Abstract:

Threatened by the twin catastrophes of climate breakdown and species extinction and in the grip of a global pandemic, humanity’s purchase on a positive future is looking increasingly tenuous. In addition, global trends towards right-wing populism and proto- fascism, allied to growing distrust of mainstream media and the proliferation of systems of disinformation, weaken efforts to tackle the mounting emergencies. In this period of multiple and intersecting crises, how does history education respond? A starting point is to consider what are the capacities needed by this and future generations of young people to meet these existential threats and adapt to changing contexts. These could include supporting young people to become critical, engaged and active citizens, prepared to question received truths, interrogate their own positionality and look beyond self-interest, and with the capacity to imagine the world otherwise. Is history education up to the task?

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17409

Languages: English

Threatened by the twin catastrophes of climate breakdown and species extinction and in the grip of a global pandemic, humanity’s purchase on a positive future is looking increasingly tenuous. In addition, global trends towards right-wing populism and proto-fascism, allied to growing distrust of mainstream media and the proliferation of systems of disinformation, weaken efforts to tackle the mounting emergencies. In this period of multiple and intersecting crises, how does history education respond?

Supporting Young People

A starting point is to consider what are the capacities needed by this and future generations of young people to meet these existential threats and adapt to changing contexts. These could include supporting young people to become critical, engaged and active citizens, prepared to question received truths, interrogate their own positionality and look beyond self-interest, and with the capacity to imagine the world otherwise. Is history education up to the task?

Currently, we are facing a perfect storm in terms of existential threats to the continuation of life on this planet, at least in a form that is consistent with what we consider a good life. Irreversible climate breakdown is becoming more likely with each failure to marshal the global political will needed to reduce carbon emissions and to challenge dominant economic models of unsustainable growth. At the same time, and similarly influenced by human activity, we are in the middle of a crisis of biodiversity where upwards of one million species are threatened with extinction in the coming decade.[1] The destruction of habitats and the changing climate have created more permeable boundaries between human communities and other species, leading to increased likelihood of cross-species contagion and pandemics, such as we are currently witnessing in relation to Covid-19.[2]

Allied to these very real physical threats to our continued existence, the social and political infrastructure that offer us some possibility of climate and biodiversity action are themselves in jeopardy, with international bodies and democratic institutions of state and media increasingly vulnerable to attack from right wing extremists, conspiracy theorists, anti-democratic forces and disinformation propagandists. The resulting miasma of suspicion and distrust surrounding scientific facts and public institutions that has infected huge swathes of the global population makes progress on these complex issues more difficult to achieve and threatens our capacity to respond appropriately to the challenges facing us.

Digging Deeper

Citizenship education is amongst the most frequently cited extrinsic aims of school history. Traditionally focused on promoting identification with the nation state and characterised by direct teaching of national narratives, it left little room for individual or collective voices that challenged received truths or offered an alternative vision of the good life.[3] More recently, and informed by a Deweyan conceptualisation of education for democratic citizenship, history’s potential to develop the kinds of capacities and habits of mind that support democratic engagement has seen renewed interest, particularly in its capacity to promote reflective, enquiry-based, multi-perspectival interrogations of the past in ways that connect with present issues and conflicts.[4]

In addition, the role of evidence in the construction of historical knowledge and the validation of claims through historical argument provide obvious starting points from which to challenge the current malaise of disinformation and the propensity of people to fall hostage to confirmation-bias, addressing only the evidence that tells their preferred story. Indeed, you could argue that the potential of history to contribute to education for democratic citizenship has been well-mined and that pushing the relationship further risks undermining the intrinsic value of history as a discipline, exposing it to charges of presentism or even propaganda. I suggest that it has not gone far enough, however, and that the exigencies of the current crises require us to dig deeper. This is particularly the case when we consider the differential impact of these multiple crises across time and space; issues of justice, whether local, global or intergenerational require a more robust response.

What is my Community?

The emergence of critical enquiry approaches which draw on critical theory and critical pedagogy open the possibility of a more transformative orientation in history teaching, which takes account of global and intergenerational justice, addressing the kinds of capacities needed to engage with current and future contexts.[5] These could include, for example, the capacity to understand that privilege, local and global, is historically constructed and continues to manifest itself in current crises. Unless we have the capacity to recognise and move beyond self-interest and/or group interest, there is little hope of effective action on climate or any other global issue. Moving beyond self-interest also requires us to think critically about identity and community and to recognise that we simultaneously belong to multiple collectives, including the human collective, depending on the lens applied while, at the same time, challenging the idea that categories such as “people in the past” all shared the same experiences by recognising cleavages of class, gender, race and power.

Those communities should also include the community of all living things that inhabit our planet; the idea that the wellbeing of human communities and the natural world are inextricably linked has never been more clear than during the current pandemic. Understanding the historical relationship between human communities and the natural environment is critical to understanding how we got here in the first place. Western concepts of human mastery over nature or instrumentalist conceptions of the natural world need to be deconstructed and challenged through looking critically at their development, how they manifested themselves through changing agricultural and industrial practices and the long term, as well as more immediate, consequences of those changes. For example, the benefits of cheaper food for western industrialised countries in the short term needs to be set against the cost that accrued to other global communities and the environmental destruction caused. Exploring alternative conceptions of nature found in diverse human communities and indigenous cultures over time, in ways that neither exoticise nor fossilise them, enable children to construct new visions of that relationship.

Whose Actions Count?

For adults and children alike, growing awareness of the threats associated with the climate crisis can evoke feelings of helplessness, fatalism and despair; continued reporting of the shrinking timescale for intervention can promote a sense of its inevitability and belief that there is nothing we, as individuals, can do to change things. Believing that our actions count for nothing allows us to continue to act as we have always done, and puts the responsibility for doing onto the shoulders of others. Understanding the relationship between historical change and human decision-making helps counter feelings of powerlessness, inevitability and fatalism in the face of seemingly intractable problems.

Historical agency is not a morally neutral concept, however, and historians of the future will deal very differently with the collective action of the Black Lives Matter or Fridays for Futures movements and the events that unfolded in Washington on January 6th, 2021. If a focus on agency is to have transformative intent, it needs to ask hard questions relating to perspective, power and interest, and not avoid issues of accountability and culpability in relation to historic injustices. Plotting the historical timeline for the climate crisis, for example, will encompass asking critical questions relating to the links between industrialisation and Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade (such as those raised by the campaign to remove public statues commemorating individuals with links to slavery). Taking a critical perspective on change and historical agency allows children to ask questions about whose actions have been privileged in historical narratives and whose are not represented. It recognises also that historical change is not experienced in similar ways by all groups. Asking questions such as ‘Who benefitted from this change? Who was disadvantaged? How is this connected to the present’, for example, is essential to the deconstruction of dominant narratives relating to progress and growth and to addressing issues of local and global justice.[6] In order to do this effectively, we need to enable children to ask different questions of history, moving out in time and space to see the bigger picture, taking a closer look to understand the links between power and interest and to hold historical actors, whether collective or individual, to account in questions of justice (including children’s own communities), and, drawing on the idea of counterfactual history, consider whether different actions might have prompted different outcomes.

Back to the Future

Taking a critical perspective on change and challenging narratives of progress also requires that we ask questions about the negative consequences of innovations such as the combustion engine, or flight, that are generally taught as human triumphs. Extending our time scale is important. What we may perceive to represent positive change or to be in our interest in the short term, may lead to disastrous consequences in the longer term, some of which were, or could have been predicted. While recognising the value of science, scientific enquiry and technological advances to human life, an uncritical cataloguing of technological innovation as a narrative of heroic genius and individual triumph conflates a number of ideas that are problematic from a sustainability perspective, for example, that ‘new’ technologies are better and more advanced, that older technologies are disposable, old-fashioned and no longer useful. Asking more critical questions about the need for new technologies, their impact over time and the wider consequences of their development for environmental sustainability and climate justice can provide a platform for the interrogation of cultures of consumerism, wealth accumulation and technological imperialism, all of which play a role in the current crises.

Envisioning Futures

If, as Rüsen argues, the purpose of history is to enable us to orient ourselves in time, ask questions of the past that concern our lives in the present and predict a future, the current confluence of crises makes it imperative that we think seriously about what those futures might be.[7] Facing this uncertainty, children will have to be flexible, adaptive and creative; they need to know that the future is still unwritten and that the present is capable of supporting a number of outcomes; that their actions, individually and collectively, can have an impact on those futures; that their interests are dependent on the interests of all other peoples, species and natural environments; that there are many ways of looking at the world which give us alternative visions of future relationships and that, ultimately, what happens will be in large part subject to human decision-making.

_____________________

Further Reading

- Andreotti, Vanessa. ‘Soft versus critical global citizenship education’. Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, 3, (2006): 40-51.

- Barton, Keith. ‘Agency, choice and historical action: How history teaching can help students think about democratic decision making’. Citizenship Teaching & Learning 7, no. 2 (2012): 131-42.

- Waldron, Fionnuala, Caitríona Ní Cassaithe, Maria Barry, and Peter Whelan. Critical Historical Enquiry for a Socially Just and Sustainable World. Edited by Anne Marie Kavanagh, Fionnuala Waldron, and Benjamin Mallon. Teaching for Social Justice and Sustainable Development Across the Primary Curriculum. London: Routledge, 2021. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003003021-2.

Web Resources

- Ní Cassaithe, Caitríona. ‘Bringing the ethical back into enquiry’. PastFwd. 17 July 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9zsCE-MS8WM (last accessed 21 February 2021).

_____________________

[1] Jeff Tollefson, “Humans Are Driving One Million Species to Extinction,” Nature 569, no. 7755 (May 6, 2019): 171–171, https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-01448-4.

[2] Ferris Jabr, “How Humanity Unleashed a Flood of New Diseases,” The New York Times, June 17, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/17/magazine/animal-disease-covid.html (last accessed 21 February 2021).

[3] Alan McCully and Fionnuala Waldron, “A Question of Identity? Purpose, Policy and Practice in the Teaching of History in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland,” International Journal of History Learning, Teaching and Research 11, no. 2 (2013): 145–58.

[4] Keith C. Barton and Linda S. Levstik, Teaching History for the Common Good (Mahwah NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates., 2004).

[5] Fionnuala Waldron et al., “Critical Historical Enquiry for a Socially Just and Sustainable World,” in Teaching for Social Justice and Sustainable Development Across the Primary Curriculum, ed. Anne Marie Kavanagh, Fionnuala Waldron, and Benjamin Mallon (London: Routledge, 2021), 21–36, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003003021-2.

[6] Fionnuala Waldron et al., “Critical Historical Enquiry for a Socially Just and Sustainable World,” in Teaching for Social Justice and Sustainable Development Across the Primary Curriculum, ed. Anne Marie Kavanagh, Fionnuala Waldron, and Benjamin Mallon (London: Routledge, 2021), 21–36, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003003021-2.

[7] Jörn Rüsen, “Historical Consciousness: Narrative Structure, Moral Function, and Ontogenetic Development,” in Theorizing Historical Consciousness, ed. P. Seixas (Toronto, Buffalo and London: University of Toronto Press, 2004), 63–85.

_____________________

Image Credits

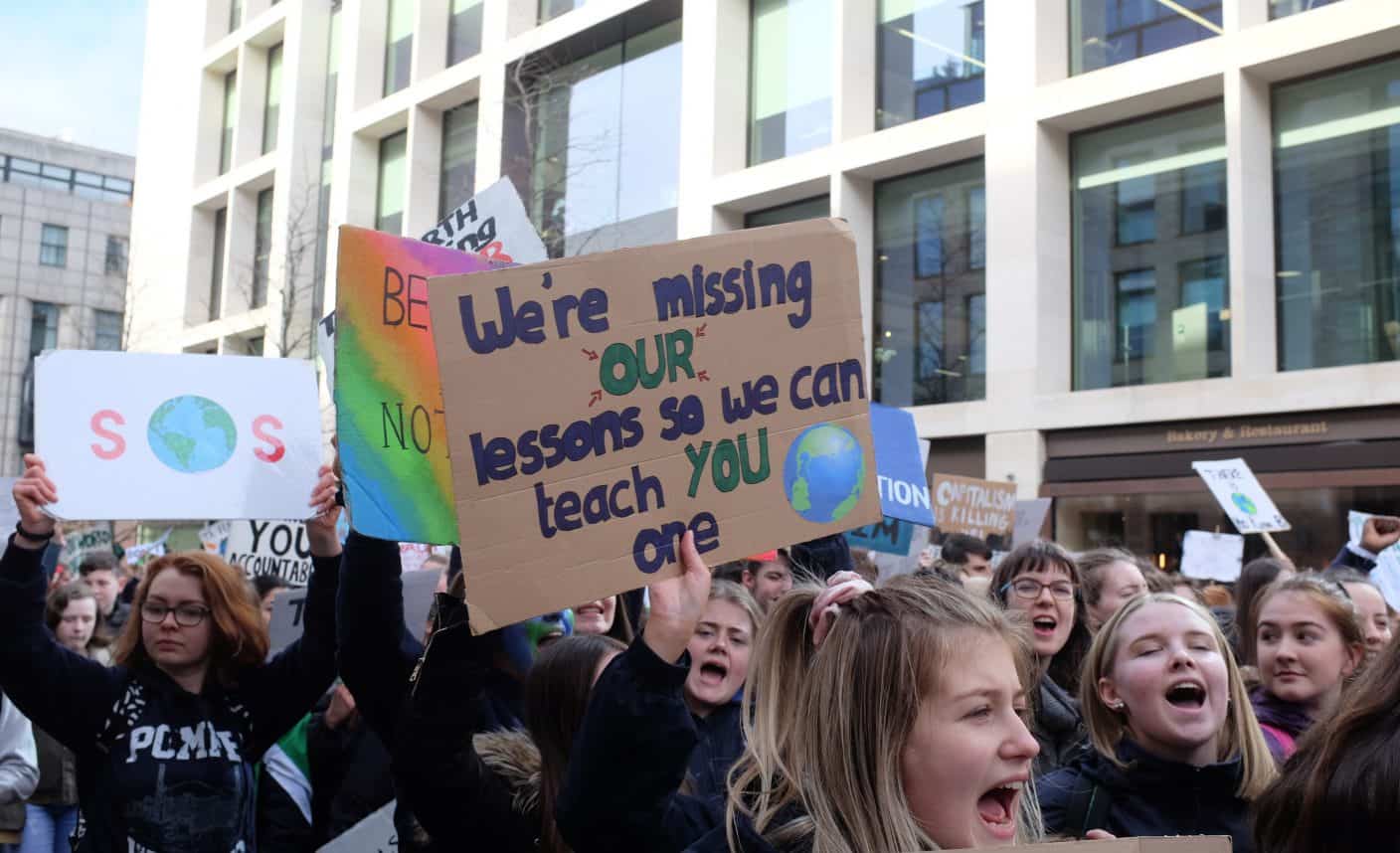

“School Strike for Climate (Dublin, Ireland)” by 350.org is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Recommended Citation

Waldron, Fionnuala: Interrogating History to Imagine a Different Future. In: Public History Weekly 9 (2021) 1, DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17409.

Editorial Responsibility

Copyright (c) 2020 by De Gruyter Oldenbourg and the author, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author and usage right holders. For permission please contact the editor-in-chief (see here). All articles are reliably referenced via a DOI, which includes all comments that are considered an integral part of the publication.

The assessments in this article reflect only the perspective of the author. PHW considers itself as a pluralistic debate journal, contributions to discussions are very welcome. Please note our commentary guidelines (https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/contribute/).

Categories: 9 (2021) 1

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1515/phw-2021-17409

Tags: Anthropocene, Civics Education (Politische Bildung), Climate Change (Klimawandel), Crises (Krisen)

To all our non-English speaking readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 11 languages. Just copy and paste.

OPEN PEER REVIEW

The Role of Bildung in Teaching for the Anthropocene

The article focuses on the role history education can have in enabling students to handle the societal challenges of the Anthropocene. The reasoning is convincing and makes the implicit connection to the idea of Bildung which puts forward that history education must prepare the students to successfully deal with their own and others’ life situations both today and in the future. That the subject of history should contribute to the development of students’ action competence,[1] could be perceived as one of the main messages of the article. The question is how to achieve this? So, perhaps not so much in polemics with the author, I want to address the issue of content when teaching about topics like the Anthropocene.

It may be perceived as somewhat presentistic, but it is difficult to get past the fact that Western societies’ exploitation of natural resources over the last 200 years represents something new in history. We have entered the age of humans, the Anthropocene.[2] As a concept, it is by no means undisputed.[3] After all, it is the Western society (broadly defined), and certain groups within it, who have been the driving force in the development of the socio-ecological systems behind today’s global environmental crisis.[4]

The author of the article makes it clear just how important it is that Anthropocene is addressed in history education. I cannot agree more on that matter. I also agree that it is necessary to pay attention to agency and the possibility of change. The article raises the issue of developing a critical perspective, which is linked to the development of historical thinking. For students to conquer a critical approach is an essential and necessary element in history education; however, for such critical thinking to become operative, it needs to be connected to a relevant historical frame of reference. Only then might the students build a robust platform for action.

The concept of Anthropocene centres on the relationship between society and nature, between humans and the ecosystem. This is hardly a particularly prominent perspective in the narrative that permeates today’s, or for that matter, yesterday’s history education, at least not in Sweden. New processes, events and actors have yet to be included in the narrative; and above all, the perspective has to be adjusted. The historical frame of reference ought to be linked to specialized knowledge in order to function as a platform for action. In that sense, the didactical what-question is difficult to ignore when the Anthropocene is addressed. The development of a critical approach emphasizing second-order concepts might become sort of a dry-run if the importance of developing a revisioned historical frame of reference is not noticed. So, if the concept of Anthropocene should have an impact on education, a reassessment of the content and structure of the historical narrative is required.

A strong argument is made in the article that history education cannot remain distantly value-neutral. I agree that the history subject has a different mission than the discipline history; the value dimension is an essential aspect of history education. The challenge is how this normativity should be expressed in teaching. How focused should the teaching be on nurturing the “right” values and attitudes? Here I may have a slightly different opinion than the one that is articulated in the article. It may seem naive, but I put my faith in the content to balance openness and closeness in teaching history. Östman (1995), a researcher of education for sustainable development (ESD), talks about the inherent normativity of the content.[5] Maybe it is possible to be guided by that idea when addressing the dimensions of value and normativity in the Anthropocene? The point then is that the selected content does give normative direction. But to counter-balance this normativity, could the teaching be organized so that the students’ independent reasoning and reflection about the content are encouraged? This approach can be related to the notion that Bildung has a role in history education, and that Bildung grows from below, based on specialized knowledge in connection to the everyday experiences of the students.

If the goal is to inspire students to develop a deeper eco-sociological understanding of history, we who are history teachers, and who try to contribute to the development of history education, have a great task ahead of us.

_____________

[1] Maria Hedefalk, Jonas Almqvist, and Malena Lidar, ‘Teaching for Action Competence’, SAGE Open 4, no. 3 (1 July 2014): 2158244014543785, https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014543785.

[2] Paul J. Crutzen, ‘Geology of Mankind’, Nature 415, no. 23 (2002), https://doi.org/10.1038/415023a.

[3] Andreas Malm and Alf Hornborg, ‘The Geology of Mankind? A Critique of the Anthropocene Narrative’, The Anthropocene Review 1, no. 1 (1 April 2014): 62–69, https://doi.org/10.1177/2053019613516291.

[4] Corey Ross, Ecology and Power in the Age of Empire: Europe and the Transformation of the Tropical World, Illustrated edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).

[5] Leif Östman, ‘Socialisation Och Mening: No-Utbildning Som Politiskt Och Miljömoraliskt Problem – Socialization and Meaning: Science Education as a Political and Environmental-Ethical Problem’ (PhD Thesis, Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, 1995).

To all our non-English speaking readers we recommend the automatic DeepL-Translator for 11 languages. Just copy and paste.

A very interesting article that highlights the important role history education has to play in helping to support young people develop as critical, engaged and active citizens capable of counteracting the potentially imminent catastrophes of climate breakdown and species extinction. I agree with Fionnuala when she highlights the need for teachers to implement historical enquiries that do not shy away from encouraging children to critically examine and ask task hard questions related to themes such as power, perspectives and interest.

Through such an approach, history education can have a transformative impact on the lives of young people and help young people to recognise that through both their individual and collective actions that they possess the capabilities to shape a brighter and better future.