking with history is a pressing concern today, when advanced capitalism and Western democracies seem obsessed with the present, and when the political threats of post-truth — which appears to be another form of presentism — are undeniable. Thinking with history is also urgent, in order to emancipate ourselves from the history of permanent violence and failure that we have constructed and narrated. Paradoxical though it may seem, acknowledging the alterity of the past enables us to embrace presentism, as well as the present need to heal ourselves. I write from a country that finds itself at a hopeless juncture. Historical imagination could help us to move out of the time-trauma of the narratives of permanent violence and to contribute to shaping a society that can think of a future outside of war.[13] Such imagination can therefore serve as a form of resistance — not only to the imprisonment of the present, but to death itself.

_____________________

Further Reading

- François Hartog, Regímenes de historicidad: presentismo y experiencias del tiempo, México: Universidad Iberoamericana, 2007.

- Henry Giroux, Pedagogía y política de la esperanza, Buenos Aires: Amorrortu, 2003.

- John Tosh, Why History Matters, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Web resources

- Historia de Par en Par Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/historiadeparenpar/ (last accessed 18 October 2021).

- Historias para lo que viene, Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/historiasparaloqueviene/ (last accessed 18 October 2021).

- ¡BASTA YA! Colombia: memorias de guerra y dignidad: https://www.centrodememoriahistorica.gov.co/micrositios/informeGeneral/ (last accessed 18 October 2021).

_____________________

[1] Armitage, David, “In Defense of Presentism,” Darrin M. McMahon ed., History and Human Flourishing Oxford, 2020; Coss, Peter, “Presentism and the ‘Myth’ of Magna Carta,” Past and Present, 234 (2017): 227–35.

[2] Francois Hartog, Regimes of Historicity: Presentism and Experiences of Time, New York, 2015.

[3] Interview with Jorge Orlando Melo by María Paulina Ortiz, “En Colombia existe una tradición que hizo aceptable el uso de la violencia,” El Tiempo, 5 de septiembre, 2021.

[4] Rüsen, J. “Historical consciousness: Narrative structure, moral function, and ontogenetic development.” P. Seixas ed., Theorizing historical consciousness, University of Toronto Press, 2004, 63–85; Gillis, John R., ed., Commemorations. The Politics of National Identity, Princeton University Press, 1994.

[5] Trouillot, Michel-Rolph, Silencing the Past. Power and the Production of History, Boston: Beacon Press, 1995.

[6] See among many others: Roldán, Mary, Blood and Fire. La Violencia in Antioquia, Colombia, 1946-1953, Duke University Press, 2002; Ortiz, Carlos Miguel, Estado y subversión en Colombia. La Violencia en el Quindío, años 50, Bogotá: CEREC, 1985; Betancour, Darío and Marta Luz García, Matones y Cuadrilleros. Origen y evolución de la violencia en el occidente colombiano, Bogotá: TM, 1991.

[7] See, among others: Bolívar, Ingrid, Discursos emocionales y experiencias de la política. Las FARC y las AUC en los procesos de Negociación del Conflicto (1998-2005), Bogotá: Uniandes, 2006; Orozco, Iván, Combatientes, rebeldes y terroristas : guerra y derecho en Colombia, Bogotá: Temis, 2006; Wills, Maria Emma, “Los tres nudos de la guerra en Colombia.” Comisión Histórica del Conflicto y sus Víctimas, Bogotá, 2015.

[8] See among others: Sanders, James E., The Vanguard of the Atlantic World. Creating Modernity, Nation, and Democracy in Nineteenth-Century Latin America, Durham: Duke University Press, 2014; Lasso, Marixa, Myths of Harmony: Race and Republicanism during the Age of Revolution, Colombia, 1795–1831, 2007; Garrido, M., Gutiérrez, D., y Camacho, C., Paz en la República. Colombia, siglo XIX, Bogotá: U. Externado, 2018; Robert Karl, Forgotten Peace: Reform, Violence, and the Making of Contemporary Colombia, U. California Press 2017.

[9] Moyn, Samuel. Human Rights and the Uses of History, Verso, 2014.

[10] See: A. Pérez and S. Vargas, “Historia Pública e investigación colaborativa: perspectivas y experiencias para la coyuntura actual colombiana,” ACHSC, Vol 46 No. 1 (2019): 297-329.

[11] During the 2015 plebiscite, we launched the history-based peace education project Historia entre todos together with a group of students and young historians. The project aimed to endorse the peace agreement. Based on some of the ideas presented here, we have since been working in urban and rural areas in Colombia.

[12] Gadamer, Hans-Georg. El problema de la conciencia histórica, Madrid: Tecnos, 1993; Rüsen, Jörn. “Historical consciousness.”

[13] Dominick LaCapra, Escribir la historia, escribir el trauma, Buenos Aires, Nueva Visión, 2005.

_____________________

Image Credits

Workshop Historia entre todos, Public Library, Bogotá. Courtesy of: Jimena Urbina.

Recommended Citation

Castro, Constanza: Historicizing Violence, Politicizing the Present. In: Public History Weekly 9 (2021) 8, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-18867.

Editorial Responsibility

Copyright © 2021 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 9 (2021) 8

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-18867

Tags: Colombia, Counter Memory (Gegenerinnerung), South America (Südamerika), Traumata

To all readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 22 languages. Just copy and paste.

OPEN PEER REVIEW

We are responsible for each separate choice

“Historicizing Violence” makes a critical contribution to an important debate in international public history, steeped in the specifics of historical identity in Colombia, but applicable to contexts all over the world. The author explores how a dominant popular narrative that Colombia has always been a violent country has been cultivated in part by historians, with dangerous consequences, contributing to a naturalization of violence as a solution to conflict. The author then calls on historians working in and out of the academy to uplift the “alterity of the past” and open the “range of what we consider possible in our society.”

Many historians, including me and Catalina Muñoz in her brilliant editorial here, have called out the persistent disjunctures between history and transitional justice, as well as the potential for collaboration.[1] Much of this criticism focuses on what extent of historical time is relevant for understanding and moving through present conflict — in other words, how far back to go. Transitional justice focuses on recent violence, and direct, visible accountability for it. Historians commonly argue that recent violence cannot be explained, and addressed, without exploring its deeper systemic roots. Where legal testimony focuses solely on people’s memories of a violent event, oral history invites people to share their experiences before, after, and outside a conflict, exposing violence’s variegated roots, and the complex humanity of its actors. Here the long view brings necessary nuance.

“Historicizing Violence” shatters this dichotomy, by noting how in the Colombian case, historians have in fact used the longue duree to oversimplify, by tracing an uninterrupted line from the violence of conquest to the recent conflict. Stressing historical consistency has had the effect of producing a narrative of Colombia as “a violent country by nature”, making the situation seem impossible to change. This kind of history thwarts the transformation sought by transitional justice and peace building efforts, limiting a society’s ability to imagine another way.

The article inspired me to think in new ways about the possibilities and dangers of continuity narratives in public history. I’ve been reflecting on how our thinking about relating past and present has evolved between 1999, when I organized the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience[2] in a very different time for memory and transitional justice, and now, when reparations campaigns for historical violence are erupting across the US. The group that Ruth Abram and I first brought together — including Memoria Abierta in Argentina, the Gulag Museum in Russia, and the Lower East Side Tenement Museum in the United States — declared they “hold in common the belief that it is the obligation of historic sites to draw explicit connections between the past and the present and stimulate dialogue on pressing social issues” in order to “promote democratic and humanitarian values.” But they had very different ideas about how.

Founding sites shared two different approaches to connecting past and present. The first involved looking at two different moments in time, where conditions were similar, but the society responded to them in a different way. For instance, the Workhouse in England showed visitors how British society treated people in poverty in 1824, and invited them to compare this to the present day. This strategy focused on comparisons, not continuities; the past was offered as a resource for solutions to present-day problems, like something between a thesaurus and an encyclopedia. This offered alterity (as this article’s author puts it) without accountability: the past presented another option, but didn’t directly shape the present, so wasn’t responsible for it.

The second approach stressed this historical responsibility, drawing an uninterrupted line between past and present to show exactly who did what and who should pay. For instance, the District Six Museum in Cape Town mobilized former residents of the neighborhood, whose homes had been destroyed by the apartheid government, to remember their community and make specific claims to get their land back. The push for accountability here didn’t need alterity; the focus on identifying what was lost and establishing that it needed to be restored didn’t leave much time for pondering how it could have gone another way.

Over the last few years, campaigns for Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation,[3] as well as for material reparations,[4] have erupted across the United States. These campaigns are based on an argument of historical continuity: that the United States was founded on white supremacy, and built on structural racism. But these campaigns are wholly dedicated to accountability and transformation, so they, like the Colombian efforts promoted by this article’s author, resist creating “an eternal and claustrophobic — but, at the same time, indifferent and politicized — present”. The historical thinking that seems most promising to me traces the consistency of white supremacy throughout American history, but stresses that structures of racism have been built anew in each generation. In other words, redlining, mass incarceration, and police murder of Black Americans are not inevitable outgrowths of the “original sin” of slavery, but distinct systems white Americans actively chose to reproduce and recommit ourselves to time and again. This means that we are responsible for each separate choice — but also that in each historical moment, people could have made a different one. This historical thinking combines accountability and alterity, going back to the roots while exposing and encouraging possibilities for different branches to grow. I am grateful to this article on Colombia for the insights it offers for my own country.

—

[1] Liz Ševčenko, “Sites of Conscience: Reimagining Reparations,” Change Over Time 1, no. 1 (Spring 2011): 6-33; Sebastian Brett,Louis Bickford, Liz Ševčenko, Marcela Rios, “Memorialization and Democracy: State Policy and Civic Action,” https://www.ictj.org/publication/memorialization-and-democracy-state-policy-and-civic-action; John Torpey, Politics and the Past : on Repairing Historical Injustices. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003; Fanie du Toit, “En(countering) Silence – Some Thoughts on Historical Justice after Memoricide,” International Public History. 2020; 3(2): https://doi.org/10.1515/iph-2020-2005.

[2] International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, https://www.sitesofconscience.org/en/home/ (last accessed 22 Oct 2021).

[3] H.Con.Res.100 – Urging the establishment of a United States Commission on Truth, Racial Healing, and Transformation, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-concurrent-resolution/100/text (last accessed 22 Oct 2021).

[4] ´Reparations for Black Residents are becoming a local issue als well as a national one´. In The New York Times 25 Sep 2021.